The Role of the Orthopaedic Surgeon in Diagnosing Child Abuse

part of human social interactions transcending time and cultures.

Recorded history indicates that violence toward children has been

condoned and even accepted. The nature of the abuse has encompassed a

broad spectrum of injuries inflicted on children and the neglect of

children by those who are responsible for their well-being. The notion

of children’s rights is relatively modern. Historically, paternal power

was absolute, including the right to abandon, abuse, and even kill

one’s child. Correction and discipline was limited only by the father’s

conscience. This right was extended to anyone involved in rearing the

child.

during the Industrial Revolution. Reaction to this practice was partly

responsible for the development during the 19th century of social

groups dedicated to the prevention of child abuse, and many societies

began to recognize child abuse as a problem that should not be ignored.

The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was established

in the mid-1800s. In 1860, Ambrose Tardieu reported 32 cases with the

physical signs that are typical of abuse, which included cutaneous

lesions, fractures (before x-ray films were available), subdural

hematomas described as “thickening of blood on the surface of the

brain,” and death. His report also addressed the social aspects of the

relationship between the abused and the abuser.

community’s attention on this problem with his publication in 1946

describing the association between long-bone fractures and subdural

hematomas. In 1962, approximately 100 years after Tardieu’s first

report, the term “battered child syndrome” was coined by C. Henry Kempe

(2). It reported one of the most dramatic

manifestations of family violence and implied that children are injured

by being struck by or thrown against something. When first described,

it was suggested that battered child syndrome “should be considered in

any child with a combination of multiple fractures, subdural hematoma,

failure to thrive, and soft-tissue swellings or skin bruising; when

sudden, unexplained death occurred; and in situations in which the type

and degree of injury were inconsistent with the history.”

an important figure in formulating the concept of “unrecognized trauma

in infants.” He advocated the term “syndrome of Ambroise Tardieu” in

recognition of the French physician’s pioneering work. The “Child Abuse

Prevention Act” in 1974 and the subsequent development of state

reporting laws in the United States followed the publication of Kempe’s

and Silverman’s articles (4).

The popular term “battered child” was recognized as inadequate at that

time, but it had an impact. Since then, the concept of child abuse has

been broadened to include the entire spectrum of childhood injuries

including physical and emotional neglect as well as physical,

psychological, and sexual abuse. “Manifestations of the Battered-Child

Syndrome,” by Akbarnia et al., (6) was one of the early reports on this topic in orthopaedic literature. It appeared in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery in 1974 and alerted orthopaedists to the existence and prevalence of this problem.

nonaccidental injury (NAI). Defining a condition by what it is not is

unsatisfactory. The adoption of this terminology not only requires an

acceptable definition of what constitutes an accident, but also

suggests that any injury that does not fit that definition is child

abuse. In addition, it diminishes the gravity of the active infliction

of harm by the abuser and thereby deflects attention from the

perpetrator.

intent to cause harm? Although the definition must include the fact

that the act was willful (otherwise, it would truly be accidental), the

assailant may not be aware of the consequences of his or her actions.

Therefore, premeditation is not required to diagnose abuse. The type of

handling and magnitude of the force involved is on the opposite end of

the spectrum of the reasonableness with which parents and caregivers

should gently, tenderly, and lovingly care for children. Some

understanding of behavior patterns that are typical of those

responsible for the care of a child must be considered when determining

if an act constitutes abuse. In addition, the definition must be

comprehensive to include the spectrum of childhood injuries. Defining

it with precision remains a challenge even for experts.

must be able to encompass the scope of the problems that must be

included in the spectrum of child abuse. We recognize today that child

abuse fits in the spectrum of family violence (7).

Most people now consider abuse ônot as a discrete illness entities or

syndromes, but as symptoms of different issues and risks for particular

children in individual families’ (8).

“Child abuse consists of any act of commission or omission that

endangers or impairs a child’s physical or emotional health and

development. Child abuse includes any damage done to a child which

cannot be reasonably explained and which is often represented by an

injury or series of injuries appearing to be nonaccidental in nature” (9). Included are forms of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse as well as neglect. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act

(CAPTA) defines child abuse and neglect as “at a minimum, any act or

failure to act resulting in imminent risk of serious harm, death,

serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, or exploitation of a

child by a parent or caretaker who is responsible for the child’s

welfare.”

orthopaedic aspects of this spectrum. Several good reviews of this

topic are available, and the reader is referred to them (10,11). The chapter on child abuse in the previous edition of this text is also excellent (4).

United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to

establish a national data collection and analysis program to make

available information on child abuse and neglect that is reported at

the state level. The department responded by establishing the National

Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). NCANDS is a federally

sponsored effort that collects and analyzes annual data on child abuse

and neglect submitted voluntarily by all the States and the District of

Columbia.

releases its most current child abuse statistics, as reported by the

states, in April of each year. The statistics reported in the following

text were released in April 2004 and represent an analysis of the data

for calendar year 2002 (US Department of Health and Human Services,

Administration for Children and Families. Child Maltreatment 2004:

Reports from the States to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data

System). This was accessed by the present author on November 21, 2004

at http://www.acf.dhhs.gov/programs/cb/stats/ncands/. The results are available in a publication called Child Maltreatment 2002 (12).

of abuse and neglect (an increase from 826,000 just 2 years earlier).

An estimated 2.6 million referrals of abuse or neglect concerning

approximately 4.5 million children were received by child protective

service agencies. More than two-thirds of those referrals were accepted

for investigation or assessment (most others were unsubstantiated).

annually, making child abuse more common than developmental dysplasia

of the hip and 30 times the incidence of new cases of myelomeningocele.

It is widely held that child abuse is significantly underreported (13).

The actual incidence of abuse and neglect is estimated to be three

times the number that is reported to authorities. All statistics should

be considered suspect, as they represent only the tip of the iceberg.

neglect were made by such professionals as educators, law enforcement

and legal personnel, social services personnel, medical personnel,

mental health personnel, child daycare providers, and foster care

providers. Educators made 16.1% of all reports, whereas law enforcement

made 15.7%, and social services personnel made 12.6%. Only 7.8% of

reports were made by medical personnel. Such nonprofessionals as

friends, neighbors, and relatives submitted approximately 43.6% of

reports.

African Americans had the highest rates of victimization. While the

rate of white victims of child abuse or neglect was 10.7 per 1000, the

rate among Native Americans or natives of Alaska was 21.7 per 1000

children, and for African Americans, it was 20.2 per 1000 children.

Half of all victims were white.

neglect (including medical neglect), approximately 20% were physically

abused, approximately 10% were sexually abused, and 6.5% were

emotionally or psychologically maltreated. In 2002, an estimated 1400

children died of abuse or neglect (more than three children per day)—a

rate of 1.98 per 100,000 children nationally. This is a significant

increase from an estimated 1300 children who died in 2001. Most (84.5%)

of the children who die are younger than 6 years. Forty-one percent of

the fatalities were in children under the age of 1 year. Three out of

four fatalities occur in children younger than 4 years. Abuse of girls

is slightly more common than abuse of boys (48% male; 51.5% female; the

victim’s sex was not reported in 0.5% of cases.) Most victims were

abused by a parent (81%), although reported sexual abuse by a parent

occurs in the minority. The median age of the perpetrators was 31 years

for women and 34 years for men.

Fractures are the second most common presentation in child abuse (skin

lesions are the most common). More detailed analysis of the nature and

frequency of abusive fractures will be provided in the subsequent

section on fractures.

maltreatment are available at the National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse

and Neglect Information at 1-800-394-3366, or http://nccanch.acf.hhs.gov/index.cfm.

promoted the thinking that child abuse is a culmination of a series of

stresses that impinge on parents and children. This idea is based on

Helfer and Kempe’s three elements that contribute to the propensity for

abuse: a child with qualities that are provocative; a parent with the

psychological predisposition; and a stressful event that triggers a

violent reaction (5). In Bittner and

Newberger’s model, there are social and cultural factors that provide a

background in which a family develops. Family stresses (caused by the

child, by the parent, and by social/situational factors) provide an

environment in which a triggering situation can lead to maltreatment of

the child. How the risk for child abuse may operate in any individual

family must be assessed clinically. They proposed that the team of

clinicians must understand the social, familial, psychological, and

physiologic concomitants of child abuse in order to assess the

situation and subsequently develop a comprehensive management plan.

regarded it as a constitutional predisposition to violence, the signs

of which appear only in the presence of an environmental stressor. This

is analogous to someone with a dust allergy who does not respond with

an allergic reaction unless placed in a dusty environment.

from different sources will likely lead to different risk profiles,

incidence, ratios of physical abuse to sexual abuse to neglect, and so

on.

|

TABLE 34.1 RISK FACTORS FOR CHILD ABUSE

|

|

|---|---|

|

NCANDS) and reviews of records from medical data gathered through

hospital systems will almost certainly differ. Interpreting these data

can be misleading and must be done with care. Underreporting in certain

segments of the population may also skew the results. Notable areas of

concern are risk profiles that identify minorities or ethnic groups and

those in the lower socioeconomic class as being more likely to abuse

their children.

for child abuse can help society to focus limited resources for its

prevention and detection on situations that present a high risk. One

might also believe that health care providers with a knowledge of risk

factors will pay closer attention to an injured child whose social

situation is characterized by numerous risk factors for child abuse.

However, because abuse can affect children in all environments,

dismissing the injuries of a white child from a more advantaged

background as not being caused by abuse, without adequate

investigation, is a disservice to that child. Health care providers

have a moral and legal obligation to maintain a high index of suspicion

to avoid underdiagnosis of vulnerable individuals.

plausible history. This fact emphasizes why orthopaedic expertise

regarding fracture mechanisms is required. Understanding the

antecedents of the child’s injury and assessing the plausibility of the

history are two of the initial goals of history taking. For example,

the body mass of a child younger than 12 months typically will not

generate sufficient force to fracture a normal bone in a fall from a

bed, crib, or couch. One must suspect abuse when a nonambulatory child

presents with a fracture. Of course, an insufficiency fracture through

pathologic bone is another possibility in the differential. Because

injuries of any kind are rare in nonabused infants, age is one of the

most important factors in making the diagnosis of child abuse.

impossible, and even with older children it is typically brief and

consists of asking the child how the injury occurred and, in the case

of apparent abuse, who inflicted the injury. The interviewer should

assess the child’s affect and developmental status, and observe the

child’s verbal and behavioral interactions with family members and

other adults. Interviews of caretakers should be more detailed and must

be done separately. Thorough medical and developmental histories must

be obtained.

than healthy developing children. Indications of abuse are the same in

both groups. Behavioral indicators in a child with a disability may not

be recognized or may be attributed to the underlying condition. Risk

factors include increased demands for care, chronic stress on the care

providers, parental attachment problems, parental isolation,

unrealistic expectations, aggressive behavior in the child,

communication limitations leading to decreased ability to report

information about the abuse, inability to communicate specific needs

resulting in neglect, and increased dependency on many caretakers (17).

Children with severe disabilities may be at increased risk of

malnutrition and failure to thrive. Malnutrition is sometimes accepted

as part of the disability, but it can be viewed as neglect to provide a

basic bodily need (18,19).

Some children’s developmental disorders are due to abuse, for example,

shaken baby syndrome can lead to cerebral palsy. There is a lack of

adequate studies regarding the incidence and nature of abuse in

children with disabilities, but these children certainly represent a

vulnerable population. Awareness of the uncommon Munchausen syndrome by

proxy (20) will help avoid missing this complicated form of abuse.

response to potential maltreatment. Cooperation and liaison with

official community agencies such as the child protection service (CPS),

law enforcement, and prosecutors is crucial and legally mandated. Open,

good-faith exchange with these agencies is legal and protected. It is

not restricted by the Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability

Accountability Act (HIPAA).

document a description of the injury. Whether that is the orthopaedist

or another member of the health care team depends on the local medical

community and the situation of the particular case. Use quotations when

possible, identify “players,” control information exchange, do not

suggest a mechanism of injury, and avoid confrontation, accusation, and

prejudicial statements. Document everything including parental behavior

and the presence of visitors. The interviewer should keep in mind that

questioning does not equal blaming. Immediately address the concern

that the injuries may have been inflicted. What has happened cannot be

changed, what is happening currently can be stopped, and abuse that

could occur in the future can be prevented. The needs of the child and

provision of medical care to the child are the primary concerns and

should be given priority over the child abuse workup. Family-centered

care may have to take a back seat. The parents’ right to know needs to

be balanced against possible threats (direct or indirect) to the

child’s safety. Obtaining and documenting adequate information to rule

out inflicted injury is crucial, but these efforts are often

inadequate. Oral et al. (21) retrospectively

reviewed emergency room charts and orthopaedic office notes. In a large

percentage of cases, they found that documentation was insufficient to

explain the cause of fractures and thereby rule out inflicted trauma.

They advocated the use of forms, protocols, and periodic chart review

to help ensure

compliance (see the section of this chapter entitled “Author’s Preferred Treatment”).

required. Again, the environment will determine which professional is

primarily responsible for this. If the child is seen in the emergency

room of an urban children’s hospital, an emergency room physician or

pediatrician will be accountable. If it is a more rural or isolated

environment, the orthopaedist may need to take a more active role. In

addition, the orthopaedist’s role will vary depending on whether the

cause of the injuries has already been identified as abuse at the time

of consultation. If so, the role will be to ensure that all

musculoskeletal injuries are found and to document their nature and

severity. If abuse is not known or suspected, then only professional

awareness and a high degree of suspicion will identify the cause of the

injury.

that soft-tissue injuries were present in 92% of children suspected of

being victims of child abuse (14). A child’s

age, the pattern and location of soft-tissue injury(s), the number of

injuries, and the age of the lesion(s) are all important to consider.

The classic soft-tissue lesions such as cigarette burns, bite marks, or

multiple linear ecchymoses in the shape of an electrical cord leave

little doubt that abuse occurred, but in McMahon’s report these were

uncommon. Therefore, these findings are quite specific, but not

sensitive. The examiner must be careful to identify subtle signs of

abuse, because the “classic” findings may be present in only some

abused children, typically in the more severe cases.

pain on movement of the injured extremity, swelling at the fracture

site, and deformity. Dos Santos et al. (22)

found that less swelling was present on presentation in children with

long bone fractures caused by abuse than similar fractures that

occurred because of accidents. The history and the reported time when

the injury occurred are often unreliable in cases of child abuse.

Frequently, delays in seeking care for these children allow resolution

of these acute signs and symptoms. The absence of the typical acute

findings of fractures in abused children is one of the reasons that

screening for fractures in suspected cases of abuse includes skeletal

surveys and bone scans (see the section in this chapter entitled “Other Imaging Studies”).

is suspicious and indicates possible abuse. Soft-tissue injuries of the

head and face are much more common in abused children and are rare in

the absence of abuse. Ecchymoses are common, but may not be of the

suspicious pattern (14). Soft-tissue injuries are less common after accidental injury, but do occur frequently in approximately 37% of cases (23).

Therefore, the mere presence of a soft-tissue injury does not clearly

imply that the injury was a result of abusive force. Location is

important, because toddlers commonly have bruises over the shins,

knees, elbows, and brow. They may have a few old cuts or scars around

the eyes or cheekbones because of normal collisions. However, bruising

of the buttocks, perineum, trunk, back of the legs, and especially the

head or neck suggests inflicted trauma.

signs of multiple fractures in various stages of healing, the same is

true for skin lesions. Wilson (24) has

suggested the following guidelines for estimating the age of a bruise

from its color: from 0 to 3 days after injury, a bruise usually is red,

blue, or purple; from 3 to 7 days, it is green or green-yellow; and

from 8 to 28 days, it is yellow or yellow-brown.

These lesions can be scalding injuries, cigarette burns, or burns

caused by flames. Burns are most common among children between birth

and 2 years of age (14). The pattern of

deliberate immersion burns often is symmetric, with sharp lines between

the burned and unburned skin. Accidental scald burns usually are

distributed asymmetrically (25).

be invaluable in cases of child abuse. It is best to obtain more than

one view, with different lighting. Many centers have protocols in place

for obtaining satisfactory and complete photographs.

classic article in 1946 reported the association between long-bone

fractures and subdural hematomas. Typically, one of two histories is

provided: (i) a fall from a short height or a similar minor, blunt

traumatic episode is described, or (ii) the baby is brought for medical

attention due to the development of symptoms including poor feeding,

irritability, vomiting, seizures, lethargy, breathing difficulties, and

unresponsiveness (26). The head is the most

vulnerable part of the body for accidental injury and child abuse

because of its relatively large size, the weak neck muscles, and the

less dense bone with open sutures in younger children. The type of

skull fracture is not specific for identifying cases of child abuse, as

similar fractures may occur in different settings (27).

due to child abuse. Essentially, all the injuries that are known to be

caused by blunt trauma can be seen in victims of child abuse. Death due

to child abuse can be caused by internal hemorrhage because of the

rupture of abdominal organs after punches or kicks. The death rate from

these injuries can be high and is attributable to both the severity of

the trauma and the delay in diagnosis. Delays can result from lack of

timely diagnosis in the emergency room or delays on the part of the

abuser in seeking medical attention for the child. Hematuria can be one

sign of blunt internal injury. It is often the recognition of other

signs of abuse, however, along with a high index of suspicion for

associated abdominal trauma, that is required to identify this

potentially life-threatening type of injury.

conjunctival hemorrhage and orbital swelling. Retinal hemorrhages in

infancy are almost invariably caused by shaking and are seen in shaken

baby syndrome (28).

ortho-paedists if all abusive fractures had a typical appearance.

Although there are some patterns of fractures that are distinctive,

many of the patterns are also seen in cases of accidental trauma (Table 34.2). There is some debate as to which patterns are most common. Loder and Bookout (29)

noted that suspicious fracture patterns include metaphyseal corner

fractures, lower extremity fractures in nonambulatory children,

bilateral acute fractures, rib fractures, spine fractures, and physeal

fractures in young children. Kleinman (13)

stated that the most likely fracture in an abused infant is a long bone

metaphyseal lesion, followed by rib, skull, and long bone shaft

fractures. Kleinman et al. subsequently reported on the challenges of

dating the characteristic metaphyseal fracture (30). Blakemore et al. (31)

reported that single, fresh, long bone diaphyseal fractures are most

common. It is likely that there is a sampling bias that explains some

of these discrepancies, but different standards for radiographic

technique and the frequency with which skeletal surveys, follow-up

skeletal surveys, and bone scans are done may also lead to variations

in the reported rates (13).

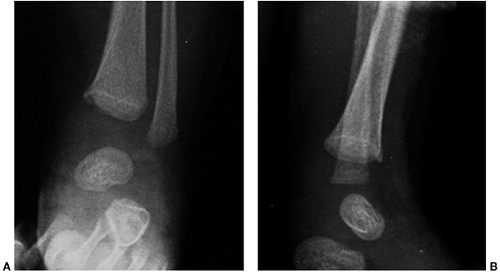

being inflicted by abusive trauma. Metaphyseal “bucket-handle” or

“corner” fractures often form the basis for the diagnosis of abuse (Fig. 34.1) and are considered pathognomonic for abusive trauma. They have highly distinctive radiographic characteristics (32)

that result from the isolation of a mineralized disc (or a part

thereof) that can be seen radiographically. Depending on its size and

the orientation and angle of the radiograph, one will see a

bucket-handle lesion, corner fracture, or metaphyseal lucency. The

metaphyseal lesion may be difficult to identify on plain radiographs.

High-detail imaging may be needed. Kleinman (13) prefers the term classic metaphyseal lesion (CML) to describe this type of injury because it represents a radiologic alteration that most

closely satisfies the need for an objective finding that “regardless of

history in an otherwise normal patient, can be viewed as a highly

specific inflicted injury.” He states that it is rarely seen as an

isolated finding in a healthy infant for whom a plausible accidental

event is available to explain the injury, and it is invariably due to

severe indirect forces. Most injuries due to child abuse “occur by

indirect forces which develop as the child is grabbed by an extremity,

shaken, slammed, or hurled into a solid object” (13).

They occur because of avulsive forces applied to the periosteal

attachment to the surface of the metaphysis. The periosteum serves as

the anchor for the epiphyseal cartilage to the metaphysis. Failure of

the bone in this area results in a corner fracture. The bucket-handle

fracture results from the same type of indirect force, but represents a

separation of a crescentic fragment from the zone of provisional

calcification that is tipped into an oblique plane (33).

|

TABLE 34.2 SPECIFICITY OF RADIOLOGIC FINDINGS

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Figure 34.1 Classic metaphyseal lesion of the distal tibia in a 2-week-old infant. A: Anteroposterior ankle. (B:) Lateral ankle. This finding is pathognomonic for child abuse.

|

be difficult to diagnose due to the various sutures, synchondroses, and

fissures that may be present throughout the development of a child.

Diagnosing these variants as a fracture is a common pitfall. Fractures

appear as radiolucent, sharply etched lines that may or may not branch

but finally taper and become indistinct. Sutures, on the other hand,

have a serpiginous appearance, symmetry, sclerotic edges, and typical

anatomic positions (34). Vascular markings are

more linear, have a near constant anatomic branching pattern, and

involve only the inner table. Other radiographic views or computed

tomography (CT) scan of the head can assist in cases that are

confusing. As mentioned previously, the type of skull fracture is not

specific for identifying child abuse. Similar fractures can occur in

different settings (27).

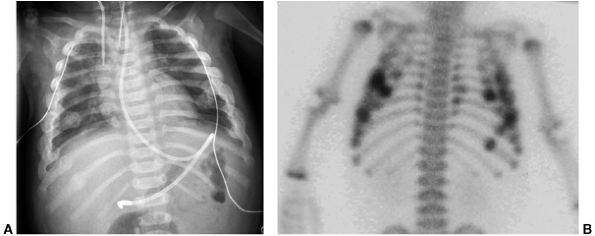

multiple rib fractures in children younger than 2 years) are highly

suggestive of intentional injury (Figs. 34.2 and 34.3).

The amount of force required to inflict them makes these injuries very

unlikely to be accidental. Rib fractures (especially posterior) may be

difficult to detect, but are not uncommon in children who are abused.

In a study of 62 children younger than 3 years with rib fractures (316

collectively), the finding of a rib fracture had a positive predictive

value of 95% for the diagnosis of abuse. The positive predictive value

rose to 100% after the exclusion of children with a defined history of

accident or disease (35).

|

|

Figure 34.2

Acute skull fracture in a 5-month-old abused child. This fracture could be consistent with accidental injury if there were a documented history of significant trauma (a fall or auto accident). |

|

|

Figure 34.3 Multiple healing rib fractures seen on chest x-ray film (CXR) (A) and on bone scan (B) in the same child as in Figure 34.2. The findings of multiple healing rib fractures (including posterior) and the acute skull fracture (Fig. 34.2) clearly indicate child abuse.

|

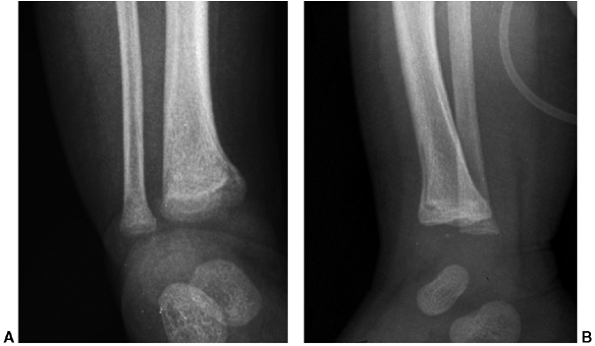

radiologist arises when the radiographic appearance of a fracture

resulting from abuse is not characteristic. Many of the fracture

patterns caused by abuse can also be seen after accidental trauma (Fig. 34.4).

In this situation, making the correct diagnosis is more difficult. In

such cases, age is one of the most important factors in differentiating

accidental from abusive trauma (31,36).

Some fractures that would not raise suspicion in ambulatory children

(because they are common and accidental) do not occur in infants unless

excessive force is applied and therefore are highly suspicious for

abuse in this age-group. For example, a spiral fracture of

the humerus in a young child is particularly indicative for abuse. Strait et al. (37)

reported that abuse was rare (1 of 99 cases) in children older than 15

months presenting with humeral fractures, but these fractures in 9 of

25 children younger than 15 months were diagnosed as having been caused

by abuse.

|

|

Figure 34.4 Metaphyseal fracture of distal femur in a 13-month-old child. A: Anteroposterior view. B:

Lateral view. Was this fracture caused by abuse, or was it accidental? This fracture pattern could be seen in either situation. If the child were 4 months old, the fracture would be very suspicious for abuse. At 13 months of age, and if the child is ambulatory, it could be accidental. |

tibia or femur are common accidental injuries in toddlers, but are

suspicious if the child is preambulatory (31).

There is no diaphyseal fracture pattern that is specific for abuse.

Twisting injury to an extremity causes spiral fractures. In the

ambulatory child, the twists associated with falls while walking,

running, climbing, or falling down stairs are sufficient to cause

fractures (38). It is impossible for a

preambulatory child, however, to sustain this level of trauma unless it

is applied to him/her directly. Transverse or oblique long bone

fractures, on the other hand, are more common with abusive injury than

are spiral fractures. The peak incidence of pediatric femur fractures

is between 2 and 3 years of age (39). Femur fractures can result from low-energy falls and are two to three times more common in boys than in girls (40). King et al. (41)

found that approximately half of the 189 abused children in their

retrospective study had a single fracture and that a transverse

fracture was the most common type (as was the case for the child

illustrated in Fig. 34.4).

vast majority (13 of 14) of nonaccidental femur fractures occurred in

children younger than 1 year. Comparing them with 33 femoral fractures

known to be caused by accident, the authors concluded that there is no

specific radiographic site or fracture pattern that allows

differentiation between accidental and nonaccidental femoral fractures.

Blakemore et al. (31) also felt that age is the

most important factor in diagnosing abuse, because isolated femur

fractures are commonly seen in children who are 1 to 5 years of age.

Some authors would suggest that the incidence of long-bone fractures

caused by abuse in ambulatory children is relatively low (31,36). Dalton et al. (43)

recommended that because 31% of 138 femoral fractures in children

younger than 3 years were due to abuse, and only 10% (one third of the

total abuse cases) were identified as abuse at admission, a high index

of suspicion must be maintained even in the ambulatory child. They

recommended that although the “cause of isolated shaft fractures in

young children is low, the clinician should still have a high degree of

vigilance and have the circumstance investigated when the history and

physical findings are disturbing.” Only 18% of 34 humerus shaft

fractures in children younger than 3 years were classified as probably

caused by abuse in the review by Shaw et al. (44).

The history and physical findings (not the fracture pattern itself)

were critical in establishing cause. Neither age nor fracture pattern

is pathognomonic of abuse, so suspicion should remain high.

had skeletal surveys. In addition, for any fracture to be categorized

as abuse, its cause had to be confirmed at a legal hearing. Therefore,

interpretation of the scope of the results of this study seems to be

limited, because inclusion in the category of abuse was quite

restricted (some abused children may have been placed in the accidental

injury group) and screening for fractures was not highly sensitive

(some fractures may have been missed). Maintaining a high degree of

suspicion may even uncover abuse when an isolated long bone fracture in

an infant caused by a legitimate injury mechanism is investigated

further (45). In the review by Strait et al. (37), 18.5% of 124 humerus fractures were indeterminate in children younger than 15 months.

that isolated fractures of the femur are analogous to the toddler’s

fracture of the tibia. Like other authors, they concluded that the

ability to walk was the strongest predictor of abuse. Ten (42%) of 24

children

not old enough to walk had been abused, whereas only 3 of 115 toddlers

had been. Although child protective services were frequently consulted,

the authors felt that it may have been unnecessary in 42% to 63% of

cases. They felt that unless other evidence of abuse such as an

inconsistent history, bruises, or other fractures was present, abuse

was very unlikely in the child old enough to walk.

but occur in the minority of abused children. Only 17% of the 904

abused children in the report of Merten et al. (46) had fractures. McMahon et al. (14)

in their review of 371 abused children found that most did not show the

classic signs of child abuse that we, as orthopaedists, expect to see.

Although only 9% had fractures identifiable on x-ray film, 92% had

soft-tissue injuries (ecchymosis was most common). The metaphyseal

lesion was not seen, and long bone fractures tended to be diaphyseal.

Although the McMahon article is very enlightening regarding abused

children who do not present with the classic findings, only 10% of the

children included in the report actually had radiographs taken! One can

only speculate as to the number and type of fractures that may have

been found if full skeletal surveys had been performed. The rate of

fractures reported by different authors depends on the source of the

information (social service agencies vs. orthopaedists offices vs.

emergency rooms, etc.) and the methods employed to identify fractures.

Because neglect is the most common form of abuse, and neglected

children do not commonly have fractures, it is likely that few victims

of abuse have fractures. However, orthopaedists are typically not

involved in many cases of neglect; therefore, from our vantage point,

it can be presumed that a substantial percentage of the young patients

we see with fractures have been abused. Approximately 30% of fractures

in children younger than 3 years (27) and 56% of fractures in children younger than 1 year have been found to be nonaccidental (16).

Although corner fractures, fractures at different stages of healing,

and injuries at multiple sites may be more specific, the clinician must

remember that all types of fractures at all locations can be seen in

children who have been abused (Table 34.2).

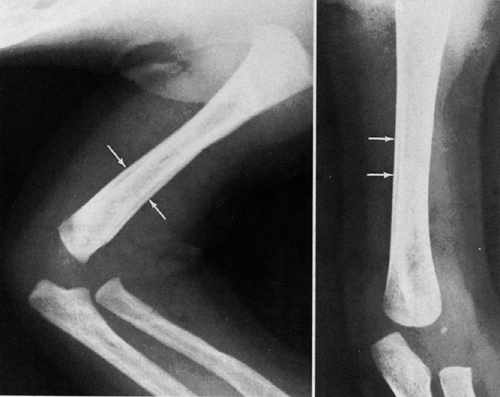

stages of healing can be important in identifying abuse, it is

extremely important to be able to identify the ages of fractures based

on their radiographic appearance (47,48) (Table 34.3).

Soft-tissue swelling may be the only radiographic finding for recent

fractures. The orthopaedist is accustomed to identifying this finding

on x-ray films of acute fractures. Because care for abused children is

frequently delayed, this finding may be absent on the initial

radiographs. The earliest sign of bone healing is subperiosteal new

bone formation (SPNBF). SPNBF will not be seen until at least 5 days

after injury. This finding has low specificity as there are multiple

etiologies (see “Differential Diagnosis”

section), and it must be distinguished from the many other conditions

that can lead to this radiographic appearance. Indistinctness of the

fracture line is the next finding that helps to date the fracture

between approximately 10 days to 2 weeks (Fig. 34.5). Soft callous formation and

indistinctness of the fracture line date fractures to similar

ages—between 2 and 3 weeks. Numerous factors (age of the child,

mechanism of injury, fracture stability, and fracture location)

determine whether either or both are seen. The subsequent stages of

hard callous formation and remodeling are even more variable, but are

typically distinct from the early findings. It would likely be

impossible to distinguish a fracture that is 4 weeks old from one that

is 6 weeks old. Subsequent growth that separates a physeal fracture

from the physis (Salter-Harris growth arrest line) helps identify older

fractures (Fig. 34.6).

One should remember that not all fractures heal at the same rate. For

example, an ulnar diaphyseal fracture will heal more slowly than a

coexisting distal radial metaphyseal fracture (a common combination

seen when both bones of the forearm fracture). During healing they can

have the radiographic appearance of fractures of different ages. One

should be aware of such possibilities.

|

TABLE 34.3 TIMETABLE OF RADIOLOGIC CHANGES IN CHILDREN’S FRACTURESa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Figure 34.5

Subperiosteal new bone formation (SPNBF). Lateral x-ray film of the humerus showing a healing fracture and typical SPNBF in an 11-week-old infant. Although this fracture pattern itself is not very troubling, the finding of a long bone fracture in an infant is very suspicious for abusive trauma. |

|

|

Figure 34.6 Healing classic metaphyseal lesion (CML). A: Antero-posterior view. B: Lateral view. This is the same patient who also had the humeral shaft fracture shown in Figure 34.5. This fracture pattern along with the findings in Figure 34.5 clearly indicates that these fractures were caused by abuse.

|

scans is that many fractures from abuse are not apparent on physical

examination. Accurate diagnosis of abusive injury can be reached in

most cases by careful appraisal of the social and family history,

combined with painstaking clinical radiographic and other imaging

evaluations.

It is necessary for two primary reasons. As mentioned, the typical

physical findings of fractures (pain with movement of the injured

extremity, swelling at the fracture site, and deformity) may be absent

in abused children (22). In addition,

identifying multiple fractures can be crucial to the diagnosis of child

abuse. The additional information may prove invaluable during a

subsequent investigation and prosecution. American Academy of

Pediatrics guidelines state that a skeletal survey should be mandatory

in all cases of suspected physical abuse in children younger than 2

years (49). In children older than 5 years,

skeletal survey and bone scan have little value as screening tools.

Injuries in children in the 2 to 5 year age-group should be handled

individually (Table 34.4).

vary from one source to another, but the American College of Radiology

has published standards for skeletal survey imaging in cases of

suspected abuse (50) (Table 34.5).

Additional views may be included in some hospitals. For example at one

of the local hospitals in the author’s community, lateral views of both

arms and lower extremities, five views of the skull (anteroposterior,

both laterals, Towne, Waters), and cone down views of tibia and fibula,

with internal rotation if the child is ambulatory, are included in the

routine skeletal survey to assess child abuse. “Babygrams” do not

provide sufficient radiographic detail. They are inadequate for

screening for abuse and should not be accepted.

Quality

and adequacy of the skeletal survey images must be assured by a

radiologist. With the trend to convert to digital radiographic

techniques, digital image quality must be comparable to high-detail

film screen radiography before it replaces the standard techniques.

|

TABLE 34.5 STANDARD SKELETAL SURVEY

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

skeletal survey versus bone scan in screening for child abuse. Bone

scans are particularly sensitive for detecting rib fractures, subtle

shaft fractures, and early periosteal elevation (51).

Bone scans can help identify unsuspected sites of skeletal injury or

occult or subtle lesions seen on plain radiographs. The bone scan can

be negative acutely. There is also concern that the bone scan may miss

subtle spine fractures and CMLs due to the typical increased level of

activity seen at the growth plate on bone scans. Both fulfill the need

for screening children who are too young to localize pain for the

examiner. Bone scans lack specificity, are more expensive, and expose

the child to a radionuclide. Any lesions identified on the bone scan

must be followed up with radiographs. Conventional radiographs have the

advantages that they are easy to perform, can be interpreted in

minutes, can differentiate from other pathologies such as tumor and

infection, can show different stages of healing, and are less

expensive. Both modalities are felt to be sensitive. The specificity is

high for skeletal survey and low for bone scintigraphy.

found that radiographs were positive in 105 cases and false-negative in

32. Bone scans were positive in 120 and false-negative in 2. The

authors concluded that scintigraphy should be the screening procedure

of choice in cases of suspected abuse. Mandelstam et al. (53)

found that 20% of children with inflicted injuries were identified on

bone scan only. Like other authors, they also found that the CML can be

missed on bone scan (only 35% were identified). The authors concluded

that neither a bone scan nor a skeletal survey is ideal, but they

provide complementary information to one another. Therefore, they

recommended that both studies be done in suspected cases of physical

abuse. Flynn et al. (40) suggest a bone scan

when abuse is suspected and the skeletal survey is negative or

equivocal. Follow-up skeletal survey 2 weeks later has been shown to

increase the diagnostic yield and should be considered when abuse is

strongly suspected, but not confirmed initially (54).

The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Radiology states that if

the child is in a safe environment, a follow-up skeletal survey in 2

weeks could be considered instead of initial bone scan. Bone scan does

not obviate the need for a second skeletal survey (49).

adequate with plain radiographs, particularly in cases of nonossified

epiphyses. The proximal femur and the elbow are common examples. Repeat

close-up views in proper alignment that are centered over the physis in

question may be sufficient when coupled with a good knowledge of normal

anatomy and consideration of comparison views to the contralateral

side. If not, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or

arthrography can be considered for further imaging of these challenging

anatomical areas.

and children with suspected intracranial injury. These studies are not

considered standard components of the evaluation in all suspected abuse

cases. They should be considered for a child younger than 1 year who

presents with a history of serious trauma, brutality, or shaking, or a

child who presents with serious bruising or trauma, abdominal trauma,

or a positive skeletal survey (34). CT scan of

the head may not clearly document subdural bleeding, but it does

provide diagnostic and clinical information needed for immediate

management of the child. CT scan is better than MRI for evaluation of

acute hemorrhage and can detect cranial and facial fractures. Delayed

MRI (5 to 7 days) is recommended because acute hemorrhage may not be

detected initially. It offers very high sensitivity and specificity in

subacute and chronic situations. In a few days, hemorrhagic areas

become bright on T2-weighted images as fresh blood turns to

methemoglobin.

spinal injury resulting in paralysis will have negative radiographs

[spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA)]. MRI of

the spine is the imaging modality of choice. Thoracoabdominal trauma

can be evaluated with a CT scan if the child is stable. Evaluation and

management are similar to those in cases of accidental trauma.

presents with any signs of bruising, so coagulation studies must be

obtained.

ophthalmology consultation must be obtained. Shaking is a key element

in creating hemorrhagic retinopathy (28).

Certain patterns of hemorrhagic retinopathy are particularly indicative

of shaking, with a very narrow differential diagnosis.

osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), and several less common skeletal diseases

must be considered in the differential diagnosis of fractures caused by

abuse. The skeletal diseases in the differential for child abuse are

listed in Table 34.6. They receive little or

no mention in this text as they are listed in the table, and more

information is available in the excellent work by Brill et al. (55).

The more common challenge that the orthopaedist will face is

distinguishing abusive injuries from accidental and obstetric trauma,

normal variants, and OI.

that extends from the cortical surface to the endosteal margin. They

result from vessels that course through dense cortical bone. Normal

metaphyseal variants, including beaking, step-offs, and spurs, must be

distinguished from the CML (56). The absence of

a fracture line or its presence bilaterally can help differentiate

these from abuse. The typical finding of metaphyseal beaking of the

proximal tibia in toddlers (Fig. 34.7) could be mistaken for the CML of child abuse, especially during healing (Fig. 34.6B).

Physio-logic SPNBF is a recognized normal variant in the long bones of

infants between 1 and 6 months of age and most commonly involves the

femur, humerus, and tibia (Fig. 34.8). It is not uncommon and has been reported to be present 30% to 50% of the time (57).

It is radiographically indistinguishable from other conditions that

cause SPNBF, such as diaphyseal fractures, osteomyelitis, and

congenital syphilis.

radiographic appearance of long-bone fracture patterns, it should be

clear that differentiating accidental from abusive trauma represents

the most common challenge for the orthopaedist. Falling down the stairs

or from a height can result in fracture patterns that are similar to

fractures caused by abuse. Parents and caretakers may not be

aware

of the risks associated with a child’s attainment of new developmental

milestones (climbing up on objects, climbing down stairs, falling

down). As mentioned earlier, age and attainment of toddlerhood is a

primary consideration when trying to determine whether a fracture was

accidental or not (31,36,37,38,40,42,43,44). The amount of soft-tissue swelling may be a helpful sign. Dos Santos et al. (22)

found that less swelling was present initially in long bone fractures

caused by abuse than similar fractures that were accidental. The

authors concluded that the history and the time of the injury may not

be reliable in suspected cases of abuse.

|

TABLE 34.6 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SKELETAL DISEASES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Figure 34.7 Normal metaphyseal beaking of the proximal tibia in a toddler. (From Keats TE, Atlas of normal roentgen variants that may simulate disease 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1996:564.)

|

and multiple rib fractures. Even this constellation of findings is not

specific for abuse, as injuries due to motor vehicle accidents can

result in the same findings (27).

classic differential diagnostic challenges that the orthopaedist and

radiologist can face. Claiming that their child has OI can be a common

defense used by an abusive family in legal defenses. The classification

of Sillence (58,59) is

well known. For the purposes of this discussion, only a brief summary

will be offered. The reader is referred for further details of this

condition to Chapter 8. OI is a rare disorder

of type I collagen (incidence of approximately 1 in 25,000 live

births). OI type I is mild and is typically distinguished by distinctly

blue sclerae (however, some children with OI type I do not have blue

sclerae). OI type II is lethal in the perinatal period. OI type III is

severe and causes progressive deformity. OI type IV is typically a

milder form, with normal sclerae. Of the two subtypes, type IVA has no

dentinogenesis imperfecta. OI is either dominantly inherited or occurs

sporadically as a consequence of a new mutation. However, mosaicism has

been reported and could explain the occurrence of more than one

affected child to apparently “unaffected” parents. The only types that

represent a practical differential challenge of abuse are the unusual

type I OI without blue sclerae and type IVA OI.

|

|

Figure 34.8 Normal subperiosteal new bone formation (SPNBF) in an infant with no history of trauma or fracture. (From Keats TE, Atlas of normal roentgen variants that may simulate disease 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1996:422.)

|

instrumental in confirming cases of OI when abuse is otherwise

considered to be the cause (60). If testing is

indicated, a skin biopsy for cultured dermal fibroblasts can detect

approximately 85% of OI cases. Collagen analysis to exclude type IV OI

is recommended only in rare cases in

which the diagnosis of child abuse remains in doubt after thorough

evaluation by clinicians in consultation with experienced radiologists (61). When faced with making this distinction, clinicians can rely on several helpful points (40).

Child abuse is much more common than OI (3 in 100 vs. 1 in 25,000).

Typically, a family history is present in OI. Common abusive injuries

(skull and rib fractures, subdural hematomas, retinal hemorrhages, and

metaphyseal corner fractures) are not associated with OI. Although

normal infants younger than 4 months may have blue sclerae, they do not

have the dental findings, osteopenia, or wormian bones on skull

radiographs seen in children with OI. If there is a reliable reporter

and a history of multiple fractures with minimal trauma, OI is likely.

Smith offered these guidelines (62):

-

In suspicious circumstances, suspect child abuse.

-

Consider collagen testing if

-

bruises or burns are not seen

-

the reported injury seems too minor to have caused a fracture

-

fractures occur in different environments

-

placed in protective custody. In such an environment, a child with OI

type IVA will still fracture. The fractures will likely cease to occur

in the abused child. Children with OI can also be victims of abuse (63).

Collagen synthesis testing is rarely required to rule out OI, as the

diagnosis would have already been strongly suspected in most cases (64).

measurements to differentiate between abuse and OI is unknown, as

values for BMD are not available for either typically developing

children younger than 2 years or for children with OI.

techniques. Clavicular fractures are most common and occur not only

with difficult deliveries but also with uneventful deliveries of large

babies. They can be associated with brachial plexus palsies. Some are

only noted incidentally on subsequent x-ray films, so they may be more

common than reported in the literature. Humerus fractures occur with

breech deliveries and have become much less common with the increased

utilization of cesarean section. Sonography can help with

identification of proximal humeral physeal fractures. Absence of SPNBF

at 11 days of age is compelling evidence against a birth injury (65).

Subdural hematoma can be caused by obstetric trauma. Evaluation of

obstetric injuries has provided useful insight into the biomechanics

and imaging characteristics of inflicted skeletal injuries.

following their review of 39 children younger than 1 year with

fractures. They felt that these infants had a “self-limiting variant of

OI” due to a transient defect in collagen formation. Since its

introduction in 1990, this condition has stirred intense controversy. A

number of medical authors and legal proceedings have challenged the

findings of this paper. It has been pointed out that none of the

authors was a radiologist, thereby bringing into question the accuracy

of their findings. Most of the radiographic features of this condition

are the same as those seen in child abuse (68). Paterson et al. (66,67)

reported that some fractures developed after hospitalization. Although

they concluded that this was consistent with the transient osteopenic

state, it is well documented that some abusive fractures occurring

before hospitalization become evident only on follow-up studies. Ablin

and Sane (61) stated that “until clinical

research scientifically establishes the existence of temporary brittle

bone disease, it should remain strictly a hypothetical entity and not

an acceptable medical diagnosis,” and Albin states, it “remains a

medical hypothesis lacking the support of sound scientific data” (69).

Legal proceedings involving testimony by Paterson have cast doubts on

his findings. The possibility of temporary brittle bone disease may

“compromise or obstruct protection of a child” and that by being aware

of and referring others to relevant law reports, pediatricians can help

keep the issues in perspective (70).

indicated that there were approximately 20 cases reported in the world

literature, and fractures as late sequelae of copper deficiency have

never been reported. British courts have sought to define what is

acceptable opinion versus untried hypothesis. “Untested and

unacceptable views should not be put forward—advice American courts

should take note of in this age of ôpseudoscience’ in the courtroom” (70).

injury caused by abuse is the same as traumatic fractures and

soft-tissue injuries due to other causes. The pathoanatomy of the CML

is pathognomonic for abuse. It has been described in detail by Kleinman

et al. (32) in a classic article that received

the Society for Pediatric Radiology John Caffey Award. The authors

studied four children who died because of their injuries. The

histopathology of their lesions was correlated with fracture patterns

on pre- and postmortem radiographs and anatomy from autopsy specimens.

The CML is due to a series of subepiphyseal planar fractures through

the most immature part of the metaphyseal bone. The separation occurs

in the region of transition from the zone of calcified cartilage to the

primary spongiosa. If the injury extends to the periphery of the bone,

it undermines and isolates a peripheral fragment of bone encompassing

the periosteal collar. The periosteum serves as the anchor for the

epiphyseal cartilage to the metaphysis. The CML occurs because of

avulsive

forces

applied to the periosteal attachment to the surface of the metaphysis.

The result is the isolation of a mineralized disc (or a part thereof)

that can be seen radiographically.

documents thickening of the zone of hypertrophic cartilage, with some

cases showing extension of the growth plate into the metaphysis.

Because estimating the age of CMLs is difficult, the authors suggested

that the extent of healing may be helpful in dating these fractures.

abuse and death. It is accepted and well known that a high percentage

of children will be reinjured and some will die if they are returned to

the abusive environment. Therefore, abuse must be diagnosed, and either

some intervention or removal of the child from the abusive environment

must be enforced.

trickiest aspects of managing this condition. Kleinman writes that, as

with other clinical situations, “the most effective approach to

diagnosis is one based on thoughtful and measured acquisition of data

that is carefully analyzed in the light of one’s knowledge and

experience” (13). Managing fractures due to

abuse is typically not difficult or challenging. Identifying all

fractures, making the diagnosis, and instituting the process to protect

the child from reinjury are the challenging aspects of child abuse.

easy. To feel angry is human. As professionals, controlling our

emotional response is essential in carrying out our responsibility to

care for and protect the child. Particularly in cases that are less

clear, the physician should try to form a relationship with the family

which will foster their participation in the subsequent diagnostic and

therapeutic workup. One must also explain the case report and aspects

of the protective service process to the family.

advise that all children younger than 1 year with a fracture be

admitted to the hospital and referred to a pediatrician for child

protection assessment. Management should be multidisciplinary, with the

key being recognition because of the risk to the abused child (11).

Such teams and resources are available in most, if not all,

institutions. The importance of diagnosing abuse and intervening on

behalf of the vulnerable child cannot be overemphasized.

the potential disincentives for a practitioner to initiate an

investigation or to make the diagnosis. Advance preparation and

knowledge about the process may help minimize this potential

disincentive. Physicians have certain rights that they should expect to

be able to exercise when they testify (72).

-

The right not to know

-

The right to understand the question

-

The right to ask for a question to be repeated

-

The right not to be confused

-

The right to refresh one’s memory

-

The right to ask if a factual statement or an opinion is being requested.

-

Factual information about the child’s fractures

-

Possible mechanism of injury

-

Amount of force/energy needed to cause the fractures

-

Dating fractures

-

Judge information based on reasonable medical certainty

-

Potential for future fractures

chapter on child abuse in the previous edition of this book has an

extensive section on medicolegal issues for the orthopaedist. It is

excellent and recommended for the reader interested in more

information. Further insights to diffuse these concerns are addressed

in the following text.

many fractures. We should ask ourselves if we recognize abusive

fractures when we see them. The reported maltreatment rate is 1% to

1.5% annually. Given the widely held belief that child abuse is

significantly underreported, this incidence is likely to be lower than

the actual rate of occurrence. Fractures are the second most common

presentation in child abuse. These statistics should cause us to pause

and wonder whether we recognize the etiology of abusive fractures often

enough. Some are obvious; diagnosing the rest is where the challenge

lies.

is essential for the orthopaedist to consider two key issues. The first

is that we must have a high index of suspicion.

Without it, we will not recognize abuse often enough. Many of us also

care for children with disabilities, and must remember that they are

particularly vulnerable. Not only are they at increased risk of

physical injury; medical neglect in the form of lack of provision of

adequate nutrition by the caregiver is not uncommon. We should

recognize this when it is present, and ask our pediatrician colleagues

to assess and intervene.

insidiously erode our willingness to report suspicious fractures and

institute the process. The clinician may also feel psychosocial

pressure to not report cases that are of concern. We may want to avoid

putting a family through the embarrassment of filing a report and

completing an investigation. Methods to minimize these disincentives

are addressed later in this section.

becoming overzealous. One must remember that ambulatory status is a

very strong predictor of likely abuse. Child Protective Services may be

consulted unnecessarily in some cases (36).

Unless other evidence of abuse such as an inconsistent story, bruises,

or other fractures is present, abuse of the toddler (who might, for

example, have a toddler’s fracture of the tibia) is much less likely

than abuse of the infant. Of course, there are enthusiasts on both

sides. Physicians and other professionals practicing in this field may

seek to simplify matters, taking extreme positions that reflect either

an overly passionate approach to diagnosing abuse or an unwillingness

to consider abuse in all but the most flagrant cases. Financial rewards

for legal counsel may increase the zealousness with which cases are

pursued.

effective and safe care. The following resources are those that I have

found to be particularly useful. Paul Kleinman’s multiauthored book Diagnostic Imaging of Child Abuse 2nd ed. (13)

is an essential reference for all centers. Dr. Kleinman is a

radiologist with a worldwide reputation for his expertise in the field

of child abuse. During his career, he has been active in research and

education.

auspices of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America Trauma

Committee (Chairman: Peter Pizzutillo, M.D.) in 2002 (40).

It is a very useful, quick-glance guide that is also handy for

residents’ education. It is available by emailing John M. Flynn, M.D.

at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia-Flynnj@email.CHOP.edu.

contains reviews of recent peer-reviewed articles on the diagnosis,

prevention, and treatment of child abuse and neglect. Medical, legal,

mental health, and social work professionals known for their expertise

and experience summarize the articles which are chosen from more than

1000 medical journals. The reviewers offer opinions about the validity

and significance of the research findings.

|

TABLE 34.7 AVOIDING PITFALLS

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

“child protective services is unlikely to do anything” is a self-fulfilling prophecy and should not happen (72).

Consulting the physicians and staff of referral centers that specialize

in the management of child maltreatment removes at least some of the

disincentive to reporting. Many physicians are uncomfortable in the

courtroom. Much of the legal work can be handled by expert physicians

who work in referral centers. In this case, the orthopaedist may not be

needed as often in court. If disincentives are removed, we can be

appropriately suspicious. The radiologist and members of the referral

center staff can be more objective and more detached from psychological

pressures to not report. These centers are typically referred to as

children’s advocacy centers [the local center in my community is the

Midwest Children’s Resource Center (MCRC) in St. Paul, Minnesota,

United States]. They typically utilize the multidisciplinary team (MDT)

approach for the treatment or prevention of child abuse and neglect in

their respective communities. Many provide 24-hour coordination of

suspected child abuse and neglect (SCAN) cases, integrating hospital

services with outside community agencies. They can formulate and

provide many of the necessary protocols mentioned in the preceding

text. They partner pediatric subspecialty consultants (hospital MDTs)

with providers in the community (community MDTs). A hospital MDT

includes physicians, nurses, social workers, and risk managers. A

community MDT includes law enforcement, child protection investigators,

and county attorneys. Child abuse consultants provide expertise in

diagnosis of inflicted trauma. The medical care team is therefore more

free to first and foremost provide medical care.

consultation for case reviews, telephone consultation, and expert

testimony. They are also active in education for both health care and

community providers, often supporting combined, multidisciplinary

interaction and education. They typically offer both medical and

psychological assessments. The National Association of Children’s

Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI) is considering designating

qualifying programs as centers of excellence. They provide training

supported by a national grant from the Department of Justice. The

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Child Abuse and Neglect

(SOCAN) maintains a listing of these centers across the United States

and Canada. This can be accessed at http://www.aap.org/sections/scan/ and the link “State Child Abuse Programs.” Numerous policy statements are available on this website as well.

enforcement to the teams at referral centers. Those in law enforcement

add expertise in acquisition of information and the ability to evaluate

and photograph the scene of the injury. They can provide an evaluation

and report on conditions in the home, the number of calls for domestic

disputes that have been made, and whether there is any prior history of

intervention. The initial report to the appropriate police department

is oral and is followed by a written report.

was organized to support individuals and organizations working to

protect children from abuse and neglect worldwide. Founded in 1977, it

is the only multidisciplinary international organization that brings

together a worldwide cross section of committed professionals to work

toward the prevention and treatment of child abuse, neglect, and

exploitation globally. ISPCAN’s mission is “to prevent cruelty to

children in every nation, in every form: physical abuse, sexual abuse,

neglect, street children, child fatalities, child prostitution,

children of war, emotional abuse, and child labor. ISPCAN is committed

to increasing public awareness of all forms of violence against

children, developing activities to prevent such violence, and promoting

the rights of children in all regions of the world.” The organization’s

journal, Child Abuse and Neglect: The International Journal is published by Elsevier Science (http://www.elsevier.com).

ISPCAN partners with numerous national organizations such as American

Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC) in the United

States.

consultation only, or one may consider referring a child to a tertiary

referral center for assessment and management. These referrals may be

helpful because such centers have the equipment and expertise to

perform the necessary studies and interpret them appropriately.

Although it is impractical to restrict evaluations to specialized

centers, the scope of services they offer may be helpful to the

orthopaedist. Alternatively, developing connections to access the

consultative services of a pediatric radiologist with expertise in the

field could be valuable to the orthopaedist without ready access to a

specialized center in his or her local area.

Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and

Committee on Children with Disabilities. Assessment of maltreatment of

children with disabilities. Pediatrics 2001; 108(2):508–512.

R, Blum KL, Johnson C. Fractures in young children: are physicians in

the emergency department and orthopedic clinics adequately screening

for possible abuse? Pediatr Emerg Care 2003;19(3):148–153.

DM, Barbor P, Hull D. Unusual injury? Recent injury in normal children

and children with suspected non-accidental injury. Br Med J 1982;285:1399–1401.

AC, Partington MD. Overview and clinical presentation of inflicted head

injury in infants. In: Adelson PD, Partington MD, guest eds. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 2002;13(2):149–154.

PK, Marks SC, Spevak MR, et al. Extension of growth-plate cartilage

into the metaphysis: a sign of healing fracture in abused infants. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;156:775–779.

LC, Loder RT, Hensinger RN. Role of intentional abuse in children 1 to

5 years old with isolated femoral shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16(5):585–588.

KA, Char E, Bensard DD, et al. The positive predictive value of rib

fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma 2003;54:1107–1110.

RT, Siegel RM, Shapiro RA. Humeral fractures without obvious etiologies

in children less than 3 years of age. When is it abuse? Pediatrics 1995;96:667–671.

SA, Rosenfield NS, Leventhal JM, et al. Long-bone fractures in young

children: distinguishing accidental injuries from child abuse. Pediatrics 1991;88(3):471–476.

the POSNA Trauma Committee, 2002 Chairman: Peter Pizzutillo, MD, John

M. Flynn, MD at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Flynnj@email.CHOP.edu.

SA, Cook D, Fitzgerald M, et al. Complementary use of radiological

skeletal survey and bone scintigraphy in detection of bony injuries in

suspected child abuse. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:387–389.

RD, Pepin M, Byers PH. Studies of collagen synthesis and structure in

the differentiation of child abuse from osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr 1996;128:542–547.

CR, Burns J, McAllion SJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta: The distinction from

child abuse and the recognition of a variant form. Am J Med Genet 1993;45:187–192.

PA, Scotland TR, Myerscough EJ. Fractures in children younger than age

1 year: importance of collaboration with child protection services. J Pediatr Orthop 2002;22(6):740–744.