Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Chris Hutchins MD

John H. Wilckens MD

Description

-

TOS is a group of signs and symptoms that

result from compression of the neurovascular supply to the upper limb

in the supraclavicular area and shoulder girdle (1). -

Synonyms: Scalene anticus syndrome;

Costoclavicular syndrome; Hyperabduction syndrome; Cervical rib

syndrome; Droopy shoulder syndrome

Epidemiology

Incidence

-

Incidence unknown

-

Condition not common

Prevalence

-

Most common in young to middle-aged adults

-

Occurs more often in females than males

Risk Factors

-

Cervical ribs

-

Congenital fibrous bands

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Thyroid disease

-

Alcoholism

-

Aggravating factors:

-

Obesity

-

Extremely large breasts in females

-

Emotional depression, causing patients to adopt a slumping posture

-

Repetitious overhead activity

-

Etiology

-

Frequently multifactorial and may be

influenced by trauma, repetitious job activities, anatomic predisposing

factors, and some systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes, thyroid disease) -

A job that requires continuous overhead

activity (e.g., painting ceilings) may cause signs and symptoms of

brachial plexus compression over a short period. -

A job that requires repetitive motions of

the upper extremities, but in less extreme elevation (e.g., keyboard

operator, truck driver), may cause similar symptoms, but over a period

of years.

Associated Conditions

-

CTS and cubital tunnel syndrome complaints:

-

It is believed that a nerve that has some

degrees of compression in the neck is more sensitive to nerve

compression problems at other points along its course, such as at the

elbow or the wrist. -

Thus, patients with TOS are more susceptible to developing CTS and cubital tunnel syndromes, and vice versa.

-

This phenomenon has been termed the “double crush syndrome.”

-

-

Patients with arthritis, diabetes

mellitus, thyroid disease, and alcoholism have nerves with increased

susceptibility to the development of superimposed nerve compression.

Signs and Symptoms

-

Neural compression:

-

Patients may complain of pain in the neck

or shoulder, and numbness and tingling involving entire upper limb or

forearm and hand (Fig. 1).-

The ulnar side of the limb and the 2 ulnar digits are involved predominantly, although the middle finger also may be included.

-

Sensory findings often are subtle, are

usually on the ulnar aspect of the hand, and may include the medial

aspect of the forearm.

-

-

Nocturnal pain and paresthesias are

common and must be differentiated from symptoms caused by CTS, which

commonly affects the radial side of the hand. -

Frequently, patients experience

difficulty in using the limb in an elevated, overhead position, such as

when holding a hair dryer. -

Some patients show a decline in the strength or dexterity of the hand, even without obvious atrophy.

-

Headache and pain in the arm, shoulder, neck, and chest may accompany any of these other complaints.

-

-

Arterial compression:

-

Coolness

-

Weakness

-

Easy fatigability of the arm

-

Diffuse pain

-

Occasionally, Raynaud-like symptoms

-

-

Venous compression:

-

May be intermittent or, less frequently, constant

-

Results in limb swelling

-

Varying degrees of cyanosis

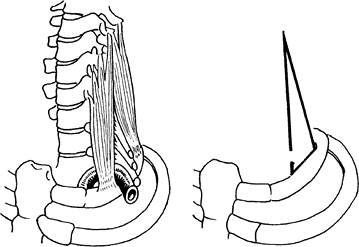

Fig. 1. In TOS, the brachial plexus or subclavian artery (left) may be compressed in the scalene triangle (right) or by an extra rib.

Fig. 1. In TOS, the brachial plexus or subclavian artery (left) may be compressed in the scalene triangle (right) or by an extra rib.

-

Physical Exam

-

The diagnosis of TOS is a clinical one (2).

-

Assess the neck and supraclavicular fossa on both sides.

-

The affected scapula may be held lower and more anteriorly than the opposite scapula.

-

The clavicle may appear more horizontal than normal.

-

Tenderness may be present over the brachial plexus.

-

-

Tinel sign may be present (pain referred to the ulnar aspect of the hand).

-

Examine the shoulder girdle for glenohumeral instability, which may produce symptoms similar to those of TOS.

-

Perform a complete, bilateral, upper extremity motor and sensory examination.

-

Test the intrinsic muscle strength in the hand.

-

Document the vasomotor status of the limb and the presence or absence of swelling.

-

“Stress tests” or provocative maneuvers used in the clinical diagnosis of TOS:

-

These tests must be interpreted

carefully. (It is not clinically significant, for example, to be able

merely to obliterate the pulse by some position of the arm, because

doing so is possible in many asymptomatic people.) -

A test is not positive unless, without

prompting, the patient complains of reproduction of the symptoms when

the arm is placed in the provocative position. -

Conduct the Adson maneuver with the

patient’s arm at the side, the neck hyperextended, and the head turned

toward the affected side. -

Perform the Wright maneuver with the patient’s arm abducted and externally rotated.

-

The test is more sensitive when the patient holds a deep breath.

-

The patient’s elbow should be extended to

limit the effects of possible ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (which

would be exacerbated by elbow flexion).

-

-

P.447

Tests

Imaging

-

Radiography

-

Obtain plain AP and lateral radiographs

of the cervical spine to evaluate for discogenic disease, adventitious

ribs, or overly long transverse processes. -

Evaluate the chest radiograph for apical

lung tumors, which may be responsible for neurovascular compression,

especially in patients with a history of smoking. -

MRI is useful if a strong suspicion exists of disc disease, but it does not help in the diagnosis of TOS.

-

-

Electrodiagnostic studies may be helpful in identifying associated CTS and cubital tunnel syndrome.

-

Vascular studies if compression of the subclavian artery or vein is suspected

Pathological Findings

Compression of the neurovascular supply to the upper limb in the region of the suprascapular area and shoulder girdle is noted.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Lesions of the cervical spine:

-

Degenerative disc disease

-

Cervical spondylosis

-

-

Lesions compressing the brachial plexus (e.g., tumors of the apex of the lung)

-

Trauma

-

Compression of the peripheral nerves:

-

CTS (entrapment neuropathy of the median nerve)

-

Ulnar nerve compression or dislocation at the elbow

-

Compression of the radial or suprascapular nerves

-

-

Neuropathies of alcoholism, heavy metal intoxication, avitaminosis, or diabetes mellitus

-

Complex regional pain syndromes

-

Arterial lesions:

-

Peripheral or coronary atherosclerosis

-

Aneurysm

-

Occlusive changes

-

Embolism

-

Raynaud disease

-

Vasculitis

-

-

Venous lesions:

-

Effort vein thrombosis

-

Thrombophlebitis

-

General Measures

Nonoperative management should be tried initially for all patients with TOS (3).

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

The cornerstone of nonoperative therapy

is a carefully regulated program of muscle strengthening and postural

re-education exercises. -

The trapezius, rhomboid, and levator

scapulae muscles can be strengthened by the use of elastic bands or

free weights with the arms elevated <90° and with avoidance of

bracing of the scapulae to prevent provocative positions. -

Patients often do not experience symptomatic improvement before 2 months.

-

Exercises must be continued until muscular atrophy and weakness is reversed and correct posture is developed.

-

The preoperative exercise routine can be resumed 1 month postoperatively.

Medication

-

Nonoperative therapy is based on a stringent program of exercises to strengthen the muscles of the pectoral girdle.

-

The goal is to augment the tone of the suspensory muscles of the AC joint so the costoclavicular space can remain wide.

-

Patients must continue with the exercises

until they have reversed the muscular atrophy and weakness and have

developed an awareness of correct posture. -

If a carefully supervised exercise and postural program fails, and the patient has intractable pain, surgery may be indicated.

-

Surgery should be presented as an option

only for those patients who believe that they cannot continue with the

condition as it is and who understand the potential risks and benefits

of the proposed procedure.

-

-

Explanation of the pathologic process of

TOS helps to alleviate a patient’s concerns and makes the patient more

receptive when instructed to avoid certain activities and postures.-

Specific contributory factors, such as

repetitive elevated positioning of the arms at work, should be

identified and, when possible, addressed.

-

Surgery

-

Scalenectomy or 1st rib resection, or

some combination thereof, represents the most common surgical treatment

for patients with TOS. -

A patient with an arterial or venous lesion may require vessel repair or grafting in addition to decompression.

Prognosis

-

Nonoperative management is successful in most patients.

-

With proper selection of patients for surgery, most improve.

Complications

-

Pneumothorax

-

Infection

-

Vascular injury

-

Injury to brachial plexus

-

Shoulder girdle instability

Patient Monitoring

-

Follow the patient’s physical therapy progress.

-

Postoperative disease recurrence is

possible, secondary to scapular muscle weakness and an inability to

support the shoulder girdle or inadequate release of the site of

compression.

References

1. Fechter JD, Kuschner SH. The thoracic outlet syndrome. Orthopaedics 1993;16:1243–1251.

2. Abdollahi

K, Wood VE. Shoulder. Section O. Thoracic outlet syndrome. In: DeLee

JC, Drez D, Jr, Miller MD, eds. DeLee & Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports

Medicine: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders,

2003:1161–1169.

K, Wood VE. Shoulder. Section O. Thoracic outlet syndrome. In: DeLee

JC, Drez D, Jr, Miller MD, eds. DeLee & Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports

Medicine: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders,

2003:1161–1169.

3. Roos DB. The thoracic outlet syndrome is underrated. Arch Neurol 1990;47:327–328.

Additional Reading

Leffert RD. TOS. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1994;2:317–325.

Codes

ICD9-CM

353.0 Thoracic outlet syndrome

Patient Teaching

-

Explain the pathogenesis of TOS to

patients, because an understanding of the mechanism helps the patient

recognize the need for modifying activities and postures that would

narrow the thoracic outlet, such as overhead movements, hyperabduction

of the arm, use of shoulder straps, and carrying heavy handbags. -

Attempts to alter the ergonomic characteristics of the job should be made, or a new job should be considered.

Prevention

-

No known fully effective means of prevention

-

The patient can diminish the risk by avoiding frequent overhead lifting or hyperabduction of the arm and by weight control.

FAQ

Q: What are the most common signs and symptoms of TOS?

A:

Pain, weakness, fatigability, numbness, and tingling in the upper

extremity. These symptoms may be intermittent and have inconsistent

presentations. A high clinical suspicion is needed, and definitive

diagnosis may require several studies.

Pain, weakness, fatigability, numbness, and tingling in the upper

extremity. These symptoms may be intermittent and have inconsistent

presentations. A high clinical suspicion is needed, and definitive

diagnosis may require several studies.

Q: Do all patients with TOS require surgery?

A:

Although most patients respond to physical therapy and postural

education, those with anatomic lesions and overhead occupations or

recreations are best treated with surgery.

Although most patients respond to physical therapy and postural

education, those with anatomic lesions and overhead occupations or

recreations are best treated with surgery.