The Forearm

differ significantly. The ulna has a subcutaneous border that extends

for its entire length; the bone can be reached simply and directly

without endangering other structures. In contrast, the upper two thirds

of the radius are enclosed by a sheath of muscles. All surgery in the

upper third of the radius is complicated further by the posterior

interosseous nerve, which winds spirally around the bone close to, if

not in contact with, its periosteum.

in this chapter, all of which allow for the complete exposure of bone.

In nearly every case, only part of the approach is required. The anterior approach to the radius

is one of the classic extensile approaches, relying on subperiosteal

dissection for protection of the posterior interosseous nerve. The posterior approach to the radius

also makes use of an internervous plane, but still requires

identification and preservation of the posterior interosseous nerve.

The approach to the ulna cuts directly

onto its subcutaneous border. The anatomy of the anterior approach to

the radius, the approach to the ulna, and the anatomy of the posterior

compartment of the forearm are considered separately. Because of the

critical importance of the posterior interosseous nerve, its course is

described in both anatomic sections.

of the radius, exposing the entire length of the bone. Exposing the

proximal third of the radius endangers the posterior interosseous

nerve. By stripping the supinator muscle off the radius subperiosteally

and using it to protect the nerve, however, the anterior approach

avoids this danger. Still, great care must be taken in positioning

retractors, because the nerve actually may touch the bone at the level

of the distal portion of the neck of the radius, opposite the bicipital

tuberosity, and posteriorly placed retractors can compress it against

the bone. The approach first was described by Henry, and his name

usually is associated with it.1

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures2

-

Bone grafting and fixation of fracture nonunions

-

Radial osteotomy

-

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

-

Excision of sequestra in chronic osteomyelitis

-

Anterior exposure of the bicipital tuberosity

-

Treatment of compartment syndrome

entire length of the bone. Ordinarily, only a portion of the approach

is required.

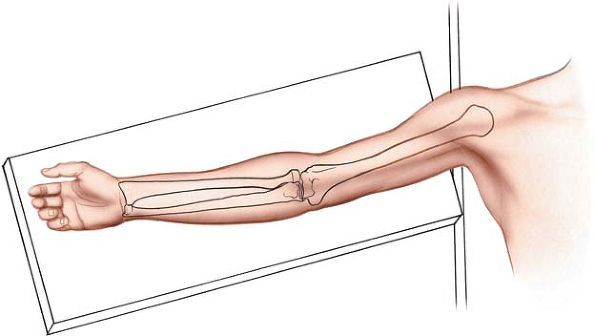

the arm on an arm board. Place a tourniquet on the arm, but do not

exsanguinate it fully before inflating the tourniquet. Venous blood

left in the arm makes the vascular structures easier to identify.

Finally, supinate the forearm (Fig. 4-1).

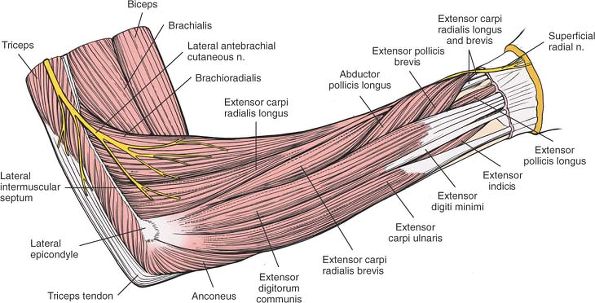

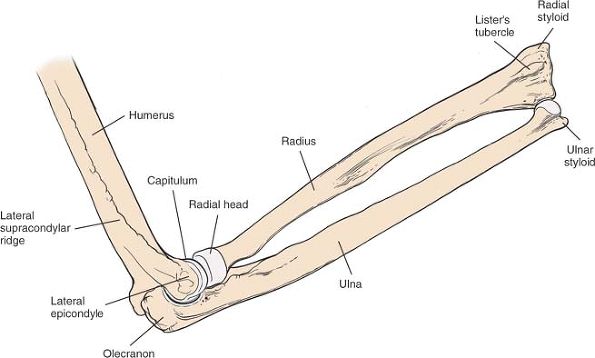

which is a fleshy muscle that arises with the extensor carpi radialis

longus and brevis muscles from the lateral epicondyle of the elbow. The

three muscles form a “mobile wad” of muscle that runs down the lateral

aspect of the supinated forearm.

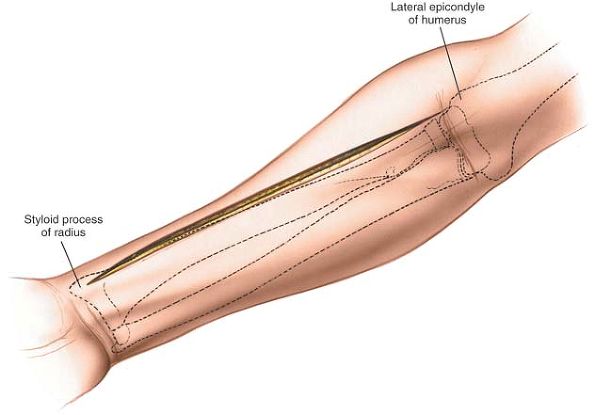

Note that this bony process is truly lateral when the hand is in the

anatomic (supinated) position. The styloid process is the most distal

part of the lateral side of the radius.

of the elbow just lateral to the biceps tendon down to the styloid

process of the radius. The length of the incision depends on the amount

of bone that needs to be exposed (Fig. 4-2).

|

|

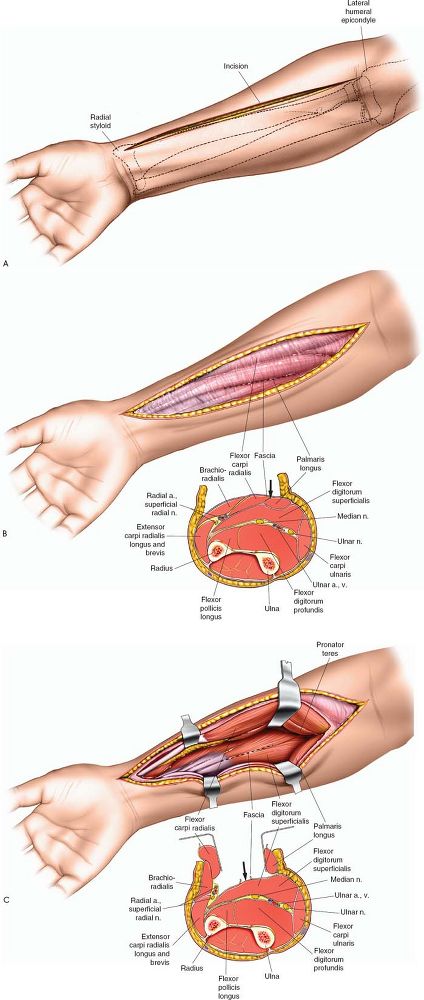

Figure 4-1 Position of the patient on the operating table, for the anterior approach to the radius.

|

|

|

Figure 4-2

Make a straight incision on the anterior part of the forearm, from the flexor crease on the lateral side of the biceps down to the styloid process of the radius. |

|

|

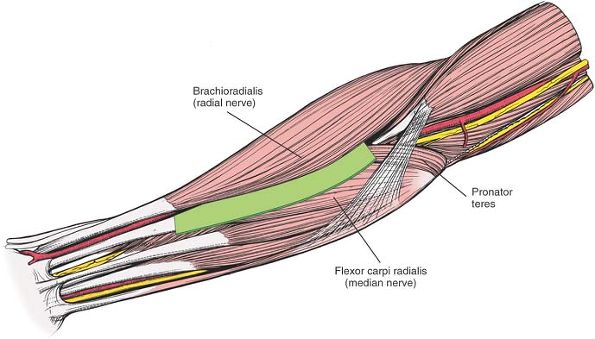

Figure 4-3 Internervous plane. The plane lies between the brachioradialis (radial nerve) and the flexor carpi radialis (median nerve).

|

Proximally, the internervous plane lies between the brachioradialis

muscle, which is innervated by the radial nerve, and the pronator teres

muscle, which is innervated by the median nerve.

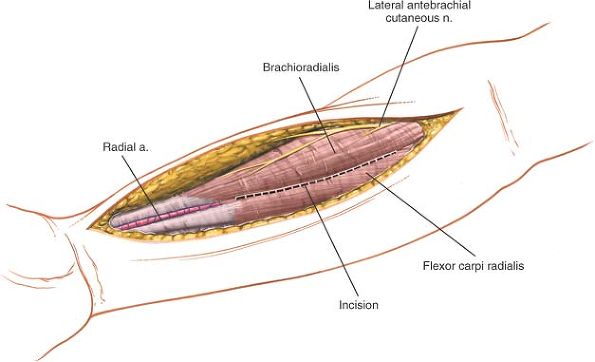

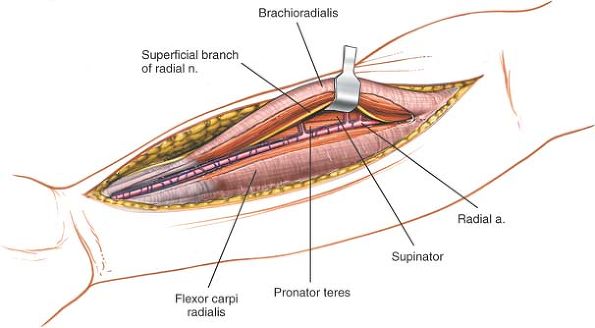

skin incision. Identify the medial border of the brachioradialis as it

runs down the forearm, and develop a plane between it and the flexor

carpi radialis distally. More proximally, the plane lies between the

pronator teres and brachioradialis muscles (Fig. 4-4).

Note that the medial border of the brachioradialis is surprisingly far

across the forearm. At the level of the elbow the brachioradialis

extends almost halfway across the forearm.

the superficial radial nerve running on the undersurface of the

brachioradialis and moving with it. The brachioradialis receives a

number of arterial branches from the radial artery (called the

recurrent radial artery) just below the elbow joint. Ligate this

recurrent leash of vessels (Fig. 4-5). Take

care to ligate these vessels and not avulse them, as avulsion is a

potent cause of postoperative hematoma formation. Many vessels are

present and all will need to be ligated and divided to allow the

brachioradialis to be mobilized laterally.

the middle part of the forearm; therefore, it is quite close to the

medial edge of the wound. It runs with its two venae comitantes, which

remain prominent if the limb is not exsanguinated before the tourniquet

is applied. Often, the artery may have to be mobilized and retracted

medially to achieve adequate exposure of the deeper muscular layer,

particularly at the upper and lower ends of the approach (see Fig. 4-5).

in the forearm, also runs under cover of the brachioradialis muscle.

Preserve the nerve, because damage to it may create a painful neuroma

at the operative site (see Fig. 4-5). It is retracted laterally with the brachioradialis muscle.

|

|

Figure 4-4 Incise the fascia and develop the plane between the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi radialis.

|

|

|

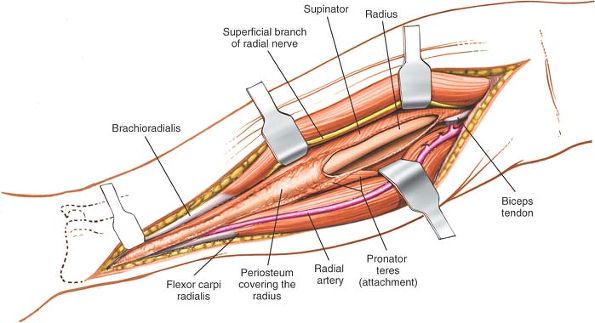

Figure 4-5

A leash of vessels from the radial artery supplies the brachioradialis. The vessels must be ligated to mobilize the brachioradialis laterally. Retract the superficial branch of the radial nerve with the brachioradialis muscle. |

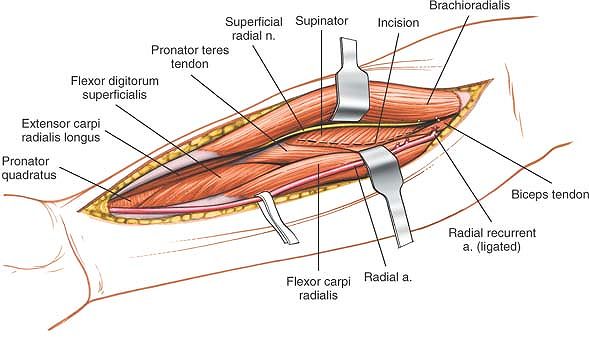

bicipital tuberosity of the radius. Just lateral to the tendon is a

small bursa; incise the bursa to gain access to the proximal part of

the shaft of the radius. Because the radial artery lies superficial and

just medial to the tendon at this point, deepen the wound on the lateral side of the biceps tendon (Fig. 4-6).

supinator muscle, through which the posterior interosseous nerve passes

on its way to the posterior compartment of the forearm.

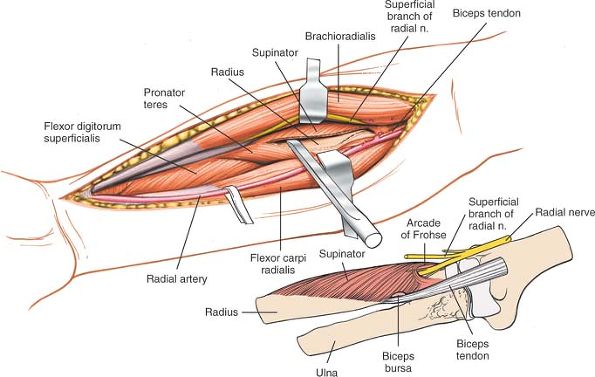

important structure left vulnerable by this approach. To displace the

nerve laterally and posteriorly (away from the surgical area), fully

supinate the forearm, exposing, at the same time, the insertion of the

supinator muscle into the anterior aspect of the radius (Fig. 4-7).

broad insertion. Ensure that the muscle is detached by dividing its

insertion and not by splitting the muscle. Continue subperiosteal

dissection laterally, stripping the muscle off the bone (see Fig. 4-7).

Lateral retraction of the muscle lifts the posterior interosseous nerve

clear of the operative field, but be careful! Excessive traction may

cause a neurapraxia of the nerve, and it recovers very slowly, taking

up to 6 to 9 months. Finally, do not place retractors on the posterior

surface of the radial neck, because they may compress the posterior

interosseous nerve against the bone in patients whose nerve comes into

direct contact with the posterior aspect of the radial neck (about 25%

of all patients).3

|

|

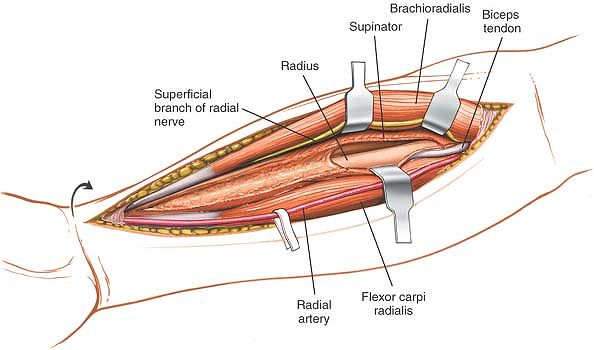

Figure 4-6

Deep to the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi radialis are the supinator muscle, the pronator teres, the flexor digitorum superficialis, and, most distally, the pronator quadratus. |

covered by the pronator teres and flexor digitorum superficialis

muscles. To reach the anterior surface of the bone, pronate the arm so

that the insertion of the pronator teres onto the lateral aspect of the

radius is exposed (Fig. 4-8; see Fig. 4-6).

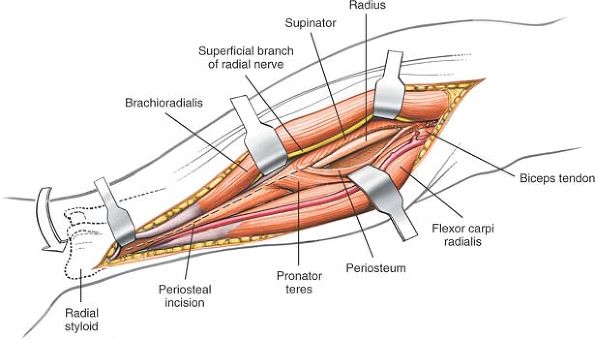

Detach this insertion from the bone and strip the muscle off medially.

Preserve as much soft tissue as you can compatible with accurate

reduction and fixation of the fracture. This maneuver detaches the

origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis from the anterior aspect

of the radius as well (Fig. 4-9).

quadratus, arise from the anterior aspect of the distal third of the

radius. To reach bone, partially supinate the forearm and incise the

periosteum of the lateral aspect of the radius lateral to the pronator

quadratus and the flexor pollicis longus. Then, continue the dissection

distally, retracting the two muscles medially and lifting them off the

radius (Fig. 4-10).

|

|

Figure 4-7

With the patient’s arm in the supinated position, resect the origin of the supinator. Reflect the muscle laterally. Leave the posterior interosseous nerve in the muscle’s substance. The radial nerve enters the supinator through the arcade of Frohse (inset). Turning the forearm upward moves the nerve laterally, away from the operative field. The origin of the supinator muscle is easier to identify if the surgeon stays lateral to the biceps tendon and locates the bursa between it and the supinator. |

|

|

Figure 4-8 Turn the arm downward to identify the pronator teres muscle. Resect it along its insertion on the lateral aspect of the radius.

|

|

|

Figure 4-9 Continue dissection distally to uncover the distal part of the radius. Leave the periosteum intact.

|

|

|

Figure 4-10

With the arm in partial supination, remove the flexor pollicis longus and the pronator quadratus from the bone to expose the entire radius from its proximal to distal end. |

is vulnerable as it winds around the neck of the radius within the

substance of the supinator muscle. The key to ensuring its safety is to

detach correctly the insertion of the supinator muscle from the radius.

The insertion of the muscle is exposed completely only when the arm is

supinated fully. Once the subperiosteal dissection is begun, the nerve

is comparatively safe, but overzealous retraction still can lead to a

neurapraxia (see Figs. 4-7, inset, and 4-13).

runs down the forearm under the brachioradialis muscle. It becomes

vulnerable when the “mobile wad” of three muscles is mobilized and

retracted laterally (see Fig. 4-5). The

superficial radial nerve is vulnerable to neurapraxia if it is

retracted vigorously. Take great care, therefore, when retracting the

nerve and warn your patients preoperatively that temporary paresthesia

in the distribution of the superficial branch of the radial nerve may

occur in the early postoperative phase.

the middle of the forearm under the brachioradialis muscle. It is

vulnerable twice during the anterior approach to the radius:

-

During mobilization of the

brachioradialis. Protection depends on recognizing the artery. Its two

accompanying venae comitantes are the best surgical guide, because the

artery is surprisingly small after a tourniquet has been used (see Fig. 4-5). -

In the proximal end of the wound, as the

artery passes to the medial side of the biceps tendon. Damage to the

artery at that level can be avoided by remaining lateral to the tendon

(see Fig. 4-13).

are a leash of vessels that arise from the radial artery just below the

elbow joint. They consist of two groups, anterior and posterior, which

pass in front of and behind the superficial radial nerve, respectively,

before entering the brachioradialis muscle. They must be ligated to

allow mobilization of both the artery and the nerve (see Figs. 4-9 and 4-12).

entire length of the radius. The approach can be extended distally to

expose the wrist joint.4 Although it can be extended into an anterolateral approach to the elbow and humerus, such extension rarely is required.

(the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor

carpi radialis brevis), which is supplied by the radial nerve, forms

the lateral border of the supinated forearm; and the flexor-pronator

muscles, which are supplied by the median and ulnar nerves, comprise

the rest.

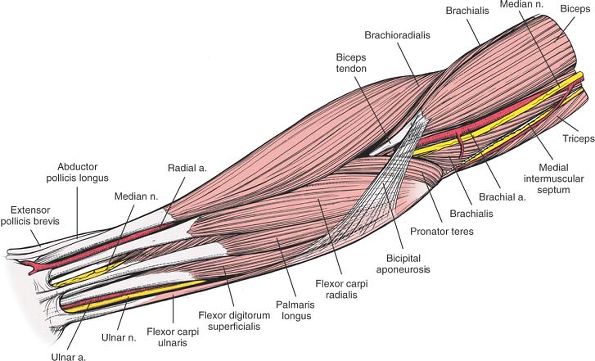

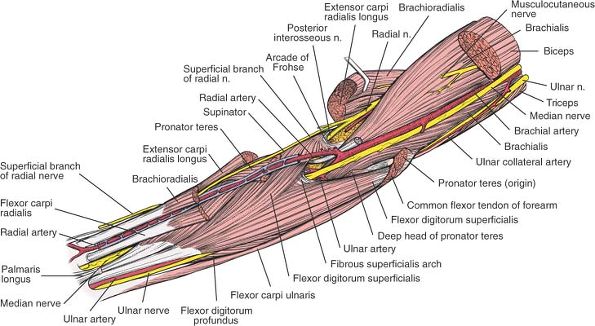

four muscles arise from the common flexor origin on the medial humeral

epicondyle and fan out across the forearm. They are easy to remember by

the following simple maneuver. Place the butt of the opposite hand over

the medial epicondyle, with the palm on the anterior surface of the

forearm: the thumb points in the direction of the pronator teres, the

index finger represents the flexor carpi radialis, the middle finger

represents the palmaris longus, and the ring finger represents the

flexor carpi ulnaris (Figs. 4-11 and 4-12).

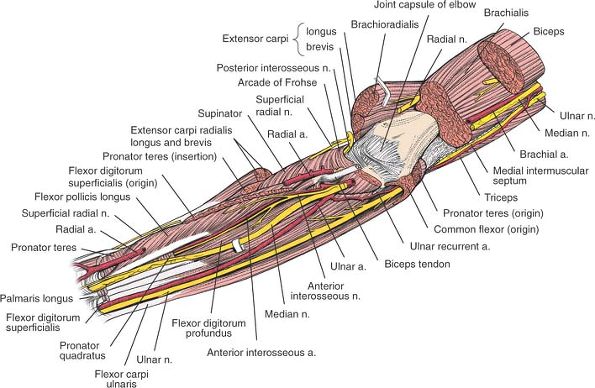

of three muscles: the flexor digitorum profundus, the flexor pollicis

longus, and the pronator quadratus. (A fourth deep muscle, the

supinator, is critical to the surgical anatomy of the area, but is not

strictly a flexor muscle [Fig. 4-14].)

internervous planes that are used in operative approaches:

|

|

Figure 4-11 Superficial layer of the forearm muscles and vessels.

|

|

|

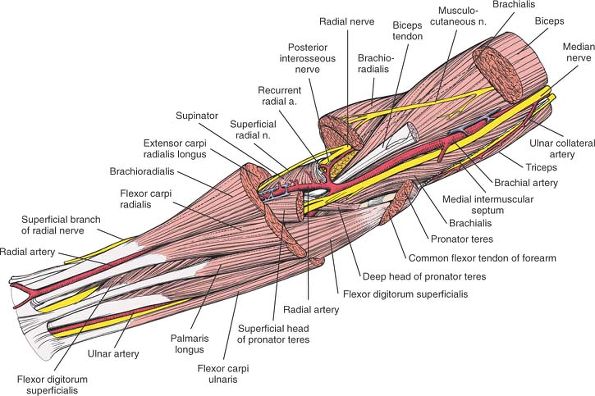

Figure 4-12

The superficial layer of the forearm has been resected, revealing the vessels and nerves. The median nerve pierces the gap between the two heads of the pronator teres. Note the leash of vessels of the radial artery and the recurrent radial artery. |

|

|

Figure 4-13

The middle layer of the forearm, with the superficial branch of the radial nerve. In the proximal part of the wound, the median nerve enters the undersurface of the superficialis. Flexor Carpi Radialis. Origin. Common flexor origin on medial epicondyle of humerus. Insertion. Bases of second and third metacarpals. Action. Flexor and radial deviator of wrist. Nerve supply. Median nerve.

|

|

|

Figure 4-14

The deep layer of the forearm. The ulnar nerve and artery and the median nerve lie on the flexor digitorum profundus. Note the position of the anterior interosseous nerve and artery. |

-

Between the radial and median nerves: a

dissection between the brachioradialis muscle, the most medial of the

three muscles forming the “mobile wad of three” (which is supplied by

the radial nerve), and the flexor carpi radialis and pronator teres

muscles, the most lateral of the flexor-pronator group (which are

supplied by the median nerve; see Fig. 4-3) -

Between the median and ulnar nerves: a

dissection between the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is supplied

by the ulnar nerve) and the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle, the

most medial of the flexor muscles (which is supplied by the median

nerve; see Fig. 5-29) -

Between the ulnar and posterior

interosseous nerves: a dissection between the flexor carpi ulnaris

muscle (which is supplied by the ulnar nerve) and the extensor carpi

ulnaris muscle (which is supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve;

see Fig. 4-21)

approach to the radius, the second exposes the ulnar nerve in the

forearm, and the third is used for exposure of the ulna.

the forearm is relatively simple: the forearm is “framed” by its

nerves. The superficial radial nerve runs

down the radial aspect of the forearm, with the radial artery lying on

its medial side in the distal half of the forearm (see Fig. 4-13). The ulnar nerve

runs down the ulnar side of the forearm, with the ulnar artery lying on

its lateral side in the distal half of the forearm. The median nerve runs down the middle of the forearm (see Fig. 4-14).

are arteries of transit in the forearm; they both are branches of the

brachial artery. Because the brachial artery lies in the middle of the

anterior aspect of the elbow, with the median nerve lying on its medial

side, the ulnar artery and median nerve must cross in the upper

forearm, with the nerve superficial to the artery; this crossing occurs

at the level of the musculotendinous region of the pronator teres

muscle (see Fig. 4-13). The anterior

interosseous nerve (which is a branch of the median nerve) and the

anterior interosseous artery (which is a branch of the common

interosseous artery, which itself is a branch of the ulnar artery) also

run down the middle of the forearm, but deeper than the median nerve

(see Fig. 4-14).

of cleavage in the forearm, the resultant scar may be broad. Making the

incision as a series of gentle curves brings the skin incision closer

to the lines of cleavage in the forearm. Such an incision has the

effect of reducing tension on the subsequent skin repair.

the mobile wad of three muscles (the brachioradialis, extensor carpi

radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis) and the pronator

teres muscle proximally and flexor carpi radialis muscle distally (see Fig. 4-11).

the forearm, is supplied by the radial nerve. All three muscles take

some of their origin from the common extensor origin on the lateral

epicondyle of the humerus (see Fig. 4-13).

the forearm when it is supinated and supinates it when it is pronated.

Therefore, it may act as a deforming force in distal radial fractures

if the forearm is immobilized in either full pronation or full

supination after reduction of the fracture. Its action is one reason

for immobilizing distal radial fractures with the forearm in the

neutral position.

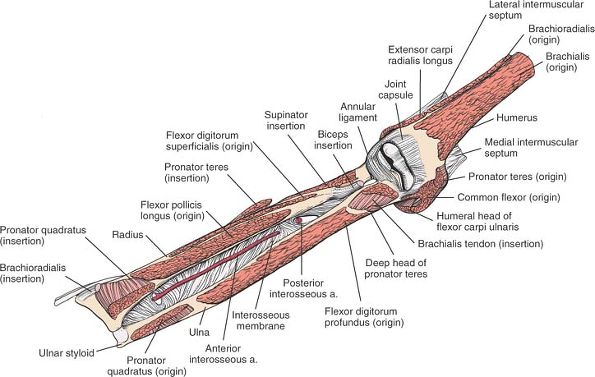

take origin from the distal end of one bone and insert onto the distal

end of another (Fig. 4-15; see Fig. 4-11).

is one of the first muscles to be reinnervated. If the patient

recovering from a high radial nerve palsy is asked to extend the wrist,

the muscle extends with radial deviation, because the balancing muscle,

the extensor carpi ulnaris, is supplied farther distally by a branch

from the posterior interosseous nerve. Reinnervation of the

brachioradialis, however, probably is the best way to diagnose both

clinically and electrically (by electromyographic studies) a recovering

high radial nerve palsy (see Figs. 4-12 and 4-24).

muscle is a wrist extensor that deviates the wrist neither toward the

radius nor toward the ulna. It may be involved in tennis elbow–lateral

epicondylitis.

the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle have been described.

|

|

Figure 4-15

The origins and insertions of the muscles of the forearm. Note the anterior interosseous artery lying on the interosseous membrane. Brachioradialis. Origin. Upper two thirds of lateral supracondylar ridge of humerus. Insertion. Styloid process of radius. Action. Flexor of elbow. Pronator and supinator of forearm. Nerve supply. Radial nerve.

Flexor Digitorum Superficialis. Origin.

Medial epicondyle of humerus, medial ligament of elbow, medial border of coronoid process of ulna, fibrous arch connecting coronoid process of ulna with anterior oblique line of radius. Insertion. Volar aspect of middle phalanges of fingers. Action. Flexor of proximal interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal joints, and wrist joint. Nerve supply. Median nerve. Flexor Pollicis Longus. Origin. Middle part of anterior surface of radius. Insertion. Distal phalanx of thumb. Action. Main flexor of thumb. Nerve supply. Anterior interosseous nerve.

Pronator Quadratus. Origin. Lower fourth of volar surface of ulna. Insertion. Lower fourth of lateral aspect of radius. Action. Weak pronator of forearm. Nerve supply. Anterior interosseous nerve.

Palmaris Longus. Origin. Common flexor origin on humerus. Insertion. Palmar aponeurosis. Action. Weak flexor of wrist. Nerve supply. Median nerve.

Flexor Digitorum Profundus. Origin. Upper three fourths of anterior surface of ulna. Insertion. Distal phalanges of fingers. Action. Flexor of distal interphalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal joints, and wrist joint. Nerve supply. Median and ulnar nerves.

Flexor Carpi Ulnaris. Origin.

From two heads. Humeral head: from common flexor origin on medial epicondyle of humerus. Ulnar head: from medial border of olecranon and upper three fourths of subcutaneous border of ulna. Insertion. Hamate and fifth metacarpal. Action. Flexor and ulnar deviator of wrist. Also weak flexor of elbow. Nerve supply. Ulnar nerve. |

-

The radial artery

originates from the brachial artery in the cubital fossa. Proximally,

it lies just medial to the biceps tendon in a somewhat superficial

position. The radial artery angles across the arm as it descends, lying

on the supinator, the pronator teres, the origin of the flexor pollicis

longus, and the lower part of the anterior surface of the radius, where

it can be palpated easily (see Fig. 4-13). -

The superficial radial nerve

is purely sensory in the forearm. It runs along the lateral side,

crossing the supinator, the pronator teres, and the flexor digitorum

superficialis. Damage to the nerve in the forearm produces an area of

diminished sensation on the dorsoradial aspect of the hand. The most

important problem associated with such damage is not the sensory loss,

however, but the painful neuroma that may result. The nerve runs

lateral to the radial artery when the two are together (see Figs. 4-13 and 4-34).

fully the anterior aspect of the bone. From proximal to distal, they

are as follows:

-

The supinator

-

The pronator teres

-

The flexor digitorum superficialis

-

The flexor pollicis longus

-

The pronator quadratus

muscle, the posterior interosseous nerve, passes through a fibrous arch

known as the arcade of Frohse as it enters the muscle (see Figs. 4-12 and 4-13).5

The arch is formed by the thickened edge of the superficial head of the

supinator. Compression of the nerve at that point produces paralysis or

dysfunction of all the extensor muscles of the forearm, fingers, and

thumb, a lesion that may be incomplete. Compression at the arcade of

Frohse is one of the causes of a posterior interosseous nerve

entrapment syndrome and can be relieved by incising the fibrous arch.6,7,8,9 It also is a cause of pain restricted to this area, which may present as a resistant “tennis elbow” (see Fig. 4-13).10

The great variations that occur in the site, size, and quality of the

ulnar head of the muscle sometimes cause the nerve to become trapped as

it traverses the muscle, producing the pronator syndrome, which mimics

the carpal tunnel syndrome, but includes pain and paresthesia to the

proximal end of the volar aspect of the forearm.11,12

Understandably, the syndrome occurs when the muscle contracts and

further compresses the nerve. In this syndrome, the intrinsic muscles

of the thumb become weak, but the muscles that are innervated by the

anterior interosseous nerve (the flexor pollicis longus, the flexor

profundus to the index and middle fingers, and the pronator quadratus)

are spared (see Fig. 4-12).

The tendons of the muscle form well above the wrist. Functionally, it

is four separate muscles; it can flex each finger independently, in

contrast to the mass action of the flexor digitorum profundus.

may have to be detached to expose the anterior part of the shaft of the

radius (see Figs. 4-13 and 4-15).

Because the muscle is relaxed totally when the forearm is pronated

fully, some authors suggest that distal radial fractures should be

immobilized in pronation. Clearly, however, the pronator quadratus is

not the only possible deforming force on the distal radius; the best

position for immobilizing reduced fractures of the distal radius still

is a matter of debate.

is the motor nerve of the extensor compartment of the forearm. A branch

of the radial nerve, it passes between the two heads of origin of the

supinator muscle and actually may come in direct contact with the

periosteum of the neck of the radius. At that point, it may be trapped

beneath incorrectly positioned plates or retractors. After emerging

from the supinator muscle,

the

nerve passes down over the origin of the abductor pollicis longus

muscle to reach the interosseous membrane. It continues distally on the

interosseous membrane to the wrist joint, which it supplies with some

sensory branches. The nerve supplies the muscles that arise from the

common extensor origin and the deep muscles of the extensor compartment

of the forearm.

|

|

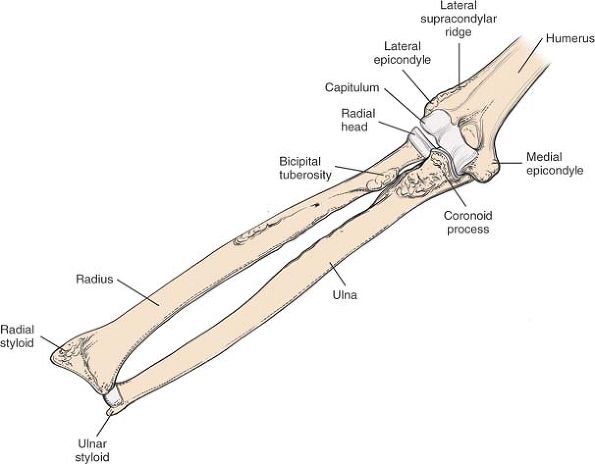

Figure 4-16 The bones of the forearm.

|

all approaches to the upper third of the radial shaft. Although the

nerve can be protected if the insertion of the supinator is detached

and the muscle is stripped off the bone subperiosteally, it can be

argued that the only certain protection as the upper third of the

radius is plated comes from identifying and preserving the nerve via a

posterior approach (see Figs. 4-34 and 4-35).

usually passes between the heads of the pronator teres muscle, whereas

the ulnar artery passes deep to both the heads. Distal to the pronator

teres, the median nerve joins the ulnar artery and passes beneath the

fibrous arch of origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle.

Then, it runs down the flexor aspect of the forearm, roughly in the

midline (see Figs. 4-13 and 4-14).

superficialis muscle, the median nerve sometimes is mistaken for the

superficial tendon to the index finger. To differentiate nerve from

tendon, try to find an artery on the structure in question: the median

nerve has the median artery running along its surface. The artery,

derived from the anterior interosseous artery, is the original fetal

axial artery (see Fig. 4-14).

as a graft for tendon repairs. Because it is absent in 10% of the

population, it must be identified in the conscious patient before

surgery is undertaken. To find it, instruct the patient to touch the

thumb and little fingers together while flexing the wrist against

resistance. Then, palpate the tendon, which stands out prominently in

the forearm (see Fig. 4-11).

palmaris longus at the wrist. In the patient with an absent palmaris

longus, the nerve actually may be mistaken for the tendon (see Fig. 4-11).

four tendons, making it a mass action muscle that is used mainly for power grip.

nerve arises from the median nerve shortly after the median nerve

enters the forearm; the two lie under the tendinous origin of the deep

head of the pronator teres (see Figs. 4-11 and 4-13).

The anterior interosseous nerve may be compressed at this point,

producing the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: paralysis of the

flexor pollicis longus and flexor profundus tendons to the index and

middle fingers, as well as of the pronator quadratus muscle.14,15,16

strong fascia. Fractures bleed, which increases the pressure within

these compartments. As the pressure increases, the venous return

decreases; in certain cases, the pressure becomes so high that it

reduces the arterial blood supply to the muscles and creates muscle

ischemia. Muscle ischemia in turn creates edema, further increasing

compartment pressure. This is known as a compartment syndrome. Muscle

ischemia produces pain disproportionate to the other injuries; if the

pressure within the compartment is not relieved within a short period

of time, permanent muscle necrosis will occur with associated damage to

the nerves traversing the affected compartment (Volkman’s ischemic

contracture). In extreme cases, arterial occlusion occurs, leading to

gangrene.

|

|

Figure 4-17 (A)

To decompress the flexor compartments of the forearm begin by making a longitudinal incision extending for the lateral side of the elbow crease to the radial styloid process. (B) Deepen the skin incision to reveal the fascia covering the flexor muscles; the skin edges will spring apart. (C) Deepen the skin incision to reveal the fascia covering the flexor muscles; the skin edges will spring apart. |

the anterior forearm compartment. It can be decompressed by incising

the deep fascia that covers it along its entire length. In cases of

compartment syndrome, both the superficial and the deep compartments on

the volar side should be released along with the posterior compartment.

The incisions used may also be taken down to the wrist crease and into

the hand for release of the carpal tunnel and the deep palmar space.

Such incisions may also be extended proximally to the anterior lateral

approach to the humerus (Fig. 4-17 and 4-18).

|

|

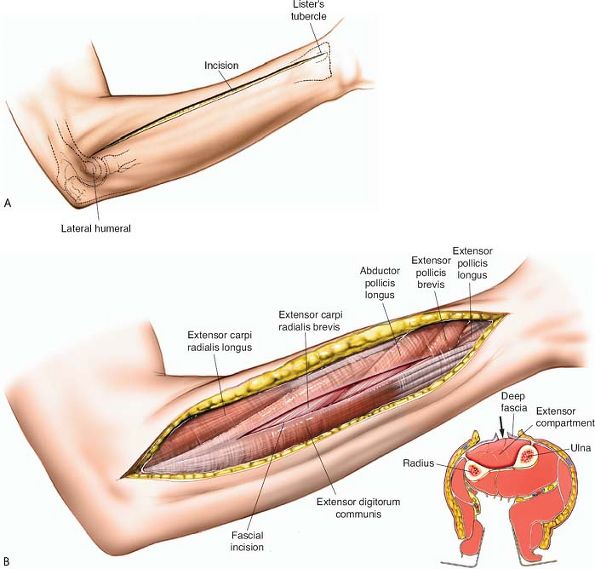

Figure 4-18 (A)

To decompress the posterior compartment, make a longitudinal incision overlying the posterior aspect of the forearm extending from the lateral humeral epicondyle to Lister’s tubercle. (B) Incise the fascia overlying the posterior muscle mass in the line of the skin incision. |

forearm approaches, uncovering the entire length of bone. The exposure

uses the internervous plane between the extensor carpi ulnaris and

flexor carpi ulnaris muscles. Both muscles attach by a shared

aponeurosis into the subcutaneous border of the ulna, the border of

bone that is exposed initially during the approach.

internervous plane share a common aponeurosis, they cannot be separated

at their origin, and the plane is difficult to define. Fibers of the

extensor carpi ulnaris usually have to be detached from the aponeurosis.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of ulnar fractures

-

Treatment of delayed union or nonunion of ulnar fractures

-

Osteotomy of the ulna

-

Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis

-

Treatment of the fibrous anlage of the ulna in cases of ulnar clubhand2

-

Ulnar lengthening (in Kienböck’s disease)17

-

Ulnar shortening (in cases of distal radial malunion)

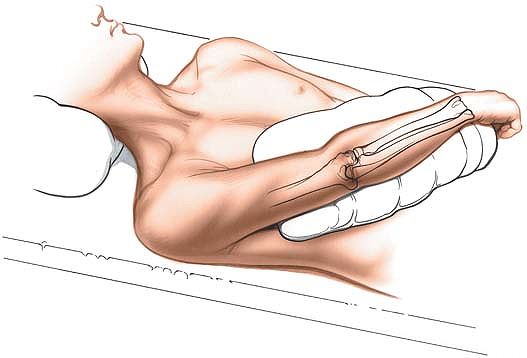

arm placed across the chest to expose the subcutaneous border of the

ulna. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes

or by applying a soft rubber bandage and then a tourniquet (Fig. 4-19).

the operating table, and get the surgical assistant to hold the

patient’s hand so that the forearm is vertical.

|

|

Figure 4-19 Position of the patient on the operating table, for exposure of the shaft of the ulna.

|

|

|

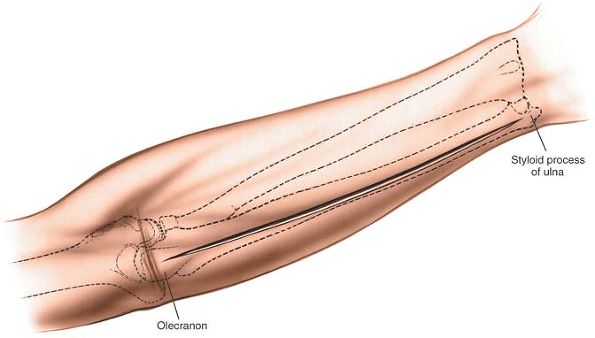

Figure 4-20 Incision for ulnar exposure. Make a longitudinal incision over the subcutaneous border of the ulna.

|

|

|

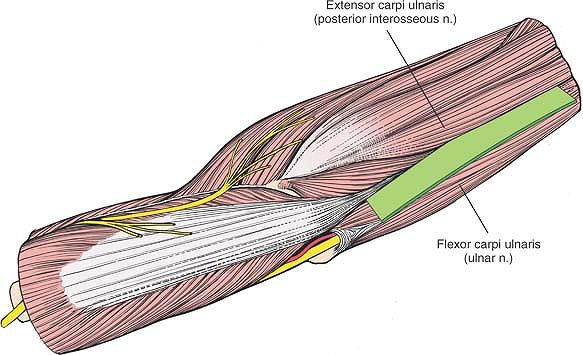

Figure 4-21

The internervous plane lies between the extensor carpi ulnaris (posterior interosseous nerve) and the flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve). |

subcutaneous border of the ulna. The length of the incision depends on

the amount of bone that is to be exposed. In cases of fracture, center

the incision over the fracture site (Fig. 4-20).

|

|

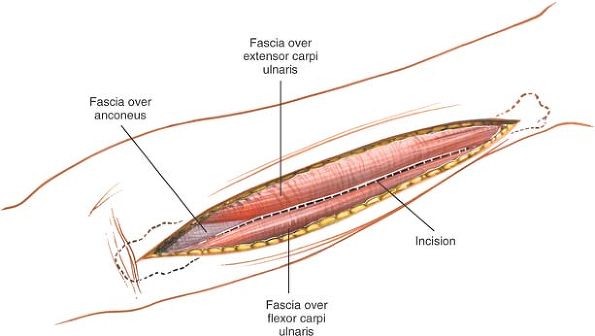

Figure 4-22 Make an incision through the fascia onto the subcutaneous border of the ulna.

|

deep fascia along the same line as the skin incision; continue the

dissection down to the subcutaneous border of the ulna (Fig. 4-22). Even though the bone feels subcutaneous in its middle third,

the fibers of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle nearly always have to be divided to reach the bone.

|

|

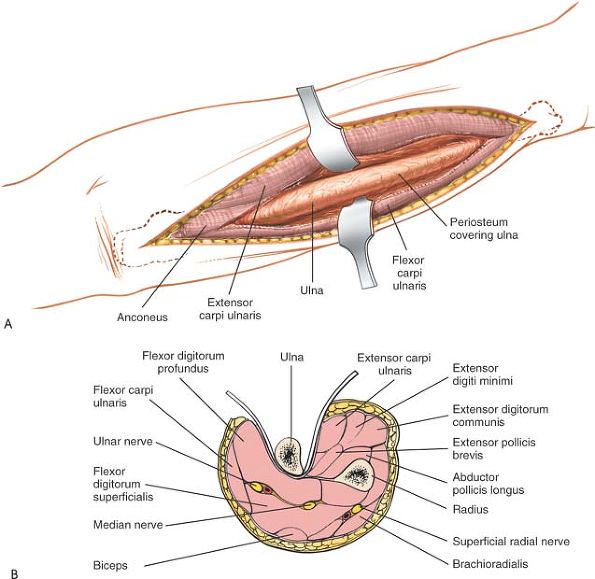

Figure 4-23 (A)

Lift the periosteum longitudinally on the posterior aspect of the ulna, both radially and medially, to expose the entire posterior length of the ulna. (B) Epi-periosteal dissection around the ulna is safe; the muscle masses on each side protect the vital structures. |

and anconeus muscles run along the plane of dissection. The plane still

is an internervous plane, because the anconeus is supplied by the

radial nerve and the flexor carpi ulnaris is supplied by the ulnar

nerve.

providing access to the fracture, continue the dissection in the

epi-periosteal plane to expose either the flexor or extensor aspects of

the bone as needed. Keep soft tissue stripping to a minimum to preserve

blood supply to the fracture (Fig. 4-23).

of the triceps tendon will need to be detached to gain access to the

bone. This insertion is very broad and long, and it blends in with the

periosteum of the subcutaneous surface of the olecranon.

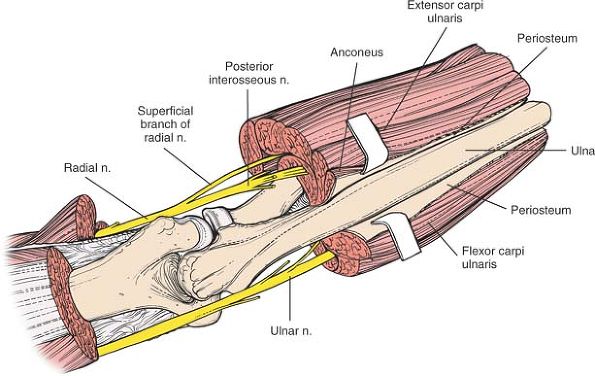

profundus. The nerve is safe as long as the flexor carpi ulnaris is

stripped off the ulna epi-periosteally. If the dissection strays into

the substance of the muscle, however, the nerve may be damaged. Because

the nerve is most vulnerable during very proximal dissections, it

should be identified as it passes through the two heads of the flexor

carpi ulnaris before the muscle is stripped off the proximal fifth of the bone (Fig. 4-24).

down the forearm with the ulnar nerve, lying on its radial side.

Therefore, it also is vulnerable when dissection of the flexor carpi

ulnaris is not carried out subperiosteally (see Fig. 4-23B).

|

|

Figure 4-24

The ulnar nerve is vulnerable during the most proximal dissections of the ulna. It must be identified before muscle is stripped from bone in the proximal fifth. |

can be extended over the olecranon and up the back of the arm, however,

either to expose the elbow joint through an olecranon osteotomy or to

approach the posterior aspect of the distal two thirds of the humerus.

the flexor carpi ulnaris (which is supplied by the ulnar nerve) and the

extensor carpi ulnaris (which is supplied by the posterior interosseous

nerve; see Fig. 4-24).

the flexor carpi ulnaris, effectively tethers the nerve, preventing

further distal mobilization during decompression at the elbow.

Compression lesions of the nerve have been described (see Fig. 3-40).18,19

is the most medial of the muscles that are innervated by the posterior

interosseous nerve. Thus, it forms one border of the internervous plane

between the muscles that are innervated by the posterior interosseous

nerve and those that are innervated by the ulnar nerve, the most medial

of which is the flexor carpi ulnaris (see Fig. 4-21).

the medial side of the forearm between the flexor digitorum profundus

and the flexor digitorum superficialis, and under the flexor carpi

ulnaris. In the forearm, it supplies the flexor carpi ulnaris and the

ulnar half of the flexor digitorum profundus (see Figs. 3-40 and 4-14).

terminal branch of the brachial artery. It usually enters the forearm

deep to the deep head of the pronator teres before angling medially

across the forearm and passing under the fibrous arch of the flexor

digitorum superficialis, where it runs just deep to the median nerve

(see Figs. 4-12, 4-13 and 4-14).

In the distal two thirds of the forearm, the artery runs on the lateral

side of the ulnar nerve, lying on the flexor digitorum profundus and

under the flexor carpi ulnaris. The artery has one major branch in the

forearm, the common interosseous artery, which divides almost

immediately into two tributaries, the anterior interosseous artery

(which runs down the forearm in the midline, lying on the interosseous

membrane) and the posterior interosseous artery (which pierces the

interosseous membrane, running down the forearm in its posterior

compartment; see Fig. 4-14).

during superficial dissection if the dissection strays to the flexor

side of the bone.

The principal aim of the approach is to isolate and retract the

posterior interosseous nerve before exposing the most proximal parts of

the radial shaft, keeping the nerve under direct observation during all

stages of the subsequent procedure and protecting it from damage. The

uses of the posterior approach include the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

radial fractures (the approach provides access to the extensor side of

the bone; this is the tensile side of the bone, where plates should be

placed, if possible) -

Treatment of delayed union or nonunion of fractures of the radius

-

Access to the posterior interosseous

nerve; decompression of the nerve as it passes through the arcade of

Frohse for nerve paralysis or resistant tennis elbow9 -

Radial osteotomy

-

Treatment of chronic osteomyelitis of the radius

-

Biopsy and treatment of bone tumors

-

Place the patient supine on the operating

table, with the arm on an arm board. Pronate the patient’s arm to

expose the extensor compartment of the forearm. -

Place the patient’s arm across the chest. Supinate the forearm to expose its extensor compartment (Fig. 4-25).

If the ulna must be approached as well as the radius, this position

will allow easier access to the ulna through a separate incision.

|

|

Figure 4-25 Position of the patient’s arm on the operating table, for the posterior approach to the radius.

|

the arm for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage or

exsanguinator. Then, apply a tourniquet.

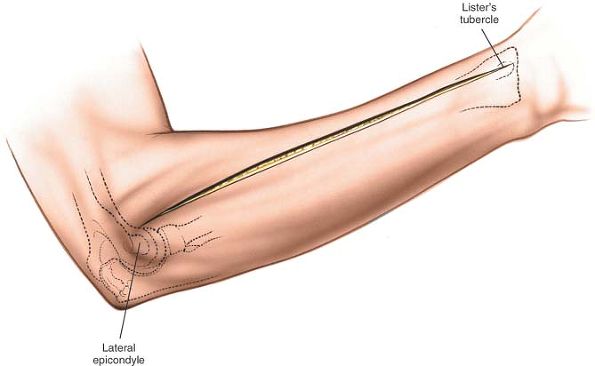

just lateral to the olecranon process on the distal humerus. It is a

prominent bony landmark, but is somewhat smaller and less defined than

the medial epicondyle of the humerus.

dorsoradial tubercle) lies about a third of the way across the dorsum

of the wrist from the styloid process of the radius. It feels like a

small, longitudinal bony prominence or nodule.

anterior to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (along the dorsal

aspect of the forearm) to a point just distal to the ulnar side of

Lister’s tubercle at the wrist (Fig. 4-26).

given operation. In cases of fracture, the incision should be centered

over the fracture site. Use of an image intensifier may allow more

accurate placement of the incision.

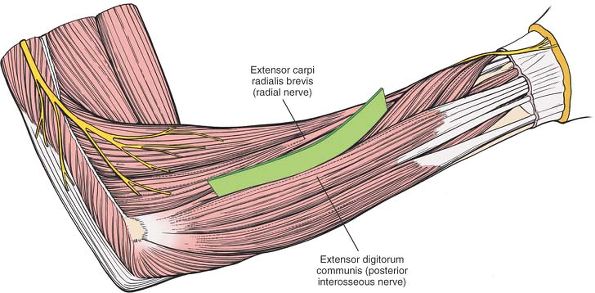

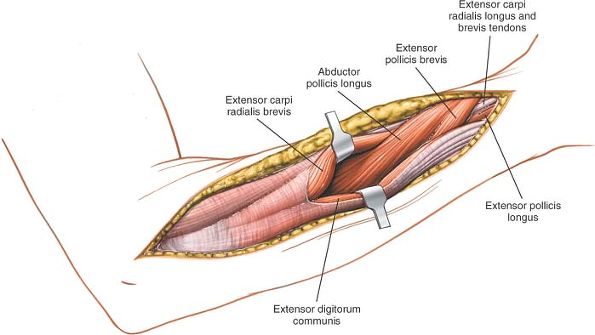

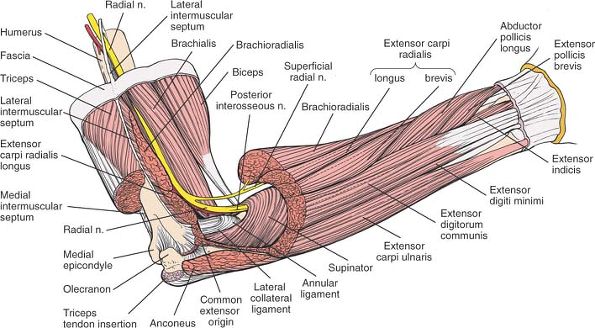

plane lies between the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle (which is

supplied by the radial nerve) and the extensor digitorum communis

muscle (which is supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve; Fig. 4-27). The common aponeurosis of these muscles is the cleavage plane.

plane lies between the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle (which is

supplied by the radial nerve) and the extensor pollicis longus muscle

(which is supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve).

|

|

Figure 4-26

The long incision extends from just anterior to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus to just distal to the ulnar side of Lister’s tubercle at the wrist. |

|

|

Figure 4-27

The internervous plane lies between the extensor carpi radialis brevis (radial nerve) and the extensor digitorum communis (posterior interosseous nerve). |

|

|

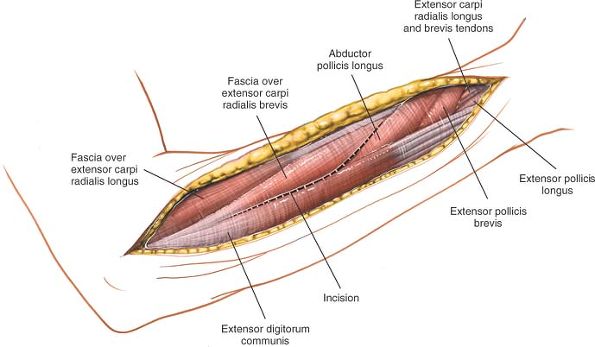

Figure 4-28

Incise the deep fascia and identify the space between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis. The identification is easier distally. |

and identify the space between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and

the extensor digitorum communis. This plane is more obvious distally,

where the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis

emerge from between the two muscles. Proximally, the extensor carpi

radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis share a common

aponeurosis (Figs. 4-28 and 4-29).

|

|

Figure 4-29 The interval between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis.

|

|

|

Figure 4-30 The supinator muscle, beneath the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor pollicis longus.

|

|

|

Figure 4-31

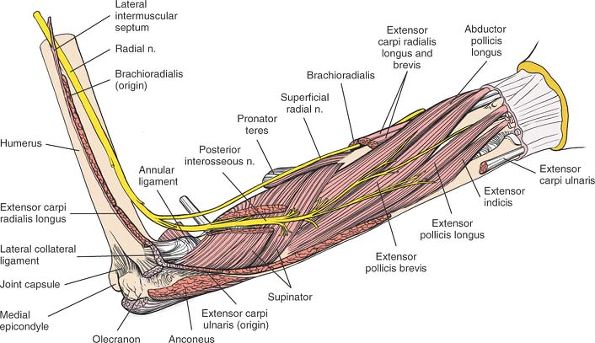

The supinator cloaks the upper third of the radius; the posterior interosseous nerve runs through its substance. The nerve must be protected and identified as it traverses the muscle. The interosseous nerve is seen in the substance of the supinator (inset). |

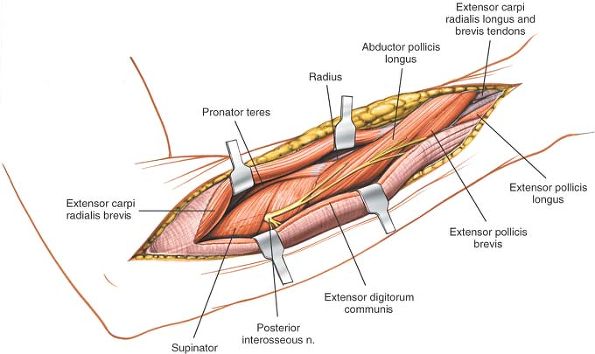

muscles to reveal the upper third of the shaft of the radius, which is

covered by the enveloping supinator muscle.

pollicis brevis, identify the intermuscular plane between the extensor

carpi radialis brevis and the extensor pollicis longus. Separating the

two muscles exposes the lateral aspect of the shaft of the radius (Figs. 4-30 and 4-31).

upper third of the radius; the posterior interosseous nerve runs within

its substance between the superficial and deep heads. The nerve emerges

from between the superficial and deep heads of the supinator muscle

about 1 cm proximal to the distal edge of the muscle. At this point, it

divides into branches that supply the extensors of the wrist, fingers,

and thumb (see Fig. 4-31).

|

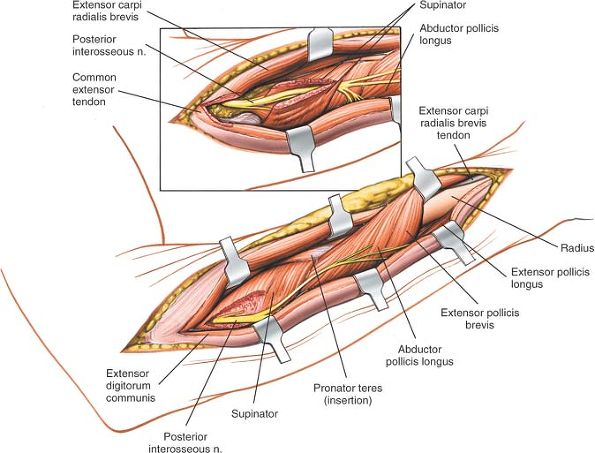

|

Figure 4-32

Detach the insertion of the supinator from the anterior aspect of the radius, with the arm in full supination to bring the origin of the supinator into view and to move the posterior interosseous nerve away from the area of incision. Along the distal third of the bone, the extensor carpi radialis brevis has been separated from the extensor pollicis longus, uncovering the lateral border of the radius. |

-

Proximal to distal (see Fig. 4-31 inset).

Detach the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis and part of the

origin of the extensor carpi radialis longus from the lateral

epicondyle and retract these two muscles laterally. Next, identify the

posterior interosseous nerve proximal to the proximal end of the

supinator muscle by palpating the nerve. Now, carefully dissect the

nerve out through the substance of the supinator, in a proximal to

distal direction, taking great care to preserve the multiple motor

branches to the muscle itself. -

Distal to proximal (see Fig. 4-31).

Identify the nerve as it emerges from the supinator. Note that it

emerges about 1 cm proximal to the distal end of the muscle. Now,

follow the nerve proximally through the substance of the muscle, taking

care to preserve all muscular branches.

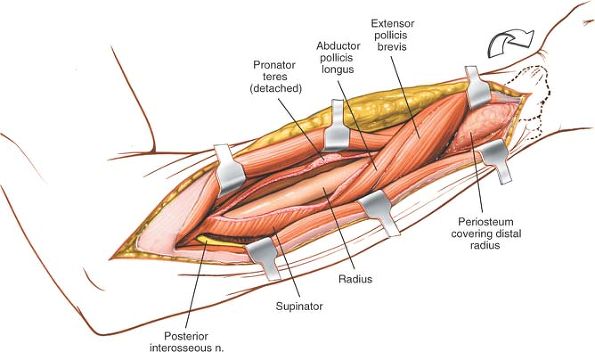

successfully, fully supinate the arm to bring the anterior surface of

the radius into view. Detach the insertion of the supinator muscle from

the anterior aspect of the radius. Strip the supinator off the bone

subperiosteally to expose the proximal third of the shaft of the radius

(Fig. 4-32).

extensor pollicis brevis, blanket this approach as they cross the

dorsal aspect of the radius before heading distally and radially across

the middle third of the radius. To retract them off the bone, make an

incision along their superior and inferior borders. Then, they can be

separated easily from the underlying radius and retracted either

distally or proximally, depending on the exposure that is required (see

Fig. 4-32). Plates can be slid underneath these muscles if required for fixation.

extensor pollicis longus already has led directly onto the lateral

border of the radius (see Fig. 4-32).

-

Identification of the nerve.

In 25% of patients, the posterior interosseous nerve actually touches

the dorsal aspect of the radius opposite the bicipital tuberosity;

plates placed high on the dorsal surface of the radius may trap the

nerve underneath.21 Identifying and

preserving the nerve in the supinator muscle is the only means of

ensuring that it will not be trapped beneath any plate that is applied

for a radial fracture (see Fig. 4-31). -

Protecting the nerve with the supinator muscle.

Strip the supinator off the anterior aspect of the radius and retract

it radially, with the nerve still enclosed in its substance. This

technique often is used in the anterior approach to the radius,

exposing the anterior surface of the bone. The dorsal aspect of the

radius can be exposed in the same way, but because the posterior

interosseous nerve actually touches the periosteum in one of four

patients, the safest procedure is to dissect the nerve out fully before

stripping the muscle from the bone (see Fig. 4-32).

brevis and extensor digitorum communis muscles, detach the origin of

the extensor carpi radialis brevis from the common extensor origin on

the lateral epicondyle of the humerus.

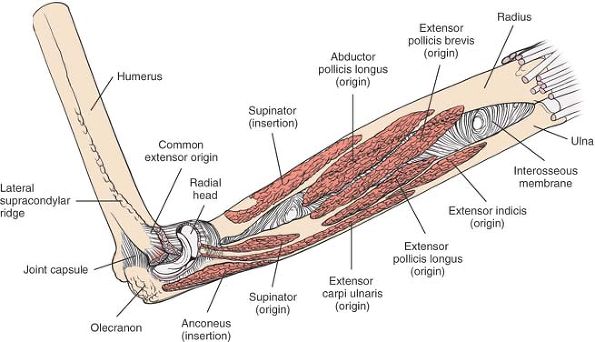

-

The mobile wad of three

(the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor

carpi radialis brevis) runs along the lateral side of the forearm.

These three muscles arise from a continuous line on the lateral

supracondylar ridge and lateral epicondyle of the humerus. -

The four superficial extensor muscles

fan out from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. From the ulnar to

the radial side of the forearm, they consist of the anconeus, the

extensor carpi ulnaris, the extensor digiti minimi, and the extensor

digitorum communis (Figs. 4-33 and 4-34).

Two internervous planes exist in this layer of musculature: between the

extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is supplied by the posterior

interosseous nerve) and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is

supplied by the ulnar nerve) on the ulnar side (see Fig. 4-21), and between the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle22

(which is supplied by the radial nerve) and the extensor digitorum

communis muscle (which is supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve)

on the radial side (see Fig. 4-27). -

Of the five deep muscles,

three (the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis brevis, and

the extensor pollicis longus) supply the thumb. The three

P.177P.178

cross

the forearm obliquely from the ulnar to the radial side, and two of

them (the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis)

wind around the dorsal and lateral aspects of the radius. The remaining

two muscles of the deep group are the supinator and the extensor

indicis (Fig. 4-35).

|

|

Figure 4-33 Superficial muscles of the posterior aspect of the forearm.

|

|

|

Figure 4-34

The superficial muscles have been removed to reveal the course of the posterior interosseous nerve as it enters the supinator muscle through the arcade of Frohse and the course of the superficial radial nerve, which is sensory and supplies no muscles of the forearm. |

interosseous nerve, innervates the muscles of the extensor compartment;

it is the key anatomic structure from an operative point of view. The

only major arterial supply of the compartment is the posterior

interosseous artery.

|

|

Figure 4-35 The course of the posterior interosseous nerve through the supinator muscle, as it runs to supply muscles in the forearm.

Extensor Carpi Ulnaris. Origin.

Common extensor origin on lateral epicondyle of humerus and subcutaneous border of ulna. (Shared origin with flexor carpi ulnaris.) Insertion. Base of fifth metacarpal. Action. Extensor and ulnar deviator of wrist. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve. Extensor Digitorum Communis. Origin. Common extensor origin on lateral epicondyle of humerus. Insertion. Into extensor apparatus of fingers. Action. Extensor of wrist and fingers. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

|

lateral to the olecranon process, is smaller than the medial

epicondyle, but its lateral supracondylar line, which runs superiorly,

is longer than the medial supracondylar line, extending almost to the

deltoid tuberosity. The lateral epicondyle is the site of the common

origin of the superficial muscles of the extensor compartment of the

forearm. The extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum

communis,

extensor

digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris all originate from fused

tendons that attach just anterior to the epicondyle. The

brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus arise from the

lateral supracondylar ridge.

lateral epicondylitis; the pain that is characteristic of this

condition can be reproduced by providing resistance to extension of the

wrist.

arcade of Frohse may produce a syndrome similar to lateral

epicondylitis. In these cases, the tenderness usually is elicited more

distally in the course of the posterior interosseous nerve or

anteriorly over the arcade of Frohse. Both conditions can exist in a

single patient.23

forearm crosses the lines of cleavage of the skin at right angles and

often leaves a broad scar.

plane between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor

communis. In the distal third of the wound, the internervous plane lies

between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor pollicis

longus (see Fig. 4-33).

consists of detaching the insertion of the supinator muscle from the

radius while preserving the posterior interosseous nerve (see Fig. 4-32).

mobilizing and retracting two muscles, the abductor pollicis longus and

the extensor pollicis brevis (see Fig. 4-32).

internervous plane between the extensor pollicis longus and the

extensor carpi radialis brevis.

supinator muscle, through which the posterior interosseous nerve passes

on its way to the posterior compartment of the forearm (see Figs. 4-34 and 4-35). For additional information on the supinator muscle, see the section regarding the anterior approach to the radius.

is the motor nerve of the posterior compartment of the forearm. A

branch of the radial nerve, it passes between the two heads of the

supinator muscle and actually may come in direct contact with the neck

of the radius. At that point, it may be trapped beneath incorrectly

positioned plates. After emerging from the supinator muscle, the nerve

passes distally over the origin of the abductor pollicis longus muscle

to reach the interosseous membrane. It continues distally on the

interosseous membrane to the level of the wrist joint, which it

supplies with some sensory branches. The nerve supplies those muscles

that arise from the common extensor origin and the deep muscles of the

extensor compartment of the forearm (see Fig. 4-35).

important to remember that the posterior interosseous nerve is

vulnerable during all approaches to the proximal third of the radial

shaft. Although the nerve can be protected by detaching the insertion

of the supinator and stripping the muscle off the bone subperiosteally,

the only certain protection of the posterior interosseous nerve during

plating of the upper third of the radius may come with full dissection

via a posterior approach.

accompanies the posterior interosseous nerve as it runs along the

interosseous membrane in the proximal two thirds of the forearm. The

posterior interosseous artery enters the extensor compartment of the

forearm by passing between the radius and the ulna through the

interosseous membrane (Fig. 4-36). The artery then joins the posterior interosseous nerve distal to the distal edge of the deep head of the supinator muscle.

dissected easily down to the level of the wrist. Most of the blood

supply for the posterior area comes from an anterior interosseous

artery via branches that perforate the interosseous membrane. The

tendons running in this area may have a marginal blood supply.

approach to the radius, good collateral circulation appears to protect

the extremity from any functional deficits.

|

|

Figure 4-36 The origins and insertions of the muscles of the posterior aspect of the forearm.

Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus. Origin. Lower third of lateral supracondylar ridge of humerus, lateral intermuscular septum of arm. Insertion. Base of second metacarpal. Action. Extensor and radial deviator of wrist. Nerve supply. Radial nerve.

Extensor Carpi Radialis Brevis. Origin. Common extensor origin on lateral epicondyle of humerus and radial collateral ligament of elbow. Insertion. Base of third metacarpal. Action. Extensor and radial deviator of wrist. Nerve supply. Radial nerve.

Supinator. Origin.

From two heads. Superficial head: from lateral epicondyle of humerus, lateral collateral ligament of elbow, and supinator crest of ulna. Deep head: from supinator crest and fossa of ulna. Insertion. Anterior aspect of radius. Action. Supinator of forearm. Weak flexor of elbow. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve. Extensor Pollicis Longus. Origin. Posterior surface of ulna in its middle third and from interosseous membrane. Insertion. Distal phalanx of thumb. Action. Extensor of thumb and wrist. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

Abductor Pollicis Longus. Origin. Posterior surface of ulna, posterior interosseous membrane, and middle third of posterior surface of radius. Insertion. Base of thumb metacarpal. Action. Abductor and extensor of thumb. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

Extensor Pollicis Brevis. Origin. Posterior surface of radius and interosseous membrane. Insertion. Base of proximal phalanx of thumb. Action. Extensor of proximal phalanx of thumb. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

Extensor Indicis. Origin. Posterior surface of ulnar shaft and interosseous membrane. Insertion. Extensor apparatus of index finger via ulnar side of tendon of extensor digitorum that runs to index finger. Action. Extensor of index finger. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

Extensor Digiti Minimi. Origin. Common extensor origin on lateral epicondyle of humerus. Insertion. Extensor apparatus of little finger. Action. Extensor of little finger. Nerve supply. Posterior interosseous nerve.

|

|

|

Figure 4-37 The bones of the posterior aspect of the forearm.

|

F, Frankel M: Die muskeln des menschlichen armes. In: Bardelehen’s

handbuch der anatomie des menschlichen. Jena, Germany, Fisher, 1980

M: The arcade of Prohse and its relationship to posterior interosseous

nerve paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 50:809, 1968

O: Pronator syndrome: compression neuropathy of the median nerve at

level of pronator teres muscle. Georgetown Med Bull 13:232, 1960

M: The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, with special attention to

its variations. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 54A:84, 1970

RB, Linscheid RL, Dobyns JH et al: Ulnar lengthening in the treatment

of Kienböck’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 64:170, 1982

O: Management of peripheral nerve problems. In: Management of nerve

compression lesions of the upper extremity. Philadelphia, WB Saunders,

1980:569