Osteoarthritis and Inflammatory Arthritis of the Hip

– HIP > Part B – Evaluation and Treatment of Hip Disorders > 3 –

Osteoarthritis and Inflammatory Arthritis of the Hip

frequently encountered diseases in orthopaedics. They are the leading

causes of joint disease in the hip, resulting in joint destruction, and

often in the need for hip replacement. Symptomatic osteoarthritis of

the hip is prevalent in 3% to 5% of the adult white population.

Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis is more common (9% to 10%),

indicating that roughly half of the patients with some radiographic

evidence of osteoarthritis are asymptomatic.

still often used, that implies degenerative changes owing to various

causes. The term DJD can be confusing because it is often used

synonymously for osteoarthritis, but can be applied to any condition

that results in degenerative changes of the joint. A more correct use

of terminology would be to avoid the use of DJD and use the correct

underlying diagnosis instead.

grouped into noninflammatory and inflammatory arthritis. Osteoarthritis

is by far the most common condition of the noninflammatory group.

Osteoarthritis results from a primary failure of the cartilage, whereas

with inflammatory arthritis, the cartilage failure is secondary to the

inflammatory response. Table 3-1 outlines the more common arthritides that can affect the hip joint.

multitude of conditions, with the end result being failure of the

weight-bearing cartilage. Because of its various potential causes, OA

can be thought of as a syndrome rather than a single entity. In the

past, it was felt that most patients who developed osteoarthritis had

primary OA without any identifiable cause, arising as a result of a yet

unidentified weakness of the cartilage. Now, it is more evident that

most patients with OA likely have an underlying mechanical cause that

results in damage and subsequent degeneration of cartilage. However,

still there are patients in whom no cause can be clearly identified,

and these may represent a biologic condition that results in cartilage

failure. These patients represent primary osteoarthritis, which can be

considered a diagnosis of exclusion.

understanding of various mechanical problems, which may be termed

prearthritic conditions, whose natural histories show progression to

osteoarthritis. These conditions include mild hip dysplasia as well as

femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). FAI has become recognized as a

mechanical abnormality of the hip in which the anterior femoral neck

impinges on the acetabulum, leading to shear damage of the articular

cartilage. Two types of impingement have been described: cam type and

pincer type. Originally felt to possibly represent an asymptomatic or

subclinical slipped epiphysis, the cam type of impingement has been

shown to be a developmental abnormality. During development the femoral

head epiphysis and trochanteric apophysis share one physis, which

separates into two distinct growth plates around 4 years of age. A

delayed separation or abnormal, eccentric closure results in an

abnormal morphology typically affecting the anterolateral femoral neck.

The effect is a decreased head/neck offset, reducing the head/neck

ratio in this region and resulting in impingement of the anterior

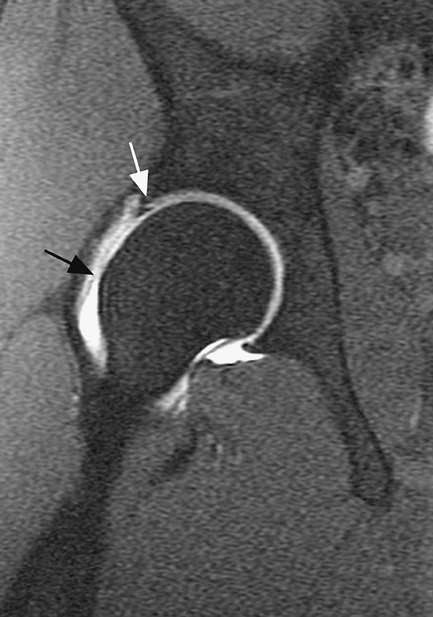

femoral neck with the anterior rim of the acetabulum (Fig. 3-1).

The pincer type of impingement is more a result of an acetabular

abnormality. Approximately 16% of dysplastic acetabula are retroverted.

This retroversion results in a relatively prominent anterior rim, also

causing impingement in flexion. Additionally, a deep acetabulum (coxa

profunda) may result in a prominent acetabular rim, causing

impingement. Both cam and pincer types of impingement may coexist.

|

TABLE 3-1 Arthritides Affecting the HIP

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

types of inflammatory arthritides. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most

common form of inflammatory arthritis. It has a prevalence of 0.3% to

1.5% in North America and is approximately 2.5 times more common in

women. The cause is thought to be an autoimmune cell-mediated response.

Further pathogenesis is discussed later. The inciting event that begins

the inflammatory response has yet to be identified, but is likely an

extrinsic factor (e.g., infectious, environmental) in a genetically

susceptible host. A genetic predisposition (HLA-B27) has also been

shown in seronegative (defined as rheumatoid factor–negative)

arthropathies; however, an infectious cause has been more closely

linked to certain types. Reactive and enteric spondyloarthropathies

have been associated with various gastrointestinal and genitourinary

infections.

factor responsible for most osteoarthritis, there are epidemiologic

factors as well. These epidemiologic factors may result in a

predisposition of the joint to osteoarthritis as a result of altered

mechanics or other yet to be defined biologic factors. Family and twin

studies have shown an increased prevalence of osteoarthritis within

families. Familial studies have documented an increased incidence in

first degree relatives, with 8% to 13% requiring hip replacement or

having symptoms of coxarthrosis. Twin studies further underscore the

hereditary component of osteoarthritis. Monozygotic female twins older

than 50 years of age have been shown to have an approximately 60%

heritability or genetic factor for the development of hip

osteoarthritis. Additional risk factors for the development of

osteoarthritis include increased age (older), race (whites [3% to 5%

prevalence] greater than in Asians), as well as gender. In those

younger than 50 years of age, men have a higher risk of developing hip

osteoarthritis; in those older than 50 years of age, women have a

greater incidence of the disease.

|

|

Figure 3-1 Coronal oblique view of patient with cam type femoroacetabular impingement. Note the prominence of bone anteriorly (black arrow) resulting in poor head–neck offset and reduced head/neck ratio. Note also anterior labral tear (white arrow).

|

associated with osteoarthritis of the knee, the literature linking

obesity to hip disease is less well defined. Nevertheless, a growing

body of evidence now more strongly supports the relationship of obesity

to hip osteoarthritis. This relationship seems to be important even at

a younger age; increased body mass index (BMI) earlier in life (age 18)

is a stronger predictor for the development of osteoarthritis than

increases in BMI later in life and is associated with increased risk

for requiring hip replacement. Increased BMI is also associated with

changes in gait patterns. When comparing gait patterns of nonobese and

obese persons, changes in gait symmetry, stride width, and hip

abduction angles were noted,

suggesting

that a mechanical effect in obese patients could also result in the

development of OA. Yet other studies suggest that patients who are

obese suffer more hip complaints at the same radiographic stage than

nonobese patients, therefore making them more likely to seek hip

replacement at an earlier stage than nonobese patients. Possibly

therefore, the incidence of radiographic OA is similar in obese and

nonobese populations; however, obese populations are more symptomatic

and seek treatment sooner for a given stage of osteoarthritis. In

summary, studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor in the

development of hip osteoarthritis. This association is stronger for

women, in whom increased BMI early in life has been shown to be

associated with an increased incidence of OA.

|

|

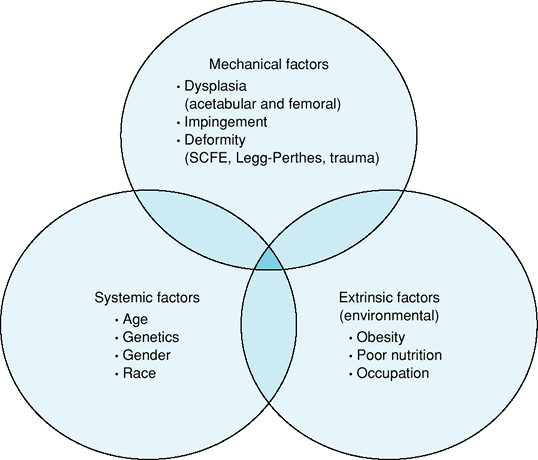

Figure 3-2 Etiologic factors associated with the development of osteoarthritis.

|

with osteoarthritis of the hip than that of the knee. However, some

population studies do suggest that occupation may have some influence

on the development of hip osteoarthritis such as the higher prevalence

of hip osteoarthritis in European farmers. Other studies have suggested

that high-demand recreational activities (professional soccer, track

and field, racket sports) may also contribute to hip arthritis. Figure 3-2 outlines various factors that contribute to the development of osteoarthritis.

times more common in women). A genetic predisposition is supported by

studies that show familial clustering and a higher prevalence in

monozygotic twins versus dizygotic twins, with monozygotes having a 3.5

greater chance of developing the disease. Further genetic

predisposition is supported by the higher prevalence in Native American

populations (5% to 6%). Seronegative arthropathies have a genetic

predisposition that is dependent on the prevalence of HLA-B27 in a

given population. Generally, the greater the prevalence of HLA-B27 in a

given population, the higher the prevalence of spondyloarthropathies.

HLA-B27 is common in certain Native American populations (up to 50%

positive), relatively common in Europeans (7% to 20%), less prevalent

in Asians and North American whites (7%), and uncommon in African

Americans (1% to 2%). Spondyloarthropathies occur in approximately 5%

to 14% of HLA-B27–positive individuals. Seronegative

spondyloarthropathies can also occur, less commonly, in individuals who

are HLA-B27–negative.

overload of the cartilage. In rare situations there is a true genetic

basis to joint destruction in which a generalized joint destruction

occurs as a result of a mutation that codes for type II collagen. Much

more commonly, the cartilage may be predisposed to damage because of

various mechanical conditions in the joint that result in a gradual

destruction of the cartilage. There is a failure of the chondrocytes to

maintain or repair damaged cartilage. Although chondrocytes are

metabolically more active in osteoarthritis, it is postulated that the

increased response is inadequate against the increased degradation of

products synthesized by the chondrocytes. Characteristic changes occur

within the cartilage structure, including changes in water content

(increased) and changes in proteoglycan concentrations (overall

decrease with shorter chains and increased chondroitin/keratin sulfate

ratio). Another characteristic change is collagen destruction:

Interleukin 1 (IL-1) from various cells (chondrocytes, synovial cells,

neutrophils)

regulates

the production of catabolic enzymes, e.g., metalloproteinases that

degrade the core protein of proteoglycans and collagenase resulting in

collagen destruction. IL-1 also influences the cartilage matrix by

causing a decreased synthesis of types II and IX collagen and an

increase in types I and III collagen.

is secondary to the inflammatory response, which begins in the

synovium. In early rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a microvascular synovial

injury appears to occur, resulting in edema and synovial cell

proliferation. Lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrate the synovium

early on, forming organized lymphoid tissue. Plasma cells are found in

more advanced disease. With synovial hyperplasia, the pannus of

synovium that extends to the edge of cartilage and bone begins to

invade and destroy the bone and cartilage. Synovial macrophages produce

cytokines (interleukin 1, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α and -β), which

in turn regulate the production of various degradative enzymes

(metalloproteinases, collagenase, stromelysin) by synovial fibroblasts

and chondrocytes, resulting in cartilage destruction. Bony erosions

result from multinucleated giant cells, which may originate from the

pannus, which is rich in macrophages. Rheumatoid synovial T cells have

been shown to produce osteoclast differentiation factor, which may be

responsible for the transformation of synovial macrophages into

multinucleated giant cells and the subsequent erosion of bone.

regardless of the cause. Occasionally, there are symptoms that may

differentiate osteoarthritis from inflammatory arthritis; however, both

may present with similar symptoms of hip pathology.

mechanical with activity-related pain or pain with certain motions

resulting from mechanical irritation or impingement. As the disease

progresses and becomes more severe, symptoms may also become more

constant and may include pain at rest.

involvement, either polyarticular or oligoarticular. It is rarely

monoarticular involving the hip. Although patients with inflammatory

disease may have hip symptoms that are mechanical in nature, these

patients tend to have a higher occurrence of constant hip pain or rest

pain because of chronic synovitis and hip joint effusion.

proximal anterior thigh (roughly 80% to 90% of patients). Pain often

radiates down the anterior thigh toward the knee. Buttock and lateral

thigh symptoms also occur in many patients, but these symptoms in

isolation are less common. The lateral proximal thigh pain is usually

felt more deeply and often more proximally (over the abductor muscles),

than symptoms of trochanteric bursitis, which are typically over the

posterolateral aspect of the greater trochanter and somewhat more

superficial. Occasionally patients present with isolated knee pain;

however, this pain tends to be more diffuse and slightly more proximal

than pain that originates from the knee.

Loss of motion, typically internal rotation, is one of the initial

findings. As the arthritis progresses, motion usually becomes more

restricted and may eventually result in a nearly ankylosed hip.

Adduction and flexion contractures typically occur. Patients may limp,

with a decreased stance phase on the affected side, and may show a

positive Duchenne sign because of pain and/or weakness. Patients with

inflammatory disease usually have less restriction in range of motion

unless the disease has caused severe erosion of the femoral head or a

significant protrusio deformity of the acetabulum resulting in a

captured femoral head.

loss is the general radiographic feature of arthritis. Specific

radiographic characteristics help differentiate osteoarthritis from

inflammatory arthritis. However, differentiation between these two

conditions occasionally can be difficult, and both may be present

radiographically.

are joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, degenerative

subchondral cysts, and peripheral osteophytes. Occasionally the joint

space may still be well maintained, but the appearance is somewhat

irregular and other features such as peripheral osteophytes or evidence

of prearthritic conditions such as femoroacetabular impingement may be

present. Initially, the joint space narrowing is often asymmetrical

with either a superomedial or superolateral wear pattern. Eventually

the entire joint space may disappear. Radiographic features are more

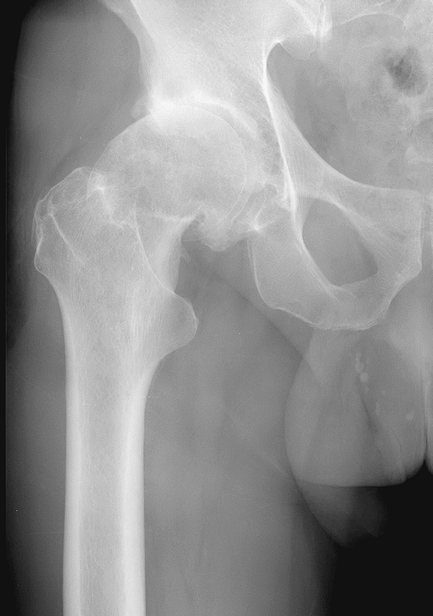

hypertrophic than those seen with inflammatory arthritis (Fig. 3-3).

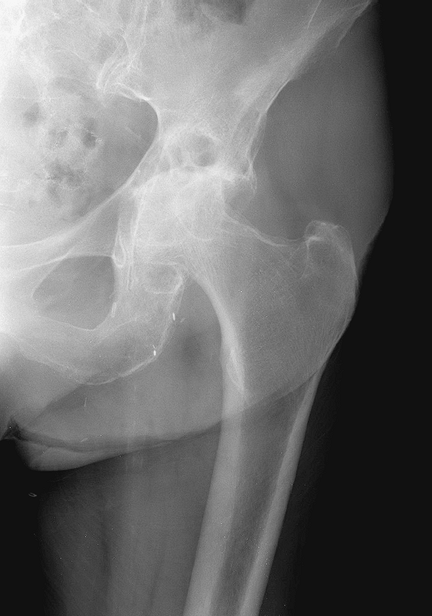

symmetrical joint space narrowing with fewer hypertrophic changes.

Peripheral osteophytes, although often visible, are usually small.

Cystic changes are more evident than with osteoarthritis. Diffuse

osteopenia is characteristic of inflammatory changes. The wear pattern

is often symmetrical at onset, but may eventually lead to a more medial

wear pattern with a protrusio deformity of the acetabulum and

superomedial migration of the femoral head (Fig. 3-4).

described. It must be remembered that approximately 40% to 50% of

patients with radiographic changes of osteoarthritis are asymptomatic.

Joint space narrowing has been shown to correlate most strongly with

clinical symptoms. A number of grading systems are presented in Table 3-2.

with hip pain is to obtain good quality, properly exposed and oriented

radiographs with the appropriate views. In a properly oriented

anteroposterior pelvis radiograph, the

obturator

foramina appear symmetrical and the coccyx projects approximately 1 cm

above the pubicsymphysis. A true lateral radiograph also should be

obtained with attention focused on the contour of the anterior femoral

head/neck junction and also the anterior acetabulum. Together with a

thorough history, the large majority of conditions can be diagnosed

with the use of plain radiographs.

|

|

Figure 3-3

Radiographic example of patient with osteoarthritis. Note the superolateral joint space narrowing, bony sclerosis, and large osteophytes. The changes are much more hypertrophic than that seen in inflammatory arthritis. |

|

|

Figure 3-4

Radiographic example of patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Note the symmetrical joint space narrowing with an early protrusio deformity, and cystic changes. Large osteophytes are not present. |

|

|

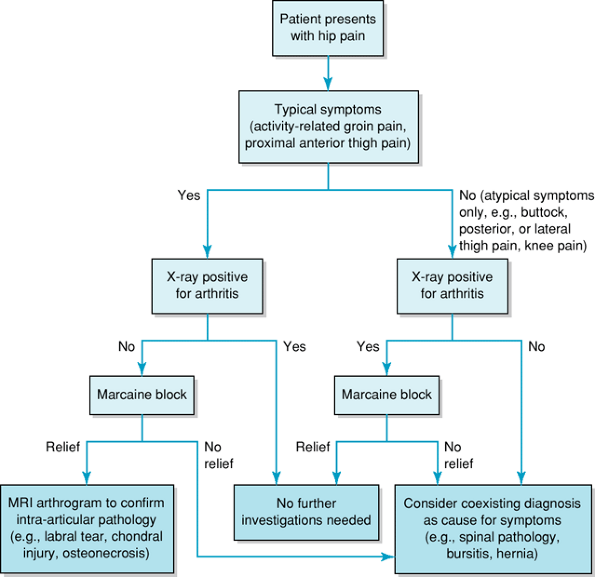

Figure 3-5 Diagnostic algorithm for patients presenting with hip pain.

|

radiographic features of arthritis. If the clinical presentation

correlates with the radiographs, then no further investigations are

necessary. Patients who present with radiographic changes of arthritis

but whose symptoms are atypical (isolated buttock, lateral hip or knee

pain) may be further evaluated with an intra-articular local anesthetic

injection placed under fluoroscopic guidance. If the symptoms are

temporarily relieved by the injection, then hip pathology is highly

likely. Patients who present with symptoms of hip pathology but whose

radiographs appear normal, despite close scrutiny for conditions such

as mild dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement, or retroverted

acetabulum, may require further investigation, usually with an MRI

scan. If intra-articular pathology such as a labral tear is suspected,

then a gadolinium arthrogram MRI is most valuable. Figure 3-5 outlines a diagnostic algorithm for patients presenting with hip pain.

total hip replacement. However, various other procedures are indicated

for certain conditions. A more detailed discussion of specific

management will be presented in subsequent chapters. For an overview,

see Table 3-3.

the usual indication for surgery. Occasionally patients complain more

of restricted function and less of pain, but it is generally the pain

that results in the restricted function and is the reason why patients

seek hip replacement surgery. Prior to surgery, patients should receive

an appropriate coarse of nonoperative management. For osteoarthritis,

this includes activity modification, weight control if feasible, the

use of walking aids, and medications (nonnarcotic analgesics and

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications). Presently, the routine use

of corticosteroid or hyaluronate hip injections cannot be recommended.

Patients with inflammatory arthritis are generally under the care of a

rheumatologist or internist for nonoperative

management. However, when considering surgery, certain considerations must be addressed; these are discussed below.

|

TABLE 3-3 Surgical Options for Patients with Osteoarthritis or Prearthritic Conditions

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||

rarely a disadvantage in delaying surgery as long as the patient is

able to maintain function. However, for conditions that may be

considered prearthritic (e.g., femoroacetabular impingement, dysplasia

without arthritic changes) there may be some merit in recommending

joint-sparing surgery when symptoms initially begin or are relatively

mild, rather than have the patient undergo a protracted coarse of

nonoperative treatment. Symptoms should still be significant enough to

justify the risks of surgery, but a long extensive coarse of

nonoperative management may be counterproductive because further

cartilage damage may occur during this time period. The goal of

nonarthroplasty joint-preservation surgery is to relieve symptoms and

if possible, also to alter the natural history and prevent or delay the

onset of arthritic changes; hence there may be an optimum window of

time in which such surgery is most successful. Unfortunately,

definitive data on altering of the natural history by

joint-preservation surgery is still lacking.

inflammatory arthritis should be counseled as to the risks, possible

complications, and usual recovery related to the procedure. Patients

should be medically stable, and any chronic medical conditions should

be assessed preoperatively and optimized prior to surgery. This

includes maintaining proper nutrition and also eliminating potential

sources of infection by specifically asking about their dental history

or any urinary problems. A careful skin evaluation is also necessary.

concerns that require consideration before surgery. These concerns

include polyarticular disease, medication used for management of

inflammatory disease, as well as unique reconstructive challenges

because of bone deformity or loss. Patients with inflammatory

arthritis, particularly rheumatoid disease, generally have

polyarticular involvement. Prior to surgery, C-spine lateral flexion

and extension views are necessary to exclude C1-C2 instability.

Additionally, in most circumstances, lower extremity surgery should be

planned prior to upper extremity surgery and hip replacement prior to

knee replacement when both are needed. It is more difficult for the

patient to regain knee motion if there is significant hip disease.

Patients with inflammatory disease are often on immunosuppressive

agents (corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs—e.g.,

methotrexate, TNF-α antagonists). The use of these before surgery

should be reduced if possible or temporarily discontinued. This is

particularly true for TNF-α antagonists, which are potent immune

suppressors; continued use during the perioperative period may increase

the risk of infection. Last, patients with rheumatoid arthritis often

have osteopenic bone, which is at increased risk of intraoperative

fracture. These patients may also have acetabular bone loss related to

a protrusio deformity, which may require bone grafting or the use of

special implants (e.g., deep profile cup or in severe cases an

acetabular reconstruction cage). As in all reconstructive cases,

appropriate surgical planning is necessary to anticipate and have

available any special implants, instruments, or bone graft that may be

required.

WH, Bourne RB, Oh I. Intra-articular acetabular labrum: a possible

etiological factor in certain cases of osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:510–514.

EW, Mandl LA, Aweh GN, et al. Total hip replacement due to

osteoarthritis: the importance of age, obesity and other modifiable

risk factors. Am J Med. 2003;114:93–98.