Pelvis

Authors: Koval, Kenneth J.; Zuckerman, Joseph D.

Title: Handbook of Fractures, 3rd Edition

Copyright ©2006 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > IV – Lower Extremity Fractures and Dislocations > 25 – Pelvis

25

Pelvis

ANATOMY

-

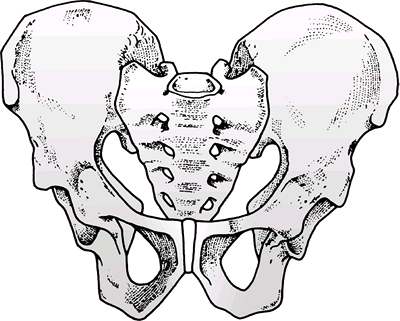

The pelvic ring

is composed of the sacrum and two innominate bones joined anteriorly at

the symphysis and posteriorly at the paired sacroiliac joints (Figs. 25.1 and 25.2). -

The innominate

bone is formed at maturity by the fusion of three ossification centers:

the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis through the triradiate cartilage

at the dome of the acetabulum. -

The pelvic brim

is formed by the arcuate lines that join the sacral promontory

posteriorly and the superior pubis anteriorly. Below this is the true or lesser pelvis, in which are contained the pelvic viscera. Above this is the false or greater pelvis that represents the inferior aspect of the abdominal cavity. -

Inherent stability of the pelvis is

conferred by ligamentous structures. These may be divided into two

groups according to the ligamentous attachments:-

Sacrum to ilium: The strongest and most

important ligamentous structures occur in the posterior aspect of the

pelvis connecting the sacrum to the innominate bones.-

The sacroiliac ligamentous complex is divided into posterior (short and long) and anterior ligaments. Posterior ligaments provide most of the stability.

-

The sacrotuberous ligament

runs from the posterolateral aspect of the sacrum and the dorsal aspect

of the posterior iliac spine to the ischial tuberosity. This ligament,

in association with the posterior sacroiliac ligaments, is especially

important in helping maintain vertical stability of the pelvis. -

The sacrospinous ligament

is triangular, running from the lateral margins of the sacrum and

coccyx and inserting on the ischial spine. It is more important in

maintaining rotational control of the pelvis if the posterior

sacroiliac ligaments are intact.

-

-

Pubis to pubis: This is the symphysis pubis.

-

-

Additional stability is conferred by ligamentous attachments between the lumbar spine and the pelvic ring:

-

The iliolumbar ligaments originate from the L4 and L5 transverse processes and insert on the posterior iliac crest.

-

The lumbosacral ligaments originate from the transverse process of L5 to the ala of the sacrum.

-

-

The transversely placed ligaments resist

rotational forces and include the short posterior sacroiliac, anterior

sacroiliac, iliolumbar, and sacrospinous ligaments. -

The vertically placed ligaments resist

vertical shear (VS) and include the long posterior sacroiliac,

sacrotuberous, and lateral lumbosacral ligaments.

P.276

PELVIC STABILITY

|

|

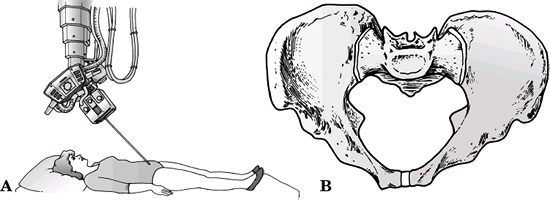

Figure 25.1. Lateral projection of the left innominate bone. Note the muscular attachments to the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

|

-

A stable injury is defined as one that can withstand normal physiologic forces without abnormal deformation.

-

Penetrating trauma infrequently results in pelvic ring destabilization.

-

An unstable injury may be characterized by the type of displacement as:

-

Rotationally unstable (open and externally rotated, or compressed and internally rotated).

-

Vertically unstable.

-

McBroom and Tile

Sectioned ligaments of the pelvis determine relative

contributions to pelvic stability (these included bony equivalents to

ligamentous disruptions):

contributions to pelvic stability (these included bony equivalents to

ligamentous disruptions):

-

Symphysis: pubic diastasis <2.5 cm

-

Symphysis and sacrospinous ligaments:

>2.5 cm of pubic diastasis (note that these are rotational movements

and not vertical or posterior displacements) -

Symphysis, sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and posterior sacroiliac: unstable vertically, posteriorly, and rotationally

P.277

MECHANISM OF INJURY

|

|

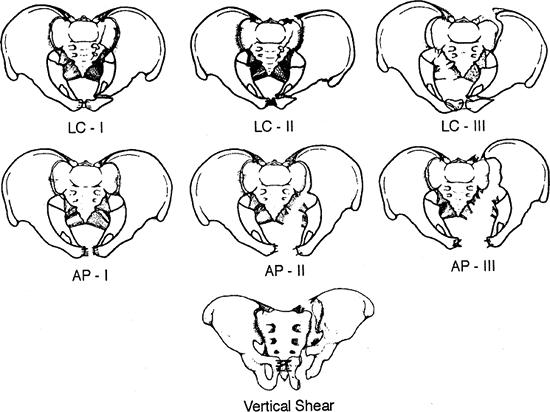

Figure 25.2. Medial projection of the left innominate bone with muscle attachments and outline of the sacroiliac joint surface.

(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

|

-

These may be divided into low-energy

injuries, which typically result in fractures of individual bones, or

high-energy fractures, which may result in pelvic ring disruption.-

Low-energy injuries may result from

sudden muscular contractions in young athletes that cause an avulsion

injury, a low-energy fall, or a straddle-type injury. -

High-energy injuries typically result

from a motor vehicle accident, pedestrian-struck mechanism, motorcycle

accident, fall from heights, or crush mechanism.

-

-

Impact injuries result when a moving

victim strikes a stationary object or vice versa. Direction, magnitude,

and nature of the force all contribute to the type of fracture. -

Crush injuries occur when a victim is

trapped between the injurious force, such as motor vehicle, and an

unyielding environment, such as the ground or pavement. In addition to

those factors mentioned previously, the position of the victim, the

duration of the crush, and whether the force was direct or a “rollover”

(resulting in a changing force vector) are important to understanding

the fracture pattern. -

Specific injury patterns vary by the direction of force application:

-

Anteroposterior (AP) force

-

This results in external rotation of the hemipelvis.

-

The pelvis springs open, hinging on the intact posterior ligaments.

-

-

Lateral compression (LC) force: This is

most common and results in impaction of cancellous bone through the

sacroiliac joint and sacrum. The injury pattern depends on location of

force application:-

Posterior half of the ilium: This is classic LC with minimal soft tissue disruption. This is often a stable configuration.

-

Anterior half of the iliac wing: This

rotates the hemipelvis inward. It may disrupt the posterior sacroiliac

ligamentous complex. If this force continues to push the hemipelvis

across to the contralateral side, it will push the contralateral

hemipelvis out into external rotation, producing LC on the ipsilateral

side and an external rotation injury on the contralateral side. -

Greater trochanteric region: This may be associated with a transverse acetabular fracture.

-

External rotation abduction force: This is common in motorcycle accidents.

-

Force application occurs through the femoral shafts and head when the leg is externally rotated and abducted.

-

This tends to tear the hemipelvis from the sacrum.

-

-

Shear force

-

This leads to a completely unstable

fracture with triplanar instability secondary to disruption of the

sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and sacroiliac ligaments. -

In the elderly individual, bone strength will be less than ligamentous strength and will fail first.

-

In a young individual, bone strength is greater, and thus ligamentous disruptions usually occur.

-

-

P.278

CLINICAL EVALUATION

-

Perform patient primary assessment

(ABCDE): airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure. This

should include a full trauma evaluation. -

Initiate resuscitation: Address life-threatening injuries.

-

Evaluate injuries to head, chest, abdomen, and spine.

-

Identify all injuries to extremities and pelvis, with careful assessment of distal neurovascular status.

-

Pelvic instability may result in a

leg-length discrepancy involving shortening on the involved side or a

markedly internally or externally rotated lower extremity. -

The AP-LC test for pelvic instability should be performed once only and involves rotating the pelvis internally and externally.

-

“The first clot is the best clot.” Once

disrupted, subsequent thrombus formation of a retroperitoneal

hemorrhage is difficult because of hemodilution by administered

intravenous fluid and exhaustion of the body’s coagulation factors by

the original thrombus.

-

-

Massive flank or buttock contusions and swelling with hemorrhage are indicative of significant bleeding.

-

Palpation of the posterior aspect of the

pelvis may reveal a large hematoma, a defect representing the fracture,

or a dislocation of the sacroiliac joint. Palpation of the symphysis

may also reveal a defect. -

The perineum must be carefully inspected for the presence of a lesion representing an open fracture.

P.279

HEMODYNAMIC STATUS

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage may be associated with

massive intravascular volume loss. The usual cause of retroperitoneal

hemorrhage secondary to pelvic fracture is a disruption of the venous

plexus in the posterior pelvis. It may also be caused by a large-vessel

injury, such as external or internal iliac disruption. Large-vessel

injury causes rapid, massive hemorrhage with frequent loss of the

distal pulse and marked hemodynamic instability. This often

necessitates immediate surgical exploration to gain proximal control of

the vessel before repair. The superior gluteal artery is occasionally

injured and can be managed with rapid fluid resuscitation, appropriate

stabilization of the pelvic ring, and embolization.

massive intravascular volume loss. The usual cause of retroperitoneal

hemorrhage secondary to pelvic fracture is a disruption of the venous

plexus in the posterior pelvis. It may also be caused by a large-vessel

injury, such as external or internal iliac disruption. Large-vessel

injury causes rapid, massive hemorrhage with frequent loss of the

distal pulse and marked hemodynamic instability. This often

necessitates immediate surgical exploration to gain proximal control of

the vessel before repair. The superior gluteal artery is occasionally

injured and can be managed with rapid fluid resuscitation, appropriate

stabilization of the pelvic ring, and embolization.

-

Options for immediate hemorrhage control include:

-

Application of military antishock trousers (MAST). This is typically performed in the field.

-

Application of an anterior external fixator.

-

Wrapping of a pelvic binder circumferentially around the pelvis (or sheet if a binder is not available).

-

Application of a pelvic C-clamp.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation

(ORIF): This may be undertaken if the patient is undergoing emergency

laparotomy for other indications; it is frequently contraindicated by

itself because loss of the tamponade effect may encourage further

hemorrhage. -

Consider angiography or embolization if hemorrhage continues despite closing of the pelvic volume.

-

NEUROLOGIC INJURY

-

Lumbosacral plexus and nerve root injuries may be present, but they may not be apparent in an unconscious patient.

GENITOURINARY AND GASTROINTESTINAL INJURY

-

Bladder injury: 20% incidence occurs with pelvic trauma.

-

Urethral injury: 10% incidence occurs with pelvic fractures, in male patients much more frequently than in female patients.

-

Examine for blood at the urethral meatus or blood on catheterization.

-

Examine for a high-riding or “floating” prostate on rectal examination.

-

Clinical suspicion should be followed by a retrograde urethrogram.

-

Bowel Injury

Perforations in the rectum or anus owing to osseous fragments are technically open injuries and should be treated as such.

P.280

Infrequently, entrapment of bowel in the fracture site with

gastrointestinal obstruction may occur. If either is present, the

patient should undergo diverting colostomy.

|

|

Figure 25.3. Anteroposterior view of the pelvis.

(From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

|

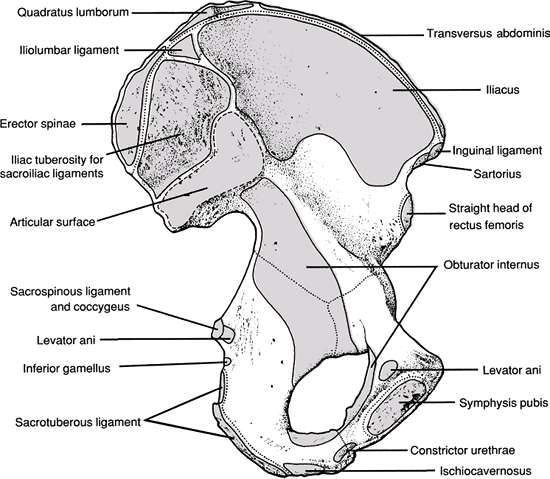

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Standard trauma radiographs include an AP view of the chest, a lateral view of the cervical spine, and an AP view of the pelvis.

-

AP of the pelvis (Fig. 25.3):

-

Anterior lesions: pubic rami fractures and symphysis displacement

-

Sacroiliac joint and sacral fractures

-

Iliac fractures

-

L5 transverse process fractures

-

-

Special views of the pelvis include:

-

Obturator and iliac oblique views: They may be utilized in suspected acetabular fractures (see Chapter 26).

-

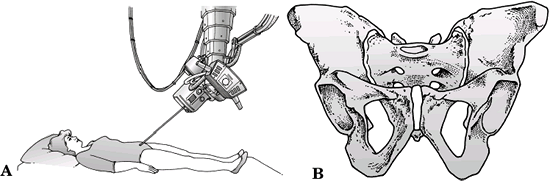

Inlet radiograph (Fig. 25.4): This is taken with the patient supine with the tube directed 60 degrees caudally, perpendicular to the pelvic brim.

-

This is useful for determining anterior or posterior displacement of the sacroiliac joint, sacrum, or iliac wing.

-

It may determine internal rotation deformities of the ilium and sacral impaction injuries.

-

-

Outlet radiograph (Fig. 25.5): This is taken with the patient supine with the tube directed 45 degrees cephalad.

-

This is useful for determination of vertical displacement of the hemipelvis.

-

It may allow for visualization of subtle

signs of pelvic disruption, such as a slightly widened sacroiliac

joint, discontinuity of the sacral borders, nondisplaced sacral

fractures, or disruption of the sacral foramina.![]() Figure 25.4. Inlet view of the pelvis: technique (A) and artist’s sketch (B).(Modified from Tile M. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.)

Figure 25.4. Inlet view of the pelvis: technique (A) and artist’s sketch (B).(Modified from Tile M. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.)

P.281 -

-

-

Computed tomography: This is excellent for assessing the posterior pelvis, including the sacrum and sacroiliac joints.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging: It has

limited clinical utility owing to restricted access to a critically

injured patient, prolonged duration of imaging, and equipment

constraints. However, it may provide superior imaging of genitourinary

and pelvic vascular structures. -

Stress views: Push-pull radiographs are performed while the patient is under general anesthesia to assess vertical stability.

-

Tile defined instability as ≥0.5 cm of motion.

-

Bucholz, Kellam, and Browner consider ≥1 cm of vertical displacement unstable.

-

-

Radiographic signs of instability include:

-

Sacroiliac displacement of 5 mm in any plane.

-

Posterior fracture gap (rather than impaction).

-

Avulsion of the fifth lumbar transverse

process, the lateral border of the sacrum (sacrotuberous ligament), or

the ischial spine (sacrospinous ligament). Figure 25.5. Outlet view of the pelvis: technique (A) and artist’s sketch (B).(Modified from Tile M. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.)

Figure 25.5. Outlet view of the pelvis: technique (A) and artist’s sketch (B).(Modified from Tile M. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.)

-

P.282

|

Table 25.1. Injury classification keys according to the Young and Burgess system

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

CLASSIFICATION

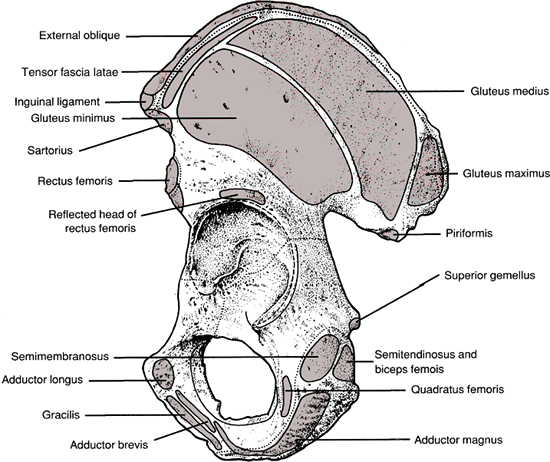

Young and Burgess (Table 25.1 and Fig. 25.6)

This system is based on the mechanism of injury.

-

LC: This is an implosion of the pelvis

secondary to laterally applied force that shortens the anterior

sacroiliac, sacrospinous, and sacrotuberous ligaments. One may see

oblique fractures of the pubic rami, ipsilateral or contralateral to

the posterior injury.Type I: Sacral impaction on the side of impact. Transverse fractures of the pubic rami are stable. Type II: Posterior iliac wing fracture

(crescent) on the side of impact with variable disruption of the

posterior ligamentous structures resulting in variable mobility of the

anterior fragment to internal rotation stress. It maintains vertical

stability and may be associated with an anterior sacral crush injury.Type III: LC-I or LC-II injury on the

side of impact; force continued to contralateral hemipelvis to produce

an external rotation injury (“windswept pelvis”) owing to sacroiliac,

sacrotuberous, and sacrospinous ligamentous disruption. Instability may

result with hemorrhage and neurologic injury secondary to traction

injury on the side of sacroiliac injury. -

AP compression (APC): This is anteriorly

applied force from direct impact or indirectly transferred via the

lower extremities or ischial tuberosities resulting in external

rotation injuries, symphyseal diastasis, or longitudinal rami fractures.![]() Figure 25.6. Young and Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures.(From Young JWR, Burgess AR. Radiologic Management of Pelvic Ring Fractures. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1987, with permission.)

Figure 25.6. Young and Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures.(From Young JWR, Burgess AR. Radiologic Management of Pelvic Ring Fractures. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1987, with permission.)Type I: Less than 2.5 cm of symphyseal diastasis. Vertical fractures of one or both pubic rami occur, with intact posterior ligaments. Type II: More than 2.5 cm of symphyseal

diastasis; widening of sacroiliac joints; caused by anterior sacroiliac

ligament disruption. Disruption of the sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and

symphyseal ligaments with intact posterior sacroiliac ligaments results

in an “open book” injury with internal and external rotational

instability; vertical stability is maintained.Type III: Complete disruption of the

symphysis, sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and sacroiliac ligaments

resulting in extreme rotational instability and lateral displacement;

no cephaloposterior displacement. It is completely unstable with the

highest rate of associated vascular injuries and blood loss. -

VS: vertically or longitudinally applied

forces caused by falls onto an extended lower extremity, impacts from

above, or motor vehicle accidents with an extended lower extremity

against the floorboard or dashboard. These injuries are typically

associated with complete disruption of the symphysis, sacrotuberous,

sacrospinous, and sacroiliac ligaments and result in extreme

instability, most commonly in a cephaloposterior direction because of

the inclination of the pelvis. They have a highly associated incidence

of neurovascular injury and hemorrhage. -

Combined mechanical (CM): combination of injuries often resulting from crush mechanisms. The most common are VS and LC.

P.283

P.284

Tile Classification

| Type A | Stable |

| A1: | Fractures of the pelvis not involving the ring; avulsion injuries |

| A2: | Stable, minimal displacement of the ring |

| Type B: | Rotationally unstable, vertically stable |

| B1: | External rotation instability; open-book injury |

| B2: | LC injury; internal rotation instability; ipsilateral only |

| B3: | LC injury; bilateral rotational instability (bucket handle) |

| Type C: | Rotationally, and vertically unstable |

| C1: | Unilateral injury |

| C2: | Bilateral injury, one side rotationally unstable, with the contralateral side vertically unstable |

| C3: | Bilateral injury, both sides rotationally and vertically unstable with an associated acetabular fracture |

OTA Classification of Pelvic Fractures

See Fracture and Dislocation Compendium at http://www.ota.org/compendium/index.htm.

FACTORS INCREASING MORTALITY

-

Type of pelvic ring injury

-

Posterior disruption is associated with higher mortality (APC III, VS, LC III)

-

-

High Injury Severity Score (Tile, 1980, McMurty, 1980)

-

Associated injuries

-

Head and abdominal, 50% mortality

-

-

Hemorrhagic shock on admission (Gilliland, 1982)

-

Requirement for large quantities of blood

-

24 U versus 7 U (McMurty, 1980)

-

-

Perineal lacerations, open fractures (Hanson, 1991)

-

Increased age (Looser, 1976)

P.285

Morel-Lavallé Lesion (Skin Degloving Injury)

-

Infected in one-third of cases

-

Requires thorough debridement before definitive surgery

TREATMENT

-

The recommended management of pelvic

fractures varies from institution to institution, a finding

highlighting that these are difficult injuries to treat.

Nonoperative

Fractures amenable to nonoperative treatment include:

-

Lateral impaction type injuries with minimal (<1.5 cm) displacement.

-

Pubic rami fractures with no posterior displacement.

-

Gapping of pubic symphysis <2.5 cm.

-

Rehabilitation:

-

Protect weight bearing typically with a walker or crutches initially.

-

Serial radiographs are required after mobilization has begun to monitor for subsequent displacement.

-

If displacement of the posterior ring

>1 cm is noted, weight bearing should be stopped. Operative

treatment should be considered for gross displacement.

-

Tile: Stabilization Options

-

Stable (A1, A2): Stable, minimally

displaced fractures with minimal disruption of the bony and ligamentous

stability of the pelvic ring may successfully be treated with protected

weight bearing and symptomatic treatment. -

Open-book (B1)

-

Symphyseal diastasis <2 cm: Protected weightbearing and symptomatic treatment are indicated.

-

Symphyseal diastasis >2 cm: External

fixation or symphyseal plate is performed (ORIF preferred if laparotomy

for associated injuries and no open injury), with possible fixation for

the posterior injury.

-

-

LC (B2, B3)

-

Ipsilateral only: Elastic recoil may improve pelvic anatomy. No stabilization is necessary.

-

Contralateral (bucket-handle): The posterior sacral complex is commonly compressed.

-

Leg-length discrepancy <1.5 cm: No stabilization is necessary.

-

Leg-length discrepancy >1.5 cm: The choice is external fixation versus ORIF.

-

-

-

Rotationally and vertically unstable (C1, C2, C3): External fixation with or without skeletal traction and ORIF are options.

P.286

Operative Techniques

-

External fixation: This can be applied as

a construct mounted on two to three 5-mm pins spaced 1 cm apart along

the anterior iliac crest, or with the use of single pins placed in the

supraacetabular area in an AP direction (Hanover frame).-

External fixation is a resuscitative

fixation and can only be used for definitive fixation of anterior

pelvis injuries; it cannot be used as definitive fixation of

posteriorly unstable injuries.

-

-

Internal fixation: This significantly increases the forces resisted by the pelvic ring compared with external fixation.

-

Iliac wing fractures: Open reduction and stable internal fixation are performed using lag screws and neutralization plates.

-

Diastasis of the pubic symphysis: Plate fixation is used if no open injury or cystostomy tube is present.

-

Sacral fractures: Transiliac bar fixation

may be inadequate or may cause compressive neurologic injury; in these

cases, plate fixation or sacroiliac screw fixation may be indicated. -

Unilateral sacroiliac dislocation: Direct fixation with cancellous screws or anterior sacroiliac plate fixation is used.

-

Bilateral posterior unstable disruptions:

Fixation of the displaced portion of the pelvis to the sacral body may

be accomplished by posterior screw fixation.

-

Special Considerations

-

Open fractures: In addition to fracture

stabilization, hemorrhage control, and resuscitation, priority must be

given to evaluation of the anus, rectum, vagina, and genitourinary

system.-

Anterior and lateral wounds generally are protected by muscle and are not contaminated by internal sources.

-

Posterior and perineal wounds may be contaminated by rectal and vaginal tears and genitourinary injuries.

-

Colostomy may be necessary for large bowel perforations or injuries to the anorectal region.

-

Colostomy is indicated for any open injury where the fecal stream will contact the open area.

-

-

Urologic injury

-

The incidence is 15%.

-

Blood at the meatus or a high-riding prostate may be noted.

-

Eventual swelling of the scrotum and labia (occasional bleeding artery requiring surgery) may occur.

-

Retrograde urethrogram is indicated in

patients with suspicion of urologic injury, but one should ensure

hemodynamic stability as embolization may be difficult because of dye

extravasation. -

Intra peritoneal bladder ruptures are repaired. Extra peritoneal ruptures may be observed.

-

Urethral injuries are repaired on a delayed basis.

-

-

Neurologic injury

-

L2 to S4 are possible.

-

L5 and S1 are most common.

-

Neurologic injury depends on the location of the fracture and the amount of displacement.

-

Sacral fractures: neurologic injury

-

Decompression of sacral foramen may be indicated if progressive loss of neural function occurs.

-

It may take up to 3 years for recovery.

-

-

Hypovolemic shock: origin

-

Intrathoracic bleeding

-

Intraperitoneal bleeding

-

Diagnostic tables

-

Ultrasound

-

Peritoneal tap

-

Computed tomography

-

-

Retroperitoneal bleeding

-

Blood loss from open wounds

-

Bleeding from multiple extremity fractures

-

-

Average blood replacement (Burgess, J Trauma 1990)

-

LC = 3.6 U

-

AP = 14.8 U

-

VS = 9.2 U

-

CM = 8.5 U

-

-

Mortality (Burgess, J Trauma 1990)

-

Hemodynamically stable patients 3%

-

Unstable patients 38%

-

LC: head injury major cause of death

-

APC: pelvic and visceral injury major cause of death

-

LC1 and LC2 → 50% brain injury

-

LC3 (windswept pelvis: rollover/crush)

-

60% retroperitoneal hematoma

-

20% bowel injury

-

-

AP3 (comprehensive posterior instability)

-

67% shock

-

59% sepsis

-

37% death

-

18.5% adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

-

-

VS

-

63% shock

-

56% brain injury

-

25% splenic injury

-

25% death

-

23% lung injury

-

-

-

Postoperative management: In general, early mobilization is desired.

-

Aggressive pulmonary toilet should be

pursued with incentive spirometry, early mobilization, encouraged deep

inspirations and coughing, and suctioning or chest physical therapy if

necessary. -

Prophylaxis against thromboembolic

phenomena should be undertaken, with a combination of elastic

stockings, sequential compression devices, and chemoprophylaxis if

hemodynamic status allows. Duplex ultrasound examinations may be

necessary. Thrombus formation may necessitate anticoagulation and/or

vena caval filter placement. -

Weight-bearing status may be advanced as follows:

-

Full weight bearing on the uninvolved lower extremity occurs within several days.

-

Partial weight bearing on the involved lower extremity is recommended for at least 6 weeks.

-

Full weight bearing on the affected extremity without crutches is indicated by 12 weeks.

-

Patients with bilateral unstable pelvic

fractures should be mobilized from bed to chair with aggressive

pulmonary toilet until radiographic evidence of fracture healing is

noted. Partial weight bearing on the less injured side is generally

tolerated by 12 weeks.

-

P.288 -

COMPLICATIONS

-

Infection: The incidence is variable,

ranging from 0% to 25%, although the presence of wound infection does

not preclude a successful result. The presence of contusion or shear

injuries to soft tissues is a risk factor for infection if a posterior

approach is used. This risk is minimized by a percutaneous posterior

ring fixation. -

Thromboembolism: Disruption of the pelvic

venous vasculature and immobilization constitute major risk factors for

the development of deep venous thromboses. -

Malunion: Significant disability may

result, with complications including chronic pain, limb length

inequalities, gait disturbances, sitting difficulties, low back pain,

and pelvic outlet obstruction. -

Nonunion: This is rare, although it tends

to occur more in younger patients (average age 35 years) with possible

sequelae of pain, gait abnormalities, and nerve root compression or

irritation. Stable fixation and bone grafting are usually necessary for

union.