Bone Lesions

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.1 – Bone Lesions

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.1 – Bone Lesions

5.1

Bone Lesions

Felasfa M. Wodajo

Osteoma

Osteoma of bone is a densely mineralized endosteal

lesion almost always seen in the head. The most common locations are in

the ethmoid and frontal sinuses. The lesions are uniformly benign and

usually discovered incidentally. In unusual cases, very large osteomas

of the paranasal sinuses can cause obstruction of the nasal air ducts

or other cranial symptoms. The radiographic hallmark is dense,

ivory-like mineralization with smooth margins. Unless there are

obstructive symptoms, observation is appropriate.

lesion almost always seen in the head. The most common locations are in

the ethmoid and frontal sinuses. The lesions are uniformly benign and

usually discovered incidentally. In unusual cases, very large osteomas

of the paranasal sinuses can cause obstruction of the nasal air ducts

or other cranial symptoms. The radiographic hallmark is dense,

ivory-like mineralization with smooth margins. Unless there are

obstructive symptoms, observation is appropriate.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

-

Unknown

-

Component of Gardner’s syndrome

Epidemiology

-

Estimated prevalence: 0.4%

-

Male:female ratio: 2:1

-

Location: ethmoid and frontal sinuses of the cranium most common

Pathophysiology

-

Osteomas are benign, indolent lesions.

-

Capacity for slow growth but no malignant potential

Diagnosis (See Algorithm 5.1-1)

Clinical Features

-

Typically incidental findings on dental or other cranial radiography

-

Occasionally, very large osteomas cause

sinus obstruction, loss of smell, or even in rare cases invasion into

intracranial structures.

Radiographic Features

-

Plain radiographs and computed tomography

(CT): smooth-contoured, densely mineralized lesion, within the

medullary bone with no cortical invasion

|

|

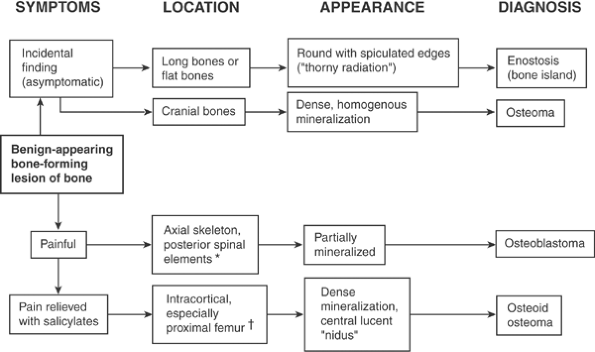

Algorithm 5.1-1.

Diagnosis of benign-appearing bone-forming lesions of bone. *Most common;may also occur in long bones, but rarely. †Most common;may also occur in posterior spinal elements and flat bone. |

Histologic Features

-

Mature lamellar bone with decreased marrow component

-

Sometimes haversian canals are seen within areas resembling cortical, compact bone.

Differential Diagnosis

Cemento-ossifying Fibroma (Ossifying Fibroma of Craniofacial Bones)

-

This is also another ossifying lesion of the cranium, but more often found in the mandible than the maxilla and cranial bones.

-

It must be distinguished from osteoma as it may have a more aggressive course and more often requires excision.

-

It appears as a well-circumscribed ossifying matrix, occasionally with expansile remodeling.

-

In contrast to dense ossification of osteoma, the periphery of these lesions is not always completely mineralized.

-

The histological appearance is also

different, showing a mix of fibrous and fibromyxoid stroma in addition

to combination of woven and lamellar bone and sometimes cementum.

Osteoid Osteoma

-

These have been described in the head and

neck and also appear as small, densely mineralized lesions but with the

important difference of a central radiolucent nidus and often nocturnal

pain relieved by salicylates, in contrast to incidental, asymptomatic

osteoma.

P.119

Chronic Sclerosing Osteomyelitis

-

Low-grade bone infections, presumably of

oral origin, occur in the maxilla and mandible and appear as sclerotic

lesions but are usually discovered due to symptoms.

Parosteal Osteosarcoma

-

A rare juxta-cortical variant of osteoma, parosteal osteoma, is sometimes confused with parosteal osteosarcoma.

-

The distinguishing feature of parosteal

osteoma is the presence of dense, homogenous mineralization, whereas

the mineralization in parosteal osteosarcoma may be incomplete and

heterogeneous.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

-

Surgical intervention is rare as the vast majority of osteomas are asymptomatic, incidental findings.

-

Excision has been occasionally reported for rare lesions with obstructive symptoms of the sinuses.

Results and Outcome (Prognosis)

-

Observed lesions may progress very slowly.

Enostosis

Enostosis or “bone island” is a small, asymptomatic,

densely mineralized lesion found within the cancellous bone. It is

typically an incidental finding; the important diagnostic challenge

often is ruling out the possibility of the lesion representing a small

bone metastasis. The characteristic radiating thick trabeculae seen on

imaging studies and absence of uptake on bone scan are distinguishing

features.

densely mineralized lesion found within the cancellous bone. It is

typically an incidental finding; the important diagnostic challenge

often is ruling out the possibility of the lesion representing a small

bone metastasis. The characteristic radiating thick trabeculae seen on

imaging studies and absence of uptake on bone scan are distinguishing

features.

Pathogenesis

-

Etiology is unknown.

Epidemiology

-

Most often found in adults undergoing

testing for other reasons, although presumably develops at a younger

age during skeletal maturation -

No gender predilection or inheritance pattern

-

Distribution

-

Found within cancellous bone

-

Preference for pelvis, femur, and other long bones

-

Relatively rare in the spine

-

Pathophysiology

-

Disorder of endochondral ossification

-

An error in resorption of the secondary

spongiosum during bone formation leads to an island of heavily

calcified matrix left within the spongy, cancellous bone.

-

-

Enostoses do not change in size over time and have no malignant potential.

Diagnosis (See Algorithm 5.1-1)

Clinical Features

-

Asymptomatic, incidental findings, usually discovered during evaluation for other reasons

Radiologic Features

Radiographs

-

Round or ovoid, homogeneously dense, sclerotic focus in cancellous bone

-

Distinctive finding is the presence of radiating bony streaks (“thorny radiation”) emanating from the sclerotic center.

-

Almost always small, ranging from 1 mm to 2 cm

-

“Giant” bone islands, measuring up to 6 cm, have been reported, but large lesions should raise suspicion for other diagnoses.

Computed Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging

-

Distinctive “brush borders” are more clearly seen on CT and are diagnostic.

-

Appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination should emulate cortical bone.

Bone Scan

-

Most important radiographic feature of

enostosis is the usual absence of uptake on bone scan, which—when

present—differentiates it from metastatic disease. -

Occasional scintigraphically active

enostoses have been described, suggesting caution in using bone scan as

the only modality for diagnosis, but bone scan remains very important

in diagnosis.

Histologic Features

-

Features include mature lamellar pattern with haversian canals within a focus of compact (cortical) bone.

-

Thickened, radiating trabeculae merge with the surrounding trabeculae in the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 5.1-1).

Differential Diagnosis

Metastasis

-

Differentiating enostosis from bone metastases is the most important diagnostic challenge.

-

Small blastic lesions can be seen in breast cancer and prostate cancer metastases.

-

Metastases usually show increased uptake on bone scan.

|

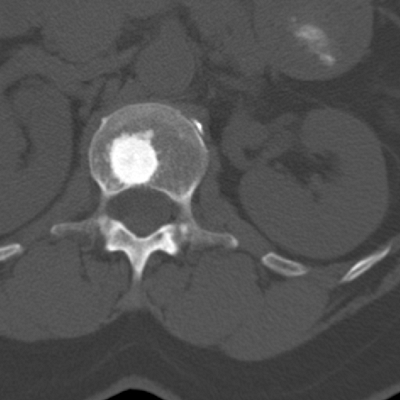

|

Figure 5.1-1 Enostosis in vertebral body. Note dense mineralization and thickened, radiating trabeculae.

|

Osteopoikilosis

-

Osteopoikilosis is an inherited autosomal

dominant disorder in which numerous enostoses are found, usually at the

ends of long bones. -

Similar to isolated enostosis, no uptake is seen on bone scan.

Osteopetrosis (Albers-Schönberg Disease)

-

This is typically a polyostotic disorder caused by an error in resorption of the primary spongiosum.

-

The hallmark is dense osteosclerosis filling the entire medullary canal, as opposed to isolated bone islands.

Enchondroma

-

A small enchondroma may be difficult to distinguish from an enostosis.

-

CT imaging should help distinguish the pattern of mineralization.

-

Enchondromas demonstrate incomplete

mineralization with a speckled or whorled pattern in contrast to the

dense, homogenous mineralization of enostoses. -

Enchondromas almost always demonstrate uptake on bone scan.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

-

No surgery is indicated; the main role of the consulting surgeon is to exclude other diagnostic possibilities.

Prognosis

-

Observed lesions rarely progress.

Osteoid Osteoma

Osteoid osteoma is a small, painful bone lesion that

most commonly occurs in the cortices of long bones, with a prediction

for the proximal femur. The pain pattern is usually distinctive, with

nightly pain rapidly alleviated with salicylates (aspirin). The lesion

has a characteristic small, radiolucent central nidus measuring up to 1

to 2 cm and thick, surrounding reactive bone. Standard treatment is

percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

most commonly occurs in the cortices of long bones, with a prediction

for the proximal femur. The pain pattern is usually distinctive, with

nightly pain rapidly alleviated with salicylates (aspirin). The lesion

has a characteristic small, radiolucent central nidus measuring up to 1

to 2 cm and thick, surrounding reactive bone. Standard treatment is

percutaneous radiofrequency ablation.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

-

Unknown

-

Postulated developmental error or vascular malformation rather than a true neoplasm

Epidemiology

-

Age of presentation: average 19 years (typical range 10 to 35 years)

-

Youngest patient: age 2 years

-

Male preponderance

Anatomic Location

-

Most commonly found in the long bones, especially the femur and tibia

-

Predilection for the proximal femur

-

Less common, subperiosteal lesions have been described on the surface of long bones.

-

-

Juxta-articular lesions: most common in the hip but have been described at many different articulations

-

Spine lesions

-

Lumbar more than cervical

-

Most common in posterior elements, typically in laminae

-

Pathophysiology

-

Presence of nerve fibers

-

Detected in the reactive zone and nidus of osteoid osteomas

-

Not seen in other bone tumors (osteoblastoma, osteosarcoma, etc.)

-

-

Increased levels of prostaglandins also detected within nidus

-

Increased vascular pressure due to prostaglandins may stimulate afferent nerves in nidus, causing pain.

-

May explain why salicylates provide such dramatic pain relief

-

Natural History

The nidus does not increase in size over time, although

reactive bone may become more prominent. Some authors have stated that

some osteoid osteomas “burn out” over time. Infrequent painless cases

have been described (1.6%

reactive bone may become more prominent. Some authors have stated that

some osteoid osteomas “burn out” over time. Infrequent painless cases

have been described (1.6%

P.121

in one review of 860 patients). Nevertheless, the actual incidence of spontaneous regression is difficult to document.

Diagnosis (Algorithm 5.1-1)

Clinical Features

-

Clinical hallmark of osteoid osteoma is pain at rest and especially night pain.

-

The pain is dramatically relieved by

salicylates (aspirin) typically within 20 to 25 minutes. While this is

a reliable sign, the absence of immediate relief does not rule out the

possibility of osteoid osteoma, as it occurs in only approximately 70%

of patients.

-

-

Symptoms typically occur for weeks to years before the patient seeks medical attention.

-

The pain may be referred to remote anatomic locations (e.g., femur lesion presenting with leg or knee pain).

-

Over time, symptoms gradually worsen, with an intermittent pain becoming a more constant ache.

-

Lesions in special anatomic locations may have different presentations.

-

Juxta-articular lesions

-

May present with monoarticular arthropathy consisting of joint effusion and synovitis

-

In prolonged cases, degenerative articular changes

-

-

Spinal locations

-

Usually present with painful scoliosis caused by muscle spasm

-

Lesion found at the concavity of the curve

-

-

Radiologic Features

Radiography

-

Small, sclerotic intracortical lesion with a central radiolucent nidus

-

Intracortical lesions: easy to detect on

plain radiography due to thick, dense reactive sclerosis. Often, the

central, radiolucent nidus is visible on radiographs if the appropriate

projection is obtained (Fig. 5.1-3).-

Intramedullary or endosteal lesions: less reactive bone formation and more difficult to diagnose radiographically (see Fig. 5.1-3)

-

Subperiosteal lesions: may be extremely difficult to see on plain radiographs

-

CT

-

CT is the definitive study modality, allowing for exact localization of nidus.

-

Protocol: thin (2-mm) cuts

-

Findings: The combination of thick,

uniform reactive bone surrounding a central, 1- to 2-cm or less

radiolucent nidus is highly suggestive of osteoid osteoma. -

Subperiosteal osteoid osteomas also have

a radiolucent nidus but incite a less dense, nonconfluent (“shaggy”)

reactive bone formation.

Bone Scan

-

Increased uptake is always identified in active osteoid osteomas.

-

Scintigraphy is very sensitive for

detecting the nidus and especially useful in subperiosteal and

intra-articular lesions, which may be missed on plain radiography.

Increased radiotracer activity is seen on immediate and delayed phases. -

“Double-density” sign: small focus of

increased activity corresponding to nidus surrounded by larger, less

intensely active region corresponding to the surrounding reactive bone

MRI

-

MRI is of questionable value, as the large area of marrow and soft tissue edema can obscure diagnosis.

-

It may be helpful in suspected cases of

juxta-articular osteoid osteoma, where intense marrow edema in only one

bone may be the initial clue.

Histologic Features

-

The nidus of osteoid osteoma is a small,

discrete lesion with disorganized seams of unmineralized or partially

mineralized osteoid with prominent osteoblastic and osteoclastic

activity. -

The spaces between the osteoid seams contain highly vascular, fibrous stroma.

-

Toward the periphery, the osteoid is more mature and dense with smaller osteoblasts.

|

|

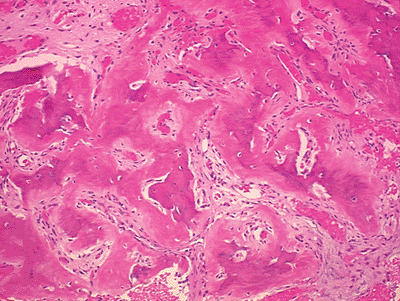

Figure 5.2-1

Histology for both osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma show similar disorganized woven bone with intervening fibrovascular stroma. |

Differential Diagnosis

Stress Reaction

-

Differentiating stress reaction (stress fracture) from osteoid osteoma is not an uncommon dilemma in young patients.

-

Both often present with unicortical periosteal reaction and pain.

-

The pain pattern is typically diurnal and

related to weight bearing on the affected extremity in stress reaction

and nocturnal and nonmechanical in osteoid osteoma. -

Reactive bone formation runs transverse to long axis of bone in stress reaction rather than parallel to it in osteoid osteoma.

P.122

|

|

Figure 5.1-3 Osteoid osteoma in proximal femur. (A,B)Classic intracortical osteoid osteoma with central nidus and thick, reactive bone formation. (C,D)Subperiosteal variant with almost normal plain radiographs and less vigorous reactive bone formation.

|

Chronic Osteomyelitis (Brodie’s Abscess)

-

Chronic osteomyelitis in bone may present with thick reactive bone formation and central lucency.

-

If there is a radiolucent central region, it is often larger than 2 cm.

-

Bone scan should be beneficial,

demonstrating center photopenia in infection, representing the necrotic

sequestrum, versus intense central uptake representing the nidus in

osteoid osteoma. -

MRI may not be helpful in distinguishing

the two as both infection and osteoid osteoma may demonstrate extensive

soft tissue and marrow edema.

Enostosis

-

Enostosis also appears as a sclerotic intraosseous lesion but should be painless and lacking uptake on scintigraphy.

-

Also helpful should be the brush borders of thickened trabeculae emanating from central, sclerotic core seen on CT in enostosis.

P.123

Osteoblastoma

-

Although osteoblastoma is commonly

grouped in the differential diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, it is a

radiographically and histologically distinct entity. -

It is larger, with the nidus of osteoid

osteomas rarely exceeding 2 cm in size, and comparatively only

partially mineralized with a thin, expansile rim of sclerotic bone.

Intracortical Hemangioma

-

Hemangioma of bone is most common in the vertebral bodies, where it presents with vertical, thickened trabeculae.

-

It can also present as single or multiple sclerotic appendicular skeletal lesions.

-

While some patients may experience pain, the nocturnal pattern and response to salicylates help distinguish the two.

-

The lesions tend to be less well circumscribed, without the typical central lucent nidus.

Treatment

Surgical Management

-

Although there may be some capacity for

osteoid osteomas to spontaneously regress, in general definitive

operative or medical treatment is indicated for all symptomatic osteoid

osteomas.

Preferred Treatment

-

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is

performed as an outpatient procedure under CT guidance. Heat generated

in the tissues near the tip of the probe necroses a small portion of

bone and, presumably, the nidus. -

Contraindications include spinal lesions

near cord or nerve root, subchondral lesions near articular surface,

and inaccessible lesions.

Alternative Treatment

-

Intralesional resection of the nidus (curettage)

-

Indications include recurrent tumors not amenable to repeat RFA and lesions for which the diagnosis is in doubt.

-

The main surgical challenge is locating the small nidus intraoperatively. Several techniques have been described:

-

Preoperative CT-guided localization via an implanted wire

-

Intraoperative nuclear scintigraphy (preoperative dye administration)

-

Preoperative fluorescent tetracycline labeling

-

Medical Treatment

-

Salicylates or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs)

-

Median duration of treatment before resolution of symptoms: 30 months

Results and Outcome

-

The success rate of RFA is 80% to 90%. If initial treatment is unsuccessful, a second procedure is successful in most instances.

-

Success rate for open curettage has been reported to be approximately 90%.

-

Scoliosis induced by osteoid osteoma corrects after treatment of osteoid osteoma.

-

The use of NSAIDs alone was reported to

result in resolution of symptoms in approximately 70% of patients after

a mean of 2.5 years in one study.

Osteoblastoma

Osteoblastoma is a benign, locally aggressive bone

neoplasm in which abundant, plump osteoblasts produce disorganized and

immature osteoid. It appears as a radiolucent, sometimes expansile,

lesion with hazy mineralization and a thin sclerotic rim. It has a

predilection for the spine and tends to recur if not completely excised.

neoplasm in which abundant, plump osteoblasts produce disorganized and

immature osteoid. It appears as a radiolucent, sometimes expansile,

lesion with hazy mineralization and a thin sclerotic rim. It has a

predilection for the spine and tends to recur if not completely excised.

Pathogenesis

-

Etiology is unknown.

Epidemiology

-

1% of primary bone tumors and 3% of benign bone tumors

-

Peak occurrence is in the first to third decades, with 80% of cases occurring in patients under 30 years old.

-

Male:female ratio 2:1

-

Distribution

-

Predilection for the spine (60% to 70% of cases)

-

Equally in cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions

-

More commonly in the posterior elements (66% in one series)

-

Nonaxial tumors can be found in round or flat bones as well as cranial bones

-

Within the long bones, metaphyseal = diaphyseal, proximal femur >mt distal femur, proximal tibia

-

Also in juxtacortical or periosteal

locations, with an appearance somewhat analogous to osteoid osteoma,

except with a much larger, central lucent area

-

-

Natural History

Although histologically similar in some respects to

osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma is a distinct entity with a different

natural history—one of progression rather than stasis or regression. A

range of manifestations has been observed, from indolent growth to

aggressive local growth.

osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma is a distinct entity with a different

natural history—one of progression rather than stasis or regression. A

range of manifestations has been observed, from indolent growth to

aggressive local growth.

In aggressive tumors, there is a tendency for multiple

recurrences over a long period of time. Disease-free periods of up to

17 years have been reported. One patient had 11 surgeries over 30

years. However, even with multiple recurrences,

recurrences over a long period of time. Disease-free periods of up to

17 years have been reported. One patient had 11 surgeries over 30

years. However, even with multiple recurrences,

P.124

the tumor typically remains benign. Nevertheless, rare cases of sarcomatous transformation have been described.

Diagnosis (See Algorithm 5.1-1)

Clinical Features

-

Pain is a typical symptom.

-

Often it is dull and aching.

-

Duration of 6 to 12 months before diagnosis

-

Rarely discovered incidentally

-

Nocturnal pain, like that seen in osteoid osteoma, is rare.

-

Not relieved by salicylates or NSAIDs

-

-

Physical examination reveals tenderness over tumor site.

-

Spinal osteoblastomas can cause painful scoliosis.

-

Objective neurologic findings in 29% of patients in one series

-

Deficits mostly minimal (e.g., muscle

weakness, sensory disturbance, or abnormal reflexes), although two

patients had neurogenic bladders and paraparesis

-

Radiologic Features

Radiographs

-

Typical appearance is of radiolucent lesion with faint densities.

-

A large range of radiographic appearances have been noted.

-

Cortical expansion is common, especially in the spine (Fig. 5.1-4), where there may be a significant aneurysmal component.

-

Dense mineralization may be seen in longstanding lesions or after radiotherapy.

-

Reactive bone formation is seen in lesions arising in cortex and less so with intramedullary lesions.

-

CT

-

CT scanning shows more detail, outlining

more clearly the sclerotic rim surrounding and separating the lesion

from adjacent soft tissues or surrounding bone. -

CT is also better for showing the sometimes subtle hazy mineralization of the lesion itself (see Fig. 5.1-3).

Histologic Features (See Fig 5.1-2)

-

Disorganized seams of abundant osteoid production in the form of woven bone

-

Similar to that of the central nidus in

osteoid osteoma but without the tendency toward more organized, mature

trabeculae seen toward the periphery -

“Epithelioid” osteoblasts (rounded and larger than normal)

-

-

Frequently seen: vascular spaces and giant cells, the latter of which are not normally seen in osteoid osteoma

P.125

|

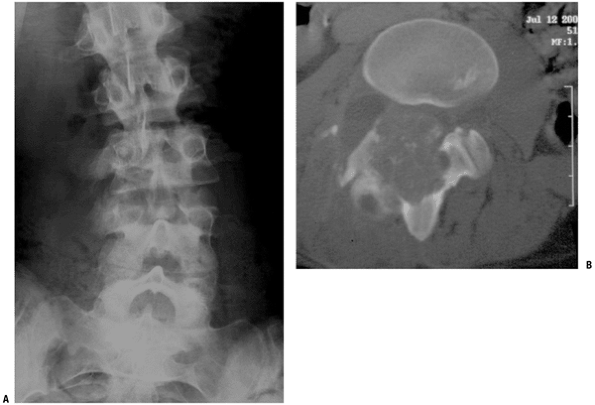

|

Figure 5.1-4 Osteoblastoma in lumbar spine. (A) Plain radiograph showing expansile, osteoblastic lesion with scoliosis.The lesion is in concavity. (B) CT scan showing expansile lesion in posterior spinal elements with faint calcifications and thin, incomplete sclerotic rim.

|

Differential Diagnosis

Osteoid Osteoma

-

Clinically, the characteristic nocturnal pain of osteoid osteoma is not typical of osteoblastoma.

-

No distinct small nidus is seen on imaging studies.

-

Histologically, the large vascular spaces and giant cells seen in osteoblastoma are not common in osteoid osteoma.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

-

These can resemble osteoblastoma radiographically and histologically.

-

In particular, osteoblastomas have a known propensity for secondary aneurysmal cyst formation.

-

If osteoblastoma is suspected in a

resected aneurysmal bone cyst, thorough sampling of the tumor is

necessary to locate what may be only a small, focal area of

osteoblastoma. -

Disorganized osteoid seams and osteoblastic proliferation should be absent in primary aneurysmal bone cyst.

Giant Cell Tumor of Bone

-

The similarity in the age of presentation

of the two tumors and the presence of giant cells on histological

examination of osteoblastoma may be a source of confusion. -

No mineralization is found in giant cell tumor.

-

Further, giant cell tumor is less common in the spine and more common anteriorly, in the vertebral bodies, when it does occur.

Chondroblastoma

-

Chondroblastoma may also present as an intraosseous lesion with stippled radiodensities.

-

It is almost exclusively seen in the epiphyses of long bones.

-

Histology also shows immature cartilage (chondroid), not seen in osteoblastoma.

Low-Grade Osteosarcoma

-

Imaging studies should be distinctive,

with conventional osteosarcoma rarely showing a sclerotic rim and

dense, surrounding, reactive bone formation. -

Disorganized and immature osteoid is seen

in osteosarcoma, but the hallmarks of malignancy (e.g., cellular and

nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses) are absent in osteoblastoma.

Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Recommended Treatment

-

Complete intralesional resection is recommended.

-

The use of a physical adjuvant, such as phenol or liquid nitrogen, may help reduce the risk of recurrence.

-

Wide resection may be considered in expendable bones such as rib, fibula, or metacarpals.

Indications

-

All tumors undergo surgical resection due to natural history of progressive growth and worsening symptoms in untreated tumors.

Adjuvant Treatments

-

Adjuvant radiation has been used but

probably should be reserved for recurrent or inoperable lesions.

Radiation may increase the risk of sarcomatous transformation.

Results and Outcome

Complete excision is typically curative. Local

recurrence is higher in difficult anatomic locations, such as the

spine. In one series of 23 patients across multiple institutions, two

recurrences were reported, one patient with a disease-free interval of

17 years and one patient who had 11 operations over 27 years. In

another series of 53 patients with more than 1 year of follow-up, 3 of

27 of spinal lesions recurred, 2 in patients who received adjuvant

radiation, and 4 of 15 extremity lesions recurred, 1 in a patient who

received postoperative radiation.

recurrence is higher in difficult anatomic locations, such as the

spine. In one series of 23 patients across multiple institutions, two

recurrences were reported, one patient with a disease-free interval of

17 years and one patient who had 11 operations over 27 years. In

another series of 53 patients with more than 1 year of follow-up, 3 of

27 of spinal lesions recurred, 2 in patients who received adjuvant

radiation, and 4 of 15 extremity lesions recurred, 1 in a patient who

received postoperative radiation.

Cases of mortality and amputation have been reported due

to aggressive and repeated local growth of the tumor in the spine and

extremities.

to aggressive and repeated local growth of the tumor in the spine and

extremities.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge research assistance by Brittany

L. Rice, MLS, AHIP, and Smita Jhaveri at the Suburban Hospital Medical

Library.

L. Rice, MLS, AHIP, and Smita Jhaveri at the Suburban Hospital Medical

Library.

Suggested Reading

Beauchamp CP, Duncan CP, Dzus AK, et al. Osteoblastoma: experience with 23 patients. Can J Surg 1992;35:199–202.

Greenspan

A. Benign bone-forming lesions: osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and

osteoblastoma. Clinical, imaging, pathologic, and differential

considerations. Skel Radiol 1993;22:485–500.

A. Benign bone-forming lesions: osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and

osteoblastoma. Clinical, imaging, pathologic, and differential

considerations. Skel Radiol 1993;22:485–500.

Greenspan A. Bone island (enostosis): current concept—a review. Skel Radiol 1995;24:111–115.

Ilyas I, Younge DA. Medical management of osteoid osteoma. Can J Surg 2002;45:435–437.

Marsh BW, Bonfiglio M, Brady LP, et al. Benign osteoblastoma: range of manifestations. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1975;57:1–9.

Nemoto O, Moser RP, Van Dam BE, et al. Osteoblastoma of the spine: a review of 75 cases. Spine 1990;15:1272–1280.

O’Connell JX, Nanthakumar SS, Nielsen GP, et al. Osteoid osteoma: the uniquely innervated bone tumor. Mod Pathol 1998;11:175–180.

Rimondi

E, Bianchi G, Malaguti MC, et al. Radiofrequency thermoablation of

primary non-spinal osteoid osteoma: optimization of the procedure. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1393–1399.

E, Bianchi G, Malaguti MC, et al. Radiofrequency thermoablation of

primary non-spinal osteoid osteoma: optimization of the procedure. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1393–1399.

Sciubba JJ, Younai F. Ossifying fibroma of the mandible and maxilla: review of 18 cases. J Oral Pathol Med 1989;18:315–321.

Shankman S, Desai P, Beltran J. Subperiosteal osteoid osteoma: radiographic and pathologic manifestations. Skel Radiol 1997;26:457–462.

Torriani M, Rosenthal DI. Percutaneous radiofrequency treatment of osteoid osteoma. Pediatr Radiol 2002;32:615–618.

Vanhoenacker FM, De Beuckeleer LH, Van Hul W, et al. Sclerosing bone dysplasias: genetic and radioclinical features. Eur Radiol 2000;10:1423–1433.