CHAPTER 31 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 31 – Patient Positioning and Portal Placement

Bradley D. Dresher, MD

As advances in technology and technique allow better visualization and navigation of the elbow joint, indications for elbow arthroscopy are expanding. Descriptions of new portals, instrumentation, and techniques are frequent in the literature and continue to increase the use of the arthroscope for diagnosis and treatment of a number of elbow injuries and disorders. A thorough understanding of portal placement and normal arthroscopic anatomy is essential for use of the arthroscope in the elbow joint to be mastered and for complications to be avoided.

A comprehensive history discerns whether a single traumatic event or repetitive traumatic episodes occurred before the onset of symptoms. The circumstances under which symptoms occur and whether they are related to activities of daily living, occupational activities, or athletic activities are noted.

All three elbow compartments (medial, lateral, posterior) are carefully examined. Elbow stability, range of motion, and neurovascular status are evaluated.

| • | Flexion, extension, pronation, and supination are determined and compared with the opposite extremity. |

Review carefully for fractures, subluxation, dislocation, degenerative changes, osteophytes, and loose bodies.

Indications and Contraindications

Common indications include removal of loose bodies, resection of symptomatic plicae, capsular release in patients with contracture, removal of osteophytes, synovectomy in patients with inflammatory arthritis, treatment of osteochondritis dissecans, débridement for lateral epicondylitis, and treatment of some elbow fractures (Steinmann et al). The primary contraindication to elbow arthroscopy is any severe distortion of normal bone or soft tissue anatomy that jeopardizes safe entry of the arthroscope into the joint. Local soft tissue infection in the area of portal sites also is a contraindication.

We prefer to use a general anesthetic because it is reliable, provides muscle relaxation, allows positioning without discomfort to the patient, and permits the use of a tourniquet when it is needed. Local and intravenous blocks have the disadvantage of making neurovascular evaluation unreliable postoperatively.

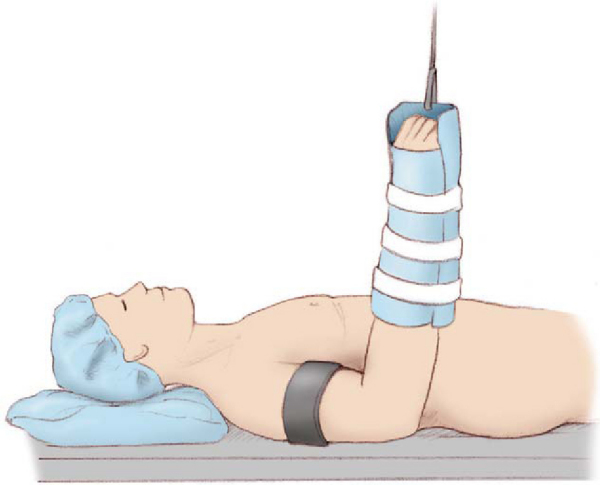

Supine Position (

Fig. 31-1

; authors’ preference)

The patient is placed supine on the operating table with the scapula at the edge of the table and the shoulder abducted 90 degrees. The operative extremity is placed in a prefabricated wrist gauntlet, stockinette, or finger traps. Enough traction is applied to suspend the elbow away from the table at 90 degrees of flexion (10 pounds is the standard amount). A well-padded tourniquet is placed high on the operative arm to allow proper portal placement and instrument manipulation. Use of a traction setup allows access for medial and lateral approaches and eliminates the need for an assistant to hold the extremity. Flexing the elbow 90 degrees relaxes the neurovascular structures, making portal placement safer, and the forearm can be supinated and pronated during the procedure.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-1 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

If a suspension device is not available, two arm boards can be used to support the operative extremity. This requires an assistant to hold the arm at 90 degrees of elbow flexion at all times. This setup is more stable but does require more operative personnel.

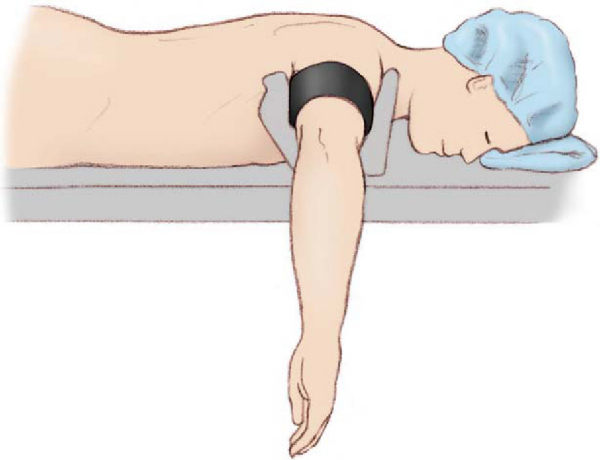

Prone Position (

Fig. 31-2

)

After intubation, the patient is placed prone, with care taken to place chest bolsters to assist in torso and airway care. The patient is then positioned near the edge of the table; with a rolled towel or arm holder, the operative extremity is positioned with the shoulder abducted 90 degrees, the elbow flexed 90 degrees, and the hand pointed toward the floor. Before the extremity is prepared, a well-padded tourniquet is placed high on the arm, and the elbow is moved through a full range of motion to ensure that complete flexion and extension can be obtained and the shoulder is not hyperextended. Baker noted several advantages of the prone position. First, because of the weight of the arm over a bolster, no traction is needed because gravity assists in joint distraction. Second, the arm is stable during the procedure, unlike in the supine position, in which the arm may tend to swing during portal placement and instrument introduction. Third, the neurovascular structures are protected by being farther away from the capsule as a result of gravity and fluid distention of the joint. Next, if it is needed, conversion to an open procedure can be done through a medial or lateral exposure. Finally, the elbow can be fully extended during the procedure if necessary.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-2 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

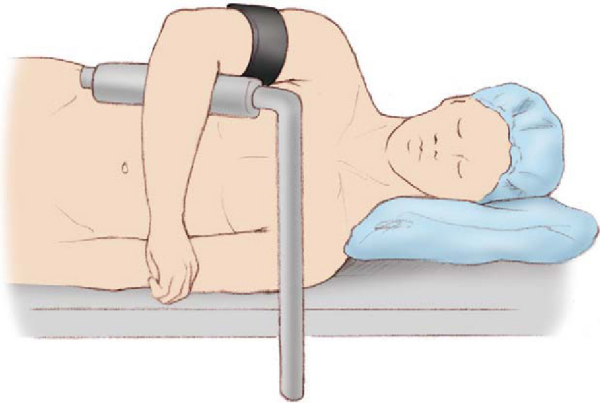

Lateral Decubitus Position (

Fig. 31-3

)

This position is similar to the prone position but allows access to the posterior compartment and also provides easy maintenance of anesthesia during the procedure. Again, a tourniquet is applied high on the arm, and the arm is positioned with a bump or bolster attached to the bed.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-3 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

General Principles of Portal Placement

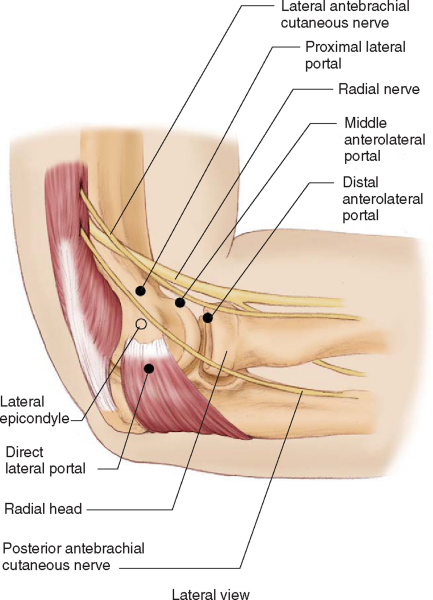

After general anesthesia has been administered, bone anatomy and landmarks are palpated and marked (

Fig. 31-4

). The radial head, found by supination and pronation of the forearm, is outlined, as are the medial and lateral epicondyles and the olecranon. The course of the ulnar nerve through the cubital tunnel also should be outlined.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-4 |

Lateral Portals (

Fig. 31-5

)

The direct lateral portal lies in the center of a triangle formed by the lateral epicondyle, radial head, and olecranon. This soft spot is easily palpated before distention. This approach passes through the anconeus muscle; it is used for initial joint distention and for lateral portal viewing. Watch for the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which passes within 7 mm.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-5 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

The anterolateral portal lies 2 to 3 cm distal and 1 to 2 cm anterior to the lateral humeral epicondyle, within the sulcus between radial head and capitellum anteriorly. These measurements may vary, depending on the size of the patient, and portal placement depends on locating the radiocapitellar articulation. The anterolateral portal passes through the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the supinator muscle before reaching the capsule. This portal provides an excellent view of the medial capsule, medial plica, coronoid process, trochlea, and coronoid fossa. Watch for the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve, an average of 2 mm from the sheath; the radial nerve, which is usually 7 to 11 mm anteromedial to the portal but may be as close as 2 or 3 mm; and the posterior interosseous nerve, 1 to 13 mm from the portal, depending on the degree of forearm pronation.

The middle anterolateral portal, located 1 cm directly anterior to the lateral epicondyle, provides access to the radiocapitellar joint and lateral compartment and is a good working portal for instrumentation. It also functions as a good viewing portal for the anterior ulnohumeral joint.

The proximal anterolateral portal is made 1 to 2 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle. Stothers et al described this portal as being safer than the middle anterolateral portal, which was safer than the standard distal anterolateral portal.

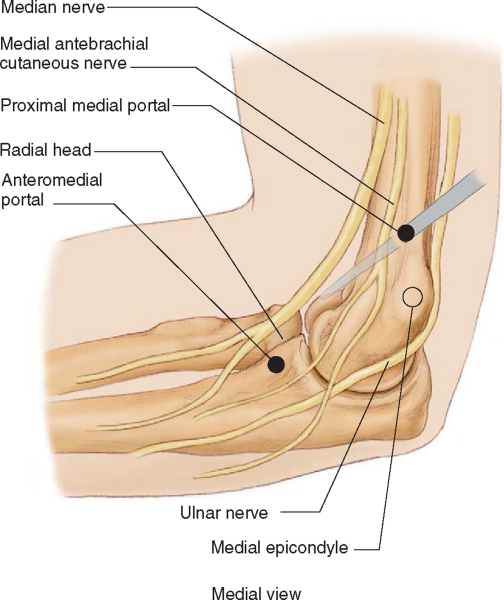

Medial Portals (

Fig. 31-6

)

The anteromedial portal is placed 2 cm anterior and 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. It is usually placed under direct visualization with the use of an 18-gauge needle. The anteromedial portal passes between the radial aspect of the flexor digitorum sublimis and the tendinous portion of the pronator teres before entering the joint capsule. It allows examination of the radiocapitellar and humeroulnar joints, the coronoid fossa, the capitellum, and the superior capsule. Watch for the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which is an average of 6 mm from the portal but may be as close as 1 mm; the median nerve, which is 19 mm anterolateral to the portal with the joint distended and 12 mm without distention; and the ulnar nerve, located an average of 21 mm from the portal. The portal lies 17 mm posteromedial to the brachial artery.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-6 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

The proximal medial (superomedial) portal is placed 1 cm anterior and 1 to 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and passes through a tendinous portion of the flexor-pronator group. This portal provides excellent viewing of the anterior compartment of the elbow, particularly the radiocapitellar joint. Watch for the median nerve, which is 22.3 mm from the portal.

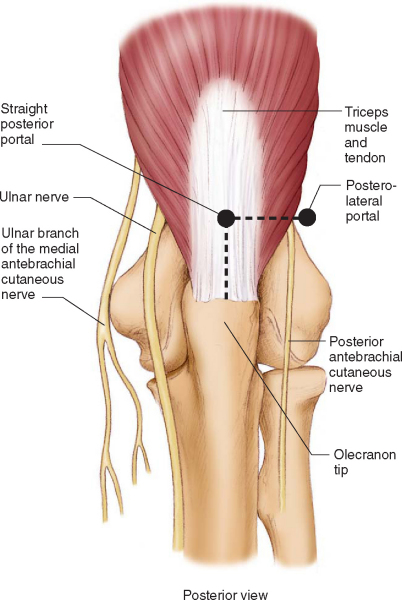

Posterior Portals (

Fig. 31-7

)

The posterolateral portal is placed 2 to 3 cm proximal to the olecranon tip and just lateral to the lateral border of the triceps muscle. This portal allows examination of the olecranon tip, olecranon fossa, and posterior trochlea.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-7 (Redrawn from Baker CL Jr, Jones GL. Current concepts. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:251-264.) |

The straight posterior portal is located over the center of the triceps tendon, 2 cm medial to the posterolateral portal and 3 cm proximal to the tip of the olecranon. This portal is helpful for removal of impinging olecranon osteophytes and loose bodies from the posterior elbow joint. Watch for the posterior and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, which lie on the lateral and medial aspects of the upper arm 23 to 25 mm medial to the straight posterior portal, and the ulnar nerve, located within 25 mm of the straight posterior portal.

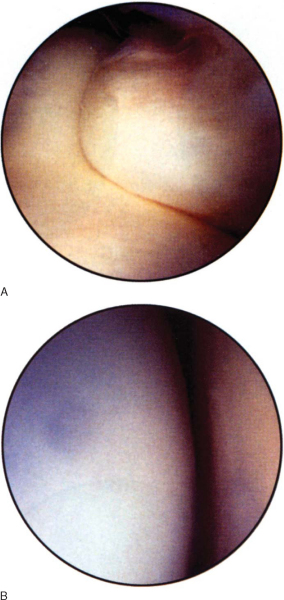

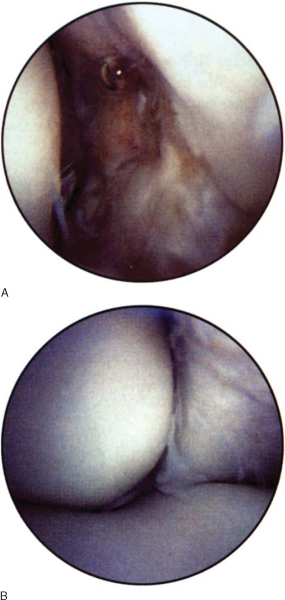

Through the anterolateral portal (

Fig. 31-8

), the coronoid and its articulation with the trochlea can be viewed. Flexion and extension of the elbow bring the anterior trochlea into view. The brachialis tendon insertion can be evaluated on the coronoid process. The coronoid fossa can be seen proximal in the compartment. With the arthroscope directed medially, the medial portion of the capsule can be examined, including the anterior third of the anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament. With proper orientation of the scope, the proximal ulna and medial gutter can be viewed. The sublime tubercle, with the intersection of the anteromedial capsule and the proximal medial ulna, can be evaluated.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-8 (From Phillips BB. Arthroscopy of upper extremity. In Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 2003.) |

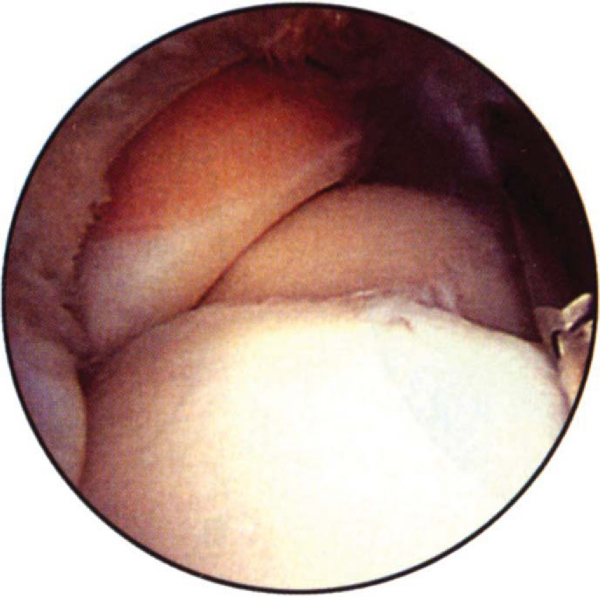

Through the anteromedial portal (

Fig. 31-9

), established under direct vision by initial placement of an 18-gauge needle, the radial head and the radiocapitellar articulation can be identified. Supination and pronation of the forearm allow viewing of 75% of the surface of the radial head. The annular ligament can be noted crossing the radial neck, and the radial fossa can be evaluated with proximal viewing of the scope. The attachment of the capsule to the humerus can be seen superiorly. The scope can then be advanced to examine the lateral gutter, the undersurface of the capsule, and the origin of the extensor muscles to the lateral epicondyle. The articulations of the radius, ulna, and distal humerus can be viewed by placing the scope between the trochlear and capitellar ridges up to the medial border of the radial head.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-9 (From Phillips BB. Arthroscopy of upper extremity. In Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 2003.) |

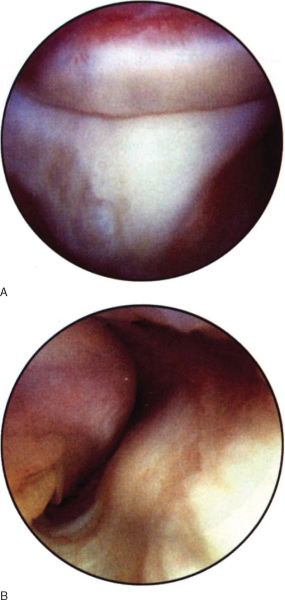

Through the direct lateral portal (

Fig. 31-10

), the articulation of the olecranon, radial head, and capitellum can be seen. Again, supination and pronation of the forearm allow viewing of 75% of the radial head articular surface. The capitellum can be seen and most of the smooth convex surface can be examined through this portal. The olecranon fossa can also be evaluated at this position. The scope can then be positioned posterior into the groove formed by the olecranon and trochlea. The entire olecranon can be seen from this vantage. The apophyseal scar can be viewed at the midpoint as a bare area of roughened articular cartilage. The undersurface of the trochlea should be visible when the scope is turned anteriorly. The posterolateral corner and capsule are viewed by looking posteriorly from the olecranon-trochlear groove. The posterior compartment can then be viewed for establishment of the posterior portals. If the 4-mm arthroscope is too large for this portal, a 2.7-mm arthroscope can be used.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-10 (From Phillips BB. Arthroscopy of upper extremity. In Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 2003.) |

The olecranon tip will be the first landmark seen through the posterolateral portal (

Fig. 31-11

). The triceps tendon insertion will be seen at the olecranon tip, where osteophyte formation may be noted posteromedially in patients with posterior impingement due to valgus extension overload. The olecranon fossa and posterior trochlear surface also can be seen from this position. Normally 50% to 60% of the ulnar collateral ligament can be seen when the scope is pushed medially and the posteromedial corner of the elbow is seen. The ulnar nerve is superficial to this area of the elbow and must be identified and protected.

|

|

|

|

Figure 31-11 (From Phillips BB. Arthroscopy of upper extremity. In Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 10th ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 2003.) |

The most common complication related to portal placement is nerve damage, which occurs in about 3% of procedures. Most of these injuries are to cutaneous nerves and are transient, although there have been isolated reports of major neurovascular injuries. These include irreparable damage to the ulnar nerve; transection of the ulnar, radial, and posterior interosseous nerves; and compression neuropathy of the radial nerve.

Drainage from a portal site occurs in approximately 2.5% of patients, but deep infection is less frequent (∼1%).

Andrews and Baumgarten, 1995.

Andrews JR, Baumgarten TE: Arthroscopic anatomy of the elbow.

Orthop Clin North Am 1995; 26:671-677.

Baker and Brooks, 1996.

Baker CL, Brooks AA: Arthroscopy of the elbow.

Clin Sports Med 1996; 15:261-281.

Baker and Jones, 1999.

Baker CL, Jones GL: Arthroscopy of the elbow.

Am J Sports Med 1999; 27:251-264.

Baker, 2003.

Baker Jr CL: Normal arthroscopic anatomy of the elbow: prone technique.

In: McGinty JB, Burkhart SS, Jackson RW, et al ed. Operative Arthroscopy,

3rd ed.. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Baker and Shalvoy, 1991.

Baker Jr CL, Shalvoy RM: The prone position for elbow arthroscopy.

Clin Sports Med 1991; 10:623-628.

Field et al., 1994.

Field LD, Altchek DW, Warren RF, et al: Arthroscopic anatomy of the lateral elbow: a comparison of three portals.

Arthroscopy 1994; 10:602-607.

Haapaniemi et al., 1999.

Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L: Case report. Complete transection of the medial and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of posttraumatic elbow contracture.

Arthroscopy 1999; 15:784-787.

Kelly et al., 2001.

Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW: Complications of elbow arthroscopy.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83:25-34.

Kim and Jeong, 2003.

Kim SJ, Jeong JH: Technical note. Transarticular approach for elbow arthroscopy.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:E27.

Kim and Jeong, 2003.

Kim SJ, Jeong JH: Transarticular approach for elbow arthroscopy.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:E37.

Meyers and Carson, 2003.

Meyers JF, Carson Jr WG: Elbow arthroscopy: supine technique.

In: McGinty JB, Burkhart SS, Jackson RW, et al ed. Operative Arthroscopy,

3rd ed.. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Micheli et al., 2001.

Micheli LJ, Luke AC, Mintzer CM, Waters PM: Elbow arthroscopy in the pediatric and adolescent population.

Arthroscopy 2001; 17:694-699.

Miller et al., 1995.

Miller CD, Jobe CM, Wright MH: Neuroanatomy in elbow arthroscopy.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4:168-174.

Morrey, 2000.

Morrey BF: Complications of elbow arthroscopy.

Instr Course Lect 2000; 49:255-258.

Papilion et al., 1988.

Papilion JD, Neff RS, Shall LM: Compression neuropathy of the radial nerve as a complication of elbow arthroscopy: a case report and review of the literature.

Arthroscopy 1988; 4:284-286.

Phillips and Strasburger, 1998.

Phillips BB, Strasburger S: Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:38-44.

Reddy et al., 2000.

Reddy AS, Kvitne RS, Yocum LA, et al: Arthroscopy of the elbow: a long-term clinical review.

Arthroscopy 2000; 16:588-594.

Savoie and Field, 2001.

Savoie III FH, Field LD: Arthrofibrosis and complications in arthroscopy of the elbow.

Clin Sports Med 2001; 20:123-129.

Selby et al., 2002.

Selby RM, O’Brien SJ, Kelly AM, Drakos M: The joint jack: report of a new technique essential for elbow arthroscopy.

Arthroscopy 2002; 18:440-445.

Soffer, 1997.

Soffer SR: Diagnostic arthroscopy of the elbow.

In: Andrews JR, Timmerman LA, ed. Diagnostic and Operative Arthroscopy,

Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997.

Steinmann et al., 2005.

Steinmann SP, King GJW, Savoie III FH: Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:2114-2121.

Stothers et al., 1995.

Stothers K, Day B, Regan WR: Arthroscopy of the elbow: anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:449-457.

Takahashi et al., 2000.

Takahashi T, Iai H, Hirose D, et al: Distraction in the lateral position in elbow arthroscopy.

Arthroscopy 2000; 16:221-225.

Thomas et al., 1987.

Thomas MA, Fast A, Shapiro D: Radial nerve damage as a complication of elbow arthroscopy.

Clin Orthop 1987; 215:130-131.