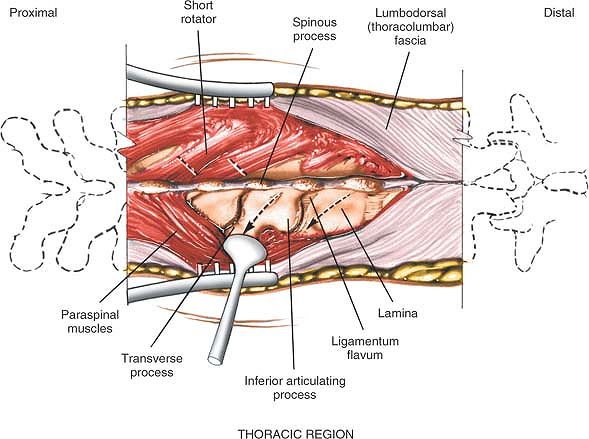

The Spine

The cervical spine is light, small, and flexible; the thoracic spine is

larger and relatively immobile because of its associated ribs. The

lumbar spine, especially the lower part, has more mobility than the

thoracic spine, but less than the cervical spine. Pathology is seen

most commonly in the cervical and lumbar spines, which are the most

mobile portions of the axial skeleton; they require surgery most

frequently.

through either an anterior or a posterior approach to treat pathology

of its anterior and posterior elements. Pathologies such as vertebral

body infection, fracture, and tumor often require anterior approaches.

There are many anterior approaches to the spinal column; we present the

basic ones that allow access to all the anterior parts of the spine.

posterior approaches are the most common, permitting access to all the

posterior spinal elements, as well as to the spinal cord and

intervertebral discs.

the ilium is the best site from which to obtain bone graft material,

this chapter concludes with the anterior and posterior approaches to

the ilium that are used in conjunction with spinal approaches.

the lumbar spine. Besides providing access to the cauda equina and the

intervertebral discs, it can expose the posterior elements of the

spine: the spinous processes, laminae, facet joints, and pedicles. The

approach is through the midline, and it may be extended proximally and

distally.

-

Excision of herniated discs1

-

Exploration of nerve roots2

-

Spinal fusion3,4

-

Removal of tumors5

-

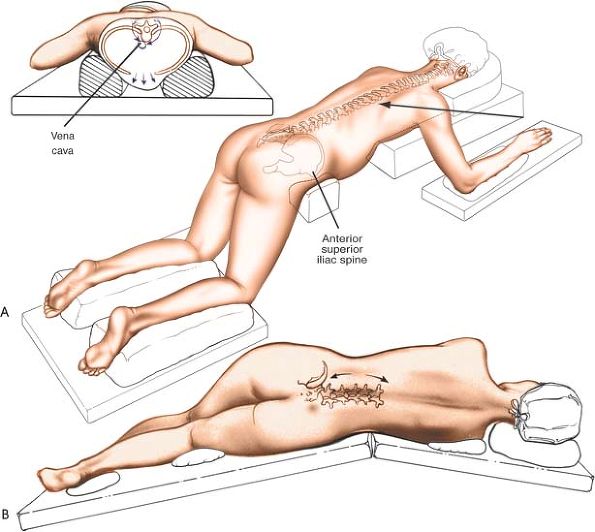

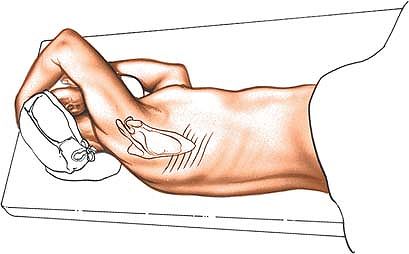

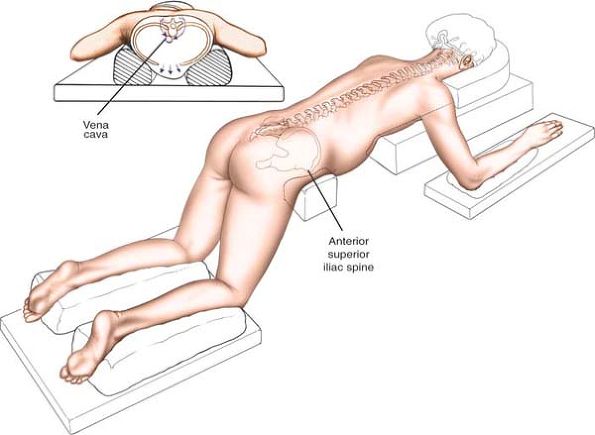

Logroll the patient into a prone

position. Be sure that bolsters are placed longitudinally under the

patient’s sides to allow the abdomen to be entirely free, reducing

venous plexus filling around the spinal cord by permitting the venous

plexus to drain directly into the inferior vena cava. The shoulders

should be placed at no more than 90° of abduction and should be

slightly flexed forward to relax the brachial plexus. Careful padding

of the ulnar nerve at the elbow and median nerve at the wrist must be

assured. Position the head and neck in a relaxed, neutral position and

be sure that no pressure is applied to the eyes. The lower extremities

should be padded carefully at the knees and feet. The hips are usually

flexed for decompression, as it allows for an increase in interlaminar

or interspinous distance and in neutral or slight extension for lumbar

fusions to restore normal lordosis. The knees are flexed, and we must

check that there is no pressure on the proximal fibula/common peroneal

nerve region (Fig. 6-1A). -

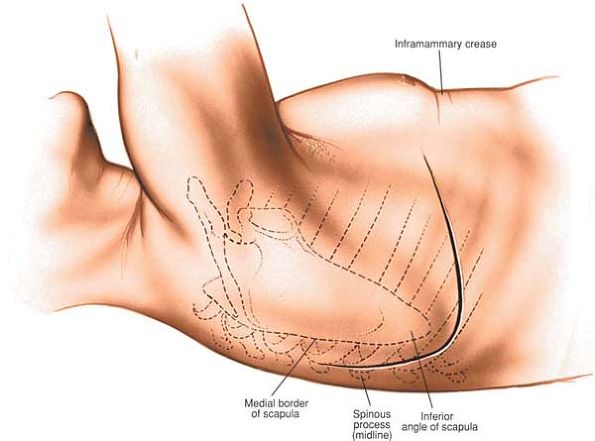

Place the patient on his or her side,

with the affected side upward. Flex the patient’s hips and knees to

flex the lumbar spine and open up the interspinous spaces. Make sure

that the patient is positioned with the involved spinal level over the

table break. Jackknifing the table can open further the intervertebral

space on the upper side of the patient by putting the lumbar spine into

lateral flexion. One advantage of this position is that it allows the

surgeon to sit. Extravasated blood drains down, away from the operative

field (see Fig. 6-1B).

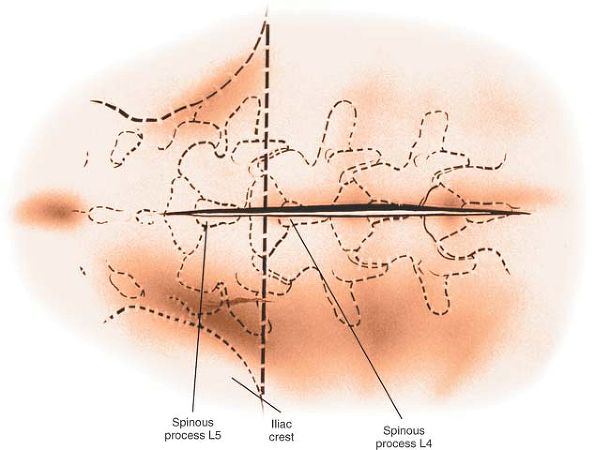

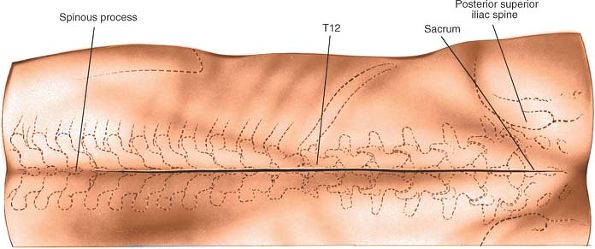

is in the L4-5 interspace. The line is only a rough guide, however; the

best means of determining the exact level is either to insert a small

needle into the spinous process and obtain a radiograph or to carry the

dissection distally and identify the sacrum.

above to the spinous process below the pathologic level. The length of

the incision depends on the number of levels to be explored (Fig. 6-2).

|

|

Figure 6-1 (A) The position of the patient for the posterior approach to the lumbar spine. (B) Alternatively, place the patient in the lateral position with the affected side up.

|

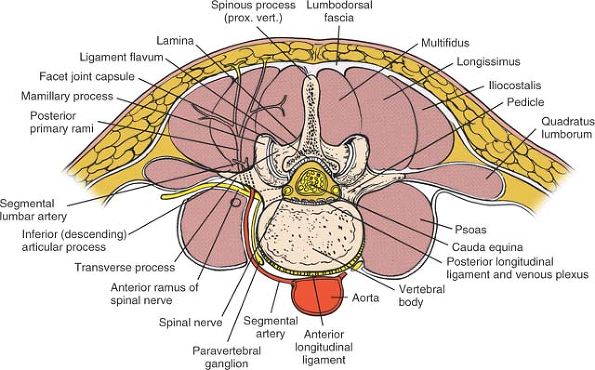

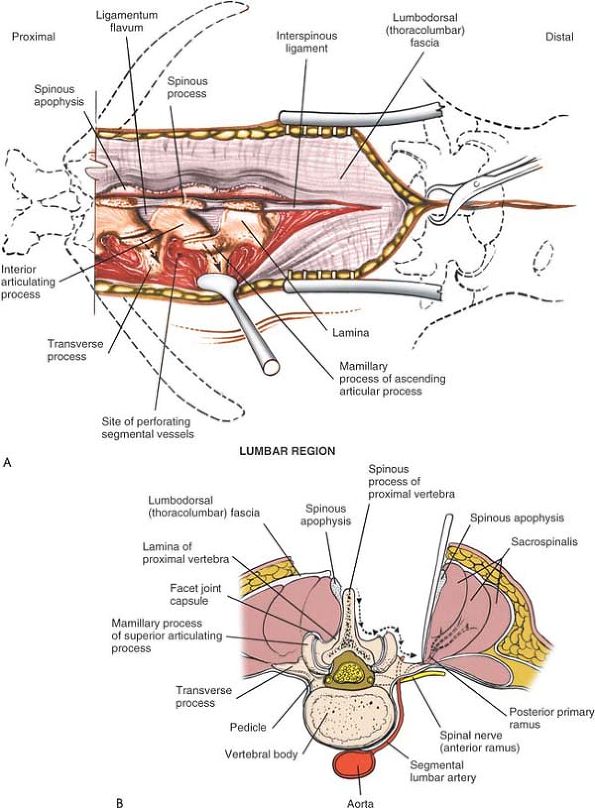

muscles (erector spinae), each of which receives a segmental nerve

supply from the posterior primary rami of the lumbar nerves.

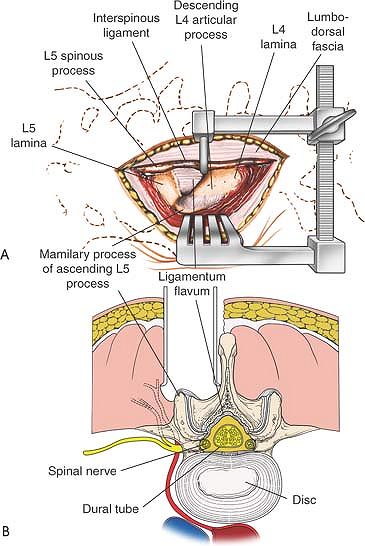

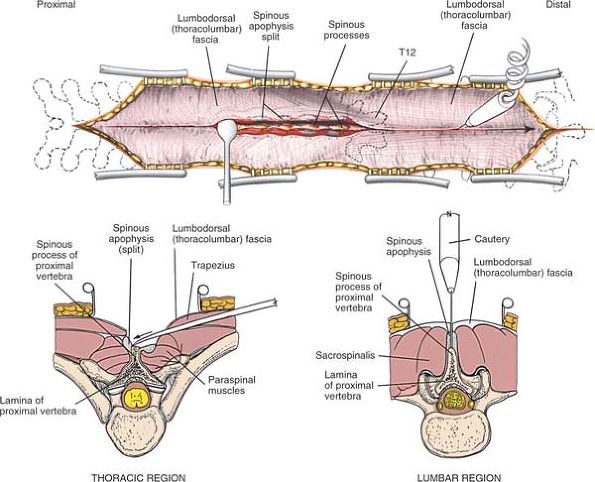

the skin incision until the spinous process itself is reached. Detach

the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally as one unit from the bone, using

a dissector, such as a Cobb elevator, or with cautery (Fig. 6-3).

Dissect down the spinous process and along the lamina to the facet

joint. In a young patient, the tip of the spinous process is a

cartilaginous apophysis; it can be split in the midline, making

subperiosteal muscle removal easier (Fig. 6-4).

stripping the facet joint capsule from the descending and ascending

facets. To do this, strip the joint capsule in a medial to lateral

direction across the posterior aspect of the descending facet; then,

continue over the tip of the mamillary process of the more lateral

ascending facet. If the transverse processes must be reached, continue

dissecting down the lateral side of the ascending facet and onto the

transverse process itself (see Fig. 6-4).

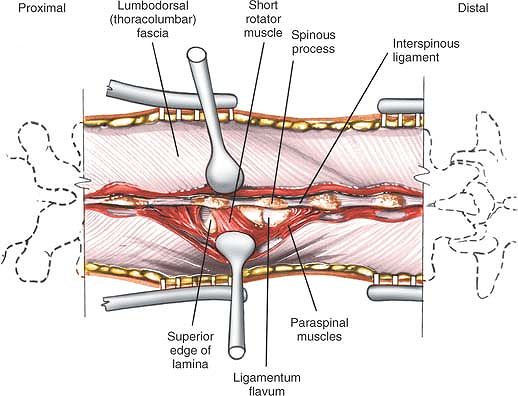

transverse processes, are the vessels supplying the paraspinal muscles

on a segmental basis. These branches of the lumbar vessels frequently

bleed as the dissection is carried out laterally. Vigorous

cauterization of these

vessels

may be necessary to stop the bleeding. Note that the posterior primary

rami of the lumbar nerves, which also supply the paraspinal muscles

segmentally, run with these vessels. Loss of some of these nerves does

not totally denervate the paraspinal muscles, because they are

innervated segmentally (see Fig. 6-4).

|

|

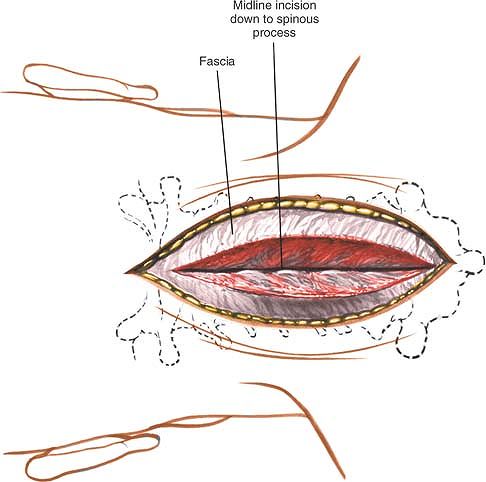

Figure 6-2

Make a longitudinal incision over the spinous processes, extending from the spinous process above to the spinous process below the level of pathology. A line drawn across the highest point of the iliac crest is in the L4-5 interspace. |

|

|

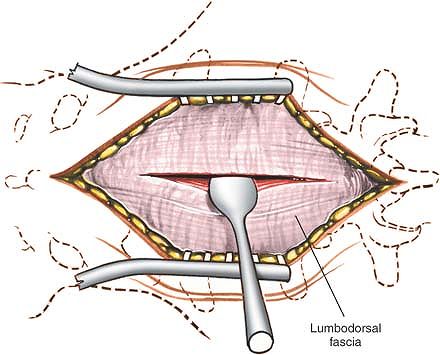

Figure 6-3

Deepen the incision through the fat and fascia in line with the skin incision until the spinous process itself is reached. Detach the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally. |

|

|

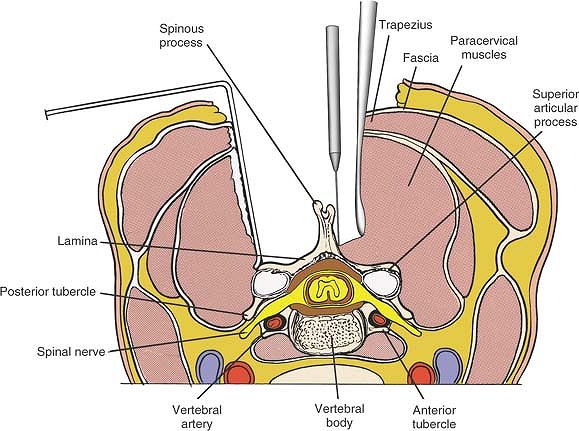

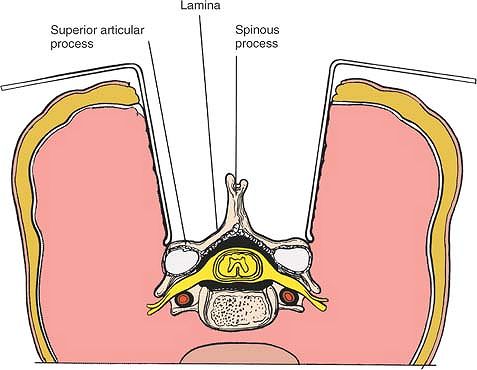

Figure 6-4 (A)

Dissect the paraspinal muscles from the spinous process and lamina to the facet joint. Remove the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally as one unit from the bone. (B) Continue dissecting laterally, stripping the joint capsule from the descending and ascending facets. Note the branches of the lumbar vessels that bleed during stripping of the muscles. |

|

|

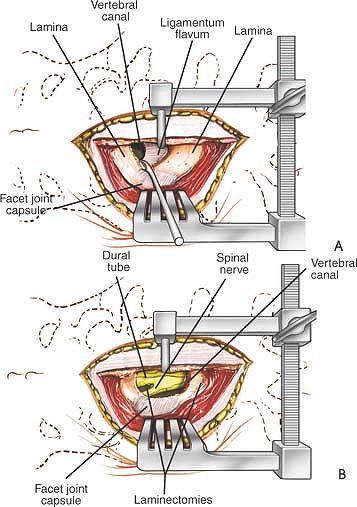

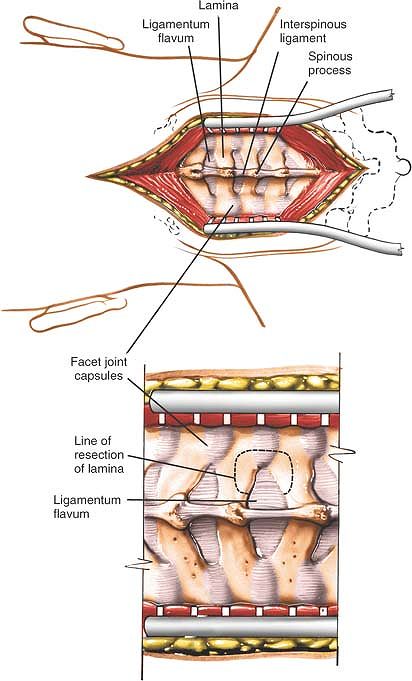

Figure 6-5 (A) Remove the ligamentum flavum by cutting its attachment to the superior or leading edge of the inferior lamina. (B)

Immediately beneath the ligamentum flavum and epidural fat is the blue-white dura. Identify the nerve root. Note the overlying epidural veins. |

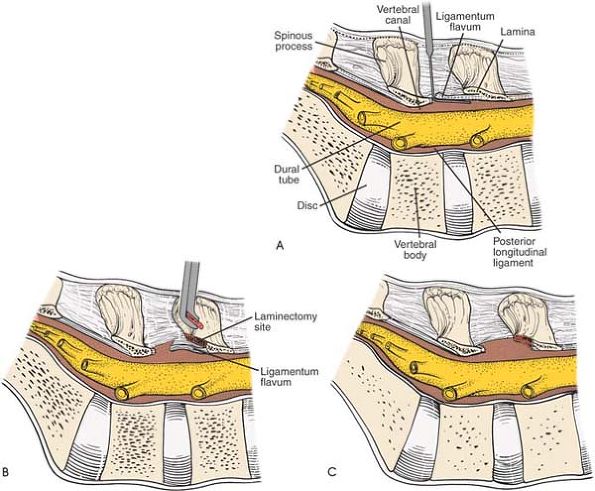

to the superior, or leading, edge of the inferior lamina using either a

curette or sharp dissection. Immediately beneath are epidural fat and

the blue-white dura. Using blunt dissection and staying lateral to the

dura, carefully continue down to the floor of the spinal canal,

retracting the dura and its nerve root medially (Figs. 6-5, 6-6, 6-7 and 6-8).

protected. The more lateral the surgical field, the easier it is to

identify the nerve root and retract it so the disc space can be seen.

If a larger exposure is needed, incise part of the lamina on the distal

portion of the involved vertebra.

The bleeding can be stopped with Gelfoam or cotton patties soaked in

thrombin. Bipolar Malis cautery also may be used, although it must be

done with

great care because of the proximity of the nerve roots.

|

|

Figure 6-6 (A) Insert a blunt dissector under the cut edge of the ligamentum flavum. (B)

Use a Kerrison rongeur to remove the distal end of the lamina. Note that the ligamentum flavum attaches halfway up the undersurface of the lamina. (C) Remove additional lamina and the remaining portion of the ligamentum flavum at its attachment to the undersurface of the lamina. |

the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies may be injured if

instruments pass through the anterior portion of the annulus fibrosus

(see Fig. 6-21).6

-

To gain better exposure of the dura,

nerve root, and disc, remove additional portions of the lamina, both

from the leading edge of the lamina below and from the caudal edge of

the lamina above. A portion of the facet joint itself even can be

removed. Remember that it is safer to remove bone than to retract nerve

roots or dura excessively. If the wound is tight, dissect the

paraspinal muscles off the posterior spinal elements above and below

the exposed level to make the muscles easier to retract. -

To gain access to other parts of the

posterior aspect of the spine, carry the dissection as far laterally as

possible, onto the transverse processes. Complete lateral dissection

exposes the facet joints and transverse processes, permitting facet

joint fusion and transverse process fusion, if necessary (see Fig. 6-4).

proximally or distally and detach the posterior spinal musculature from

the posterior spinal elements. The approach can be extended from C1

down to the sacrum.

|

|

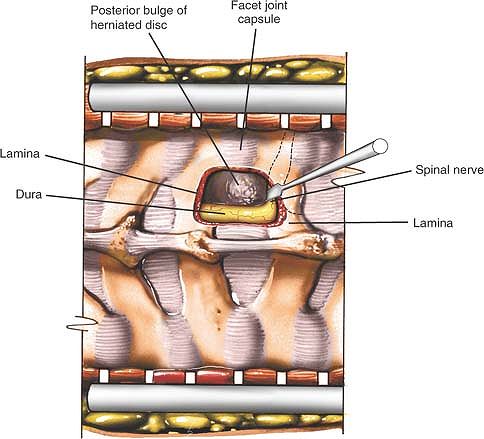

Figure 6-7 (A)

Using blunt dissection, carefully continue down the lateral side of the dura to the floor of the spinal canal; retract the dura and its nerve root medially. Reveal the posterior aspect of the disc. (B) Cross-section revealing the retraction of the dural tube and a herniated nucleus pulposus impinging on a nerve root. |

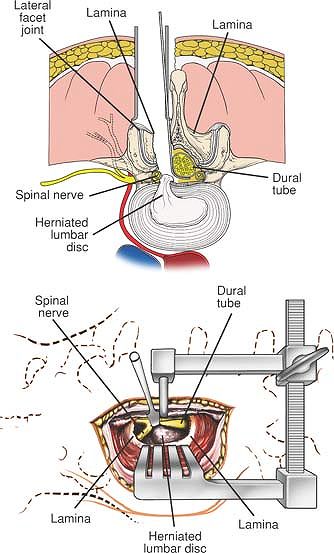

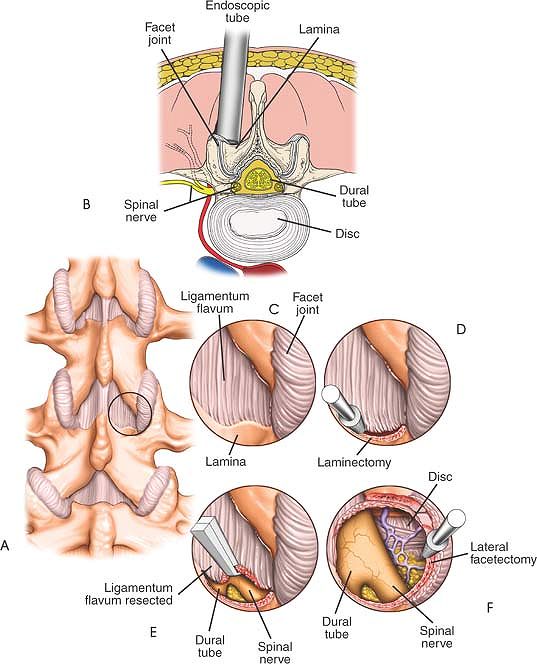

dilating/retracting tube and abutted against the lamina and medial

facet joint.7 The distal lamina and

ligamentum flavum are resected on the affected side to expose the nerve

root over the disc. Some of the medial facet can be resected to

decompress the lateral recess. The nerve root is then retracted

medially to expose the pathologic disc (Fig. 6-9).

|

|

Figure 6-8 With the use of a microscope and retractor, a 3-cm incision can be used to expose the disc at a single level.

|

with landmarks and fluoroscopy because a very small incision is made.

Any deviation from the planned course may make it difficult to find the

pathology. If the incision is too medial, the spinous processes may

impede the proper positioning of the retracting tube. A tube that is

angled excessively will make it difficult to work and target the

microscope. This can be mitigated by using a tilting operating table.

Meticulous hemostasis is important, as the small access port can be

obscured easily by excessive bleeding.

differently to address pathologies in different locations, for example,

to access a sequestered disc, a far lateral disc, or to decompress a

contralateral spinal stenosis. Larger tubes are available if more

exposure is required. In the lordotic spine, a small change in the

angle of the tube can permit access to an adjacent level.

|

|

Figure 6-9 (A)

Localization of the level is performed with fluoroscopy. The starting point is 2 cm from the midline directly above the involved disc. (B) A 1- to 2-cm incision is made longitudinally. The fascia is incised. The erector muscles are split bluntly with dilating tubes. The retracting tube is positioned at the intersecting point of the lamina above the facet laterally and the ligamentum flavum medially and distally. (C) The proximal and distal lamina are thinned with a high speed burr. (D) The ligamentum flavum can be retracted medially or simply resected with a Kerrison rongeur is used to resect the caudad aspect of the lamina. (E) The ligamentum flavum can be retracted medially or simply resected with a Kerrison rongeur, exposing the dura. (F) The nerve root is exposed with the affected disc directly ventral to it. |

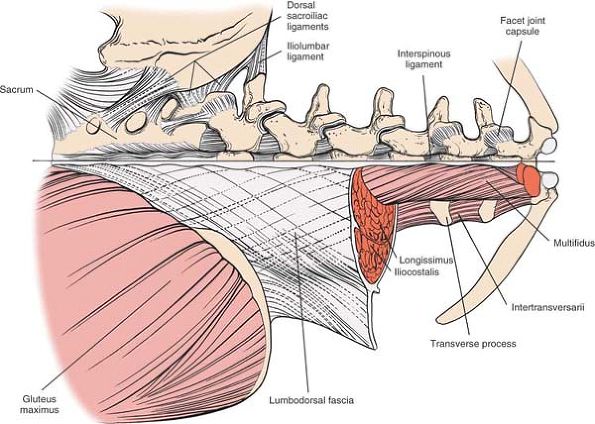

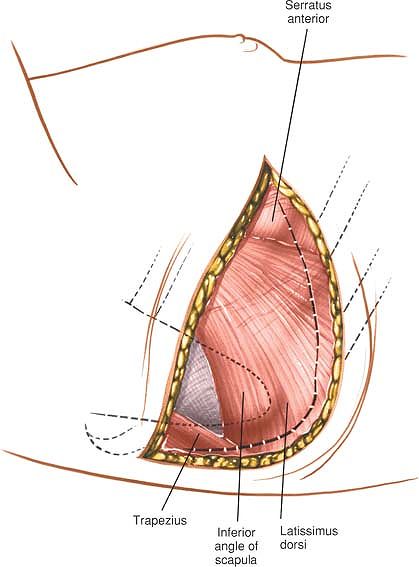

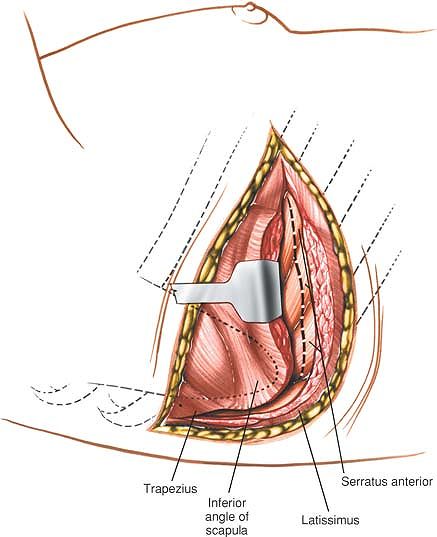

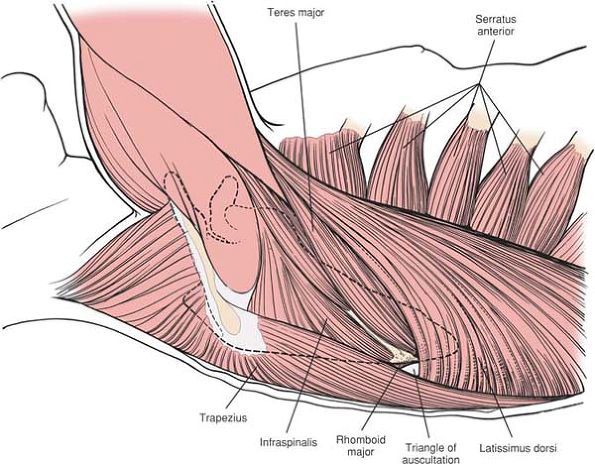

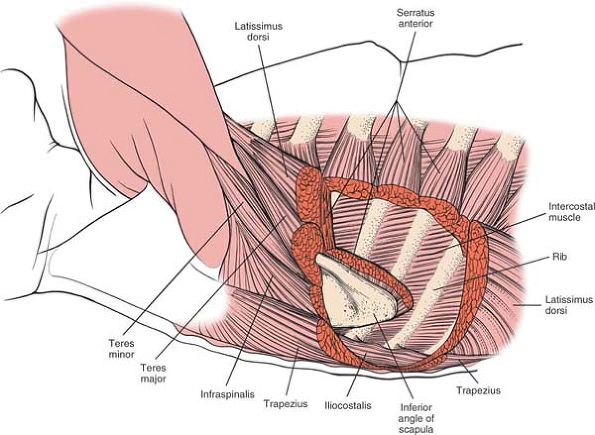

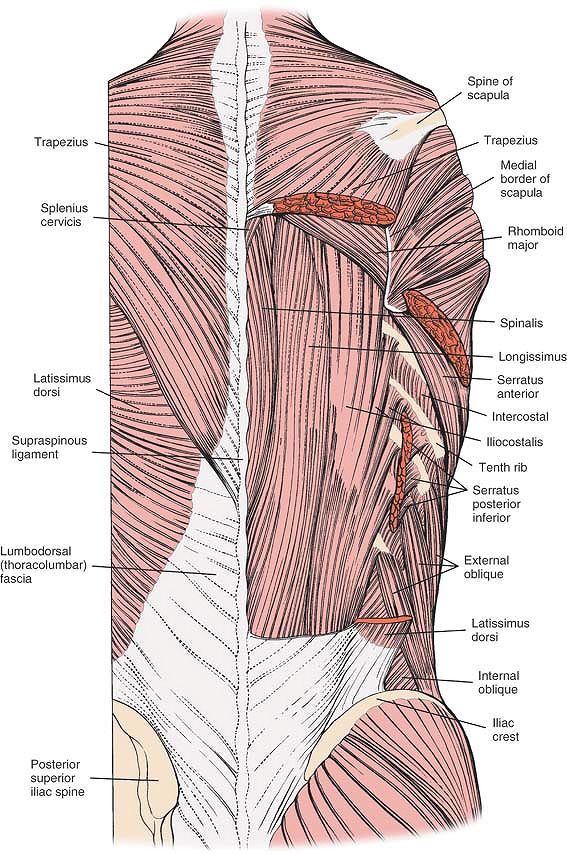

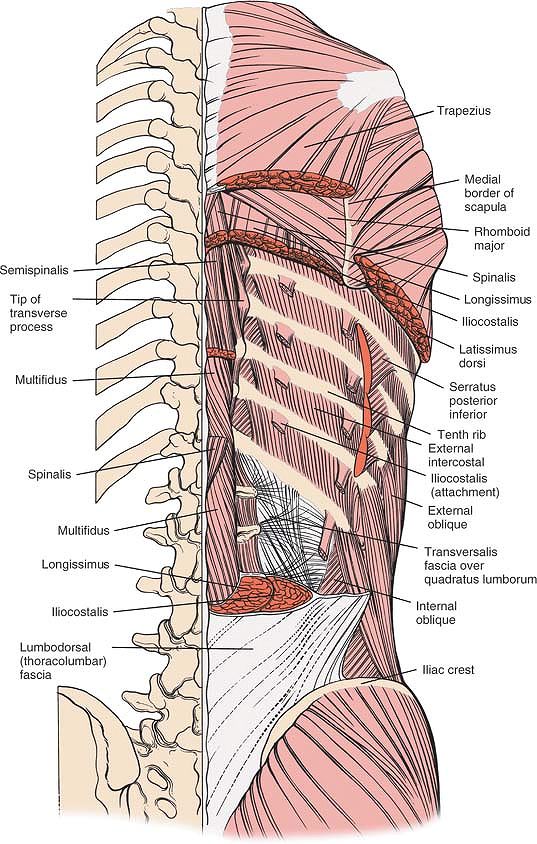

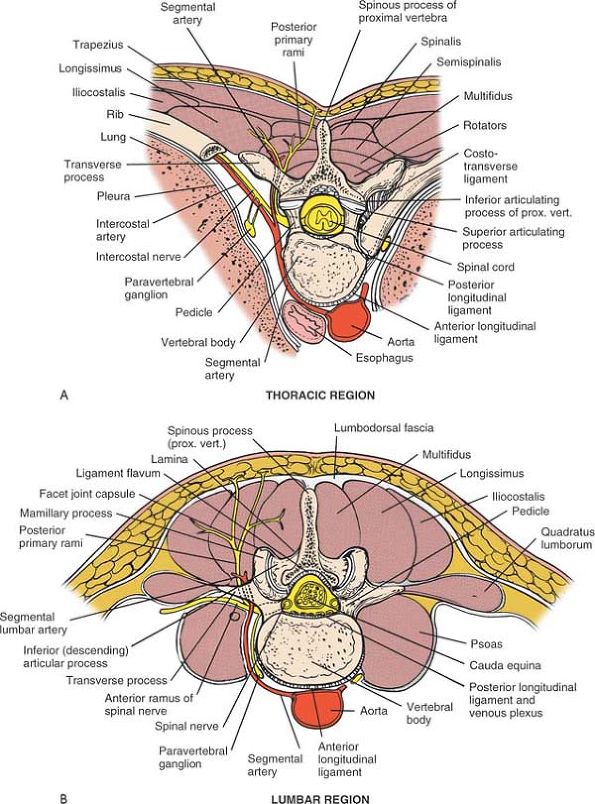

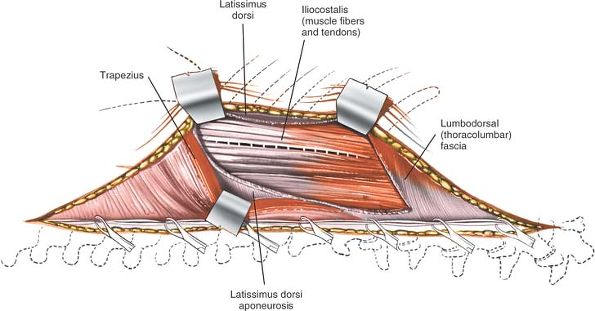

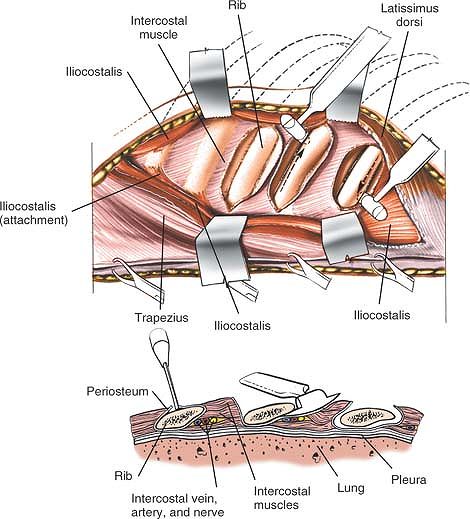

superficial and deep layers. The superficial layer consists of the

latissimus dorsi, a powerful muscle of the posterior axillary wall that

originates from the spinous processes and inserts into the

intertubercular groove of the humerus. The surgically important deep

layer consists of the paraspinal muscles and itself is divided into two

layers: the superficial portion, which contains the sacrospinalis

muscles (erector spinae), and the deep portion, which consists of the

multifidus and rotator muscles (Fig. 6-10).

|

|

Figure 6-10

An overview of the musculature of the lumbosacral spine. In the lumbar spine, the sacrospinalis system is composed of the multifidi, longissimus, and iliocostalis muscles. Note the intertransversarii muscles located deeper. Note the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments. |

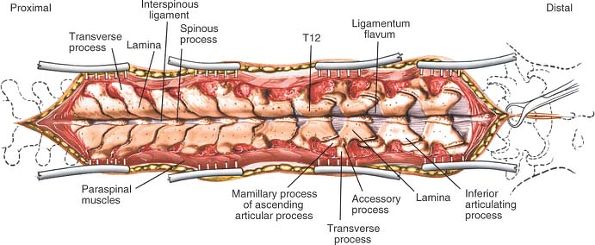

spinous processes in the lumbar area are thick. The distal end of the

tip of the spinous process is bulbous and extends slightly caudally.

Each process separates the paraspinal muscles on each side. In a

growing patient, the processes are capped by cartilaginous apophyses,

which, when split, make it easier to remove the paraspinal muscles

subperiosteally.

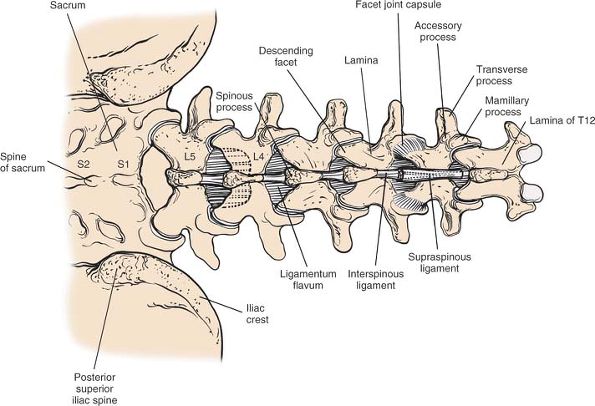

The broad iliac crests run posteriorly at a 45° angle toward the

midline. Because muscles either take origin from or insert into the

crest (none cross it), it has a palpable subcutaneous border. The

palpable, visible dimples over the buttocks lie directly over the

posterior superior iliac spines. A line drawn between the two posterior

superior iliac spines crosses the second part of the sacrum; a line

drawn between the highest points of the iliac crest crosses between the

spinous processes of L4 and L5 (Fig. 6-11).

|

|

Figure 6-11

The bony anatomy of the lumbosacral spine and the posterosuperior aspect of the pelvis. The facet joint capsules, ligamentum flavum, and interspinous ligaments are shown. A line drawn across the crest of the ilium intersects the L4-5 interspinous space. A line crossing the posterior superior iliac spine intersects the second part of the sacrum. |

processes. It tends to heal with a fine, thin scar, because it is not

under tension after suturing and is attached firmly to underlying

fascia. No major cutaneous nerves cross the midline.

spinous processes. The fascia is a broad, relatively thick, white sheet

of tissue that forms a sheath for the sacrospinalis muscles and

attaches to the spinous processes (see Fig. 6-10).

It extends to the cervical spine, where it becomes continuous with the

nuchal fascia of the neck. Medially, it is attached to the spinous

processes of the vertebrae, the supraspinous ligaments, and the medial

crest of the sacrum. Inferiorly, it is attached to the iliac crests.

Laterally, it is continuous with the origin of the aponeurosis of the

transversus abdominis and latissimus dorsi muscles.

vertebra, connecting the spinous processes. They blend intimately with

the attachment of the dorsal lumbar fascia to the spinous processes (Fig. 6-14).

of muscle from bone. Because these muscles are detached in a single

mass, their critical feature, in regard to their surgical anatomy, lies

in their blood supply and not in their structure. The segmental lumbar

vessels branch directly from the aorta. They wrap around the waist of

each vertebral body and then ascend close to the pedicle, where they

divide into two branches. One supplies the spinal cord; the other,

larger branch then comes directly posteriorly to supply the paraspinal

musculature. During the approach, these vessels appear between the

transverse processes, close to the facet joints (see Fig. 6-11).

They often bleed as dissection is carried out. In addition, the

arteries branch within the muscle bodies, frequently creating a very

vascular field. For this reason, the dissection should be kept as close

to the midline as possible; no major vessels cross the midline, and the

plane is safe for use (Fig. 6-13; see Fig. 6-11).

|

|

Figure 6-12

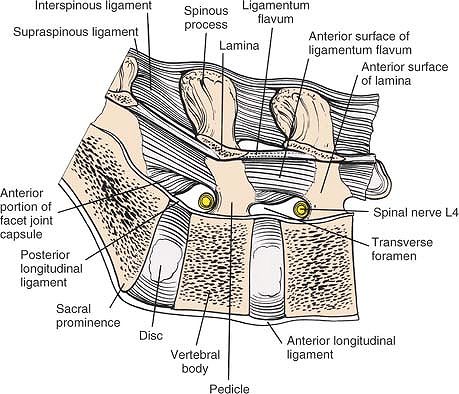

A sagittal section through the lamina of a lumbar vertebra. Note the origin and insertion of the ligamentum flavum as well as the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments. The nerve roots exit at the inferior aspect of the pedicle. |

the deep layer. Consisting of yellow elastic tissue, the ligament takes

origin from the leading edge of the lower lamina and inserts into the

anterior surface of the lamina above, about halfway up onto a small

ridge (Fig. 6-12). The two ligamenta flava, one

from each side, meet in the midline, but generally do not fuse; the

plane between the ligamentum flavum and the underlying dura fat can be

entered most easily at that point. Because of its attachments, the

ligamentum flavum is removed best from the leading edge of the lower

lamina through sharp dissection or curettage (see Fig. 6-5A).

to the dura. Once the ligamentum flavum is entered, a thin spatula

should be placed beneath it to protect the underlying dura from being

torn (see Fig. 6-6A). The cord itself and the

nerve roots often are difficult to see as a result of bleeding from

epidural veins. The veins, which are thin-walled and easy to rupture,

even with blunt dissection, can be controlled by direct pressure using

a pattie or by bipolar cautery.

|

|

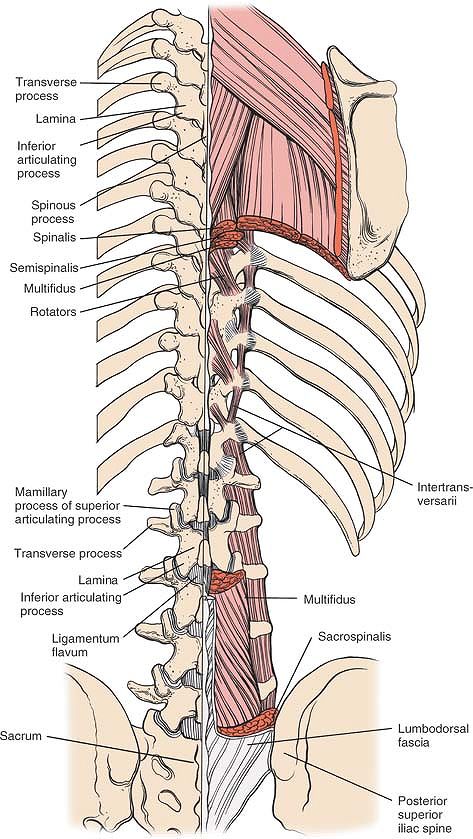

Figure 6-13

Cross-section at the L3-4 disc space, looking distally. The segmental lumbar vessels branch directly from the aorta. They wrap around the waist of each individual vertebral body and then ascend close to the pedicle, where they divide into two branches. One branch supplies the cord; the other, larger branch proceeds directly posterior to supply the paraspinal musculature. During the surgical approach, these vessels appear between the transverse processes, close to the facet joints. Note that the posterior primary rami and the posterior branches of the lumbar vessels appear between the transverse processes close to the pedicle and descending facet. |

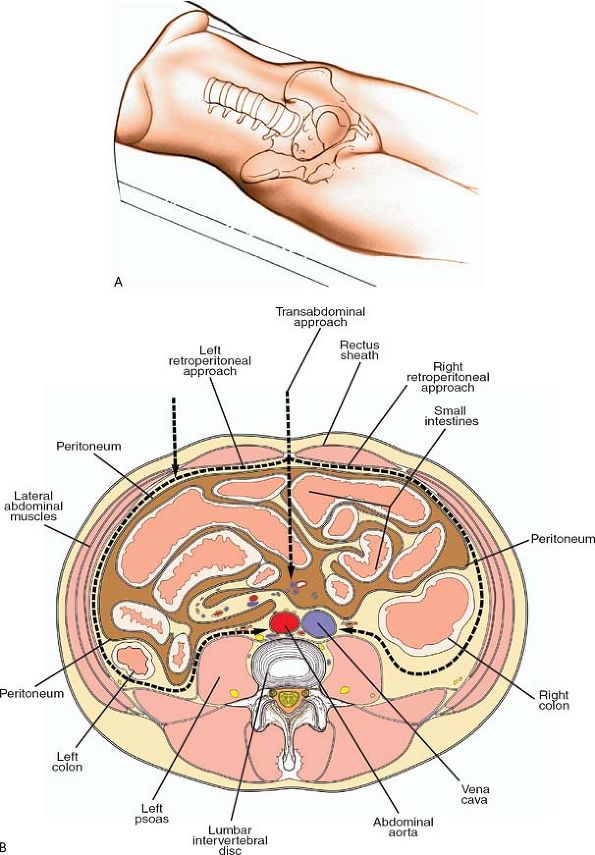

spine usually is reserved for fusing L5 to S1. It also may be used for

fusing L4 to L5, although it then involves mobilization of the great

vessels. Although the approach is simple in concept, the occasional

user may appreciate the assistance of a general surgeon who is more

familiar with the area exposed.8,9

Make sure that two areas remain bare for incision: one for the

abdominal incision, and one for harvesting an anterior iliac crest bone

graft. Insert a urinary catheter to keep the bladder empty. Use of

mechanical calf compression is recommended to decrease the risk of

thromboembolism.

|

|

Figure 6-14 With the patient in the supine position (A), the anterior lumbar spine can be approached by a transperitoneal, left retroperitoneal, or right retroperitoneal path (B).

|

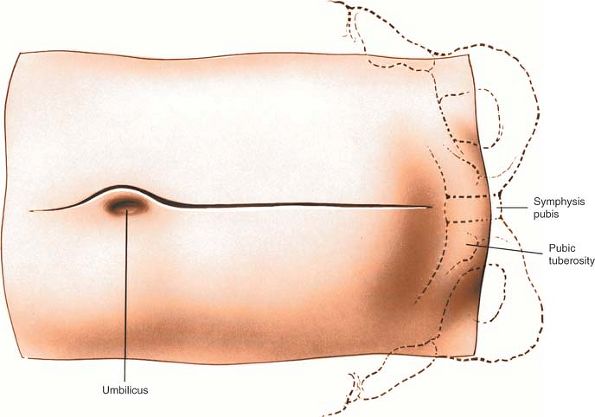

at the lower end of the abdomen through the fatty mons pubis. The pubic

tubercle, on the upper border of the pubis just lateral to the midline,

may be easier to palpate than the superior surface of the symphysis

itself.

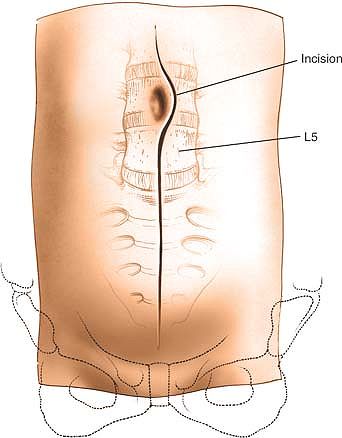

umbilicus to just above the pubic symphysis. Extend it superiorly,

curving it just to the left of the umbilicus and ending about 2 to 3 cm

above it. Heavier patients will require longer incisions (Fig. 6-15).

each side, segmentally supplied by branches from the seventh to the

12th intercostal nerves. Therefore, this incision can be extended from

the xiphisternum to the pubic symphysis.

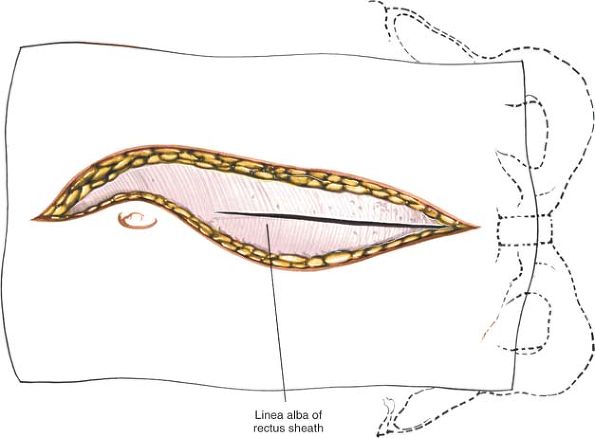

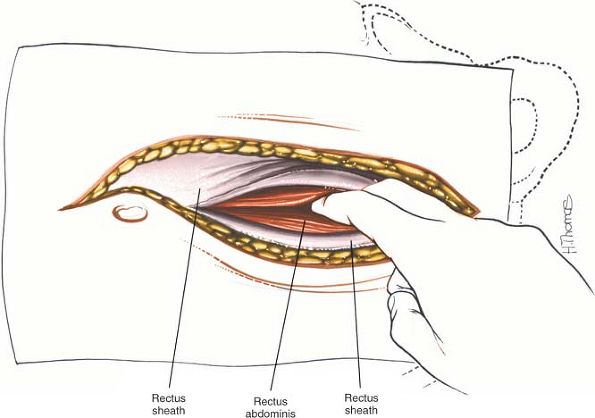

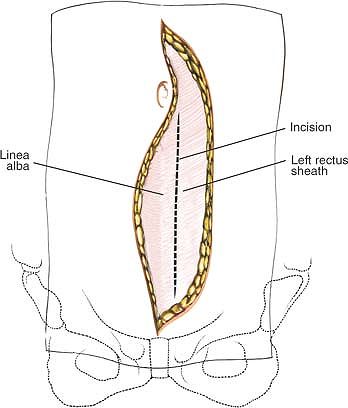

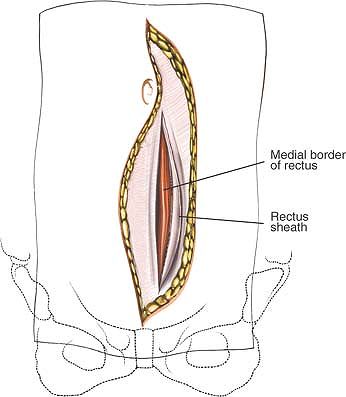

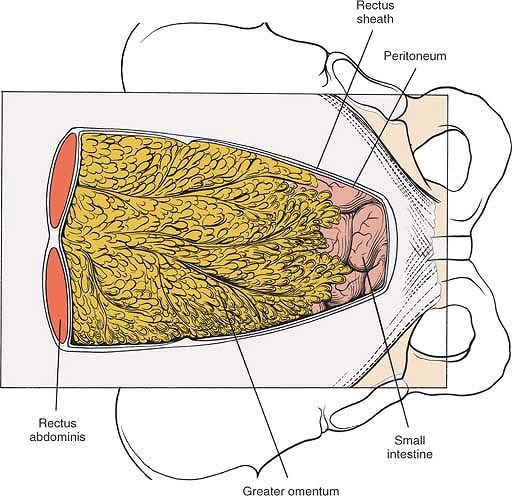

cutting through the fat to reach the fibrous rectus sheath. Incise the

sheath longitudinally, beginning in the lower half of the incision, to

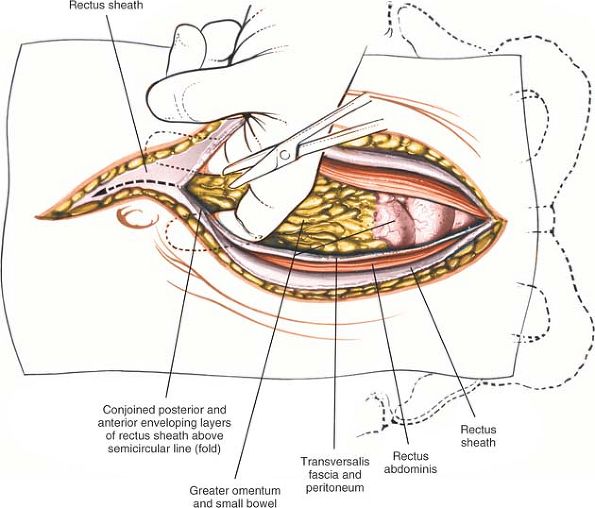

reveal the two rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 6-16). Separate the muscles with the fingers to expose the peritoneum (Fig. 6-17).

Then, pick up the peritoneum carefully between two pairs of forceps

and, after making sure that no viscera are trapped beneath it, incise

it with a scissors (Fig. 6-18). Extend the

incision distally, but take care not to incise the dome of the bladder

at the inferior end of the wound. With one hand inside the abdominal

cavity to protect the viscera, carefully deepen the upper half of the

incision, staying in the midline and cutting through the linea alba,

the band of fibrous tissue that separates the two rectus abdominis

muscles in the upper half of the abdomen. Complete the exposure by

cutting through the peritoneum in the upper half of the wound (Fig. 6-19).

|

|

Figure 6-15

Make a longitudinal midline incision from just below the umbilicus to just above the pubic symphysis. Extend it superiorly, to the left of the umbilicus. |

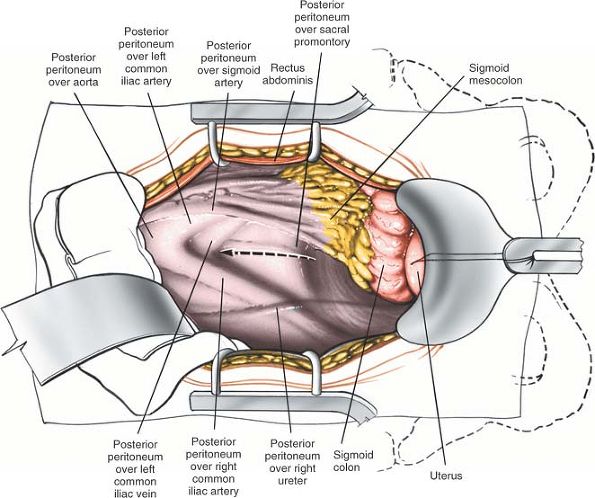

Perform a routine abdominal exploration. Next, put the operating table

in Trendelenburg’s position at 30° and carefully pack the bowel

in

a cephalad position, keeping it inside the abdominal cavity. Spread a

moist lap pad (swab) over it to prevent loops of bowel from slipping

free. It is much safer to keep the bowel within the abdominal cavity,

but do not pack it so tightly that vascular compromise is induced. In

women, the uterus may be retracted forward with a 0 silk suture placed

in its fundus and tied to the Balfour retractor.

|

|

Figure 6-16

Deepen the wound in line with the skin incision by cutting through the fat to reach the fibrous rectus sheath. Incise the sheath longitudinally. |

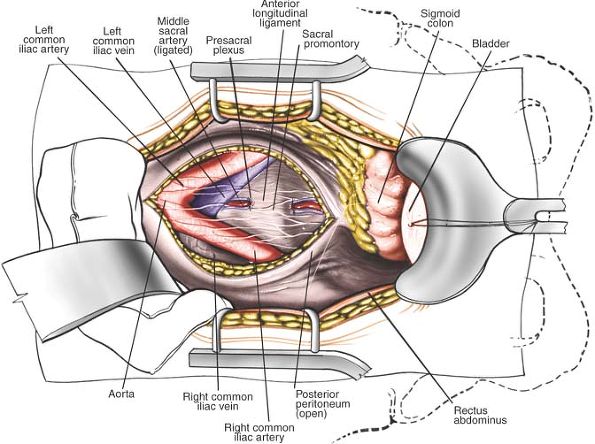

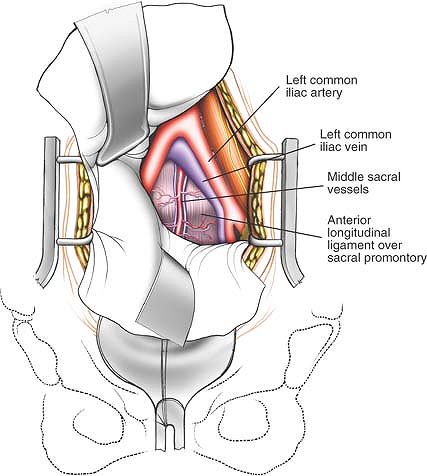

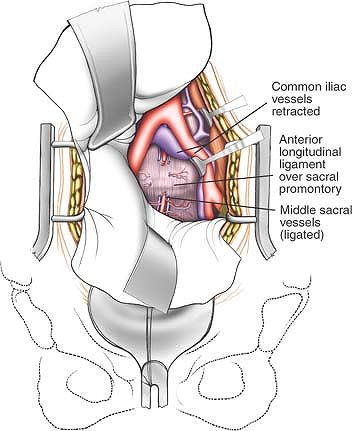

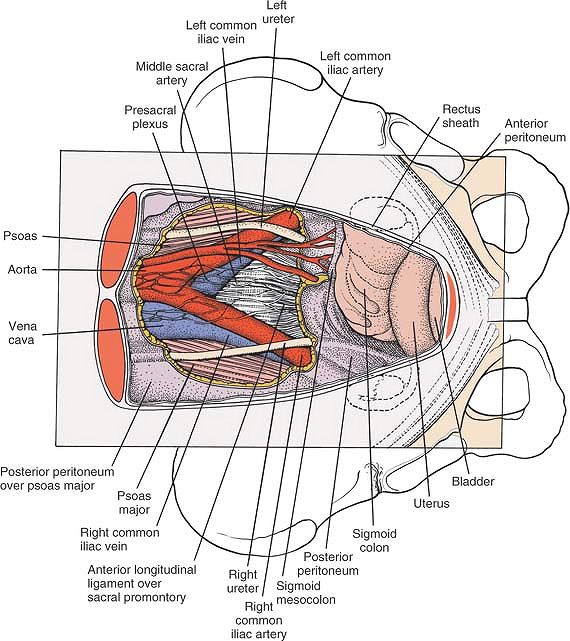

sacral promontory with a few milliliters of saline solution to make

dissection easier and to allow identification of the presacral

parasympathetic nerves that run down through this area. For the L5-S1

disc space, incise the posterior peritoneum in the midline over the

sacral promontory. The sacral artery runs down along the anterior

surface of the sacrum and must be ligated or clipped. The ureters

should be well lateral to the surgical approach.

the L5-S1 disc space either by palpating its sharp angle or by

inserting a metallic marker and taking a radiograph. The L5-S1 disc

space lies below the bifurcation of the aorta; it should be possible to

expose it fully without mobilizing any of the great vessels (Figs. 6-21 and 6-22).

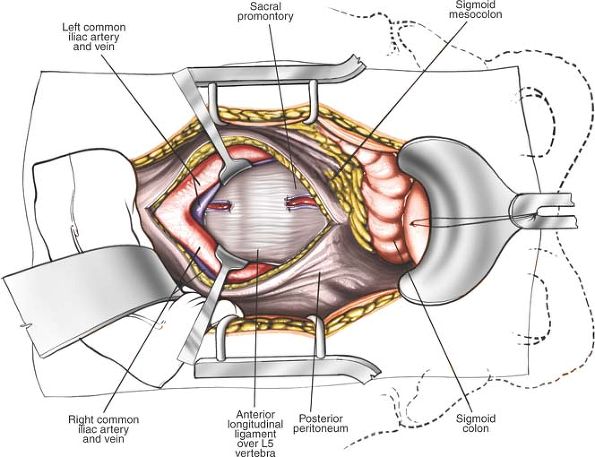

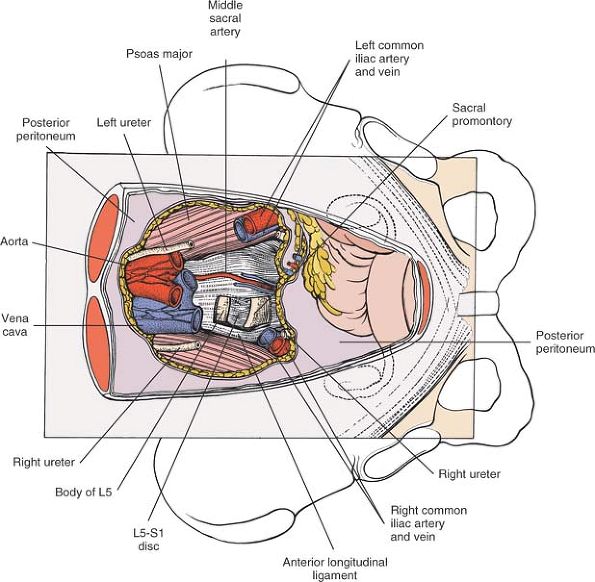

exposure; mobilizing the great vessels is necessary, unless the

vascular bifurcation occurs much higher. Carefully incise the

peritoneum at the base of the sigmoid colon and mobilize the colon

upward and to the right to expose the bifurcation of the aorta, the

left common iliac artery and vein, and the left ureter. Identify the

aorta just above its bifurcation and gently begin blunt dissection on

its left side. Identify and ligate the fourth and fifth left lumbar

vessels, then divide them. Now, the aorta, vena cava, and left common

iliac vessels can be moved to the right, exposing the L4-5 disc space.

This exposure is difficult to achieve; a high incidence of venous

thrombosis has been reported with anterior surgery at this level. Take

care not to injure the left ureter, which crosses the left common iliac

vessels roughly over the sacroiliac joint. The ureter may have to be

moved laterally, but mobilize it only as much as necessary to reduce

the risk of postoperative ischemic stricture formation.

from below, working upward into the apex of the vascular bifurcation.

Isolate the left and right common iliac artery, placing umbilicus loops

around them. Retract the two arteries cephalad and laterally

to

expose the common iliac veins. Dissect into the confluence of the veins

and isolate the left common iliac vein with a loop. Gently retract the

venous structures to expose the disc space. Use only minimal retraction

to avoid injuring the intima, which may lead to venous thrombosis (see Fig. 6-22).

|

|

Figure 6-17 With your fingers, separate the rectus abdominis muscles in the midline to expose the peritoneum.

|

|

|

Figure 6-18 Pick up the peritoneum with forceps and incise it.

|

|

|

Figure 6-19

With one hand inside the abdominal cavity to protect the viscera, carefully deepen the upper half of the incision, staying in the midline and cutting through the linea alba. |

|

|

Figure 6-20

Use a self-retaining retractor to retract the rectus abdominis muscles laterally and the bladder distally. Carefully mobilize and retract the bowel in a cephalad position, keeping it inside the abdominal cavity. Observe the posterior peritoneum overlying the bifurcation of the great vessels and the promontory of the sacrum. Incise the peritoneum longitudinally. |

critically important to sexual function. Injury to the plexus at L5-S1

may cause retrograde ejaculation and injury more distal on the sacrum

or deep in the pelvis may cause importance. Therefore, dissection

should be carried out carefully, and only with a blunt peanut

dissector. The incision over the anterior part of the sacrum should be

made in the midline, and it should be long enough to allow for lateral

mobilization of these nerves with minimal trauma. Injecting saline

solution into the presacral tissue aids in identifying and preserving

these nerves (see Figs. 6-21 and 6-34).10,11,12

are tethered to the anterior surface of the lumbar vertebrae by the

lumbar vessels. These smaller vessels must be ligated and cut to allow

the great vessels to be lifted forward off the lumbar vertebrae,

exposing the L4-5 disc space (see Fig. 6-13). It is important to dissect these vessels out carefully without cutting them flush with the aorta.

If the vessels are cut flush, there will be, in effect, a hole in the

aorta, and the bleeding may be extremely difficult to control.

Mobilization of the venous structures should be undertaken very

carefully, because they are fairly fragile and easily traumatized.

Damage to these vessels may result in thrombosis; mobilization and

retraction should be kept to a minimum.

|

|

Figure 6-21

Retract the posterior peritoneum to reveal the bifurcation of the aorta and vena cava. Ligate the middle sacral artery. Identify the presacral parasympathetic plexus overlying the aorta and the sacral promontory. |

laterally, particularly for exposure of the L4-5 disc space. It can be

identified easily by gently pinching it with a pair of non-toothed

forceps to induce peristalsis (see Fig. 6-34).

exposure in the pelvis. Careful mobilization of the great vessels is

crucial to exposure higher up (see Figs. 6-20 and 6-22).

xiphisternum, but the exposure of higher discs almost always is

performed better through a retroperitoneal approach.

|

|

Figure 6-22 Mobilize the great vessels as needed for additional exposure. Expose the L5-S1 disc space subperiosteally.

|

distal to the midway mark between the umbilicus and symphysis. A more

distal incision is required for the L5-S1 disc because of its downward

orientation. The L4-5 disc is generally located a few centimeters from

the umbilicus, and the incision is made directly over the disc. L3-4 is

a few centimeters proximal to the umbilicus and is also approached with

an incision directly over it. The incisions can be transverse if only

one level is done or the more versatile incision for one or more level

is a midline longitudinal or slight oblique incision (Fig. 6-23).13

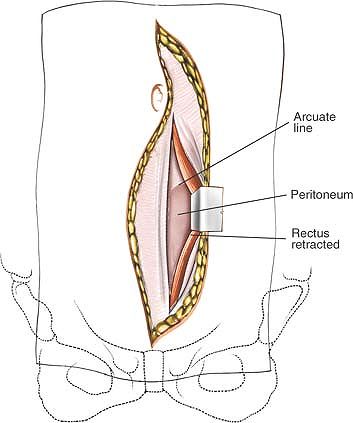

The inferior epigastric vessels are identified and preserved. Blunt

dissection is used to develop a plane dorsal to the rectus abdominis

and toward the lower quadrant. If exposing proximal to L5, the fascia

of the arcuate line is divided (Fig. 6-27).

|

|

Figure 6-23

The landmarks for an anterior minimal access retroperitoneal approach are shown. The final localization should be done radiographically prior to the incision as the disc level may vary. The incisions can be transverse, longitudinal, or slightly oblique. The incisions for L3-4 and L4-5 are generally performed directly over the disc level, whereas the L5-S1 disc must be approached through a more distal incision given the downward orientation of the disc. |

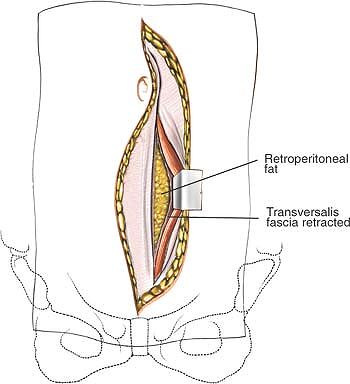

quadrant, retroperitoneal fat is eventually encountered; underneath it,

the psoas muscle can be seen. At this point, branches of the

genitofemoral nerve are readily identified lying on the psoas and just

medial is the common iliac artery. Retractors appropriate to the

direction of the incision and size should be determined (Fig. 6-28).

The ureter is generally seen on the underside of the peritoneum. The

peritoneum and ureter are retracted medially and the common iliac vein

is seen just dorsal to the artery and crossing from proximal-lateral to

distal-medial. Caution must be used not to damage the thin walls of the

vein, as it is easily the most fragile structure of this approach. The

soft tissues in front of the L5-S1 disc and sacral promontory are

bluntly pushed medially to expose the middle sacral vein(s) (Fig. 6-29).

The veins require clipping, cauterizing, and ligating to divide them

and mobilize the left iliac vein. To expose the L4-5 disc, the

dissection is moved proximal to the iliac vessels. A plane between

the

psoas and the iliac vessels is developed bluntly. The ascending

iliolumbar vein should be identified and ligated/clipped before

retracting the iliac vein.14

|

|

Figure 6-24

The incision is continued to the ventral fascia of the rectus abdominus. The midline can be identified by the crisscrossing fibers of the fascia. |

|

|

Figure 6-25 The rectus fascia is cut longitudinally on the medial edge of the muscle.

|

|

|

Figure 6-26 The medial edge is identified and the rectus is lifted up and retracted to expose the dorsal fascia and the arcuate line.

|

|

|

Figure 6-27

The epigastric vessels are identified and preserved. Blunt dissection is used to develop a plane dorsal to the rectus abdominis and toward the lower quadrant. If exposing proximal to L5, the fascia of the arcuate line is divided. |

|

|

Figure 6-28

Continuing the blunt dissection toward the left lower quadrant, retroperitoneal fat is eventually encountered; underneath it, the psoas muscle can be seen. At this point, branches of the genitofemoral nerve are readily identified lying on the psoas and just medial is the common iliac artery. |

to sexual function. Dissection should be gentle and blunt with all the

soft tissues anterior to the disc moved as a unit with the

retroperitoneum. Bipolar cautery should be used selectively.

the psoas on the lateral vertebral body particularly when exposing

proximal to L5.

anterior surface of the lumbar vertebrae by the lumbar vessels. These

smaller vessels must be ligated and cut to allow the great vessels to

be lifted forward off the lumbar vertebrae, exposing the L4-5 disc

space (see Fig. 6-13). It is important to

dissect these vessels carefully, without cutting them flush with the

aorta. If the vessels are cut flush, there will be, in effect, a hole

in the aorta, and the bleeding may be extremely difficult to control.

Mobilization of the venous structures should be undertaken very

carefully, because they are fairly fragile and easily traumatized.

Damage to these vessels may result in thrombosis; mobilization and

retraction should be kept to a minimum.

|

|

Figure 6-29

The soft tissues in front of the L5-S1 disc and sacral promontory are bluntly pushed medially to expose the middle sacral vein(s). |

retroperitoneal approach. It is generally easier to let the ureter be

moved medially with the rest of the retroperitoneum. It can be

identified by inducing peristalsis by gently pinching it with a pair of

nontoothed forceps.

aspect of T11 to S1. Exposing more proximal discs requires control and

division of the segmental vessels to mobilize the aorta and vena cava.

stages of dissection. The superficial stage consists of cutting the

skin and subcutaneous tissues down to the bowel. Below the skin lies

the linea alba, a fibrous structure in the midline that is identified

most easily in the upper abdomen. Cutting the linea alba in the lower

half of the abdomen exposes the rectus muscle, which can be separated

by finger pressure. Beneath it is the posterior rectus sheath and

peritoneum.

packing away the bowel, is the anatomy of the bowel and is not included

in this book.

retroperitoneal structures that lie anterior to the L4-5 and L5-S1 disc

spaces. These structures include the aorta, vena cava, common iliac

vessels, lumbar vessels, ureter, and presacral plexus.

|

|

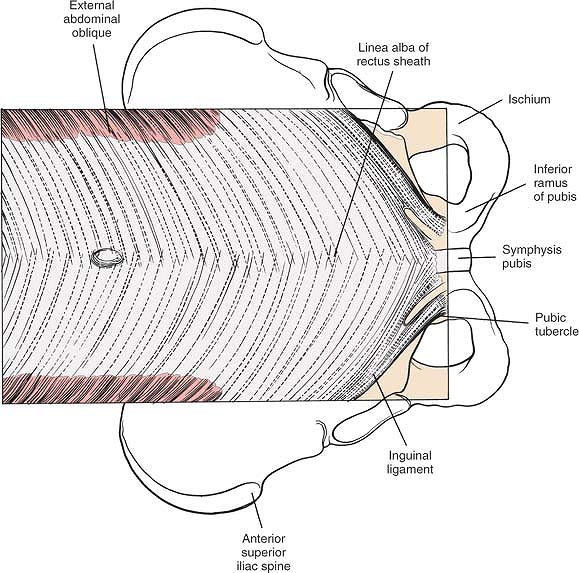

Figure 6-30 Superficial aspect of the distal rectus sheath. Note that the fibers of the external oblique appear laterally.

|

superficial to the linea alba. It usually is about halfway between the

pubic symphysis and the infrasternal notch, although it may be pulled

lower in obese patients.

externally by a groove in the midline of the abdomen. It divides one

side of the rectus abdominis muscle from the other. In the upper

abdomen, it actually separates the two muscles; cutting through it

leads directly down to the peritoneum, with neither muscle being

exposed. Below the umbilicus, the linea alba is less distinct; it does

not separate the two rectus muscles.

umbilicus. Because the skin is mobile and loosely attached to the

tissues immediately beneath it, it heals with a thin scar. The cleavage

or tension lines below the umbilicus appear in a chevron pattern, with

the apex of the V in the midline.

segmentally from T7 in the region of the xiphoid to T12 just above the

inguinal ligament. These segmental nerves do not cross the midline.

Therefore, midline incisions do not cut any major cutaneous nerves.

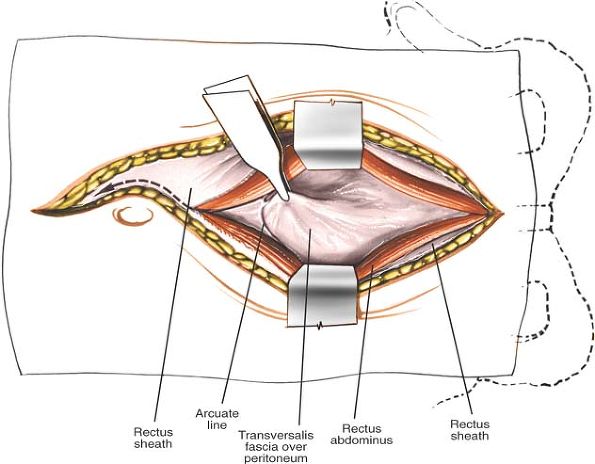

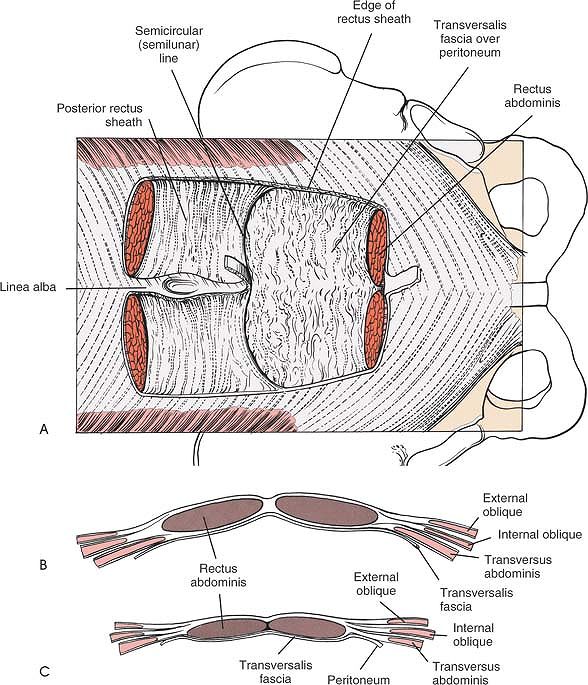

length of the entire abdomen, split into two muscles in the upper half

by the linea alba. The muscle is enclosed in a fascial sheath. Above

the umbilicus, the sheath has three elements: the aponeurosis of the

internal oblique splits to enclose the rectus muscle; the aponeurosis

of the external oblique passes in front of the rectus to form part of

the anterior sheath; and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis

fascia passes behind to form part of the posterior sheath. The inferior

margin of the posterior sheath is known as the semicircular line

(semicircular fold of Douglas). Below the umbilicus, all three

aponeuroses pass anteriorly, leaving a thin film of tissue posteriorly (Figs. 6-31 and 6-32).

|

|

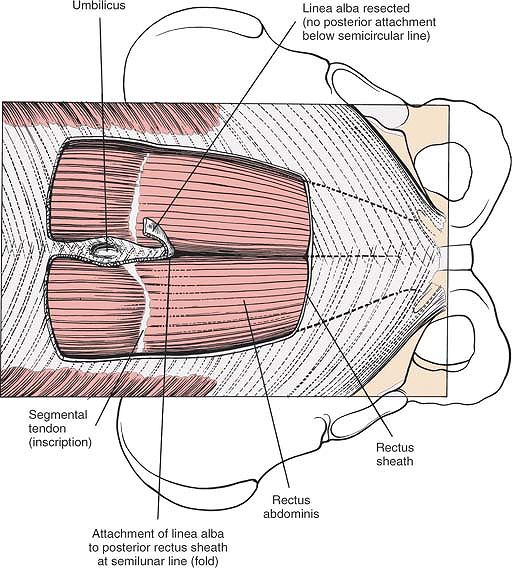

Figure 6-31

The anterior portion of the rectus sheath is resected, revealing the fibers of the rectus abdominis muscle. Distal to the semicircular line, the linea alba (which is shown elevated by sutures) overlies the muscle fibers of the rectus abdominis but does not separate them. Proximal to the semicircular line, the linea alba separates the rectus abdominis muscles by attaching to the posterior rectus sheath, which begins at the semicircular line. |

means that, in the upper half of the incision, the approach through

fibrous tissue leads directly down to the peritoneum, whereas in the

lower half, it leads to the rectus abdominis muscle. Because of this,

it is easier to open the abdomen in the lower half of the incision (Fig. 6-33; see Fig. 6-32).

|

|

Figure 6-32 (A)

The rectus abdominis muscle has been resected. The posterior aspect of the rectus sheath ends just distal to the umbilicus. Its distal edge is called the semicircular line. The linea alba attaches to the posterior rectus sheath, thus separating the rectus abdominis muscles proximal to the semicircular line. (B) Cross-section above the semicircular line. Note that the rectus abdominis muscles are enveloped by the posterior and anterior rectus sheaths and separated from each other by the linea alba. (C) Cross section below the semicircular line. The rectus sheath exists only anteriorly. Posteriorly is the transversalis fascia and peritoneum. |

|

|

Figure 6-33 The posterior rectus sheath has been removed to reveal the peritoneum and the abdominal viscera.

|

lower half of the rectus abdominis muscle. The artery lies between the

muscle and the posterior part of the rectus sheath. If the surgical

plane remains in the midline, this vessel should escape injury. If the

artery is damaged when the rectus muscle is mobilized, it can be tied

with impunity.

ends of the aorta and the vena cava from the vertebrae in the L4-5

vertebral area. The aorta divides on the anterior surface of the L4

vertebra into the two common iliac arteries. Just below this

bifurcation, the common iliac vessels divide in turn at about the S1

level into the internal and external iliac vessels. The internal iliac

is the more medial of the two (Fig. 6-34).

anterior parts of the lower lumbar vertebrae by the lumbar vessels.

These segmental vessels must be mobilized to permit the aorta and vena

cava to be moved (see Fig. 6-13). Because the

arterial structures are easier to dissect and more muscular than are

the thin-walled venous structures, the preferred approach to the L4-5

disc space is from the left, the more arterial side. The median sacral

artery originates from the aorta at its bifurcation at L4 and runs in

the midline, over the sacral promontory and down into the hollow of the

sacrum (see Fig. 6-34). The lumbosacral disc

usually lies in the V that is formed by the two common iliac vessels.

Nevertheless, the level at which the vessels bifurcate may vary; on

rare occasions, they may have to be mobilized to expose the L5-S1 disc

space.

common iliac artery, whereas the right common iliac artery lies below

and medial to the right common iliac vein. Therefore, special care must

be taken

when

mobilizing the left side of the vascular V, because the vessel closest

to the surgery is the thin-walled vein, not the artery (Fig. 6-35; see Fig. 6-34).

|

|

Figure 6-34

The abdominal viscera has been retracted proximally, and the retroperitoneum has been resected to reveal the great vessels at their bifurcation, the ureters, and the presacral plexus. |

The nerves anterior to the L5-S1 disc are part of the superior

hypogastric plexus which receives sympathetic innervation from T11 to

L3 via the sympathetic chain and a plexus of nerves around the aorta.

Injury to these nerves may cause ejaculatory dysfunction in men

(retrograde ejaculation). More distally the plexus of nerve has

parasympathetic contributions from the pelvic nerves (S2,S3,S4) which

are important for erectile function in men. These nerves are more at

risk with surgeries anterior to the mid and lower sacrum as well as low

rectal and prostate procedures (see Figs. 6-34 and 6-35).15

|

|

Figure 6-35

Portions of the major vessels have been resected to reveal the underlying L5-S1 disc space, the sacral promontory, and its overlying presacral plexus. |

psoas muscle. At the bifurcation of the common iliac artery over the

sacroiliac joint, it clings to the posterior abdominal wall, held there

by the peritoneum, and should be well lateral to the approach to the

L5-S1 disc space. It may have to be mobilized for exposure of the L4-5

disc space (Fig. 6-36; see Fig. 6-35).

|

|

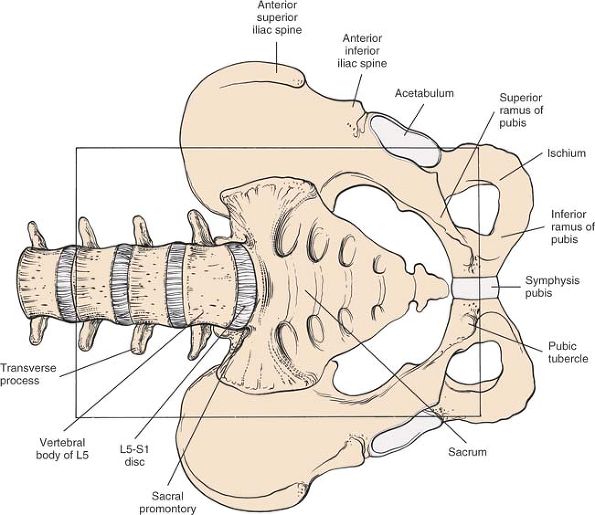

Figure 6-36 Osteology of the anterior aspect of the pelvis and lumbosacral spine.

|

lumbar spine has several advantages over the transperitoneal approach.

First, it provides access to all vertebrae from L1 to the sacrum,

whereas the transperitoneal approach is difficult to use above the

level of L4. Second, it allows drainage of an infection, such as a

psoas abscess, without the risk of a postoperative ileitis. Because of

the arrangement of the vascular anatomy of the retroperitoneal space,

however, it is slightly more difficult to reach the L5-S1 disc space

using the retroperitoneal approach.

-

Spinal fusion

-

Drainage of psoas abscess and curettage of infected vertebral body

-

Resection of all or part of a vertebral body and/or intervertebral disc and associated bone grafting

-

Biopsy of a vertebral body when a needle biopsy is either not possible or hazardous

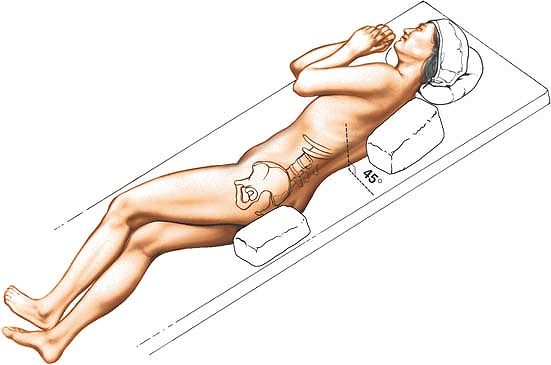

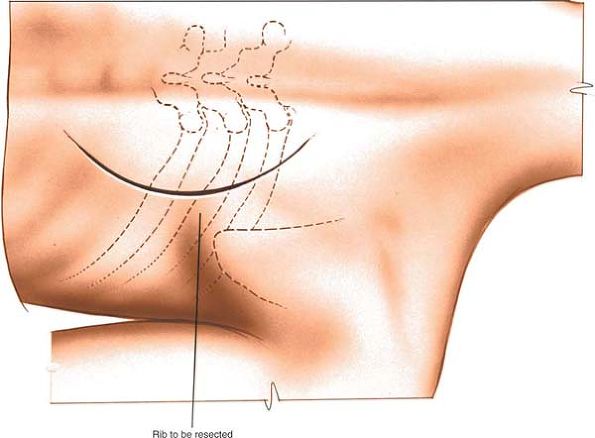

semilateral position. The patient’s body should be at about a 45° to

90° angle to the horizontal, facing away from the surgeon. Keep the

patient in this position throughout the surgery by placing sandbags

under the hips and shoulders or by using a kidney rest brace to hold

the patient. The angle allows the peritoneal contents to fall away from

the incision. Alternatively, place the patient supine on the operating

table and tilt the table at 45° to the horizontal away from the

surgeon. This position has the advantage of not putting the psoas

muscle on stretch (Fig. 6-37).

depending on whether the surgeon prefers to work on the “aortic side”

or the “caval side.”

|

|

Figure 6-37 Place the patient in the semilateral position for the anterolateral (retroperitoneal) approach to the lumbar spine.

|

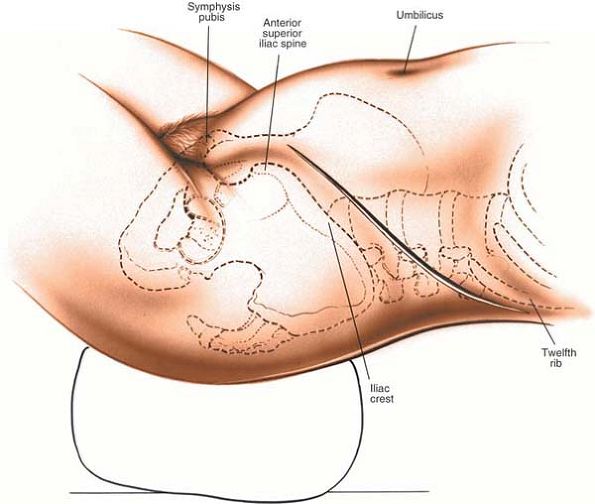

posterior half of the 12th rib toward the rectus abdominis muscle and

stopping at its lateral border, about midway between the umbilicus and

the pubic symphysis (Fig. 6-39).

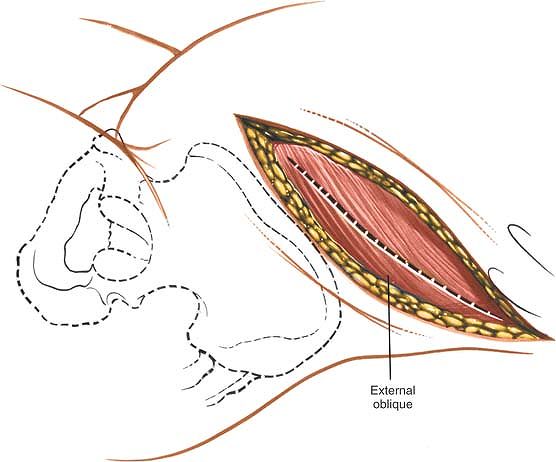

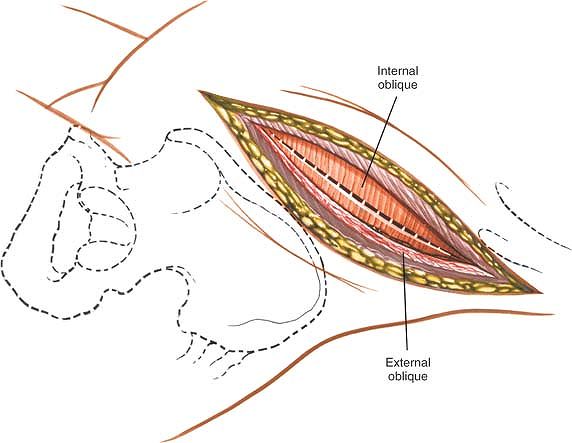

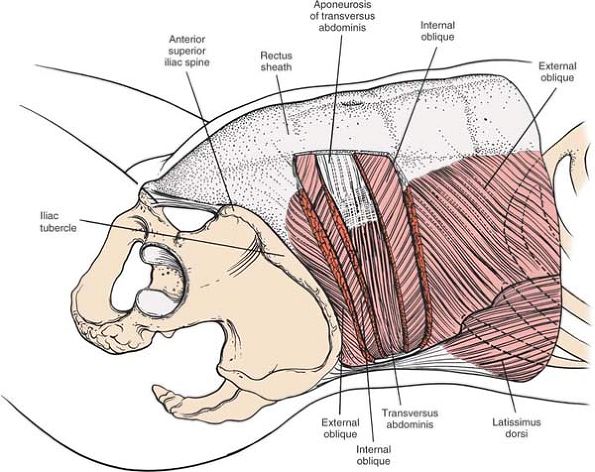

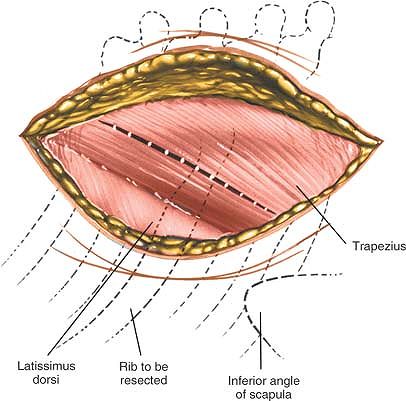

muscles of the abdominal wall (the external oblique, internal oblique,

and transversus abdominis) are divided in line with the skin incision.

Because all three muscles are innervated segmentally, significant

denervation does not occur (Fig. 6-38).

muscle. Divide the aponeurosis of this muscle in the line of its

fibers, which is in line with the skin incision. The muscle fibers of

the external oblique rarely appear below the level of the umbilicus

except in very muscular patients. If they are found there, the muscle

should be split in the line of its fibers (Fig. 6-40).

|

|

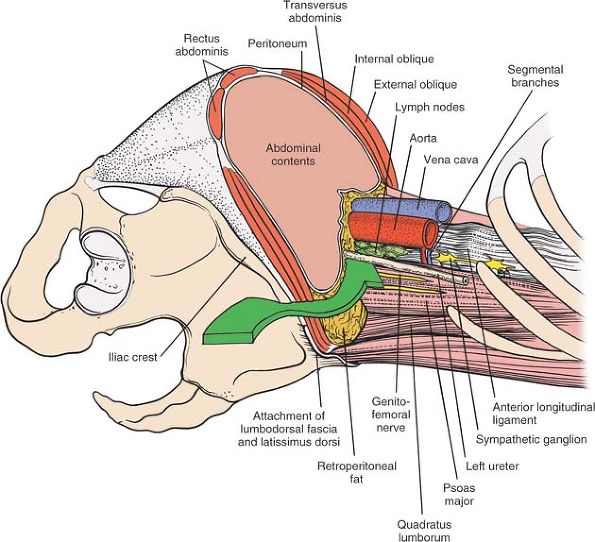

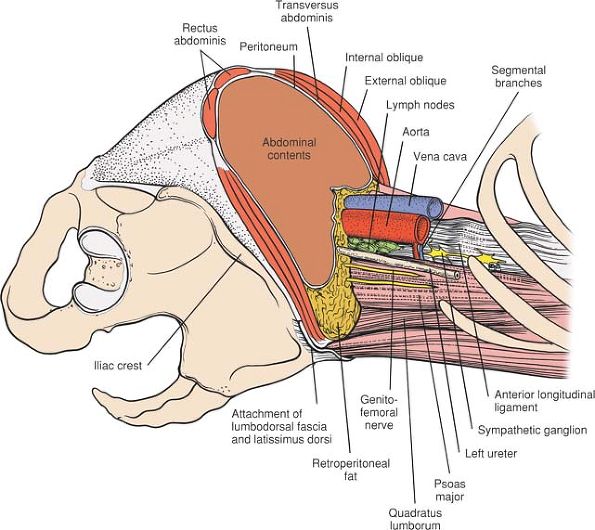

Figure 6-38 The anterior abdominal musculature and viscera have been transected and removed at the level of the iliac crest. The arrow indicates the route of surgery between the peritoneum anteriorly and the retroperitoneal structures posteriorly.

|

|

|

Figure 6-39 Make an oblique flank incision extending down from the posterior half of the 12th rib toward the rectus abdominis muscle.

|

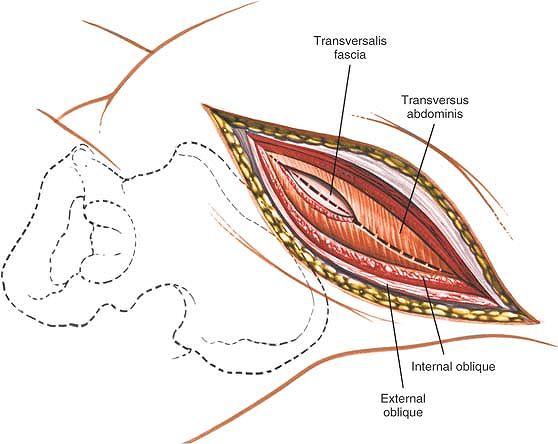

the skin incision and perpendicular to the line of its muscular fibers.

This division causes partial denervation, but if the muscle is closed

properly, postoperative hernias can be avoided (Fig. 6-41).

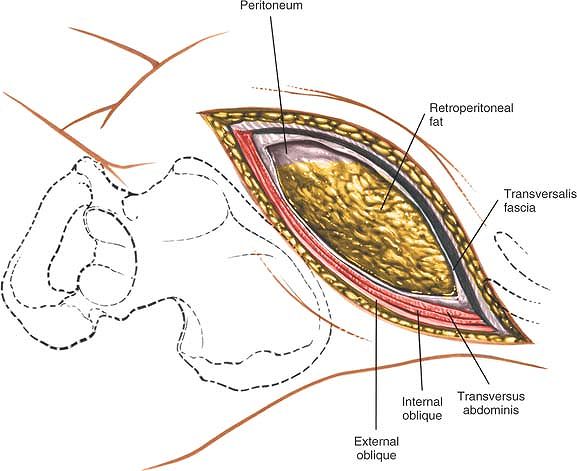

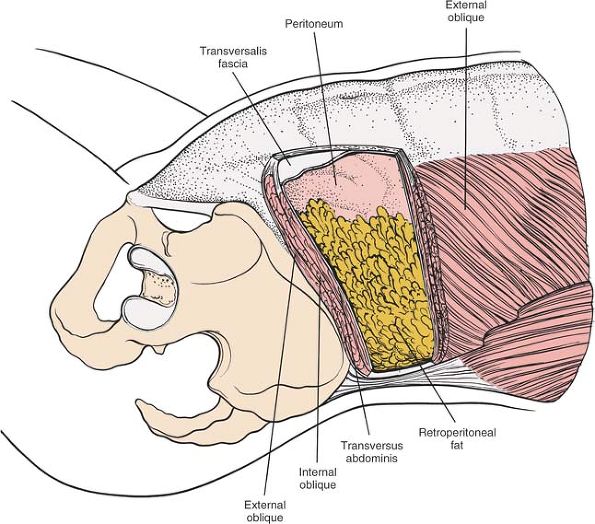

Under the internal oblique muscle lies the transversus abdominis

muscle. It, too, should be divided in line with the skin incision to

expose the retroperitoneal space (Figs. 6-42, 6-43, 6-47, and 6-48).

Carry out this dissection from either the left lower quadrant or the

right upper quadrant, depending on the side that needs to be exposed.

|

|

Figure 6-40 Incise the external oblique muscle and aponeurosis in line with its fibers and in line with the skin incision.

|

|

|

Figure 6-41 Divide the internal oblique in line with the skin incision and perpendicular to the line of its muscular fibers.

|

|

|

Figure 6-42 Divide the underlying transversus abdominis muscle in line with the skin incision.

|

|

|

Figure 6-43 In the anterior part of the wound, identify the peritoneum and its contents. Posteriorly, identify the retroperitoneal fat.

|

|

|

Figure 6-44 Using blunt finger dissection, develop the plane between the retroperitoneal fat and fascia that overlie the psoas muscle.

|

|

|

Figure 6-45 Mobilize the peritoneal cavity and its contents, and retract them medially.

|

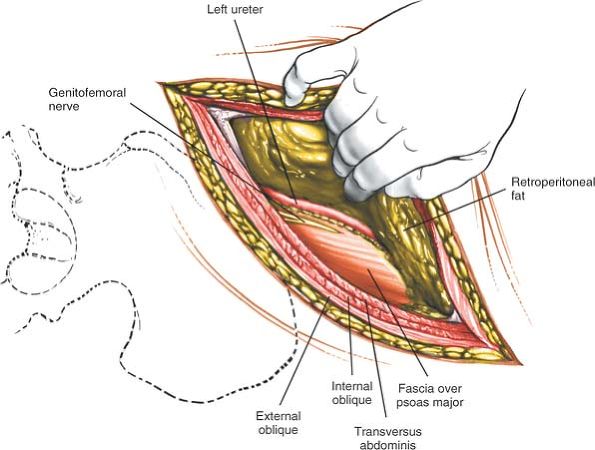

contents and retract them to the right upper quadrant. The ureter,

which is attached loosely to the peritoneum, is carried forward with it.

Any existing psoas abscess is easily palpable at this point. If one is

found, it should be entered from its lateral side with finger

dissection. Follow the abscess cavity with a finger directly to the

infected disc space or spaces. If there is no psoas abscess, follow the

surface of the psoas muscle medially to reach the anterior lateral

surface of the vertebral bodies.

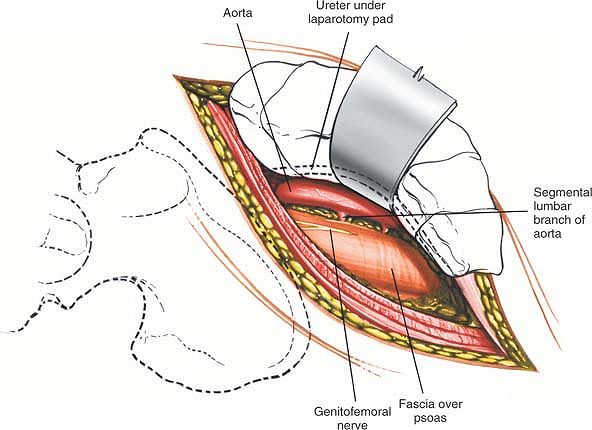

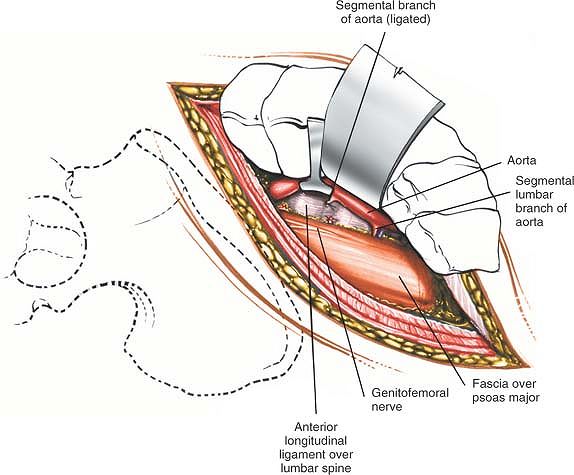

waist of the vertebral bodies by the lumbar arteries and veins. These

smaller vessels must be located individually on the involved vertebrae

and tied so that the aorta and vena cava can be mobilized and the

anterior part of the vertebral body reached. Make sure that the lumbar

vessels are not cut flush with the aorta; a slipped tie then would

prove hard to deal with (Figs. 6-46 and 6-49).

|

|

Figure 6-46

Ligate the lumbar vessels (segmental branches of the aorta). Mobilize the aorta and vena cava to reach the anterior part of the vertebral body. |

on the lateral aspect of the vertebral body and on the most medial

aspect of the psoas muscle. It is easy to identify as the tissue is

cleared from the front of the vertebrae.

on the anterior medial surface of the psoas muscle, attached to its

fascia. Easily identifiable, it should be preserved (see Figs. 6-45 and 6-49).

if the peritoneal contents are retracted vigorously when the approach

is made from the right side. The aorta will come down on, and it is a

much tougher structure that is more resistant to injury.

|

|

Figure 6-47

The external and internal oblique have been resected to reveal their relationship to each other and to the transversus abdominis muscle. |

medial aspect of the field between the peritoneum and the psoas fascia.

Because the ureter is attached not to the psoas fascia, but loosely to

the peritoneum, it normally falls forward with the peritoneum and its

contents, away from the operative field. If doubt exists regarding the

identity of the ureter, it should be stroked gently to produce

peristalsis (see Fig. 6-49).

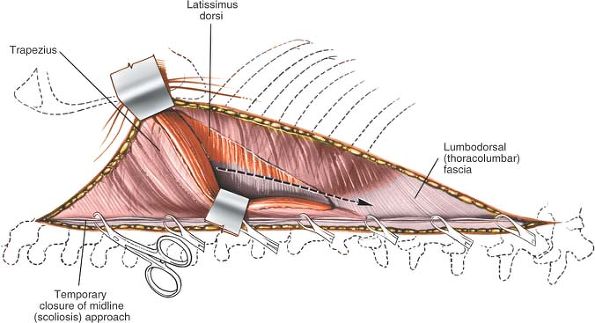

visibility. They are self-retaining and offer excellent cephalad and

caudad exposure. If the incision does not comfortably expose the

involved vertebra, continue dissecting more posteriorly, taking

additional fibers of the latissimus dorsi, and even possibly the

quadratus lumborum, to allow more posterior exposure.

vertebrae. Parallel incisions may be made at higher levels for access

to the upper lumbar vertebrae, but they involve rib resection and

potentially are hazardous because of the proximity of the pleura and

the kidney. They should be performed in conjunction with a general

surgeon unless the orthopaedic surgeon has considerable experience in

this area.

|

|

Figure 6-48 The transversus abdominis muscle is resected to reveal the peritoneum and the retroperitoneal fat.

|

|

|

Figure 6-49

The abdominal muscles and viscera have been removed proximal to the level of the iliac crest to reveal retroperitoneal structures. Note the interval between the psoas muscle and the aorta. This interval provides access to the sympathetic chain and the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies. |

approach to the cervical spine, allowing quick and safe access to the

posterior elements of the entire cervical spine. It is used for the

following:

-

Posterior cervical spine fusion16

-

Enlargement of spinal canal (laminectomy or laminoplasty)

-

Treatment of tumors

-

Treatment of facet joint dislocations17,18

-

Nerve root exploration

-

Excision of some herniated discs

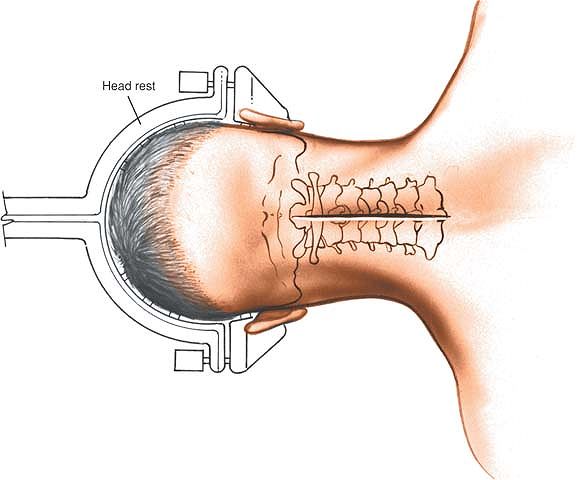

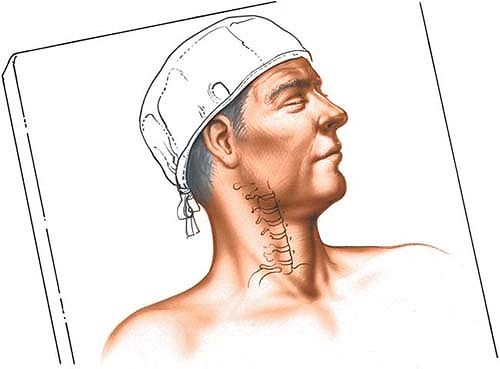

into a few degrees of flexion to open the interspinous spaces. Tongs

and a fixed brace are applied (Mayfield tongs or similar). This allows

for careful control of the head and neck position during the procedure,

minimizes the possibility of ocular pressure, and gives good access by

the anesthetist to the airway (Fig. 6-50).

has the advantage of decreasing venous bleeding, but it has been implicated as a cause of air emboli.

|

|

Figure 6-50 The position of the patient for the posterior approach to the cervical spine.

|

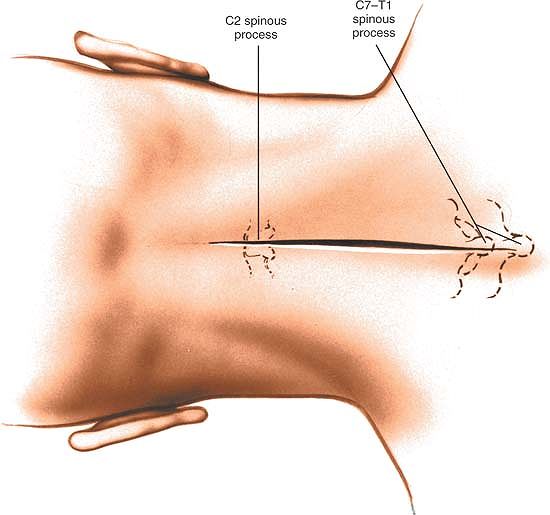

the most prominent landmarks in the vertebral arch. The C2 spinous

process is one of the largest cervical spinous processes, as are C7 and

T1. All three are quite palpable along the midline. Because it

sometimes is difficult to distinguish between C7 and T1 during surgery,

place a radiopaque marker (such as a needle) into the spinous process

at the level of the pathology before making the incision, so that the

exact location of the process can be identified. Sometimes placing a

second marker into C7 may be helpful. Because the distance between the

various cervical facet joints and interspaces is tiny, a significant

portion of the neck may be dissected unnecessarily unless the vertebra

being treated is identified, with the help of an x-ray film.

Use the needle that has been inserted into the spinous process as a

guide to and center point of the incision. Note that the skin of the

posterior cervical spine is thicker and less mobile than the skin of

the anterior neck, and that the resultant scar usually is broader;

however, hair usually covers most of the scar.

left and right paracervical muscles (which are supplied segmentally by

the left and right posterior rami of the cervical nerves).

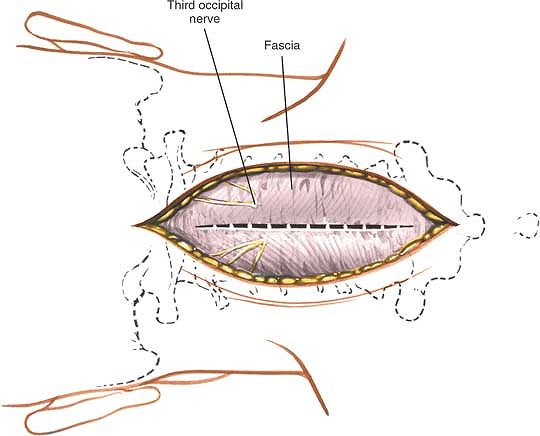

Minimal bleeding may come from venous plexuses that cross the midline;

these should be cauterized (Figs. 6-52 and 6-53).

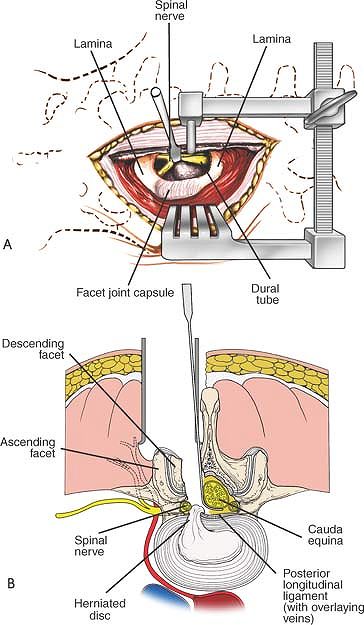

unilaterally or bilaterally, depending on the exposure needed;

bilateral removal is done for a spine fusion and unilateral removal for

a herniated disc. Use a Cobb elevator or cautery, which can remove the

muscles from the bone without damaging them unduly (Fig. 6-54). Carry the dissection as far laterally as necessary to reveal the lamina and the facet joints (Figs. 6-55 and 6-56). If necessary, cauterize the segmental arterial vessel that runs between the facets.

|

|

Figure 6-51 Make a straight incision in the midline of the neck, centering the incision over the area of pathology.

|

|

|

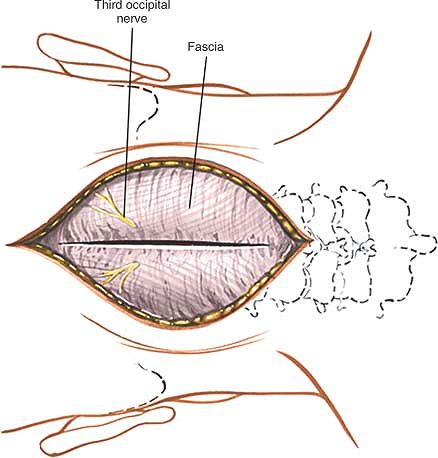

Figure 6-52 Retract the skin flaps and incise the fascia in the midline. Note the position of the third occipital nerve.

|

|

|

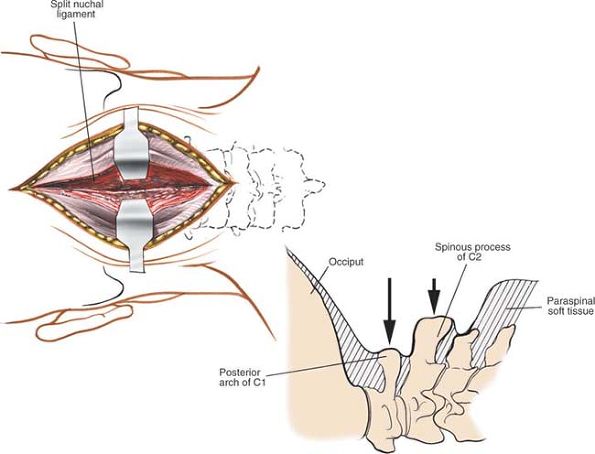

Figure 6-53 Continue the dissection down to the spinous processes through the nuchal ligament.

|

|

|

Figure 6-54

Remove the paraspinal muscles subperiosteally from the posterior aspect of the cervical spine either unilaterally or bilaterally, depending on the exposure needed. Note that the vertebral artery is considerably anterior to the posterior facet joints. |

midline and cuts into muscles, however, notable bleeding can occur that

will require immediate cauterization. If the patient has significant

spina bifida, it is possible to enter the spinal canal, injuring neural

tissue.

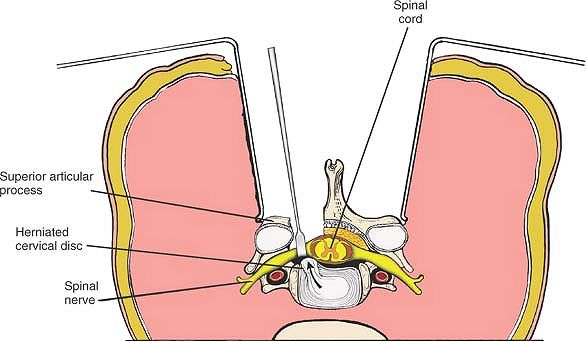

laminae. With a sharp blade, remove it from the leading edge of the

lamina of the inferior vertebra. Place a flat, spatula-shaped

instrument in the midline in the space between the two ligaments and

cut down on the ligamentum flavum, with the metallic unit separating

the ligamentum from the underlying dura. Perform a laminectomy, either

partial or complete, removing as much of the lamina as necessary to see

the blue-white dura, which lies immediately below it, probably covered

by epidural fat. Identify the posterior portion of the vertebral body,

the disc space, and the possibly herniated disc (Figs. 6-57 and 6-58).

Occasionally, the thin epidural veins surrounding the cord may bleed

significantly. The veins can bleed anywhere; they are hardest to

control between the anterior aspect of the cord and the posterior part

of the vertebral body.

|

|

Figure 6-55 Bilateral exposure of the posterior cervical spine.

|

overzealously. If enough bone is removed during the laminectomy, both

medially and laterally, the exposure should be large enough to minimize

the need for cord retraction. The nerve roots themselves should be

retracted gently to prevent unnecessary tethering from postoperative

adhesions. Occasionally, the facet joint must be removed partially to

expose the nerve root.

of the cervical nerve roots supply the paraspinal muscles and sensation

to the overlying skin; they rarely are in danger. Even if a posterior

ramus must be cauterized, the nerve supply to the paracervical muscles

and skin is so rich that the denervation has no clinical effect.

profusely. Frequently, bipolar (or Malis) cauterization is the best way to control the venous bleeding.

|

|

Figure 6-56

With a high-speed tool, then a small Kerrison rongeur, the caudal aspect of the lamina above, the rostral aspect of the lamina below, and the medial facet are removed. |

|

|

Figure 6-57

Perform a laminectomy, partial or complete, removing as much lamina as needed. Gently retract the nerve root medially to identify the posterior portion of the vertebral body. |

|

|

Figure 6-58 Identify the disc space and a possible herniated disc.

|

to the paracervical muscles may be cut or stretched as the muscles are

stripped past the facet joints. The muscles often contract, stopping

the small amount of hemorrhage; however, if the torn vessels can be

seen, they should be cauterized. The blood supply to the posterior

cervical muscles is generous. Cauterization causes no problem and

allows for a dry surgical field. Occasionally, a nutrient foramen of

the spinous processes or lamina may bleed. This can be controlled

easily with a dab of bone wax or cautery placed directly against the

foramen.

enclosed in a bony canal running through the transverse process

(transverse foramen). It is protected even if the transverse process is

dissected onto. If the process is destroyed as a result of infection,

tumor, or trauma, however, take great care not to enter the transverse

foramen (see Figs. 6-54 and 6-62).

addition, an extra vertebra may have to be dissected out proximally or

distally. The exposure may be expanded laterally by drawing the muscles

well out and past the facet joints and onto the transverse processes

without causing damage, except at C1 and C2. On occasion, the laminae

even may be exposed bilaterally and the laminectomy extended both

proximally and distally to improve exposure to the spinal cord and

nerve roots.

be extended proximally (staying in the midline plane) as high as the

occiput of the skull and as far distally as the coccyx via

subperiosteal removal of the paraspinal muscles.

cervical spine run longitudinally and are supplied segmentally.

Although it is not critical to know the various individual posterior

muscles of the cervical spine, being aware of these muscles and their

layers is helpful. Because the approach itself is in the midline, it

disturbs no vital structures and is relatively safe.

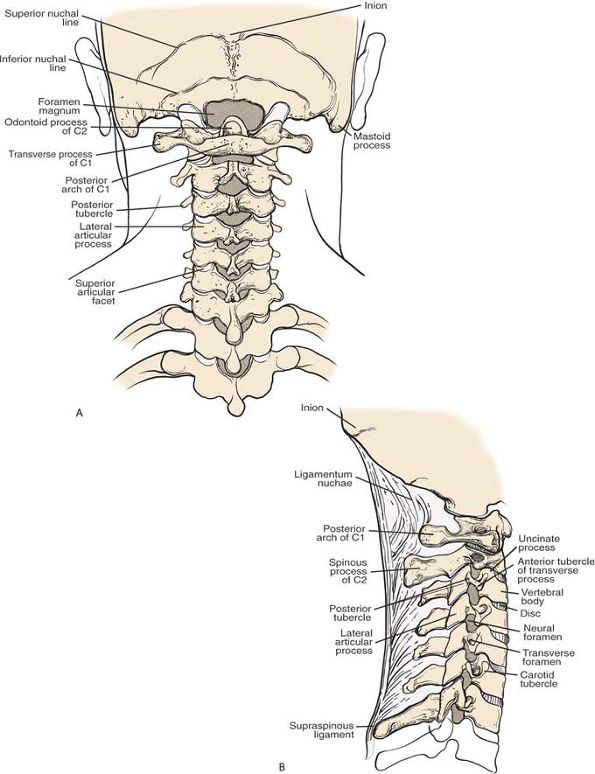

C6, are bifid. C2 is the largest proximal cervical spinous process; the

spinous processes of C3, C4, and C5 are relatively small. C7 is

thicker, is not bifid, and has a tubercle at its end. Because it is the

largest distal cervical spinous process, it is easy to palpate (see Fig. 6-63A).

caudad and posteriorly, serving as points of attachment for the

cervical muscles.

mobile than is the skin on the throat; it is attached directly to the

underlying fascia. The incision runs perpendicular to the tension line

of the skin, causing thicker scarring. Nevertheless, the wound usually

heals well, and, because the nape of the neck is covered with hair,

cosmetic concerns seldom are a problem.

takes origin from the occiput and inserts into the C7 spinous

processes, sending septa down to each of the cervical spinous processes

and dividing the more lateral paracervical muscles. The septum, which

is almost vestigial in humans, is well developed in quadrupeds, because

it helps the muscles support the head. It is the homologue of the

supraspinous ligament in the rest of the spine. Dissection through it

is safe, as long as it remains in the midline (see Fig. 6-63B).

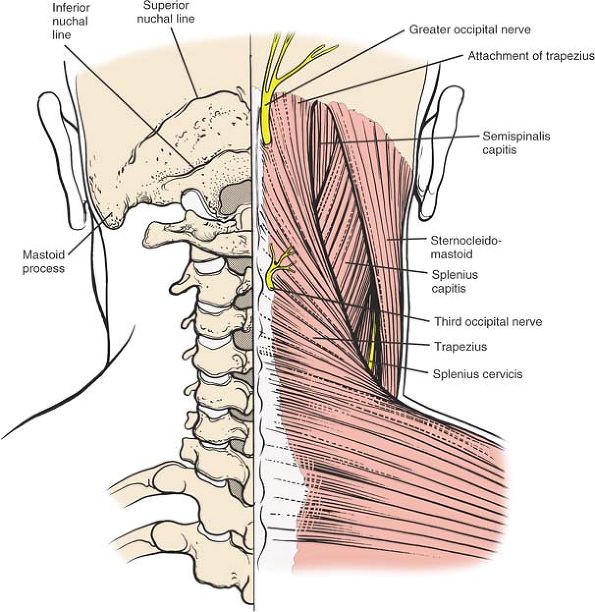

consists of the trapezius muscle, which takes origin from the superior

nuchal line and from all the spinous processes of the cervical spine.

The trapezius covers the entire cervical area; in common with its

counterpart in the lumbar spine, the latissimus dorsi, it is

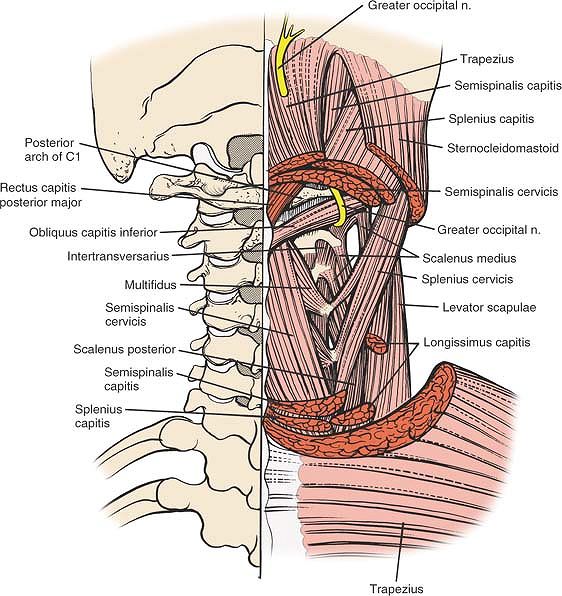

essentially an upper limb muscle (Fig. 6-59).

filled by the splenius capitis, a relatively large, flat muscle that

takes origin from the midline (spine of C7, the lower half of the

ligamentum nuchae, and the upper three thoracic spinous processes) and

inserts into the occipital bone (Fig. 6-60).

|

|

Figure 6-59

The superficial musculature of the cervical spine consists of the trapezius and the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Between these and deeper levels lies the intermediate layer, the splenius capitis. |

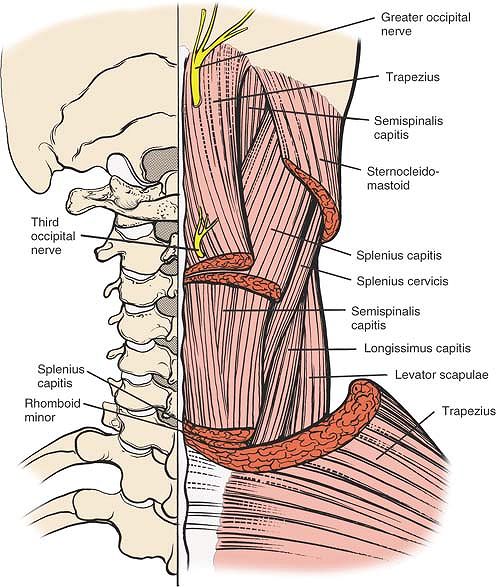

into three portions: superficial, middle, and deep. The superficial

portion consists of the semispinalis capitis, a relatively large muscle

that lies immediately beneath the splenius. The semispinalis capitis

takes its origin from the transverse processes of the cervical

vertebrae and inserts into the occipital bone. The middle portion of

the deep layer is filled by the semispinalis cervicis, which originates

from the transverse processes of the upper five or six thoracic

vertebrae

and

inserts into the midline interspinous processes. The deepest portion of

the deep layer consists of the multifidus muscles and the short and

long rotator muscles (Fig. 6-61).

|

|

Figure 6-60

The superficial layer has been resected to reveal the splenius capitis, which also is resected partially. Deep to this are the semispinalis capitis, the longissimus capitis, the splenius cervicis, and, most laterally, the levator scapulae. |

medial to lateral at 45°. Lateral to the laminae are the joint

capsules, which completely surround the cervical facet joints. The

facet joints are in a frontal plane (Figs. 6-63B and 6-64).

canal is safe during this phase of the dissection. A wide, flat

instrument (such as a Cobb dissector) held transverse to the lamina

helps to protect the canal (see Fig. 6-54).

connects the lamina on one vertebra to the adjacent vertebra, filling

the space between the two. The ligaments are paired, one on each side,

and may be separated in the midline by a tiny space. They take origin

from the leading edge of the lower lamina and insert proximally into

small ridges on the anterior surface of the higher vertebra, about one

third up the anterior surface.

beneath the ligamentum flavum. Therefore, the ligament must be removed

carefully, so that the coverings of the cord (the outer dura, the

middle arachnoid, the inner pia) do not tear.

|

|

Figure 6-61 The semispinalis capitis has been resected to reveal the deepest layer, the semispinalis cervicis, and the multifidi muscles.

|

posterior surface of the cervical vertebral bodies, within the

vertebral canal, and extends down through the entire spinal canal. The

ligament attaches to each vertebra and disc; it is broadest in the

cervical region. Over the ligament, on the floor of the canal, lie

large vertebral veins, comprising a nonvalvular venous plexus. These

may bleed and require cauterization.

vertebral artery. The artery runs upward in the neck through a series

of foramina in the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae.

Vigorous decortication may breach the posterior walls of these foramina

and damage the artery, which carries a blood supply that is vital to

the hindbrain. The risks are far greater when the transverse processes

are involved in pathology. If the artery is damaged during dissection,

it should be packed to produce at least temporary control of bleeding.

In most situations, this will also produce definitive control;

occasionally, repair of the artery or legatum will be required (see Figs. 6-62 and 6-64).

|

|

Figure 6-62

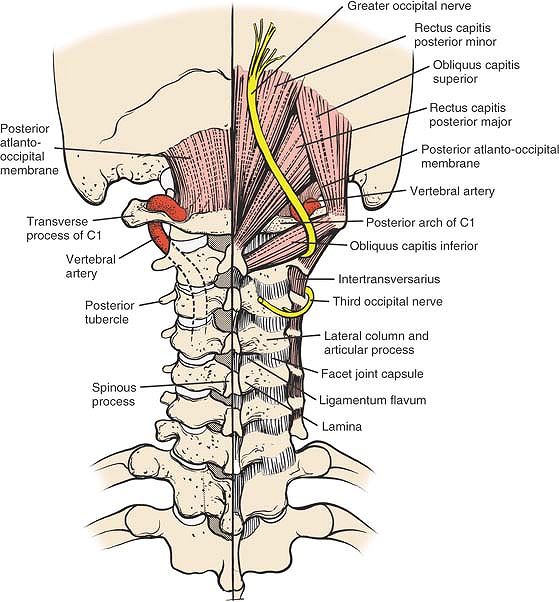

The muscles of the posterior triangle of the neck consist of the rectus capitis posterior minor and major, and the obliquus capitis superior and inferior. Note the course of the vertebral artery on the superior border of the arch of C1. It is lateral to the midline. The course of the vertebral artery in the transverse foramen distal to C1 is anterior to the facet joints. Rectus Capitis Posterior Major. Origin. Tendinous, from spinous process of axis. Insertion. Into lateral part of inferior nuchal line of occipital bone and immediately below this line. Action. Extends head and rotates it to same side. Nerve supply. Nerve branch of posterior primary rami main line of suboccipital nerve.

Rectus Capitis Posterior Minor. Origin. Tendinous, from tubercle of posterior arch of atlas. Insertion.

Into medial part of nuchal line of occipital bone and surface beneath it, and foramen magnum (only muscle to take origin from posterior arch of C1). Action. Extends head. Nerve supply. A branch of posterior primary main line of suboccipital nerve. Obliquus Capitis Inferior. Origin. From apex of spinous process of axis. Insertion. Into inferoposterior part of transverse process of atlas. Action. Rotates atlas; turns head toward same side. Nerve supply. Branches of posterior primary rami main line of greater occipital nerve.

Obliquus Capitis Superior. Origin. From tendinous fibers from upper surface of transverse process of atlas. Insertion. Into occipital bone between superior inferior nuchal lines; lateral to the semispinalis capitis. Action. Extends head and bends it laterally. Nerve supply. A branch of posterior primary division of greater occipital nerve (first cervical nerve).

|

|

|

Figure 6-63 Osteology of the cervical spine in posterior (A) and lateral (B) views.

|

|

|

Figure 6-64 Cross-section of the cervical spine. Note that the vertebral artery is anterior to the nerve root.

|

vertebrae C1 and C2, the atlas and the axis, is similar to that for the

rest of the cervical spine. Because the two vertebrae differ slightly

in their anatomy and function, however, they are discussed separately.

The uses for this approach are the following:

-

Spinal fusion19

-

Decompression laminectomy

-

Treatment of tumors

is the largest spinous process in the proximal part of the cervical

spine, it is hard to palpate except as a resistance. C1 has no spinous

process at all and is not palpable.

|

|

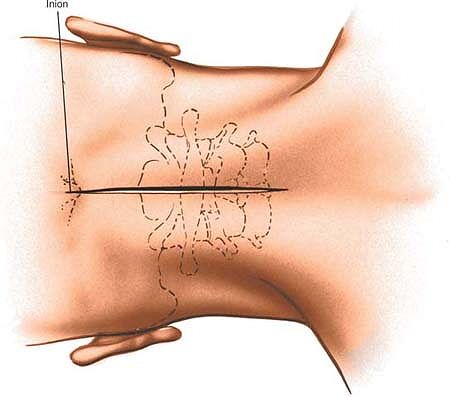

Figure 6-65 Make an incision in the midline from the external occipital protuberance inferiorly for 6 to 10 cm.

|

supplied by branches of the left and right posterior primary rami of

the proximal cervical nerve roots. The plane is internervous and

extensile.

incising the fascia and nuchal ligament in the midline of the neck,

cutting down onto the large spinous process of C2 (Figs. 6-60 and 6-67).

Extend this fascial incision distally onto the spinous process of C3

and then proximally onto the tubercle of C1. Continue proximally,

cutting down onto the external occipital protuberance.

Use a wide dissecting instrument (such as a Cobb elevator) to avoid

inadvertently breaching the spinal canal. Note that the facet joints

between C1 and C2 are about an inch further anterior than are those

between C2 and C3. Carry the dissection up to the base of the occiput,

if necessary, to expose the superior margin of the ring of C1 (see Fig. 6-68).

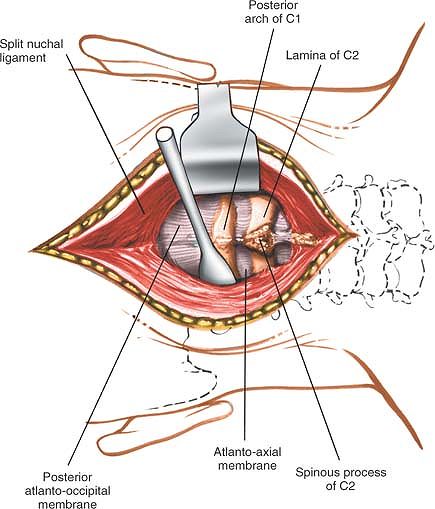

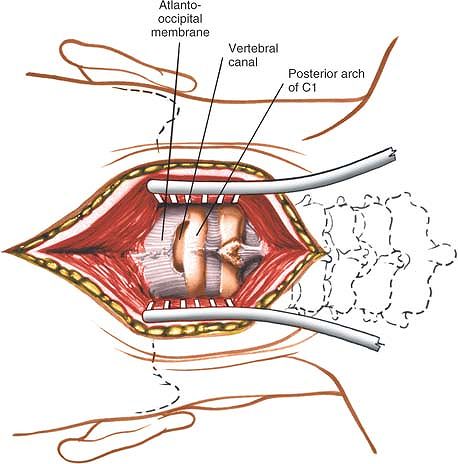

atlantoaxial ligament) can be removed from between C2 and C1, and the

posterior atlantooccipital membrane can be removed from between C1 and

the occiput (Fig. 6-69). This rarely is

necessary. Usually, separating these membranes from bone is all that is

needed to pass a wire underneath the arch of C1 so that the area can

retain bone graft. Once these posterior ligaments have been removed,

the dura of the cervical portion of the spinal cord is uncovered.

|

|

Figure 6-66 Deepen the wound in line with the skin incision by incising the fascia and nuchal ligament in the midline of the neck.

|

between the dura and the bony ring at the level of C1-2, and the cord

rarely has to be retracted. Retracting the cord is extremely hazardous,

because overzealous retraction can cause death from respiratory

paralysis; in principle, it simply should not be retracted.

These nerves, which are branches from the posterior rami, supply a

large area of skin at the back of the scalp. They run upward from a

lateral position, and midline dissection does not damage them. Take

care when dissecting laterally to stay on bone and avoid damaging these

nerves.

the operative field. It passes from the transverse foramen of the

atlas, immediately behind the atlanto-occipital joint, and pierces the

lateral angle of the posterior atlantooccipital membrane. It is

vulnerable at that point during the approach (see Fig. 6-62).

paracervical muscles from their attachments to the skull. Extend the

incision distally and strip the muscles off the posterior bony elements

of C3.

approach to the spinous processes of the remaining cervical vertebrae.

Theoretically, the approach can be extended down to the coccyx.

|

|

Figure 6-67 Incise the nuchal ligament down onto the large spinous processes of C2. Lateral view (inset). Note that the ring of C1 is further anterior than the spinous process of C2.

|

|

|

Figure 6-68 Remove the paracervical muscles from the posterior elements of C1 and C2. Carry the dissection up to the base of the occiput.

|

|

|

Figure 6-69 Remove the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane from between C1 and the occiput, if necessary.

|

of the upper cervical spine. As in other parts of the spine, the

muscles covering C1 and C2 lie in three layers. The outer layer

consists of the trapezius, a muscle of the upper limb. The intermediate

layer is made up of the paraspinal muscles, in this case, the splenius

capitis and the semispinalis capitis.

there are four pairs of small muscles that drive the unusual movements

that these joints are capable of. The riskiest part of surgery in the

area occurs in the deepest plane. The vertebral artery, which runs

through the foramen transversarium (still deeper) never should be seen

during dissection, but its position always must be kept in mind.

accommodating the insertions of the semispinalis cervicis and

multifidus, deep muscles that attach to it and stop, leaving the atlas

with almost no muscle attachment so that it is free to rotate around

the occiput. The posterior vertebral arch of C2 and its lamina, which

ascends to the spinous processes, are massive enough to support the

larger spinous process.

or inion, a large boss of bone in the center of the occiput, divides

the superior nuchal line, which extends from it to each side. The

superior nuchal line separates the scalp above from the area of

insertion of the nuchal muscles (see Fig. 6-63).

blood supply. Because the incisions run along the midline, they suffer

minimal tension. Cosmetically, they are difficult to see because of the

hairline.

extends from the external occipital protuberance to the spinous process

of the seventh cervical vertebra. A septum extends from its anterior

border; it attaches to the posterior tubercle of the atlas and all the

remaining spinous processes of the cervical spine (see Fig. 6-63B).

consist of the trapezius (in the superficial layer) and the splenius

capitis, which covers the semispinalis capitis and the longissimus

capitis (all in the intermediate layer; see Figs. 6-59 and 6-60).

processes before inserting into the base of the skull. Deep to it lies

the semispinalis cervicis, which inserts onto the axis.

of the suboccipital triangle, the rectus capitis posterior major and

minor, and the oblique capitis inferior and superior (see Fig. 6-62).

form the remaining posterior coverings of the cord, are homologues of

the original ligamentum flavum. The spinal canal at C1-2 is

particularly spacious, allowing extensive motion.

aspect of the suboccipital triangle: the greater occipital nerve (the

posterior primary ramus of C2) and the third occipital nerve (the

posterior primary ramus of C3; see Figs. 6-59 and 6-62). The most important structure in the suboccipital triangle is the vertebral artery.

This key blood supply to the hindbrain ascends in the neck through a

series of foramina in the transverse processes. At the level of the

atlas, it pierces the foramen transversarium of the atlas and then

turns medially behind the atlantooccipital joint. To enter the spinal

canal, it pierces the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane at its

lateral angle; therefore, it is extremely vulnerable during dissection

of the atlanto-occipital membrane (see Fig. 6-62).

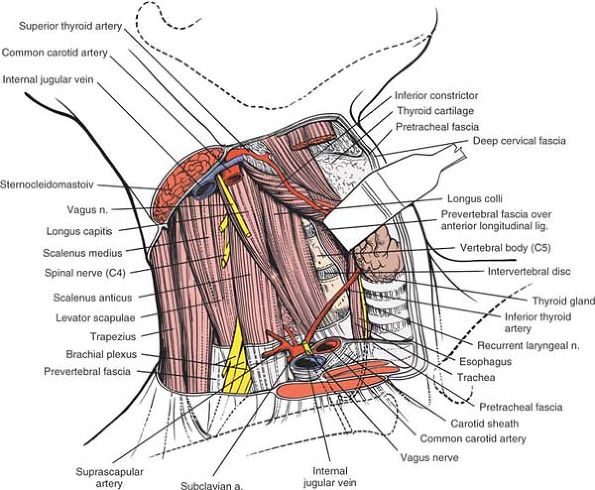

anterior vertebral bodies from C3 to T1. It also allows direct access

to the disc spaces and uncinate processes in the region. It is used for

the following:

-

Excision of herniated discs (R.B. Cloward, personal communication, 1969)20

-

Interbody fusion (see the section regarding the anterior approach to the iliac crest for bone graft)

-

Removal of osteophytes from the uncinate processes and from either the anterior or the posterior lip of the vertebral bodies

-

Excision of tumors and associated bone grafting

-

Treatment of osteomyelitis

-

Biopsy of vertebral bodies and disc spaces

-

Drainage of abscesses

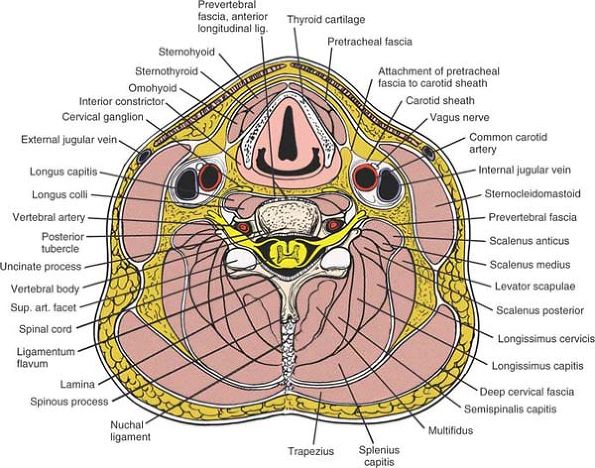

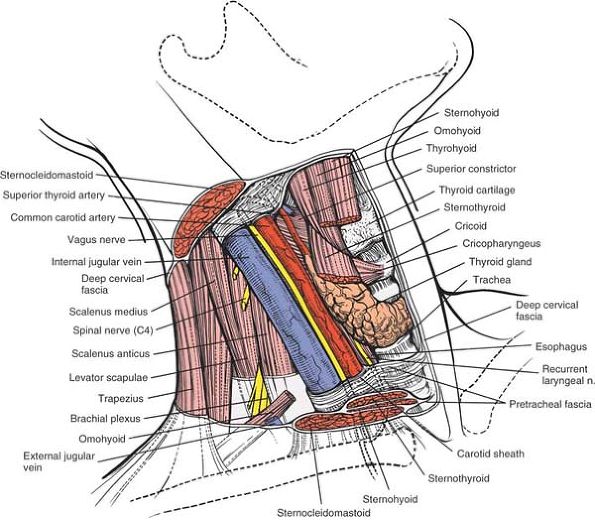

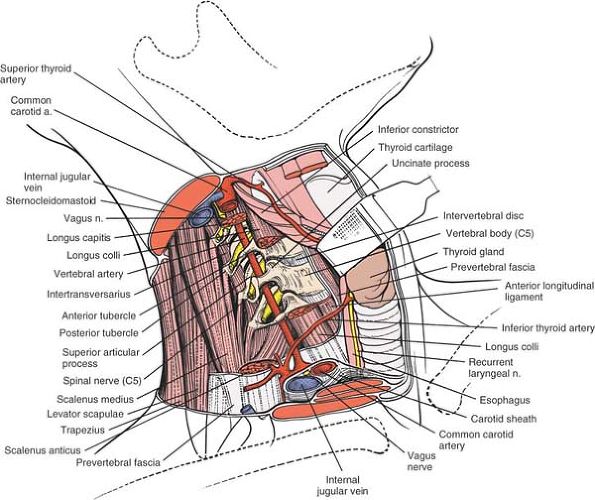

structure at risk during the anterior approach to the cervical spine.

The left recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends in the neck between the

trachea and the esophagus, having branched off from its parent nerve,

the vagus, at the level of the arch of the aorta. The right recurrent

laryngeal nerve runs alongside the trachea in the neck after hooking

around the right subclavian artery. In the lower part of the neck, it

crosses from lateral to medial to reach the midline trachea; therefore,

it is slightly more vulnerable during the exposure than is the left

recurrent laryngeal nerve. This is why some surgeons prefer left-sided

approaches, whereas others simply approach from the side of pathology.

|

|

Figure 6-70

Place the patient supine on the operating table with a small sandbag between the shoulder blades to ensure an extended position of the neck. Turn the patient’s head away from the planned incision. |

small sandbag or roll between the shoulder blades to ensure extension

of the neck. Turn the patient’s head away from the planned incision to

provide good access to the side of the neck (Fig. 6-70).

Some cases may require application of halter traction so that it can be

used later if distraction is required. Elevate the table 30° to reduce

venous bleeding and make the neck more accessible. Place the patient’s

arm at his or her side after careful padding.

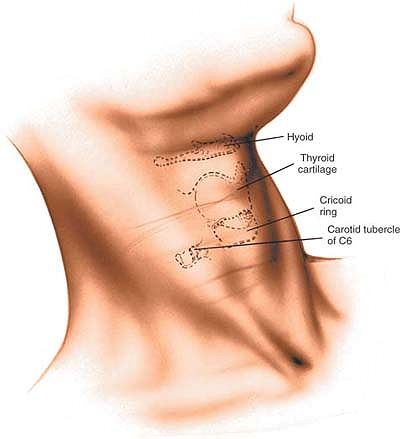

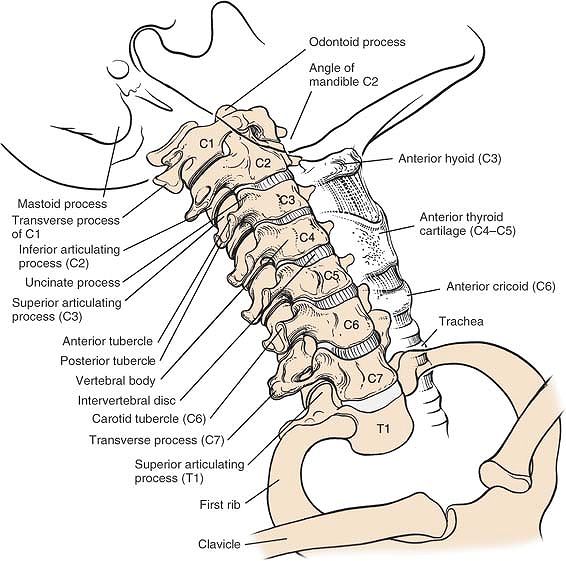

-

Hard palate–arch of the atlas

-

Lower border of the mandible–C2-3

-

Hyoid bone–C3

-

Thyroid cartilage–C4-5

-

Cricoid cartilage–C6

-

Carotid tubercle–C6

The sternocleidomastoid, an oblique muscle, runs from the mastoid

process to the sternum, just lateral to the midline of the neck. To

make it more prominent, turn the head away from the muscle in question,

into the operating position.

|

|

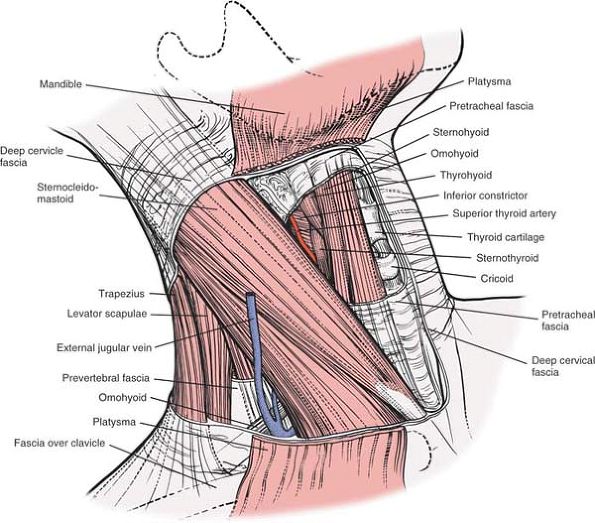

Figure 6-71 Make an oblique incision in the skin crease of the neck at the appropriate level of the vertebral pathology.

|

transverse skin crease incision at the appropriate level of the

vertebral pathology (see above). The incision should extend obliquely

from the midline to the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid

muscle. Such an incision has extreme cosmetic advantage (see Fig. 6-71).

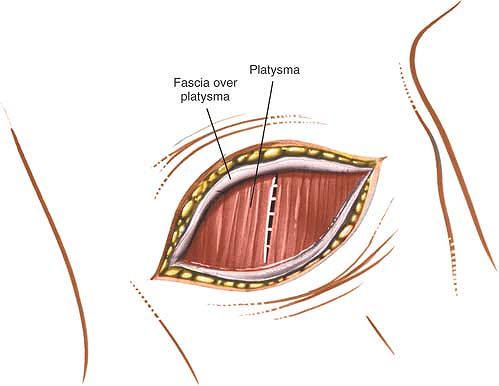

incising or dividing the platysma muscle causes no significant

problems; the muscle is supplied high up in the neck by branches of the

facial (seventh cranial) nerve.

sternocleidomastoid muscle (which is supplied by the spinal accessory

nerve) and the strap muscles of the neck

(which receive segmental innervation from C1, C2, and C3; see Fig. 6-74, cross section).

|

|

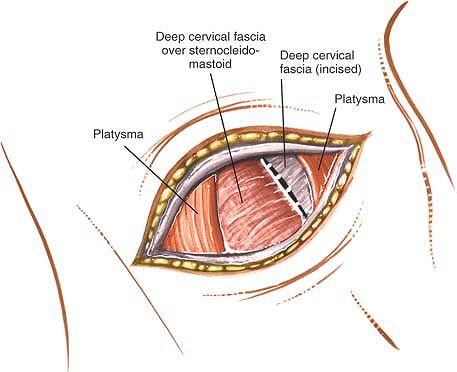

Figure 6-72

Incise the fascial sheath over the platysma in line with the skin incision. Split the platysma longitudinally, parallel to its long fibers. |

longus colli muscles, which are supplied separately by segmental

branches from the second to the seventh cervical nerves (see Fig. 6-76, cross section).

this reason, some surgeons inject the area with a dilute solution of

epinephrine (Adrenalin) before incising the skin.

|

|

Figure 6-73 Identify the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid and incise the fascia medially anterior to it.

|

Then, split the platysma longitudinally using the tips of the index

fingers, dissecting parallel to the long fibers. The platysma fibers

can also be divided with a knife. Identify the anterior border of the

sternocleidomastoid muscle and incise the fascia immediately anterior

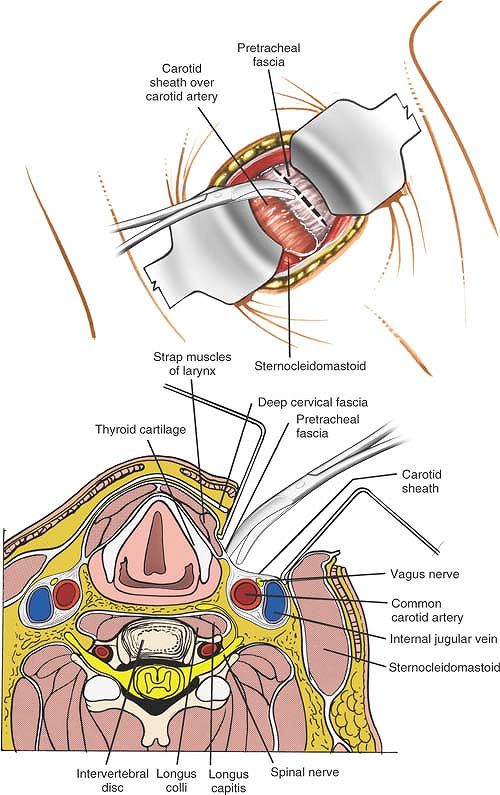

to it (Fig. 6-73). Using the fingers, gently retract the sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally. Retract the sternohyoid

and sternothyroid strap muscles (with the associated trachea and underlying esophagus) medially.

edge of the carotid sheath and the midline structures (thyroid gland,

trachea, and esophagus), cutting through the pretracheal fascia on the

medial side of the carotid sheath. Retract the sheath and its enclosed

structures laterally with the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 6-75).

|

|

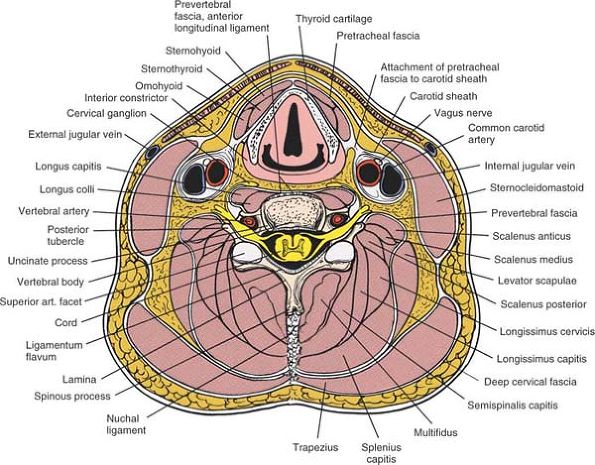

Figure 6-74

Retract the sternocleidomastoid laterally, and the strap muscles and thyroid structures medially. Cut through the exposed pretracheal fascia on the medial side of the carotid sheath. The cervical spine C3 through C5 (cross-section). Retract the sternocleidomastoid laterally and the strap muscles medially, and incise the pretracheal fascia immediately medial to the carotid sheath. |

and inferior thyroid arteries, may limit the extent to which this plane

can be opened up above C3-4. Occasionally, either or both of them may

have to be ligated and divided to open the plane.

|

|

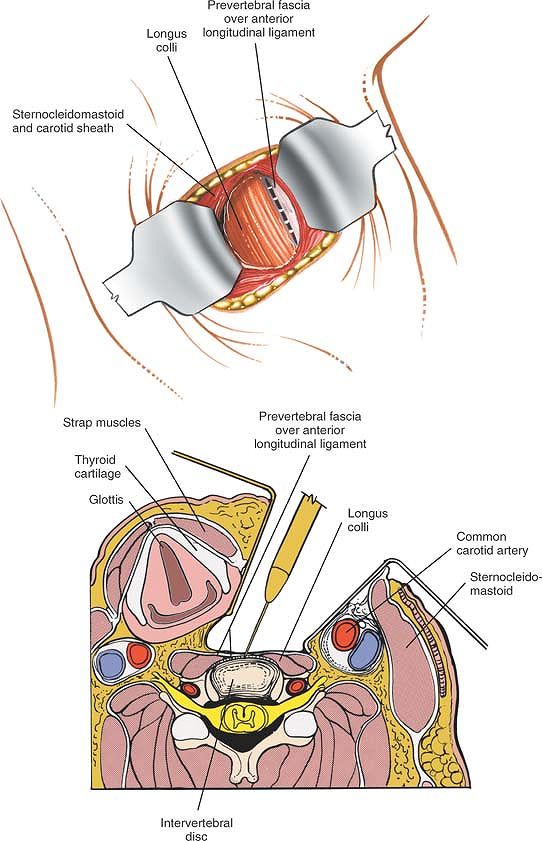

Figure 6-75

Retract the sternocleidomastoid and the carotid sheath laterally, and the strap muscles, trachea, and esophagus medially to expose the longus colli muscle and pretracheal fascia. Retract the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carotid sheath laterally, and the strap muscles and thyroid structures medially, then split the longus colli muscle longitudinally in the midline (cross-section). |

|

|

Figure 6-76

Dissect the longus colli muscle subperiosteally from the anterior portion of the vertebral body and retract each portion laterally to expose the anterior surface of the vertebral body. The longus colli muscles are retracted to the left and right of the midline to expose the anterior surface of the vertebral body (cross-section). |

by blunt dissection, proceeding carefully in a medial direction behind

the esophagus, which is retracted from the midline.

the longus colli muscle and the prevertebral fascia. The anterior

longitudinal ligament in the midline can be seen as a gleaming white

structure. The sympathetic chain lies on the longus colli, just lateral

to the vertebral bodies (see Fig. 6-75).

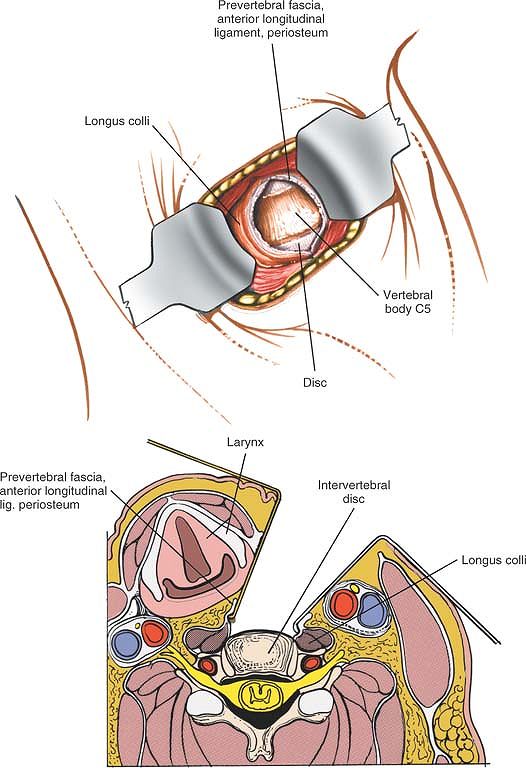

longitudinally over the midline of the vertebral bodies that need to be

exposed (see Fig. 6-75, cross section).

Then, dissect the muscle subperiosteally with the anterior longitudinal

ligament and retract each portion laterally (i.e., to the left and

right of the midline) to expose the anterior surface of the vertebral

body (Fig. 6-76).

Obtain a lateral radiograph after placing a needle marker in the

appropriate vertebral body to identify the level correctly. Make sure

that the retractors are placed underneath each of the longus colli

muscles, widening the exposure while protecting the recurrent laryngeal

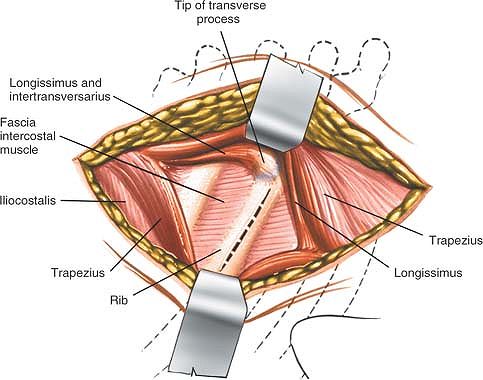

nerve, trachea, and esophagus.