Forearm

Editors: Morrey, Bernard F.; Morrey, Matthew C.

Title: Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery: Relevant Surgical Exposures, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section I – Upper Extremity > 2 – Forearm

2

Forearm

Bernard F. Morrey

Clinically, there are only three relevant exposures of the forearm. These expose the radius from a posterior (Thompson) and from an anterior (Henry) perspective and the ulna from a dorsal perspective. All three are readily extended depending on the pathology being treated.

POSTERIOR APPROACH TO THE RADIUS (THOMPSON)

Indications

Fracture, tumor, and infection when access to posterior radius desired.

Note

This approach is not commonly employed but may be used

to expose either the proximal, mid or distal radius but is most

effective for the proximal and middle thirds.

to expose either the proximal, mid or distal radius but is most

effective for the proximal and middle thirds.

Position

The patient is supine with arm across the chest or on arm/elbow table.

Landmarks

Lateral epicondyle to radial styloid.

Technique

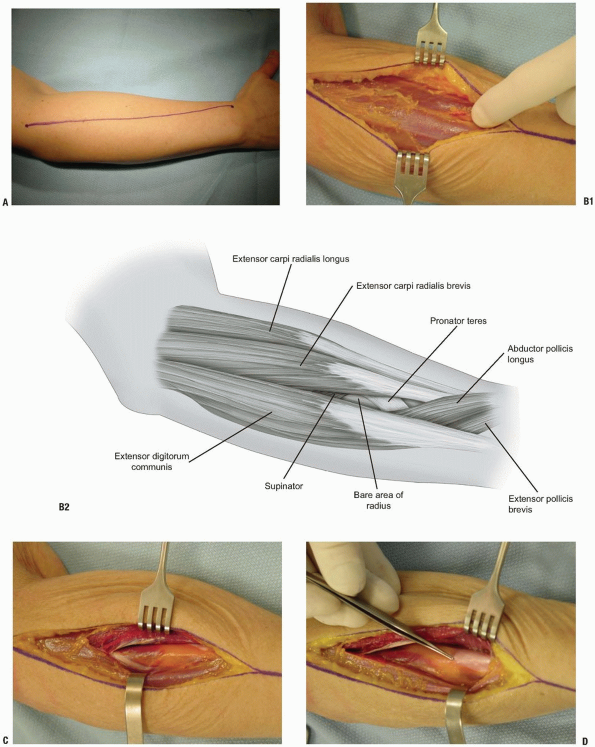

1. Incision: straight from the lateral epicondyle to the

radial styloid. With the forearm pronated the line of the incision is a

straight line. Use all or any portion (Fig. 2-1A).

radial styloid. With the forearm pronated the line of the incision is a

straight line. Use all or any portion (Fig. 2-1A).

2. Expose the interval between the anterior border of

the extensor digitorum communis and the posterior or radial border of

the extensor carpi radialis brevis.

the extensor digitorum communis and the posterior or radial border of

the extensor carpi radialis brevis.

3. Distally palpate the bare portion of the radius

distally that superficially demarcates the natural interval between

these two muscle groups (Fig. 2-1B).

Deep to these muscles the bare area identifies the distal aspect of the

supinator and proximal attachment of the pronator teres tendon.

distally that superficially demarcates the natural interval between

these two muscle groups (Fig. 2-1B).

Deep to these muscles the bare area identifies the distal aspect of the

supinator and proximal attachment of the pronator teres tendon.

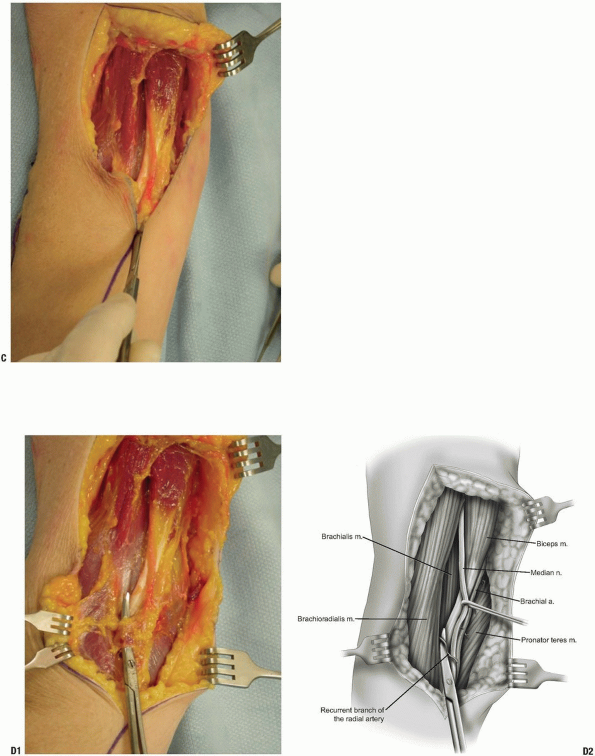

4. The forearm fascia is split proximally and distally

allowing the extensor digitorum communis to be retracted posteriorly

and extensor carpi radialis brevis to be retracted anteriorly to the

ulnar side of the radius (Fig. 2-1C). The bare shaft of the radius between the supinator and pronator attachments is well defined (Fig. 2-1D).

allowing the extensor digitorum communis to be retracted posteriorly

and extensor carpi radialis brevis to be retracted anteriorly to the

ulnar side of the radius (Fig. 2-1C). The bare shaft of the radius between the supinator and pronator attachments is well defined (Fig. 2-1D).

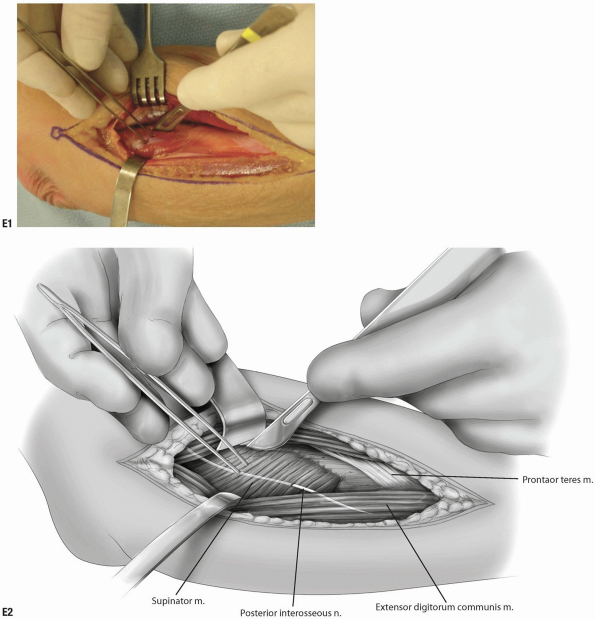

5. Proximally with the forearm in supination, the

supinator muscle is noted and the posterior interosseous nerve observed

and may or may not be exposed.

supinator muscle is noted and the posterior interosseous nerve observed

and may or may not be exposed.

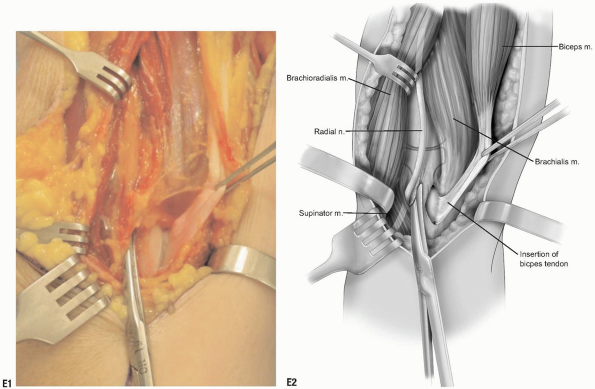

6. The supinator muscle is then released either in its

mid-portion exposing the posterior interosseous nerve or, more

commonly, is released from the shaft of the radius (Fig. 2-1E).

mid-portion exposing the posterior interosseous nerve or, more

commonly, is released from the shaft of the radius (Fig. 2-1E).

P.48

|

|

FIGURE 2-1

|

P.49

|

|

FIGURE 2-1 (Continued)

|

• Pearls

-

This is facilitated by fully supinating

the forearm which brings the supinator attachment of the radius easily

within the wound allowing excellent visualization for the release of

its origin. -

It is not necessary to identify the

posterior interosseous nerve during this procedure but one should be

gentle to avoid nerve injury.

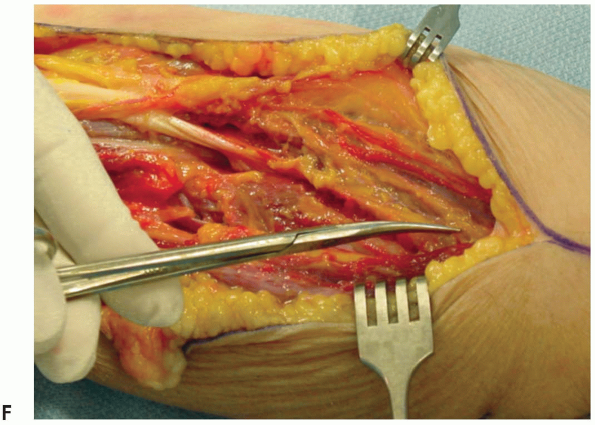

7. The supinator muscle is reflected towards its ulnar attachment and the proximal portion of the radius is exposed (Fig. 2-1F).

8. After splitting the forearm fascia distally, the

common extensor is reflected posteriorly and the tendinous portion of

the brevis and longus is isolated in the midforearm (Fig. 2-1G). The radial attachment of the pronator teres muscle is in the mid-portion of the exposure.

common extensor is reflected posteriorly and the tendinous portion of

the brevis and longus is isolated in the midforearm (Fig. 2-1G). The radial attachment of the pronator teres muscle is in the mid-portion of the exposure.

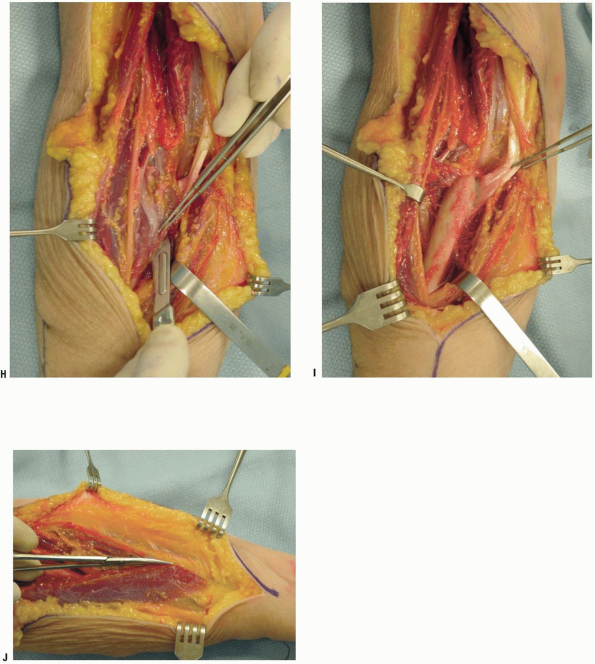

9. Distally, by retracting the extensor digitorum

communis posteriorly and extensor carpi radialis brevis anteriorly, the

abductor pollicis longus and extensor polis brevis are observed to

course obliquely superficial to the extensor carpi radialis brevis

tendon at the distal aspect of the incision (Fig. 2-1H). The middle 80% of the radius is exposed.

communis posteriorly and extensor carpi radialis brevis anteriorly, the

abductor pollicis longus and extensor polis brevis are observed to

course obliquely superficial to the extensor carpi radialis brevis

tendon at the distal aspect of the incision (Fig. 2-1H). The middle 80% of the radius is exposed.

P.50

|

|

FIGURE 2-1 (Continued)

|

P.51

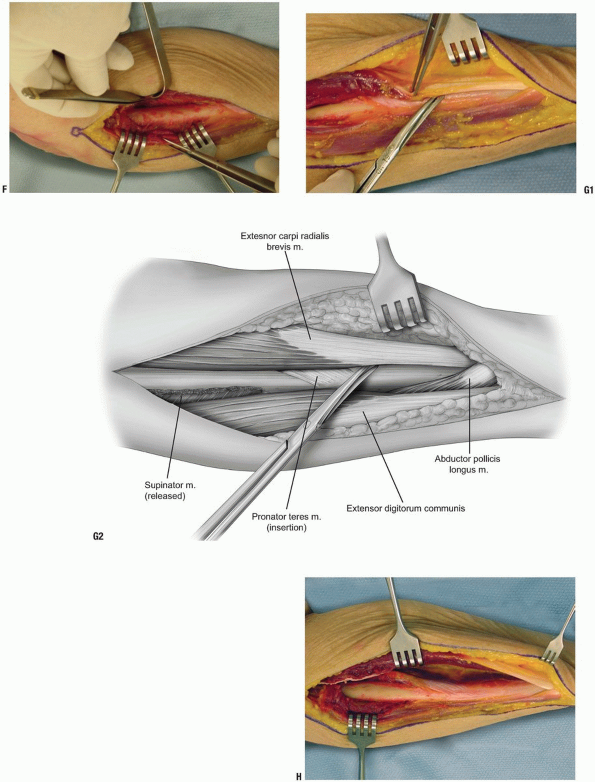

ANTERIOR (HENRY) SURGICAL EXPOSURE TO THE PROXIMAL RADIUS

Indications

Fracture, malignancy, and osteomyelitis.

Position

The patient is supine with the arm on an elbow table.

Landmarks

-

The mobile wad is identified and

palpated, the lateral aspect of the distal fourth of the biceps, the

cubital crease proximally, and the radial styloid distally are

identified (Fig. 2-2A). -

Skin incision: After splitting the

brachial fascia, the lateral margin of the biceps muscle is identified

in the proximal aspect of the wound (Fig. 2-2B). -

The interval between the biceps and brachialis is developed by blunt and sharp dissection.

-

The terminal branch of the musculocutaneous nerve is identified and protected as the skin incision extends distally (Fig. 2-2C).

-

The recurrent branch of the radial artery is identified and ligated (Fig. 2-2D).P.52

-

Pearl: This is the key step that allows distal expansion of this exposure.

-

-

The origin of the biceps on the radial

tuberosity is identified medially. Laterally the brachioradialis muscle

is observed along with the radial nerve (Fig. 2-2E) that travels in the interval between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles proximally.-

Note: Observe proximacy of posterior interosseous nerve to the anterior capsule over the radial head.

-

-

The forearm fascia is split distally between the pronator teres medially and the brachioradialis muscle laterally (Fig. 2-2F).

The pronator teres muscle belly is followed distally and is retracted

exposing the supinator muscle and the pronator attachment. -

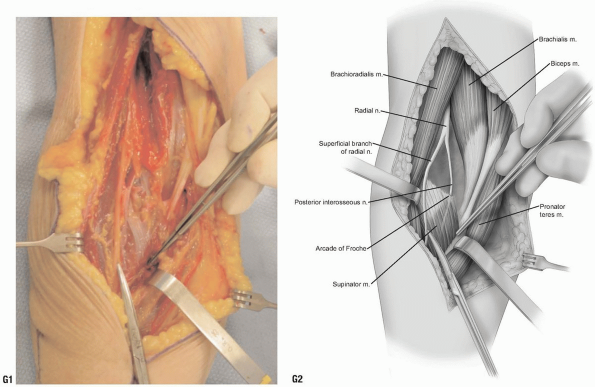

By supinating the forearm, the radial

origin of the supinator muscle is identified. The posterior

interosseous nerve is observed entering under the arcade of Froche (Fig. 2-2G). The superficial radial nerve is identified on the undersurface of the brachioradialis and protected. -

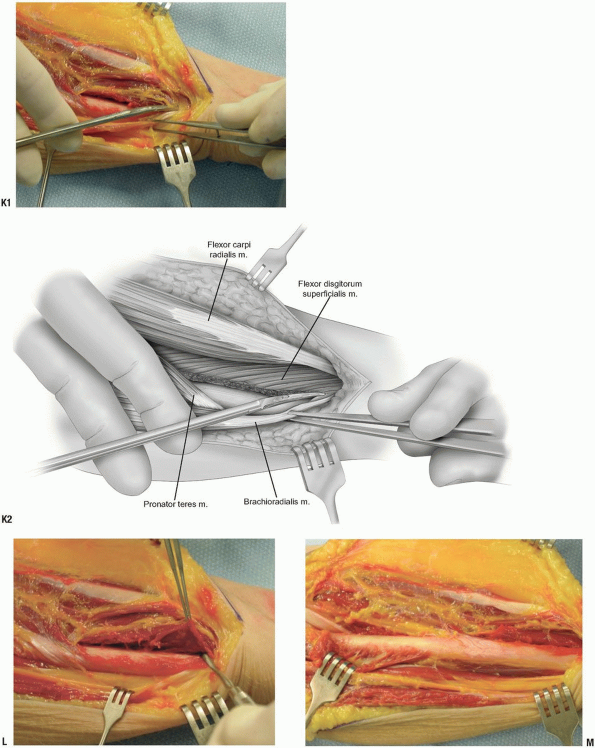

The supinator muscle is released from the proximal radius, exposing the anterior aspect of the proximal radius (Fig. 2-2H,I).

-

The fascia between the brachioradialis and the pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis is split distally (Fig. 2-2J).

-

The brachioradialis along with the radial

nerve is retracted laterally, the pronator teres and flexor carpi

radialis muscles are retracted medially. The insertion of the pronator

teres is identified at the proximal aspect of the dissection (Fig. 2-2K). -

Pronation of the forearm allows

visualization of the attachment of the pronator teres and flexor

pollicis longus. Distally the pronator quadratus is elevated from the

medial aspect of the radius (Fig. 2-2L). -

By supinating the forearm, sharp

periosteal elevation of all remaining muscular attachments of the

radial shaft allows complete exposure of the radius (Fig. 2-2M).

|

|

FIGURE 2-2

|

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.53

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.54

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.55

|

|

FIGURE 2-2F (Continued)

|

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.56

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.57

|

|

FIGURE 2-2 (Continued)

|

P.58

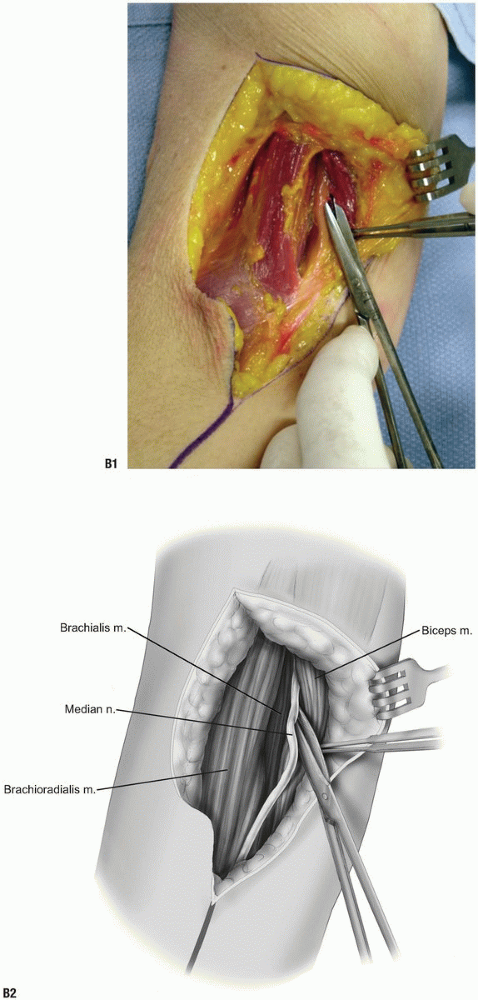

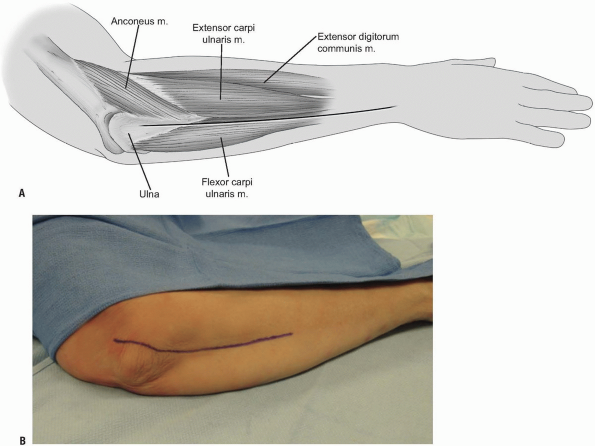

EXPOSURE OF THE SHAFT OF THE ULNA

This is probably the easiest exposure of the entire

musculoskeletal system as the ulna lies in a subcutaneous position

throughout its course and there are no neurovascular structures at risk

(Fig. 2-3A).

musculoskeletal system as the ulna lies in a subcutaneous position

throughout its course and there are no neurovascular structures at risk

(Fig. 2-3A).

Indication

Fracture and revision of ulnar component.

Position

The patient is prone with forearm across the chest.

Landmarks

Tip of olecranon, subcutaneous border of ulna, and ulnar styloid.

|

|

FIGURE 2-3

|

P.59

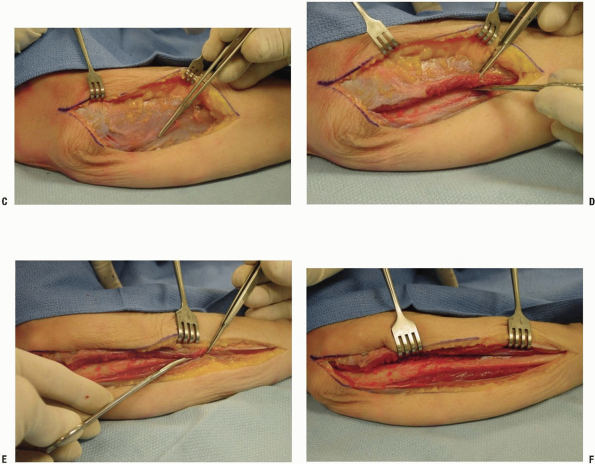

Technique

-

Incision: A straight incision from the

medial or lateral aspects of the olecranon or originating directly over

the olecranon, proceeds distally to the ulnar styloid, as needed (Fig. 2-3B). -

The subcutaneous border of the ulna is easily palpated (Fig. 2-3C).

-

Elevating the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris muscles allows exposure of the radial side of the ulna (Fig. 2-3D).

-

The flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor

digitorum profundus muscles attach to the medial aspect of the ulna and

are freed subperiosteally (Fig. 2-3E). -

The dissection extends distally as far as is needed (Fig. 2-3F).

|

|

FIGURE 2-3 (Continued)

|

P.60

RECOMMENDED READING

Anson BJ, Maddock WG. Callander’s Surgical Anatomy, 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1958.

Banks S, Laufman H. An Atlas of Surgical Exposures of the Extremities. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1953.

Campbell WC. Incision for exposure of the elbow joint. Am J Surg 1932;15:65-67.

Grant JCB. An Atlas of Anatomy, 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1972.

Gray H. The Anatomy of the Human Body, 29th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1975.

Henry AK. Extensile Exposure, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, Inc., 1963.

Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons: The Back and Limbs, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Harper & Row, 1982.

Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomical Approach, 1st ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co., 1984.

Kaplan EB. Surgical approach to the proximal end of the radius and its use in fractures of the head and neck of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg 1941;23:86-92.

Kocher T. Textbook of Operative Surgery [translated from 4th German edition by HJ Stiles]. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1903.

Morrey BF. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery: The Elbow, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Reckling FW, Reckling JB, Mohr MC. Orthopedic Anatomy and Surgical Approaches. St. Louis: Mosby Yearbook, 1990.

Thompson JE. Anatomical methods of approach in operations on the long bones of the extremities. Ann Surg 1918;68:309-329.

Tubiana R, McCullough CJ, Masquelet AC. An Atlas of Surgical Exposures of the Upper Extremity. London: Martin Dunitz Publisher, 1990.