Giant Cell Tumor

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Giant Cell Tumor

Giant Cell Tumor

Uma Srikumaran MD

Frank J. Frassica MD

Description (1,2,3)

-

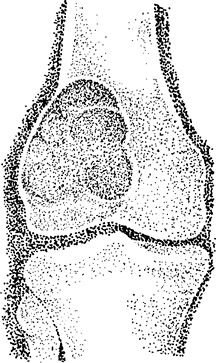

A benign but often locally aggressive

neoplasm, characterized by large numbers of uniformly distributed,

osteoclastlike giant cells and a background population of plump,

epithelioid-to-spindle mononuclear cells (Fig. 1) -

The vast majority of these tumors are located near the articular end of a tubular bone; ~50% occur in the knee.

-

Other frequently involved sites:

-

Distal radius

-

Proximal femur

-

Proximal humerus

-

Distal tibia

-

Sacrum

-

-

Flat-bone involvement tends to occur in the sacrum and pelvis.

-

Giant cell tumors complicating Paget disease often involve the flat bones, particularly those of the craniofacial region.

-

Multifocal giant cell tumors are rare.

-

Classification: Musculoskeletal Tumor

Society surgical staging system (also known as the “Enneking” system

[1,4]), a grading system that may have prognostic importance:-

Stage I (<5% of patients):

-

Virtually asymptomatic and often discovered incidentally

-

Occasionally may cause pathologic fracture

-

Has a sclerotic rim on a plain radiograph or CT scan

-

Is relatively inactive on a bone scan

-

Is histologically benign

Fig.

Fig.

1. A giant cell tumor arises in the epiphysis but may expand into the

metaphysis. The distal femoral epiphysis is one of the most common

sites.

-

-

Stage II (70–85% of patients):

-

Symptomatic

-

May be associated with pathologic fracture

-

Has an expanded cortex but no breakthrough on a plain radiograph

-

Is active on a bone scan

-

Is histologically benign

-

-

Stage III (10–15% of patients):

-

Symptomatic, rapidly growing mass

-

Has cortical perforation with an accompanying soft-tissue mass on a plain radiograph or CT scan

-

Its activity on a bone scan extends beyond the lesion seen on a plain radiograph.

-

Shows intense hypervascularity on angiography

-

Is histologically benign, although one

may see tumor infiltration of the peritumoral capsule with violation of

the cortex and extension into the surrounding soft tissues

-

-

Epidemiology

Incidence

The peak incidence is in the 3rd decade of life, with a gradual decline into late adulthood (3).

Prevalence (3)

-

Accounts for 5% of biopsied primary bone tumors and ~20% of benign bone tumors

-

It is the 6th most common primary osseous neoplasm.

-

It almost always affects the mature skeleton with closed epiphyseal plates.

-

~10–15% of patients are <20 years old, but almost all are skeletally mature.

-

The onset of giant cell tumor after 55 years of age is rare.

-

<2% of these tumors occur adjacent to

open epiphyses; the diagnosis of giant cell tumor in a skeletally

immature patient therefore must be questioned. -

Females are affected 1.3–1.5 times as often as males.

Risk Factors

Paget disease (rare association)

Etiology

Rare cases may result as a complication of pre-existing Paget disease of bone.

Associated Conditions

-

Rarely, giant cell tumors may complicate Paget disease of bone.

-

More frequently, secondary aneurysmal bone cyst formation may be associated with giant cell tumors.

Signs and Symptoms (2,3)

-

Complaints usually are nonspecific, and patients often have joint symptoms.

-

90% of patients complain of pain, often with accompanying mass or swelling.

-

5–10% of patients present with pathologic fracture.

-

Serum chemistry studies typically are normal.

Physical Exam

-

A physical examination is not specific for this condition.

-

In general, tenderness over the epiphyseal end of a bone adjacent to a joint is noted.

-

An effusion or restriction of joint motion may be present if the tumor has nearly violated the cortex.

Tests

Lab

Serum calcium and phosphate levels should be checked to exclude hyperparathyroidism.

Pathological Findings (1)

-

The tumor has a background of

proliferating, homogeneous mononuclear cells, which are round to ovoid,

have relatively large nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli, and display

multinucleated giant cells dispersed evenly throughout the tissue. -

Mitotic figures may be common.

-

It may have an aneurysmal bone cyst component, and it may invade blood vessels.

-

Involutional changes with lipid-filled histiocytes may be observed.

Imaging (1,2)

-

Radiography:

-

Plain radiographs show an eccentric, expanding zone of radiolucency, frequently at the end of a long bone.

-

Usually, no reactive sclerosis is present.

-

The tumor often begins in the metaphysis and extends to the articular surface.

-

Almost invariably, it involves the epiphysis, usually with metaphyseal extension.

-

If the spine is affected, it usually is the anterior vertebral body.

-

The tumor is multicentric in only 1% of cases.

-

Chest radiography is performed because 2% of patients may have pulmonary metastases.

-

-

A bone scan often is positive, but the lesion may be inactive on a bone scan.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Giant cell reparative granuloma, or

“brown tumor” of hyperparathyroidism (The giant cell reparative

granuloma tumor contains a more uniform distribution of larger giant

cells with many more nuclei.) -

NOF

-

Benign fibrous histiocytoma

-

Aneurysmal bone cyst

-

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma

P.157

General Measures

Patients with large lesions are placed on crutches until definitive surgery.

Special Therapy

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy should be used only rarely for giant cell

tumors because its use increases the risk of malignant transformation

of the tumor.

tumors because its use increases the risk of malignant transformation

of the tumor.

Physical Therapy

Patients undergo physical therapy to regain their ROM and strength.

Surgery

-

Current technique involves a combination

of marginal resection and curettage using power burrs on the margins of

the cavity, followed by painting with full-strength phenol. -

Polymethylmethacrylate cement augmentation may be used to fill the cavity and to provide a rigid construct.

-

Cancellous bone grafting is used to restore the subchondral surface.

-

Internal fixation may be necessary to provide a rigid construct.

-

When the tumor is in an expendable bone,

such as the fibula, or is a recurrent lesion with joint destruction,

wide resection may be necessary. -

Reconstruction around the knee may involve resection arthrodesis, osteoarticular allograft, or prosthetic implantation.

-

Amputation may be indicated for neglected

tumors with substantial soft-tissue extension and, in rare instances,

for recurrent tumors.

Prognosis

-

Recurrence may occur in 40–60% of giant cell tumors treated by simple curettage alone.

-

Most recurrences occur within 2 years, and nearly all occur within 5 years.

-

The recurrence rate with modern treatment (exteriorization, power burr curettage, and adjuvant therapy) is ~10–15%.

Complications

-

A secondary malignant giant cell tumor results when a sarcoma develops at the site of a previously treated giant cell tumor.

-

In the past:

-

10–15% of patients with giant cell tumors treated with irradiation developed postirradiation sarcomas.

-

In comparison, ~5% of recurrent giant cell tumors not subjected to irradiation developed sarcomatous transformation.

-

Patient Monitoring

-

Because recurrence is common, patients should be followed closely postoperatively (every 3 months for 2 years).

-

A chest radiograph is taken once a year.

References

1. McCarthy

EF, Frassica FJ. Primary bone tumors. In: Pathology of Bone and Joint

Disorders: With Clinical and Radiographic Correlation. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders, 1998:195–275.

EF, Frassica FJ. Primary bone tumors. In: Pathology of Bone and Joint

Disorders: With Clinical and Radiographic Correlation. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders, 1998:195–275.

2. Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin North Am 2006;37:35–51.

3. Unni

KK. Giant cell tumor (osteoclastoma). In: Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General

Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases, 5th ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1996:263–283.

KK. Giant cell tumor (osteoclastoma). In: Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General

Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases, 5th ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1996:263–283.

4. Enneking

WF. Malignant skeletal neoplasms. In: Clinical Musculoskeletal

Pathology, 3rd ed. Gainsville: University of Florida Press,

1990:358–421.

WF. Malignant skeletal neoplasms. In: Clinical Musculoskeletal

Pathology, 3rd ed. Gainsville: University of Florida Press,

1990:358–421.

5. Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone. Am J Clin Oncol 2006;29:96–99.

6. Ward WG, Sr, Li G, III. Customized treatment algorithm for giant cell tumor of bone: Report of a series. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;397:259–270.

Codes

ICD9-CM

170.9 Giant cell tumor

Patient Teaching

-

The patient should understand the frequency of recurrence and the need for continued follow-up.

-

The patient also should understand that

the tumor is considered benign, but that in rare instances it may

metastasize to the lungs (2% risk).

FAQ

Q: Is a giant cell tumor a cancer?

A: Although giant cell tumors of bone may behave in an aggressive local fashion, the tumor is benign.

Q: Can a giant cell tumor spread to other sites?

A:

Occasionally (~2% of the time), a giant cell tumor can spread to the

lungs. This spread is a benign metastasis because only ~20% of patients

will die because of the spread.

Occasionally (~2% of the time), a giant cell tumor can spread to the

lungs. This spread is a benign metastasis because only ~20% of patients

will die because of the spread.

Q: Can a giant cell tumor come back after surgery?

A: Giant cell tumors are prone to recurrence. With the best treatment, the rate of recurrence is ~10–15%.