Miscellaneous Conditions

II – Knee > Part B – Evaluation and Treatment of Knee Disorders >

21 – Miscellaneous Conditions

the vast majority of knee degeneration. A handful of other conditions,

however, can lead to significant morbidity. It is important for the

physician to be familiar with these less common entities to avoid

diagnostic pitfalls and to provide appropriate care. Although this

review stresses the orthopedic issues in caring for these patients,

treating these conditions often is best accomplished with coordinated

input from different specialties. These conditions (Table 21-1)

are a heterogeneous group with various causes. Although they are

uncommon, it is useful to be aware of the key features of these

conditions when evaluating a patient with knee complaints.

entities. The exact mechanism for development of this condition remains

elusive. An area of the involved bone sustains an ischemic insult that

initiates a process of remodeling and collapse. Depending on the

location and extent of this collapse, articular surface incongruity

leads to joint degeneration. Spontaneous osteonecrosis usually develops

in older patients (sixth or seventh decade) without any antecedent

trauma or other known risk factor. Younger patients also may develop

knee osteonecrosis, usually in association with trauma or other known

risk factors such as alcohol consumption or corticosteroid use.

which articular (hyaline) cartilage is produced in the soft tissues

around joints. These cartilaginous areas can then break free and become

loose bodies. Patients develop locking, catching, and other mechanical

symptoms based on the size and number of these cartilaginous lesions.

As a consequence of intra-articular loose bodies, patients develop

secondary degenerative changes. Most cases are monoarticular, with the

knee joint involved most commonly. Men are approximately two times more

likely than women to develop this disorder.

chondromatosis is an exceedingly rare phenomenon. If imaging or

clinical findings raise even the possibility of malignancy, it is

appropriate to refer the patient to an orthopedic oncologist for

further management.

recurrent intra-articular hemorrhages in patients with clotting factor

deficiencies. Hemophiliac arthropathy therefore begins with

intra-articular bleeding. Reaction to intra-articular blood leads to

varying degrees of synovitis. This inflamed synovium is then more

susceptible to further intra-articular bleeds, setting up a potential

cycle in which patients have recurrent hemarthroses. The extensive

chronic synovitis that ensues eventually leads to joint erosions and,

over time, end-stage arthropathy.

proliferative condition of synovium in which there is an accumulation

of giant cells and hemosiderin. PVNS does not have malignant potential

but can be locally aggressive, leading to considerable synovitis that

produces erosions and secondary degenerative changes. The knee joint is

most commonly involved and, as in synovial chondromatosis, most cases

are monoarticular. PVNS is a synovial disease but also can involve

periarticular sites such as tendon sheaths and bursae.

intra-articular reactions to the characteristic crystals of the two

conditions. The body mounts an inflammatory response to the crystals,

thereby leading to secondary joint inflammation and eventually

degeneration. Patients with calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease

(CPPD), or pseudogout, may have a spectrum of findings from acute

synovitis to a long-standing arthropathy with secondary degenerative

changes. These patients also can develop deposits in hyaline

and

meniscal cartilage. Gout is caused by symptomatic elevation of uric

acid, also leading to an inflammatory response to crystals. A

combination of dietary factors and medicines—especially thiazide

diuretics—can precipitate gouty flares.

|

TABLE 21-1 Less Common Causes of Knee Degenerative Joint Disease

|

|

|---|---|

|

patients begins with a careful history. The orthopedist should inquire

about onset and duration of symptoms, any antecedent of inciting

events, other joints involved, and systemic conditions for which the

patient requires medical treatment. Patients with hemophilia should be

asked about the number of prior intra-articular bleeds.

should include surface appearance, limb alignment, range of motion,

tenderness, instability, presence of effusion, and a thorough

neurovascular exam.

diagnostically useful and give considerable, albeit temporary,

symptomatic relief. Synovial fluid in gout and pseudogout will show

characteristic crystals under the microscope: Uric acid crystals will

be negatively birefringent, and calcium pyrophosphate crystals will be

positively birefringent. As some laboratories do not routinely examine

body fluid for crystals, it is important to specify this request on the

order. Synovial fluid may be bloody in patients with PVNS, but a

nonbloody tap does not necessarily exclude this diagnosis. Synovial

fluid should also be sent for further laboratory investigations

including cell count and, when warranted, Gram stain and culture.

having already had an MRI or other advanced cross-sectional imaging,

the accepted first step in radiographic evaluation should be orthogonal

plain x-ray films. In addition to these films, additional radiographs

may be useful. A standing anteroposterior (AP) view of both knees

affords the opportunity to evaluate the contralateral joint. A patellar

view is useful for evaluating the patellofemoral articulation. In

addition to the usual radiographic stigmata of joint degeneration,

films should be scrutinized for loose bodies, radiolucent bony changes,

effusions, and changes in the soft tissues. As noted in other chapters,

concerns about limb alignment should be addressed by long-leg films

that include the hip and ankle.

radiographic manifestations of knee degeneration, the conditions in

this chapter often require ancillary studies such as bone scan or

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As with all medical tests, advanced

imaging should be ordered to answer a specific question that will guide

diagnosis or treatment. MRI is also useful in the face of unusual or

unexpected findings on plain films, such as radiolucent changes on both

the tibial and femoral sides of the knee joint. Magnetic resonance

imaging is clearly superior to plain films for evaluating soft tissues,

bone marrow, and articular cartilage. Computed tomography (CT) scanning

is not usually indicated or helpful in the conditions outlined here.

Although orthopedists are increasingly comfortable with different

imaging modalities, a radiologist with specialized musculoskeletal

training is invaluable in choosing which imaging studies are most

appropriate and also in the subsequent interpretation of these studies.

difficult, especially in early stages. Plain films may be negative

initially. Traditionally, bone scans have been used for diagnosis. More

recent reports show a high sensitivity for MRI. Moreover, MRI is useful

in characterizing the exact location and extent of bony and

cartilaginous involvement. The classic location of knee osteonecrosis

is the medial femoral condyle, but the lateral condyle and proximal

tibia also may be involved.

As these bodies contain varying amounts of mineral, not all will

necessarily show up on plain films. MRI is useful in these cases to see

the extent and number of loose bodies. As with PVNS, the location and

extent of disease as characterized on MRI helps the surgeon plan the

appropriate operative treatment.

including joint erosions that may appear on both sides of a joint.

Occasionally, one may appreciate a soft tissue mass or large effusion

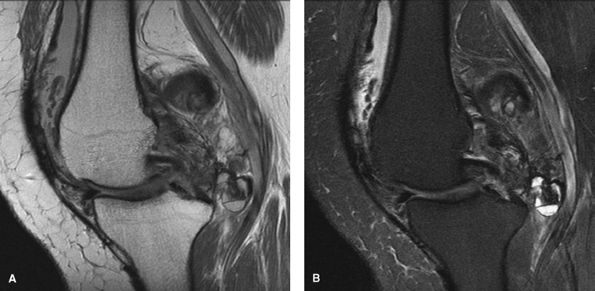

on plain film (Fig. 21-2). Because PVNS is a soft tissue process, MRI is the best imaging method to gauge the extent of disease (Fig. 21-3). MRI is extremely useful in preparing an appropriate treatment plan for PVNS of the knee.

Radiographic manifestations include calcifications of the articular

cartilage and the meniscus. Unless one suspects a superimposed meniscal

tear or other intra-articular pathology, MRI is not indicated as part

of the workup of CPPD.

|

|

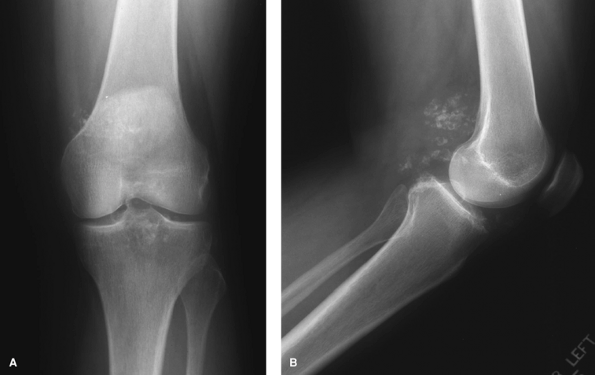

Figure 21-1 Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) knee x-ray views showing mineralized cartilaginous areas consistent with synovial chondromatosis.

|

|

|

Figure 21-2

Lateral knee radiograph in a patient with pigmented villonodular synovitis. Note the considerable soft tissue mass posteriorly and the absence of significant osseous abnormalities. |

including symptom modification and anti-inflammatory medication.

Surgical management is indicated when nonoperative methods no longer

benefit the patient.

patients with hemophilia. Avoiding trauma and closely following

clotting factor levels are two straightforward ways to minimize the

number of intra-articular bleeds. Patients with recent bleeds also may

benefit from a brief period of joint immobilization to allow time for

soft tissues to recover. Because patients with hemophilic arthropathy

tend to develop soft tissue contractures, however, immobilization

should be used judiciously.

centers where the surgeon is supported by an active medical hemophilia

program. Hemophiliacs undergoing invasive procedures should be screened

for clotting factor inhibitors.

potentially dangerous, but also consumes considerable resources,

including the time and energy of consulting services and laboratory

surveillance of factor and inhibitor levels. For this reason, P-32

radiation synovectomy is attracting increasing interest in the

treatment of early arthropathy. Radiation synovectomy is especially

appropriate in patients without significant joint degeneration.

Although it obviously cannot reverse existing articular damage, the

procedure can help break the vicious and destructive cycle of synovial

irritation and intra-articular hemorrhage.

|

|

Figure 21-3 Proton density (A) and T2 (B) magnetic resonance images of the same knee as Figure 21-2 showing extensive pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS).

|

Anti-inflammatory medicines and colchicine are useful in acute flares.

For long-term control of high blood uric acid levels, patients should

be managed in conjunction with colleagues

in internal medicine. Pharmacologic treatment (allopurinol) in combination with dietary modifications is recommended.

first. However, symptoms frequently persist and operative treatment,

usually with arthroplasty, commonly is needed.

amenable to nonsurgical treatment. The natural history of PVNS,

especially the diffuse form, is progressive joint erosions and

arthropathy. As with hemophiliac arthropathy, there is some interest in

using radioactive synovectomy in these patients. Although synovial

chondromatosis typically is considered to be less aggressive and

self-limiting, the loose bodies of this condition often cause pain,

loss of function, and eventually secondary joint degeneration.

managed with open synovectomies. Current trends favor the use of

arthroscopic treatment. These procedures require less clotting factor

support and are less morbid than open surgical approaches.

on several issues, including the amount of pain and desired level of

function and activity. These patients can have compromised bone stock,

distorted osseous architecture, and severe soft tissue contractures

from superimposed arthrofibrosis. In spite of these potential

difficulties, outcomes of knee replacements in this population may be

favorable, but are associated with a higher rate of infection.

choice for synovial chondromatosis. When possible, arthroscopic

procedures allow the surgeon to remove synovium and loose bodies while

avoiding the morbidity of an open approach. Occasionally, extensive

disease and difficult location require open synovectomy and

debridement. Because patients with these conditions often begin with

decreased range of motion, an early and closely supervised physical

therapy program is essential postoperatively.

usually is favorable. Some patients develop recurrent disease, but the

natural history commonly involves regression of disease. Patients may

develop secondary arthritis from loose bodies and may require joint

replacement.

nonoperative care to osteotomies, condylar allografts, and joint

replacement. Core decompression and arthroscopic debridement also have

been recommended with varying rates of success. The main determinants

of treatment choice include the location of the lesion, the amount of

joint involvement, the extent of secondary degenerative changes,

overall limb alignment, and patient age. Historically, outcomes of knee

replacement in osteonecrosis have not been as successful as in other

conditions. More recent reports have been more encouraging, however.

self-limiting course over time, diffuse PVNS is locally aggressive.

Inadequate removal of involved synovium can lead to recurrent disease;

local recurrence rates are reported as high as 50% in the literature.

Localized nodular forms of PVNS may be amenable to arthroscopic

removal, but diffuse PVNS should be treated with an open total

synovectomy. For patients with advanced degenerative changes, treatment

options are nonoperative management versus total joint replacement.

Knee fusion has fallen out of favor and should be considered a salvage

procedure.

In patients with long-standing disease and extensive surface damage,

total knee arthroplasty may be indicated with an expectation of success

equal to that for osteoarthritis.

Patients with gout should continue their preoperative medical regimen to prevent flares in other joints.

the principles of postoperative care outlined in previous chapters.

Coordinated multispecialty input often is in the patient’s best

interest. Patients with long-standing adrenal suppression from oral

corticosteroids may need perioperative stress dosing. Hemophiliacs

obviously must have appropriately titrated clotting factor levels and

perioperative input from a hematology service. These patients need

clotting factor support for several weeks following the procedure as

they embark on a therapy program. Again, close collaboration with

colleagues in internal medicine is essential for appropriate

perioperative care.

synovectomies, early institution of a physical therapy program is

critical. Patients with synovial chondromatosis and PVNS can be

affected by a vicious cycle of decreased motion that is further

compromised by open and extensive surgery around the involved joint.

These patients should receive particularly close attention from

therapists and begin working on range of motion as soon as the

periarticular soft tissues allow. Hemophiliacs often have considerable

preoperative flexion contractures and they, also, should have

especially close follow-up with therapy.

diagnoses discussed above can be treated with reasonable expectations

of success if one is aware of the potential difficulties in diagnosis

and treatment. Multispecialty care is important and can minimize

morbidity and perioperative complications.