CHAPTER 23 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 23 – Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression and Distal Clavicle Excision

Joanne Labriola, MD

The supraspinatus tendon traverses a bony canal or outlet, the size of which is strongly affected by the morphologic features of the undersurface of the anterior acromion and the acromioclavicular joint. During supraspinatus tendon excursion within this outlet, the acromion may apply compressive forces to the tendon. The subacromial bursa serves to mitigate these forces, but repetitive application of these forces or a single macrotraumatic force may traumatize the subacromial bursa and supraspinatus tendon, leading to painful inflammatory changes. This painful process, termed impingement, is hypothesized to compromise the health of the tendon, leading to tearing of the rotator cuff. Therefore, the impingement syndrome includes a spectrum of pathologic changes from subacromial bursitis to full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff (

Box 23-1

). A subacromial decompression may be performed to relieve the forces placed on the rotator cuff tendons or to protect tendon repairs.

Surgical techniques for subacromial decompression have evolved from open to mini-open to all-arthroscopic techniques. Advantages of arthroscopic techniques include decreased trauma to the deltoid, decreased surgical pain, and improved cosmesis.

Shoulder pain due to degenerative changes in the acromioclavicular joint is a common problem. In addition, osteophytes from a hypertrophic degenerative acromioclavicular joint can result in impingement of the underlying rotator cuff. Both problems can be relieved through distal clavicle excision. Distal clavicle excision can be performed at the same time as an arthroscopic subacromial decompression through an indirect approach, or it can be performed alone through direct techniques. In patients with isolated acromioclavicular arthritis, the direct approach is preferred to prevent unnecessary instrumentation of the noninvolved subacromial space.

Preoperative evaluation begins with a thorough history. This includes the position in which symptoms occur, athletic activities, antecedent trauma or injury, and previous treatments.

Patients with subacromial bursitis or rotator cuff tendinitis have a common pattern of pain and activities that elicit symptoms. Patients often complain of lateral shoulder pain, pain with overhead activities, pain with abduction and internal rotation maneuvers (e.g., turning the steering wheel), and night pain. The pain is typically improved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and steroid injections and may resolve after a course of physical therapy and activity restriction.

Patients with acromioclavicular degenerative joint disease typically have more anterior superior pain that worsens on crossing of the arm in front of the body or on reaching behind the back. Patients may describe a previous injury to the acromioclavicular joint or fall on the tip of the shoulder. Similarly, the pain is typically improved with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and steroid injections and may resolve after a course of physical therapy and activity restriction.

| • | Painful arc of motion (70 to 120 degrees) | |

| • | Tenderness at greater tuberosity | |

| • | Pain with passive abduction and internal rotation (Neer sign, Hawkins sign) | |

| • | Relief of pain with subacromial lidocaine (Xylocaine) injection (Neer test) |

Acromioclavicular Degenerative Joint Disease

| • | Painful arc of motion (120 to 180 degrees) | |

| • | Prominent acromioclavicular joint | |

| • | Tenderness at acromioclavicular joint | |

| • | Pain with cross-body adduction or maximal internal rotation |

Factors Affecting Surgical Indications and Planning

| • | Decreased range of motion (adhesive capsulitis) | |

| • | Tenderness of the acromion, motion of distal unfused acromion (os acromiale) | |

| • | Tenderness at the glenohumeral joint (degenerative changes of glenohumeral joint) | |

| • | Tenderness of long head of biceps tendon, O’Brien sign (biceps tendinitis, SLAP tear) | |

| • | Apprehension, ligamentous laxity (glenohumeral instability) | |

| • | Increased motion of distal clavicle (acromioclavicular joint instability) | |

| • | Atrophy, weakness in abduction and external rotation, liftoff test (rotator cuff tear) | |

| • | Abnormal neurologic evaluation, Hoffman sign (cervical radiculopathy) |

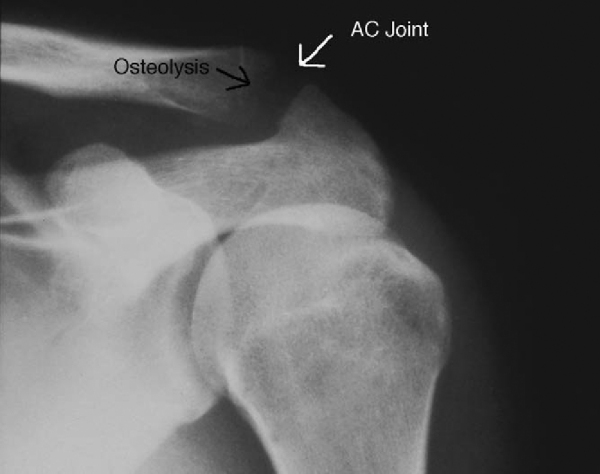

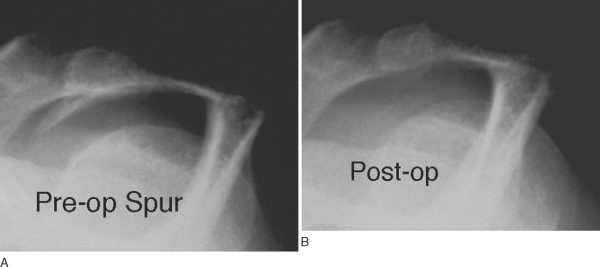

A radiographic series of the shoulder typically includes an anteroposterior radiograph of the glenohumeral joint (30 degrees from anteroposterior of shoulder) to look for glenohumeral arthritis; an outlet view for evaluation of acromial morphologic features (

Fig. 23-1

); an axillary lateral view, which is the best view to rule out an os acromiale (unfused acromion); and a Zanca view, which is the best view for evaluation of degenerative changes or osteolysis of the acromioclavicular joint (

Fig. 23-2

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-1 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-2 |

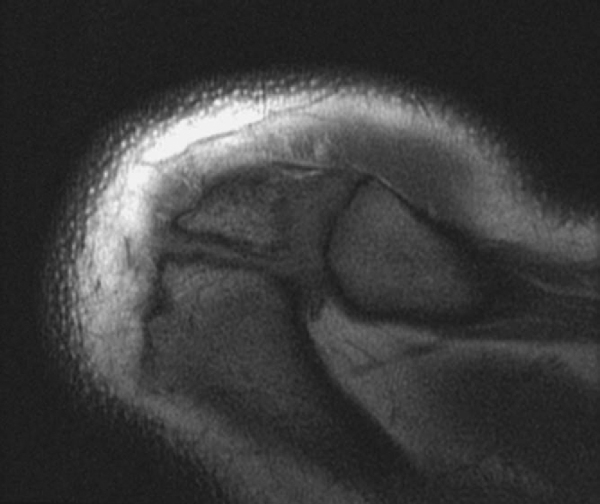

Magnetic resonance imaging may be performed to assess the condition of the rotator cuff and associated pathologic changes. It can be helpful in evaluation of an os acromiale by showing the presence of fluid and widening at the site, indicating instability of the os acromiale (

Fig. 23-3

).

Indications and Contraindications

Surgery is indicated in patients for whom 3 to 6 months of nonoperative management has failed; this includes anti-inflammatory medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injections), physical therapy (must include strengthening of the rotator cuff in nonimpingement positions), and activity modification. At the time of surgery, the patient should have full passive range of motion of the shoulder, or a manipulation under anesthesia should be considered before the arthroscopic procedure. In younger patients, ligamentous laxity and glenohumeral instability may be the primary pathologic processes, and these conditions should be addressed before a subacromial decompression is performed. If a symptomatic os acromiale is identified, it should be repaired or excised at the time of surgery. If the os is excised as part of the subacromial decompression, the distal clavicle should be preserved to maintain sufficient deltoid attachment.

If the patient has an irreparable rotator cuff tear or cuff arthropathy, disruption of the coracoacromial ligament is contraindicated. If the patient has instability of the acromioclavicular joint secondary to a grade III or higher injury, distal clavicle excision without a concomitant stabilizing procedure is contraindicated.

Associated pathologic processes, such as os acromiale, rotator cuff tear, labral tear, biceps disease, and loose bodies, should be addressed.

Indirect Versus Direct Distal Clavicle Excision

The approach to the distal clavicle should be determined preoperatively. If subacromial pathologic changes and acromioclavicular degenerative joint disease coexist, an indirect approach to the distal clavicle through the subacromial space is preferable. If the acromioclavicular joint disease is isolated, the distal clavicle may be approached directly.

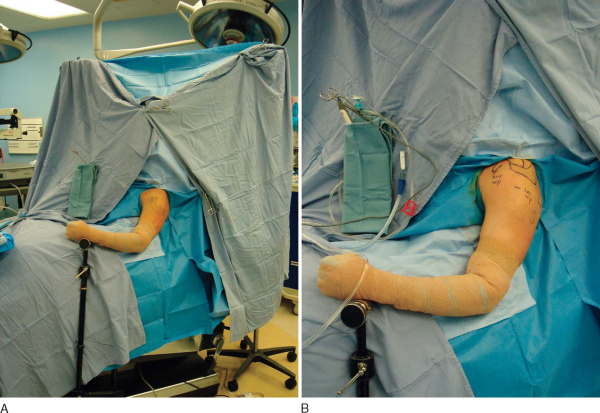

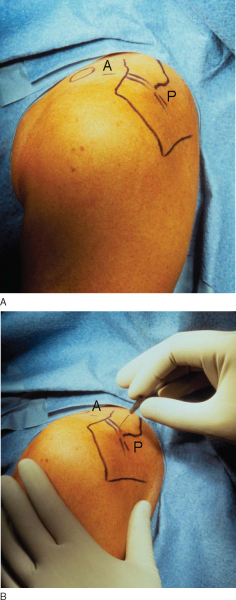

These procedures can be performed under general anesthesia, regional anesthesia, or a combination. Hypotensive anesthesia is recommended to minimize bleeding and to maximize visualization. The patient may be positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position. The senior author prefers the patient to be seated in an upright beach chair position with the acromion parallel to the floor (

Fig. 23-4

).

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

| • | Clavicle | |

| • | Acromion | |

| • | Scapular spine | |

| • | Coracoid |

Subacromial Decompression and Indirect Acromioclavicular Resection

| • | Anterior working portal | |

| • | Posterior scope portal | |

| • | Lateral working portal |

Direct Acromioclavicular Resection

| • | Anterior portal | |

| • | Posterior portal |

Subacromial Decompression and Indirect Acromioclavicular Resection

| • | Anterior portal: brachial plexus, axillary artery | |

| • | Posterior portal: axillary nerve, posterior circumflex humeral artery | |

| • | Lateral portal: axillary nerve |

Direct Acromioclavicular Resection

| • | Anterior portal: brachial plexus, axillary artery |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Examination under anesthesia evaluates range of motion and ligamentous laxity. Diagnostic arthroscopy investigates possible associated intraarticular or subacromial pathologic changes, such as os acromiale, rotator cuff tear, labral tear, biceps disease, and loose bodies.

Subacromial Decompression (

Box 23-2

)

The senior author prefers a beach chair position (see

Fig. 23-4

) and the use of an interscalene nerve block for anesthesia. The block is performed in the holding area, and the patient is brought into the operating room and transferred awake onto the already set up beach chair. The patient is secured in the upright position, and after protective goggles and extremity padding are placed, the patient is sedated. Medications are used to maintain a hypotensive state whenever it is safe for the patient. An arthroscopic fluid pump is extremely helpful in maintaining an adequate arthroscopic fluid pressure to optimize visualization in the hypervascular subacromial space. The patient’s neck should be observed by the anesthesia staff for evidence of fluid extravasation, which can lead to collapse of the softer portions of the airway and respiratory compromise. This is rarely a problem, even at very high levels of pressure, when the procedure is less than 60 minutes. In the beach chair position, gravity helps widen the subacromial space for improved viewing.

| Surgical Steps in Subacromial Decompression | ||||||||||||

|

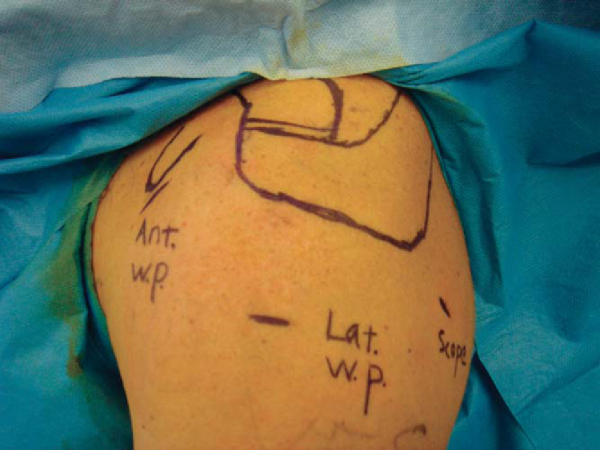

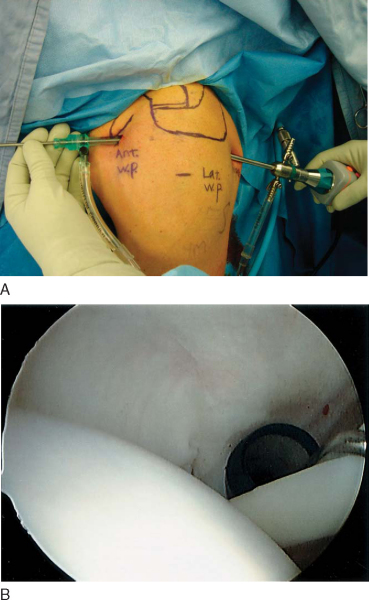

Glenohumeral arthroscopy is an important part of the subacromial decompression procedure. Because most rotator cuff tears begin on the articular side, the surgeon will miss the pathologic process unless the undersurface of the rotator cuff is evaluated from within the glenohumeral joint. The arthroscope is introduced through the posterior portal. The skin incision is made parallel to the lateral edge of the acromion and approximately 2 to 3 cm inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion. This position correlates with the softest area of the posterior shoulder, or soft spot (

Fig. 23-5

). This posterior portal position allows the surgeon to use the same posterior portal for easier visualization of the subacromial space, where most of the work is to be done. The skin and deltoid are simply translated medially to line up with the glenohumeral joint line. Before placement of the scope, it is advantageous to mark the site of the anterior portal, which is immediately lateral to the tip of the coracoid (see

Fig. 23-5

). This site will almost always be colinear with the glenohumeral joint line and serves as an aiming point when the arthroscope is introduced into the glenohumeral joint through the posterior portal. When an arthroscopic acromioclavicular resection is performed as an additional procedure, the surgeon should verify that the portal is parallel to the acromioclavicular joint. This is almost always true when the portal is placed immediately lateral to the coracoid tip.

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-5 |

The anterior portal is always lateral to the coracoid and conjoined tendon. However, it may be positioned superior or inferior, depending on the suspected pathologic process. For instance, in the presence of a full-thickness supraspinatus tendon tear, the portal can be placed between the subscapularis and superior glenohumeral ligament to prevent an additional defect immediately adjacent to the tear. In the presence of a superior labral tear, the anterior portal can be placed more lateral and above the superior glenohumeral ligament to facilitate concomitant repair of the superior labrum. Once inside the glenohumeral joint, the surgeon should systematically evaluate the cartilage, labrum, ligaments, capsule, rotator cuff, and biceps (

Fig. 23-6

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-6 |

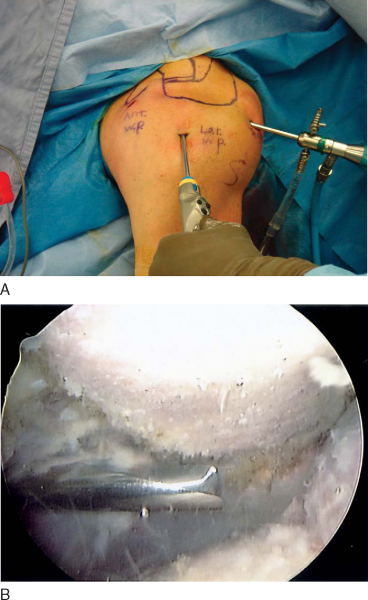

After completion of the glenohumeral arthroscopy, the joint fluid is evacuated with suction, and the arthroscope and anterior cannula are removed. The arthroscope is placed through the posterior portal into the subacromial space with an attempt to keep it immediately below the acromion to keep as much bursa as possible below the site of entry. It is helpful to use the trocar of the arthroscope to bluntly break up subacromial adhesions, moving it in a sweeping motion beneath the acromion. The anterolateral corner of the acromion is visualized before establishment of the lateral working portal. This portal is established with the help of a spinal needle to verify that the portal is parallel and slightly below the undersurface of the anterior third of the acromion, while at the same time allowing the front edge of the working instruments to be in line with the front edge of the acromion (

Fig. 23-7

). The anterior position of the portal places it closer to the area of work (i.e., the front third of the acromion), where the acromioplasty will be performed, and adjacent to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon, where most rotator cuff tears are found. It is better to err slightly lower than to be too high. A low portal can be corrected by abducting the arm, whereas a high portal makes it impossible to access the medial acromion and limits visualization of the acromioclavicular joint. The surgeon needs to make sure that the portal is no more than 3 to 4 cm from the edge of the acromion to avoid damage to the axillary nerve.

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-7 |

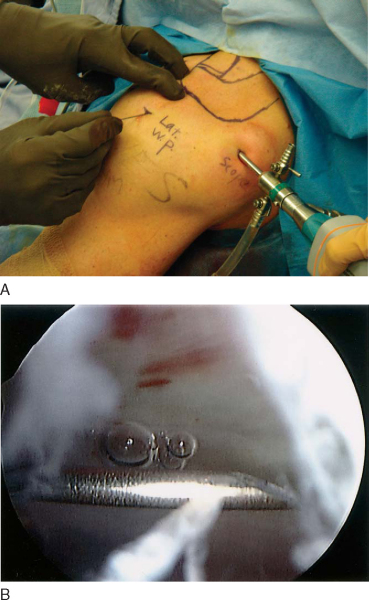

A small stab wound through skin only is used to establish the lateral portal; a semiaggressive shaver with teeth on the inner blade is used to perform a bursectomy and to expose the undersurface of the acromion (

Fig. 23-8

). It is best to start in the safer anterolateral aspect of the subacromial space, beneath the anterior third of the acromion, and to expose it first to properly identify the position of the working instruments. This will allow the surgeon to avoid doing damage to the undersurface of the deltoid. The débridement proceeds in a posterior and medial direction, until the spine of the scapula is identified. This will allow exposure of the front two thirds of the scapula, making it easier to flatten the acromion without leaving a hidden ridge at the margin of resection. The acromioclavicular joint capsule is not violated unless a combined distal clavicle excision or removal of prominent osteophytes is planned.

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-8 |

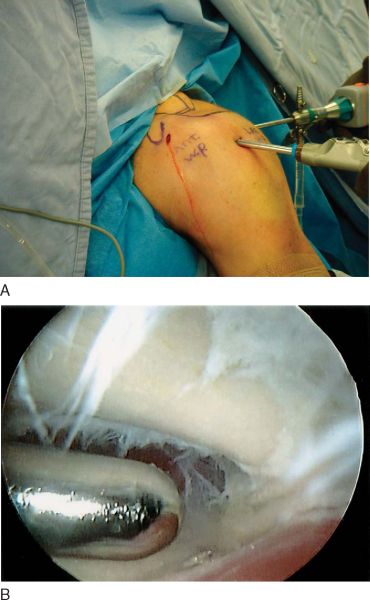

In cases in which the rotator cuff is deficient or not repairable, the coracoacromial ligament is preserved. In most other cases, the ligament is released from the front edge of the acromion with the use of an electrocautery device. This is best performed by first incising the ligament at the anterolateral corner of the acromion in a line parallel with the deltoid fibers to safely establish the depth of the muscle fibers without risk of severing the deltoid fibers perpendicular to their length. Once the depth of the muscle is known, the surgeon can safely begin to release the deltoid around the front edge of the acromion. The acromion is now exposed and ready for the acromioplasty (

Fig. 23-9

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-9 |

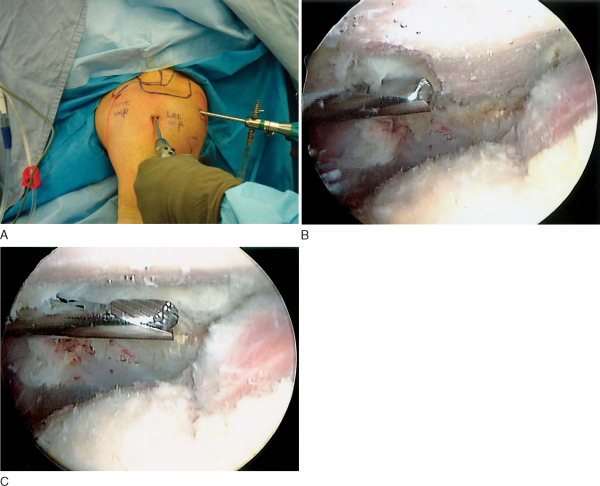

The acromioplasty is easily and efficiently performed with an oval bur placed through the lateral working portal, avoiding the extra step of switching portals (

Fig. 23-10A

). The surgeon starts at the front edge of the anterolateral aspect of the acromion, burring down and flattening the lateral half of the anterior third of the acromion until it is linear with the middle third of the acromion, which has been fully exposed (

Fig. 23-10B

). This is performed in most patients with the entire width of the bur. The lateral half is then used as a template for the medial half. The medial half is resected in the same way with another sweep of the oval bur until the entire front third of the acromion is flattened to the level of the middle third of the acromion (

Fig. 23-10C

). At completion, all bone particles are evacuated with suction, and the bursal surface of the rotator cuff is fully inspected. Postoperative radiographs will reveal removal of the acromial spur and conversion to a type I acromion (

Fig. 23-11

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-10 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-11 |

Alternatively, a “cutting block” technique can be used, in which the anterolateral spur of the acromion is burred down from the lateral working portal first. Subsequently, the arthroscope is placed into the lateral portal and the bur into the posterior portal. The acromioplasty now proceeds from posterior to anterior, with use of the just prepared posterior part of the acromion as a template for resection of the next, more anterior, part.

At completion, all bone particles are evacuated with suction, and the bursal surface of the rotator cuff is fully inspected.

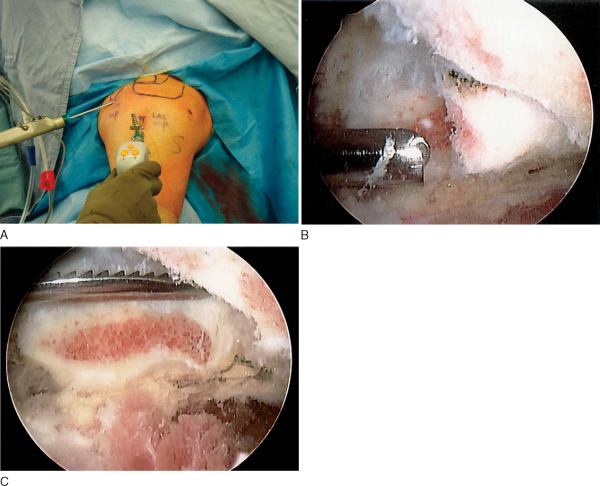

Distal Clavicle Excision, Indirect Approach (

Box 23-3

)

After completion of the subacromial decompression, the acromioclavicular joint is exposed. While the arthroscope is still in the posterior portal, an anterior working portal is established. In most people, the routine anterior glenohumeral portal placed immediately adjacent to the coracoid process will line up directly with the acromioclavicular joint. It is important to verify this preoperatively. The portal is established by placing a blunt medium trocar through the anterior portal and immediately beneath the acromioclavicular joint. With the trocar in position, the arthroscope is quickly switched from the posterior portal to the lateral working portal to provide a direct end-on view of the acromioclavicular joint and distal clavicle.

| Surgical Steps in Distal Clavicle Excision, Indirect Approach | |||||||||

|

2. Exposure of the Distal Clavicle

The trocar is removed, and an aggressive shaver is placed through the anterior portal to resect the inferior and intraarticular fibrocartilaginous disk anterior capsule of the acromioclavicular joint (

Fig. 23-12A

). The arthritic distal clavicular cartilage is exposed and scraped away with the shaver. Next, an electrocautery device is used to elevate the capsule from the edge of the clavicle. The superior posterior capsule is elevated with a hook-type electrocautery device, preserving it, as it is important for stability of the acromioclavicular joint. Exposure of the superior aspect of the distal clavicle is important to ensure that the entire width of the distal clavicle is resected without leaving any small parcels of bone that can hypertrophy and lead to residual pain in the acromioclavicular joint.

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-12 |

3. Resection of the Distal Clavicle

After exposure of the distal clavicle, a high-speed oval bur is brought in through the anterior portal and used to resect 1 cm of the distal clavicle to a smooth flat surface. Before resection, it is important to identify the orientation of the acromioclavicular joint on radiographs. This helps the surgeon identify the morphologic features of the joint, including its orientation and osteophytes. The usual orientation is a sloping surface from superolateral to inferomedial. Removal of a few millimeters of bone from the acromial facet of the acromioclavicular joint will facilitate visualization and subsequent resection.

The front half of the clavicle should be resected first (

Fig. 23-12B

). The initial resection allows the surgeon to measure the depth of resection against the intact posterior half and use it as a template for its resection. Studies have shown that between 5 and 10 mm of distal clavicle resection is necessary to successfully eliminate pain. No more than 1 cm of the distal clavicle should be removed to maintain the integrity of the superior and posterior capsule, which provides anteroposterior stability of the acromioclavicular joint, as well as that of the coracoclavicular ligaments, which provide stability against superior migration of the distal clavicle. Resection level and orientation can be verified with the use of a flat rasp with known dimensions (

Fig. 23-12C

).

Distal Clavicle Excision, Direct Approach (

Box 23-4

)

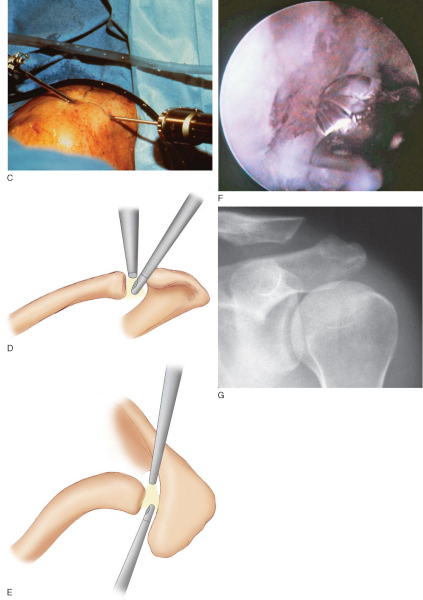

In the direct approach, the arthroscope and instruments are placed directly into the acromioclavicular joint through anterosuperior and posterosuperior portals (

Fig. 23-13A

). Because the acromioclavicular joint is variably inclined and may be extremely narrow, it is important to determine the precise joint location and inclination with a 22-gauge needle (

Fig. 23-13B

). The needle is placed in the center of the joint, and it is insufflated with arthroscopy fluid. Next, the positions of the anterior and posterior portals are verified with two additional 22-gauge needles, by verifying free outflow of fluid through the needles. The portals are aligned with the joint line, approximately 1 to 2 cm from the anterior and posterior joint edges. Instruments should enter the joint at an angle of approximately 30 degrees from the horizontal (

Fig. 23-13C

).

| Surgical Steps in Distal Clavicle Excision, Direct Approach | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 23-13 |

Once the position and angle of the acromioclavicular joint are confirmed with the needles, a No. 11 blade scalpel is used to incise the skin portals and to puncture the joint capsule. The blade is guided into the joint by sliding against the needle. The anterior aspect of the acromioclavicular joint is wider than the posterior aspect, and therefore the anterior portal is established first. A standard arthroscope is placed through a trocar with sheath into the wider anterior joint edge. The posterior portal is established under direct vision by placing a 3- to 4-mm shaver directly into the joint. Cannulas are not used as they are too restrictive and space is limited.

Under direct vision with the shaver in the posterior portal, intervening disk and synovial tissue are resected to expose the arthritic cartilage surfaces (

Fig. 23-13D and E

). The cartilage is scraped away with the shaver. A hook-tipped electrocautery device is used to elevate the joint capsule from the edge of the distal clavicle in a circumferential fashion. The capsule should be released and not excised, as it is important to the postoperative stability of the joint.

3. Resection of the Distal Clavicle

A 5- to 6-mm oval bur is placed through the posterior portal and the resection begins (

Fig. 23-13F

). The posterior one half to two thirds of the joint is resected first; 5 to 10 mm is removed from the posterior aspect. This allows precise measurement of resection by use of the known dimensions of the bur as a guide. The instruments are switched, with the arthroscope being placed into the posterior aspect of the joint. Before resecting the front portion of the distal clavicle, the surgeon verifies that the joint capsule has been sufficiently released from the front portion of the joint. Once satisfied, the surgeon places the bur through the anterior portal and removes the front portion of the clavicle. The posterior resection is used as a template, and the clavicle is resected to a smooth flat surface. Bone debris is removed by suction, and the distal clavicle is inspected to make certain that there are no retained particles of bone adherent to the joint capsule. Postoperative radiographs demonstrate smooth resection of the distal clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint (

Fig. 23-13G

).

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | ||||||||||||

|

Patients are seen after 7 to 10 days for suture removal and wound inspection.

Patients wear a sling and compressive cold device for comfort during the first 48 hours. Pendulum exercises are started immediately, and a formal rehabilitation program begins within the first 24 to 48 hours. This program includes passive and active range-of-motion exercises in all planes of motion. Strengthening exercises are initiated within the first few weeks after surgery, when the patients have regained close to full range of motion and their comfort level will tolerate the stress. Return to most activities is expected within 6 weeks, and full return to strenuous activities is expected by 3 to 6 months.

| • | Incomplete resection of acromion or distal clavicle | |

| • | Regrowth of acromion or distal clavicle | |

| • | Infection | |

| • | Adhesive capsulitis | |

| • | Neurovascular injury |

After arthroscopic acromioplasty and subacromial decompression, good to excellent results are achieved in nearly 80% of patients, demonstrated by decreased pain with activities and improved function. However, less than 70% of throwing athletes return to their sport postoperatively (

Table 23-1

). In patients with both subacromial impingement syndrome and painful acromioclavicular degenerative joint disease, concomitant subacromial decompression and distal clavicle excision produce good to excellent results in nearly 90% of patients. However, patients who have an extended duration of symptoms before surgery or damage to the rotator cuff tendons have poorer outcomes (

Table 23-2

). For isolated acromioclavicular joint disease without acromioclavicular hypermobility, direct distal clavicle excision through a superior approach yields good to excellent results in more than 90% of patients (

Table 23-3

).

| Author | Followup | No. of Patients | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ellman[5] (1987) | 17 months (12-36 months) | 49 | 88% good–excellent |

| Esch et al[6] (1988) | 19 months (12-36 months) | 71 | 77% good–excellent |

| Gartsman[8] (1990) | 29 months (24-48 months) | 126 | 87% no rotator cuff tear 83% partial-thickness rotator cuff |

| tear | |||

| Roye et al[14] (1995) | 41 months (2-7 years) | 88 | 89% nonthrowing athletes |

| 68% throwing athletes | |||

| Stephens et al[15] (1998) | 8 years 5 months (6-10 years) | 82 | 81% good–excellent |

| 67% throwing athletes |

| Author | Followup | No. of Patients | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kay et al[9] (2003) | 6 years (3.9-9 years) | 20 | 100% good–excellent |

| 25% re-formed distal clavicle | |||

| Lozman et al[11] (1995) | 32 months (minimum 2 years) | 18 | 89% good–excellent |

| Levine et al[10] (1998) | 32.5 months (24-70 months) | 24 | 88% good–excellent |

| Martin et al[12] (2001) | 4 years 10 months (3-8 years) | 31 | 100% good–excellent |

| Author | Followup | No. of Patients | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auge and Fischer[1] (1998) | 18.7 months (12-25 months) | 10 | 100% good–excellent |

| 100% osteolysis | |||

| Flatow et al[7] (1995) | 31 months (24-49 months) | 41 | 93% osteoarthritis or osteolysis |

| 58% acromioclavicular hypermobility |

1.

Auge W, Fischer R: Arthroscopic distal clavicle resection for isolated atraumatic osteolysis in weight lifters.

Am J Sports Med 1998; 26:189-192.

2.

Bigliani L, Levine W: Subacromial impingement syndrome.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997; 79:1854-1868.

3.

Blazar P, Iannotti J, Williams G: Anteroposterior instability of the distal clavicle after distal clavicle resection.

Clin Orthop 1998; 348:114-120.

4.

Debski R, Fenwick J, Vangura A, et al: Effect of arthroscopic procedures on the acromioclavicular joint.

Clin Orthop 2003; 406:89-96.

5.

Ellman H: Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: analysis of one- to three-year results.

Arthroscopy 1987; 3:173-181.

6.

Esch J, Ozerkis L, Helgager J, et al: Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: results according to the degree of rotator cuff tear.

Arthroscopy 1988; 4:241-249.

7.

Flatow E, Duralde X, Nicholson G, et al: Arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle with a superior approach.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4:41-50.

8.

Gartsman G: Arthroscopic acromioplasty for lesions of the rotator cuff.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72:169-180.

9.

Kay S, Dragoo J, Lee R: Long-term results of arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle with concomitant subacromial decompression.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:805-809.

10.

Levine W, Barron O, Yamaguchi K, et al: Arthroscopic distal clavicle resection from a bursal approach.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:52-61.

11.

Lozman P, Hechtman K, Uribe J: Combined arthroscopic management of impingement syndrome and acromioclavicular arthritis.

J South Orthop Assoc 1995; 4:177-181.

12.

Martin S, Baumgarten T, Andrews J: Arthroscopic resection of the distal aspect of the clavicle with concomitant subacromial decompression.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83:328-335.

13.

McFarland E, Selhi H, Keyurapan E: Clinical evaluation of impingement: what to do and what works.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88:432-441.

14.

Roye R, Grana W, Yates C: Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: two to seven-year followup.

Arthroscopy 1995; 11:301-306.

15.

Stephens S, Warren R, Payne L, et al: Arthroscopic acromioplasty: a 6- to 10-year followup.

Arthroscopy 1998; 14:382-388.