Camptodactyly

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Camptodactyly

Camptodactyly

Dawn M. LaPorte MD

Description

-

A nontraumatic flexion deformity of the PIP joint that may progress gradually (1,2)

-

Usually involves the little finger alone, but sometimes also affects adjoining fingers

-

May or may not be associated with a syndrome

-

2 recognized types: Early (develops in the 1st year of life) and delayed (or late; onset after age 10)

-

The early form is the more common, and it affects the genders equally.

-

The delayed form affects mostly girls.

-

Although these forms also are called

“congenital” and “adolescent,” respectively, some clinicians believe

the terms early and delayed (or late) should be used, because these

manifestations likely represent variations of the same condition.

-

-

The best results occur when treatment is initiated in childhood or adolescence.

-

The results of treatment initiated in adulthood are poor.

Epidemiology

Incidence

<1% of the population is affected (3).

Risk Factors

Family history

Genetics

Many cases are sporadic; others have simple autosomal dominance.

Pathophysiology

-

All structures that could possibly cause flexion deformity at the PIP joint have been considered possible deforming factors.

-

Findings may include:

-

Absence, atrophy, or abnormal insertion of the lumbricalis muscle into the lumbrical canal

-

A band of fibrous tissue arising from the A1 pulley and inserting into the flexor superficialis tendon

-

Origination of the flexor superficialis from the palmar fascia in the mid aspect of the palm

-

Anomalous tendons

-

Short flexor digitorum profundus

-

Contracture of the collateral ligaments or the volar plate

-

Etiology

-

Camptodactyly is caused by an imbalance between the flexor and extensor mechanisms of the PIP joint.

-

Anatomic anomalies occur frequently and

include abnormal insertions of the lumbricalis, flexor digitorum

superficialis, and retinacular ligaments.

Associated Conditions

-

Trisomy 13–15

-

Oculodentodigital syndrome

-

Orofaciodigital syndrome

-

Aarskog syndrome

-

Cerebrohepatorenal syndrome

-

Mucopolysaccharidosis

-

Osteo-onychodysostosis

-

Jacob-Downey syndrome

Signs and Symptoms

-

A flexion deformity of the PIP joint of the little finger

-

Digital angulation in the AP plane is not to be confused with clinodactyly, which describes angulation in the radioulnar plane.

-

Occasionally, flexion deformity of the PIP joint of adjoining fingers also occurs.

-

~2/3 of patients show bilateral involvement, with the degree of contracture not necessarily symmetric.

-

When only 1 hand is affected, it is usually the right one.

-

In children, the deformity usually disappears when the wrist is flexed.

-

The MCP joint usually is held in slight hyperextension.

-

In severe contractures, with rotatory

deformity in the digit, the patient may complain that the finger

interferes with tapping or gripping activities. -

Pain and swelling usually are absent, even with severe flexion contracture.

Physical Exam

-

The range of active and passive flexion

and extension of the PIP and MCP joints should be quantified, with the

wrist in both flexion and extension. -

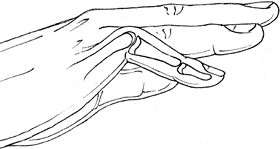

A flexible deformity should be differentiated from a fixed flexion contracture (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1. The flexion deformity seen in camptodactyly.

|

Tests

Imaging

-

Plain films of the digit should be obtained.

-

Radiographic changes that occur with time

and growth include broadening of the base of the middle phalanx,

indentation of the neck of the proximal phalanx, a narrowed joint

space, and dorsal flattening of the condyle of the proximal phalanx

with flattening of the palmar surface. -

These findings bode poorly for chances of correcting the clinodactyly.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Differentiation is based on a thorough history and physical examination.

-

Clinodactyly, which describes digital angulation in the radioulnar plane

-

Trauma residual

-

Dupuytren contracture

-

Arthrogryposis

-

Absence or hypoplasia of an extensor tendon

-

Marfan syndrome

-

Beal syndrome (contractural arachnodactyly)

-

Pterygium syndrome

-

Symphalangism

-

Boutonniere deformity

-

General Measures

-

No single successful treatment exists because no single cause of the condition exists.

-

Treatment is designed to restore normal flexor–extensor balance.

-

In the early form, normal balance may be achieved best by progressive extension splinting.

-

In the delayed form, surgery often is indicated if splinting fails and the deformity is severe or progressive.

-

-

Best results are obtained with surgical treatment in young patients, but the outcome is not completely predictable.

-

Because the results of treatment in adults are poor, corrective operations in adults are no longer recommended.

-

For most activities, dysfunction remains

so slight that many surgeons discourage surgery because the results of

operative treatment are unpredictable. -

A contracture of <30–40° does not interfere with function.

-

The patient and family should be advised to accept the deformity and avoid surgical intervention (4,5).

-

Splinting or serial plaster casting should be tried before surgery.

-

-

Patients with marked contracture may need corrective treatment; the decision should be left up to the patient.

-

Medical treatment:

-

Splinting

-

Serial casting

-

P.53

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Occupational therapy may help those with early (congenital) or late (adolescent) camptodactyly.

-

The occupational therapist may supervise

stretching and splinting. Static splinting at night is recommended to

prevent progression.

Surgery

-

Surgery is designed to correct the aberrant anatomy through release or transfer of abnormal origins or insertions.

-

Unfortunately, the results of these procedures are often disappointing.

-

Tendon transfer may be considered for adolescent camptodactyly.

-

If radiographs reveal bone and joint

changes, corrective extension osteotomy is indicated, rather than

procedures designed to increase motion through the joint itself.

Prognosis

-

Left untreated, the condition will worsen progressively in 80% of cases.

-

The deformity often worsens during growth spurts.

-

The condition usually does not progress after the age of 18–20 years.

Complications

Surgery in adults may produce increased joint stiffness and pain.

Patient Monitoring

-

The deformity may progress with growth spurts.

-

Successful treatment is greatest at younger ages; therefore, it is best to treat early and to monitor the patient’s progress.

References

1. Flatt AE. Crooked fingers. In: The Care of Congenital Hand Anomalies. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, Inc., 1994:196–227.

2. Senrui

H. Congenital contractures. In: Buck-Gramcko D, ed. Congenital

Malformations of the Hand and Forearm. London: Churchill Livingstone,

1998:295–309.

H. Congenital contractures. In: Buck-Gramcko D, ed. Congenital

Malformations of the Hand and Forearm. London: Churchill Livingstone,

1998:295–309.

3. Kozin

SH, Kay SP. Congenital contracture. Camptodactyly. In: Green DP,

Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al., eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery,

5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005:1512–1521.

SH, Kay SP. Congenital contracture. Camptodactyly. In: Green DP,

Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al., eds. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery,

5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005:1512–1521.

4. McCarroll HR. Congenital anomalies: a 25-year overview. J Hand Surg 2000;25A:1007–1037.

5. Siegert JJ, Cooney WP, Dobyns JH. Management of simple camptodactyly. J Hand Surg 1990;15B:181–189.

Additional Reading

Milford L: Congenital anomalies. In: Crenshaw AH, ed. Campell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 7th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1987:419–450.

Waters PM: Wrist and hand: pediatric aspects. In: Kasser JR, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update 5: Home Study Syllabus. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1996:293–309.

Codes

ICD9-CM

755.59 Camptodactyly

Patient Teaching

-

Skin monitoring around splints is important.

-

Stretching should be continued after the splinting or casting program to maintain the gain achieved.

Activity

-

Generally, no limitations are placed on activity.

-

In severe cases, the deformity may pose a problem in sports or occupations requiring fine work with the hands.

Prevention

No effective means of prevention exists.

FAQ

Q: How often does camptodactyly affect both hands?

A: It is bilateral in ~2/3 of cases; the 5th finger is most commonly involved.

Q: Is surgery recommended to correct the deformity?

A:

Mild contracture (<30–40°) does not interfere with function and

should be treated nonoperatively. Surgical results are not consistent,

and surgery usually is reserved for more severe cases that hinder

activity.

Mild contracture (<30–40°) does not interfere with function and

should be treated nonoperatively. Surgical results are not consistent,

and surgery usually is reserved for more severe cases that hinder

activity.