The Wrist and Hand

this chapter: three to the wrist and two each to the flexor tendons and

scaphoid.

is used primarily for exploring the carpal tunnel and its enclosed

structures. The applied anatomy of each approach is considered

separately in this chapter.

is useful in the treatment of phalangeal fractures. A discussion of the

applied anatomy of the finger flexor tendons follows the description of

these two approaches in this chapter.

The methods of drainage used for these conditions are described

together, with an introduction to the general principles of drainage in

the hand. Of all the infections of the hand that require surgery,

paronychia and felons are by far the most common.

surgical approaches. In the hand, however, the majority of wounds

encountered arise from trauma, not from planned incisions. A brief

review of the overall anatomy of the hand is vital to explain the

damage that may be caused by a particular injury. Although clinical

findings are the key to the accurate diagnosis of tissue trauma,

knowledge of the underlying anatomy is crucial in bringing to light all

possibilities and minimizing the risk that a significant injury will be

overlooked. For example, arterial hemorrhage from a digital artery in a

finger nearly always is associated with damage to a digital nerve,

because the nerve lies volar to the severed artery. Arterial hemorrhage

in a finger should alert the surgeon to the possibility of nerve

injury, which often appears clinically as a change in the quality of

sensation rather than as complete anesthesia, and can be overlooked in

a brief examination.

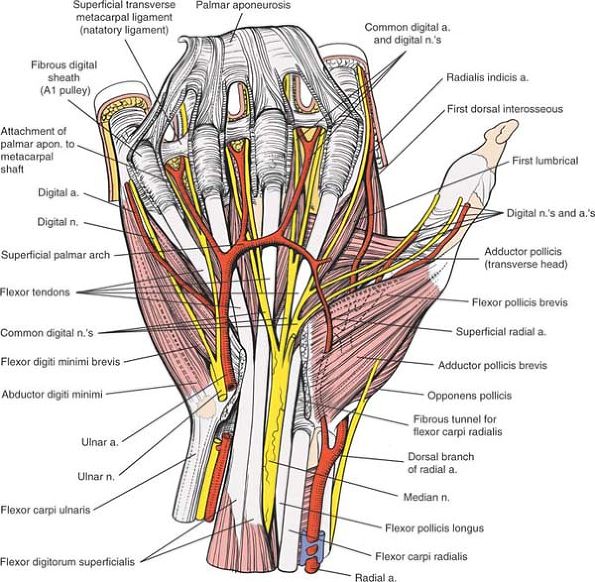

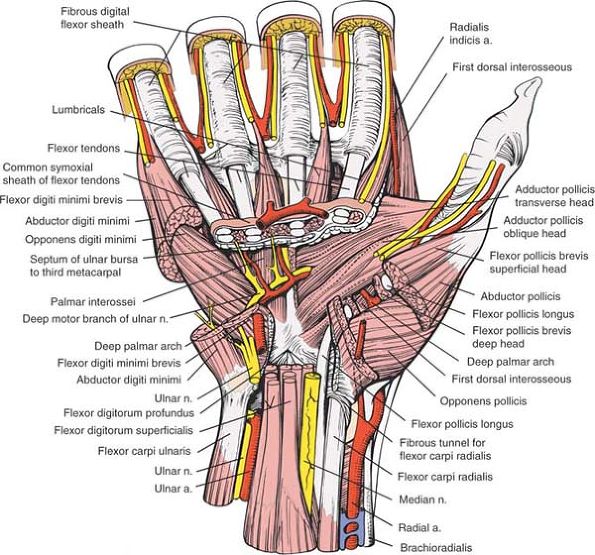

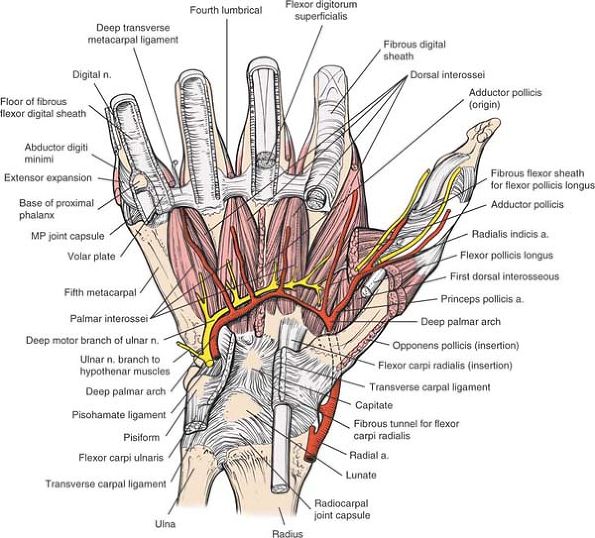

topographic anatomy of the hand. This information is presented in one

section rather than on an approach-by-approach basis to provide a clear

and integrated picture of hand anatomy.

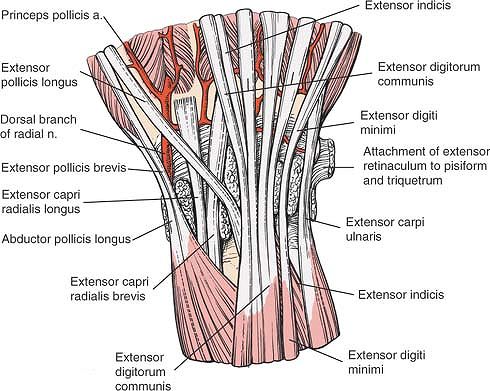

the extensor tendons that pass over the dorsal surface of the wrist. It

also allows access to the dorsal aspect of the wrist itself, the dorsal

aspect of the carpus, and the dorsal surface of the proximal ends of

the middle metacarpals. Its uses include the following:

-

Synovectomy and repair of the extensor tendons in cases of rheumatoid arthritis; dorsal stabilization of the wrist1,2

-

Wrist fusion3

-

Excision of the lower end of the radius for benign or malignant tumors

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

certain distal radial and carpal fractures and dislocations, including

dorsal metacarpal dislocations, displaced intraarticular dorsal lip

fractures of the radius, and transscaphoid perilunate dislocations.

Plates applied to the dorsal surface of the distal radius frequently

cause irritation to the numerous extensor tendons that pass over their

surface. For this reason, volar approaches are now usually preferred

for plate fixation of fractures of the distal radius. Volar approaches

are particularly suitable for locked internal fixators. -

Proximal row carpectomy4,5

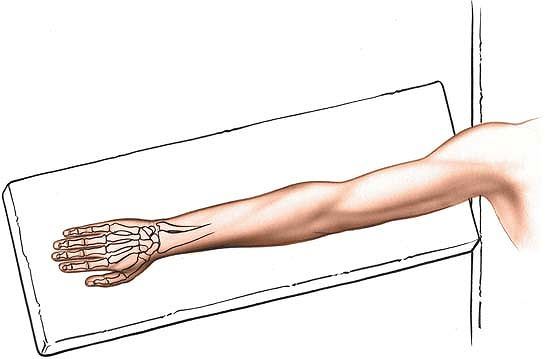

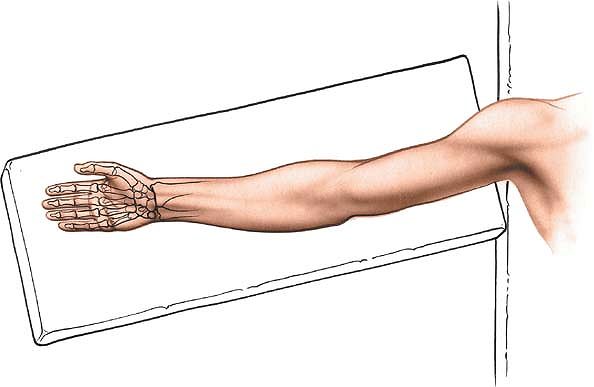

the forearm and put the arm on an arm board. Exsanguinate the limb by

applying a soft rubber bandage, and then inflate a tourniquet (Fig. 5-1).

|

|

Figure 5-1

Place the patient supine on the operating table. Turn the forearm downward and place the arm on a board, for the dorsal approach to the wrist joint. |

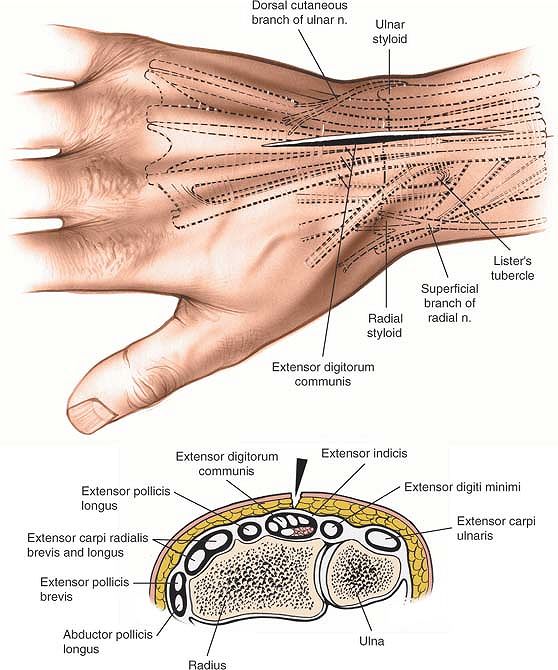

of the wrist, crossing the wrist joint midway between the radial and

ulnar styloids. The incision begins 3 cm proximal to the wrist joint

and ends about 5 cm distal to it. It can be lengthened if necessary (Fig. 5-2).

and redundant, the incision does not cause a contracture of the wrist

joint, even though it crosses a major skin crease at right angles.

extensor carpi radialis longus muscle and the extensor carpi radialis

brevis muscle are supplied by the radial nerve. Because both muscles

receive their nerve supply well proximal to the incision, however, the

intermuscular plane between them can be used safely.

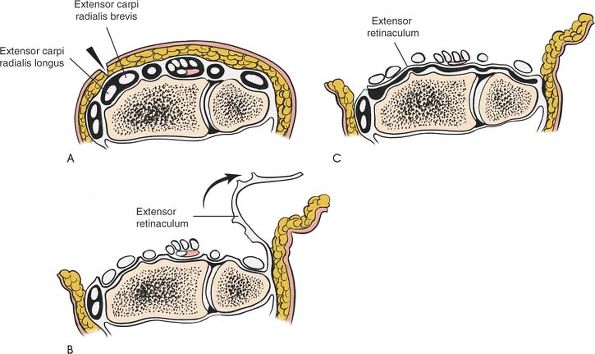

incision to expose the extensor retinaculum that covers the tendons in

the six compartments on the dorsal aspect of the wrist (Fig. 5-3).

radialis longus and brevis muscles in the second compartment of the

wrist. The compartment is on the radial side of Lister’s tubercle. To

expose the other compartments, incise the ulnar edge of the cut

retinaculum by sharp dissection in an ulnar direction to deroof

sequentially the four compartments on the ulnar side. Then, dissect the

radial edge of the cut extensor retinaculum radially to deroof the

first compartment. The extensor retinaculum should be preserved;

during

closure, it can be sutured underneath the extensor tendons to prevent

them from being abraded by the bones, which can be deformed grossly by

rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 5-8).

|

|

Figure 5-2 Skin incision for the dorsal approach to the wrist joint. A cross section at the distal portion of the radius is seen.

|

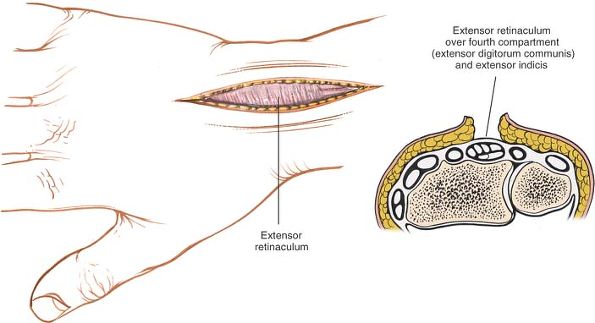

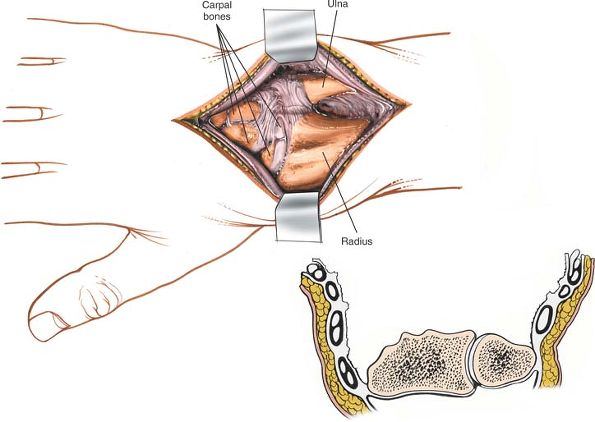

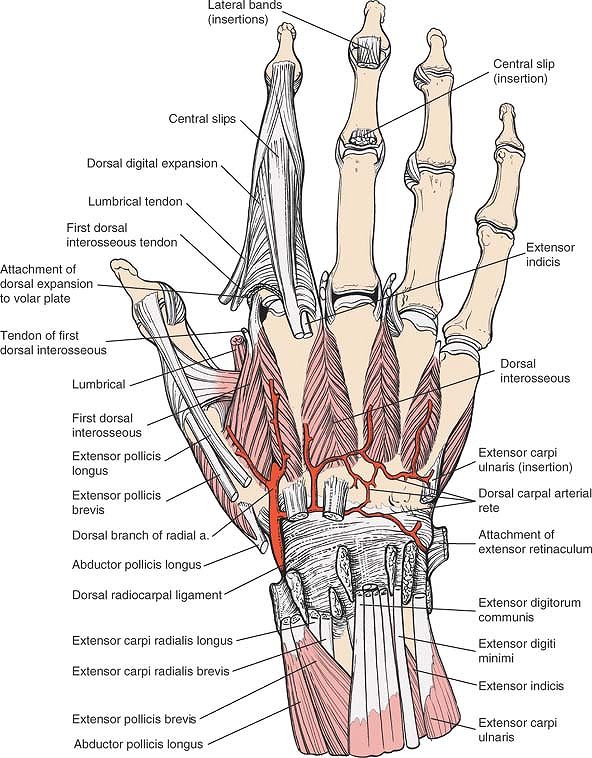

digitorum communis and extensor indicis proprius muscles in the fourth

compartment of the wrist. Mobilize the tendons of the compartment,

lifting them from their bed in an ulnar and radial direction to expose

the underlying radius and joint capsule (Fig. 5-4). Incise the joint capsule longitudinally on the dorsal aspect of the radius and carpus (Fig. 5-5).

Continue the dissection below the capsule (the dorsal radiocarpal

ligament) toward the radial and ulnar sides of the radius to expose the

entire distal end of the radius and carpal bones (Figs. 5-6 and 5-7).

brevis muscles, which attach to the bases of the second and third

metacarpals and lie in a tunnel on the radial side of Lister’s

tubercle, must be retracted radially to expose fully the dorsal aspect

of the carpus.

|

|

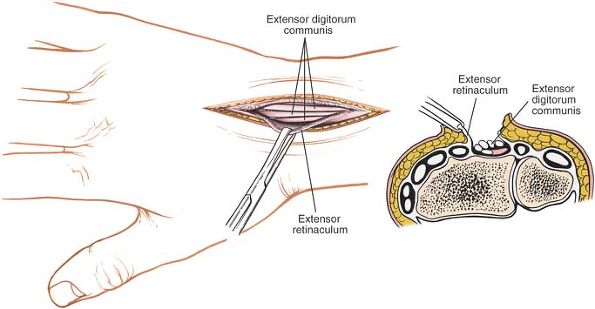

Figure 5-3

Skin flaps are developed, and the extensor retinaculum is visualized in the deeper portion of the wound. Cross section reveals the approach to the fourth tunnel, which contains the extensor digitorum communis and the extensor indicis proprius. |

|

|

Figure 5-4 The retinaculum over the fourth compartment has been opened, revealing the communis tendons.

|

|

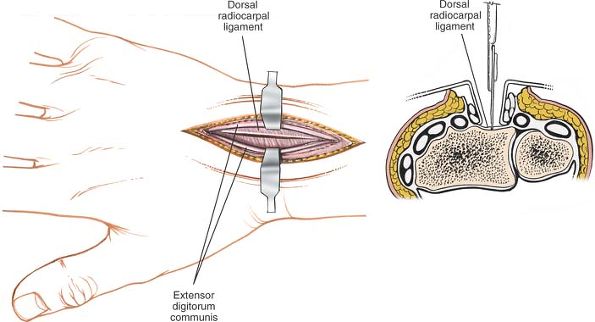

|

Figure 5-5

The extensor communis tendons and extensor indicis proprius have been retracted, revealing the dorsal radiocarpal ligament and the joint capsule, which then is incised. |

|

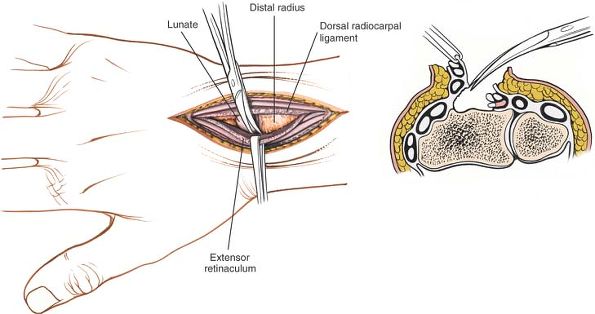

|

Figure 5-6

The dorsal radiocarpal ligament and the extensor tendons are elevated from the posterior aspect of the radius to expose the entire dorsal end of the bone. |

|

|

Figure 5-7 The extensor tendons in their compartments have been elevated to expose the distal end of the radius and ulna.

|

|

|

Figure 5-8 (A) For synovectomy, make an incision over the second compartment. (B)

Open each of the compartments sequentially from radius to ulna by incising the septum that connects the retinaculum to the carpus itself and the joint capsule. (C) Now that the compartments have been deroofed, place the retinaculum between the extensor tendons and the distal ends of the radius and ulna to provide added protection for the tendons. |

|

|

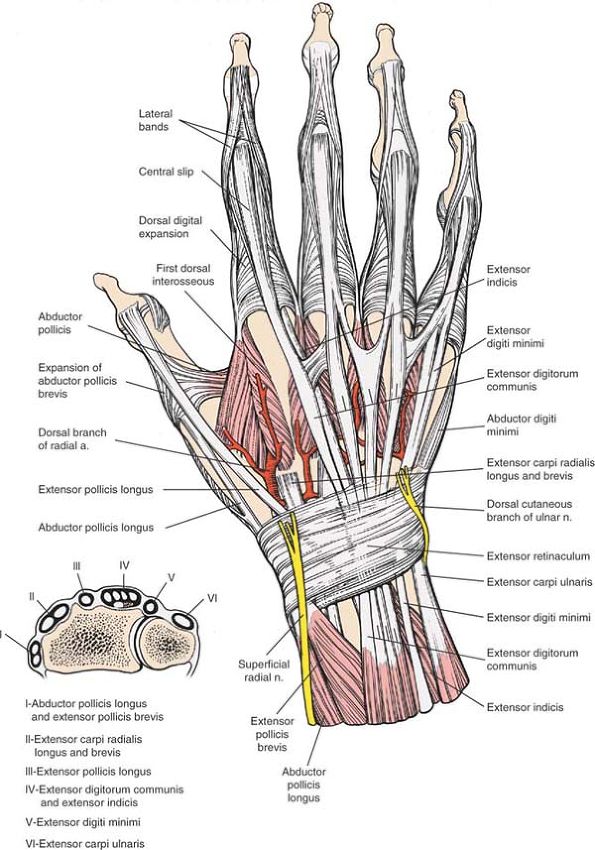

Figure 5-9 The dorsal aspect of the wrist and hand. Cross section of the distal forearm (inset). Note the compartmentalization of tendons into six distinct tunnels at the dorsal aspect of the distal forearm.

|

(superficial radial nerve) emerges from beneath the tendon of the

brachioradialis muscle just above the wrist joint before traveling to

the dorsum of the hand. The skin incision lies between skin that is

supplied by cutaneous branches of the ulnar nerve and skin that is

supplied by cutaneous branches of the radial nerve. Damage to cutaneous

nerves commonly occurs if the dissection of the flaps is begun within

the fat layer. If the skin incision is taken down to the extensor

retinaculum before the ulnar and radial flaps are elevated, the nerves

are protected by the full thickness of the fat. Take care, however, to

identify and preserve any nerve branches that are encountered during

the incision of the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 5-9).

the wrist joint on its lateral aspect. As long as the dissection at the

level of the wrist joint remains below the periosteum, the artery is

difficult to damage.

the incision cannot be extended proximally to expose the rest of the

radius. It can be extended to expose the distal half of the dorsal

aspect of the radius, however, by retracting the abductor pollicis

longus and extensor pollicis brevis muscles, which cross the operative

field obliquely.

extend the incision distally and retract the extensor tendons. (This

type of extension seldom is required in practice.) The approach

provides excellent exposure of the wrist joint and allows easy access

to all six compartments of the extensor tunnel.

joint and pass beneath the extensor retinaculum, which is a thickening

of the deep fascia of the forearm. The extensor retinaculum prevents

the tendons from “bowstringing.” Fibrous septa pass from the deep

surface of the retinaculum to the bones of the forearm, dividing the

extensor tunnel into six compartments. These septa must be separated

from the retinaculum so that each compartment can be opened in surgery

(see Fig. 5-9).

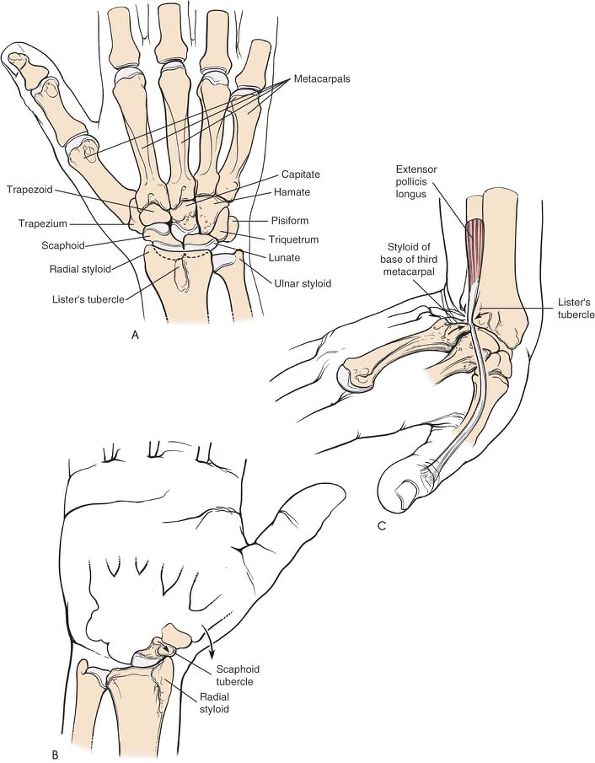

is the distal end of the lateral side of the radius. It also is the

site of attachment of the tendon of the brachioradialis muscle. Its

medial part articulates with the scaphoid bone (Fig. 5-12A).

Strong and sudden radial deviation of the wrist may cause the radial

styloid process to slam into the scaphoid and fracture it (see Fig. 5-12B). Alternatively, such a force may cause a fracture of the radial styloid.

fails to reunite or after arthritic changes in the wrist joint have

affected the radial margin of the radioscaphoid joint.

dorsoradial tubercle) is a small bony prominence on the dorsum of the

radius. The tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle angles around

its distal end, changing direction about 45° as it does so. When the

wrist is hyperextended, the base of the third metacarpal comes very

close to Lister’s tubercle, and the two bones can crush the trapped

tendon of the extensor pollicis longus. This probably is the reason the

tendon suffers delayed rupture in some cases of minimal or undisplaced

fractures of the distal radius; the tendon sustains a vascular insult

at the time of the original injury, even though it remains intact (see Fig. 5-12C).4

the skin almost perpendicularly on the dorsum of the wrist can cause

broad scarring. Nevertheless, because the skin on the wrist is so

loose, this is one of those rare occasions when a skin incision can cross a major skin crease at right angles without causing a joint contracture.

that lies obliquely across the dorsal aspect of the wrist. Its radial

side is attached to the anterolateral border of the radius; its ulnar

border is attached to the pisiform and triquetral bones. (Were it

attached to both bones of the forearm instead, pronation and supination

would be impossible, because its fibrous tissue is incapable of

stretching the necessary 30%.)

retinaculum to the bones of the carpus, dividing the extensor tunnel

into six compartments (Fig. 5-10). From the radial (lateral) to the ulnar (medial) aspect, the compartments contain the following:

-

Abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis.

These tendons lie over the lateral aspect of the radius. They may

become trapped or inflamed beneath the extensor retinaculum in their

fibroosseous canal, producing de Quervain’s disease (tenosynovitis

stenosans). -

Extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis.

These muscles run on the radial side of Lister’s tubercle before

reaching the dorsum of the hand. The tendon of the extensor carpi

radialis longus is used frequently in tendon transfers. The tendons run

in separate synovial sheaths.![]() Figure 5-10

Figure 5-10

Anatomy of the distal forearm, with the extensor retinaculum excised

and the septa remaining. The retinaculum on the ulnar side inserts into

the triquetrum and pisiform bones. -

Extensor pollicis longus.

This tendon passes into the dorsum of the hand on the ulnar side of

Lister’s tubercle. It may rupture in association with fractures or

rheumatoid arthritis. The oblique passage of this tendon on the dorsal

aspect of the wrist creates significant problems for plate fixation of

fractures of the distal radius. Tendon irritation and even rupture may

occur due to abrasion of the tendon on the surface of the plate.

Similar problems apply to a lesser degree with all the other extensor

tendons.6 -

Extensor digitorum communis and extensor indicis. The indicis tendon is used commonly in tendon transfers.

-

Extensor digiti minimi. This tendon overlies the distal radioulnar joint.

-

Extensor carpi ulnaris. This tendon passes near the base of the ulnar styloid process. It is used sometimes in tendon transfers (Fig. 5-11; see Fig. 5-10).

|

|

Figure 5-11

The extensor tendons have been removed, revealing the dorsal radiocarpal ligament. The radial artery is seen piercing the first dorsal interosseous muscle and contributing to the dorsal carpal rete. Note the hood mechanism for the index finger; contributions are made to it by the first dorsal interosseous and the first lumbrical muscles. |

|

|

Figure 5-12 (A) Dorsal aspect of the bones of the distal forearm, wrist, and proximal hand. (B)

A strong and sudden radial deviation of the wrist may cause the radial styloid process to impinge on the scaphoid tubercle and fracture it. (C) With sudden extreme dorsiflexion of the wrist, as when one falls on an outstretched hand, the extensor pollicis longus tendon may be trapped or crushed between the dorsal radial tubercle (Lister’s tubercle) and the base of the third metacarpal. |

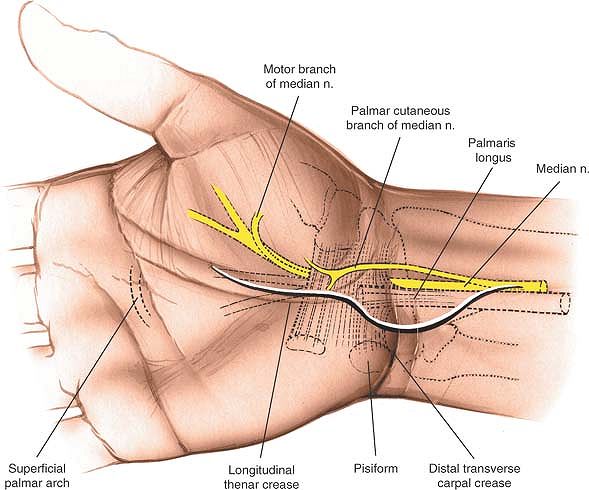

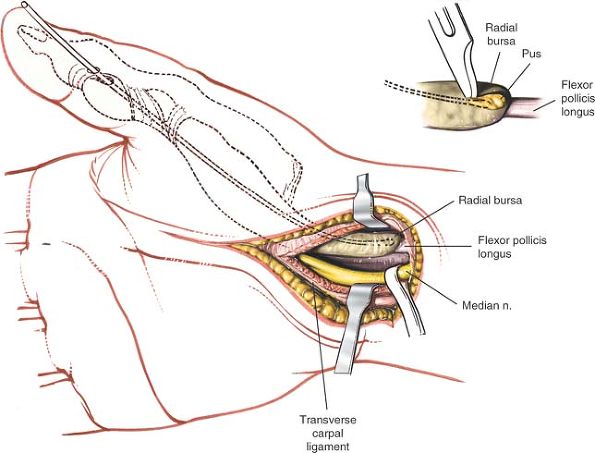

tunnel is one of the most common operations of the hand. Two anatomic

structures, the motor and palmar cutaneous branches of the median

nerve, determine how the tunnel is approached. Both structures vary

considerably in the paths they take; they are so unpredictable that

“blind” procedures, which are acceptable elsewhere, must be avoided.

The tunnel must be decompressed through a full incision and under

direct vision. The uses of the incision include the following:

-

Decompression of the median nerve7,8

-

Synovectomy of the flexor tendons of the wrist

-

Excision of tumors within the carpal tunnel

-

Repair of lacerations of nerves or tendons within the tunnel

-

Drainage of sepsis tracking up from the mid-palmar space

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

certain fractures and dislocations of the distal radius and carpus,

including volar lip fractures of the radius

forearm on a hand table in the supinated position so that the palm

faces upward. Use an exsanguinating bandage (Fig. 5-13).

|

|

Figure 5-13 Position of the patient for volar approaches to the wrist and hand.

|

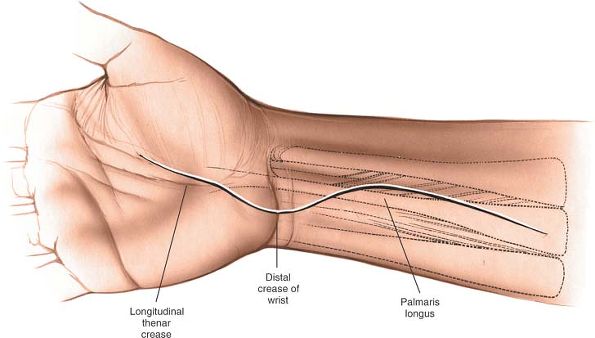

muscle bisects the anterior aspect of the wrist. Its distal end bisects

the anterior surface of the carpal tunnel. It is easy to palpate in the

distal forearm if the patient is instructed to pinch the fingers

together and flex the wrist.

crease, about one third of the way into the hand. Curve it proximally,

remaining just to the ulnar side of the thenar crease, until the

flexion crease of the wrist is almost reached: to avoid problems in

skin healing, do not wander into the thenar crease itself. Then, curve

the incision toward the ulnar side of the forearm so that the flexion

crease is not crossed transversely (Fig. 5-14).

|

|

Figure 5-14

The incision for the volar approach to the wrist. The incision should be made on the ulnar side of the palmaris longus tendon to protect the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. |

anatomic dissection in which the major nerves are identified, dissected

out, and preserved. No muscles are transected except, on occasion, some

fibers of the abductor pollicis brevis and palmaris brevis that cross

the midline.

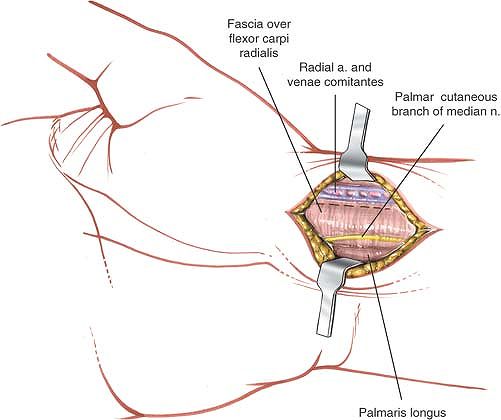

palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, which usually presents on

the ulnar side of the flexor carpi radialis, has a variable course.

Dissection should be carried out meticulously, with particular

attention paid to the location of the nerve (see Fig. 5-14). After the fat is incised, the fibers of the superficial palmar fascia come into view; section them in line with the incision.

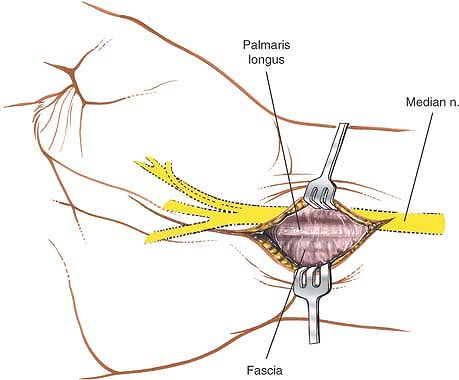

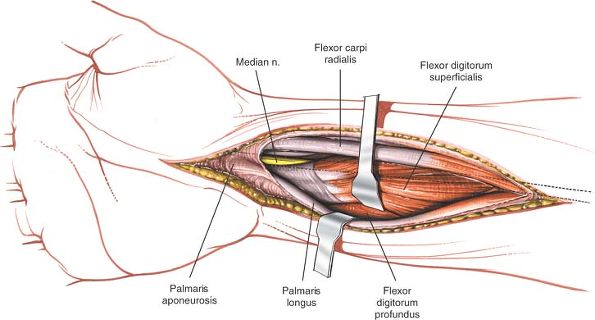

insertion of the palmaris longus muscle into the flexor retinaculum

(the transverse carpal ligament; Fig. 5-15).

Retract the tendon toward the ulna and identify the median nerve

between the tendons of the palmaris longus muscle and the flexor carpi

radialis muscle. The nerve lies closer to the palmaris longus than to

the flexor carpi radialis (Fig. 5-16).

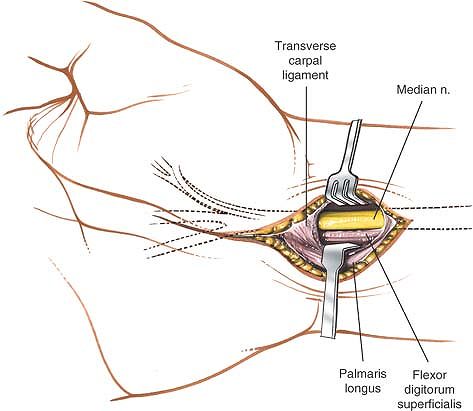

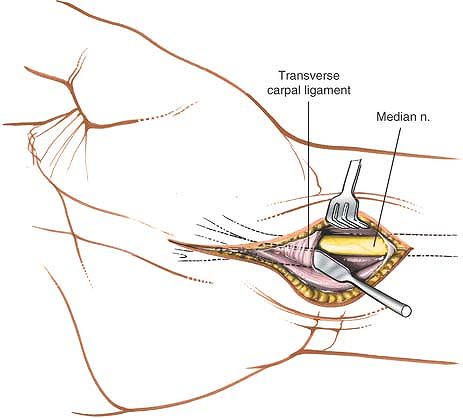

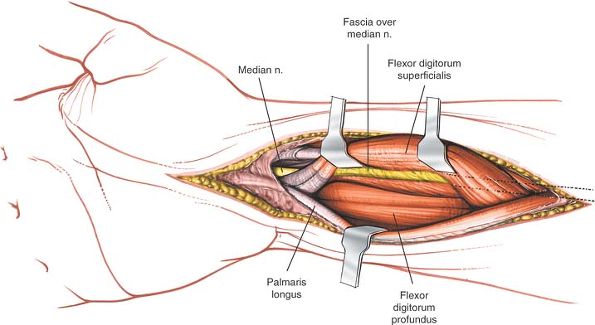

dissector) down the carpal tunnel between the flexor retinaculum and

the median nerve (Fig. 5-17). Carefully incise

the retinaculum, cutting down on the dissector to protect the nerve.

Make the incision on the ulnar side of the nerve to avoid possible

damage to its motor branch to the thenar muscle. Divide the entire

length of the retinaculum (Fig. 5-18).

|

|

Figure 5-15 The skin is retracted, and the deep fascia and tendon of the palmaris longus are inspected.

|

|

|

Figure 5-16

The deep fascia is incised. The palmaris longus is retracted toward the ulna, revealing the median nerve as it enters the carpal tunnel. |

|

|

Figure 5-17 A spatula is placed under the transverse carpal ligament to protect the median nerve as the ligament is incised.

|

|

|

Figure 5-18

The transverse carpal ligament is released on the ulnar side of the nerve to avoid damage to the motor branch of the thenar muscle. |

usually arises from the anterolateral side of the median nerve just as

the nerve emerges from the carpal tunnel. The motor branch then curves

radially and upward to enter the thenar musculature between the

abductor pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis brevis muscles. Sometimes,

however, the motor branch arises within the tunnel and pierces the

flexor retinaculum to reach the thenar musculature. In these rare

cases, the motor nerve itself may have to be decompressed before the

patient’s symptoms will be relieved fully (see Fig. 5-18).

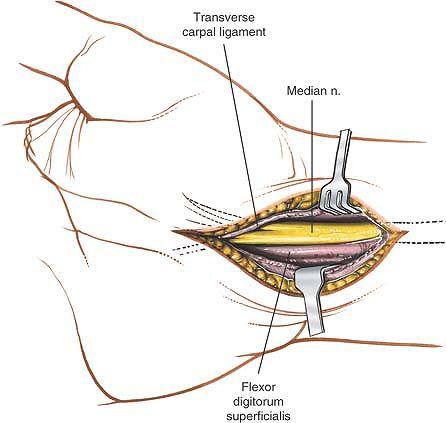

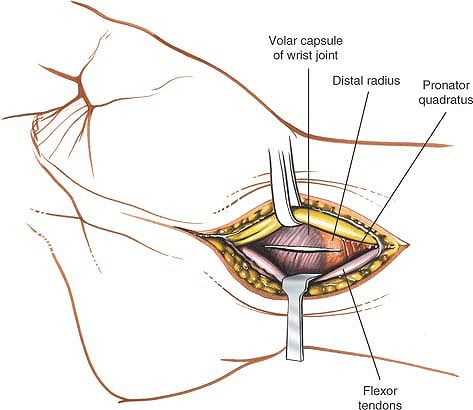

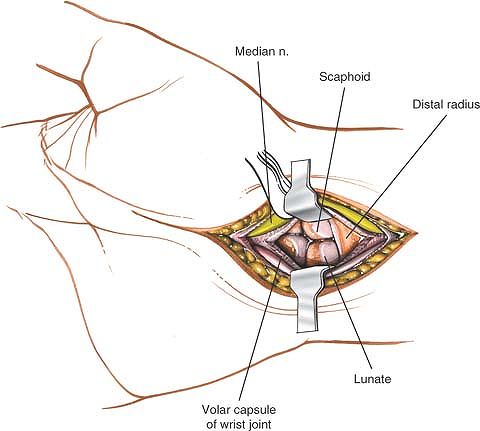

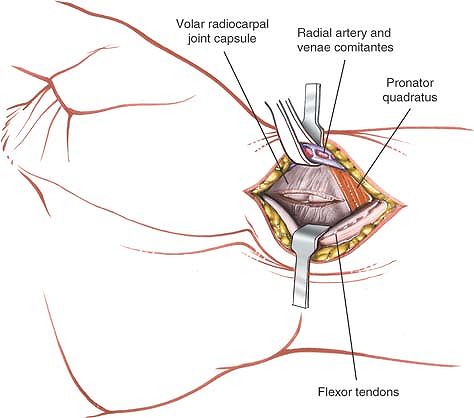

aspect of the wrist joint. If this is required, mobilize the median

nerve in the carpal tunnel and retract it radially to avoid stretching

its motor branch. Next, mobilize and retract the flexor tendons in the

carpal tunnel (Fig. 5-19). Incising the base of

the tunnel longitudinally exposes the volar aspect of the carpus.

Extending the incision proximally provides access to the volar aspect

of the wrist joint and the distal radius (Fig. 5-20).

The most convenient approach for access to the volar aspect of the

distal radius is the distal portion of the anterior approach to the

radius (see Chapter 4).

|

|

Figure 5-19

The median nerve is retracted radially and the flexor tendons are retracted toward the ulna, revealing the distal radius and joint capsule. An incision then is made into the capsule to expose the carpus. |

arises 5 cm proximal to the wrist joint and runs down along the ulnar

side of the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis muscle before crossing

the flexor retinaculum. The greatest threat to this nerve occurs if the

skin incision is not angled to the ulnar side of the forearm (see Fig. 5-14).

to the thenar muscles exhibits considerable anatomic variation. The

risk to the nerve is minimized if the incision is made into the carpal

tunnel on the ulnar side of the median nerve (see Applied Surgical Anatomy of the Volar Aspect of the Wrist and Fig. 5-32).

crosses the palm at the level of the distal end of the outstretched

thumb. Blind slitting of the flexor retinaculum may damage this

arterial arcade if the instrument passes too far distally. The arch is

in no danger if the flexor retinaculum is cut carefully under direct

observation for its entire length (see Figs. 5-14 and 5-32).

Minimal access approaches to divide the flexor retinaculum rely on

arthroscopic visualization of the anatomical structures to ensure their

preservation.

|

|

Figure 5-20 Incise the joint capsule to expose the carpus.

|

approach can be extended to expose the median nerve. To accomplish

this, extend the skin incision proximally, running it up the middle of

the anterior surface of the forearm (Fig. 5-21).

Incise the deep fascia of the forearm between the palmaris longus and

flexor carpi radialis muscles. Retract the flexor carpi radialis in a

radial direction and the palmaris longus in an ulnar direction,

exposing the muscle belly of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle

in the distal two

thirds of the forearm (Fig. 5-22).

The median nerve adheres to the deep surface of the flexor digitorum

superficialis, held there by fascia. Thus, if the flexor digitorum

superficialis is reflected, the nerve goes with it (Fig. 5-23).

|

|

Figure 5-21 Extend the wrist incision proximally to expose the distal forearm and median nerve.

|

|

|

Figure 5-22

Incise the fascia on the forearm between the palmaris longus and the flexor carpi radialis to expose the tendons and muscles on the flexor digitorum superficialis. |

|

|

Figure 5-23

Reflect the flexor digitorum superficialis and note that the median nerve moves with it, because it is attached to the muscle via the posterior fascia of the muscle. |

incision can be extended into a volar zigzag approach for any of the

fingers, providing complete exposure of all the palmar structures (see Volar Approach to the Flexor Tendons and Fig. 5-38).

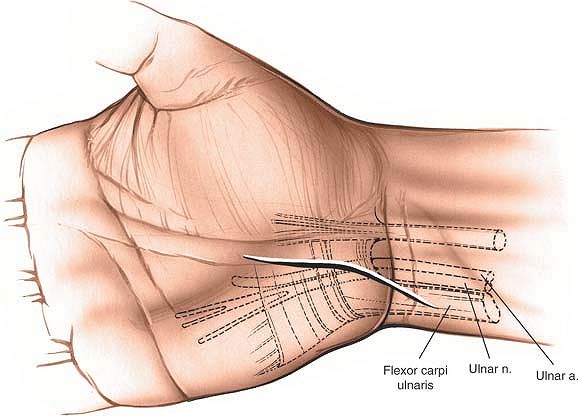

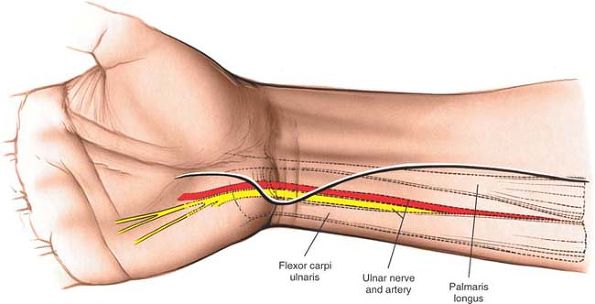

nerve at the wrist. It is used primarily to decompress the canal of

Guyon in cases of ulnar nerve compression. It also permits exploration

of the ulnar nerve in cases of trauma. The approach is freely extensile

proximally, allowing exposure of the nerve all the way up the forearm.

the hand on a hand table in the supinated position, so that the palm

faces upward. Use an exsanguinating soft bandage, then inflate a

tourniquet (see Fig. 5-13).

|

|

Figure 5-24 Incision for the exposure of the ulnar nerve in the canal of Guyon.

|

the hypothenar eminence and crossing the wrist joint obliquely at about

60°. Extend the incision onto the volar aspect of the distal forearm.

The incision should be about 5 to 6 cm long (Fig. 5-24).

anatomic dissection in which the nerve and vessels are dissected out

and preserved.

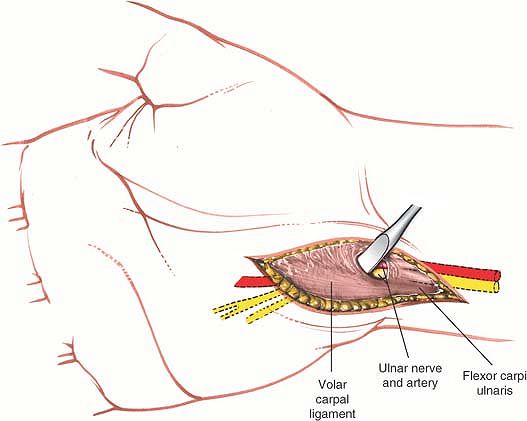

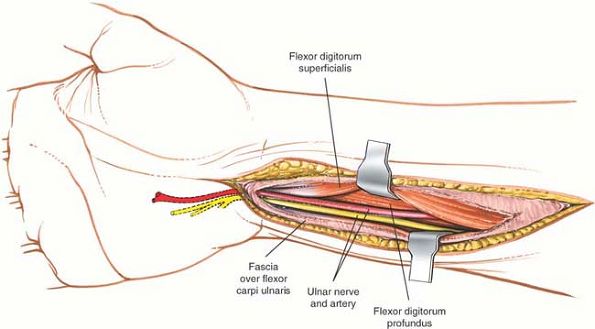

identify the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris in the proximal end of

the wound (Fig. 5-25). Mobilize the tendon by

incising the fascia on its radial border, and retract the muscle and

tendon in an ulnar direction to reveal the ulnar nerve and artery (Fig. 5-26).

|

|

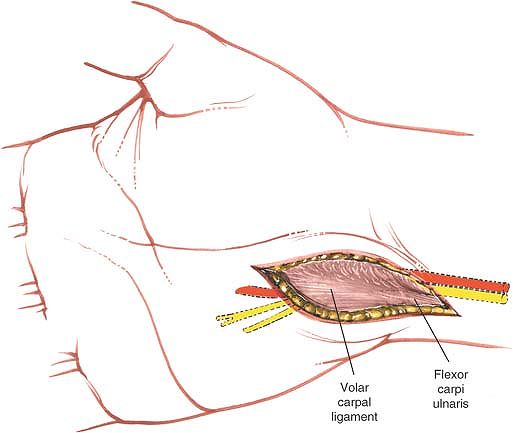

Figure 5-25 The volar carpal ligament is seen as a continuation of the deep palmar fascia and fibers of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

|

|

|

Figure 5-26 The volar carpal ligament is isolated and the nerve is protected in preparation for sectioning of the volar carpal ligament.

|

|

|

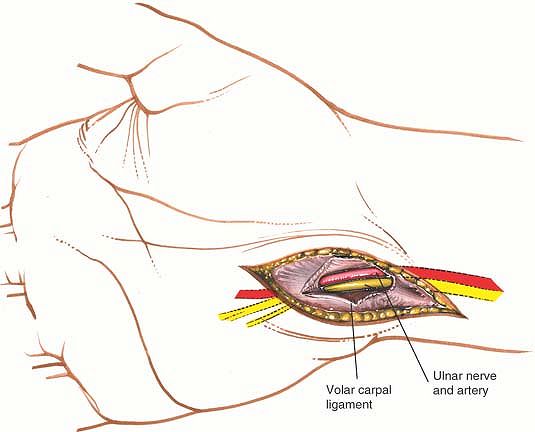

Figure 5-27 The roof of the canal has been incised, revealing the ulnar nerve and artery.

|

fibrous tissue, the volar carpal ligament. During this procedure, take

great care to protect the nerve and vessel. The ulnar nerve now is

exposed across the wrist joint; the canal of Guyon is decompressed (Fig. 5-27).

-

When the fascia on the radial side of the

flexor carpi ulnaris is incised to allow retraction of the muscle,

during superficial surgical dissection -

When the volar carpal ligament is incised, during deep surgical dissection

the skin incision proximally on the anterior aspect of the forearm,

running it longitudinally up the middle of the forearm (Fig. 5-28).

Incise the deep fascia in line with the incision and identify the

radial border of the flexor carpi ulnaris. Develop a plane between the

flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is supplied by the ulnar nerve) and

the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle (which is supplied by the

median nerve), retracting the flexor carpi ulnaris toward the ulna to

reveal the ulnar nerve. This incision can expose the ulnar nerve almost

to the level of the elbow joint (Fig. 5-29), where it passes between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle.

|

|

Figure 5-28 Explore the ulnar nerve proximally in the forearm.

|

|

|

Figure 5-29

Develop the plane between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum superficialis. In the depth of the wound, the ulnar nerve is visualized running under the reflected head of the flexor carpi ulnaris. |

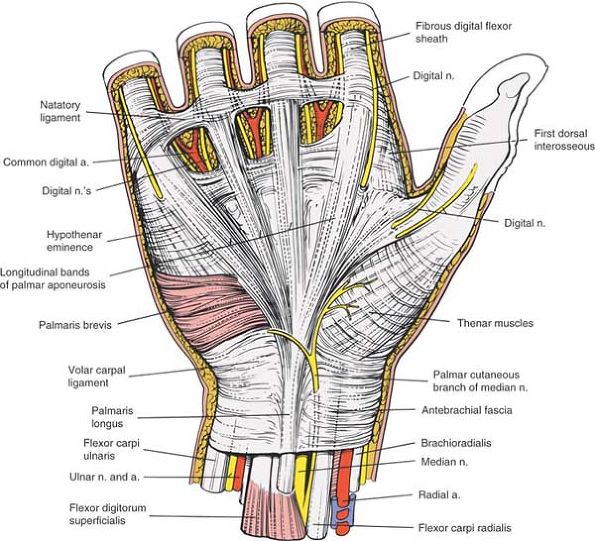

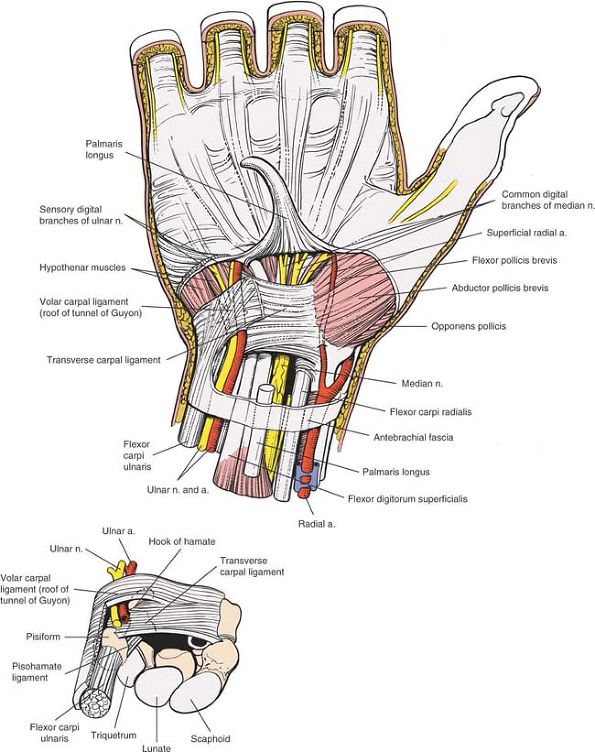

surface of the carpus. Its base is formed by the deeply concave surface

of the volar aspect of the carpal bones, and its roof is formed by the

flexor retinaculum (Fig. 5-30). The ulnar nerve

runs over the surface of the flexor retinaculum; it is enclosed in its

own fibro-osseous canal, the canal of Guyon (Fig. 5-31).

|

|

Figure 5-30

Superficial anatomy of the wrist and palm. Note the course of the cutaneous branch of the median nerve. The longitudinal bands of the palmar aponeurosis are continuations of the palmaris longus tendon. |

-

The pisiform.

This is located on the ulnar border of the wrist. The pisiform is a

mobile sesamoid bone lying within the tendon of the flexor carpi

ulnaris muscle. The bone was sometimes used by artisans to tap nails

into soft wood or leather.

P.207P.208

Stress fractures have been noted in cobblers who use the pisiform for this purpose. Figure 5-31

Figure 5-31

The palmar aponeurosis and fascia have been elevated to reveal the

transverse carpal ligament. The fascia of the forearm and the

expansions of the flexor carpi ulnaris (volar carpal ligament) are left

intact where they form the roof of the tunnel of Guyon. The canal of

Guyon looking from proximal to distal (inset).

The transverse carpal ligament forms the floor of the tunnel of Guyon;

the roof is formed by the volar carpal ligament, which is a

condensation of the fascia of the forearm and expansions of the flexor

carpi ulnaris tendon. The canal is formed medially by the pisiform bone

and laterally by the hook of the hamate bone. -

The hook of the hamate.

This is slightly distal and radial to the pisiform. To locate it, place

the interphalangeal joint of the thumb on the pisiform, pointing the

tip toward the web space between the thumb and index finger, and rest

the tip of the thumb on the palm. The hook of the hamate lies directly

under the thumb. Because it is buried under layers of soft tissue, one

must press firmly to find its rather shallow contours. The deep branch

of the ulnar nerve lies on the hook, and neurapraxia of the nerve has

been described in cases of fracture. -

The ridge of the trapezium.

The trapezium lies on the radial side of the carpus, where it

articulates with the first metacarpal. To palpate the ridge, identify

the joint between the trapezium and the thumb’s metacarpal bone by

moving the joint passively. The ridge feels like a prominent lump on

the volar aspect of the trapezium (see Fig. 5-36A). -

The tubercle of the scaphoid.

This small protuberance is barely palpable just distal to the distal

end of the radius on the volar aspect of the wrist joint (see Figs. 5-35 and 5-36A).

the groove on the trapezium, converting the groove into a tunnel

through which the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis muscle runs

before it attaches to the base of the second and third metacarpals (see

Figs. 5-35 and 5-36A).

-

Tendon of the palmaris longus.

The palmaris longus is a vestigial muscle of no functional importance.

Its tendon is used frequently for tendon grafting. It is important to

test for the presence of this tendon before surgery, because it is

absent in about 10% of the population. The tendon also is used as an

anatomic landmark for the injection of steroid into the carpal tunnel.

If the patient is asked to flex the wrist against resistance, the

tendon of the palmaris longus (if it is present) is easily palpable

together with the thicker and more radially located tendon of the

flexor carpi radialis. The easily defined gap between the two tendons

is the site where the needle should be inserted for injection of the

carpal tunnel. The needle should be inserted here dorsally and distally

at an angle of almost 45°. Note also that because the carpal tunnel is

a distensible space, if problems are encountered in injecting it, then

the tip of the needle either is still in the flexor retinaculum or is

imbedded in one of the tendons in the tunnel. Correctly positioned

syringes should enter the space without encountering much resistance to

pressure. -

Palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. The course of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve may vary in four important ways (see Fig. 5-30):

-

Normally, the nerve branches off 5 cm

proximal to the wrist. It runs along the ulnar side of the tendon of

the flexor carpi radialis before crossing the flexor retinaculum. On

rare occasions, the nerve actually may be enclosed by parts of the

flexor retinaculum and, thus, may run in a tunnel of its own on the

wrist.The nerve divides into two major branches, medial and

lateral, while crossing the flexor retinaculum. The lateral is the

larger branch. Both supply the skin of the thenar eminence. -

Less often, the nerve arises from the median nerve in two distinct branches, which travel separately across the wrist.9

-

The palmar cutaneous branch may arise within the carpal tunnel and penetrate the flexor retinaculum to supply the skin of the thenar eminence.

-

The palmar cutaneous branch may be

absent, replaced by a branch derived from the radial nerve, the

musculocutaneous nerve, or the ulnar nerve.9The skin incision described above avoids cutting the

nerve by angling across the distal forearm in an ulnar direction. One

must be aware, however, that considerable variability exists in the

course of the nerve. Because damage can result in the formation of a

painful neuroma, transverse incisions on the volar aspect of the distal

forearm must be avoided. (Compression lesions of the nerve have been

reported, but these are rare.)10,11

-

-

Ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve runs down the volar surface of the distal forearm under cover of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (see Fig. 5-31).

The ulnar artery lies on its radial side. The tendon of the flexor

carpi ulnaris inserts into the pisiform, which then joins with the

hamate and fifth metacarpal via ligaments. Just proximal to the wrist,

the artery and nerve emerge from under the muscle to pass over the

flexor retinaculum (the transverse carpal ligament) of the wrist (see Fig. 5-31).

the nerve, and, finally, the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris (see Fig. 5-31).

damage by lacerations. The grim triad of lacerations of the tendon of

the flexor carpi ulnaris, the ulnar artery, and the ulnar nerve is a

common sequela of falling through a window with the ulnar border of the

wrist flung forward to protect the face.

covered with a tough fibrous tissue that is continuous with the deep

fascia of the forearm, the volar carpal ligament. The tunnel thus

formed, the canal of Guyon, has four boundaries: a floor, the flexor

retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament); a medial wall, the pisiform;

a lateral wall, the hamate; and a roof, the volar carpal ligament

(distal fascia of the forearm; see Fig. 5-31).

|

|

Figure 5-32

The palmar aponeurosis has been resected further distally to expose the superficial palmar arterial arch. The transverse carpal ligament also has been resected. The median nerve lies superficial to the tendons of the profundus, but at the same level with the superficialis muscle tendons. Note the motor branch of the median nerve to the thenar muscles. The location of its division from the median nerve is quite variable. |

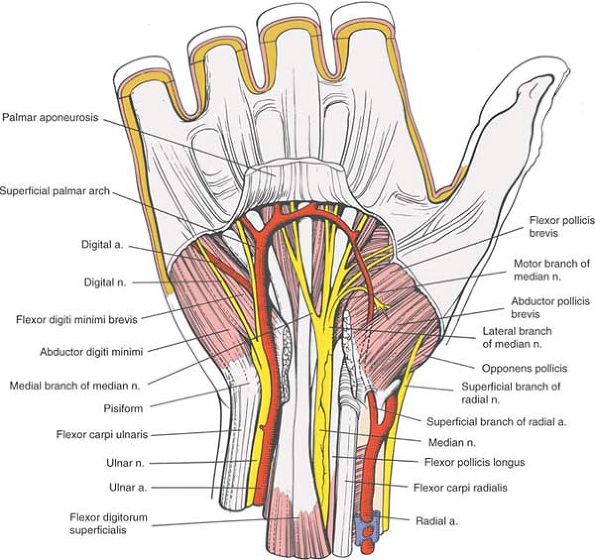

branches. The superficial branch supplies the palmaris brevis muscle

and the skin of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. The

deep branch supplies all the small intrinsic muscles of the hand,

except those of the thenar eminence and the radial two lumbricals (see Figs. 5-32, 5-33, 5-34 and 5-35).

|

|

Figure 5-33

The palmar aponeurosis has been elevated up to its attachment to the digital flexor sheaths. Its deeper attachments to the carpal plate and bone have been cut. The flexor tendons and digital nerves are shown in continuity, as are the superficial palmar arch and the thenar and hyperthenar muscles. Note that the digital nerves and vessels go deep or dorsal to the natatory ligaments. Flexor Pollicis Brevis. Origin. Flexor retinaculum. Insertion. Radial border of proximal phalanx of thumb. Action. Flexor of metacarpophalangeal joint of thumb. Nerve supply. Median nerve (motor or recurrent branch).

Abductor Pollicis Brevis. Origin. Flexor retinaculum and tubercle of scaphoid. Insertion. Radial side of base of proximal phalanx of thumb. Action. Abduction of thumb at metacarpophalangeal joint and rotation of proximal phalanx of thumb. Nerve supply. Median nerve (motor or recurrent branch).

|

|

|

Figure 5-34

Portions of the thenar and hypothenar muscles have been resected to reveal their layering. The ulnar nerve passes between the origin of the abductor digiti minimi and the flexor digiti minimi. In the thenar region, the course of the flexor pollicis longus is seen as it crosses between the two heads of the flexor pollicis brevis. Portions of the long flexors of the fingers have been resected to show their layering. The superficial palmar arch runs superficial to the tendons, whereas the deep palmar arch is immediately deep to the tendons. Note that potential spaces develop on the undersurface of the flexor tendons and their sheaths, and on the deep intrinsic muscles of the hand, the interosseous on the hyperthenar side and the adductor pollicis on the thenar side. A septum that runs from the undersurface of the flexor tendons to the third metacarpal divides the two spaces. More distally, the superficial transverse ligament has been resected, revealing the course of the lumbricals and the digital vessels that run superficial or palmar to the deep transverse metacarpal ligaments. Adductor Pollicis. Origin.

Oblique head from bases of second and third metacarpals, trapezoid, and capitate. Transverse head from palmar border of third metacarpal. Insertion. Ulnar side of base of proximal phalanx of thumb via ulnar sesamoid. Action. Adduction of thumb. Opposition of thumb. Nerve supply. Deep branch of ulnar nerve. Opponens Pollicis. Origin. Flexor retinaculum. Insertion. Radial border of thumb metacarpal. Action. Opposition of metacarpal bone of thumb. Nerve supply. Median nerve (motor or recurrent branch).

|

|

|

Figure 5-35

The deepest layer of the palm is revealed. The deep palmar arterial arch lies deep to the long flexor tendon and superficial to the interosseous muscles. It crosses the palm with the deep branch (motor branch) of the ulnar nerve. The nerve supplies all the interosseous muscles. More distal, the interosseous muscles are seen running deep (dorsal) to the deep transverse ligament. The deep transverse metacarpal ligaments attach to the palmar plate, which is seen on the fifth metacarpal. The pulleys of the thumb are seen in relationship to the digital nerves. |

forearm deep to the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle. Just above

the wrist, it becomes superficial and lies between the tendons of the

palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis muscles. It enters the palm

by traversing the carpal tunnel (see Fig. 5-31).

pollicis longus muscles. The superficialis tendons lie toward the ulnar

side of the nerve. At the distal border of the flexor retinaculum, the

nerve divides into two branches (see Figs. 5-32 and 5-33).

-

The medial branch

sends cutaneous branches to the adjacent sides of the ring and middle

fingers, and to the adjacent sides of the middle and index fingers. -

The lateral branch

sends cutaneous branches to the radial side of the index finger and to

both sides of the thumb. The lateral branch usually also sends off the

motor, or recurrent, nerve (see Fig. 5-32), which is the key surgical landmark and major surgical danger in carpal tunnel decompression.

-

The classic course (seen in 50% of

patients). The branch arises from the volar radial aspect of the median

nerve distal to the radial end of the carpal tunnel. The nerve hooks

radially and upward to enter the thenar muscle group between the flexor

pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis brevis muscles.The position of the motor branch can be estimated by

drawing one vertical line from the web space between the middle and

index fingers, drawing another from the radial origin of the first web

space, then connecting to the hook of the hamate (Kaplan’s cardinal

line). The intersection of these two lines marks the origin of the

motor branch (see Fig. 5-36B).12 -

A variation that occurs in about 30% of

patients. The branch arises from the anterior surface of the nerve

within the carpal tunnel. It passes through the tunnel with its parent

nerve and hooks around the distal end of the flexor retinaculum to

enter the thenar group between the flexor pollicis brevis and abductor

pollicis brevis muscles. -

A variation that occurs in about 20% of

patients. The branch arises from the anterior surface of the nerve

within the carpal tunnel. It travels radially to pierce the flexor

retinaculum and enter the thenar group of muscles between the abductor

pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis brevis muscles.13 -

A rare variation. The branch arises from the ulnar side of the median nerve.14

It crosses the median nerve within the tunnel, then hooks around the

distal end of the flexor retinaculum to enter the thenar muscle group.

It also may pass through the flexor retinaculum and lie anterior to it.15 -

Another rare variation. The nerve arises

from the anterior surface of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel.

At the distal end of the flexor retinaculum, the branch hooks radially

over the top of the retinaculum. The nerve crosses the distal part of

the retinaculum almost transversely before entering the thenar group of

muscles. -

A very rare variation (multiple motor branches).16 Double nerves may follow any of the courses described above.

-

A third rare variation (high division of the median nerve).17

The nerve may divide into medial and lateral branches high up in the

forearm. The thenar branch, originating from the lateral branch, may

leave the carpal tunnel either in the conventional manner or by

piercing the flexor retinaculum on its radial side.

is exposed. If the tunnel is opened on the ulnar side of the nerve, the

motor branch will be preserved unless it lies on the same side.

Patients with exceptionally rare variations usually have large palmaris

brevis muscles, which should alert the surgeon to the possibility

during the approach.10

ring fingers are superficial to the tendons of the index and little

fingers. This arrangement dictates correct repair in cases of multiple

tendon laceration (see Fig. 5-31).

to the tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis. The tendon to the

index finger is separate; the other three still may be attached

partially to each other as they pass through the carpal tunnel (see Fig. 5-31).

that of the flexor carpi radialis and is found on the most radial

aspect of the canal at the same depth as the profundus tendons (see Figs. 5-31 and 5-34).

retinaculum to lie in the groove of the trapezium before it inserts

into the bases of the second and third metacarpals. It does not pass

through the carpal tunnel (see Fig. 5-35).

|

|

Figure 5-36 (A)

The bones of the wrist and palm and the proximal metacarpals are seen in relationship to the creases of the wrist. The necks of the metacarpals are at the level of the distal palmar crease. The distal wrist crease runs from the proximal portion of the pisiform to the proximal portion of the tubercle of the scaphoid and marks the proximal level of volar carpal ligament. The proximal transverse palmar crease is at the radiocarpal joint. (B) Kaplan’s cardinal line. Used to locate the motor branch of the median nerve to the thenar muscles. |

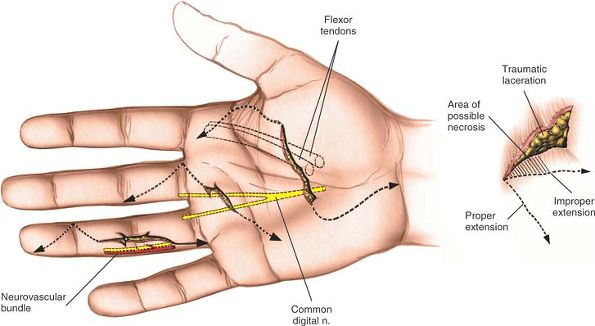

It also provides excellent exposure of both neurovascular bundles in

the finger. The skin incision can be extended into the palm, the volar

surface of the wrist, and the anterior surface of the forearm, making

it a suitable approach in cases of trauma, where many levels may have

to be exposed. Its other major advantage is that many skin lacerations

can be incorporated into the skin incision. Its uses include the

following:

-

Exploration and repair of flexor tendons

-

Exploration and repair of digital nerves and vessels

-

Exposure of the fibrous flexor sheath for drainage of pus

-

Excision of tumors within the fibrous flexor sheath

-

Excision of palmar fascia in Dupuytren’s contracture

arm abducted and lying on an arm board. Adjust the height of the table

to make sitting comfortable. Most right-handed surgeons prefer to sit

on the ulnar side of the affected arm. An exsanguinating bandage and

tourniquet, as well as good lighting, are essential (see Fig. 5-13).

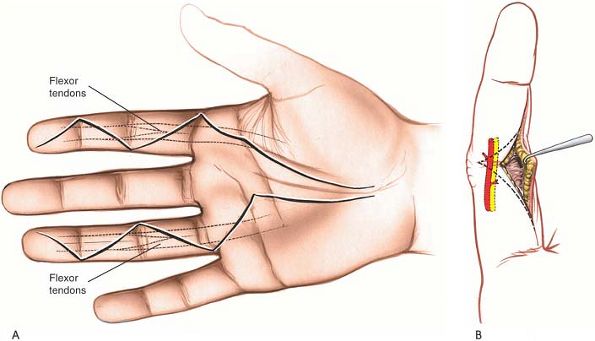

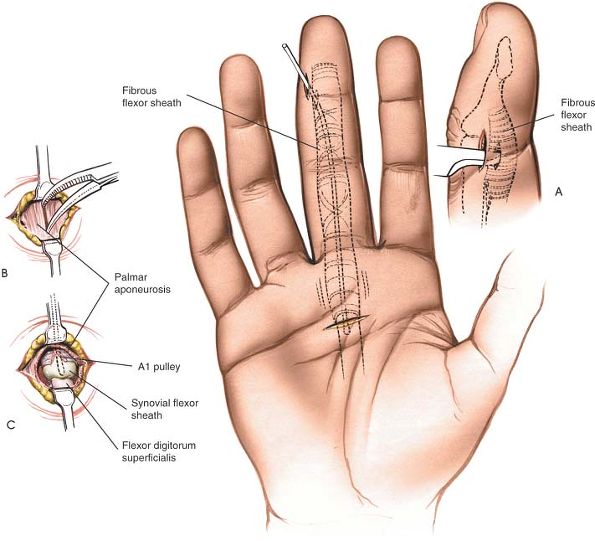

well distal to the metacarpophalangeal joint. The course of the volar

zigzag incision takes these creases into account, running diagonally

across the finger between creases (Fig. 5-37).

|

|

Figure 5-37 The relationship of the skin creases to the tendons and joints of the wrist and hand is seen.

|

methylene blue to outline the proposed site. The angles of the zigzag

should be about 90° to each other (or to the transverse skin crease);

angles considerably less than 90° to each other may lead to necrosis of

the corners (Fig. 5-38A).

The angles should not be placed too far in a dorsal direction;

otherwise, the neuromuscular bundle may be damaged when the skin flaps

are mobilized (see Fig. 5-38B). Of course, the basic zigzag pattern should be modified to accommodate any preexisting lacerations (Fig. 5-39).

|

|

Figure 5-38 (A) Basic zigzag incision for exposure of the flexor tendons of the palm and fingers. (B) If an incision is placed too far laterally or medially, the neurovascular bundle may be damaged.

|

|

|

Figure 5-39

The basic zigzag pattern should be adapted to preexisting lacerations for exploration of the underlying structures. When adapting the skin incisions to previously existing lacerations, attempt to maintain an angle of about 90° to prevent necrosis of the corners of the incision (inset). |

site of the incision is innervated by nerves coming from either side of

the incision, so no areas of anesthesia are created.

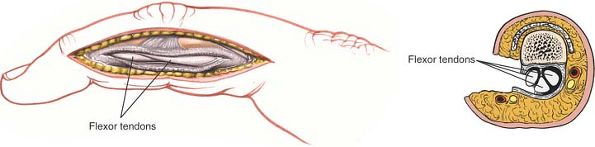

starting at the apex. Elevate the flaps along with some underlying fat.

Do not mobilize the flaps widely until the level of the flexor sheath

is reached, to ensure thick flaps and reduce the risk of skin flap

necrosis (Fig. 5-40).

|

|

Figure 5-40

Elevate thick skin flaps. Stay as close to the sheath as possible to prevent damage to the laterally placed neurovascular structures. |

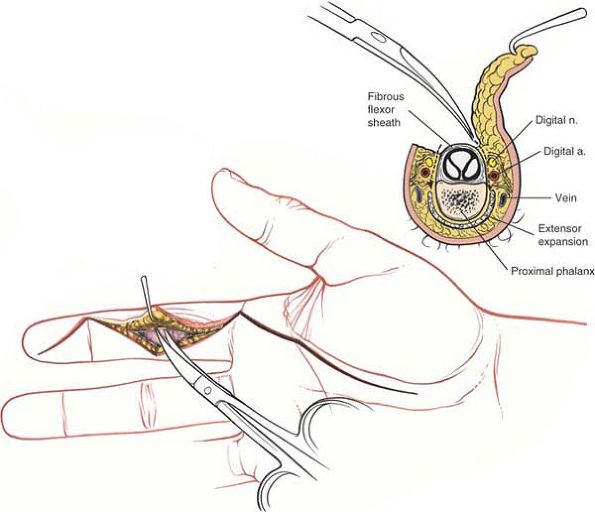

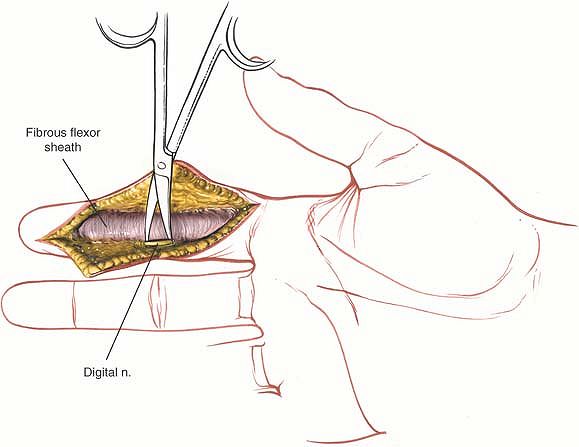

the subcutaneous tissues at the lateral border of the fibrous flexor

sheath. The neurovascular bundle is separated from the volar

subcutaneous flap by a thin layer of fibrous tissue known as Grayson’s

ligament. This layer must be opened for full exposure of the

neurovascular bundle. The easiest way to pry the tissues apart is to

open gently a small pair of closed scissors so that the blades separate

the tissues in a longitudinal plane. The blades actually are working

along the line of the digital nerve, maximizing exposure of the nerve

while minimizing the

chance of accidental laceration (Fig. 5-42; see Fig. 5-40).

|

|

Figure 5-41

Expose the flexor tendons in a longitudinal fashion. The digital nerves lie lateral to the tendons. Maintain the A2 and A4 pulleys. |

|

|

Figure 5-42 Identify the neurovascular bundles and preserve them.

|

the fibrous flexor sheath and the digital nerves and vessels. (In

practice, it seldom is necessary to go this deep; surgery on the

osseous structures usually is safer through a midlateral or dorsal

incision [Fig. 5-43].)

|

|

Figure 5-43 (A)

Incision for the midlateral approach to the finger. The incision lies between the proper digital nerve, which runs toward the palm, and its dorsal branch. The incision also can be made with the finger flexed; connect the dorsal portions of the interphalangeal creases (inset). (B) Lateral view of the anatomy of the finger. Note the division of the proper (common) digital nerve into dorsal and palmar branches, the relationship of the palmar division of the nerve to the flexor tendon sheath, and the insertion of the lumbrical and interossei muscles into the hood mechanism. |

tendons, and incising the periosteum from the volar surface of the bone

lead to adhesions within the fibrous flexor sheath. It is very

important to note that the consequences of this will be the loss of

full function of the finger. Therefore, every effort should be made to

avoid this at all costs.

at too acute an angle, and skin sutures should be meticulous to ensure

closure. Skin flaps should be thick enough to avoid skin necrosis (see Fig. 5-39). The tourniquet should be removed and hemostasis secured before closure is undertaken.

eventually joining the curved incision parallel to the thenar crease

that is used for exposure of the structures of the palm, volar surface

of the wrist, and anterior surface of the forearm. The key to making

these incisions is to avoid crossing flexion creases at 90°, thus

preventing the development of flexion contractures, and to leave skin

flaps with substantial corners (see Fig. 5-39).

flexor tendons and digital nerves in the fingers. It affords access to

the neurovascular bundle on the incised side of the finger; at the same

time, it is difficult to extend into the palm. Its uses include the

following:

-

Open reduction and stabilization of phalangeal fractures

-

Exposure of the fibrous flexor sheath and its contents

-

Exposure of the neurovascular bundle

the arm stretched out on an arm board. Good lighting and a good

exsanguinating bandage and tourniquet are essential (see Fig. 5-13).

are the key to this skin incision. They extend around the medial and

lateral surfaces of the fingers and end slightly nearer the dorsal than

the volar surface of the finger.

or if it is struck in full extension. If so, the surgical landmark for

the skin incision is the junction between the wrinkled dorsal and the

smooth volar skin on the side of the finger (see Fig. 5-43).

the finger, starting at the most dorsal point of the proximal finger

crease. Continue cutting distally to the distal interphalangeal joint,

passing just dorsal to the dorsal end of the flexor skin crease. Extend

the incision farther distally toward the lateral end of the fingernail.

The incision actually is dorsolateral rather than truly lateral (see Fig. 5-43). Alternatively, flex the finger and make an incision connecting dorsal end points of the interphalangeal crease.

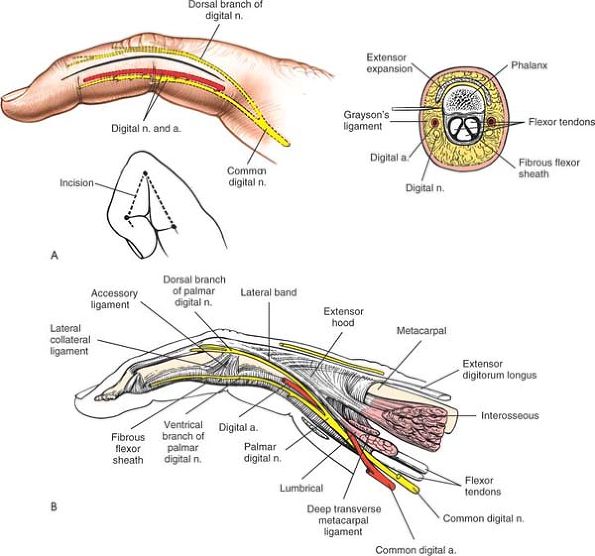

intermuscular interval is developed. The nerve supply to the finger

comes mainly from two sources, the dorsal digital nerves and the volar,

or palmar, digital nerves. Because the skin incision marks the division

between these two supplies, it causes no significant areas of

hypoesthesia.

flap in line with the skin incision. The fat over the proximal

interphalangeal joint is quite thin; take care not to incise the joint

itself. Continue the dissection toward the midline of the finger,

angling slightly in a volar direction. The main neuromuscular bundles

lie in the volar flap (Fig. 5-44).

|

|

Figure 5-44 Develop the skin flap down to the flexor sheath, maintaining the neurovascular bundle in the volar flap.

|

|

|

Figure 5-45 Incise the flexor sheath longitudinally to reveal the tendons.

|

|

|

Figure 5-46

By longitudinal dissection, the neurovascular structures are revealed within the volar flap. Careful dissection of the flexor sheath can expose the entire palmar aspect of the bundle. |

in danger if the skin incision and approach drift too far in a volar

direction. This approach always should begin just dorsal to the end of

the interphalangeal creases. If the approach does begin at this site,

the danger to the palmar digital nerve will be diminished (see Fig. 5-43A).

expose the neurovascular bundle on the opposite side. Note that the

exposure gained is not as good as that offered by a zigzag volar

approach.

key to the treatment and prognosis of flexor tendon injuries. Nowhere

else in the body are the links between anatomy, pathology, and

treatment illustrated so clearly. The structure of the tendons, their

blood supply, and their special relationship to other structures all

relate to the pathogenesis of injury and repair.

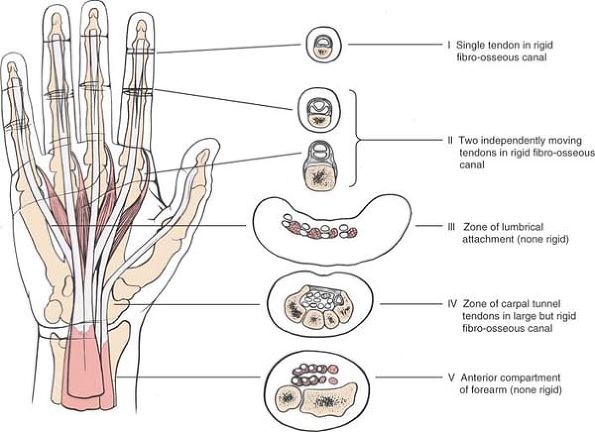

five zones, each of which is separated from the others by anatomic

landmarks. The zones all must be treated differently in cases of tendon

laceration. We shall consider the anatomy from the proximal to the

distal aspect, from zone 5 to zone 1, as devised by Milford (Fig. 5-47).19

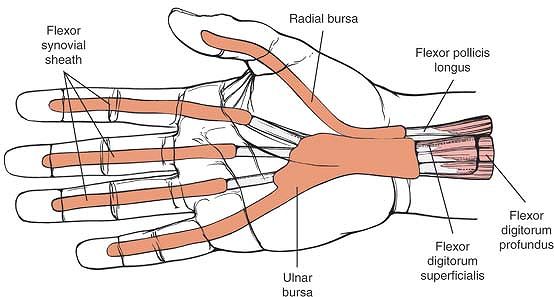

At that point, nine distinct tendons run into the hand toward the

digits. Each finger has two tendons, one each from the flexor digitorum

superficialis muscle and the flexor digitorum profundus muscle. The

thumb has one long flexor, the flexor pollicis longus.

but are surrounded by a synovial sheath in the distal part of the

forearm. Tendon repairs carried out in this area generally are

successful, and independent finger flexion usually returns.

carpal tunnel. All the tendons remain in a common synovial sheath

throughout the carpal tunnel.

prognosis, but not as good as the prognosis of those carried out in

zone 5, because the tendons are enclosed in a fibro-osseous tunnel. The

tunnel must be opened for repairs, and adhesions may form after surgery.

flexor digitorum profundus tendons traverse the palm, a lumbrical

muscle arises from each tendon. The radial two lumbricals arise from a

single head, from the radial side of the profundus tendons to the index

and middle fingers. The ulnar two lumbricals arise from two heads, from

the adjacent sides of the profundus tendons between which they lie. The

tendons of the lumbricals pass along the radial sides of the

metacarpophalangeal joints before they insert into the dorsal

expansion. They pass volar to the axes of the metacarpophalangeal

joints; thus, they act as flexors of those joints, even as they extend

the interphalangeal joints (see Fig. 5-34).

to the lumbrical muscles. Most surgeons do not recommend repairing the

lumbricals; the increased tension on the muscles caused by the repair

produces fixed flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints and limited

flexion at the interphalangeal joints, resulting in an intrinsic plus

hand.

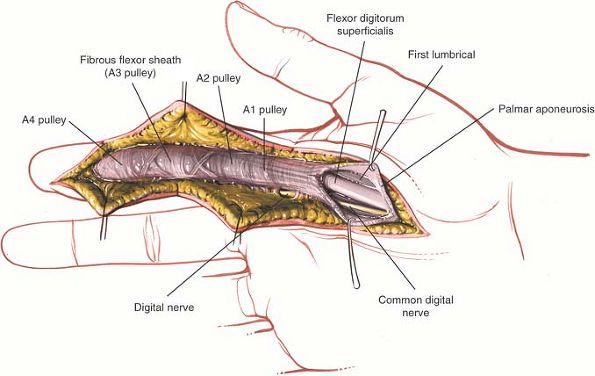

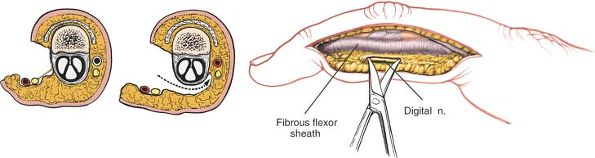

tendons for each finger run together in a common fibro-osseous sheath.

|

|

Figure 5-47 The five zones of the wrist and hand (according to Milford).

|

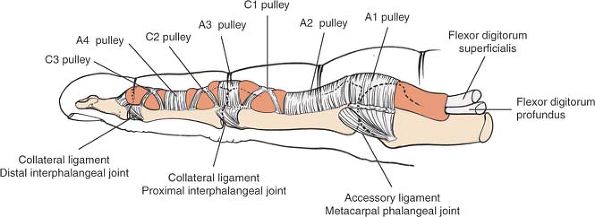

(the distal palmar crease) to the distal phalanges. They are attached

to the underlying bone and prevent the tendons from bowstringing.

They act as pulleys, directing the sliding movement of the tendons.

There are two types: annular and cruciate. Annular pulleys are composed

of a single fibrous band (ring); cruciate pulleys have two crossing

fibrous strands (cross). Annular pulleys act much like the rings on a

fishing rod. Without the ring, the fishing line would pull away from

the rod as it bends. This effect is known as bow-stringing; in human

terms, it results in the loss of range of movement and power in the

affected finger. Annular pulleys include the following:

-

The A1 pulley, which overlies the metacarpophalangeal joint. It is incised during trigger finger release.

-

The A2 pulley, which overlies the

proximal end of the proximal phalanx. It must be preserved (if at all

possible) to prevent bowstringing. -

The A3 pulley, which lies over the proximal interphalangeal joint.

-

The A4 pulley, which is located about the middle of the middle phalanx. It must be preserved to prevent bowstringing.

-

The C1 pulley, which is located over the middle of the proximal phalanx

-

The C2 pulley, which is located over the proximal end of the middle phalanx

-

The C3 pulley, which is located over the distal end of the middle phalanx

superficialis tendon on top of the profundus tendon. Over the proximal

phalanx, the superficialis

tendon

divides into halves, which spiral around the profundus tendon, meeting

on its deep surface and forming a partial decussation (chiasma). The

two then run as one tendon underneath the profundus tendon before

attaching to the base of the middle phalanx. Thus, the superficialis

tendon actually provides part of the bed on which the profundus tendon

runs. Distal to the attachment of the superficialis tendon, the

profundus tendon inserts into the base of the terminal phalanx (see Fig. 5-64).

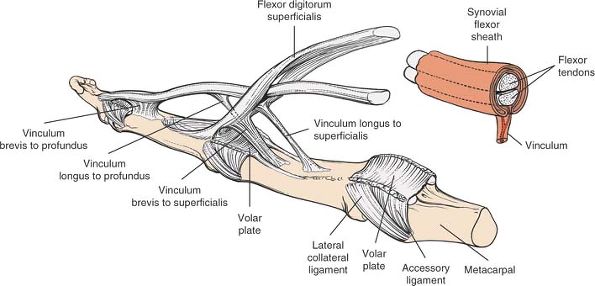

Within the fibro-osseous sheath, the nutrition of the flexor tendons is

provided for by blood vessels that enter the tendons from synovial

folds called vincula (Fig. 5-49).

|

|

Figure 5-48

The annular and cruciate ligaments of the flexor tendon sheath, lateral view. Note the relationship of the pulleys to the skin creases and joint lines. |

|

|

Figure 5-49

The vincula longa and brevia are main blood supplies to the flexor tendons. Note the relationship of the vincula to the flexor tendon synovial sheath (inset). |

after lacerations in zone 2, mainly because the flexor tendons are

enclosed within a nondistensible fibro-osseous canal, and also because,

for full function, the tendons must run over each other. It is

important to remember that any adhesion between the two can cause

malfunction of the involved finger.

superficialis tendon. Although the profundus tendon still is enclosed

tightly within a fibro-osseous sheath here, it runs alone. Therefore,

the prognosis for the repair of lacerations in this zone is better than

that for zone 2, although not as good as that for zones 3, 4, and 5.

Each tendon receives its blood supply from arteries that arise from the

palmar surface of the phalanges. These vessels are encased in the

vinculum (mesotenon). Two vincula supply each tendon, as follows:

-

Profundus tendon.

-

The short vinculum runs to the tendon close to its insertion onto the distal phalanx.

-

The long vinculum passes to the tendon from between the halves of the superficialis tendon at the level of the proximal phalanx.

-

-

Superficialis tendon.

-

The short vinculum runs to the tendon near its attachment onto the middle phalanx.

-

The long vinculum is a double vinculum, passing to each half of the tendon from the palmar surface of the proximal phalanx.

-

that this classic arrangement does not always hold true. The long

vincula to both tendons may be absent in the long or ring fingers. When

they are present, the long vinculum to the superficialis tendon may

attach to either or both of its slips, and the long vinculum to the

profundus tendon may arise at the level of the insertion of the

superficialis tendon.22

tendons are explored within their sheaths. The vincula should be

preserved, if possible, to preserve the blood supply to the tendon.

aspects of the flexor tendons are largely avascular; their nutrition

may be derived from synovial fluid. Therefore, sutures placed in the

volar aspects of the tendons do not interfere materially with the blood

supply to the tendons themselves.23

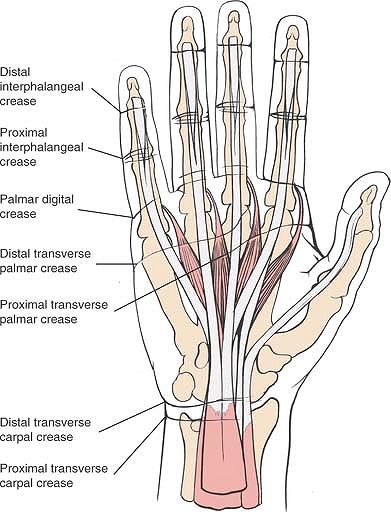

creases, all of which are situated where the fascia attaches to the

skin. There are four major creases: the distal palmar crease

corresponds roughly to the palmar location of the metacarpophalangeal

joints and the location of the proximal (A1) pulley, the palmar digital

crease marks the palmar location of the A2 pulley, the proximal

interphalangeal crease marks the proximal interphalangeal joint, and

the thenar crease outlines the thenar eminence (see Figs. 5-37, 5-47, and 5-48).

two sources: the volar aspect is supplied by the volar digital nerves,

and the dorsal aspect is innervated by the dorsal nerves of the radial

and ulnar nerves, as well as by the dorsal contribution from the volar

digital nerves for the distal 1½ phalanges of the index, long, and ring

fingers. The dorsa of the thumb and small finger are served exclusively

by the radial and ulnar nerves, respectively. Because of this anatomic

arrangement, the midlateral approach to the flexor sheath does not

cause skin denervation (see Fig. 5-43).

It also avoids damaging the dorsal blood supply to the bone’s proximal

half, as well as the superficial branch of the radial nerve. It does

pose a threat to the radial artery, however, which is close to the

operative field. It leaves a more cosmetic scar than does the dorsal

approach, and its uses include the following:

-

Bone grafting for nonunion of the scaphoid

-

Excision of the proximal third of the scaphoid

-

Excision of the radial styloid, either alone or combined with one of the above procedures

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

fractures of the scaphoid. In such cases this approach frequently is

combined with the dorsolateral approach to the scaphoid.

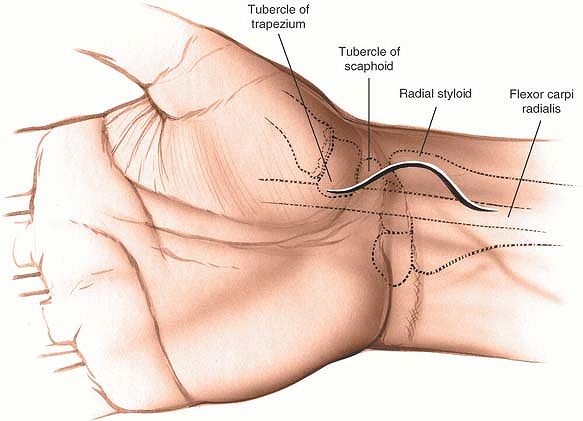

muscle lies radial to the palmaris longus muscle at the level of the

wrist. It crosses the scaphoid before inserting into the base of the

second and third metacarpal just on the ulnar side of the radial pulse.

aspect of the wrist, about 2 to 3 cm long. Base it on the tuberosity of

the scaphoid and extend it proximally between the tendon of the flexor

carpi radialis muscle and the radial artery (Fig. 5-50).

|

|

Figure 5-50

Incision for the volar approach to the scaphoid. Base the incision on the tuberosity of the scaphoid and extend it proximally and distally. The proximal extension is between the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis and the radial artery. |

mobilized is the flexor carpi radialis (which is supplied by the median

nerve).

Retract the radial artery and lateral skin flap to the lateral side.

Identify the tendon of the flexor carpi radialis muscle and trace it

distally, incising that portion of the flexor retinaculum that lies

superficial to it. After the tendon has been freed from its tunnel in

the flexor retinaculum, retract it medially to expose the volar aspect

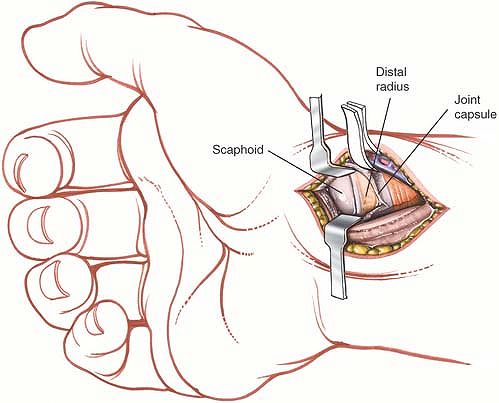

of the radial side of the wrist joint (Fig. 5-52).

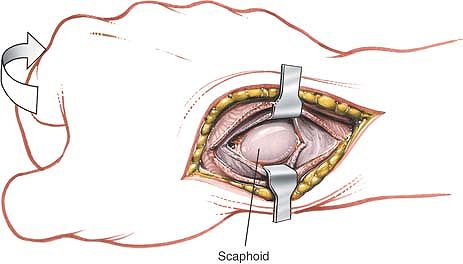

anterior area of bone is nonarticular. To gain the best view of the

proximal third of the bone, place the wrist in marked dorsiflexion (Fig. 5-53).

|

|

Figure 5-51 Incise the deep fascia between the radial artery and the flexor carpi radialis.

|

|

|

Figure 5-52

Retract the radial artery and skin flap laterally and the flexor carpi radialis medially to expose the volar aspect of the radial side of the wrist joint capsule. |

|

|

Figure 5-53 Incise the joint capsule. Dorsiflex the wrist to gain exposure of the proximal articular third of the bone.

|

to the lateral border of the wound and can be incised accidentally at

any time during the dissection. Therefore, it must be identified early

in the procedure.

extent. Proximally, extend the skin incision along the line of the

flexor carpi radialis muscle. Identify the distal border of the

pronator quadratus muscle and elevate it gently from the underlying

bone. This will create adequate exposure of the distal end of the

radius, allowing a bone graft to be taken from this site. Adequate

exposure also will be obtained to allow excision of the radial styloid,

if this is indicated.

dorsiflexion of the wrist. This will expose the proximal pole of the

scaphoid, which is the site of most cases of nonunion. If the location

of the fracture is not completely clear, place a small, radiopaque mark

at the operative site and carry out a radiographic examination on the

operating table. Bone grafting can be carried out adequately with this

exposure, but the insertion of a screw may require a combined dorsal

and volar approach to the scaphoid.25

exposure of the scaphoid bone. Its major drawback is that it endangers

the superficial branch of the radial nerve, and it also may interfere

with the dorsal blood supply of the scaphoid.26 Its uses include the following:

-

Bone grafting for nonunion

-

Excision of the proximal fragment of a nonunited scaphoid

-

Excision of the radial styloid in combination with either of the two above procedures

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

fractures of the scaphoid. When this approach is used for this

indication, it is frequently combined with a volar approach to the

scaphoid.25

the arm extended on an arm board. Pronate the forearm to expose the

dorsoradial aspect of the wrist, and apply an exsanguinating bandage

and tourniquet (see Fig. 5-1).

|

|

Figure 5-54

Incision for dorsolateral exposure of the scaphoid. Make a gently curved S-shaped incision centered over the snuff-box. The superficial branch of the radial nerve crosses directly beneath the incision. |

is truly lateral when the hand is in the anatomic position. Palpate it

in this position and then pronate the arm, keeping a finger on the

styloid process.

small depression that is located immediately distal and slightly dorsal

to the radial styloid process. The scaphoid lies in the floor of the

snuff-box. Ulnar deviation of the wrist causes the scaphoid to slide

out from under the radial styloid process, and it becomes palpable. The

radial pulse is palpable in the floor of the snuffbox, just on top of

the scaphoid.

the snuff-box. The cut should extend from the base of the first

metacarpal to a point about 3 cm above the snuff-box (Fig. 5-54).

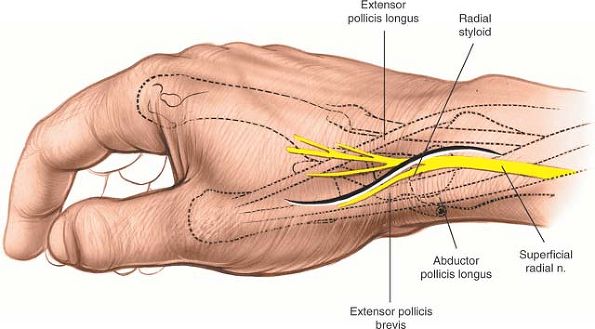

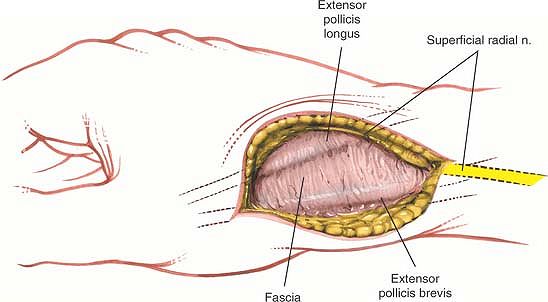

of dissection falls between the tendons of the extensor pollicis longus

and extensor pollicis brevis muscles, both of which are supplied by the

posterior interosseous nerve. Because both muscles receive their nerve

supply well proximal to this dissection, using this plane does not

cause denervation.

To confirm their identity, pull on the tendons and observe their action

on the thumb. Open the fascia between the two tendons, taking care not

to cut the sensory branch of the superficial radial nerve, which lies

superficial to the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle. The

radial nerve usually has divided into two or more branches at this

level. Both branches cross the interval between the tendons of the

extensor pollicis brevis and the extensor pollicis longus, lying

superficial to the tendons. Their course is variable, and they must be

sought and preserved during superficial dissection (see Figs. 5-54 and 5-55).

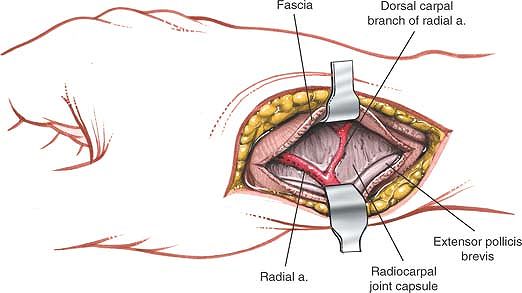

pollicis longus dorsally and toward the ulna, and the extensor pollicis

brevis ventrally. Identify the radial artery as it traverses the

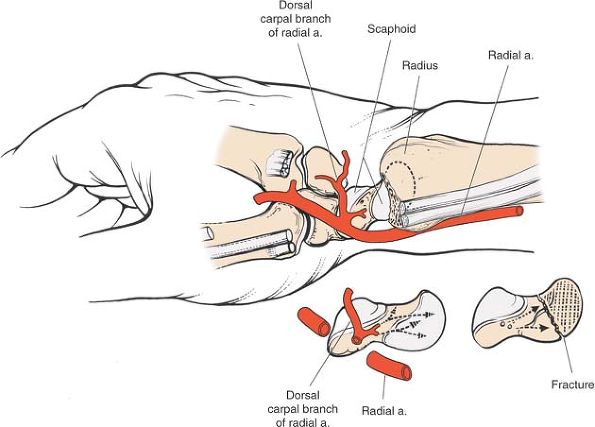

inferior margin of the wound, lying on the bone (Fig. 5-56).

Find the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis longus muscle as it lies

on the dorsal aspect of the wrist joint. Mobilize it and retract it in

a dorsal and ulnar direction, together with the tendon of the extensor

pollicis longus muscle, to expose the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist

joint.

|

|

Figure 5-55

Identify the superficial branch of the radial nerve and retract it with the dorsal skin flap. Identify the tendons of the extensor pollicis longus dorsally and the extensor pollicis brevis ventrally. Incise the fascia between the tendons. |

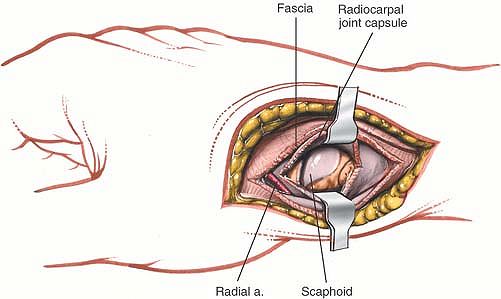

Reflect the capsule dorsally and in a volar direction to expose the

articulation between the distal end of the radius and the proximal end

of the scaphoid. The radial artery retracts radially and in a volar

direction with the joint capsule.

Try to preserve as much soft-tissue attachments to the bone as

possible. Modern aiming guides have substantially reduced the need for

radial dissection in open reduction and internal fixation of scaphoid

fractures.

is at risk during this exposure. Because it lies directly over the

tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle, it is extremely easy to

cut as the tendon is mobilized. Incising the nerve may produce a

troublesome neuroma, as well as an awkward (although not handicapping)

area of hypoesthesia on the dorsal aspect of the hand.

|

|

Figure 5-56

Retract the extensor pollicis longus dorsally and the extensor pollicis brevis ventrally. Identify the radial artery and its dorsal carpal branch, taking care to preserve the arterial branch. |

|

|

Figure 5-57 Incise the joint capsule. The scaphoid is exposed.

|

|

|

Figure 5-58 Place the wrist in ulnar deviation to expose the proximal third of the scaphoid in its entirety.

|

|

|

Figure 5-59

Blood supply to the scaphoid. Most branches enter the scaphoid from the dorsal aspect. These branches must be preserved to prevent necrosis of its proximal fragment. |

morbidity. They cause an enormous loss of time from work and can

produce permanent deficits in hand function. Until recently, the

availability of more prompt medical care and the administration of

antibiotics had caused a dramatic decrease in the incidence of major

hand infections; however, the intravenous and subcutaneous use of

narcotics among drug addicts has increased, reintroducing serious hand

infections to the field of surgery.

-

Accurate localization of the infection.

Each particular infection has characteristic physical signs, according

to the anatomy of the particular compartment that is infected. -

Timing of the operation.

The timing of surgical drainage is critical to the outcome of surgical

treatment. If an infection is incised too early, the surgeon may incise

an area of cellulitis and actually cause the infection to spread. In

contrast, if pus is left in the hand too long, particularly around the

tendon, it may induce irreversible changes in the structures it

surrounds.

difficult to determine. In the body, the cardinal physical sign of an

abscess is the presence of a fluctuant mass within an area of

inflammation; however, because there often is only a small amount of

pus present in the hand, an abscess there can be hard to find. In

addition, pus frequently is found in tissues that contain fat. At body

temperature, fat itself is fluctuant, further complicating the physical

diagnosis of an abscess. Nevertheless, some guidelines for the

detection of pus do exist:

-

Pus may be seen subcutaneously.

-

The longer an infection has been present,

the more likely it is that pus will be present. Infections of less than

24 hours’ duration are unlikely to have developed pus. -

Classically, if the patient cannot sleep at night because of pain in the hand, pus probably has formed.

-

If slight passive extension of the finger

produces pain along the finger and in the palm, the tendon sheath is

likely to be infected; it should be explored to drain the pus.

one of the four cardinal signs of acute suppurative tenosynovitis

described by Kanavel.27 The other three follow below:

-

Swelling around the tendon sheath

-

Tenderness to palpation

-

Flexion deformity of the affected finger

determine whether there is pus in the hand. If doubt exists, elevate

the arm and treat the patient with intravenous antibiotics and warm

soaks, reexamining him or her at frequent intervals. If signs of

inflammation diminish rapidly, avoid surgery.

-

Use a general anesthetic or a distal

nerve block. Injecting a local anesthetic at the site of infection is

ineffective and actually may spread the infection within fascial planes. -

Use a tourniquet. The arm should not be

exsanguinated with a bandage, to avoid spreading the infection by

mechanical compression. The arm should be elevated for 3 minutes before

the tourniquet is applied. -

Perfect lighting is critical for all

explorations of pus in the hand. All relevant neurovascular bundles

must be identified to ensure their preservation. -

Draining abscesses of the hand is not

like draining abscesses anywhere else in the body. Boldly incising an

abscess space without approaching it carefully is to be condemned. -

Leave all wounds open after incision.

-

Immobilize the hand in the functional

position after surgery by applying a dorsal or volar splint, or both,

with the metacarpophalangeal joints at 80° of flexion and the proximal

and distal interphalangeal joints at 10° of flexion. At this position,

the collateral ligaments of the metacarpophalangeal, proximal

interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints are at their maximum

length and will not develop contractures during immobilization. -

Elevate the arm postoperatively. Continue

administering intravenous antibiotics until signs of inflammation begin

to diminish. Mobilize the affected part as soon as signs of

inflammation subside. Begin extensive rehabilitation, which may last

several months.

-

Paronychia

-

Pulp space (felon)

-

Web space

-

Tendon sheath

-

Deep palmar area

-

Lateral space (thenar space)

-

Medial space (midpalmar space)

-

-

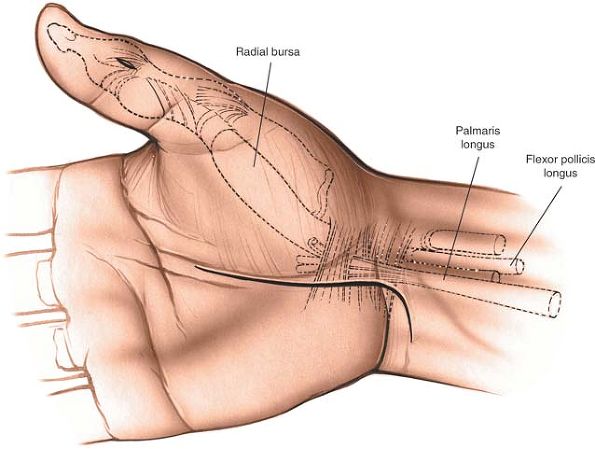

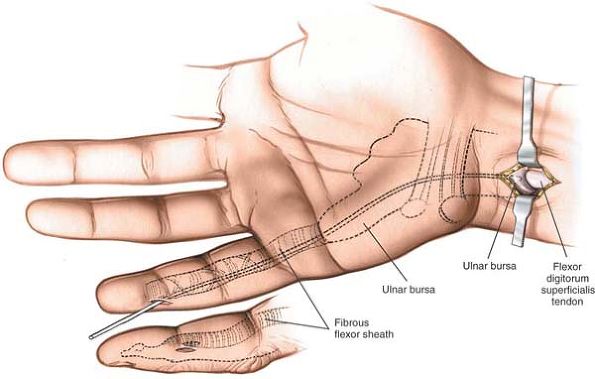

Radial bursa

-

Ulnar bursa

Hairdressers often are affected because hair from their clients may

become embedded between the cuticle and the bony nail. Tearing the

cuticle to remove a “hangnail” probably is the most common cause of

this infection.

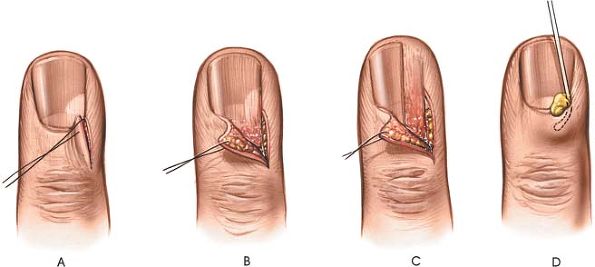

cuticle. The paronychia may occur on either side or it may lift the

whole of the cuticle upward. It even may extend underneath the nail.

supply of the skin in this region is derived from cutaneous nerves that

overlap one another considerably. No area of skin becomes denervated.

cuticle and the nail. If pus extends under the nail, excise either one

corner of the base of the nail or half of the nail itself, depending on

how it has been undermined and lifted off the nail bed (see Fig. 5-60B,C). Occasionally, a nick into the soft-tissue cuticle parallel with the nail will release the pus (see Fig. 5-60D).

|

|

Figure 5-60 (A through D:) Incisions for the evacuation of pus at the base of the nail (paronychia).

|

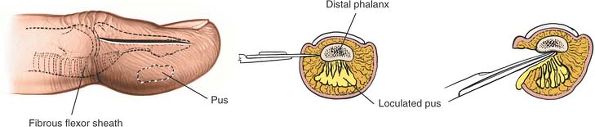

infections that most often require surgical drainage. Infection is

usually caused by a penetrating injury to the pulp, an injury that may

be quite trivial in itself. Superficial infections cause skin necrosis

and point early, usually on the volar aspect of the pulp. Deeper

infections are more likely to cause osteomyelitis of the underlying

distal phalanx, a condition that is known as a felon or whitlow.

-

If the abscess is pointing in a volar

direction in the distal pulp of the finger, as it commonly is, make a

small incision on the lateral side of the volar surface and enter the

abscess cavity obliquely. Midline incisions may produce painful scars. -

If the abscess is deep, the surgery described below may be necessary.

terminal phalanx of the finger, extending to the tip of the finger

close to the nail. The incision should not extend proximally to the

distal interphalangeal joint; more proximal incisions may damage the

digital nerve, causing a painful neuroma, or they may contaminate the

joint with purulent material.

It should not extend distally beyond the distal corner of the nail.

Avoid the ulnar aspect of the thumb and the radial aspect of the index

and long fingers to avoid creating a scar that interferes with pinch.

skin incision lies between skin that is supplied by the dorsal

cutaneous nerve and skin that is supplied by branches of the volar

digital nerves.

|

|

Figure 5-61 Incision for drainage of pulp space infection (felon). The septa must be cut to ensure appropriate drainage.

|

fibrous septa that connect the distal phalanx with the volar skin,

creating loculi. The infection easily can invade several of these

loculi. To ensure that all pockets of infection are drained, deepen the

skin incision transversely across the pulp of the finger, remaining on

the volar aspect of the terminal phalanx, until the skin of the

opposite side of the finger is reached. Do not penetrate this skin (see

Fig. 5-61). Now, bring the scalpel blade

distally, detaching the origins of the fibrous septa from the bone.

Proximally, take care not to extend the dissection beyond a point 1 cm

distal to the distal interphalangeal crease; otherwise, the flexor

tendon sheath may be damaged and infection introduced into it.

damaged if the skin incision drifts too far proximally. Painful

neuromas can result without an appreciable area of hyperesthesia on the

finger.

skin make this an ideal site for loculation of pus. Take care to open

all the loculi so that adequate drainage takes place. Unsuccessful

treatment of a deep abscess may result in osteomyelitis of the distal

phalanx.

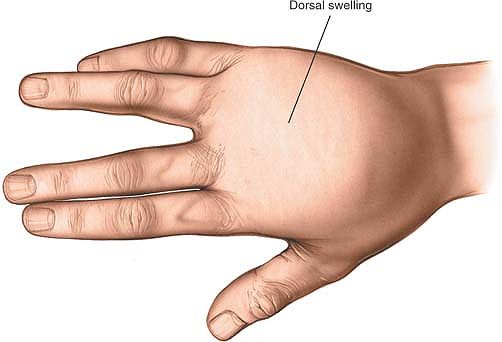

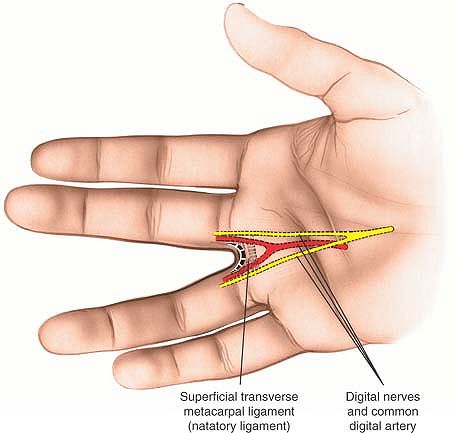

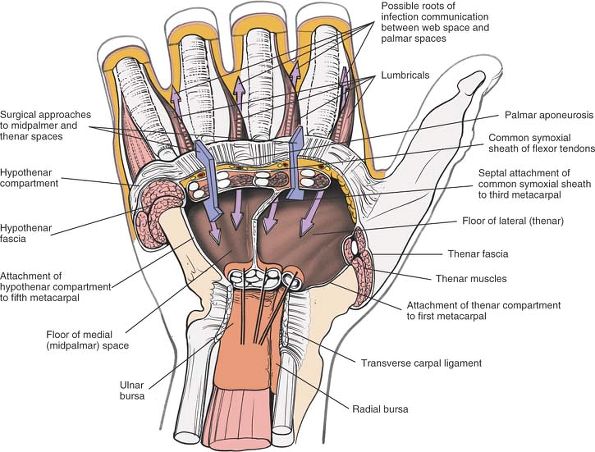

four webs of the palm, are quite common. The abscess usually points

dorsally, because the skin on the dorsal surface of the web is thinner

than the skin on the palmar surface. Characteristically, a large amount

of edema appears on the dorsum of the hand, and the two fingers of the

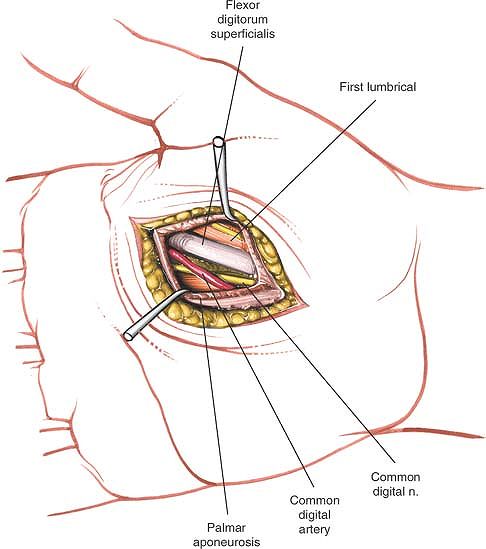

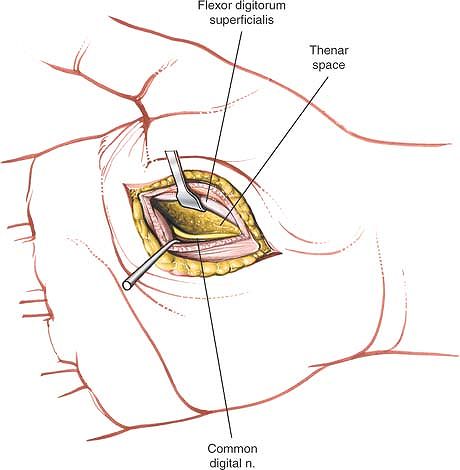

affected web are spread farther apart than normal (Fig. 5-62).

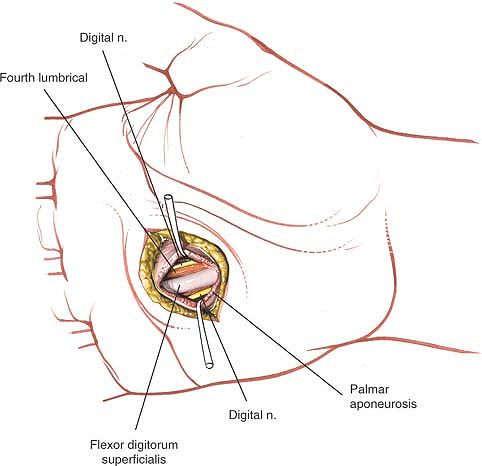

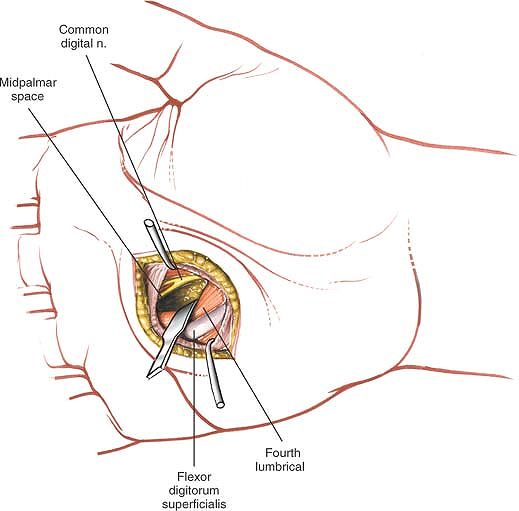

lumbrical muscles into the palm; therefore, a neglected web space

infection can cause a more extensive infection by spreading up the

lumbrical canal and into the palm.

the arm on an arm board. Use a general anesthetic or an axillary or

brachial block, then raise the arm for 3 minutes before inflating an

arm tourniquet (see Fig. 5-13).

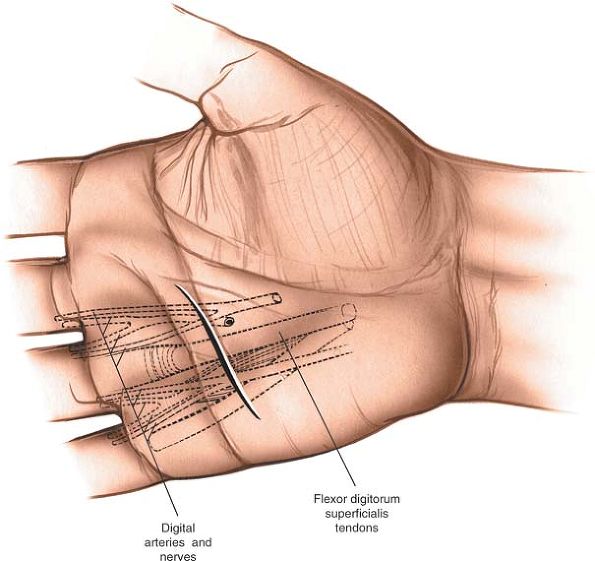

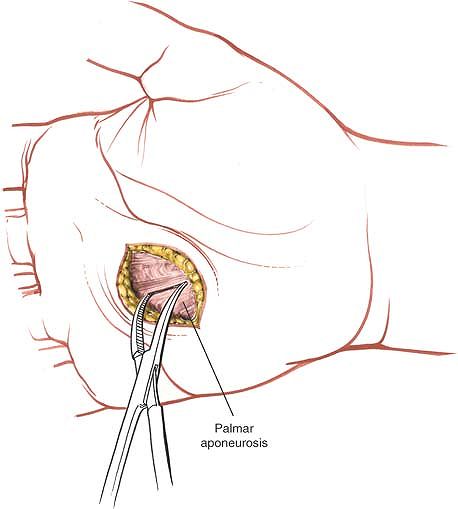

the palm, following the contour of the web space about 5 mm proximal to

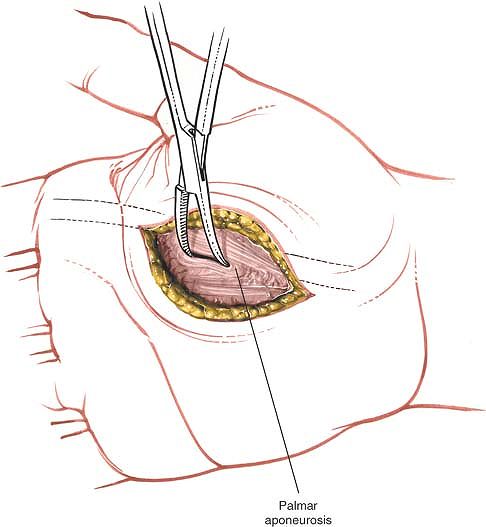

it (Fig. 5-63).

|

|

Figure 5-62

Web space infection. A large amount of edema usually appears on the dorsum of the hand, and the two fingers of the affected web space are spread farther apart than normal. |

The digital nerves and vessels lie immediately under the incision and

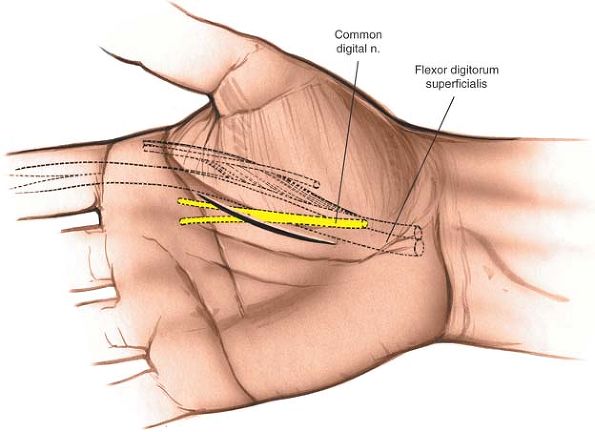

may be damaged if the cut is too deep, mainly because the dissection is