Tennis Elbow Release

isolated to the lateral aspect of the elbow. The condition arises from

tendon degeneration at the origin of the wrist extensor tendons, most

commonly the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), from the lateral

humeral epicondyle. The tendon degeneration is due to repetitive wrist

extension against resistance and is commonly seen in recreational

tennis and racquetball players. The microscopic pathology noted in the

degenerated tendon is termed angiofibroblastic hyperplasia, which

demonstrates chronic tendinosis rather than acute inflammation.

|

|

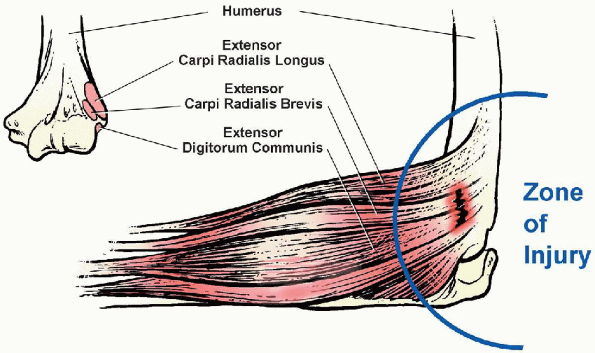

FIGURE 8-1.

The forearm extensor muscles originate as a conjoined tendon from the lateral epicondyle of the elbow. Note critical zone of injury. |

lateral humeral epicondyle, and pain is exacerbated by resisted wrist

extension. Nonoperative treatment consisting of cryotherapy, activity

modification, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication, rehabilitation,

and cortisone injections generally relieves the symptoms in 85% to 90%

of patients. A supervised physical therapy program focusing on

flexibility, strengthening, and endurance of the wrist extensor

mechanism is continued for at least 6 months before surgical

consideration. Severe, persistent pain that fails to respond to

conservative treatment is the main indication for surgery.

|

|

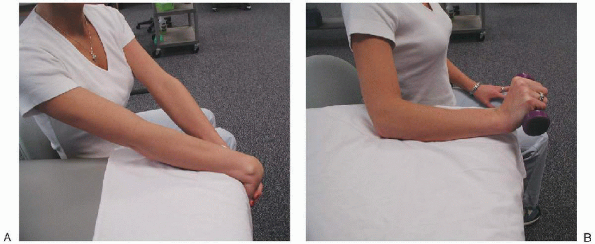

FIGURE 8-2. Physical examination reveals pain with the provocative maneuver of resisted wrist extension with the elbow in full extension.

|

extensor carpi radialis longus, ECRB, extensor digitorum communis,

extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris. The extensor

muscles originate as a conjoined tendon from the lateral epicondyle of

the elbow. Lateral epicondylitis is most commonly localized to the ECRB

tendon, and the involved area is located approximately 2 cm distal and

anterior to the center of the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 8-1).

It is less commonly seen in the anteromedial edge of the extensor

communis or the undersurface of the extensor carpi radialis longus and

is rarely present in the extensor carpi ulnaris.

tenderness over the origin of the conjoined tendon from the lateral

epicondyle of the elbow. This condition characteristically occurs in

the dominant extremity of the middle-aged athlete (e.g., tennis player)

and is caused by the repetitive, eccentric contractile activity of the

extensor muscles of the forearm. This overuse activity leads to ECRB

degeneration and angiofibroblastic hyperplasia as described by Nirschl.

Angiofibroblastic hyperplasia refers to the microscopic invasion of

fibroblasts and vascular granulation-like tissue that occurs in the

degenerative tendon. Three pathologic categories of lateral

epicondylitis have been described by Nirschl: category I, acute,

reversible inflammation without angiofibroblastic invasion; category

II, partial angiofibroblastic invasion; category III, extensive

angiofibroblastic invasion with or without partial or complete rupture

of the tendon. The degree of angiofibroblastic hyperplasia correlates

with the severity of symptoms.

|

|

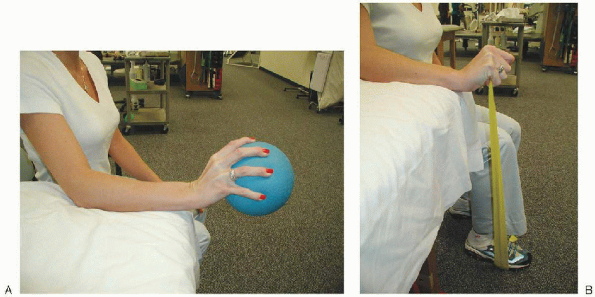

FIGURE 8-3. Rehabilitative program consists of wrist extensor stretching (A) and progressive strengthening (B) exercises.

|

localized pain, which may radiate into the forearm. Physical

examination reveals tenderness just distal and anterior to the lateral

epicondyle, corresponding to the location of the ECRB. The provocative

maneuver of resisted wrist extension with the elbow in full extension

reproduces the pain (Fig. 8-2). Passive range of motion is typically preserved, and the involved extremity’s neurovascular status is unaffected.

calcifications or a lateral epicondyle exostosis in up to 25% of

patients. Magnetic resonance imaging may show increased signal in the

musculotendinous structures at the lateral elbow but is seldom needed

to make the diagnosis.

interosseus nerve (PIN) or radial tunnel syndrome and radiocapitellar

articular disease. PIN syndrome is caused by entrapment of the

posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve at the arcade of

Frohse. This condition is characterized by diffuse anterolateral elbow

pain. Typically, pain is exacerbated by resisted forearm supination,

and maximal tenderness to palpation

is

approximately 5 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle over the proximal

radial forearm musculature. Patients with radiocapitellar articular

disease often present with clicking and pain with elbow motion.

Radiographs reveal degenerative changes at the radiocapitellar

articulation. A thorough history and physical examination is the key to diagnosing lateral epicondylitis.

treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Nonsurgical treatment consists of

three phases: (a) pain relief, (b) rehabilitation, and (c) return to

sports and work. The initial phase of pain relief consists of activity

modification, and the use of ice, other local modalities, and

antiinflammatory medication. Corticosteroid injections deep to the ECRB

may be helpful during this phase by reducing pain and inflammation. Incorrectly

placed injections into the superficial tissues (resulting in

subcutaneous atrophy) or into the tendon (resulting in irreversible

structural changes) must be avoided. After the initial

discomfort of lateral epicondylitis has been relieved, a rehabilitation

program consisting of wrist extensor stretching and progressive

strengthening exercises may be started (Fig. 8-3).

Concentric and eccentric resistive exercises are added as flexibility

and strength improve. When exercises can be performed to fatigue

without pain, the patient begins progressive exposure to sport or

work-specific activities. A structured conditioning program for the

elbow focusing on flexibility, strength, and endurance training

eventually allows the patient’s return to full activity in most cases.

patients. Up to 25% of patients may have a recurrence of symptoms that

may respond to a similar nonsurgical therapeutic regimen. The primary

indication for surgical treatment is persistent, severe pain at the

epicondylar region that has failed a 3- to 6-month nonsurgical program.

-

No. 10 and no. 15 scalpel blades

-

Self-retaining retractor

-

Rongeur

-

7/64-inch drill bit and power drill

-

No. 1 absorbable suture

under the involved elbow. After administration of regional or general

anesthesia, a tourniquet should be applied before standard prepping and

draping. The elbow should be flexed to approximately 90 degrees with a

rolled towel under the distal humerus.

|

|

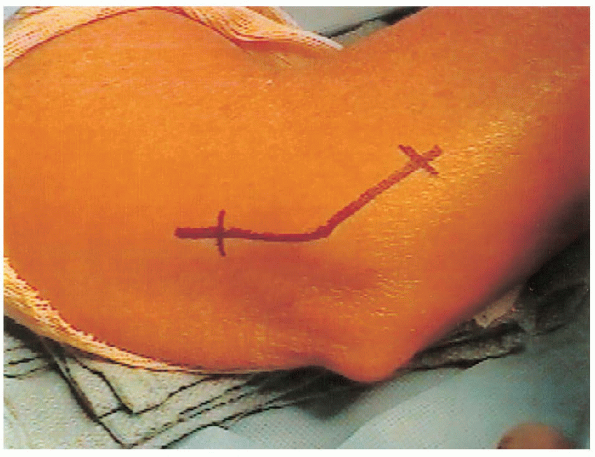

FIGURE 8-4. The curvilinear incision is longitudinally centered over the lateral epicondyle of the elbow.

|

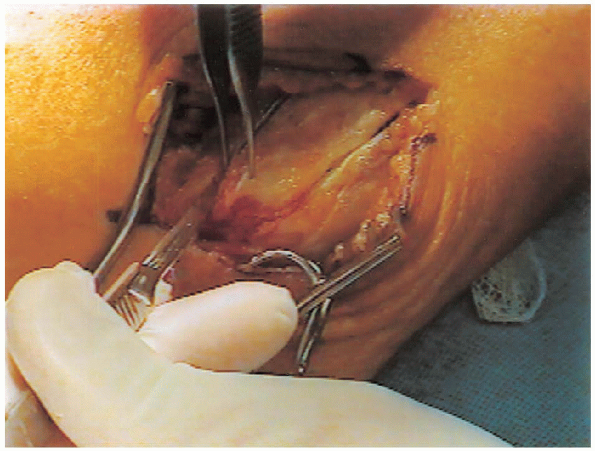

surgical landmarks consist of the prominent lateral epicondyle and the

lateral supracondylar ridge of the distal humerus. Palpating the

forearm extensor mechanism attachment aids the identification the

lateral epicondyle. A curvilinear incision centered over the lateral

epicondyle is made (Fig. 8-4). The proximal

limb of the incision should be centered over the supracondylar ridge of

the distal humerus. Anterior and posterior subcutaneous flaps are

raised to identify the origin of the conjoined tendon at the lateral

epicondyle (Fig. 8-5).

|

|

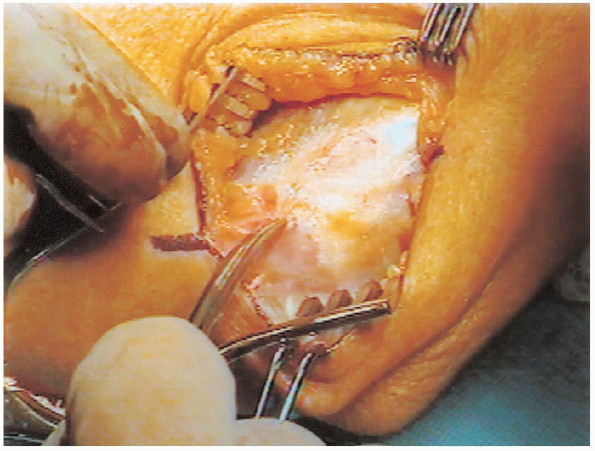

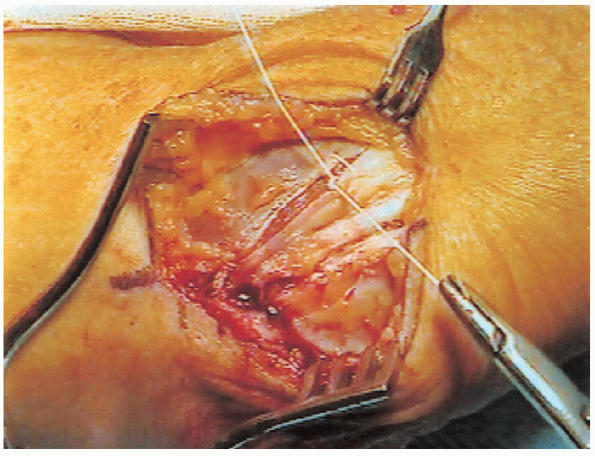

FIGURE 8-5.

Thick subcutaneous flaps are developed anteriorly and posteriorly to allow identification of the origin of the conjoined tendon at the lateral epicondyle. |

|

|

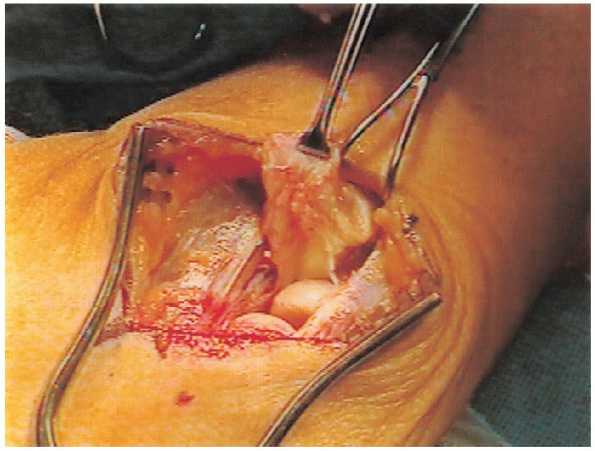

FIGURE 8-6. The anterior and posterior edges of the conjoined tendon are released from the lateral epicondyle.

|

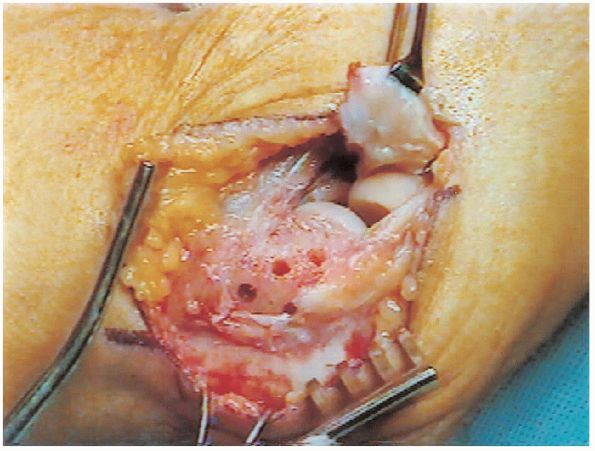

the origin of the conjoined tendon has been completely exposed, deep

dissection begins by releasing the anterior and posterior edges of the

conjoined tendon (Fig. 8-6). The extensor

origin is then sharply elevated off the lateral epicondyle with the

beveled edge of the no. 10 scalpel blade. Approximately a 2-cm wide

area of tendon is elevated with the underlying capsule and taken

distally (Fig. 8-7). Careful

attention should be paid not to extend the release to the posterior

aspect of the lateral epicondyle so as to avoid injury to the lateral

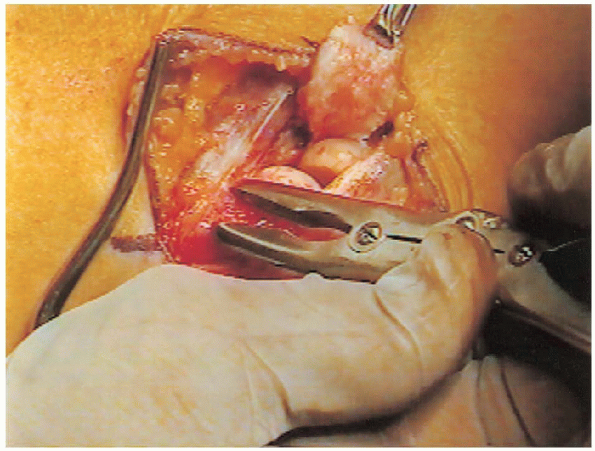

ulnar collateral ligament. The joint is inspected for articular

damage or loose bodies and irrigated. The entire lateral epicondyle can

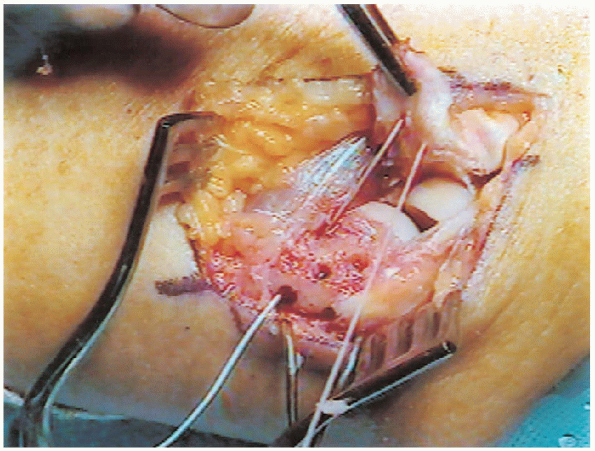

be visualized at this point. The rongeur is used to débride and gently

decorticate the lateral epicondyle removing any prominent ridges of

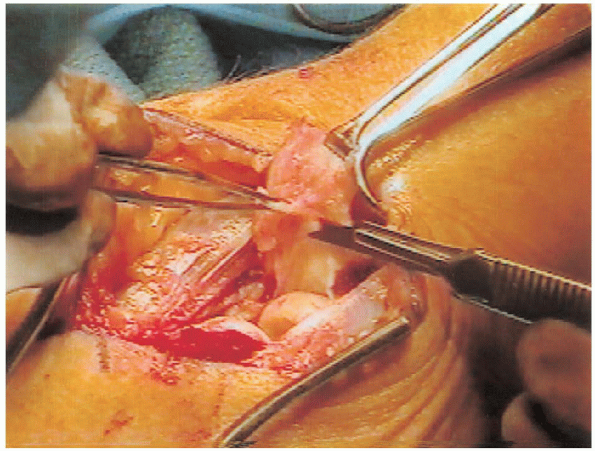

bone (Fig. 8-8). A scalpel blade is used to sharply débride the undersurface of the tendon aponeurosis (Fig. 8-9). The pathologic tissue is degenerative grayish-colored scar tissue (Fig. 8-10).

If corticosteroid injections were given before surgery, the white

granular residue may be noted during the débridement of the

undersurface of the tendon. Both edges of elevated tendon should be

débrided back to fresh healthy-appearing tissue.

|

|

FIGURE 8-7.

The conjoined tendon is elevated and taken distally with the elbow capsule. Note the degenerative scar tissue in the center of the undersurface of the tendon. |

|

|

FIGURE 8-8. A rongeur is used to débride and decorticate the lateral epicondyle.

|

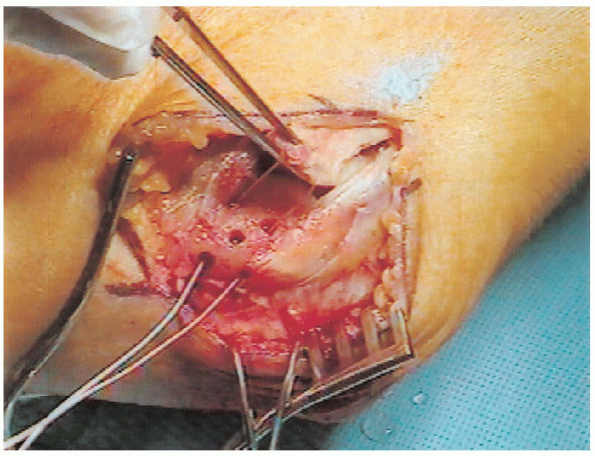

drill bit. Care is taken to preserve a 1-cm bone bridge between the

tunnels. An additional central hole is made to enhance healing of the

tendon to the epicondyle (Fig. 8-11). A heavy

no. 1 absorbable suture is passed distally through the anterior tunnel

and then through the tendon in a horizontal mattress fashion (Fig. 8-12).

The suture is then passed proximally through the posterior tunnel and

tied over the 1-cm bone bridge on the posterior aspect of the distal

humerus (Fig. 8-13). The tendon edges are then reapproximated

using a corner stitch. This is followed by reapproximation of the anterior and posterior margins of the tendon (Fig. 8-14) to complete the repair (Fig. 8-15).

|

|

FIGURE 8-9. The degenerative scar tissue is sharply débrided off the undersurface of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon.

|

|

|

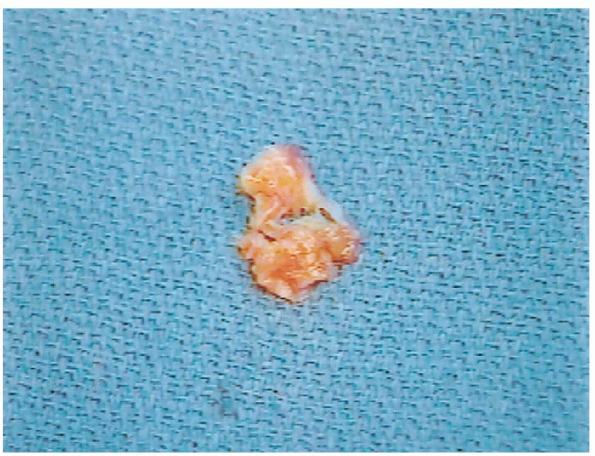

FIGURE 8-10. The pathologic tissue is a degenerative grayish-colored scar tissue.

|

arm splint is placed with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion, the

forearm in neutral rotation, and the wrist free.

surgery and passive range of motion exercises of the elbow, wrist, and

hand are begun. Isometric exercises are begun at 3 to 4 weeks

postoperatively (Fig. 8-16), and resistive wrist exercises are initiated at 6 weeks (Fig. 8-17). A progressive strengthening program ensues with return to full activity usually by 3 to 4 months (Fig. 8-3).

|

|

FIGURE 8-11.

The lateral epicondyle is prepared by drilling two transosseus tunnels with a 1-cm bone bridge between them posteriorly. A central hole is drilled to aid tendon healing to the decorticated bone. |

|

|

FIGURE 8-12. A suture is placed through the anterior bone tunnel and attached to the tendon in a horizontal mattress fashion.

|

|

|

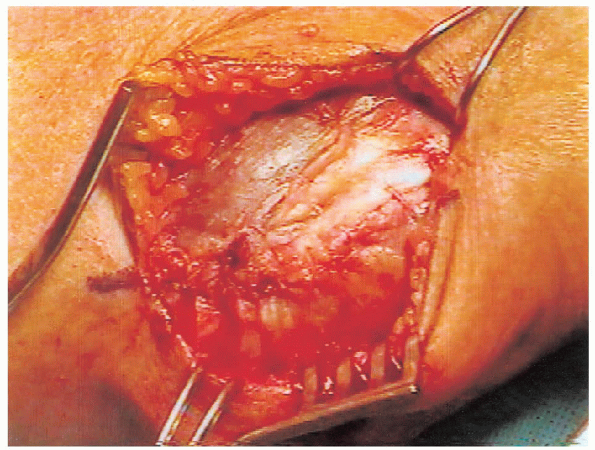

FIGURE 8-13.

The extensor tendon is reattached to the decorticated lateral epicondyle by a heavy absorbable suture that is weaved through two transosseous tunnels and secured posteriorly over a 1-cm bone bridge. |

|

|

FIGURE 8-14. Closure of the anterior margin of the tendon is accomplished using a simple suture and burying the knots deep to the tendon.

|

|

|

FIGURE 8-15. Final appearance of the lateral epicondyle region after the tendon repair has been completed.

|

|

|

FIGURE 8-16. Postoperative rehabilitation begins with isometric exercises at 3 to 4 weeks.

|

|

|

FIGURE 8-17. Postoperative rehabilitation continues with progressive resistive strengthening (A and B) starting at 6 weeks.

|