Miscellaneous Disorders of the Hip Joint

– HIP > Part B – Evaluation and Treatment of Hip Disorders > 7 –

Miscellaneous Disorders of the Hip Joint

hip is lengthy. This section addresses some of the unique and more

troublesome problems. Patients can present with symptoms of pain and

functional loss or may simply present with a radiographic abnormality

discovered incidentally (Table 7-1). Some of

these problems are rare and can be difficult to treat. Some disorders

have characteristic radiographic features that can be diagnostic (Table 7-1).

uncommon disorder characterized by an effusion, thickened hyperplastic

synovium with joint erosions and cysts. It can present with an

insidious onset, and the ultimate diagnosis can be difficult to make as

it may mimic other inflammatory disorders. Patients who present with a

nontraumatic monoarticular effusion should be suspected of having PVNS.

disorder is the result of a true neoplastic process or whether it is

merely a reactive monoarticular arthritis. The fact that it is

monoarticular supports the concept that it is a neoplastic disease.

Although rare, polyarticular disease can occur.

common in the third to fifth decade of life. The incidence of this

disorder is 1.5 per million; it most commonly affects the knee, hip,

ankle, hand, and foot.

is blood tinged and the synovium is thickened, nodular, and stained

reddish brown with yellow nodules. Histologically, there is a

mononuclear stromal cell infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells and

foamy histiocytes and there are areas of macrophages containing

hemosiderin.

arthritis. The classic radiographic changes that are present include

bone erosions in the head and neck of the femur and the acetabulum. The

MRI typically shows an effusion with hypertrophic synovium with areas

of low signal on T1 and bright areas on T2. Because of the hemosiderin

present, there will be other small areas of low signal intensity of T1-

and T2-weighted images.

differential diagnosis may include infection or other inflammatory

arthritis and an aspiration may be appropriate. Histologic changes from

other inflammatory arthritis disorders can often mimic PVNS,

particularly if there have been recurrent hemarthroses; thus this

condition is often overdiagnosed on pathology reports.

Attempts at radionucleotide synovectomy have been disappointing. The

surgical recurrence rate is high, especially with the diffuse form;

therefore, thorough synovectomy, curettage of the cystic lesions, and

bone grafting of cavitary defects must be meticulously performed. To

visualize the joint completely, the hip must be dislocated. Surgical

dislocation of the hip is safe, and the risk of avascular necrosis is

very low if the procedure is done correctly. I prefer a

classic

trochanteric slide osteotomy. Care is taken to avoid dissection of any

of the posterior capsular structures. The anterior hip capsule is

exposed, and an arthrotomy is made in line with the femoral neck. Flaps

are then created at the base of the neck toward the lesser trochanter

anteriorly and posteriorly along the superior aspect of the capsule

just distal to the labrum. A Z-shaped capsular arthrotomy now permits

an anterior dislocation of the hip. The ligamentum teres is avulsed or

transected, and the dislocation is complete. Adequate visualization now

permits a complete synovectomy.

|

TABLE 7-1 Radiographic Diagnoses any Orthopaedic Surgeon Should be able to Make

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

disease, moderate dose radiation therapy can be considered. Older

patients or those with associated substantial degenerative arthritis

are best managed with complete synovectomy and an arthroplasty.

Fortunately, with more choices in implant materials, such as metal on

metal or ceramic on ceramic bearing surfaces, younger patients can

enjoy the reduced recurrence rate and better function that total joint

arthroplasty can offer.

need to be followed radiographically with periodic MRI scans. A

baseline scan is done 6 weeks postsynovectomy. Asymptomatic small local

recurrences can be observed. Patient counseling is very important with

this disease, because there is risk of progressive arthritis and

subsequent need for a total hip arthroplasty. At times this can be a

frustrating, progressive, difficult-to-control disease, and patients

need to understand this at the beginning of treatment.

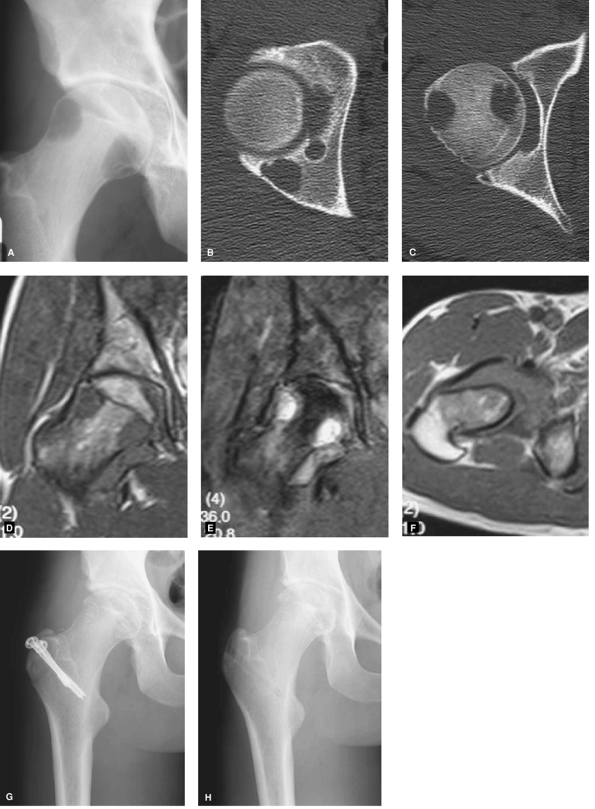

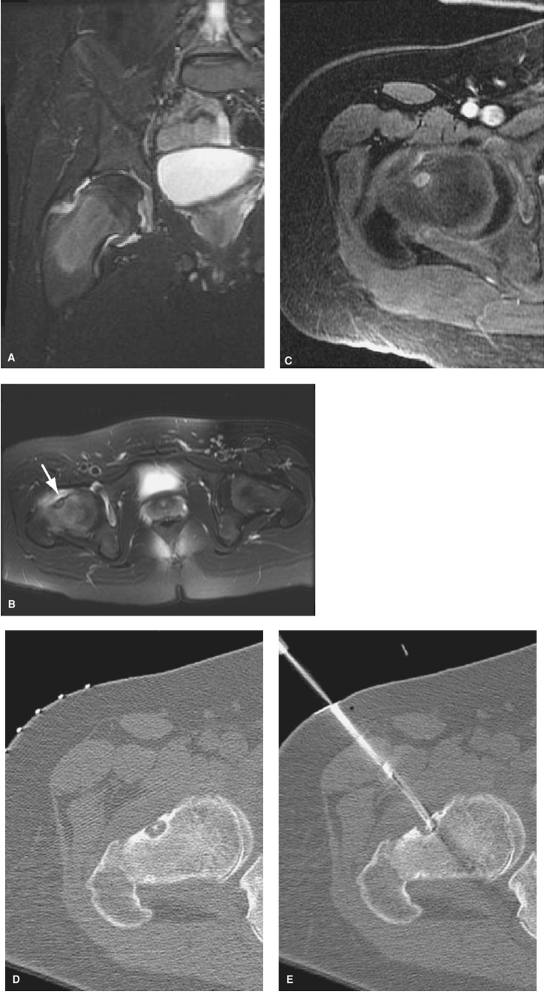

month history of increasing hip pain with episodes of severe hip pain.

His physical examination reveals a limp and a painful restricted range

of motion. His plain x-ray films and CT scan (Fig. 7-1A–C)

demonstrate subtle soft tissue swelling and multiple radiolucent

lesions affecting the femoral head and acetabulum. His MRI shows

hypointensity on T1 and increased intensity on T2 with low T1 and T2

areas consistent with hemosiderin deposits (Fig. 7-1D–F).

He was treated with an open arthrotomy with surgical dislocation of the

hip, complete synovectomy, and curettage and bone grafting of the head

and acetabular lesions (Fig. 7-1G). Nine months

later he underwent removal of the screws in the event a total hip was

ever required in the future. Currently 4 years later he remains in

remission and has maintained a normal joint space (Fig. 7-1H).

metaplastic transformation of synovial tissue. The disease can affect

any synovial tissue. The synovium becomes thickened with the formation

of nodules of cartilage. The cartilage nodules can grow and become

fixed nodules or break off and become loose bodies. Bathed in synovial

fluid, they can grow and ossify. The loose fragments can range from

tiny radiolucent pieces of cartilage to large bony masses centimeters

in diameter.

pain, limp, and restricted range of motion. Symptoms of a loose body

with locking and giving way are common. Occasionally patients present

with end-stage osteoarthritis. The disease is monoarticular affecting

the knee, shoulder, elbow, and hip most commonly. Extra-articular

disease can occur anywhere there is synovial tissue.

osteoarthritis with numerous ossified loose bodies. However, the many

loose bodies may be cartilage and unossified, and therefore not visible

on plain radiographs. In the early stages, differentiation between

other causes of an irritable hip can be difficult.

diagnostic. These can demonstrate synovial proliferation with the

presence of nodular disease and numerous loose bodies. Once calcified

and ossified, the loose bodies can be more readily seen. Occasionally a

large synovial extension into the soft tissues can result in an

impressive collection of loose bodies.

and a complete synovectomy. This can be accomplished arthroscopically

in some cases, but an open synovectomy allows a more thorough

debridement. Arthroscopy has the

advantage

of lower morbidity with less subsequent scarring. Repeat arthroscopy

also is more easily performed forrecurrent disease. If an adequate

debridement and synovectomy cannot be performed with a scope, an open

synovectomy with dislocation of the hip as described above should be

performed. This disease has a high chance of local recurrence.

|

|

Figure 7-1 A–C:

Plain radiograph and CT scan demonstrating radiolucent lesions in both the femoral head and acetabulum with a normal joint space. D–F; MRI appearance, low signal on T1, bright on T2, marked proliferative synovitis, and small areas of dark signal on both T1 and T2 from hemosiderin. G–H: Immediate postoperative and 4-year follow-up films showing cavitary lesions following curettage and grafting. |

|

|

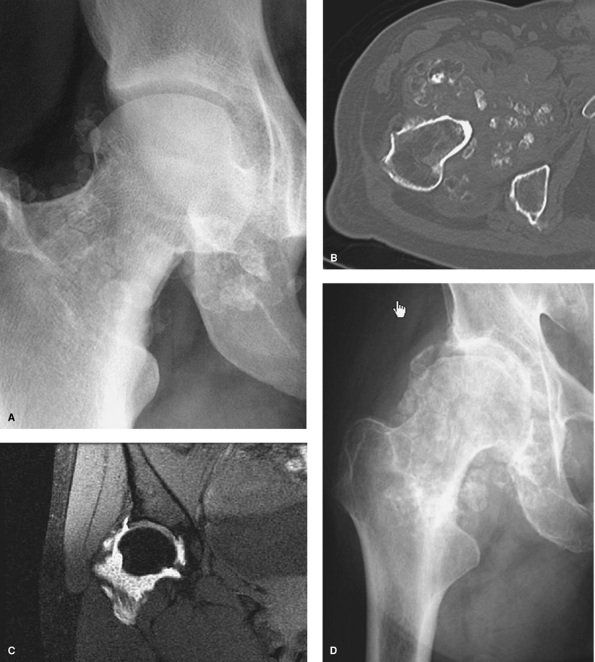

Figure 7-2 A: Plain radiograph demonstrating numerous ossified loose bodies. B: CT scan showing marked synovial proliferation and ossified loose bodies C: MRI T2-weighted image revealing numerous nonossified, noncalcified cartilaginous loose bodies. D: Progression of chondromatosis to advanced secondary degenerative arthritis 4 years later. (Photos A, B, and D courtesy of John Hunter, MD.)

|

3-year history of increasing pain, a limp and diminished range of

motion of his right hip. He has had numerous episodes of locking and

giving way of his leg, but these events were short lived and are

occurring less frequently

now.

His physical examination reveals a limp and a markedly reduced painful

range of motion. His plain radiographs, CT, and MRI scan demonstrated

minimal osteoarthritis with numerous ossified loose bodies (Fig.7-2A–C).

The radiographic features are diagnostic of synovial chondromatosis.

Four years later the patient developed progressive osteoarthritis. (Fig. 7-2D). Treatment at this stage consisted of a total hip arthroplasty with synovectomy and removal of the loose bodies.

affecting bone. It can be solitary (monostotic) or multiple

(polyostotic) and can have a wide variation in severity. It can

sometimes be associated with other medical conditions. This

developmental abnormality results in the failure of primitive bone

remodeling. The immature bone is imbedded in dysplastic fibrous tissue

and is poorly mineralized; it therefore contains the normal

constituents of bone but in a very disorganized form, resulting in

marked reduction in mechanical strength. The bone is therefore prone to

slowly developing deformities and pathologic fractures.

postfertilization somatic cell line gene mutation. The severity of the

disease is dependent on when and where the mutation occurs during

embryogenesis.

present at any age and is nonhereditary. The most common sites of

involvement are the long bones, pelvis, ribs, and craniofacial bones.

finding, pain, deformity, or fracture. The pain can be owing to the

mechanical insufficiency caused by the abnormal tissue or the lesion

itself. The degree of deformity depends on the severity and location of

the bone involved. The proximal femur is a common location, and the

mechanical weakness can result in severe angular deformities with

limb-length inequality. This is especially so in polyostotic fibrous

dysplasia as it tends to progress in adult life. The classic deformity

of the proximal femur is the so-called “shepherd’s crook” deformity, a

pronounced varus deformity with bowing of the femur and shortening of

the limb.

radiograph is usually diagnostic, and the x-ray film characteristics

are so distinctive that a diagnosis can be made with confidence. The

lesion is usually well demarcated and consists of fairly homogenous

fibro-osseous calcified material that has a ground-glass appearance.

Occasionally the plain radiographs can be nonspecific owing to cystic

degeneration, multiple fractures, or deformity. Patients with a

nonspecific radiographic appearance require further investigation and

sometimes a biopsy.

view of the bone, and a diagnosis can often be made at this point. If

the radiographic appearance is atypical, an MRI study and a biopsy may

be needed.

T1-weighted image and a T2 signal of higher intensity. The signal

intensity is determined by the relative composition of fibrous tissue

and mineralized immature bone. There may also be areas of cystic

degeneration with a high T2 signal.

is not a neoplastic condition but rather to deal with the mechanical

consequences of a relatively weak and deformed bone. Treatment of the

deformed bone is difficult because of its poor mechanical strength, and

eradication of the fibrous dysplasia usually is not possible.

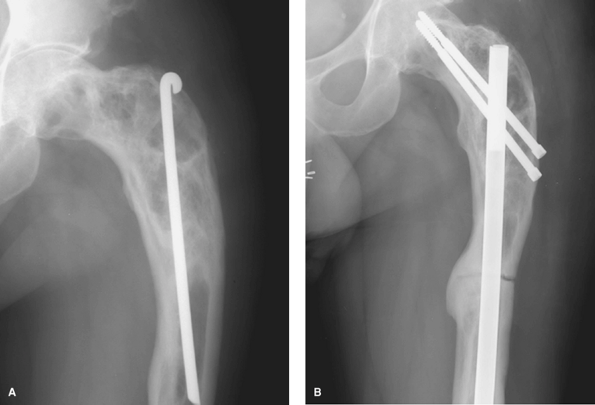

increasing activity-related pain affecting the right groin and thigh.

She has mild pain at rest and moderate pain at night. Her physical

examination is essentially normal. Her CT scan shows a lesion in the

femoral neck, largely radiolucent with a deficiency in the medial

aspect of the cortex (Fig. 7-3A). There is a

well-defined reactive rim with increased bone density. The radiographic

differential is large, favors a benign process, and includes

nonossifying fibroma, fibrous dysplasia, unicameral bone cyst, and

eosinophilic granuloma, and so on. Owing to her symptoms, the location

of the lesion, and the cortical defect, the patient underwent an open

biopsy via a transtrochanteric window under fluoroscopic guidance.

Frozen section was consistent with fibrous dysplasia. The lesion was

then curetted, and a fibular strut graft was passed up through the neck

along the medial cortex of the neck (Fig. 7-3B).

A cortical fibular allograft strut was selected for the reconstruction

to reduce the risk of dysplastic bone remodeling of the graft. Her

follow-up radiograph 4 years later demonstrated a healed graft without

replacement by fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 7-3C).

|

|

Figure 7-3 A:

Coronal CT scan demonstrating relatively nonspecific lesion with a pronounced rim of reactive bone surrounding a radiolucent lesion with a defect in the femoral neck. B: Intraoperative image following biopsy and curettage of fibrous dysplasia with insertion of an allograft fibular strut. C: Four-year follow-up radiograph showing healing of the graft and no evidence of graft erosion by fibrous dysplasia. |

|

|

Figure 7-4 A:

Plain radiograph of previously treated fibrous dysplasias. Some areas of radiolucency with a ground glass appearance. Previous Rush rod and surgical changes. Note the varus deformity. B: Follow-up radiograph 2 years following corrective osteotomy and reconstruction nail fixation. |

episodes of his right hip and thigh pain. He has had episodes of severe

pain sometimes requiring crutches. As a child he underwent a surgical

procedure because of recurrent pain. His physical examination revealed

a 1.5-cm. limb-length discrepancy with shortening in the femur. He had

a nearly full range of motion of his hip with minimal pain at the

extremes. His radiographs demonstrate mild osteoarthritis, a varus

deformity of the femoral neck and proximal femur, evidence of previous

surgery, and a mixed radiolucent/radiodense lesion. On close

inspection, the bone has a ground-glass appearance (Fig. 7-4A.)His

previous surgical records included a pathology report describing

fibrous dysplasia. Given his symptoms and the varus deformity, a

corrective osteotomy with intramedullary fixation was performed (Fig. 7-4B). The patient has since enjoyed a marked reduction in his symptoms.

proximal femur and acetabulum. The role of the orthopaedic surgeon in

the management of a patient with metastatic disease is to establish the

diagnosis, identify those patients at risk for fracture, and

reconstruct bone defects following fracture (Table 7-2).

different compared with a traumatic fracture in normal bone. Every

effort must be directed to the restoration of the patient’s function

and relief of pain as quickly as possible. Fixation choices should

include those options that permit immediate full weight bearing, with

the assumption that the fracture itself will never heal. The surgeon

must recognize that further local progression of the metastatic lesion

may occur.

retention of the femoral head. Curettage, cementation, and screw

fixation of femoral neck lesions is rarely performed. Reduction and

fixation of femoral neck fractures should not be performed. These

lesions are best managed with either a total hip arthroplasty or

hemiarthroplasty. Consideration should be given to using a long

cemented stem. This permits predictable immediate fixation, allows for

postoperative radiation therapy, and extends the scope of the

reconstruction to prophylactically strengthen the remaining femur. The

management of an impending femoral neck fracture is the same as for a

completed fracture. However, palliative radiotherapy may be offered

first as some patients may have a very good response and thus avoid

surgery.

|

TABLE 7-2 Metastatic Bone Disease Basic Surgical Principles

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

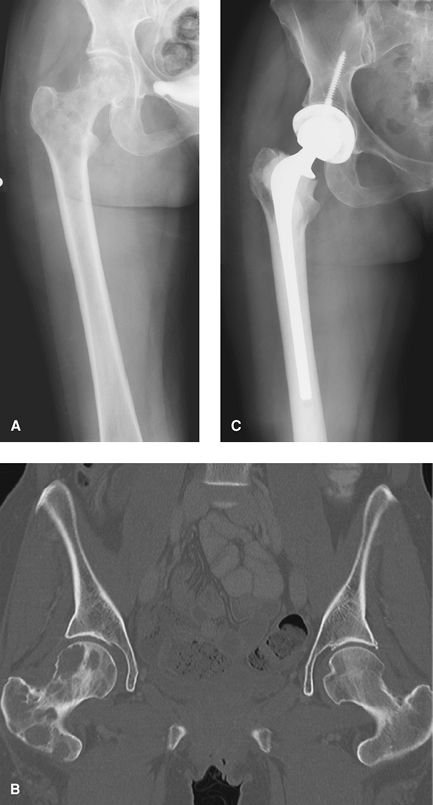

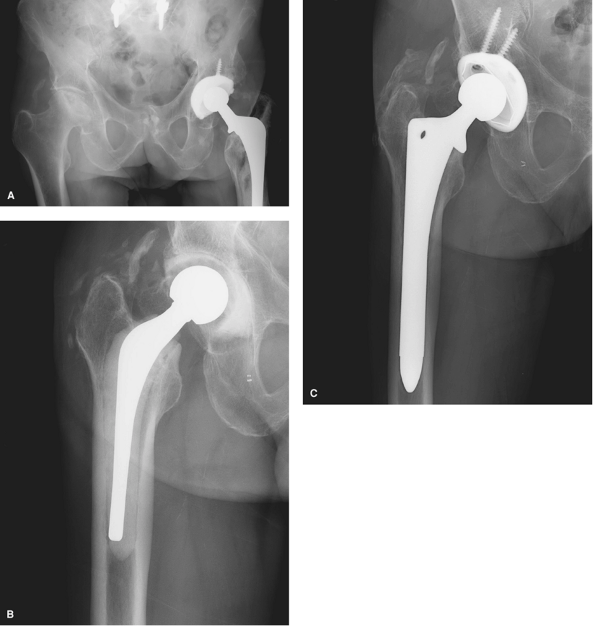

breast cancer. She has had increasing right hip pain for the past

month. The pain was initially present only with weight bearing, but it

is now present at rest and she is using crutches and a wheelchair. She

has had radiation therapy to that area 4 weeks ago. Her physical exam

demonstrated an otherwise healthy-appearing female, but her hip

examination revealed a painful range of motion. Her plain radiographs

and CT scan show widespread disease affecting the head, neck, and

proximal femur. The patient has failed radiation therapy and is at risk

of fracture. The intent of treatment is to fix the problem predictably,

permit immediate return to function, and avoid future problems related

to progression of the disease. Consequently, an arthroplasty was

chosen. In this case, a total hip arthroplasty was performed; a

hemiarthroplasty would work as well, but a total hip avoids the

possibility of a painful hemiarthroplasty in a young patient. A long

cemented stem was chosen to permit predictable immediate fixation,

antibiotic delivery, and prophylactic stabilization of as much of the

femur as possible (Fig. 7-5A–C).

characteristic presentation. The lesion is typically ≤1 cm in diameter.

It is characterized by a radiolucent nidus with surrounding reactive

bone formation. The diagnosis is easy to make histologically.

children and young adults, with a male predilection of two to one; it

can occur in any bone. The lesion produces prostaglandins, which

mediate pain and produce new bone formation. Aspirin and other

anti-inflammatories block the production of prostaglandin, hence

controlling the symptoms.

throbbing pain, typically worse at night. The pain is particularly

responsive to aspirin, something patients often stumble on by

themselves. Patients may medicate themselves to the

point

of developing tinnitus. If the tumor is present in the neck or head of

the femur, it can present with typical pain as well as an irritable hip.

|

|

Figure 7-5 A: Multiple radiolucent destructive lesions affecting the femoral head and neck B: CT scan demonstrating diffuse disease from metastatic breast carcinoma C: Pose operative radiograph, long stemmed cemented total hip arthroplasty.

|

classically demonstrating a radiolucent nidus with a surrounding area

of reactive bone produced by prostaglandin production. Technetium bone

scanning typically shows a hot spot. A bone scan is helpful when the

lesion is not readily apparent on plain radiographs. Computed

tomography is often diagnostic and is helpful in locating the lesion in

difficult anatomic locations. Dynamic enhanced (gadolinium angiography)

magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in differentiating an osteoid

osteoma from other similar-appearing lesions. The nidus of an osteoid

osteoma will show a bright blush from the gadolinium.

dramatic appearance on magnetic imaging with edema involving the bone

and surrounding soft tissues. A prominent and florid synovial reaction

can occur if the lesion is intra-articular, on the surface of the

femoral neck, or near the synovium. This can mimic other synovial

proliferative disorders both clinically and radiographically.

is not acceptable is radiofrequency ablation. With the precise guidance

of computed tomographic fluoroscopy under general anaesthesia, a

radiofrequency needle is placed within the center of the nidus and

heated to 90°C for 6 minutes. The morbidity is low, the failure rate is

low, and typically the patient is painfree the next day. A biopsy is

done at the time of needle insertion, but because of the small size of

the needle used, representative tissue is seen only 40% of the time.

More than 95% of patients can be expected to be cured with a single

treatment. The risk of relapse is low. The patient may resume full

unrestricted activity immediately following treatment.

of intermittent hip pain. It has been increasing over the last 2 months

and is particularly worse at night. The patient has been taking

ibuprofen with moderate pain relief. Physical examination reveals a

marked restriction in range of motion of the hip and muscular atrophy.

MR imaging reveals a lesion on the neck of the femur with an effusion,

synovitis, and surrounding edema (Fig. 7-6A).

The image was initially suggestive of either infection or Ewing

sarcoma. The clinical and radiographic features were more consistent

with osteoid osteoma with a brisk inflammatory reactive response (Fig. 7-6B–D). The patient was treated with a CT-guided radiofrequency thermal ablation (Fig. 7-6E). The patient had an excellent response and remains symptomfree 2 years later.

that classically arises in the epiphysis and accounts for <1% of all

primary bone tumors. Most tumors arise in patients with active

epiphyses, and the most common location is the proximal humerus,

followed by the knee and hip.

an incidental finding. Symptoms include pain, swelling, and a painful

range of motion.

defined reactive rim. The lesion may show subtle areas of calcification

within it, and its location is usually indicative of the diagnosis. The

lesion is hot on bone scan, and generalized uptake around the affected

joint is not uncommon.

|

|

Figure 7-6 A: T2-weighted MR image demonstrating marrow signal changes in the proximal femur with a large effusion. B: Axial MR image demonstrating the nidus. C: Dynamic enhanced MRI showing characteristic blush from gadolinium. D–E: CT images demonstrating the nidus and placement of the radiofrequency probe.

|

intralesional calcification and better defines the plain radiographic

appearance. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a homogenous

hypointense appearance on T1-weighted imaging and variable to

hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images. A secondary aneurysmal bone

cyst component is not uncommon with chondroblastoma. This is evident by

an area of high signal on T2 suggestive of blood and fluid levels on

both MRI and CT scans. A large amount of reactive edema in the bone and

synovitis in the joint is often seen as well and explains the symptoms

of pain and joint irritability seen with often relatively small

lesions. Giant cell tumor and clear cell chondrosarcoma are in the

differential, but these tend to occur in older patients. Clear cell

chondrosarcoma can have a similar MRI appearance to chondroblastoma but

is usually in an older age group, is larger, and extends beyond the

epiphysis.

recurrence rate of 5% to 15%, largely depending on the thoroughness of

resection. Chondroblastoma of the femoral head presents a challenge in

all aspects of its management. In patients in whom the diagnosis is

unlikely to be a clear cell chondrosarcoma, treatment can consist of

open biopsy, frozen section, and immediate curettage and bone grafting.

The surgical approach can include arthrotomy, surgical dislocation, and

approaching the lesion from a window in the neck below the articular

cartilage or a transtrochanteric tunnel through the neck of the femur.

Open arthrotomy has a higher morbidity but would most likely allow for

a more complete curettage. A transtrochanteric approach has a lower

morbidity but a higher chance of local recurrence. The older patient

with a radiolucent epiphyseal tumor is a more difficult problem. The

differential diagnosis would include a clear cell chondrosarcoma. A

biopsy has the potential to contaminate either the joint or the

intertrochanteric region depending on the approach. If the index of

suspicion is very high or if the femoral head is so involved and the

joint is not contaminated, an excisional biopsy and total hip

arthroplasty can be considered on very rare occasions.

presents with a 4-month history of left hip pain. Activity related, it

is increasing in severity and is present at rest and at night. Physical

examination reveals a limp and a generally diminished range of motion

of her hip with severe pain at the extreme of motion. Plain radiographs

demonstrate a radiolucent lesion arising solely in the epiphysis of the

proximal femur (Fig. 7-7A). MRI demonstrates a well-defined lesion with a modest amount of edema (Fig. 7-7B, C).

The clinical and radiographic features strongly favored a

chondroblastoma. The patient was treated by an intralesional curettage

and bone grafting. This was done via a transtrochanteric approach with

fluoroscopic guidance. A core of bone was removed with a 16-mm

trephine. The bone was reserved, and the curettage was guided by

fluoroscopy with direct visualization using a laparoscope through the

tunnel. Once completed, the core was reinserted into the defect and the

lateral deficiency was grafted with morselized allograft. The

postoperative MRI at 18 months shows the transtrochanteric approach and

the resolution of the lesion with healing of the graft. (Fig. 7-7D–E).

Occasionally, severe joint destruction can occur, most often when the

diagnosis is delayed. This problem usually is managed with a resection

arthroplasty and a delayed total hip arthroplasty.

States. The incidence is increased in immunocompromised and elderly

patients with comorbidities. Forty-five percent of patients are older

than 65 years of age. The morbidity and mortality rate is dependent on

the organism.

|

|

Figure 7-7 A: Plain radiograph showing a subtle radiolucent epiphyseal lesion. B–C: MR image demonstrating marrow edema involving the head and neck. D:

Two-year postoperative MRI. The track made by the trephine to obtain access to the lesion is seen on this image. The bone graft is evident in the cavity. E: The corresponding plain radiograph showing the grafted lesion. |

subtle joint irritability to fulminant systemic sepsis. Typically, the

presentation is monarticular and is usually acute in onset. Patients

with pre-existing joint disease report a sudden increase in their joint

symptoms.

and external rotation and any motion of the joint is extremely painful.

With severely immunocompromised patients, the signs may be less

obvious, and in patients with severe sepsis, the diagnosis of

polyarticular sepsis may be difficult to make. Ninety percent of cases

are monarticular.

helpful in demonstrating an effusion with reactive edema. Patients with

pre-existing hip pathology can present more of a challenge

radiographically, as the underlying arthritic problem can be the source

of pain.

|

|

Figure 7-8 A: Plain radiograph showing advanced avascular necrosis and soft tissue swelling around the right hip joint. B: Interval antibiotic spacer prosthesis. The patient was allowed full weight bearing on this device. C: Subsequent definitive reconstruction with a cementless implant.

|

analysis is the test of choice. Treatment is based on the clinical

findings and the preliminary joint fluid analysis. If the suspected

diagnosis is sepsis, the treatment is arthrotomy, debridement, and

antibiotic therapy.

anterolateral approach, excision of the anterior capsule of the hip,

and a synovectomy without dislocating the hip. In patients who have

pre-existing end-stage hip disease or those patients with persistent

infection with a destroyed hip joint, I resect the femoral head and

insert a primary functionalantibiotic-impregnated spacer total hip

prosthesis. Various spacers are now available. I prefer to use a

therapeutic dosage of antibiotics in the bone cement, typically 4.8 g

of gentamicin and 2.0 g of vancomycin per 40-g package of cement. The

patient receives 6 weeks of parenteral antibiotics followed by a

definitive arthroplasty, usually a minimum of 8 weeks later. The second

stage can be deferred indefinitely in patients who are elderly and

frail and have other significant comorbidities.

of a low-grade gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma and has been receiving

chemotherapy. He has had right hip pain for the past 5 months. It began

suddenly and has been getting worse. Over the past 3 days the pain has

become severe, and he has been unable to get out of bed for the past 24

hours. On physical examination he appears unwell and his temperature

was 39.5°C. His hip is extremely painful to any motion, and he has

marked tenderness in his right groin. His hip was aspirated, revealing

a white count of 65,000 cells with 80% nucleated polymorphonuclear

cells. A Gram stain revealed Gram-positive cocci. His plain radiograph

showed stage four avascular necroses (Fig. 7-8A).

The patient was treated with surgical debridement and a two-stage total

hip replacement, first using a functional antibiotic-impregnated spacer

prosthesis (Fig. 7-8B). He was treated with 6

weeks of intravenous vancomycin and oral rifampin for

methicillin-resistant staph aureus. He continued his chemotherapy, and

initially it was planned to leave the temporary device in indefinitely.

He did well with his lymphoma, was allowed to be as active as possible,

and finally a year later his hip was replaced with a definitive

prosthesis (Fig. 7-8C).

R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, et al. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip: a

technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without

the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1119–1124.

BA, Duncan CP, Beauchamp CP. Long-term elution of antibiotics from

bone-cement: an in vivo study using the prosthesis of antibiotic-loaded

acrylic cement (PROSTALAC) system. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(3):331–338.