The Ankle and Foot

usually are straightforward; the bones and joints that are explored

commonly are superficial, if not subcutaneous. Apart from technical

problems associated with the surgery itself, the most common

complication in foot and ankle surgery is poor wound healing. For this

reason, it is important to evaluate both the circulation and the

sensation of the foot. Ischemic or neuropathic feet heal poorly and are

a frequent contraindication to elective surgery. In patients with

diabetes, ischemia and neuropathy may coexist; all feet of such

patients must be evaluated carefully before any foot surgery is

undertaken. Smoking is also a relative contraindication to surgery,

especially in cases of open reduction and internal fixation for

fractures of the calcaneus.

skin flaps that are cut; it is important to cut these flaps as thickly

as possible and to avoid forceful retraction. Longer incisions require

less forceful retraction to achieve identical exposure. As a result,

they often are safer than are short incisions. (Remember that skin

incisions heal from side to side and not from end to end.)

describes approaches to the ankle and the hindpart of the foot, because

most provide access to both areas. The anterior approach to the ankle is used for arthrodesis; it offers excellent exposure of the anterior compartment of the ankle joint. The approach to the medial malleolus is a commonly used incision, providing access to the distal tibia in cases of fracture. A more extensive approach to the medial side of the ankle joint also exposes the distal tibia, but involves an osteotomy. The posteromedial approach to the ankle

exposes the soft tissues of the area. It is used frequently for

soft-tissue operations, including the surgical correction of clubfoot.

The posterolateral approach to the ankle joint provides limited access to the back of the joint and the posterior facet of the subtalar joint. The lateral approach to the ankle and hindpart of the foot exposes the ankle and the joints of the hindfoot. The lateral approach to the hindpart of the foot and the posterolateral approach to the talocalcaneal joint

are used for surgery on the joints of the posterior part of the foot.

The lateral approach to the calcaneus exposes the lateral aspect of the

calcaneus, the calcaneocuboid, and subtalar joints. It is mainly used

for open reduction and internal fixation of the os calcis.

to the midportion of the foot, the tarsometatarsal and midtarsal joints

and those muscles that attach to them. Surgery in this area is

relatively uncommon in general orthopaedic practice; it usually is

associated with specific operative procedures designed for single

pathologic states. Because these structures are very superficial, the

approaches are dealt with mainly pictorially.

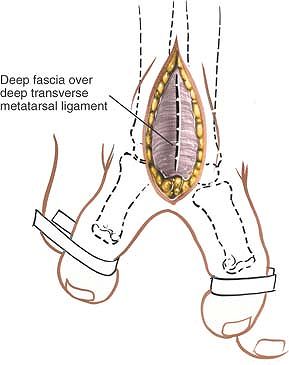

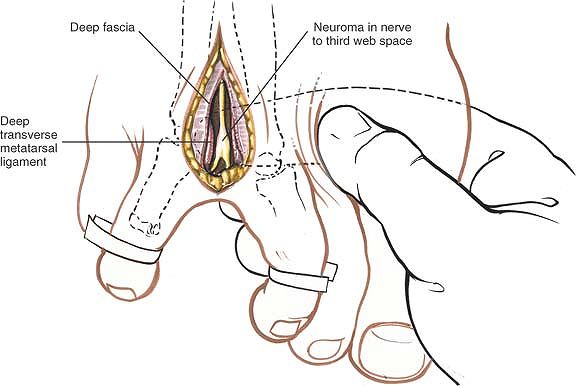

can be used for the treatment of several conditions, including Morton’s

neuroma. The latter approach also can be used to reach the

metatarsophalangeal joint.

after this group of approaches. The first section deals with the

applied anatomy of the approaches, that is, the applied anatomy of the

dorsum of the foot. The second section, an account of the anatomy of

the sole of the foot, should provide an understanding of those

structures that may be damaged in severe foot trauma or infection.

The decision to use this approach rather than the lateral transfibular

approach, the medial transmalleolar approach, or the posterior approach

depends on the condition of the skin and the surgical technique to be

used. Its other uses include the following:

-

Drainage of infections in the ankle joint

-

Removal of loose bodies

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of comminuted distal tibial fractures (pilon fractures)

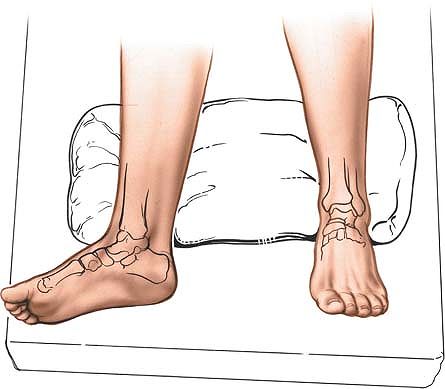

Partially exsanguinate the foot either by elevating it for 3 to 5

minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage loosely to the foot and

binding it firmly to the calf. Then, inflate a thigh tourniquet.

Partial

exsanguination

allows the neurovascular bundle to be identified, because the venous

structures will appear blue. Some continuous vascular oozing must be

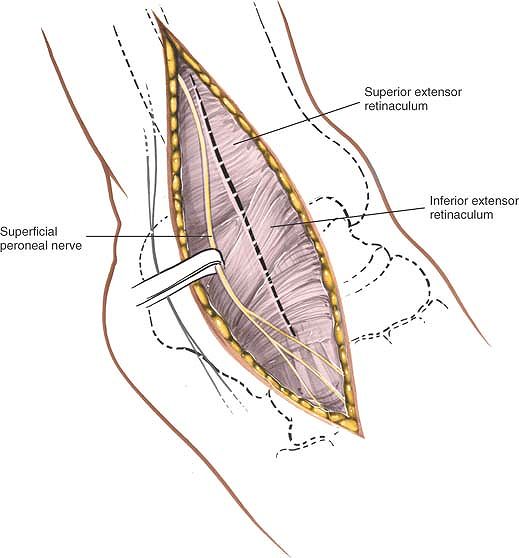

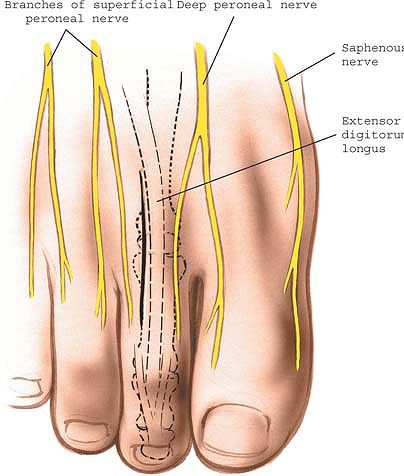

expected, however (Fig. 12-1).

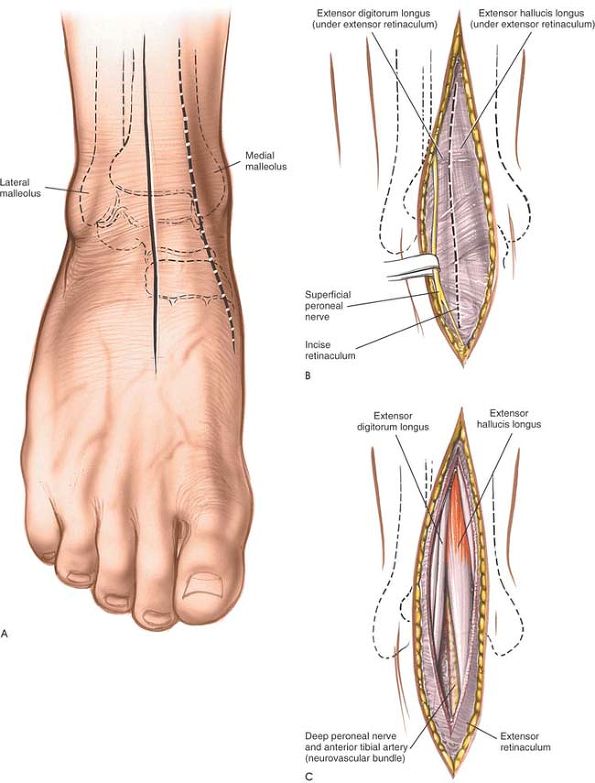

aspect of the ankle joint. Begin about 10 cm proximal to the joint, and

extend the incision so that it crosses the joint about midway between

the malleoli, ending on the dorsum of the foot. Take great care to cut

only the skin; the anterior neurovascular bundle and branches of the

superficial peroneal nerve cross the ankle joint very close to the line

of the skin incision (Fig. 12-2A). Alternatively, make a 15-cm longitudinal incision with its center overlying the anterior aspect of the medial malleolus (see Fig. 12-2).

muscles define a clear intermuscular plane. Both muscles are supplied

by the deep peroneal nerve, but the plane may be used because both

receive their nerve supplies well proximal to the level of the

dissection. The plane must be used with great caution, however, because

it contains the neurovascular bundle distal to the ankle (see Figs. 12-58 and 12-59).

|

|

Figure 12-1 Position for the anterior approach to the ankle.

|

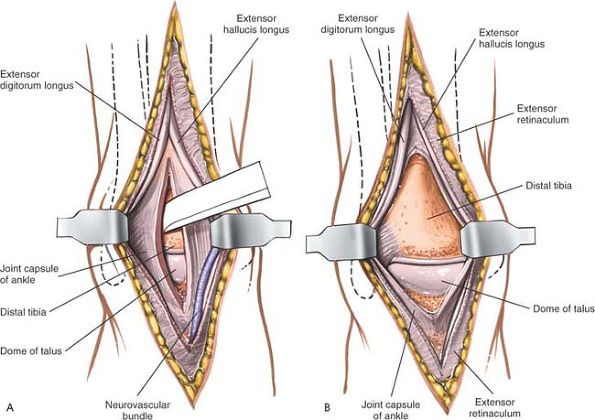

Find the plane between the extensor hallucis longus and extensor

digitorum longus muscles a few centimeters above the ankle joint, and

identify the neurovascular bundle (the anterior tibial artery and the

deep peroneal nerve) just medial to the tendon of the extensor hallucis

longus (see Fig. 12-2C).

Trace the bundle distally until it crosses the front of the ankle joint

behind the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus. Retract the tendon

of the extensor hallucis longus medially, together with the

neurovascular bundle. Retract the tendon of the extensor digitorum

longus laterally. The tendons become mobile after the retinaculum has

been cut, but the neurovascular bundle adheres to the underlying

tissues and requires mobilization (Fig. 12-3A).

the tibia together with the anteromedial ankle joint capsule.

|

|

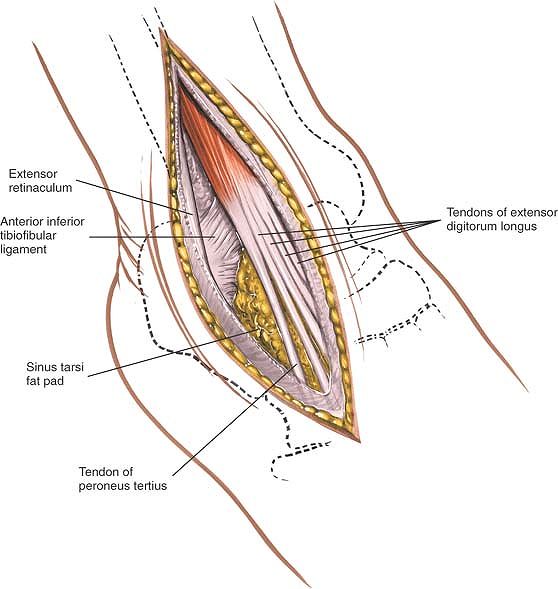

Figure 12-2 (A) Make a longitudinal incision over the anterior aspect of the ankle joint. (B) Identify and protect the superficial peroneal nerve. Incise the extensor retinaculum in line with the skin incision. (C)

Identify the plane between the extensor hallucis longus and the extensor digitorum longus, and note the neurovascular bundle between them. |

|

|

Figure 12-3 (A)

Retract the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus medially with the neurovascular bundle. Retract the tendon of the extensor digitorum longus laterally. Incise the joint capsule longitudinally. (B) Retract the joint capsule to expose the ankle joint. |

|

|

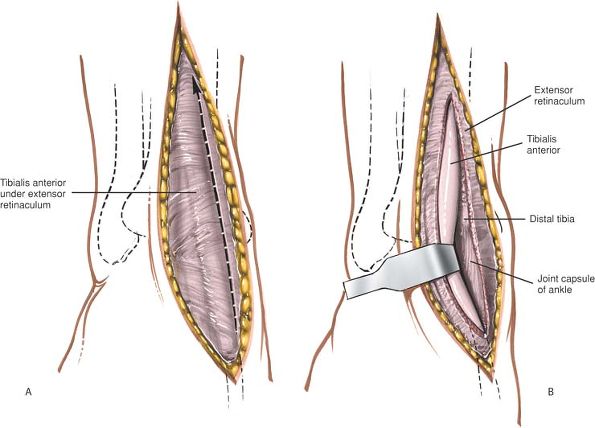

Figure 12-4 (A) Alternately, incise the extensor retinaculum on the medial side of the tibialis anterior tendon. (B) Retract the tibialis anterior laterally to expose the anterior surface of the ankle joint.

|

tissues longitudinally to expose the anterior surface of the distal

tibia. Continue incising down to the ankle joint, then cut through its

anterior capsule. Expose the full width of the ankle joint by detaching

the anterior ankle capsule from the tibia or the talus by sharp

dissection (see Fig. 12-3). Some periosteal

stripping of the distal tibia may be required. Although the periosteal

layer usually is thick and easy to define, the plane may be obliterated

in cases of infection; the periosteum then must be detached piecemeal

by sharp dissection.

care to preserve as much soft-tissue attachments to bone as possible.

Meticulous preoperative planning will allow smaller, precise incisions

with consequent reduction in soft-tissue damage.

(the anterior neurovascular bundle) must be identified and preserved

during superficial surgical dissection. They are in greatest danger

during the skin incision, because they are superficial and run close to

the incision itself (see Figs. 12-58 and 12-59).

Above the ankle joint, the neurovascular bundle lies between the

tendons of the extensor hallucis longus and tibialis anterior muscles

at the joint; the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus crosses the

bundle. The plane between the tibialis anterior and the extensor

hallucis longus can be used as long as the neurovascular bundle is

identified and mobilized so as to preserve it (see Fig. 12-59).

internervous plane, on occasion it can be extended proximally to expose

the structures in the anterior compartment. To expose the proximal

tibia, use the plane between the tibia and the tibialis anterior muscle

(see Fig. 12-4). Distal extension to the dorsum of the foot is possible, but rarely, if ever, required (see Fig. 12-59).

for open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the medial

malleolus.2 The approaches provide excellent visualization of the malleolus.

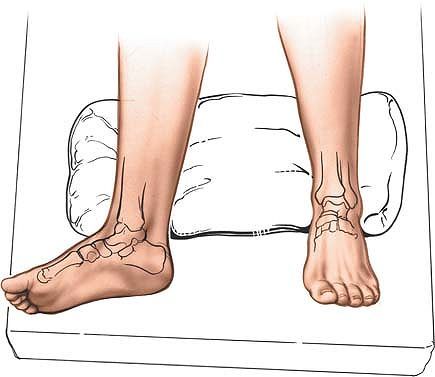

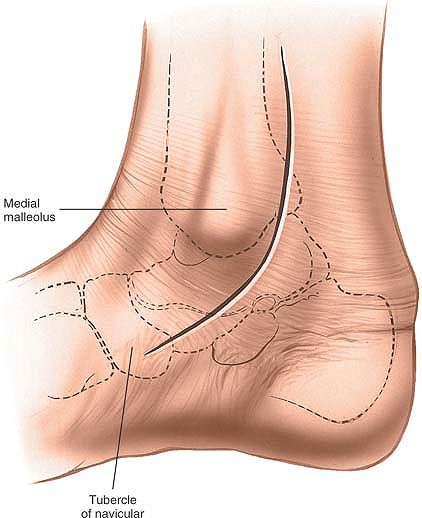

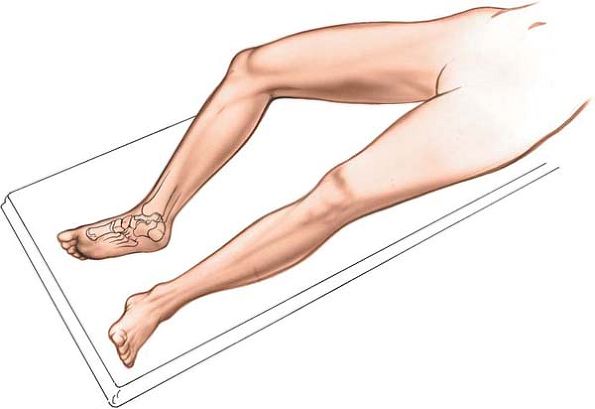

natural position of the leg (slight external rotation) exposes the

medial malleolus well. Exsanguinate the limb by elevating it for 3 to 5

minutes, then inflate a tourniquet. Standing or sitting at the foot of

the table makes it easier to angle drills correctly (Fig. 12-5).

-

The anterior incision

offers an excellent view of medial malleolar fractures. It also permits

inspection of the anteromedial ankle joint and the anteromedial part of

the dome of the talus. Figure 12-5

Figure 12-5

Position for the approach to the medial malleolus. The leg falls

naturally into a few degrees of external rotation to expose the

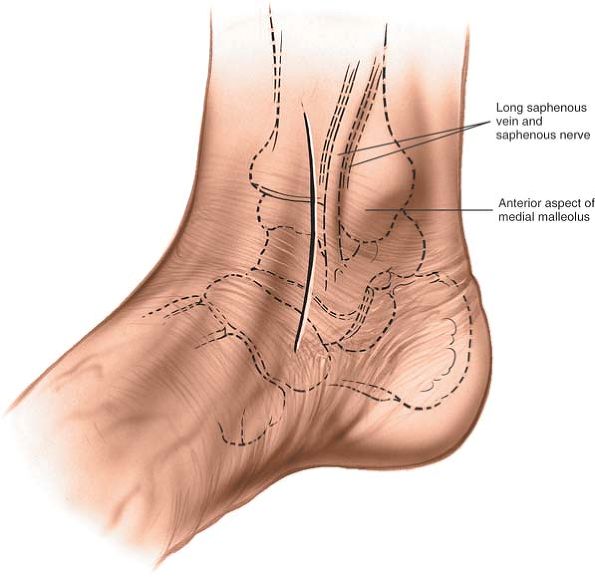

malleolus.Make a 10-cm longitudinal curved incision on the medial

aspect of the ankle, with its midpoint just anterior to the tip of the

medial malleolus. Begin proximally, 5 cm above the malleolus and over

the middle of the subcutaneous surface of the tibia. Then, cross the

anterior third of the medial malleolus, and curve the incision forward

to end some 5 cm anterior and distal to the malleolus. The incision

should not cross the most prominent portion of the malleolus (Fig. 12-6). -

The posterior incision allows reduction and fixation of medial malleolar fractures and visualization of the posterior margin of the tibia.Make a 10-cm incision on the medial side of the ankle.

Begin 5 cm above the ankle on the posterior border of the tibia, and

curve the incision downward, following the posterior border of the

P.630

medial malleolus. Curve the incision forward below the medial malleolus to end 5 cm distal to the malleolus (see Fig. 12-10).

|

|

Figure 12-6 Keep the incision just anterior to the tip of the medial malleolus.

|

the approach is safe because the incision cuts down onto subcutaneous

bone.

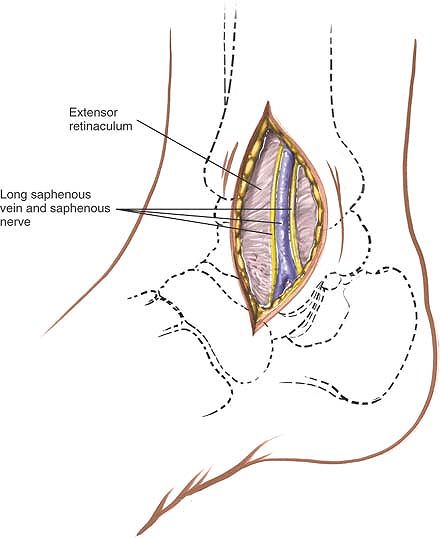

and preserve the long saphenous vein, which lies just anterior to the

medial malleolus. Accurately locating the skin incision will make it

unnecessary to mobilize the skin flaps extensively. Next to the vein

runs the saphenous nerve, two branches of which are bound to the vein.

Take care not to damage the nerve; damage leads to the formation of a

neuroma. Because the nerve is small and not easily identified, the best

way to preserve it is to preserve the long saphenous vein, a structure

that on its own is of little functional significance (Fig. 12-7).

the bone fragment as possible to preserve its blood supply.

|

|

Figure 12-7 Widen the skin flaps. Identify the long saphenous vein and the accompanying saphenous nerve.

|

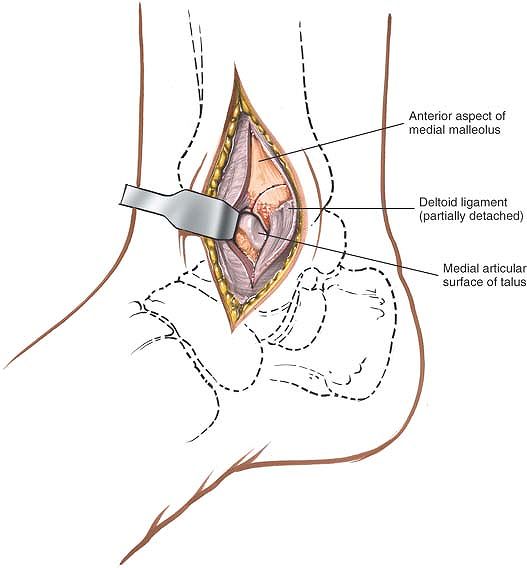

longitudinally to expose the fracture site. Make a small incision in

the anterior capsule of the ankle joint so that the joint surfaces can

be seen after the fracture is reduced (Fig. 12-8).

This is especially important in vertical fractures of the medial

malleolus where impaction at the joint surface frequently occurs. The

superficial fibers of the deltoid ligament run anteriorly and distally

downward from the medial malleolus; split them so that wires or screws

used in internal fixation can be anchored solidly on bone, with the

heads of the screws covered by soft tissue (Fig. 12-9; see Fig. 12-56).

Take care not to cut the tendon of the tibialis posterior muscle, which

runs immediately behind the medial malleolus; the incision into the

retinaculum permits anterior retraction of the tibialis posterior

tendon. Continue the dissection around the back of the malleolus,

retracting the other structures that pass behind the medial malleolus

posteriorly to reach the posterior margin (or posterior malleolus) of

the tibia. The exposure allows reduction of some fractures of that part

of the bone.

visualization of most fractures using appropriate reduction forceps,

the angle of the approach is such that the displaced fragments cannot

be fixed internally from this approach. Separate anterior approaches

are required to lag any posterior fragments back. It always is

advisable to obtain an intraoperative radiograph showing the displaced

fragment fixed temporarily with a K-wire before definitive fixation is

inserted. Reduction of these fragments is difficult because of limited

exposure, and inaccurate reduction may occur. To improve the view of

the posterior malleolus, externally rotate the leg still further (Fig. 12-12; see Figs. 12-55 and 12-56).

|

|

Figure 12-8 Make a small incision in the anterior capsule of the ankle joint to see the articulating surface.

|

|

|

Figure 12-9 Split fibers of the deltoid ligament to allow for internal fixation of the fractured malleolus.

|

|

|

Figure 12-10 The posterior incision for the approach to the medial malleolus follows the posterior border of the medial malleolus.

|

|

|

Figure 12-11 Retract the skin flaps and begin to incise the retinaculum behind the medial malleolus.

|

|

|

Figure 12-12

Anteriorly retract the tibialis posterior. Free up and retract the remaining structures around the back of the malleolus posteriorly to expose the posterior aspect of the medial malleolus. |

may form a neuroma and cause numbness over the medial side of the

dorsum of the foot. Preserve the nerve by preserving the long saphenous

vein.

at risk when the anterior skin flaps are mobilized. Preserve it if

possible, so that it can be used as a vascular graft in the future (see

Fig. 12-54).

(the tibialis posterior muscle, the flexor digitorum longus muscle, the

posterior tibial artery and vein, the tibial nerve, and the flexor

hallucis longus tendon) are in danger if the deep surgical dissection

is not carried out close to bone (see Figs. 12-54, 12-55 and 12-56).

incision along the subcutaneous surface of the tibia. Subperiosteal

dissection exposes the subcutaneous and lateral surfaces of the tibia

along its entire length.

-

Arthrodesis of the ankle

-

Excision or fixation of osteochondral fragments from the medial side of the talus

-

Removal of loose bodies from the ankle joint

Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 5 minutes or by

applying a soft rubber bandage firmly; then inflate a tourniquet. The

natural external rotation of the leg exposes the medial malleolus. The

pelvis ordinarily does not have to be tilted to improve the exposure

(see Fig. 12-5).

|

|

Figure 12-13

Make a 10-cm longitudinal incision on the medial aspect of the ankle joint, with its center over the tip of the medial malleolus. Distally, curve the incision forward onto the medial side of the middle part of the foot. |

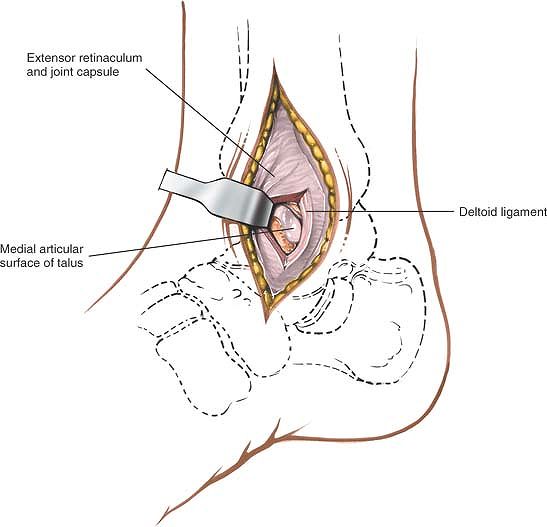

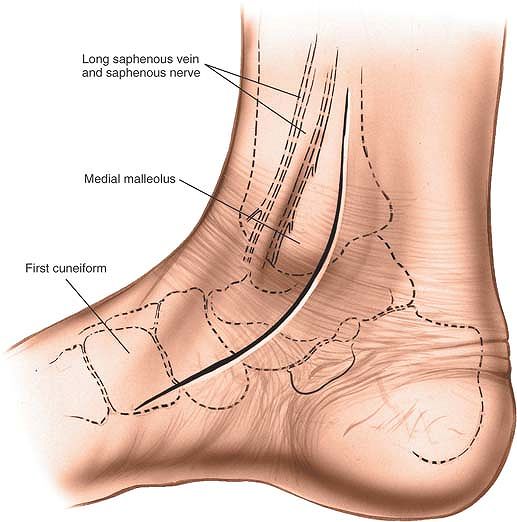

of the ankle joint, centering it on the tip of the medial malleolus.

Begin the incision over the medial surface of the tibia. Below the

malleolus, curve it forward onto the medial side of the middle part of

the foot (Fig. 12-13).

the surgery is safe because the tibia is subcutaneous and all

dissection stays on bone.

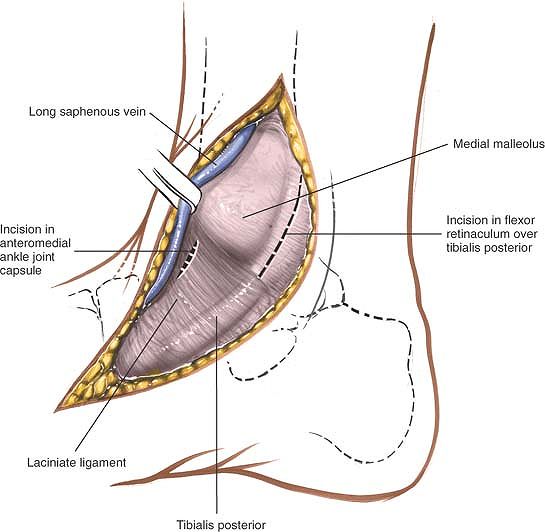

long saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve, which run together along

the anterior border of the medial malleolus (Fig. 12-14).

the shaft of the tibia, make a small longitudinal incision in the

anterior part of the joint capsule.

the tibialis posterior muscle, which runs immediately behind the medial

malleolus, grooving the bone (see Fig. 12-14). Retract the tendon posteriorly to expose the posterior surface of the malleolus (Fig. 12-15A).

|

|

Figure 12-14

Carefully retract the skin flaps to protect the long saphenous vein and the accompanying saphenous nerve. Incise the posterior retinaculum, and make a small incision into the anterior joint capsule. |

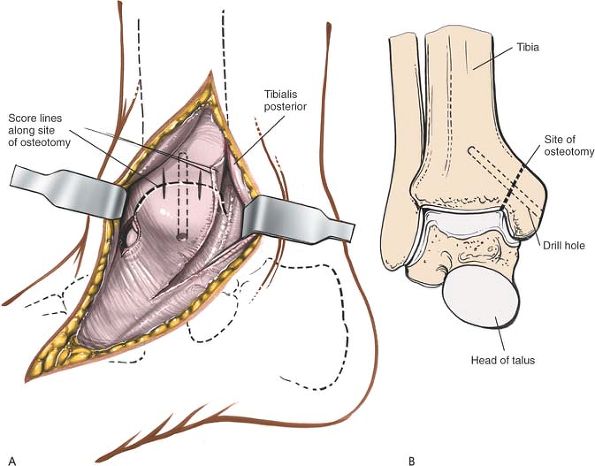

alignment of the malleolus during closure. Then, drill and tap the

medial malleolus so that it can be reattached (see Fig. 12-15B).

medial malleolus obliquely from top to bottom; cut laterally at its

junction with the shaft of the tibia, checking the position of the cut

through the incision in the anterior joint capsule (see Fig. 12-15).

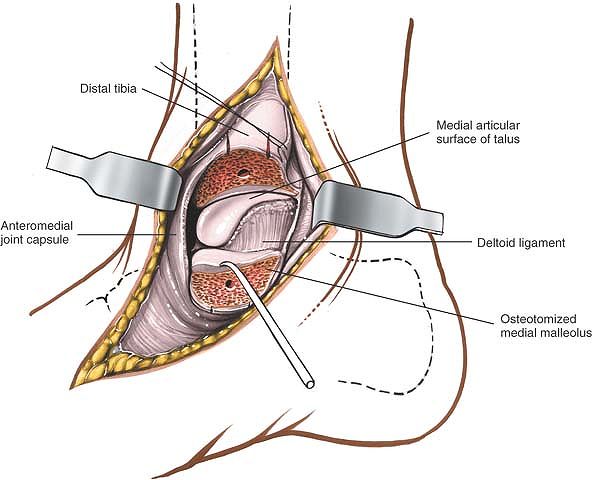

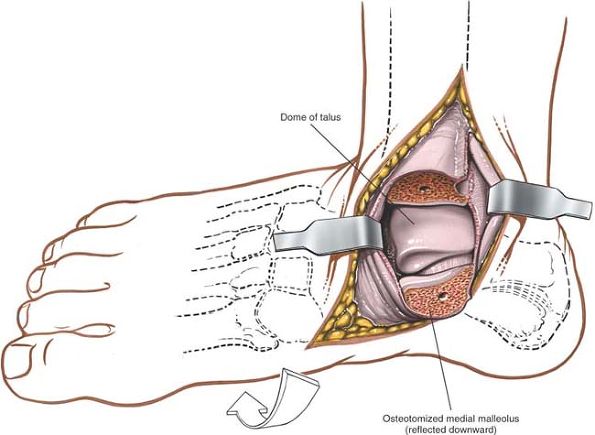

ligaments) downward and forcibly evert the foot, bringing the dome of

the talus and the articulating surface of the tibia into view (Figs. 12-16 and 12-17). Eversion is limited because of the intact fibula.

|

|

Figure 12-15 (A)

Retract the tibialis tendon posteriorly. Drill and tap the medial malleolus, and score the potential osteotomy site for future alignment. (B) The line of the osteotomy and the score marks for the reattachment of the medial malleolus. |

|

|

Figure 12-16 Retract the osteotomized medial malleolus downward.

|

|

|

Figure 12-17 Forcefully evert the foot to bring the dome of the talus and the anterior surface of the tibia into view.

|

long saphenous vein should be preserved as a unit, largely to prevent

damage to the saphenous nerve and subsequent neuroma formation.

is in particular danger during this approach, because it lies

immediately posterior to the medial malleolus. Preserve the tendon by

releasing and retracting it while performing osteotomy of the malleolus

(see Figs. 12-14 and 12-15A).

The tendons of the flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus

muscle, together with the posterior neurovascular bundle, lie more

posteriorly and laterally. They are in no danger as long as the

osteotomy is performed carefully (see Figs. 12-55 and 12-57).

ends of bone prevents rotation between the two fragments when a screw

is inserted and tightened. No such interdigitation exists in an

osteotomy. Therefore, two Kirschner wires should be used in addition to

a screw to prevent rotation when the screw is tightened. After the

osteotomy has been stabilized with the screw, the two Kirschner wires

can be removed. Tension band fixation also may be used. In any case,

align the bones correctly by aligning the score marks made on the bone

before the osteotomy.

routinely used for exploring the soft tissues that run around the back

of the medial malleolus. This approach is used for the release of soft

tissue around the medial malleolus in the treatment of clubfoot.

posterior malleolus of the ankle joint, but gives limited exposure of

the fracture site and is technically demanding. For this reason

reduction and fixation of posterior malleolar fractures is usually

achieved by indirect techniques.4

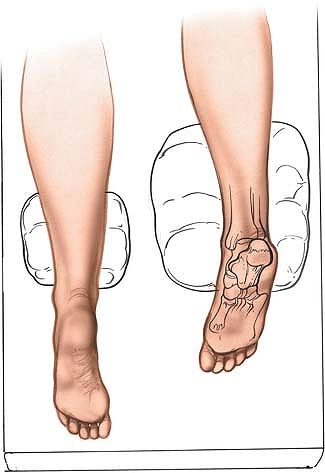

First, place the patient supine on the operating table. Flex the hip

and knee, and place the lateral side of the affected ankle on the

anterior surface of the opposite knee. This position will achieve full

external rotation of the hip, permitting better exposure of the medial

structures of the ankle (Fig. 12-18).

Alternatively, place the patient in the lateral position with the

affected leg nearest the table. Flex the knee of the opposite limb to

get its ankle out of the way.

|

|

Figure 12-18 Place the patient supine on the operating table with the knee and the hip flexed to expose the medial structures of the ankle.

|

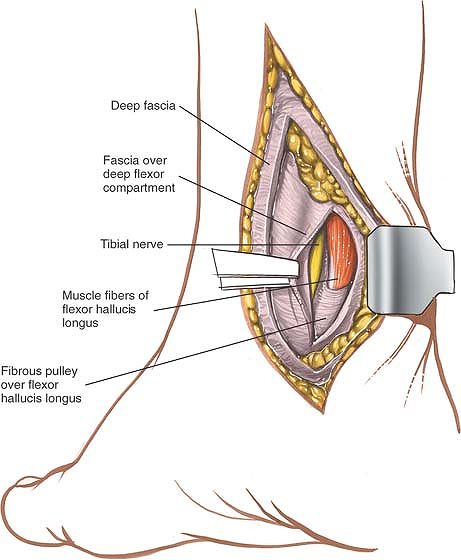

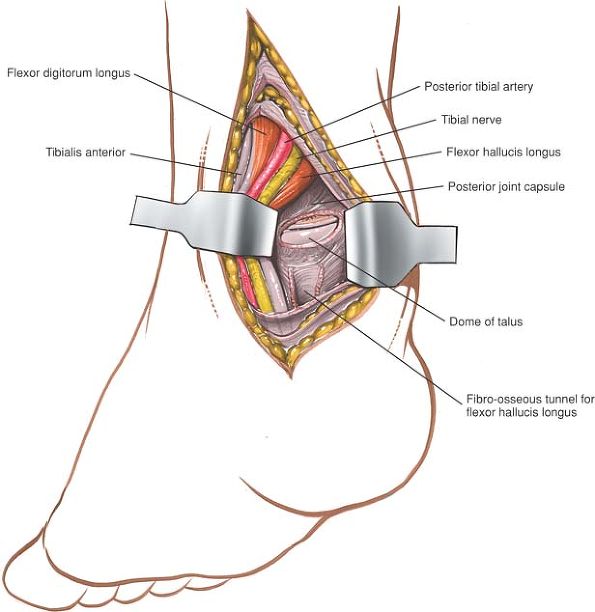

enter the fat that lies between the Achilles tendon and those

structures that pass around the back of the medial malleolus. If the

Achilles tendon must be lengthened, identify it in the posterior flap

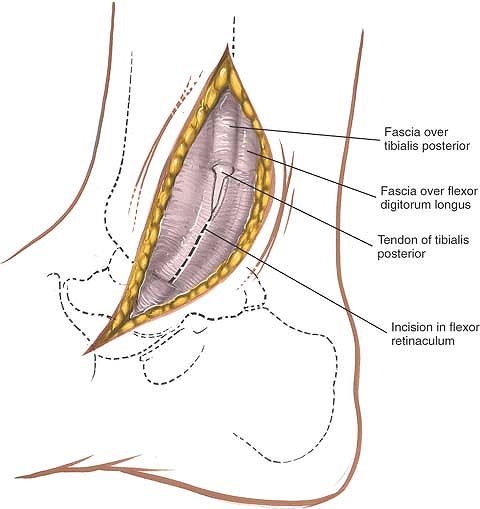

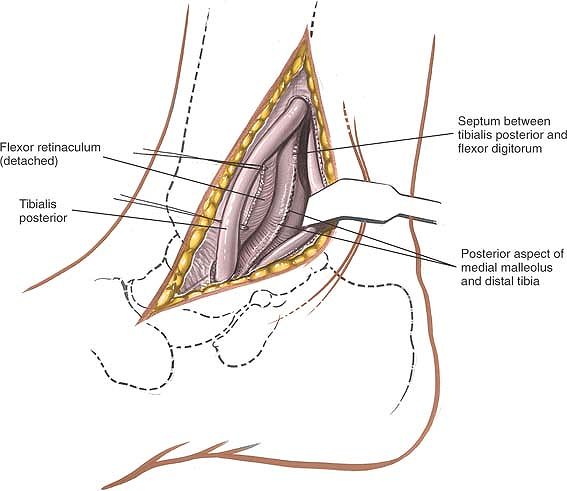

of the wound and perform the lengthening now. Identify a fascial plane

in the anterior flap that covers the remaining flexor tendons. Incise

the fascia longitudinally, well away from the back of the medial

malleolus (Figs. 12-20 and 12-21).

|

|

Figure 12-19 Make an 8- to 10-cm longitudinal incision roughly between the medial malleolus and the Achilles tendon.

|

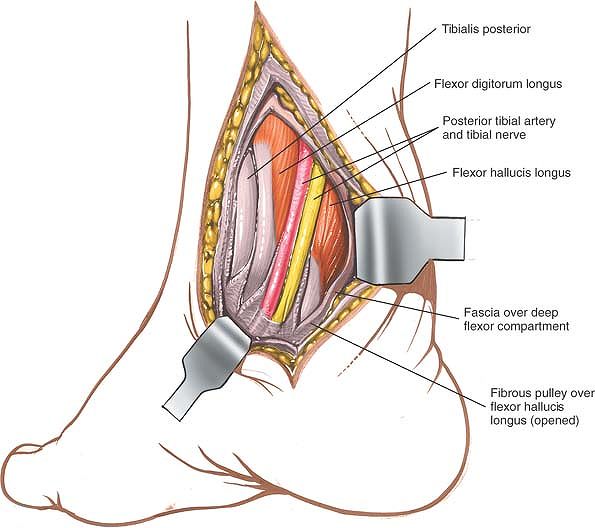

the dissection anteriorly toward the back of the medial malleolus.

Preserve the neurovascular bundle by mobilizing it gently and

retracting it and the flexor hallucis longus laterally to develop a

plane between the bundle and the tendon of the flexor digitorum

longus. This approach brings one onto the posterior aspect of the ankle joint rather more medially than does the first approach.

|

|

Figure 12-20 Incise the deep fascia in line with the skin incision.

|

|

|

Figure 12-21

Retract the Achilles tendon and the retrotendinous fat laterally, exposing the fascia of the deeper flexor compartment. Open the compartment, and identify the muscle fibers of the flexor hallucis longus. |

|

|

Figure 12-22

Identify the posterior tibial artery and tibial nerve. Then, incise the fibro-osseous tunnel over the flexor hallucis longus tendon and the other medial tendons so that the structures can be mobilized and retracted medially. |

the medial malleolus (the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus,

and flexor hallucis longus) must be lengthened, the back of the ankle

can be approached directly, because the posterior coverings of the

tendons must be divided during the lengthening procedure.

posterior neurovascular bundle) are vulnerable during the approach.

Take care not to apply forceful retraction to the nerve, as this may

lead to a neurapraxia. Note that the tibial nerve is surprisingly large

in young children and that the tendon of the flexor digitorum longus

muscle is extremely small. Take care to identify positively all

structures in the area before dividing any muscle tendons (see Figs. 12-54 and 12-55).

medial border of the ankle, ending over the talonavicular joint. This

extension exposes both the talonavicular joint and the master knot of

Henry. As is true for all long, curved incisions around the ankle, skin

necrosis can result if the skin flaps are not cut thickly or if

forcible retraction is applied.

|

|

Figure 12-23 Retract the posterior structures medially, exposing the posterior portion of the ankle joint.

|

of the posterior aspect of the distal tibia and ankle joint. It is well

suited for open reduction and internal fixation of posterior malleolar

fractures. Because the patient is prone, however, it is not the

approach of choice if the fibula and medial malleolus have to be fixed

at the same time. In such cases, it is better to use either a

posteromedial approach or a lateral approach to the fibula, and to

approach the posterolateral corner of the tibia through the site of the

fractured fibula. Neither of these approaches provides such good

visualization of the bone as does the posterolateral approach to the

ankle, but both allow other surgical procedures to be carried out

without changing the position of the patient on the table halfway

through the operation. Its other uses include the following:

-

Excision of sequestra

-

Removal of benign tumors

-

Arthrodesis of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint

-

Posterior capsulotomy and syndesmotomy of the ankle

-

Elongation of tendons

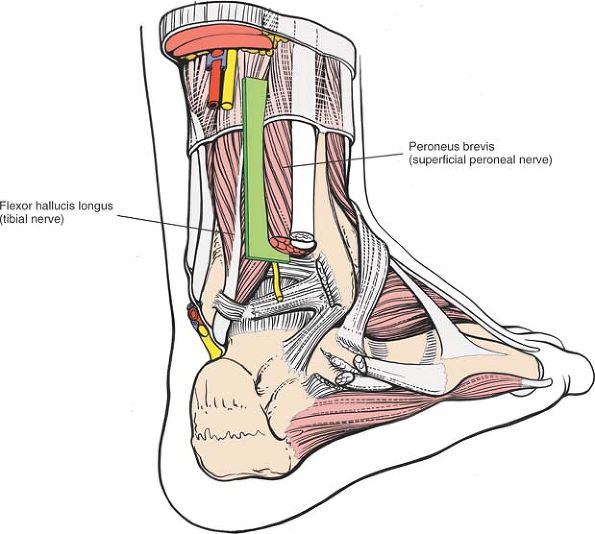

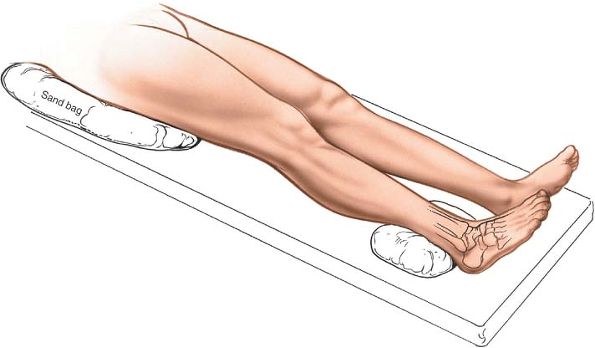

always, when the prone position is being used, longitudinal pads should

be placed under the pelvis and chest so that the center portion of the

chest and abdomen are free to move with respiration. A sandbag should

be placed under the ankle so that it can be extended during the

operation. Next, exsanguinate the limb by elevating it for 3 to 5

minutes or applying a soft rubber bandage; then inflate a tourniquet (Fig. 12-24).

|

|

Figure 12-24 Position of the patient for the posterolateral approach to the ankle joint.

|

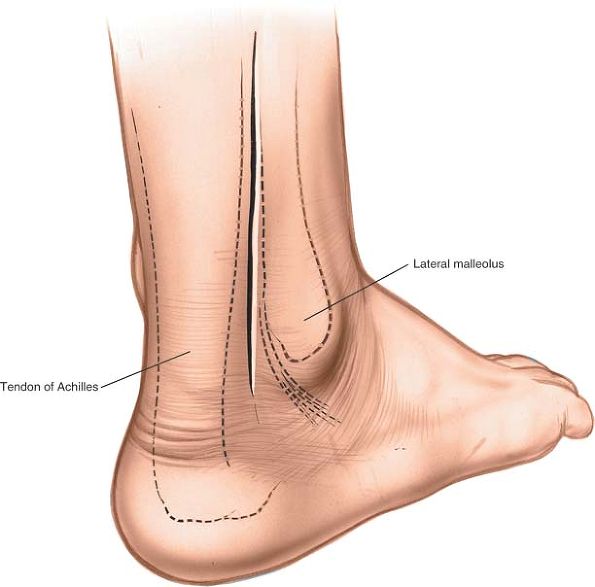

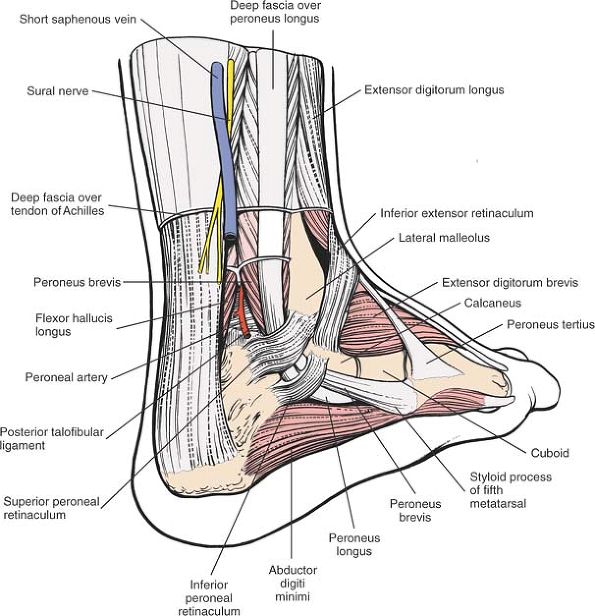

|

|

Figure 12-25 The internervous plane lies between the peroneus brevis (which is supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve) and the flexor hallucis longus (which is supplied by the tibial nerve).

|

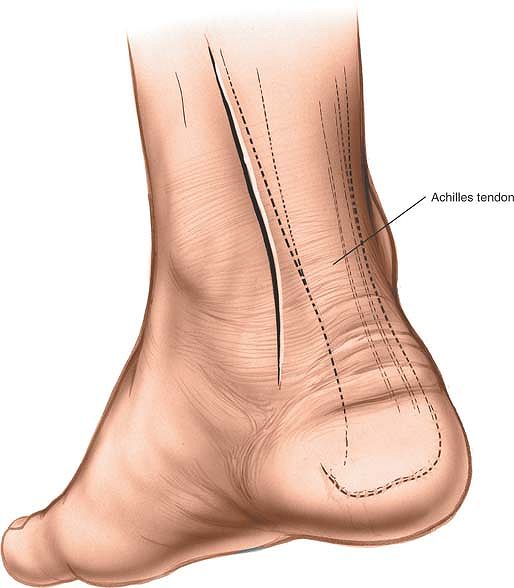

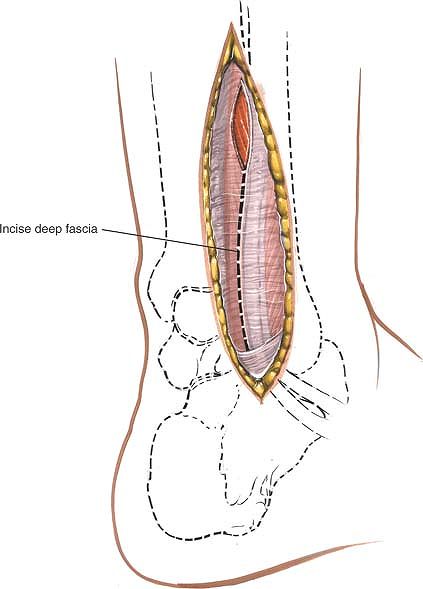

posterior border of the lateral malleolus and the lateral border of the

Achilles tendon. Begin the incision at the level of the tip of the

fibula and extend it proximally (Fig. 12-26).

sural nerves run just behind the lateral malleolus; they should be well

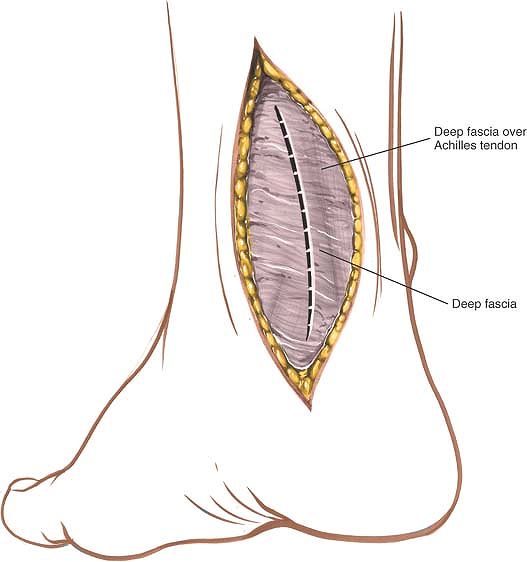

anterior to the incision. Incise the deep fascia of the leg in line

with the skin incision, and identify the two peroneal tendons as they

pass down the leg and around the back of the lateral malleolus (Fig. 12-27).

The tendon of the peroneus brevis muscle is anterior to that of the

peroneus longus muscle at the level of the ankle joint and, therefore,

is closer to the lateral malleolus. Note that the peroneus brevis is

muscular almost down to the ankle, whereas the peroneus longus is

tendinous in the distal third of the leg (see Figs. 12-64 and 12-65).

|

|

Figure 12-26

Make a 10-cm longitudinal incision halfway between the posterior border of the lateral malleolus and the lateral border of the Achilles tendon. |

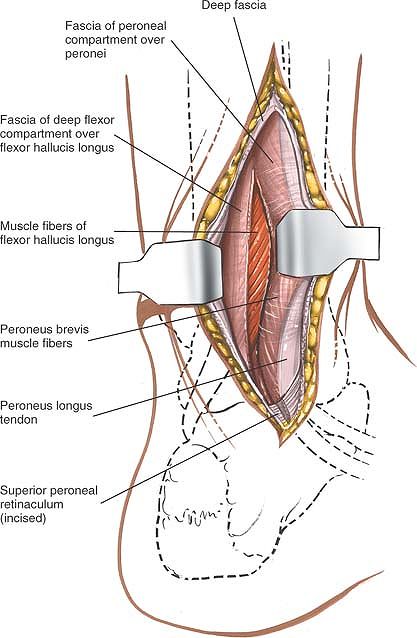

and retract the muscles laterally and anteriorly to expose the flexor

hallucis longus muscle (Fig. 12-28). The flexor

hallucis longus is the most lateral of the deep flexor muscles of the

calf. It is the only one that is still muscular at this level (see Fig. 12-65).

|

|

Figure 12-27

Mobilize the skin flaps. Incise the deep fascia of the leg in line with the skin incision. Identify the two peroneal tendons as they pass around the ankle. |

|

|

Figure 12-28

Incise the peroneal retinaculum to release the tendons. Retract them laterally and anteriorly. Incise the fascia over the flexor hallucis longus to expose its muscle fibers. |

|

|

Figure 12-29 Make a longitudinal incision through the lateral fibers of the flexor hallucis longus as they arise from the fibula.

|

|

|

Figure 12-30 Retract the flexor hallucis longus medially to reveal the periosteum covering the posterior aspect of the tibia.

|

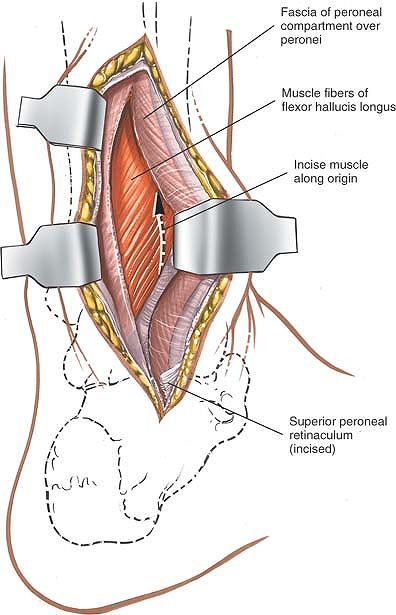

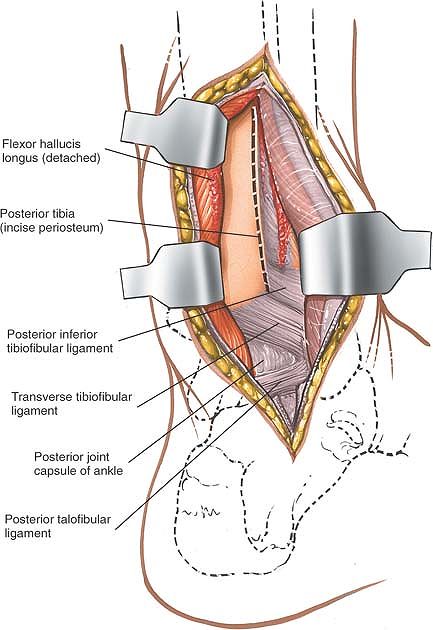

through the lateral fibers of the flexor hallucis longus muscle as they

arise from the fibula (Fig. 12-29). Retract the flexor hallucis longus medially to reveal the periosteum over the posterior aspect of the tibia (Fig. 12-30).

If the distal tibia must be reached, develop an epi-periosteal plane

between the periosteum covering the tibia and the overlying soft

tissues. To enter the ankle joint, follow the posterior aspect of the

tibia down to the posterior ankle joint capsule and incise it

transversely.

incision superiorly and identify the plane between the lateral head of

the gastrocnemius muscle and the peroneus muscles. Develop this plane

down to the soleus muscle; retract it medially with the gastrocnemius.

Next, reflect the flexor hallucis longus muscle medially, detaching it

from its origin on the fibula. Continue the dissection medially across

the interosseous membrane to the posterior aspect of the tibia (see Posterolateral Approach to the Tibia in Chapter 11).

for open reduction and internal fixation of lateral malleolar

fractures. It also offers access to the posterolateral aspect of the

tibia.

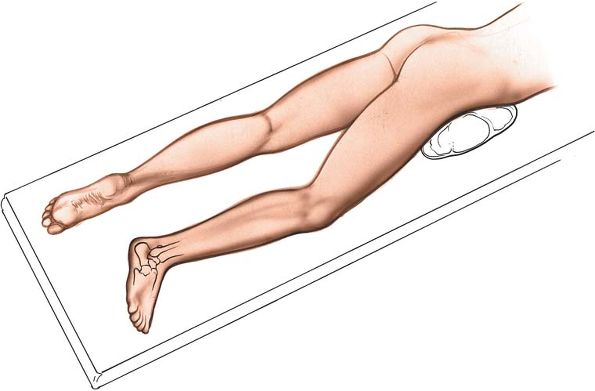

sandbag under the buttock of the affected limb. The sandbag causes the

limb to rotate medially, bringing the lateral malleolus forward and

making it easier to reach (Fig. 12-31). Tilt

the table away from you to further increase the internal rotation of

the limb. Operating with the patient on his or her side also provides

excellent access to the distal fibula, but the medial malleolus cannot

be reached unless the patient’s position is changed, something that is

necessary in the fixation of bimalleolar fractures (Fig. 12-32). Exsanguinate the limb by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes, then inflate a tourniquet.

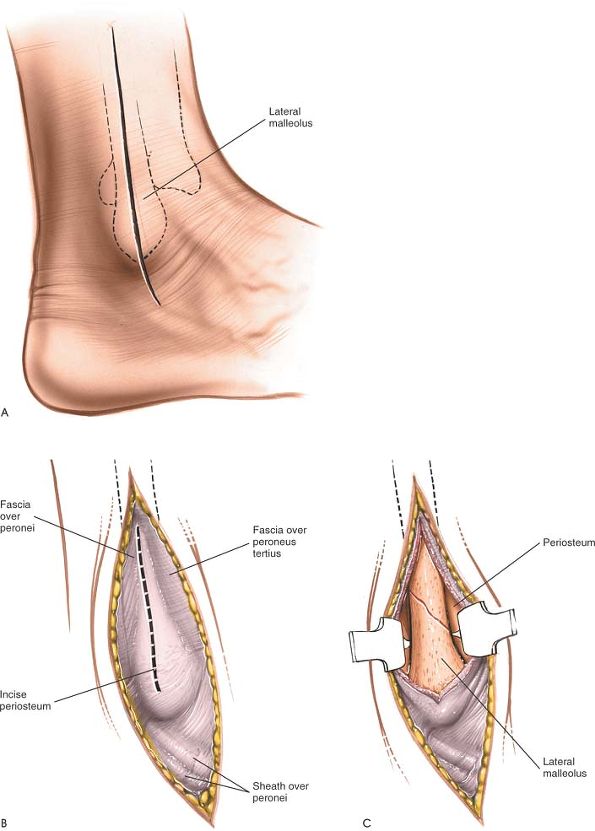

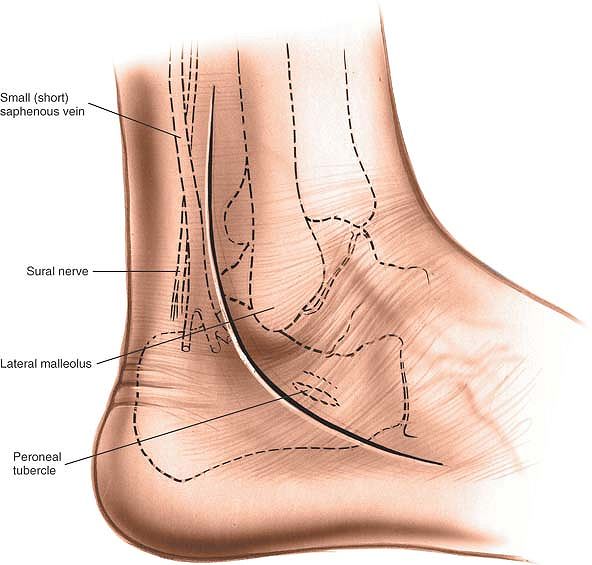

posterior margin of the fibula all the way to its distal end and

continuing for a further 2 cm (Fig. 12-33A). In fracture surgery, center the incision at the level of the fracture.

is being performed down to a subcutaneous bone. For higher fractures of

the fibula, the internervous plane lies between the peroneus tertius muscle (which is supplied by the deep peroneal nerve) and the peroneus brevis muscle (which is supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve). (See Approach to the Fibula in Chapter 11.)

short saphenous vein, which lies posterior to the lateral malleolus.

The sural nerve, which runs with the short saphenous vein, also should

be preserved.

enough of it at the fracture site to expose the fracture adequately.

Take care to keep all dissection strictly subperiosteal, because the

terminal branches of the peroneal artery, which lie close to the

lateral malleolus, may be damaged. Only strip off as much periosteum as

is necessary for accurate reduction; periosteal stripping markedly

reduces the blood supply of the bone in cases of fracture (Fig. 12-33B, C; see Fig. 12-64).

|

|

Figure 12-31 Position of the patient for exposure of the lateral malleolus.

|

|

|

Figure 12-32

An alternate position for exposure of the lateral malleolus. Place the patient prone or on his or her side, with a sandbag under the pelvis of the affected side. |

|

|

Figure 12-33 (A)

Make a 10- to 15-cm incision along the posterior margin of the fibula all the way to its distal end. From there, curve the incision forward, below the tip of the lateral malleolus. (B) Incise the periosteum on the subcutaneous surface of the fibula longitudinally. (C) Expose the distal fibula subperiosteally. |

mobilized. Cutting it may lead to the formation of a painful neuroma

and numbness along the lateral skin of the foot, which, although it

does not bear weight, does come in contact with the shoe. The nerve

also is valuable as a nerve graft. Preserve it if possible (see Fig. 12-61).

immediately deep to the medial surface of the distal fibula. They can

be damaged if dissection is extensive. The damage may not be noticed

during surgery because of the tourniquet, but a hematoma may form after

the tourniquet is taken off. That is why it is best to deflate the

tourniquet before closure to ensure hemostasis; then, the wound can be

drained with a suction drain (see Fig. 12-64).

the incision along the posterior border of the fibula, incising the

deep fascia in line with the skin incision. Develop a new plane between

the peroneal muscles (which are supplied by the superficial peroneal

nerve) and the flexor muscles (which are supplied by the tibial nerve).

The upper third of the fibula can be exposed if the common peroneal

nerve can be identified near the knee and traced down toward the ankle.

(For details of this approach, see Approach to the Fibula in Chapter 11.)

extend the approach distally, curve the incision down the lateral side

of the foot. Identify the peroneal tendons and incise the peroneal

retinacula. Detach the fat pad in the sinus tarsi and the origin of the

extensor digitorum brevis muscle to expose the calcaneocuboid joint on

the lateral side of the tarsus (see Figs. 12-61 and 12-62).

ankle and hindpart of the foot allows exposure not only of the ankle

joint, but also of the talonavicular, calcaneocuboid, and talocalcaneal

joints. The approach is used commonly for ankle fusions, but also can

be used for triple arthrodesis and even pantalar arthrodesis. In

addition, it is possible to excise the entire talus through this

approach, or to reduce it in cases of talar dislocation.

large sandbag underneath the affected buttock to rotate the leg

internally and bring the lateral malleolus forward. Exsanguinate the

limb either by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft

rubber bandage; then inflate a tourniquet (see Fig. 12-31).

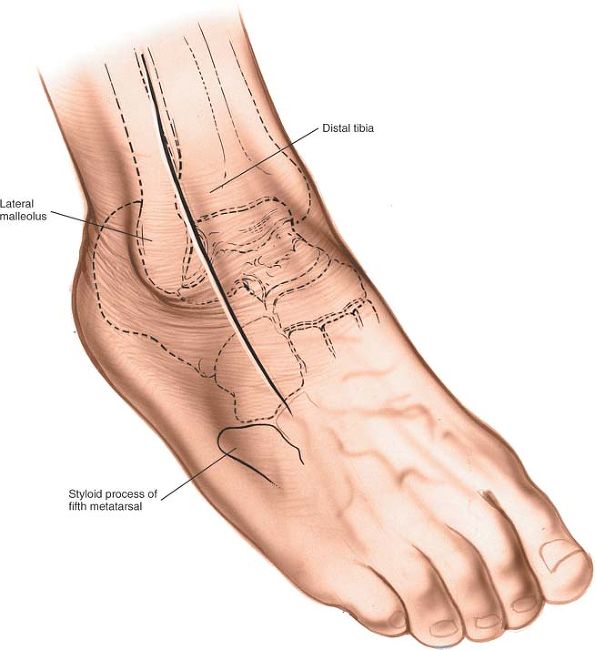

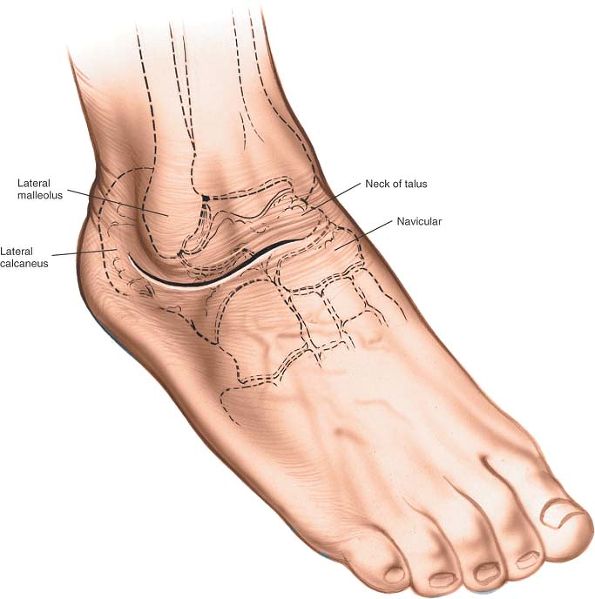

anterolateral aspect of the ankle. Begin some 5 cm proximal to the

ankle joint, 2 cm anterior to the anterior border of the fibula. Curve

the incision down, crossing the ankle joint 2 cm medial to the tip of

the lateral malleolus, and continue onto the foot, ending some 2 cm

medial to the fifth metatarsal base, over the base of the fourth

metatarsal (Fig. 12-34).

|

|

Figure 12-34

Incision for the anterolateral approach to the ankle. Make a 15-cm slightly curved incision on the anterolateral aspect of the ankle. Begin approximately 5 cm proximal to the ankle joint and 2 cm anterior to the anterior border of the fibula. Curve the incision downward to cross the ankle joint 2 cm medial to the tip of the lateral malleolus, and continue onto the foot, ending about 2 cm medial to the fifth metatarsal. |

|

|

Figure 12-35

Incise the deep fascia and the superior and inferior retinacula in line with the incision. Take care to preserve the superficial peroneal nerve. |

|

|

Figure 12-36

Identify the peroneus tertius and the extensor digitorum longus muscles, and incise down to bone lateral to them in the upper half of the wound. |

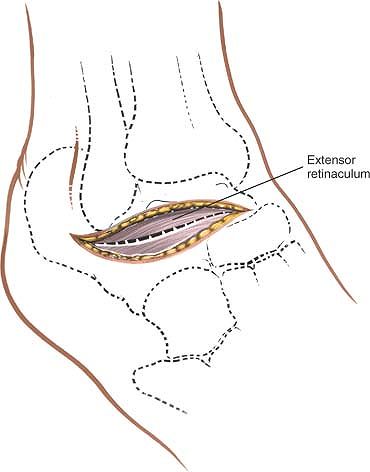

cutting through the superior and inferior extensor retinacula. Do not

develop skin flaps. Take care to identify and preserve any dorsal

cutaneous branches of the superficial peroneal nerve that may cross the

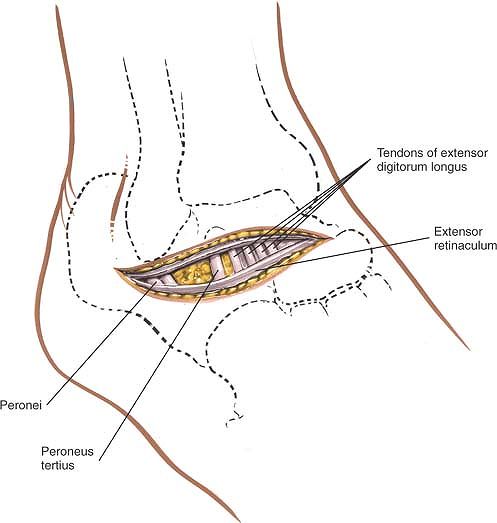

field of dissection (Fig. 12-35). Identify the

peroneus tertius and extensor digitorum longus muscles, and, in the

upper half of the wound, incise down to bone just lateral to these

muscles (Fig. 12-36).

|

|

Figure 12-37

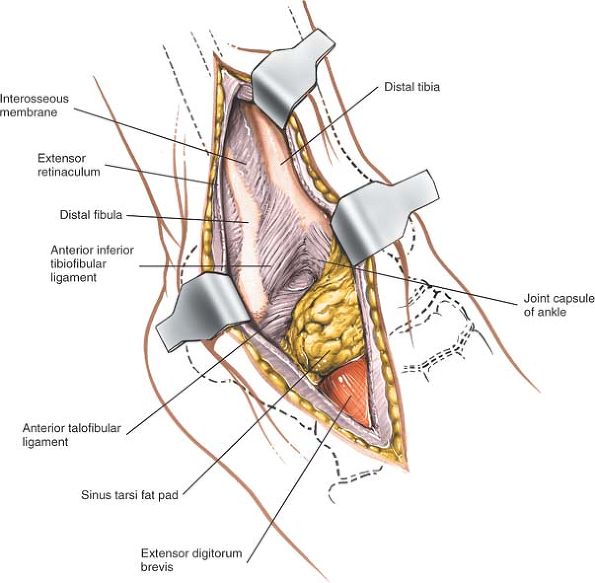

Retract the extensor musculature medially to expose the anterior aspect of the distal tibia and ankle joint. Identify the origin of the extensor digitorum brevis. |

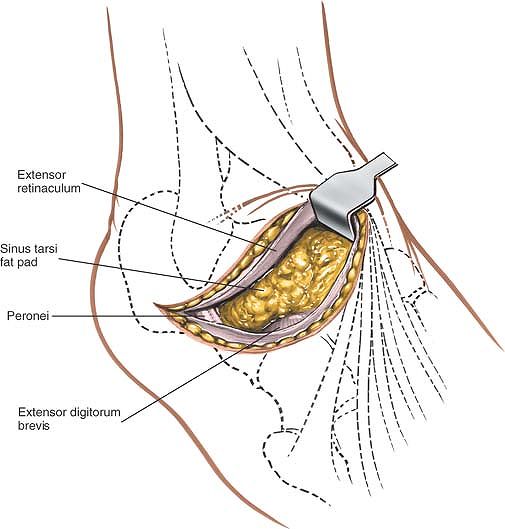

anterior aspect of the distal tibia and the anterior ankle joint

capsule. Distally, identify the extensor digitorum brevis muscle at its

origin from the calcaneus (Fig. 12-37) and

detach it by sharp dissection. During dissection, branches of the

lateral tarsal artery will be cut; cauterize (diathermy) these to

prevent the formation of a postoperative hematoma. Reflect the detached

extensor digitorum brevis muscle distally and medially, lifting the

muscle fascia and the subcutaneous fat and skin as one flap. Identify

the dorsal capsules of the calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joints,

which lie next to each other across the foot, forming the clinical

midtarsal joint (see Fig. 12-60). Next,

identify the fat in the sinus tarsi and clear it away to expose the

talocalcaneal joint, either by mobilizing the fat pad and turning it

downward or by excising it.

Preserving

the fat pad prevents the development of a cosmetically ugly dimple

postoperatively. Preserving the pad also helps the wound to heal (Fig. 12-38).

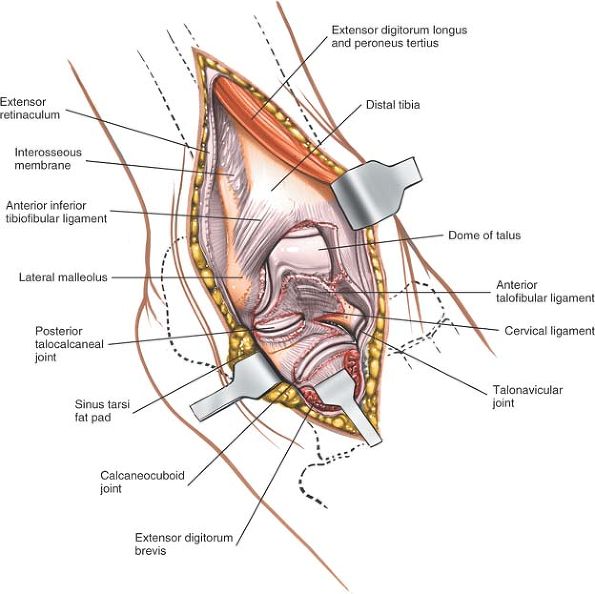

exposed. To open the joints, forcefully flex and invert the foot in a

plantar direction (see Fig. 12-38).

|

|

Figure 12-38

The extensor digitorum brevis has been detached from its origin and reflected distally. The fat pad covering the sinus tarsi has been detached and reflected downward. Incise the joint capsules that have been exposed. |

structures in the anterior compartment of the leg. Continue the

incision over the compartment, and incise the thick deep fascia in line

with the skin incision.

tarsometatarsal joint on the lateral half of the foot. Continue the

incision over the fourth metatarsal, and expose the subcutaneous

tarsometatarsal joints.

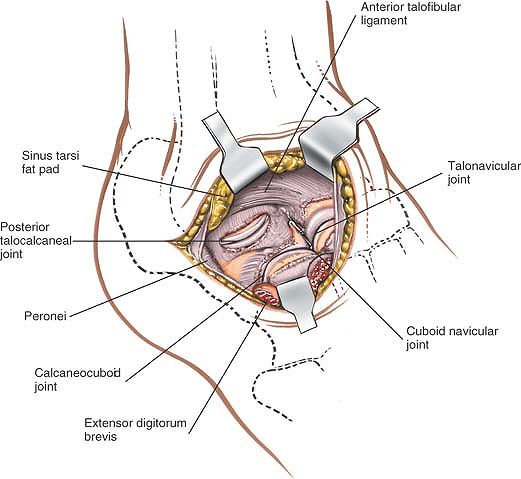

talocalcaneonavicular, posterior talocalcaneal, and calcaneocuboid

joints. It permits arthrodesis of any or all these joints (triple

arthrodesis).

Place a large sandbag beneath the affected buttock to rotate the leg

internally, and bring the lateral portion of the ankle and hindpart of

the foot forward. Further increase internal rotation by tilting the

table away from you. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 5

minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage, and then inflate a

tourniquet (see Fig. 12-31).

|

|

Figure 12-39

Make a curved incision starting just distal to the distal end of the lateral malleolus and slightly posterior to it. Continue distally along the lateral side of the hindpart of the foot and over the sinus tarsi. Then, curve the incision medially toward the talocalcaneonavicular joint. |

stabilize the foot, holding the calcaneus with one hand, and place the

thumb of the free hand in the soft-tissue depression just anterior to

the lateral malleolus. The depression lies directly over the sinus

tarsi.

distal end of the lateral malleolus and slightly posterior to it.

Continue distally along the lateral side of the hindpart of the foot

and over the sinus tarsi. Then, curve medially, ending over the

talocalcaneonavicular joint (Fig. 12-39).

skin flaps may necrose. Ligate any veins that cross the operative

field. Open the deep fascia in line with the skin incision, taking care

not to damage the tendons of the peroneus tertius and extensor

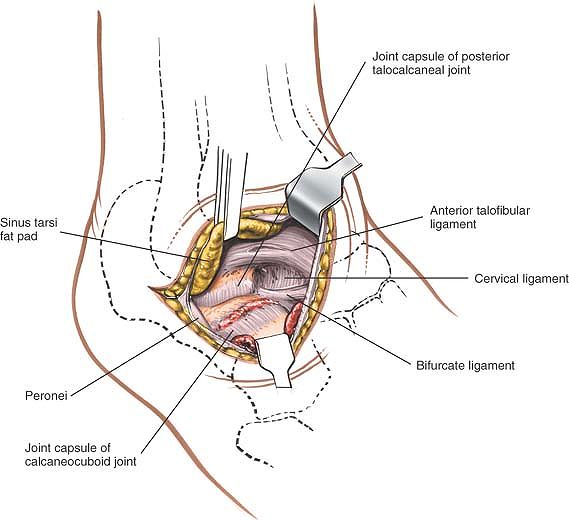

digitorum longus muscles, which cross the distal end of the incision (Figs. 12-40 and 12-41).

Retract these tendons medially to gain access to the dorsum of the

foot. Do not retract the peroneal tendons, which run through the

proximal end of the wound, at this stage (Fig. 12-42).

|

|

Figure 12-40 Incise and open the deep fascia in line with the skin incision.

|

|

|

Figure 12-41

Take care not to damage the tendons of the peroneus tertius and the extensor digitorum longus, which cross under the distal end of the incision. |

|

|

Figure 12-42 Retract the extensor tendons medially.

|

tarsi by sharp dissection, leaving it attached to the skin flap; under

it lies the origin of the extensor digitorum brevis muscle. Detach its

origin by sharp dissection, and reflect the muscle distally to expose

the dorsal capsule of the talocalcaneonavicular joint in the distal end

of the wound and the dorsal capsule of the calcaneocuboid joint more

laterally (Fig. 12-43). Incise these capsules and open their respective joints by inverting the foot forcefully (Fig. 12-44).

Next, incise the peroneal retinacula and reflect the peroneal tendons

anteriorly. Identify and incise the capsule of the posterior

talocalcaneal joint. Open it by inverting the heel (Fig. 12-45).

calcaneocuboid joints now are exposed. Note that, in virtually all

cases in which this approach is used, these joints are in abnormal

position. The approach should remain safe as long as it stays on bone

while the joints are being identified.

necrosis of skin flaps. Therefore, skin flaps should be cut as thickly

as possible, stripping and retraction should be kept to a minimum, and

sharp curves in the skin incision should be avoided.

subtalar joint must be incised before inversion will open either one.

|

|

Figure 12-43

Retract the fat pad with the skin flap. Detach the origins of the extensor digitorum brevis, and retract the muscle distally to expose the dorsal capsule of the talocalcaneonavicular joint in the distal end of the wound and the more lateral dorsal capsule of the calcaneocuboid joint. |

|

|

Figure 12-44 Incise the joint capsules of the respective joints.

|

|

|

Figure 12-45 Reflect the peroneal tendons anteriorly. Incise the joint capsule of the posterior talocalcaneal joint.

|

incision, curving it along the posterior border of the fibula. By

developing a plane between the peroneal muscles and the flexor muscles,

the entire length of the fibula can be exposed (see Approach to the Fibula in Chapter 11). In practice, however, this extension is required rarely, if ever.

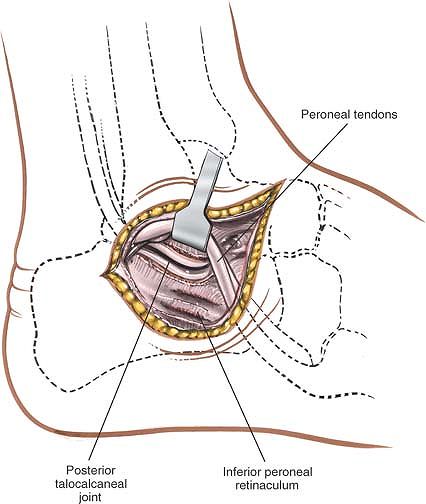

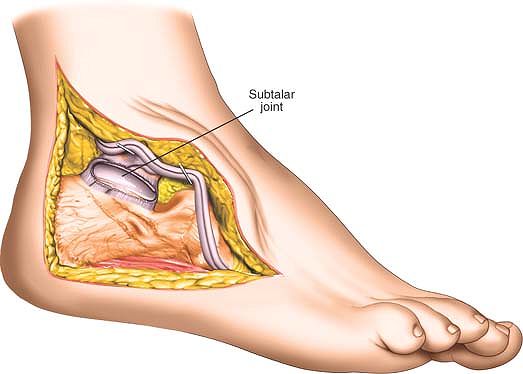

joint exposes the posterior facet of the talocalcaneal joint more

extensively than does the anterolateral approach. It is mainly used for

arthrodesis of the posterior part of the talocalcaneal joint.

sandbag under the buttock of the affected side to bring the lateral

malleolus forward. Place a support

on

the opposite iliac crest, then tilt the table 20° to 30° away from the

surgeon to improve access still further. Exsanguinate the limb either

by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber

bandage; then inflate a tourniquet (see Fig. 12-31).

is a small protuberance of bone on the lateral surface of the calcaneus

that separates the tendons of the peroneus longus and brevis muscles.

It lies distal and anterior to the lateral malleolus.

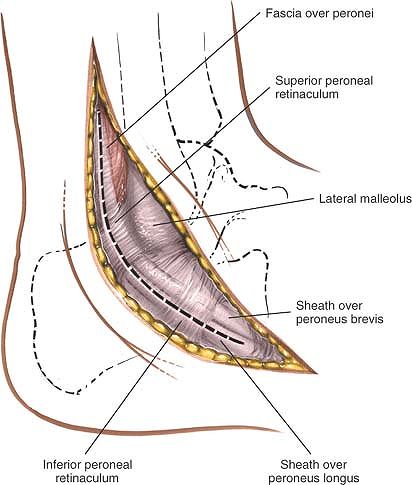

aspect of the ankle. Begin some 4 cm above the tip of the lateral

malleolus on the posterior border of the fibula. Follow the posterior

border of the fibula down to the tip of the lateral malleolus, and then

curve the incision forward, passing over the peroneal tubercle parallel

to the course of the peroneal tendons (Fig. 12-46).

|

|

Figure 12-46 Make a curved incision 10 to 13 cm long on the lateral aspect of the ankle.

|

peroneus muscles, whose tendons are mobilized and retracted anteriorly,

share a nerve supply from the superficial peroneal nerve. The approach

is safe because the muscles receive their supply at a point well

proximal to it.

malleolus with the short saphenous vein. Begin incising the deep fascia

in line with the upper part of the skin incision to uncover the two

peroneal tendons. The tendons of the peroneus longus and peroneus

brevis muscles curve around the back of the lateral malleolus. The

peroneus brevis tendon, which is closest to the lateral malleolus, is

muscular almost down to the level of the malleolus itself (see Fig. 12-61).

|

|

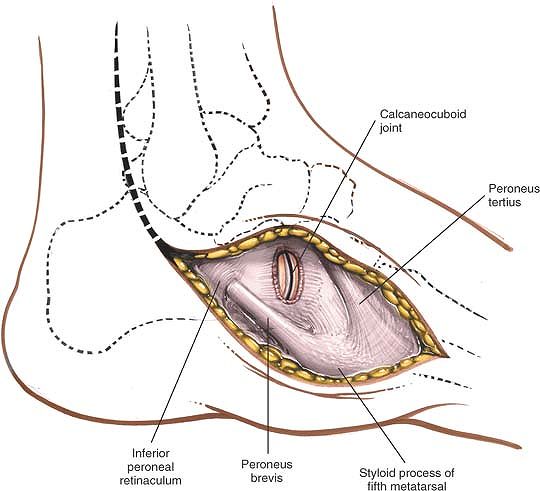

Figure 12-47

Incise the deep fascia in line with the upper part of the skin incision. Continue the fascial incision distally, following the course of the tendons. Incise the inferior peroneal retinaculum, and expose the peroneal tendons. |

tendons. The peroneus brevis is covered by the inferior peroneal

retinaculum distal to the tip of the fibula. Incise it in line with the

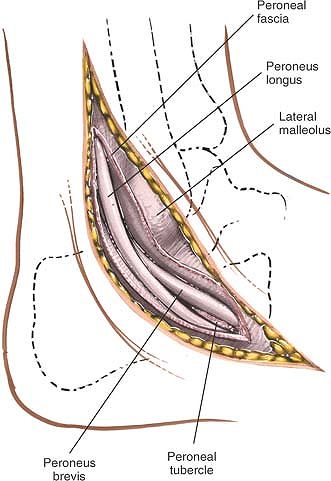

tendon (Fig. 12-47). The peroneus longus is

covered by a separate fibrous sheath of its own; incise that sheath in

line with the tendon as well. These ligaments of the retinaculum must

be repaired during closure to prevent tendon dislocation (Fig. 12-48). When both peroneal tendons have been mobilized, retract them anteriorly over the distal end of the fibula (Fig. 12-49).

|

|

Figure 12-48

Incise the deep fascia in line with the upper part of the skin incision. Continue the fascial incision distally, following the course of the tendons. Incise the inferior peroneal retinaculum and expose the peroneal tendons. |

|

|

Figure 12-49

Mobilize the peroneal tendons, and retract them anteriorly over the distal end of the fibula. Identify the calcaneofibular ligament. Incise it transversely to open the capsule of the posterior talocalcaneal joint. |

|

|

Figure 12-50 Open the joint capsule to expose the posterior talocalcaneal joint.

|

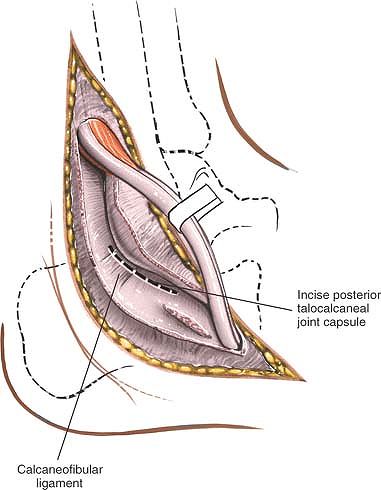

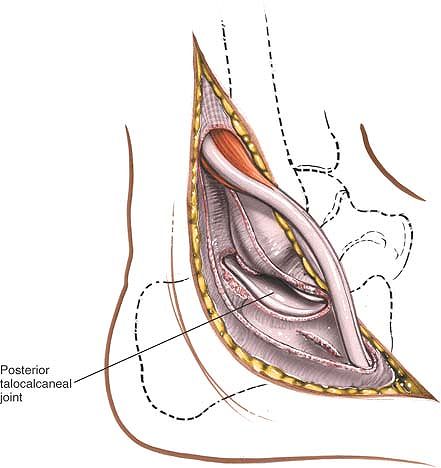

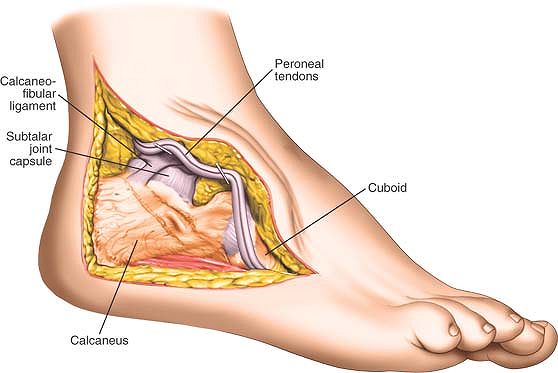

the lateral malleolus down and back to the lateral surface of the

calcaneus. The ligament is bound closely to the capsule of the

talocalcaneal joint. The joint itself is difficult to palpate and

identify, and a small amount of subperiosteal dissection on the lateral

aspect of the calcaneus usually is required before the joint can be

located. Having identified the joint, incise the capsule transversely

to open it up (Fig. 12-50; see Figs. 12-49, 12-62, and 12-63).

incise the peritoneum over its lateral surface and strip it inferiorly

by sharp dissection. To see the talus better, cut the calcaneofibular

ligament and the capsule of the talocalcaneal joint superiorly to

uncover its lateral border.

achieved only by inverting the foot. Forcible inversion does not open

up the joint if the anterior part of the talocalcaneal

(talocalcaneonavicular) joint remains intact.

for open reduction and internal fixation of calcaneal fractures. Such

fractures are always associated with significant soft-tissue swelling;

it is critical to allow this soft-tissue swelling to subside before

surgery is carried out to reduce the risk of skin necrosis. An accurate

assessment of the vascular status of the patient is critical before

undertaking surgery. Diabetes, especially with associated neuropathy

and smoking, are relative contraindications to this surgery approach.

The indications for the surgical approach include:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of displaced calcaneal fractures

-

Treatment of other lesions of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint and lateral wall of the os calcis

operating table. Ensure that the bony prominences are well padded.

Place the leg that is to be operated on posteriorly with the under leg

anterior. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 3 to 5

minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage. Inflate a tourniquet.

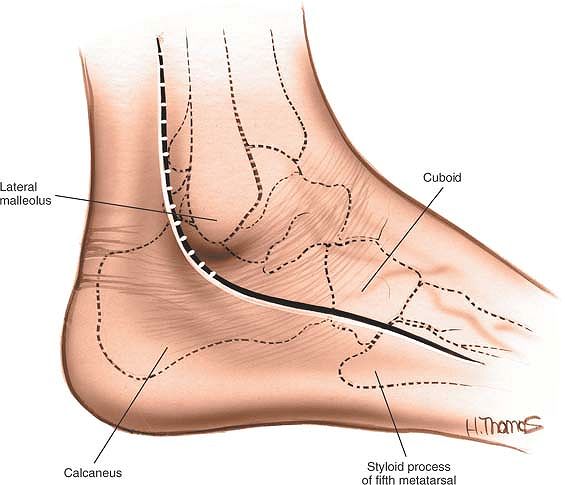

the lateral border of the Achilles tendon. Next, identify the styloid

process at the base of the fifth metatarsal bone, which is easily felt

along the lateral aspect of the foot.

of the incision at the base of the fifth metatarsal and extend it

posteriorly, following the junction between the smooth skin of the

dorsum of the foot and the wrinkled skin of the sole. Make a second

incision beginning approximately 6 to 8 cm above the skin of the heel,

halfway between the posterior aspect of the fibula and the lateral

aspect of the Achilles tendon. Extend this second incision distally to

meet the first incision overlying the lateral aspect of the os calcis (Fig. 12-51).

taking care not to elevate any flaps. Distally, dissect straight down

to the lateral surface of the calcaneus by sharp dissection (Fig. 12-52).

|

|

Figure 12-51

Begin the distal limb of the incision at the base of the fifth metatarsal and extend it posteriorly, following the junction between the smooth skin of the dorsum of the foot and the wrinkled skin of the sole. Make a second incision beginning approximately 6 to 8 cm above the skin of the heel, halfway between the posterior aspect of the fibula and the lateral aspect of the Achilles tendon. Extend this second incision distally to meet the first incision overlying the lateral aspect of the os calcis. |

calcaneus and develop a full thickness flap consisting of periosteum

and all the overlying tissues. Stick to the bone and continue to

retract the soft tissue flap proximally. The peroneal tendons will be

carried forward with the flap. Divide the calcaneofibular ligament to

expose the subtalar joint. Continue the dissection proximally to expose

the body of the os calcis as well as the subtalar joint. Distally

expose the calcaneocuboid joint by incising its capsule. If at all

possible, try not to cut into the muscle belly of abductor digiti

minimae (Fig. 12-53).

|

|

Figure 12-52

Deepen the skin incision through subcutaneous tissue, taking care not to elevate any flaps. Distally dissect straight down to the lateral surface of the calcaneus by sharp dissection. Next, elevate a thick flap consisting of periosteum subcutaneous tissues and skin. The peroneal tendons will be elevated in this flap. Do not attempt to dissect out layers in this flap. |

|

|

Figure 12-53

Continue to develop the anterior flap. Divide the calcaneofibular ligament to expose the subtalar joint. Continue the dissection proximally to expose the body of the os calcis as well as the subtalar joint. Distally expose the calcaneocuboid joint by incising its capsule. |

The risk of skin necrosis can be minimized if the flap is elevated as a

full thickness flap because the skin derives its blood supply from the

underlying tissues. Dissecting the skin flaps in this area, which has

always been severely traumatized, is associated with a significant

incidence of wound breakdown. Accurate assessment of the patient’s

preoperative vascular status is critical. Most surgery in this area has

to be delayed for a significant period of time to allow soft-tissue

swelling to diminish before surgery commences.

to the Achilles and plantaris tendons, which lie posteriorly in the

midline.

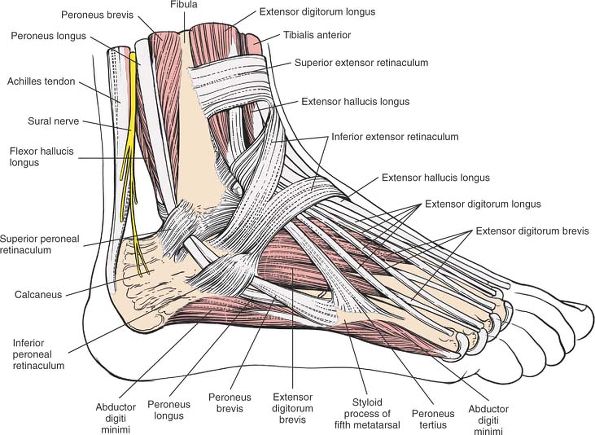

-

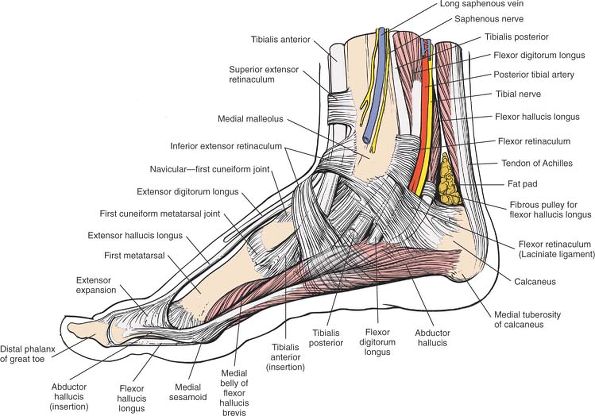

The flexor tendons—the tibialis

posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus (which

are supplied by the tibial nerve)—pass behind the medial malleolus. -

The extensor tendons—the tibialis

anterior, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus, and

peroneus tertius (which are supplied by the deep peroneal nerve)—pass

in front of the ankle joint. -

The evertor tendons—the peroneus longus

and peroneus brevis (which are supplied by the superficial peroneal

nerve)—pass behind the lateral malleolus.

the ankle by thickened areas in the deep fascia of the leg, called the

retinacula.

potential internervous planes through which the ankle can be

approached: medially, between flexors (tibialis posterior) and

extensors (tibialis anterior); posterolaterally, between flexors

(flexor hallucis longus) and evertors (peroneus brevis); and laterally,

between extensors (peroneus tertius) and evertors (peroneus brevis).

|

|

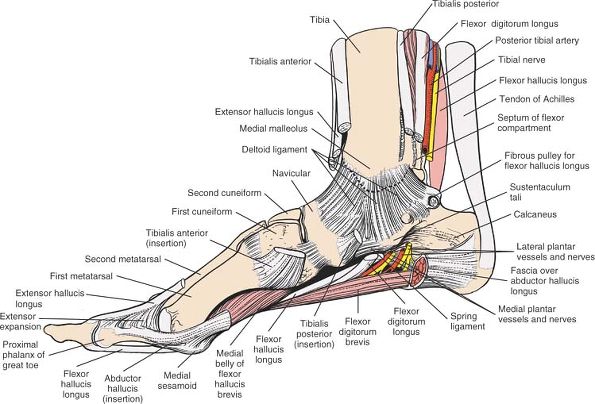

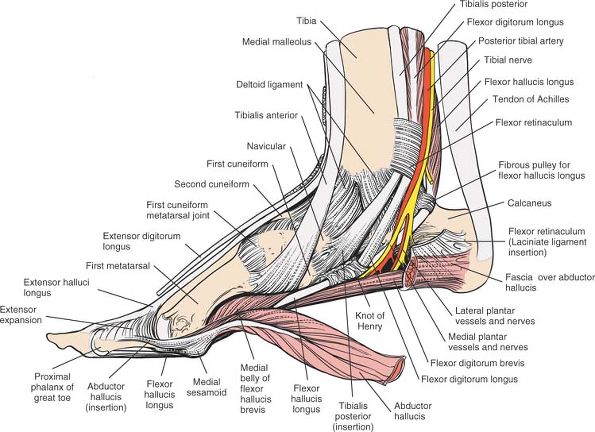

Figure 12-54

The superficial structures of the medial aspect of the foot and ankle. Fibers of the flexor retinaculum cross the neurovascular bundle, binding it to the medial side of the foot. |

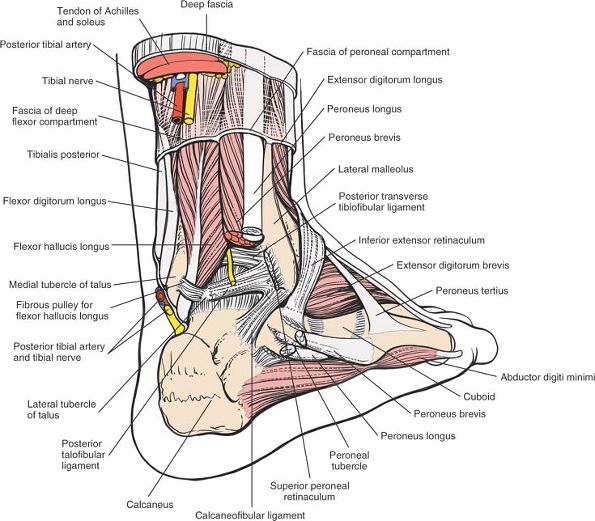

and supply the foot. They present the major surgical concerns for all

approaches around the ankle.

-

The anterior neurovascular bundle

crosses the front of the ankle roughly halfway between the malleoli. It

lies between the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus muscles

proximal to the joint (see Fig. 12-59), and

between the tendons of the extensor hallucis longus and extensor

digitorum longus muscles distal to the joint. The tendon of the

extensor hallucis longus crosses the bundle in a lateral to medial

direction at the level of the ankle joint (see Fig. 12-58).The anterior tibial artery,

which crosses the front of the ankle joint before becoming the dorsalis

pedis artery, is palpable on the dorsum of the foot. It also

communicates with the medial plantar artery through the first

metatarsal space. Fractures through the base of the metatarsal bones

and dislocations at the tarsometatarsal joint (Lisfranc’s

fracture/dislocation)* can damage both elements of this anastomosis and

cause ischemia to the medial side of the distal portion of the foot.The deep peroneal nerve

accompanies the anterior tibial artery. It supplies two small muscles

on the dorsum of the foot: the extensor digitorum brevis and the

extensor hallucis brevis. It also supplies a sensory branch to the

first web space. Anesthesia in this web space is one of the first

clinical signs of anterior compartment compression. Ischemia of

P.669

the deep peroneal nerve occurs before ischemic muscle damage (see Figs. 12-58 and 12-59). Figure 12-55

Figure 12-55

The extensor retinaculum and part of the flexor retinaculum have been

removed to reveal the deeper tendons and the neurovascular bundle. The

abductor hallucis has been detached from its origin to reveal the knot

of Henry and the medial and lateral plantar arteries and nerves. -

The posterior neurovascular bundle runs behind the medial malleolus, between the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus muscles (Figs. 12-54 and 12-55).

passes behind the flexor digitorum longus before entering the sole of

the foot, where it divides into medial and lateral plantar arteries

(see Fig. 12-55).

behind the medial malleolus with the posterior tibial artery. It gives

off a calcaneal branch to the skin of the heel. After entering the sole

of the foot, it divides into the medial and lateral plantar nerves,

which supply motor power to the small muscles of the foot and sensation

to the sole (see Fig. 12-55).

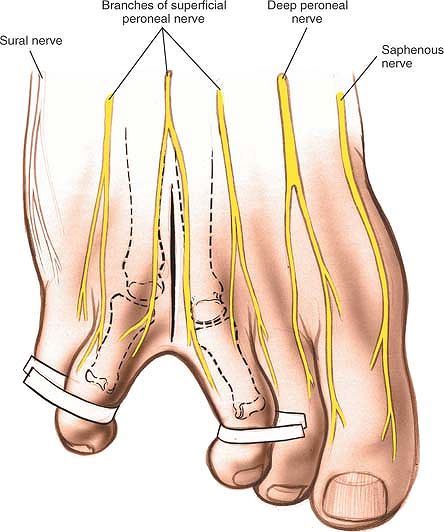

superficially, all supplying the dorsum of the foot. Knowledge of their

course is vital in planning skin incisions. The sensory supply to the

sole and heel comes from the lateral and medial plantar nerves, which

are branches of the tibial nerve that lies deep at the level of the

ankle.

-

The saphenous nerve

is the terminal branch of the femoral nerve. It runs with the long

saphenous vein in front of the medial malleolus, where it usually

divides into two branches that lie on either side of the vein and bind

closely to it. It supplies the medial, non–weight-bearing side of the

middle part and hindpart of the foot (see Fig. 12-54).P.670![]() Figure 12-56 The flexor and extensor tendons have been resected to expose the deltoid ligament of the ankle joint.

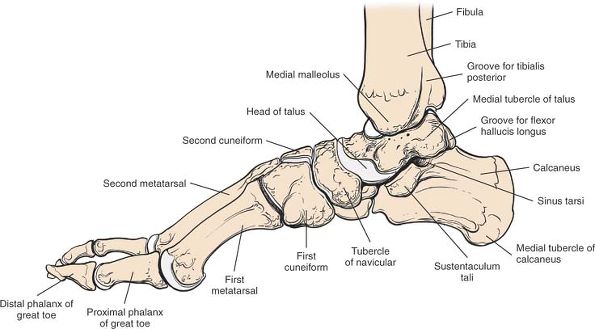

Figure 12-56 The flexor and extensor tendons have been resected to expose the deltoid ligament of the ankle joint. Figure 12-57 Osteology of the medial side of the foot and ankle.

Figure 12-57 Osteology of the medial side of the foot and ankle. -

The superficial peroneal nerve

is a terminal branch of the common peroneal nerve. It crosses the ankle

joint roughly along the anterior midline, where it usually divides into

several branches. It supplies non–weight-bearing skin on the dorsum of

the foot. The nerve is quite superficial at the level of the ankle

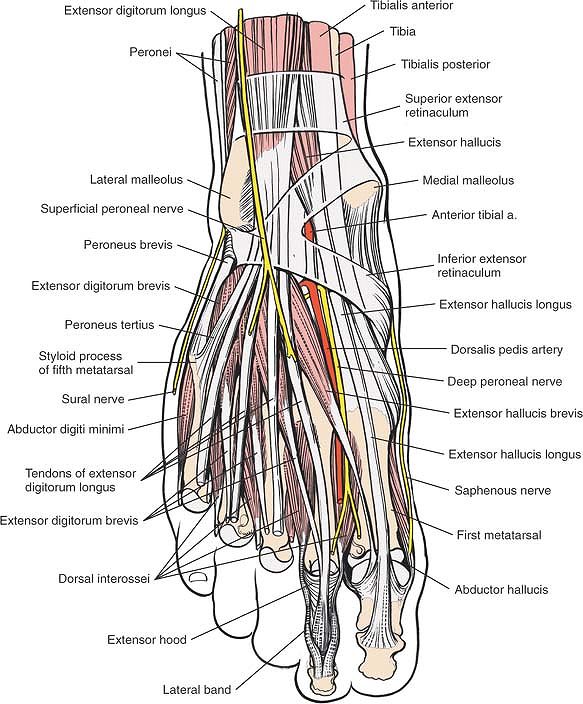

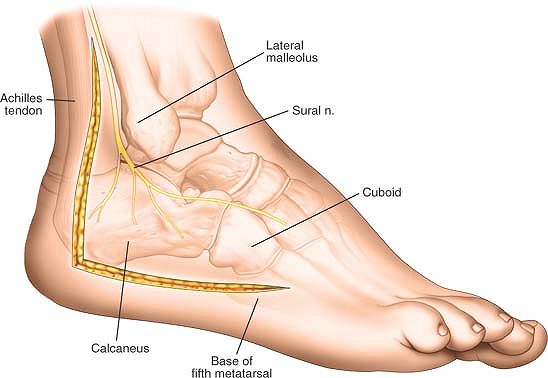

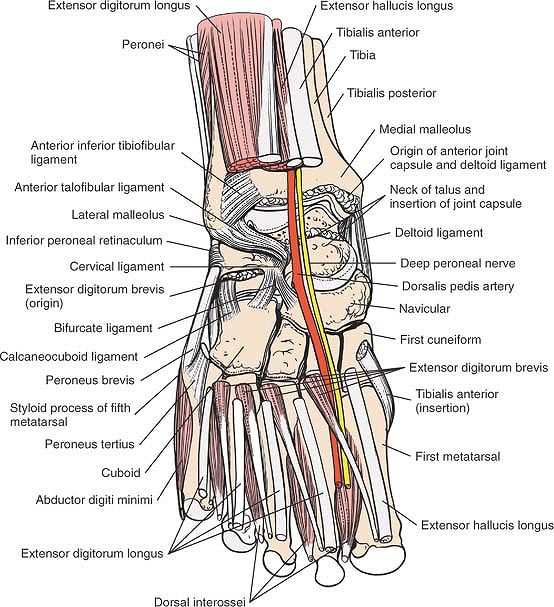

joint; great care must be taken with skin incision in its area (Fig. 12-58; see Fig. 12-78).![]() Figure 12-58

Figure 12-58

The anatomy of the superficial structures of the anterior portion of

the ankle and the dorsum of the foot. At the level of the ankle joint,

the neurovascular bundle lies immediately lateral to the extensor

hallucis longus tendon. -

The sural nerve,

a terminal branch of the tibial nerve, runs with the short saphenous

vein just behind the lateral malleolus. Similar to the saphenous nerve,

the sural nerve binds very closely to its vein; preserving the vein is

the key to preserving

P.672

the nerve during surgery. The sural nerve supplies an area of non–weight-bearing skin on the lateral side of the foot (see Fig. 12-61).

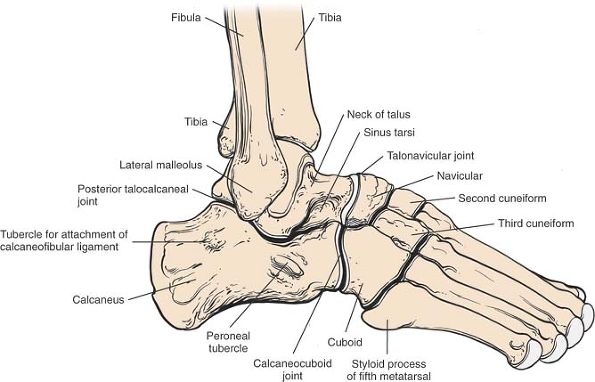

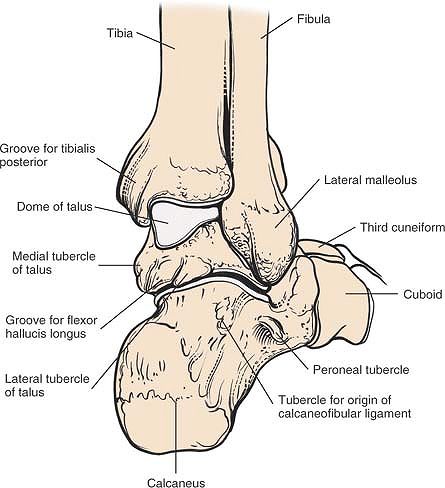

of the tibia form the articulation that bears weight in the ankle. The

joint itself is stabilized by the medial and lateral malleoli, the bony

landmarks of the area. The medial malleolus is both shorter and more

anterior. It remains in contact with the medial side of the talus

throughout the range of motion (see Fig. 12-57).

|

|

Figure 12-59

The extensor tendons have been resected to reveal the ligaments of the anterior portion of the ankle joint and the joints of the middle part of the foot. |

mortise to point 15° laterally. During dorsiflexion, the widest portion

of the talus (the anterior portion) is the ankle mortise, forcing the

mortise itself to widen. The mortise narrows to accommodate the

narrower part of the talus during plantar flexion. Hence, if an ankle

must be immobilized, it must be put in the functional position, that

is, dorsiflexion (Figs. 12-63; see Figs. 12-57 and 12-60, and 12-66).

Note also that, if a screw is inserted between the fibula and the tibia

(as in the reconstruction of a diastasis), then that screw should be

inserted with the ankle placed in maximal dorsiflexion.

|

|

Figure 12-60 Osteology of the anterior part of the ankle joint and middle part of the foot.

|

|

|

Figure 12-61

The superficial anatomy of the lateral and dorsolateral aspects of the foot and ankle. The peroneal tendons are held in place by their superior and inferior retinacula. |

|

|

Figure 12-62

The peroneal and extensor tendons have been resected to reveal the ligaments of the lateral and anterolateral ankle joint. Note the peroneal tubercle and the resected portion of the inferior peroneal retinaculum, which forms separate fibroosseous tunnels for the peroneal tendons. The calcaneofibular ligament is visible deep to the superior peroneal retinaculum. |

-

Three plantar flexors of the ankle and

foot insert into the plantar surface of the foot and are supplied by

the tibial nerve. Their positions behind the medial malleolus are

remembered best in the form of the mnemonic “Tom, Dick, and Harry.” The

tibialis posterior is closest to the medial malleolus; the flexor digitorum longus is behind it; and the flexor hallucis

longus is the most posterior and lateral of the three. A second

mnemonic, “Timothy Doth Vex Nervous Housemaids,” is older; it points

out that the posterior tibial vessels and tibial nerve lie between the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus muscles (see Figs. 12-54 and 12-55). -

The three muscles that insert into the

posterosuperior part of the os calcis (the gastrocnemius, soleus, and

plantaris) do so via their common Achilles tendon. Supplied by the

tibial nerve, they are the most powerful plantar flexors of the ankle.

Because they insert more to the medial side of the posterior surface of

the calcaneus than to the lateral side, they also invert the heel.

posterior surface of the calcaneus. The collagen fibers that comprise

the tendon rotate about 90° around its longitudinal axis, between its

origin and its insertion onto bone. Viewed from behind, the rotation is

in a medial to lateral direction. Thus,

fibers

that begin on the medial side of the tendon lie posteriorly, and those

that begin on the lateral side lie anteriorly at the level of the

insertion. This anatomic fact makes it possible to lengthen the

Achilles tendon by dividing its anterior two thirds near the insertion

and its medial two-thirds 5 cm more proximally. Dorsiflexion of the

foot lengthens the tendon, and no suture is required. The operation can

be done either as an open or as a subcutaneous procedure.5

This arrangement of the fibers can be remembered by thinking of this

tendon lengthening as the “DAMP operation,” which stands for distal anterior medial proximal.

|

|

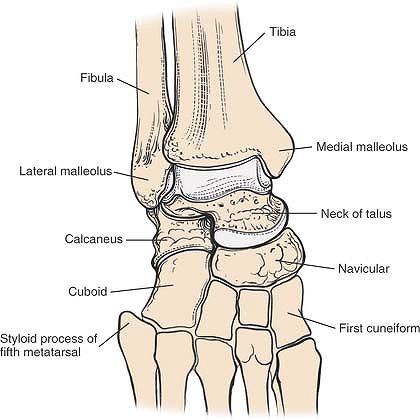

Figure 12-63 Osteology of the lateral side of the foot and ankle.

|

with a bursa that may become inflamed. A second bursa exists between

the insertion of the tendon into the os calcis and the skin (see Fig. 12-54).

thickening of the fascia that stretches from the medial malleolus to

the back of the calcaneus. It covers the three flexor tendons that pass

around the back of the tibial malleolus, as well as the neurovascular

bundle.

producing pain and paresthesia in the distribution of the medial and

lateral plantar nerves and their calcaneal branches. The syndrome is

known as the tarsal tunnel syndrome (see Fig. 12-54).

joint. All are extensors of the ankle and are supplied by the deep

peroneal nerve. The muscles, from medial to lateral, are the tibialis

anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and

peroneus tertius. The neurovascular bundle crosses the front of the

ankle virtually under the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus (see Fig. 12-58).

is a thickening of the deep fascia above the ankle. It runs between the

tibia and the fibula, and is split by the tendon of the tibialis

anterior muscle, which lies in a synovial sheath just above the ankle

(see Fig. 12-58).

on the dorsum of the foot, is attached to the lateral side of the upper

surface of the os calcis. The retinaculum is split medially; the upper

part attaches to the medial malleolus, whereas the lower part travels

across the foot, where it sometimes joins the plantar aponeurosis in

the sole. The two retinacula prevent the anterior tendons from

bowstringing; they should be repaired after any approach that cuts them

(see Fig. 12-58).

pass behind the lateral malleolus to reach the foot. Both evert the

foot and are supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve (see Fig. 12-61).

behind the lateral malleolus, often is used in reconstruction of the

lateral ligaments of the ankle. In cases of instability, maintain the

distal insertion of the tendon intact; the proximal portion of the

tendon is detached surgically, threaded through the fibula, and

attached to the talus, calcaneus, or itself to substitute for the

damaged ligaments. The peroneus brevis is recognizable both by its

position immediately behind the lateral malleolus and by its

muscularity almost down to the level of the ankle joint.

as they pass around the back of the lateral malleolus. The sheath

encloses both tendons down to the peroneal tubercle. At this point,

each tendon gains its own separate sheath (see Figs. 12-61 and 12-62). This also is the site of peroneal tendinitis, which commonly occurs in joggers.

confined almost exclusively to three joints: the posterior part of the

subtalar joint, the talocalcaneonavicular joint, and the calcaneocuboid

joint. The anatomy of the approaches is the anatomy of the joints

themselves, because they all are superficial structures (see Figs. 12-63 and 12-66).

obliquely across the foot, between the talus and the calcaneus. The

canal is formed by two grooves, one on the inferior surface of the

talus and the other on the superior surface of the calcaneus. The canal

separates the talocalcaneonavicular joint from the talocalcaneal joint

and acts as a landmark for surgical access to the two joints. At its

lateral end, the canal widens considerably into the sinus tarsi.

ligamentum cervicis tali, and a large fat pad; the ligament must be

divided and the fat pad mobilized for access to the sinus and joints.

The extensor digitorum brevis muscle originates from the top of the

anterior wall of the sinus. It must be detached for access to the

calcaneocuboid joint.

subtalar joint, which consists of a convex superior facet of the talus

and a concave facet of the talus. The joint line is oblique when viewed

from the lateral (operative) side. To see it better, the peroneal

tendons that overlie it partially must be mobilized and retracted

anteriorly.

subtalar joint, the talocalcaneonavicular joint. This complex joint

consists of a ball (the head of the talus) articulating with a socket

(the concave posterior aspect of the navicular, the concave anterior

end of the superior surface of the calcaneus, and the spring

ligament—short plantar calcaneonavicular ligament—that connects the two

bony elements of the socket). From the lateral side, the talonavicular

part of the joint appears nearly vertical. From a dorsal point of view,

the joint runs transversely across the foot, in line with the

calcaneocuboid joint.

formed by the anterior end of the calcaneus and the posterior aspect of

the cuboid. From the lateral side, the joint looks vertical. A more

dorsal view shows that it runs transversely across the foot in line

with the talonavicular joint.

become accessible if surgery remains on bone and the surgeon is aware

of the different planes of the joints.

|

|

Figure 12-64

Superficial anatomy of the posterolateral aspect of the foot and ankle. Note that the muscle fibers of the peroneus brevis run all the way to the ankle joint and lie immediately posterior to the lateral malleolus. |

|

|

Figure 12-65

The Achilles tendon and the peroneus muscles have been resected to reveal the posterolateral aspect of the ankle joint and the deep flexor tendons of the foot. The flexor hallucis longus is immediately medial to the peroneus brevis. The fascia investing these muscles is deep to the deep fascia; it separates them into peroneal and deep flexor compartments. The flexor hallucis longus remains muscular down to the ankle joint. |

|

|

Figure 12-66 Osteology of the posterolateral aspect of the foot and ankle.

|

calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joints to the tarsometatarsal

Lisfranc’s joints. All these bones and joints are superficial and can

be approached directly by dorsal, medial, lateral, and plantar

approaches. Operations in this area (which are performed rarely)

usually involve surgery on the insertions of the four powerful muscles

that, together, are responsible for controlling inversion and eversion

of the foot. These muscles are the tibialis anterior, which inserts

into the medial surface and undersurface of the medial cuneiform bone,

and into the adjoining part of the base of the first metatarsal bone;

the peroneus longus, which inserts into the lateral side of the medial

cuneiform bone; the peroneus brevis, which inserts into the base of the

lateral side of the metatarsal bone; and the tibialis posterior, which

inserts into the tuberosity of the navicular bone, the inferior surface

of the medial cuneiform bone, the intermediate cuneiform bone, and the

bases of the second, third, and fourth metatarsal bones (see Figs. 12-55, 12-58, and 12-62).

specialized procedures for the treatment of muscle imbalance, mobile

flatfoot, and an accessory navicular bone. It also is approached for

open reduction and internal fixation of fractures in and around

Lisfranc’s joint, and for local tarsal fusion. Only the general

surgical approaches are considered here, because the details of

operative technique and indications are beyond the scope of this book.

Dorsomedial approaches and medial approaches are carried out with the

leg in its natural position of slight external rotation, whereas

dorsolateral approaches require internal rotation of the limb, which is

achieved by placing a sandbag under the buttock. For

all

procedures, exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 3 to 5

minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage. Then, inflate a

tourniquet (see Fig. 12-31).

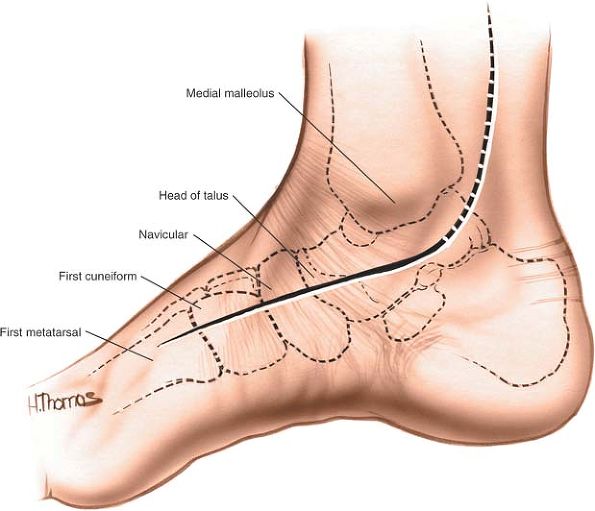

feel along the medial border of the foot in a distal to proximal

direction. The first metatarsal flares slightly at its base to meet the

first cuneiform.

is immediately proximal to the navicular. It can be located by

inverting and everting the forepart of the foot. The motion that occurs

between the talus and the navicular is palpable (Fig. 12-67).

|

|

Figure 12-67

Incision for exposure of the middle part of the foot. Make a longitudinal incision directly over the area to be exposed. A dorsomedial incision exposes the talonavicular joint, the navicular-medial cuneiform joint, and the first metatarsocuneiform joint. |

by feeling along the lateral side of its shaft in a distal to proximal

direction until its flared base is reached; this is the styloid

process, into which the peroneus brevis muscle inserts (Fig. 12-69).

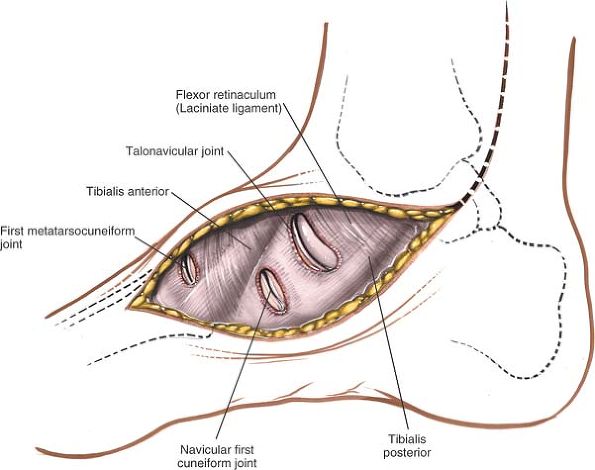

incision to expose the talonavicular joint, the navicular-medial

cuneiform joint, and the first metatarsocuneiform joint, and to reveal

the insertions of the tendons of the tibialis anterior and tibialis

posterior muscles (see Fig. 12-67). Use a dorsolateral incision to expose the calcaneocuboid joint and the base of the fifth metatarsal (see Figs. 12-63 and 12-69).

|

|

Figure 12-68

Develop the skin flaps. Note the insertions of the tibialis anterior and posterior muscles. Incise the joint capsules of the talonavicular joint, the navicular-medial cuneiform joint, and the first metatarsocuneiform joint according to the demands of the surgery. |

|

|

Figure 12-69 A dorsolateral incision exposes the calcaneocuboid joint and the base of the fifth metatarsal.

|

tarsus is required, it is better to make two separate longitudinal

incisions centered over the structures to be explored. Separate

incisions nearly always are required for the open reduction of

fractures of Lisfranc’s joint.

Longitudinal incisions avoid damaging cutaneous nerves. Certain major

reconstructive operations, such as wedge tarsectomy, necessarily cut

cutaneous nerves, leaving portions of the dorsum of the foot partially

anesthetic.

|

|

Figure 12-70

Develop the skin flaps on the lateral side of the middle part of the foot. Note the tendon of the peroneus brevis as it inserts into the base of the fifth metatarsal. The joint capsule of the calcaneocuboid joint can be incised, if necessary. |

exposed, taking care to avoid any cutaneous nerves that can be

identified. Try to make sure that skin flaps are as thick as possible;

minimize retraction as much as possible. The structures of the dorsum

of the foot nearly all are subcutaneous. Take care to avoid damaging

the insertions of the four powerful invertors and evertors of the foot (Figs. 12-68 and 12-70).

malleolus; this exposes not only the lateral side of the ankle joint,

but also the posterior part of the subtalar joint and the

calcaneocuboid joint. (See sections describing the posterolateral approach to the ankle and lateral approach to the hindpart of the foot.)

the incision up behind the medial malleolus, curving it to a point

midway between the medial malleolus and the Achilles tendon. This

extension exposes those structures that pass around the back of the

medial malleolus. It is used commonly in the treatment of clubfoot, but

its safety is controversial; the neurovascular bundle must be

protected. (See the section regarding the posteromedial approach to the

ankle.)

surgery on the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe for the

treatment of bunions or hallux rigidus. Their uses include the

following:

-

Excision of the metatarsal head6

-

Excision of the proximal part of the proximal phalanx7

-

Excision of metatarsal exostosis (bunionectomy)

-

Distal metatarsal osteotomy8,9

-

Soft-tissue correction of hallux valgus, including reefing procedures, tenotomies, and muscle reattachments10

-

Arthrodesis of the metatarsophalangeal joint11

-

Insertion of joint replacements

-

Dorsal wedge osteotomy of the proximal phalanx in cases of hallux rigidus12

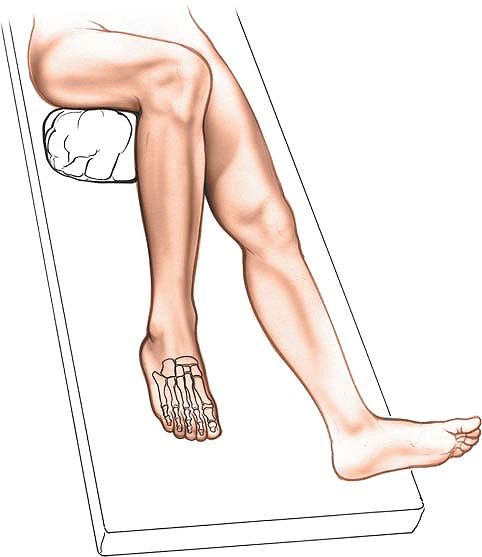

exsanguination, use a tourniquet placed on the middle of the thigh.

Alternatively, use a soft rubber bandage to exsanguinate the foot, and

then wrap the leg tightly just above the ankle (see Fig. 12-1).

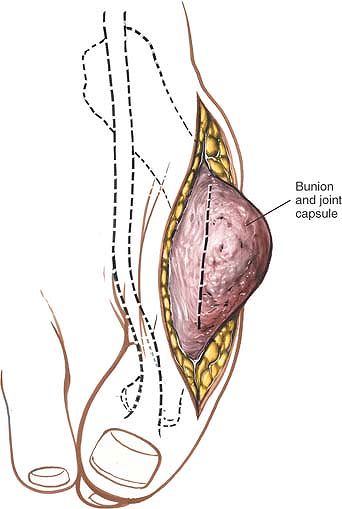

dorsomedial skin incision provides access to the exostosis on the

metatarsal head without much skin retraction; it is by far the most

commonly performed incision. It does have drawbacks, however. The bursa

covering the exostosis may have become inflamed, complicating the

surgery, and the skin on the medial aspect of the metatarsophalangeal

joint is thinner than on the dorsum of the joint and may not heal as

well.

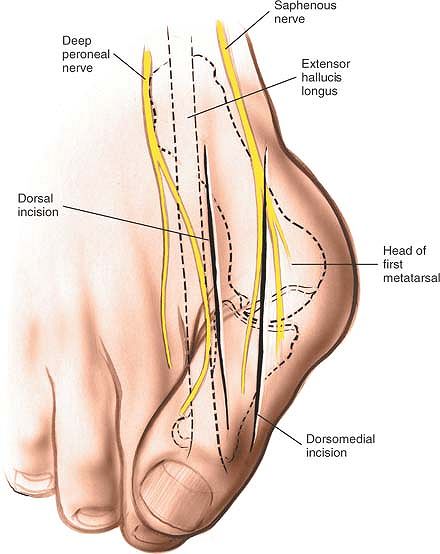

interphalangeal joint on the dorsomedial aspect of the great toe. Curve

it over the dorsal aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joint, remaining

medial to the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus muscle. Then,

curve the incision back by cutting along the medial aspect of the shaft

of the first metatarsal, finishing some 2 to 3 cm from the

metatarsophalangeal joint (Fig. 12-71).

dorsal incision just proximal to the interphalangeal joint and just

medial to the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus muscle. Extend the

incision proximally, parallel, and just medial to the tendon of the

extensor hallucis longus. Finish about 2 to 3 cm proximal to the

metatarsophalangeal joint. Note that the final incision is straight (Fig. 12-74).

subcutaneous; the two tendons close to the dissection, the extensor

hallucis longus and the abductor hallucis, receive their nerve supplies

proximal to this approach and cannot be denervated by it.

|

|

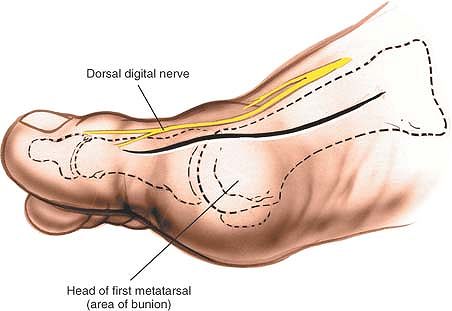

Figure 12-71

Dorsomedial skin incision for the medial approach to the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. Note the proximity of the dorsal digital nerve to the incision. |

|

|

Figure 12-72 Incise the deep fascia. Develop a joint capsule flap. Protect the dorsal digital branch of the medial cutaneous nerve.

|

|

|

Figure 12-73 Make a U-shaped incision into the joint capsule, leaving the capsule attached to the proximal end of the proximal phalanx.

|

|

|

Figure 12-74

Dorsal incision for the approach to the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe. Note that the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus is displaced laterally and that the sensory nerve to the medial aspect of the great toe runs parallel to the incision. Note that the great toe is framed by branches of the saphenous nerve medially and the deep peroneal nerve laterally. |

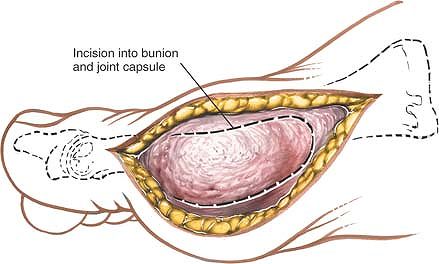

cut down to the dorsomedial aspect of the metatarsophalangeal joint.

The dorsal digital branch of the medial cutaneous nerve, which often is

visible, is retracted laterally with the skin flap on the lateral edge

of the wound. Make a U-shaped incision into the joint capsule, leaving

the capsule attached to the proximal end of the proximal phalanx (Figs. 12-72 and 12-73).

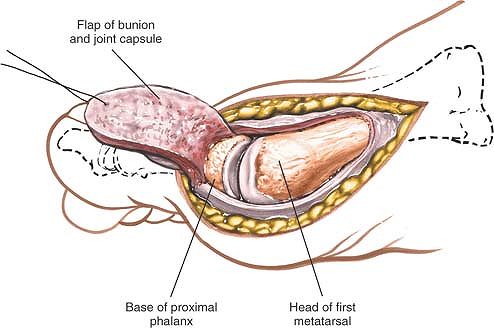

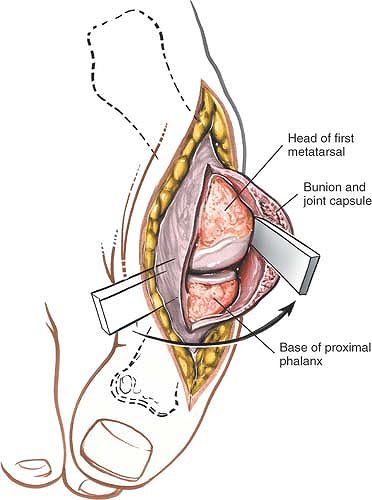

retract the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus muscle laterally. To

enter the joint, incise the dorsal aspect of the joint capsule. Note

that the type and position of the capsulotomy depend on the procedure

to be performed (Figs. 12-75 and 12-76).

proximal phalanx and first metatarsal bones longitudinally. Using blunt

instruments, strip the coverings off the bones, taking care not to

damage the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus muscle, which lies in a

fibro-osseous tunnel on the plantar surface of the proximal phalanx,

between the sesamoid bones. The extent of the deep dissection depends

on the procedure to be carried out. Strip only a minimum of periosteum

off the bone. Do not strip all the soft-tissue attachments off the

metatarsus if a distal osteotomy of that bone is to be performed,

because the metatarsal head is rendered avascular by stripping.

should not be cut during the approach. Indeed, in cases of bunion, the

tendon bowstrings laterally across the metatarsophalangeal joint and is

even more lateral to the incision than usual. Protect the dorsal

digital nerve if it can be seen along the line of the incision (see Figs. 12-71 and 12-74).

|

|

Figure 12-75

Develop the skin flaps. Divide the deep fascia in line with the skin incision, and retract the tendon of the extensor hallucis longus laterally. |

muscle is vulnerable as the base of the proximal phalanx is stripped.

The tendon lies in a groove on the plantar surface of the proximal

phalanx so close to the periosteum that, if care is not taken, it may

be damaged during stripping. The tendon often is displaced laterally in

patients with hallux valgus (see Fig. 12-54).

|

|

Figure 12-76 Incise the joint capsule dorsally, and remove as much of the capsule as necessary depending on the procedure to be performed.

|

the bones provides an adequate view of the joint. The approach cannot

be extended usefully to other joints in the foot, but may be extended

proximally for access to the shaft of the metatarsus.

metatarsophalangeal joints of the second, third, fourth, and fifth

toes, avoids incision of the plantar skin of the foot. Most plantar

approaches scar the weight-bearing skin, violating a basic surgical

principle.

-

Excision of metatarsal heads

-

Distal metatarsal osteotomy

-

Partial proximal phalangectomy

-

Fusion of metatarsophalangeal joints (rare)

-

Capsulotomy of metatarsophalangeal joints

-

Muscle tenotomy

-

Neurectomy

|

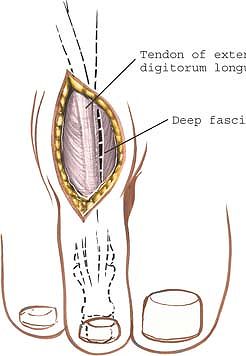

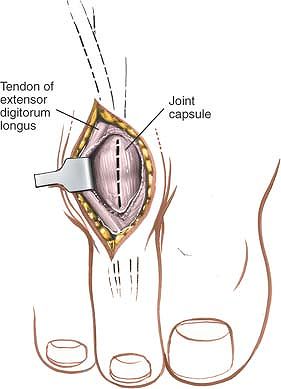

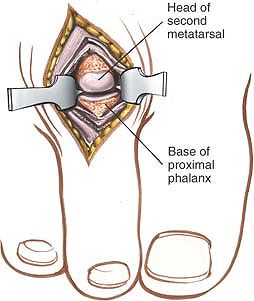

|