SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE LOWER EXTREMITY

– SURGICAL PRINCIPLES AND TECHNIQUES > CHAPTER 3 – SURGICAL

APPROACHES TO THE LOWER EXTREMITY

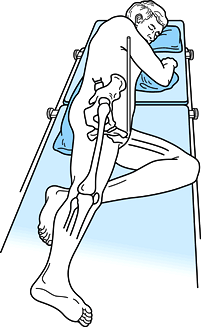

Hardinge described its use with the patient supine; however, most

surgeons today use the lateral/decubitus position because it provides

better access for two surgeons standing on opposite sides of the table.

It also allows for increased mobility of the operated extremity (Fig. 3.1).The

advantage of the supine position is that it makes orientation of the

components easier and facilitates comparison of leg lengths for

correction of discrepancy.

|

|

Figure 3.1. With the patient in the lateral decubitus position, notice that anterior superior iliac spines are vertically aligned.

|

femoral neck fracture, as well as for total hip arthroplasty. It allows

the surgeon direct visualization of the acetabulum and excellent access

to the entire circumference. It avoids morbidity from osteotomy of the

greater trochanter and maintains the continuity of the abductor

mechanism. Because the posterior portion of the gluteus medius muscle,

with its thick tendon, is left intact, early rehabilitation is

possible. Partial weight bearing with crutches is usually possible

immediately after surgery.

-

Begin the skin incision about 3–4 inches

(7 to 10 cm) distal to the prominence of the greater trochanter in the

midportion of the lateral aspect of the thigh, directly over the femur.

Extend it in line with the femur over the prominence of the trochanter,

inclining about 20° posteriorly in the proximal one-third of the wound.

The total incision length is usually 8–10 inches (20 to 25 cm); in

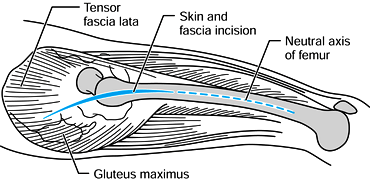

obese or muscular patients, a longer incision is necessary (Fig. 3.2).![]() Figure 3.2. Make the initial incision in line with the neutral axis of the femur.

Figure 3.2. Make the initial incision in line with the neutral axis of the femur. -

Incise sharply down to the deep fascia

with minimal undermining of the subcutaneous tissue. Divide the gluteal

fascia and iliotibial band in line with the skin incision. Retract the

tensor fascia lata anteriorly, separating it from its conjoined origin

with the gluteus medius. Avoid injury to the superior gluteal nerve and

artery by dissecting this interval with a relatively blunt instrument.

We prefer a large-key periosteal elevator (Fig. 3.3). Figure 3.3. Charnley initial incision retractor in place.

Figure 3.3. Charnley initial incision retractor in place. -

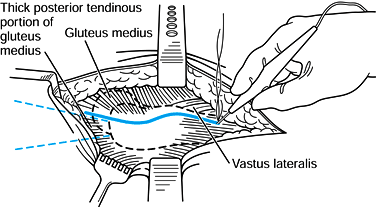

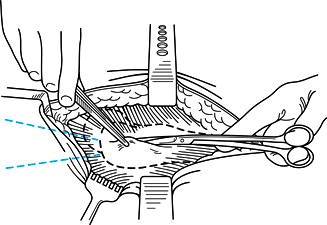

At the trochanteric ridge formed by the

origin of the vastus lateralis, at the mid-lateral point of the greater

trochanter, use an electrocautery knife set on “cutting” to incise the

gluteus medius longitudinally, extending distalward through the vastus

lateralis, curving slightly

P.31

anteriorly.

Control bleeding from the transverse branch of the lateral circumflex

artery in the vastus lateralis origin. Reflect the gluteus medius

insertion and vastus lateralis muscles in continuity anteriorly off the

greater trochanter, taking care to stay on bone to maintain the maximum

thickness of tendon. Do not cut across the muscle fibers of the gluteus

medius proximally; split them in line with the incision with a

large-key periosteal elevator. Do not split proximally more than 5 cm

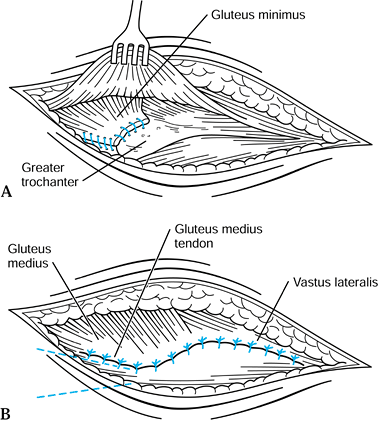

above the trochanter to avoid injury to the superior gluteal nerve (Fig. 3.4).![]() Figure 3.4. Anterior insertion of the gluteus medius is mobilized.

Figure 3.4. Anterior insertion of the gluteus medius is mobilized. -

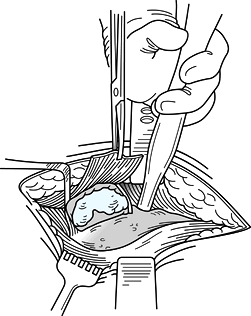

Retract the gluteus medius; in the supine

position, adduct the thigh to facilitate exposure of the gluteus

minimus, which is reflected off the hip joint capsule superiorly. In

his original description, Hardinge incises the capsule, does not excise

it, and repairs it following arthroplasty. To permit adequate access to

the acetabulum for noncemented cups, we prefer to isolate the hip joint

capsule, placing a cobra retractor anteroinferiorly and

superoposteriorly to expose the capsule. We then excise the anterior

two thirds of the capsule intact (Fig. 3.5). Figure 3.5. Expose the capsule.

Figure 3.5. Expose the capsule. -

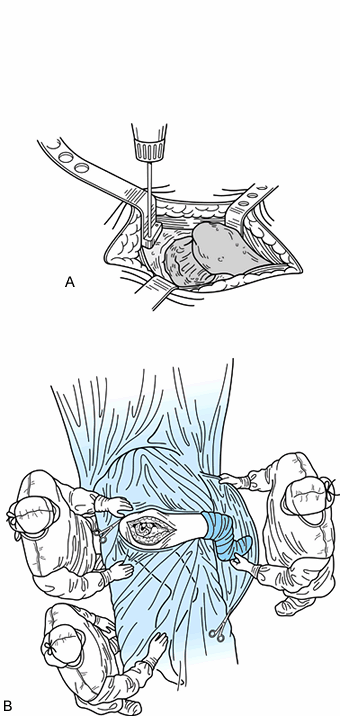

Dislocate the hip by flexing and

adducting it while levering the femoral head out of the acetabulum,

cutting the ligamentum teres. When using the lateral decubitus

position, drop the leg off the edge of the table into a sterile pocket

formed from a large drape sheet. Transect the femoral neck with an

oscillating saw (Fig. 3.6A).![]() Figure 3.6. A: Superior retractor is held in place by 1/8 in. Steinmann pins or drill bits. B: Place the tibia in a pouch positioned vertical to the floor.

Figure 3.6. A: Superior retractor is held in place by 1/8 in. Steinmann pins or drill bits. B: Place the tibia in a pouch positioned vertical to the floor. -

This position gives ideal exposure of the

femur for insertion of a prosthesis. Protect the insertion of the

posterior portion of the gluteus medius during preparation of the femur

with appropriate retractors, which also elevate the trochanter to

provide better exposure (Fig. 3.6B). -

When preparing and inserting the

acetabulum, keep the leg on the operating table in line with the torso,

using specially designed or sharp-tipped Hohmann retractors to

facilitate exposure of the acetabulum. -

For repair of the gluteus medius, place a

series of heavy (we prefer #5 Tevdek) sutures through the bone of the

greater trochanter. Then direct the suture in a horizontal mattress

fashion through the tendinous portion of the gluteus medius, securing

it firmly to bone. Make these holes and place the sutures prior to

insertion of the prosthesis using an awl, drill-point, or towel-clip.

Next, repair the longitudinal split in the gluteus medius and vastus

lateralis with #1 sutures. Close the split in the deep fascia and

iliotibial band in a similar fashion (Fig. 3.7). Figure 3.7. A: Reattachment of the gluteus minimus. B: Suturing of the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis.

Figure 3.7. A: Reattachment of the gluteus minimus. B: Suturing of the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis.

femoral neck, and proximal femur is useful for capsular incisions,

reduction of femoral neck fractures, upper femoral osteotomies, and

internal fixation of proximal femoral fractures. One advantage of this

approach is that it exposes the femoral neck, thereby allowing the

surgeon to accurately identify femoral anteversion.

-

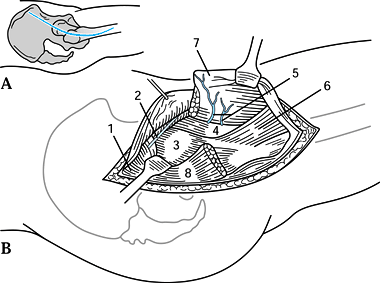

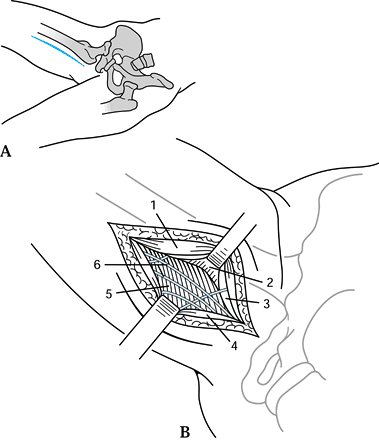

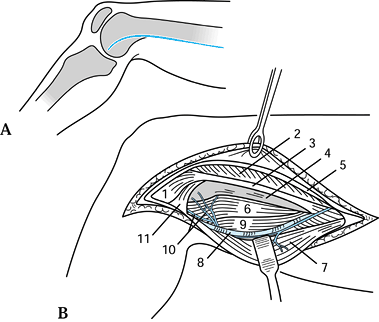

At a point 2–3 cm posterior to the

anterosuperior iliac spine, begin the incision directed toward the

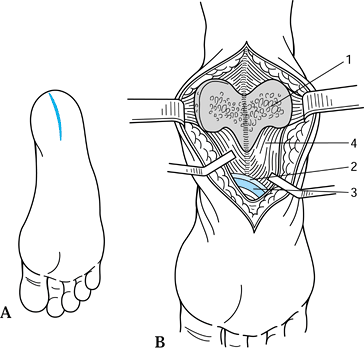

midportion of the greater trochanter (Fig. 3.8A). Then angle the incision into a straight lateral orientation and proceed distally 10–15 cm.![]() Figure 3.8. Watson-Jones anterolateral approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B: The vastus lateralis is retracted anteriorly, as is the tensor fascia, exposing the anterior hip capsule. 1, Gluteus medius; 2, nerve to tensor fasciae latae; 3, hip joint capsule; 4, iliopsoas; 5, lateral circumflex femoral vessels; 6, vastus intermedius; 7, vastus lateralis (reflected); 8, greater trochanter. (From Schlumpf R. Proximal Femur: Lateral Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:115–121.)

Figure 3.8. Watson-Jones anterolateral approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B: The vastus lateralis is retracted anteriorly, as is the tensor fascia, exposing the anterior hip capsule. 1, Gluteus medius; 2, nerve to tensor fasciae latae; 3, hip joint capsule; 4, iliopsoas; 5, lateral circumflex femoral vessels; 6, vastus intermedius; 7, vastus lateralis (reflected); 8, greater trochanter. (From Schlumpf R. Proximal Femur: Lateral Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:115–121.) -

Identify the interval between the gluteus

medius and tensor fascia lata, best done at a point halfway between the

anterosuperior iliac spine and the greater trochanter. -

Place a pointed retractor posterior to

the tensor fascia lata with the point on the anterior rim of the

acetabulum. With posteriorly directed retraction of the gluteus medius,

expose the hip capsule (Fig. 3.1B). Chapman

(personal communication, 1993) facilitates this exposure by first

splitting the fascia lata distally. As the dissection is carried

proximally, the interval between the bellies of the tensor fascia lata

and gluteus medius muscles becomes more obvious. Thus it is easier to

identify the superior gluteal artery and nerve and avoid wandering in

the wrong interval. -

Incise the hip capsule in line with the

femoral neck in its midportion. To gain greater exposure to the femoral

neck and head, extend the capsular incision perpendicular to the plane

of the initial incision by dissecting the capsule off the

intertrochanteric ridge superiorly and inferiorly. -

For greater exposure of the proximal

femoral shaft, detach the vastus lateralis from the vastus tubercle

portion of the anterior intertrochanteric line. From this point

distally, split the vastus longitudinally or retract it anteriorly,

P.33

and detach it from the insertion on the most proximal portion of the linea aspera to gain access to the femoral shaft. -

For wider exposure to the intracapsular

femur, detach the anterior fibers of the gluteus medius from the

anterior one half of the tendinous insertion on the greater trochanter,

leaving a cuff of tendon on the trochanter for later repair.

exposure of the femoral neck and acetabulum call for the Harris

anterolateral approach to the hip joint. This approach is useful in

that the hip can be dislocated anteriorly or posteriorly.

-

Place the patient in the lateral position

with the unaffected hip facing down. Bean bags, kidney rests, or “hip

positioners” attached to the operating table help to maintain the true

lateral position. Abduct the affected limb 60° and keep the hip

extended and the knee flexed. A Mayo stand with a pillow and sterile

cover relieves the assistants of considerable burden in maintaining

this position. -

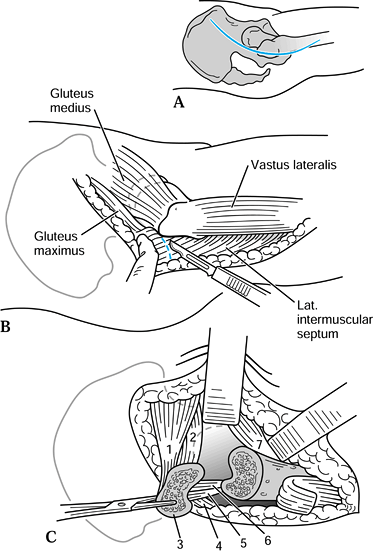

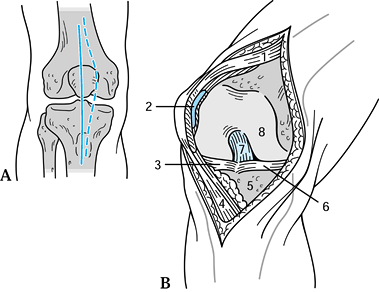

Make a lazy U–shaped skin incision

beginning 5 cm posterior and 2 cm proximal to the anterosuperior iliac

spine. Curve the incision distally toward the posterior greater

trochanter (Fig. 3.9A), and extend it distally and slightly anteriorly for a distance of 15 cm. Figure 3.9. Harris anteriolateral approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B:

Figure 3.9. Harris anteriolateral approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B:

The anterior aspect of the gluteus maximus insertion on the iliotibial

tract is incised 1.5 cm posteriorly to allow greater exposure of the

posterior aspect of the greater trochanter. C: The trochanter is osteotomized, exposing the external rotators and hip capsule. 1, Gluteus medius; 2, gluteus minimus; 3, greater trochanter (osteotomized); 4, piriformis; 5, obturator internus; 6, obturator externus; 7, iliopsoas. (From Rosenthal S. Surgical Approaches. In: Crenshaw AH, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:70.) -

Working distally to proximally, divide

the iliotibial band in line with its fibers. At the level of the

trochanter, direct the fascia lata incision 1 cm anterior to the

insertion of the gluteus medius on the greater trochanter, and continue

the incision of this layer anteriorly in line with the incision. -

To provide posterior exposure, make an

oblique incision in the deep surface of the posteriorly reflected

fascia lata and into the substance of the gluteus medius for a distance

of 5 cm (Fig. 3.9B). Place a pointed Hohmann

retractor on the anterior acetabulum to retract the anterior part of

the tensor fascia lata and iliotibial band anteriorly. -

Sharply dissect the origin of the vastus

lateralis from the vastus tubercle portion of the intertrochanteric

line. Isolate the abductors from the joint capsule anteriorly by blunt

dissection. -

Elevate the periosteum from the proximal

femur transverse to the long axis of the femur at a distance of 3–3.5

cm from the tip of the trochanter. At this point, before osteotomizing

the greater trochanter, the surgeon may choose to predrill or measure

holes for later osteotomy screw or wire fixation. Direct the osteotomy

superiorly and medially toward a point 5 mm lateral to the superior hip

capsular attachment on the femoral neck (Fig. 3.9C). -

Free the superior part of the joint

capsule from the abductors. By virtue of the posterior fascia lata and

gluteus medius incision, posterior exposure is now possible. Divide the

piriformis and external rotators at their femoral insertions. For

arthroplasties, excise the posterior and anterior capsule, as necessary. -

Place a narrow Hohmann or Bennett

retractor deep to the rectus femoris on the anteroinferior iliac spine

to improve visualization anteriorly. To expose the iliopsoas tendon,

flex the hip and rotate it externally. This tendon can be divided and

sutured to a remnant of intact

P.34

anterior

capsule if desired to correct a flexion contracture. The hip can be

dislocated anteriorly to gain access to the entire femoral head and

neck by placing the greater trochanter into the acetabulum. For

exposure of the acetabulum, retract the greater trochanter superiorly

and dislocate the femoral head posteriorly. Maintain the abducted

position of the limb for trochanteric reattachment and wound closure.

access to the posterior femoral neck for bone graft procedures,

posterior drainage of septic joints, or reconstructive procedures of

the proximal femur.

-

Place the patient in the lateral position

with the unaffected side facing down. Bean bags, kidney rests, or “hip

positioners” attached to the operating table are excellent adjuncts for

maintaining the true lateral position. Alternatively, the procedure can

be done with the patient prone. The prone position may be recommended

for certain femoral neck bone grafting procedures. -

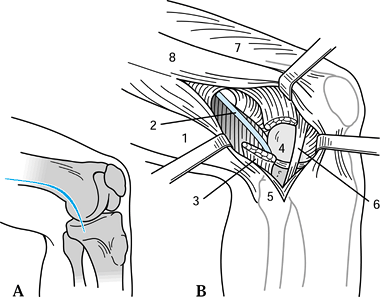

Begin the incision 10 cm distal to the

posterosuperior iliac spine, and extend it laterally and distally in

line with the gluteal fibers (Fig. 3.10A) to

the posterior margin of the greater trochanter. Then carry the incision

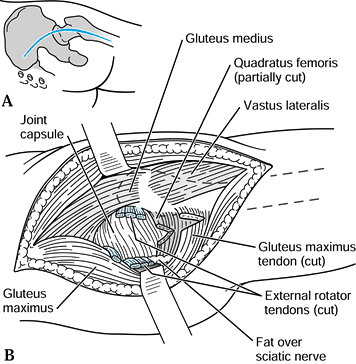

distally for a distance of 15–20 cm in line with the femoral shaft.![]() Figure 3.10. Moore posterior approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B:

Figure 3.10. Moore posterior approach to the hip. A: Skin incision. B:

Detachment and retraction of the external rotators; incision of the hip

capsule. (From Thomas HA. The Hip. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:342.) -

Divide the thick fascia lata distally and

the thin gluteal fascia proximally in line with the skin incision.

Divide the deep fibers of the gluteal musculature bluntly using a

finger-spreading technique, preserving the branches of the superior

gluteal nerve and vessels in the proximal dissection. Partially divide

the distal insertion of the fibers of the gluteal musculature from

their femoral insertion to allow distal retraction. Retract in a plane

perpendicular to the gluteal split, and expose the greater trochanter. -

Identify the sciatic nerve in the medial

portion of the wound and carefully protect it. Divide the external

rotators and the tendon of the piriformis at their femoral insertions,

and retract them medially, forming a protective sling over the sciatic

nerve (Fig. 3.10B). Expose the posterior part

of the hip capsule, and incise along the axis of the femoral neck. For

exposure of the femoral neck, dissect the distal insertion of the

capsule from the posterior intertrochanteric ridge. Protect the medial

femoral circumflex artery inferiorly; it supplies the femoral head in

its terminal branch, the lateral epiphyseal artery. For procedures that

require hip dislocation, flex the hip to 90°, keeping the knee flexed,

and externally rotate the thigh.

reduction of congenitally dislocated hips; for resection of small,

primary, benign bone tumors in the region of the lesser trochanter; and

for obturator neurectomies.

-

Position the patient supine, with the

affected hip flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. This position

brings the lesser trochanter closer to the skin surface. -

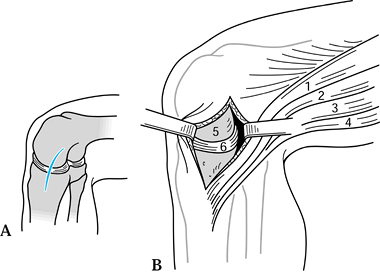

Make a longitudinal incision on the

medial thigh, starting 3 cm distal to the pubic tubercle in line with

the adductor longus, which is easily palpable (Fig. 3.11A).

Develop the plane between the adductor longus and brevis muscles

anteriorly and the adductor magnus and gracilis muscles posteriorly.

The posterior branch of the obturator nerve is visible on the belly of

the adductor magnus; protect it unless it is to be cut to relieve

muscular spasticity. The anterior branch lies on the anterior surface

of the adductor brevis and is protected by retraction of this muscle.

The lesser trochanter is visible in the base of the wound (Fig. 3.11B).

Isolate the iliopsoas tendon with blunt dissection. It is then easily

transected, allowing greater exposure of the medial hip capsule. Figure 3.11. Ludloff medial approach to the hip. A: Skin incision; patient positioning. B:

Figure 3.11. Ludloff medial approach to the hip. A: Skin incision; patient positioning. B:

The adductor longus is retracted anteriorly, exposing the lesser

trochanter, inferior hip capsule, and posterior branches of the

obturator nerve. 1, Adductor longus; 2, lesser trochanter; 3, adductor brevis; 4, gracilis; 5, adductor magnus; 6, obturator nerve, posterior branch. (From Thomas HA. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:349, 351.)

useful for tumor resection or internal fixation of shaft fractures. It

is the preferred approach to the femoral shaft for most situations.

-

Position the patient in the lateral or the supine position.Elevate the hindquarter 30° to 45° with a pad under the buttock.

-

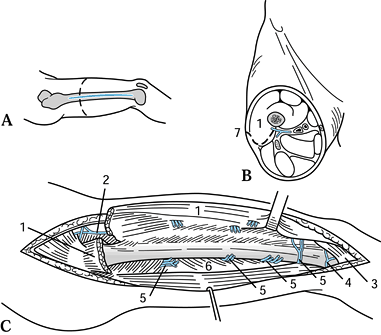

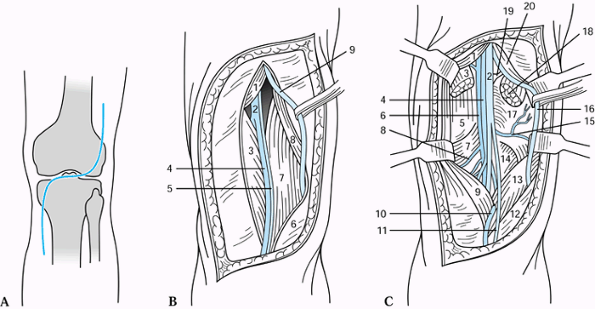

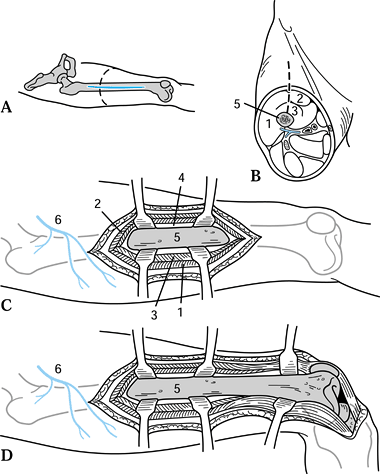

Make an incision of the necessary length along a line between the greater trochanter and the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 3.12A). Divide the superficial and deep fascia in line with the incision.

![]() Figure 3.12. Lateral approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B: Plane of dissection shown in cross section. C: The vastus lateralis has been mobilized anteriorly and the perforating vessels ligated, exposing the entire femoral shaft. 1, Vastus lateralis; 2, lateral circumflex femoral vessels; 3, joint capsule (knee); 4, lateral superior genicular artery; 5, perforating arteries, posterior vastus branches; 6, lateral intermuscular septum; 7, incision. (From Schlumpf R. Femoral Shaft: Lateral Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:125-127.)

Figure 3.12. Lateral approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B: Plane of dissection shown in cross section. C: The vastus lateralis has been mobilized anteriorly and the perforating vessels ligated, exposing the entire femoral shaft. 1, Vastus lateralis; 2, lateral circumflex femoral vessels; 3, joint capsule (knee); 4, lateral superior genicular artery; 5, perforating arteries, posterior vastus branches; 6, lateral intermuscular septum; 7, incision. (From Schlumpf R. Femoral Shaft: Lateral Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:125-127.) -

For the preferred posterolateral

approach, retract the vastus lateralis anteriorly, and dissect the

muscle off the lateral intermuscular septum where it attaches to the

linea aspera of the femur (Fig. 3.12B). Make the incision 2–3 cm more posterior to help with this part of the exposure. -

Carefully identify, ligate, and divide

the perforating branches of the profunda femoris in the middle third of

the femoral shaft (Fig. 3.12C). If the surgeon

inadvertently transects at the level of the septum, these vessels can

retract to the medial side of the septum, producing impressive

hemorrhage. -

For the lateral approach, divide the

vastus lateralis and intermedius in line with the incision. As in the

posterolateral approach, identify and ligate the perforating branches

of the profunda femoris with the descending branch of the lateral

femoral circumflex artery in the proximal third of the femoral shaft,

and the superolateral geniculate artery in the distal third.

useful if poor skin or violation of muscle compartments by tumor render

the posterolateral or lateral approaches impossible. It is not the

exposure of choice for most conditions, because

postoperative

quadriceps adhesions can result, particularly if the knee cannot be

mobilized immediately after surgery. Combined with an anterolateral

approach to the knee joint, it becomes a versatile and wide exposure

for T-type intra-articular fractures of the distal femur. Meticulous

layered closure and immediate mobilization of the knee joint prevents

loss of motion due to quadriceps adhesions. M. W. Chapman, the editor

of this book, prefers this approach for comminuted intra-articular

fractures of the distal femur (personal communication, 1999).

-

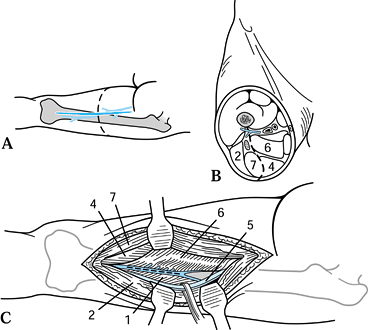

Make a skin incision along the line

between the anterosuperior iliac spine and the lateral border of the

quadriceps tendon as it inserts into the patella. Incise the

superficial and deep fascia in line with the incision, and develop the

interval between the rectus femoris medially and the vastus lateralis

laterally (Fig. 3.13A). This interval is easily identified proximally. Figure 3.13. Anterolateral approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B:

Figure 3.13. Anterolateral approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B:

Plane of dissection between the rectus femoris and vastus lateralis

through the vastus intermedius. (From Schlumpf R. Distal Femur: Lateral

Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:132-135.) C:

Retraction of the vastus intermedius and rectus femoris anteriorly and

vastus lateralis inferiorly exposes the entire femoral shaft. D: The dissection can be carried out distally to expose the articular surface of the distal femur and knee joint. 1, Vastus lateralis; 2, rectus femoris; 3, vastus intermedius; 4, periosteum; 5, femur; 6, lateral circumflex femoral artery. (From Thomas HA. The Femur. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:372.) -

Divide the thinnest and midline portion

of the vastus intermedius in line with its fibers, and expose the femur

by subperiosteal dissection (Fig. 3.13B). The

exposure is best limited to the distal two thirds of the femoral shaft,

because proximally the innervation to the vastus lateralis limits

exposure. -

If it is desirable to expose the

articular condyles and knee, carry the incision through a lateral

parapatellar approach to the knee. The patella can be dislocated

medially (Fig. 3.13C, Fig. 3.13D).

useful only for the middle three fifths of the femoral shaft. It is

probably indicated only for treatment of tumors and exploration of the

sciatic nerve. It can be extended into Henry’s exposure of the sciatic

nerve to provide a comprehensive extensile approach to the posterior

thigh.

-

Position the patient prone on the

operating table, using appropriate bolsters to allow free abdominal and

chest movement. Align the incision with the femur from 5 cm distal to

the gluteal fold to 10 cm proximal to the popliteal crease (Fig. 3.14A). Incise the superficial and deep fascia in line with the skin incision, avoiding the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve.![]() Figure 3.14. Posterior approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B:

Figure 3.14. Posterior approach to the femoral shaft. A: Skin incision and level of cross section. B:

Plane of dissection between the semimembranosus and adductor magnus and

the semitendinosus. (From Schlumpf R. Femoral Shaft: Lateral Approach.

In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:124.) C: Lateral retraction of the sciatic nerve. 1, Biceps femoris, short head; 2, biceps femoris, long head; 3, linea aspera; 4, semimembranosus; 5, sciatic nerve; 6, adductor magnus; 7, semitendinosus. (From Thomas HA. The Femur. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:376.) -

Identify the interval between the biceps

femoris and the vastus lateralis. In the proximal part of the

dissection, detach the short head of the biceps femoris sharply from

the linea aspera. Then reflect it medially (Fig. 3.14B) to expose the femoral shaft. -

In the distal half of the wound, retract the long head of the biceps laterally to expose the sciatic nerve (Fig. 3.14C).

Gently retract the sciatic nerve laterally to expose the femur. Take

the adductor magnus and biceps femoris off the linea aspera sharply.

For sciatic nerve explorations, begin the deep dissection in this

distal half of the wound.

the femoral artery; usually such arterial injuries are associated with

fractures. It is also occasionally useful for medial internal fixation

of fractures or osteotomies.

-

With the patient supine and the hip

flexed and externally rotated, position the knee in flexion. Begin the

incision at the mid thigh and extend it distally to 5 cm distal to the

adductor tubercle (Fig. 3.15A). Carefully

incise the superficial fascia and the deep fascia, which is quite thin

in this region; at the same time, avoid the saphenous vein and nerve,

which are superficial. Figure 3.15. Medial approach to the distal femur. A: Skin incision. B:

Figure 3.15. Medial approach to the distal femur. A: Skin incision. B:

The intramuscular septum falls posteriorly with the knee in flexion.

Mobilize it anteriorly or take it down and reattach it to gain exposure

to the midline of the distal femur. 1, Medial condyle, femur; 2, vastus medialis muscle; 3, adductor tendon; 4, femoral shaft; 5, deep fascia; 6, intramuscular septum; 7, sartorius; 8, saphenous nerve and superior geniculate artery; 9, biceps femoris muscle; 10, popliteal vessels; 11, gastrocnemius muscle. (From Stead Z. Medial Route Extended to Femoropopliteal Trunks to the Shaft. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:216.) -

Distally identify the anterior edge of

the sartorius, which falls posteriorly with progressive knee flexion.

The adductor tendon is visible. Mobilize it anteriorly or take it down

and reattach it to gain exposure to the midline of the distal femur. -

Incise its fascia with care posteriorly (Fig. 3.15B).

Posterior to the adductor, the popliteal vessels and, more deeply, the

tibial branch of the sciatic nerve are visible. Position internal

fixation plates anteriorly to the adductor tubercle after performing

subperiosteal dissection, taking care to avoid violating the joint

capsule.

combination of approaches that allow the sciatic nerve to be explored

from its extrapelvic origin to the popliteal fossae (2).

-

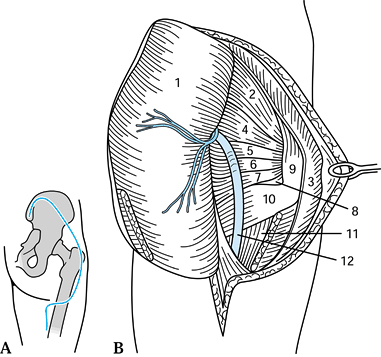

Position the patient prone and outline the “question mark” incision (Fig. 3.16A).

Avoid injury to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh as it exits

from beneath the gluteus maximus and runs distally down the thigh.

After incising the deep gluteal fascia, develop the interval between

the gluteus medius and maximus.![]() Figure 3.16. Henry’s exposure of the sciatic nerve. A: Skin incision. B: Mobilization of the gluteal mass medially on its neurovascular bundle to expose the sciatic nerve. 1, Gluteus maximus; 2, gluteus medius; 3, iliotibial tract; 4, piriformis; 5, gemellus superior; 6, obturator internus; 7, gemellus inferior; 8, obturator externus; 9, greater trochanter; 10, quadratus femoris; 11, adductor magnus; 12, sciatic nerve. (From Stead Z. Structures Under the Gluteal Lid. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:189.)

Figure 3.16. Henry’s exposure of the sciatic nerve. A: Skin incision. B: Mobilization of the gluteal mass medially on its neurovascular bundle to expose the sciatic nerve. 1, Gluteus maximus; 2, gluteus medius; 3, iliotibial tract; 4, piriformis; 5, gemellus superior; 6, obturator internus; 7, gemellus inferior; 8, obturator externus; 9, greater trochanter; 10, quadratus femoris; 11, adductor magnus; 12, sciatic nerve. (From Stead Z. Structures Under the Gluteal Lid. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:189.) -

Cut the gluteus maximus free from its insertion into the

P.38

femur, and fold the entire gluteus maximus flap back medially on its

neurovascular bundle. The sciatic nerve, proximally exposed, is easily

traced to the superior margin of the long head of the biceps femoris,

where it passes deeply to this muscle (Fig. 3.16B). From this point distally, the entire exposure is as previously described for the posterior approach.

the knee joint for most intraarticular problems. The list includes

meniscectomy (total or partial), removal of loose bodies, stabilization

of osteochondral fractures, ligament or meniscal repair, drainage

procedures, ligament reconstructions, fixation or excision of patella

fractures, and synovectomy. The anteromedial deep dissection can be

combined with a straight anterior skin incision (Fig. 3.17)

for more extensive exposure for these conditions and for total knee

replacement. Use it whenever possible, because it gives the best

possible route for reexploration, whenever repeat procedures may be

required or when later reconstructive procedures are anticipated.

|

|

Figure 3.17. Anterior and anteromedial exposure to the knee. A: Skin incisions; anterior (solid line), anteromedial (dotted line). B: The deep exposure for the two approaches is the same. 1, Quadriceps tendon; 2, articular surface, patella; 3, lateral meniscus; 4, patellar ligament; 5, medial tibial plateau; 6, medial meniscus; 7, anterior cruciate ligament; 8, medial femoral condyle. (From Thomas HA. The Knee. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:376.)

|

-

For the anterior incision, make a

straight incision midline extending 10 cm above the patella to 3 cm

below the tibial tubercle (Fig. 3.17A). For the

anteromedial incision, begin on the medial side of the quadriceps

tendon, 5–7 cm above the patella. Curve the incision around the

superomedial border of the patella, then distally to the medial side of

the tibial tubercle. Preserve the infrapatellar branches of the

saphenous nerve whenever possible. -

The deep dissection is identical for both procedures (Fig. 3.17B).

Divide the vastus medialis muscle from the quadriceps tendon on the

medial side, leaving a 5 mm cuff of tendon on the muscle side. Extend

the quadriceps tendon split proximally to the extent of the skin

incision. Divide the capsule and synovium together, 5 mm lateral to the

medial border of the patella. -

Carry this deep dissection down to the

medial side of the tibial tubercle. Flex the knee, completely divide

the synovium in line with the capsular incision, and dislocate the

patella laterally (Fig. 3.17B) to expose the

notch of the femur, revealing the anterior cruciate and medial

meniscus. Carefully preserve the patellar tendon insertion if the

patella is to be inverted for joint replacement procedures.

Subperiosteal dissection of the medial one half of the tendon at the

joint line will decrease the tension in the tendon during this maneuver.

exposure to all joint structures as do the anteromedial and the

anterior approaches. It is useful for exposure of the anterior two

thirds of the lateral meniscus, for isolated lateral compartment

reconstructive procedures, and for internal fixation of lateral tibial

plateau or femoral condyle fractures, particularly if combined with

anterolateral exposure of the femoral shaft.

-

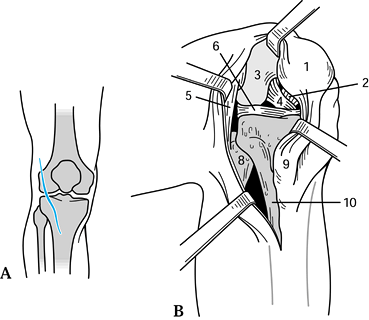

With the knee in slight flexion, begin

the incision 10 cm proximal to the patella in line with the insertion

of the vastus lateralis on the quadriceps tendon (Fig. 3.18A).

Curve the incision gently at the lateral patellar border, and extend it

distally to the level of the tibial tubercle lateral to it. The deep

capsular incision is 5 mm lateral to the insertion of the vastus

lateralis on the quadriceps tendon.![]() Figure 3.18. Anterolateral approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: Medial subluxion of the patella exposes the anterior cruciate and lateral meniscus. 1, Patella; 2, posterior cruciate ligament; 3, lateral femoral condyle; 4, anterior cruciate ligament; 5, fibular collateral ligament; 6, lateral meniscus; 7, transverse ligament; 8, fibular head; 9, tibial tuberosity; 10, lateral tibial surface. (From McConnell J. Surgical Approaches. In: Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:44.)

Figure 3.18. Anterolateral approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: Medial subluxion of the patella exposes the anterior cruciate and lateral meniscus. 1, Patella; 2, posterior cruciate ligament; 3, lateral femoral condyle; 4, anterior cruciate ligament; 5, fibular collateral ligament; 6, lateral meniscus; 7, transverse ligament; 8, fibular head; 9, tibial tuberosity; 10, lateral tibial surface. (From McConnell J. Surgical Approaches. In: Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:44.) -

Incise the synovium in the same plane, and sublux the patella medially to expose the anterior cruciate and lateral meniscus (Fig. 3.18B). The patella cannot be inverted medially because of the strong medial orientation of the quadriceps attachments.

frequently used for lateral extraarticular ligament reconstructions or

in combination with an anteromedial approach for an

intraarticular

reconstruction. It is also useful for exposure of the posterior half of

the lateral meniscus and for explorations of the common peroneal nerve

and its branches.

-

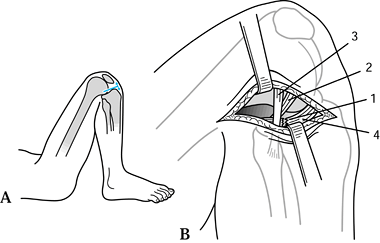

With the knee flexed 90°, make a gently curved 15 cm incision (dotted line in Fig. 3.19A)

just anterior to the biceps femoris tendon and fibular head to expose

the fascia lata. Keep the position of the common peroneal nerve (Fig. 3.19B) in mind constantly. Figure 3.19. Henderson’s posterolateral approach to the knee. A: Skin incision can be extended proximally (dotted line) for exposure of the fascia lata. B: Exposure of the common peroneal nerve and fibular collateral ligament. 1, Biceps femoris; 2, common peroneal nerve; 3, lateral head of gastrocnemius (cut); 4, lateral femoral condyle; 5, fibular head; 6, fibular collateral ligament; 7, vastus lateralis; 8, iliotibial band.

Figure 3.19. Henderson’s posterolateral approach to the knee. A: Skin incision can be extended proximally (dotted line) for exposure of the fascia lata. B: Exposure of the common peroneal nerve and fibular collateral ligament. 1, Biceps femoris; 2, common peroneal nerve; 3, lateral head of gastrocnemius (cut); 4, lateral femoral condyle; 5, fibular head; 6, fibular collateral ligament; 7, vastus lateralis; 8, iliotibial band. -

Proximally, follow the anterior surface

of the lateral intramuscular septum back to the linea aspera. At this

point, the nerve is just posterior to the dissection. -

Expose the lateral femoral condyle and

fibular collateral ligament origin in the midportion of the wound. The

lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle is evident posteriorly and

protects the nerve at that level. The posterior half of the lateral

meniscus is visible posterior to the fibular collateral ligament with

the popliteus tendon coming up from posteroinferior to the

posterior-midmeniscus region (Fig. 3.19B). This

tendon may be retracted posteriorly as the capsule and synovium are

opened through a longitudinal incision above the menisci.

lateral meniscus. Resection of the meniscus does not require release of

the fibular collateral ligament.

-

Position and drape the patient to allow

full flexion; more than 100° of flexion is helpful. Make the incision

parallel to the lateral meniscus, beginning anteriorly at the lateral

border of the patellar tendon (Fig. 3.20A). Its posterior limit is at a line between the fibular head and lateral femoral condyle. Divide the subcutaneous

P.40

tissue in line with the incision, and divide the iliotibial band in line with its fibers.![]() Figure 3.20. Bruser’s posterolateral approach to the knee. A: Line of skin incision parallel to the lateral meniscus located halfway between the patella and tibial tubercle (arrow). B: Division of the iliotibial band. 1, Iliotibial band; 2, popliteal tendon; 3, fibular collateral ligament; 4, torn lateral meniscus. (From McConnell J. Surgical Approaches. In: Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol. 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:47.)

Figure 3.20. Bruser’s posterolateral approach to the knee. A: Line of skin incision parallel to the lateral meniscus located halfway between the patella and tibial tubercle (arrow). B: Division of the iliotibial band. 1, Iliotibial band; 2, popliteal tendon; 3, fibular collateral ligament; 4, torn lateral meniscus. (From McConnell J. Surgical Approaches. In: Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol. 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:47.) -

The knee must be flexed during this part

of the dissection to prevent transection of the iliotibial band. Divide

the iliotibial band along the lines of its fibers to Gurde’s tubercle,

expose the fibula, collateral ligament, and the torn lateral meniscus

central to it. The relaxed fibular collateral ligament must be

protected posteriorly when this incision is made (Fig. 3.20B).

The inferolateral geniculate artery should be ligated, because it lies

at the posterolateral corner of the meniscus. Incise the synovium,

allowing complete exposure of the meniscus.

is useful for exposure of the posteromedial corner of the knee joint

for posterior meniscal horn resections, posteromedial corner

reconstructions, or repair or reconstruction of the posterior cruciate

ligament.

-

Position the patient supine with the hip in external rotation and the knee flexed 90°.

-

Make a 10 cm incision from the adductor

tubercle along the course of the tibial collateral ligament and

anterior to the pes anserine tendons (Fig. 3.21A). Figure 3.21. Henderson’s posteromedial approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: The deep dissection is carried out anterior to the pes anserine tendons. 1, Sartorius; 2, gracilis; 3, semimembranosus; 4, semitendinosus; 5, medial femoral condyle; 6, medial meniscus. (From Thomas HA. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:400, 415.)

Figure 3.21. Henderson’s posteromedial approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: The deep dissection is carried out anterior to the pes anserine tendons. 1, Sartorius; 2, gracilis; 3, semimembranosus; 4, semitendinosus; 5, medial femoral condyle; 6, medial meniscus. (From Thomas HA. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:400, 415.) -

Incise the oblique portion of the tibial collateral ligament in line with the tendons, and also incise the capsule below (Fig. 3.21B).

This incision exposes the medial meniscus and allows access to the

posteromedial compartment. For capsular and posterior cruciate

reconstructions, it is necessary to develop the interval between the

capsule and the pes anserine tendons and semimembranosus. -

Retract the hamstrings and medial head of

the gastrocnemius muscle posteriorly. For wider exposure, take down the

origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius.

it provides invaluable exposure of the posterior neurovascular

structures and joint capsule. Indications for its use include exposure

of the popliteal neurovascular structures, posterior cruciate ligament

repairs, release of posterior knee contractures, and resection of

popliteal masses.

-

Position the patient prone. Initiate an S-shaped incision (Fig. 3.22A)

with the superior arm lateral and the transverse portion at the level

of the posterior crease (orient the incision transversely along the

flexion crease and direct it superolaterally and inferomedially).

Carefully incise the popliteal fascia in the midline.![]() Figure 3.22. Posterior approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: A linear split of the deep fascia. 1, Semimembranosus; 2, popliteal vein; 3, medial head of gastrocnemius; 4, small saphenous vein; 5, medial sural cutaneous nerve; 6, popliteal fascia; 7, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 8, biceps femoris; 9, common peroneal nerve. C: Sectioning of the gastrocnemius heads. 1, Semimembranosus; 2, tibial nerve; 3, medial head of gastrocnemius; 4, popliteal vein; 5, posterior joint capsule; 6, popliteal artery; 7, oblique popliteal ligament; 8, medial inferior genicular artery; 9, medial head of gastrocnemius; 10, small saphenous vein; 11, medial sural cutaneous nerve; 12, fascia; 13, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 14, plantaris; 15, lateral inferior genicular artery; 16, common peroneal nerve; 17, arcuate ligament; 18, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 19, plantaris; 20, biceps femoris. (From Thomas HA. The Knee. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:431.)

Figure 3.22. Posterior approach to the knee. A: Skin incision. B: A linear split of the deep fascia. 1, Semimembranosus; 2, popliteal vein; 3, medial head of gastrocnemius; 4, small saphenous vein; 5, medial sural cutaneous nerve; 6, popliteal fascia; 7, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 8, biceps femoris; 9, common peroneal nerve. C: Sectioning of the gastrocnemius heads. 1, Semimembranosus; 2, tibial nerve; 3, medial head of gastrocnemius; 4, popliteal vein; 5, posterior joint capsule; 6, popliteal artery; 7, oblique popliteal ligament; 8, medial inferior genicular artery; 9, medial head of gastrocnemius; 10, small saphenous vein; 11, medial sural cutaneous nerve; 12, fascia; 13, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 14, plantaris; 15, lateral inferior genicular artery; 16, common peroneal nerve; 17, arcuate ligament; 18, lateral head of gastrocnemius; 19, plantaris; 20, biceps femoris. (From Thomas HA. The Knee. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:431.) -

linear split of the deep fascia exposes

the common peroneal nerve, the popliteal vein, and two heads of the

gastrocnemius. Identify the sural nerve as it rests in the midline in

the distal portion of the wound, and trace it proximally until it leads

you to the tibial component of the sciatic nerve (Fig. 3.22B). -

Identify the common peroneal nerve from

proximal to distal as it runs along the posterior border of the biceps

femoris. The popliteal vein lies over the tibial nerve at the level of

the gastrocnemius muscle heads. The popliteal artery lies deep and

medial to the tibial nerve. There are five geniculate arteries that

limit retraction of the artery. One of the branches may have to be

ligated, depending on the direction that the dissection needs to take. -

To reach the posteromedial or

posterolateral corners of the joint section, the medial head or lateral

head of the gastrocnemius muscle can be sectioned, leaving a tendinous

cuff to repair (Fig. 3.22C). In this way, the

entire posterior capsule (popliteal artery, tibial nerve, and deep

capsular structures) in its medial and lateral extent can be exposed.

The capsule must be opened transversely to expose the posterior

cruciate ligament in the midline.

reduction of medial or lateral tibial plateau fractures, or for

resection of tumors or infectious processes involving this region of

the tibia.

-

With the knee gently flexed, make the

distal half of the straight anterior approach to the knee joint,

beginning at the superior pole of the patella. After incising the

subcutaneous tissue in line with the incision, subcutaneously dissect

in the lateral or medial direction (or both), with the knee flexed to

90° (Fig. 3.23). Figure 3.23. Anterior approach to the proximal tibial shaft. The skin incision of the anterior approach to the knee (see Fig. 3.17) can be extended distally to expose the proximal tibia. The pes anserine tendons can be released subperiosteally (dotted line) to expose the medial tibial condyle. 1, Quadriceps tendon; 2, quadriceps femoris, vastus medialis; 3, suprapatellar recess; 4, infrapatellar fatty body of Hoffa; 5, tibial tuberosity; 6, anterior cruciate ligament; 7, posterior cruciate ligament; 8, anterior horn, medial meniscus; 9,

Figure 3.23. Anterior approach to the proximal tibial shaft. The skin incision of the anterior approach to the knee (see Fig. 3.17) can be extended distally to expose the proximal tibia. The pes anserine tendons can be released subperiosteally (dotted line) to expose the medial tibial condyle. 1, Quadriceps tendon; 2, quadriceps femoris, vastus medialis; 3, suprapatellar recess; 4, infrapatellar fatty body of Hoffa; 5, tibial tuberosity; 6, anterior cruciate ligament; 7, posterior cruciate ligament; 8, anterior horn, medial meniscus; 9,

pes anserinus. (From Schlumpf R. Knee Joint and Proximal Tibia: Lateral

Parapatellar Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R,

eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:151.) -

To gain exposure medially, elevate the

pes anserine insertion and superficial portion of the medial collateral

ligament subperiosteally. Divide the meniscotibial ligament (i.e., the

deep portion of the medial collateral ligament) beneath the meniscus,

allowing visualization of the tibial joint surface. Leave enough tissue

attached to the tibia to allow reattachment of the meniscus. -

To gain exposure laterally, open the

joint capsule lateral to the patellar tendon. Elevate the musculature

of the anterior compartment subperiosteally posterior to the level of

the fibular collateral ligament. Elevate Gurde’s tubercle with an

osteotome or reflect the iliotibial band insertion to allow more

complete exposure for application of plates to the proximal lateral

tibia. Examine the joint surface by incising the meniscotibial

attachments of the anterior half of the lateral meniscus.

-

Position the patient laterally with the

affected limb up. Make the skin incision in line with the fibula

distally (to trace the superficial branch of the peroneal nerve) and

biceps femoris proximally, curving posteriorly at the joint line at an

angle of 45° (Fig. 3.24A).![]() Figure 3.24. Henry’s exposure of the peroneal nerve and proximal fibula. A: Skin incision. 1, Common peroneal nerve; 2, head of fibula. B:

Figure 3.24. Henry’s exposure of the peroneal nerve and proximal fibula. A: Skin incision. 1, Common peroneal nerve; 2, head of fibula. B:

The peroneal muscles have been divided transversely and retracted

anteriorly to expose the motor divisions of the deep peroneal nerve

proximally. 1, Common peroneal nerve (lat. popliteal); 2, head of fibula; 3, gastrocnemius; 4, soleus; 5, peroneus longus. (From Stead Z. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:293, 295.) -

Identify the common peroneal nerve where

it lies deep to the biceps tendon in the proximal portion of the wound.

Handle the nerve gently in a rubber sling for retraction. Divide the

deep fascia in line with the nerve,

P.42

developing

a plane of division between the soleus and peroneal muscles. A thin

extension of the peroneus longus origin must be divided at the fibular

neck (Fig. 3.24B).

The nerve is now freed as it curves anteriorly, dividing into muscular

branches. Elevate the peroneal muscles subperiosteally to expose the

upper one half of the fibula.

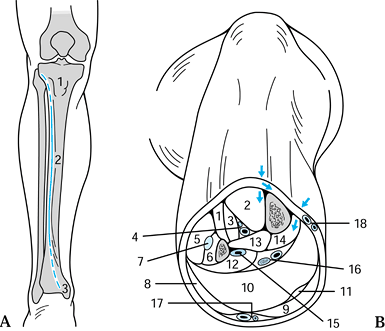

anterior route for osteotomies, internal fixation of fractures or

nonunions, excision of bone tumors, or drainage of infectious processes.

-

Position the patient supine with a pad

under the affected hip to gain slight internal rotation of the leg.

Make the incision 10–15 cm lateral and parallel to the crest of the

tibia (Fig. 3.25). Distally, incise along the

medial border of the anterior tibial tendon to allow intraarticular

exposure, if required. Reflect the skin and periosteum as a single

layer for a medial exposure. Alternatively, lateral subperiosteal

dissection allows retraction of the anterior compartment musculature.

Avoid complete soft-tissue elevation medially and laterally because of

the effect on bone blood supply with this radical exposure. Figure 3.25. Anterior approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision, just lateral to the tibial crest can be extended proximally and distally to expose the entire shaft (dotted lines). 1, Tibial tuberosity; 2, anterior border; 3, medial malleolus. B:

Figure 3.25. Anterior approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision, just lateral to the tibial crest can be extended proximally and distally to expose the entire shaft (dotted lines). 1, Tibial tuberosity; 2, anterior border; 3, medial malleolus. B:

A cross section of the mid calf reveals the plane of dissection to the

lateral surface of the tibia and medially to the fascia of the deep

posterior compartment (arrows). 1, Extensor digitorum; 2, tibialis anterior; 3, extensor hallucis longus; 4, deep peroneal nerve, anterior tibial vessels; 5, peroneus longus; 6, peroneus brevis; 7, superficial peroneal nerve; 8, lateral head, gastrocnemius; 9, medial head, gastrocnemius; 10, soleus; 11, plantaris; 12, flexor hallucis longus; 13, tibialis posterior; 14, flexor digitorum longus; 15, peroneal artery; 16, tibial nerve with posterior tibial vessel; 17, sural nerve with small saphenous vein; 18,

saphenous nerve with great saphenous vein. (From Schlumpf R. Tibial

Shaft: Anterior Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R,

eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:155, 156.)

infection associated with poor anterior skin coverage, elect a

posteromedial approach to the tibial shaft, particularly for the

proximal third. The two-incision method of compartment release also

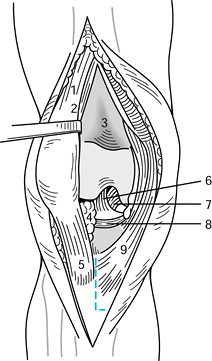

calls for a posteromedial approach for release of the deep posterior

compartment.

-

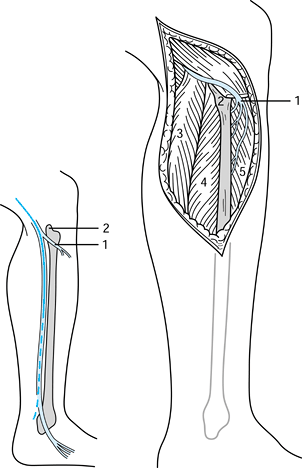

Position the patient supine. Flex the

affected hip and rotate it externally with the knee flexed. Make the

incision in line with the tibia 1–2 cm posterior to the posterior

P.43

border of the tibia (Fig. 3.26A). Protect the saphenous vein and nerve as the subcutaneous tissue is incised in line with the skin incision.![]() Figure 3.26. Posteromedial approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision. B: The deep dissection exposing the fascia. 1, Saphenous nerve; 2, great saphenous vein; 3, crural fascia (superficial); 4, medial condyle, tibia; 5, medial malleolus. (From Schlumpf R. Tibial Shaft: Posteromedial Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:159, 161.)

Figure 3.26. Posteromedial approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision. B: The deep dissection exposing the fascia. 1, Saphenous nerve; 2, great saphenous vein; 3, crural fascia (superficial); 4, medial condyle, tibia; 5, medial malleolus. (From Schlumpf R. Tibial Shaft: Posteromedial Approach. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:159, 161.) -

Divide the superficial compartment fascia

5 mm posterior to the posterior border of the tibia. Carry out the deep

dissection exposing the fascia of the lower leg posterior to the

saphenous nerve and vein. Divide the deep fascia posterior to the

border of the tibia in line with the fibers of the flexor hallucis

longus proximally, flexor digitorum longus in the mid tibia, and

posterior tibialis distally (Fig. 3.26B). Retract the muscles posteriorly, exposing the tibia for the required procedure.

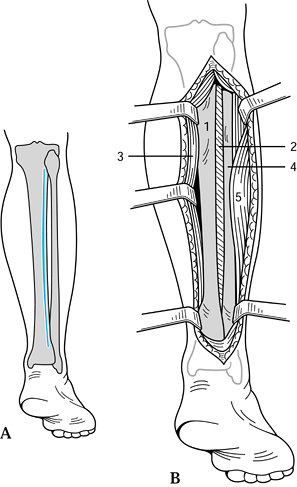

thirds of the tibia and is also useful when the anterior and

anteromedial aspects of the leg have poor soft-tissue coverage. It is

the classic exposure for bone grafting of tibial nonunions.

-

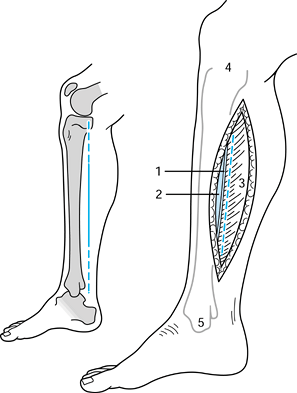

Position the patient prone or on his side with the affected leg up. Make the skin incision (Fig. 3.27A) longitudinally along the lateral border of the gastrocnemius (Fig. 3.27B).

The deep plane is between the peroneal musculature (laterally) and the

superficial and deep posterior compartment musculature (medially),

exposing the intraosseous membrane. Figure 3.27. Harmon posterolateral approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision. B: The deep plane is between the peroneal musculature and the superficial and deep posterior compartment musculature. 1, Tibia; 2, interosseous membrane; 3, soleus and gastrocnemius; 4, fibula; 5, peroneal muscles. (From Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:39.)

Figure 3.27. Harmon posterolateral approach to the tibial shaft. A: Skin incision. B: The deep plane is between the peroneal musculature and the superficial and deep posterior compartment musculature. 1, Tibia; 2, interosseous membrane; 3, soleus and gastrocnemius; 4, fibula; 5, peroneal muscles. (From Edmonson AS, Crenshaw AH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 6th ed, vol 1. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1980:39.) -

Develop the plane between the triceps

surae posteriorly and peroneal muscles anteriorly, exposing the

posterior surface of the fibula. Elevate the flexor hallucis longus

portion of the posterior tibial muscle that originates from the

intraosseous septum, and strip the muscle medially off the posterior

surface of the tibia. Take care in the proximal one third of the wound

to avoid the peroneal artery and vein. The posterior tibial artery and

nerve lie between the flexor hallucis longus and the posterior tibial

muscle and are not easily seen; avoid medial retraction at any place

other than the subperiosteal level. -

With careful subperiosteal dissection,

expose the posterior surface of the middle two thirds of the tibia. In

nonunions for which this approach is most commonly

P.44

used,

callus, scar, and loss of the interosseous membrane can make exposure

in the region of the nonunion difficult. To facilitate exposure, use a

long incision. Expose the interosseous membrane and posterior tibia

first in areas of undisturbed anatomy proximally and distally to the

fracture. Once you have established the proper plane of dissection, it

is fairly easy to expose the nonunion. As you pass medial to the

peroneal muscles and follow the fibula to the interosseous membrane,

the line of dissection is more or less directly anterior. To avoid

perforating the membrane, use a large-key or Cobb elevator to develop

the exposure. In compartment syndrome where compartment fasciotomy is

required, swelling and hematoma can obscure the fascial septae dividing

the anterior, lateral, and posterior compartments. In this situation,

develop the skin and subcutaneous tissue flaps for 2.5–3 cm anteriorly

and posteriorly. In the midportion of the wound, make a transverse

incision through the deep fascia. Identification of the longitudinally

running fascial divisions between the compartments is then easy.

techniques of ankle arthrodesis, internal fixation of distal tibia

(i.e., intraarticular) fractures, joint debridement and removal of

loose bodies, synovectomy, drainage of septic joints, and joint

replacement arthroplasty. Through this approach, both malleoli and the

whole articular surface of the distal tibia can be exposed.

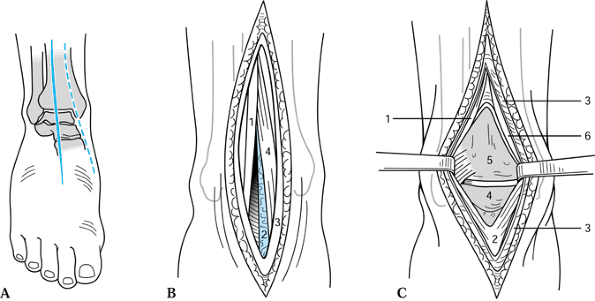

-

Position the patient supine with a folded

sheet under the hip of the affected side in order to internally rotate

the limb. Make a longitudinal 15 cm incision midway between the lateral

and medial malleoli, beginning 10 cm proximal to the joint line (Fig. 3.28A).

Identify and protect the terminal branches of the superficial peroneal

nerve. Incise the deep fascia of the leg in line with the skin

incision. Identify the interval between the extensor hallucis longus

and the extensor digitorum longus. Protect the anterior tibial artery

and the deep peroneal nerve, which are just medial to the extensor

hallucis tendon.![]() Figure 3.28. Anterior approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Division of the extensor retinaculum exposes the extensor hallucis and extensor digitorum tendons. 1, Extensor digitorum longus; 2, deep peroneal nerve and anterior tibial artery (neurovascular bundle); 3, extensor retinaculum; 4, extensor hallucis longus. C: Division of the joint capsule exposes the joint. 1, Extensor digitorum longus; 2, joint capsule of ankle; 3, extensor retinaculum; 4, dome of talus; 5, distal tibia; 6, extensor hallucis longus. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:472, 473.)

Figure 3.28. Anterior approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Division of the extensor retinaculum exposes the extensor hallucis and extensor digitorum tendons. 1, Extensor digitorum longus; 2, deep peroneal nerve and anterior tibial artery (neurovascular bundle); 3, extensor retinaculum; 4, extensor hallucis longus. C: Division of the joint capsule exposes the joint. 1, Extensor digitorum longus; 2, joint capsule of ankle; 3, extensor retinaculum; 4, dome of talus; 5, distal tibia; 6, extensor hallucis longus. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:472, 473.) -

Retract the tendon of the extensor

hallucis medially, taking the neurovascular bundle with it, and the

extensor digitorum longus laterally (Fig. 3.28B).

Distally, at the level of the ankle joint, the neurovascular bundle

crosses the ankle joint behind the extensor hallucis tendon. Mobilize

it carefully as the joint is exposed. -

The capsule is visible beneath the

tendons and can be longitudinally incised or dissected off the distal

tibia as the procedure requires (Fig. 3.28C).

internal fixation of intraarticular fractures of the distal tibia and

medial malleolus. It is an extensile continuation of the anterior

approach to the tibial shaft (Fig. 3.25).

-

Following the course of the tibialis

anterior tendon, curve the incision medially toward the tip of the

medial malleolus, beginning 5 cm above the ankle joint (Fig. 3.29).

Identify the saphenous vein and nerve. Divide the ankle capsule

anterior to the deltoid ligament. Deeply develop the interval between

the tibialis anterior tendon and the medial malleolus. Retract the

tendon laterally, and open the joint by longitudinal incision and

subperiosteal dissection. Figure 3.29. Anteromedial approach to the ankle. 1, Saphenous nerve; 2, saphenous vein. (From Schlumpf R. Medial Malleolus and Distal Tibia. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:167.)

Figure 3.29. Anteromedial approach to the ankle. 1, Saphenous nerve; 2, saphenous vein. (From Schlumpf R. Medial Malleolus and Distal Tibia. In: Rüedi T, von Hochstetter AHC, Schlumpf R, eds. Surgical Approaches for Internal Fixation. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1984:167.)

It is useful for ankle arthrodesis, triple arthrodesis, and talectomy.

-

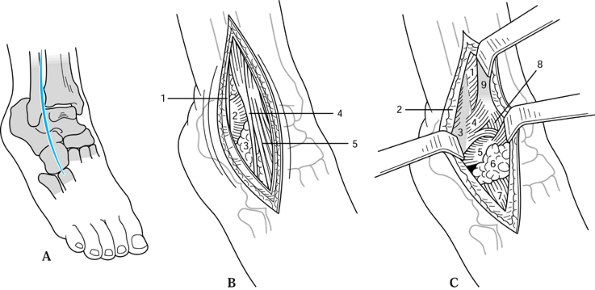

Make a 15 cm incision centered over the distal tibiofibular joint, beginning 5 cm proximal to the ankle joint (Fig. 3.30A).

Curve the incision anteriorly, crossing the ankle joint 2 cm medial to

the tip of the lateral malleolus and extending onto the dorsum of the

foot 2 cm medial to the base of the fifth metatarsal. The incision

crosses the distal tibiofibular joint and angles anteriorly over the

cuboid. Identify and protect the branches of the superficial peroneal

nerve and the saphenous vein.![]() Figure 3.30. Anterolateral approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Deep dissection exposes the sinus tarsi distally. 1, Extensor retinaculum; 2, anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 3, sinus tarsi fat pad; 4, peroneus tertius tendon; 5, extensor digitorum longus tendons. C: Retraction of the tendons exposes the anterior ligament complex of the ankle. 1, Interosseous membrane; 2, extensor retinaculum; 3, distal fibula; 4, anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 5, anterior talofibular ligament; 6, sinus tarsi fat pad; 7, extensor digitorum brevis; 8, joint capsule of ankle; 9, distal tibia. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:497.)

Figure 3.30. Anterolateral approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Deep dissection exposes the sinus tarsi distally. 1, Extensor retinaculum; 2, anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 3, sinus tarsi fat pad; 4, peroneus tertius tendon; 5, extensor digitorum longus tendons. C: Retraction of the tendons exposes the anterior ligament complex of the ankle. 1, Interosseous membrane; 2, extensor retinaculum; 3, distal fibula; 4, anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 5, anterior talofibular ligament; 6, sinus tarsi fat pad; 7, extensor digitorum brevis; 8, joint capsule of ankle; 9, distal tibia. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:497.) -

Develop the interval between the major

peroneal muscles laterally and the extensor muscles anteriorly. The

deep dissection is conducted between the extensor tendons and the

peroneal tendons, exposing the sinus tarsi distally (Fig. 3.30B). -

Retract the extensor tendons medially to expose the ankle capsule (Fig. 3.30C).

The origin of the extensor digitorum brevis can be elevated off the

calcaneus to expose the calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joints and the

fat within the sinus tarsi.

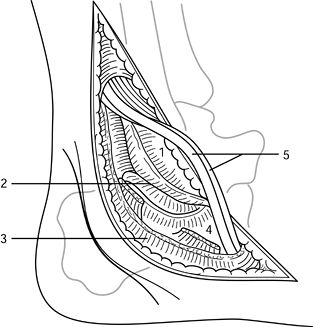

lengthenings, release of the posterior capsule of the ankle, and

exposure of posterior malleolus fractures.

-

The skin incision is based on the medial

border of the triceps surae tendon. Make a 10 cm longitudinal incision

along the posterolateral border of the tendo calcaneus to its insertion

on the calcaneus (Fig. 3.31A). Protect the terminal branches of the sural nerve laterally. Retract the tendo calcaneus medially (Fig. 3.31B).

Lengthening of the tendon can be performed if the procedure requires

it. Divide the areolar tissue anterior to the tendon, and enter the

space between the flexor hallucis longus tendon medially and the

peroneal tendons laterally. Figure 3.31. Posterior approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Deep dissection. 1, Flexor hallucis longus; 2, tibia; 3, ankle joint; 4, talus; 5, subtalar joint; 6, Achilles tendon. (From Stead Z. Exposing the Back of the Distal End of the Tibia. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:270-271.)

Figure 3.31. Posterior approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Deep dissection. 1, Flexor hallucis longus; 2, tibia; 3, ankle joint; 4, talus; 5, subtalar joint; 6, Achilles tendon. (From Stead Z. Exposing the Back of the Distal End of the Tibia. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:270-271.) -

Deep dissection carries the triceps surae

tendon and neurovascular bundle medially. Sharply dissect the lateral

fibers of the flexor hallucis muscle belly from the posterior fibular

border, and develop this interval, exposing the distal tibia, posterior

ankle joint, and posterior talus (Fig. 3.31B). The retracted flexor hallucis longus protects the medial neurovascular structures.

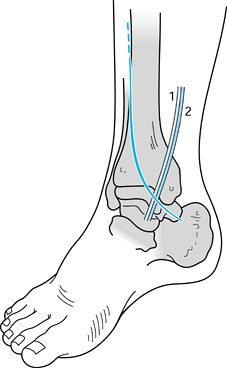

release, exploration of the neurovascular structures, exposure of

posterior malleolus fractures, and tendon lengthenings or transfers.

-

Position the patient supine in the figure-four position, with the affected ankle resting on the opposite thigh.

-

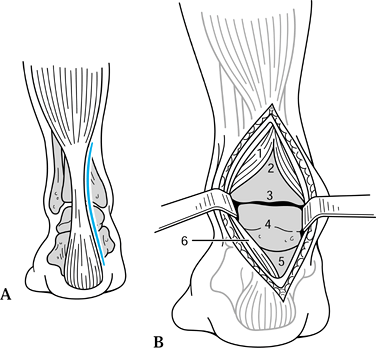

Make a 10 cm longitudinal incision along

the posterior tibial tendon, midway between the medial malleolus and

the tendo calcaneus (Fig. 3.32A). Incise the deep fascia in line with the skin incision (Fig. 3.32B).

Division of the superficial retinaculum exposes the posterior tibial,

flexor digitorum, and flexor hallucis tendons and the posterior tibial

artery and nerve.![]() Figure 3.32. Posteromedial approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Division of the superficial retinaculum. 1, Tibialis posterior; 2, flexor digitorum longus; 3, posterior tibial artery; 4, posterior tibial vein; 5, posterior tibial nerve; 6, flexor hallucis longus; 7, fascia over deep flexor compartment; 8, fibrous pulley over flexor hallucis longus (opened). (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:485, 486.)

Figure 3.32. Posteromedial approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: Division of the superficial retinaculum. 1, Tibialis posterior; 2, flexor digitorum longus; 3, posterior tibial artery; 4, posterior tibial vein; 5, posterior tibial nerve; 6, flexor hallucis longus; 7, fascia over deep flexor compartment; 8, fibrous pulley over flexor hallucis longus (opened). (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:485, 486.) -

Retract the tendon of the flexor hallucis

longus medially after dissecting its lateral fibers off the fibula,

protecting the nerve and artery, and exposing the distal posteromedial

corner of the tibia with the ankle joint capsule.

of posterior malleolus fractures, posterior capsulotomy, posterior

subtalar facet arthrodesis, and tendon lengthenings and transfers.

-

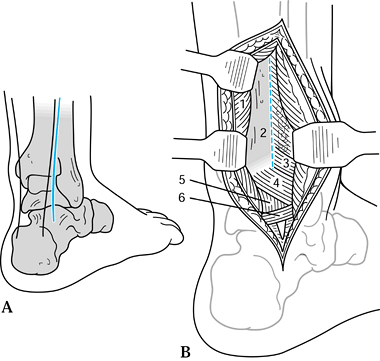

Position the patient prone. Make a

longitudinal 10 cm incision halfway between the posterior border of the

lateral malleolus and the lateral border of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 3.33A).

The lateral border of the triceps surae tendon is a landmark for the

incision. Protect the terminal branch of the sural nerve. The peroneus

brevis consists of a muscle belly in this region, and the peroneus

longus is tendinous. Incise the peroneal retinaculum to allow easy

repair. Figure 3.33. Posterolateral approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: The tendon is retracted medially and the peroneal tendons laterally. 1, Flexor hallucis longus (detached); 2, posterior tibia (incise periosteum); 3, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 4, transverse tibiofibular ligament; 5, posterior joint capsule of ankle; 6, posterior talofibular ligament. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:489, 491, 517.)

Figure 3.33. Posterolateral approach to the ankle. A: Skin incision. B: The tendon is retracted medially and the peroneal tendons laterally. 1, Flexor hallucis longus (detached); 2, posterior tibia (incise periosteum); 3, posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; 4, transverse tibiofibular ligament; 5, posterior joint capsule of ankle; 6, posterior talofibular ligament. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:489, 491, 517.) -

Detach the lateral fibers of the flexor

hallucis longus where they arise from the fibula. Retract this muscle

medially, exposing the posterolateral ligament complex (Fig. 3.33B). Longitudinal subperiosteal dissection exposes the distal tibia, and a linear capsular incision exposes the joint.

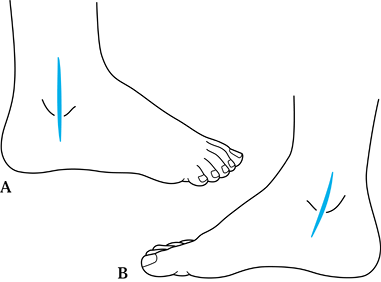

longitudinal skin incisions directly over the malleoli (rather than

curved incisions) permit direct access, are extensile, and have low

morbidity (Fig. 3.34).

|

|

Figure 3.34. Medial and lateral approaches to the ankle. A: Lateral approach. The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum is incised in line with the distal fibula. B:

Medial approach. The incision is placed centrally in the midportion of the medial malleolus. The skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum dissection is in line with the incision. Care must be taken not to divide the saphenous vein. |

the ankle joint allows good exposure of the talonavicular joint,

naviculocuneiform joint, and the first metatarsal–cuneiform joint.

Preserve the dorsal veins and gain direct exposure of the joints of the

mid foot between the tendons of the extensor digitorum. More distal

exposure and deep dissection exposes the bases of the metatarsals.

-

Beginning proximally, make the anterior incision (Fig. 3.35)

in line with the lateral aspect of the second metatarsal, and continue

it distally. Retract the deep peroneal nerve and dorsalis pedis artery

medially with the extensor hallucis longus and tibialis anterior

tendons, exposing the dorsal capsular structures of these joints. Figure 3.35. Anterior approach to the tarsus. This exposure is the distal extension of the anterior approach to the ankle (see Fig. 3.28). (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:472, 513.)

Figure 3.35. Anterior approach to the tarsus. This exposure is the distal extension of the anterior approach to the ankle (see Fig. 3.28). (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:472, 513.) -

Incise the capsule of the involved joint

longitudinally and dissect subperiosteally to expose the joint(s) for

arthrodesis or open reduction of articular surfaces.

|

|

Figure 3.36. Lateral approaches to the tarsus: Kocher and Ollier. A: Skin incisions. 1, Skin incision, Kocher approach; 2,

skin incision, Ollier approach. (From Stead Z. Exposure of the Distal Two-Thirds of the Anterior Neurovascular Bundle. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:277.) B: Deep dissection of the Ollier approach consists of detaching the extensor digitorum brevis and retracting distally exposing the midtarsus. The deep exposure of the Kocher approach is similar in its distal arm but yields better access to the subtalar joint because of its proximal arm. 1, Anterior talofibular ligament; 2, sinus tarsi fat pad; 3, posterior talocalcaneal joint; 4, peronei; 5, calcaneocuboid joint; 6, extensor digitorum brevis; 7, talonavicular joint. (From Thomas HA. The Ankle and Foot. In: Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P, eds. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984:503.) |

-

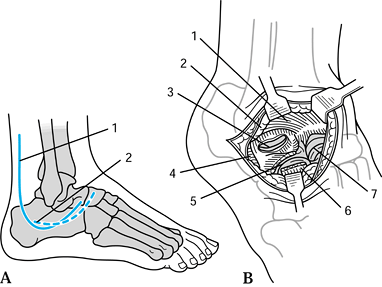

Begin the incision as far proximally as indicated, and

P.49

proceed longitudinally 2 cm posterior to the fibula. Gently curve the

incision anteriorly at the distal flare of the fibula, and reach the

midpoint of the bone 2.5 cm distal to the tip (Fig. 3.36A).

Curve the incision 110° anteriorly in the direction of the

talonavicular joint. Incise the peroneal fascia, and retract the

tendons posteriorly, protecting the sural nerve. -

Divide the talocalcaneal ligament to expose the subtalar joint capsule (Fig. 3.36B).

If possible, avoid dividing the peroneal tendons because of the risk of

scarring within the sheath; if necessary, use a step-cut technique. The

calcaneonavicular joint capsule can be visualized by dissection further

distally, following the peroneus brevis tendon. -

To visualize the articular surface of the

tibia, divide the anterior talofibular ligament and sublux the talus by

varus stress. Divide the capsule and synovium anterior to the fibula,

revealing the articular surfaces of the ankle.

of the talonavicular joint, calcaneocuboid joint, and lateral subtalar

joint. It provides an excellent cosmetic result because of the

abundance of soft tissue in the area.

-

Begin the incision 3 cm posterior to the calcaneocuboid joint (Fig. 3.36A).

Follow the skin lines in an anteromedial direction, and end the

incision over the dorsal aspect of the talonavicular joint. Do not

undermine the skin flaps. -

Detach the origin of the extensor digitorum brevis, and retract it distally (Fig. 3.36B).

If possible, preserve the fat within the sinus tarsi to maintain the

contour of the foot and improve soft-tissue coverage. Medially, retract

the extensor tendons to expose the talonavicular joint. Laterally,

retract the peroneal tendons to fully expose the calcaneocuboid joint

and the posterior facet of the subtalar joint. The joint capsules can

be sharply dissected free in line with the joint surfaces to expose the

joints as necessary.

fractures in the setting of a trimalleolar ankle fracture calls for the

lateral Gatellier and Chastung approach. This method can also be used

for anterolateral osteochondral fractures.

-

Make the incision along the fibula, beginning 15 cm proximally from the tip (Fig. 3.37A).

Curve the incision anteriorly along the pathway of the peroneal tendons

at the tip of the fibula. Expose the fibula subperiosteally. Incise the

periosteal tendon sheath, allowing the tendons to sublux anteriorly,

and turn the fibula distally through the fracture. Figure 3.37. Lateral approach to the tarsus of Gatellier and Chastung. A: Skin incision and level of fibular osteotomy. B:

Figure 3.37. Lateral approach to the tarsus of Gatellier and Chastung. A: Skin incision and level of fibular osteotomy. B:

The fibula has been osteotomized and reflected, based on the

calcaneofibular ligament. Sectioning of the anterior and posterior

talofibular ligaments exposes the ankle joint. (From Stead Z. Exposure

of the Fibula and Nerves Related to It. In: Henry AK, ed. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1973:293.) -

Alternatively, make an osteotomy 7–10 cm

from the fibular tip to allow this same maneuver. The calcaneofibular

and talofibular ligaments serve as the hinge for the fibula to allow

complete exposure of the distal tibia and ankle joint (Fig. 3.37B).

Fix the fracture or osteotomy of the fibula anatomically and rigidly,

and carefully reconstruct the peroneal tendon sheath. The disadvantage

of this approach is devascularization of the distal tibia.

-

Make the incision from an anterior

position located 3 cm anterior and 4 cm inferior to the tip of the

medial malleolus. Extend the incision in a straight line to the medial

border of the Achilles tendon. Divide the deep fascia in line with the

incision, and similarly divide the fat deep to this layer. -

Retract the abductor hallucis inferiorly, and expose the body of the calcaneus subperiosteally. Divide the plan

P.50

tar aponeurosis and strip the muscle origins inferiorly to expose the

plantar surface. Whenever possible, minimize the dissection of the

specialized plantar tissues because of the highly specialized septa

that originate in the body of the calcaneus.

subtalar joint for isolated subtalar arthrodesis or open reduction of

this joint.

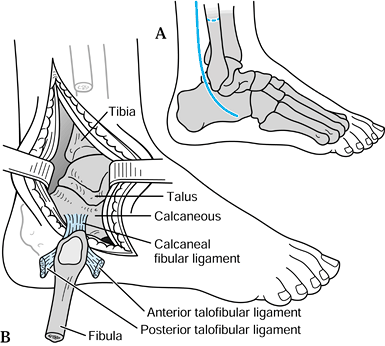

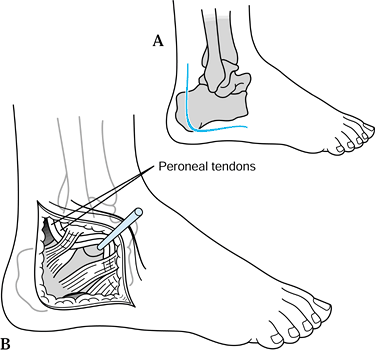

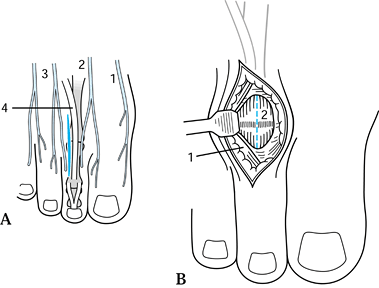

-