The Elbow

collateral ligaments. The key neurovascular structures running down the

arm pass anterior and posterior to the joint. The medial and lateral

approaches, therefore, avoid the obvious neurovascular dangers, but

provide limited access to the elbow because of its bony configuration.

Anterior and posterior approaches provide better access to the joint,

but may endanger the key neurovascular structures.

provides the best possible exposure to all surfaces of the elbow and is

the approach used most often for the internal fixation of complex

fractures of this joint. The medial approach

provides good access to the medial side of the joint, but requires an

osteotomy of the medial epicondyle for best exposure. This osteotomy

does not involve any part of the articular surface, however. Although

the approach is extensile to the distal humerus, it is most useful in

dealing with local pathologies of the medial side of the joint. The

anterolateral approach exposes the lateral side of the joint; in

addition, it can be extended both proximally and distally to expose

both the humerus and the radius from the shoulder to the wrist. The anterior approach

to the cubital fossa is designed primarily for exploration of the

critical neurovascular structures that pass in front of the elbow

joint. The posterolateral approach to the radial head is designed exclusively for surgery on that structure.

single section of this chapter after the various surgical approaches

are described, mainly because the keys to the surgical anatomy are the

neurovascular bundles that pass across the elbow joint; their positions

are important in all the approaches. Separate subsections outline the

anatomy that applies to each particular approach.

Although it is basically a safe and reliable operative technique, it

does have one major drawback: it usually requires an osteotomy of the

olecranon on its articular surface, creating another “fracture” that

must be internally fixed. The uses of the posterior approach include

the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the distal humerus3,4

-

Removal of loose bodies within the elbow joint

-

Treatment of nonunions of the distal humerus

using some portions of this approach to lengthen the triceps muscle,

without performing an olecranon osteotomy.

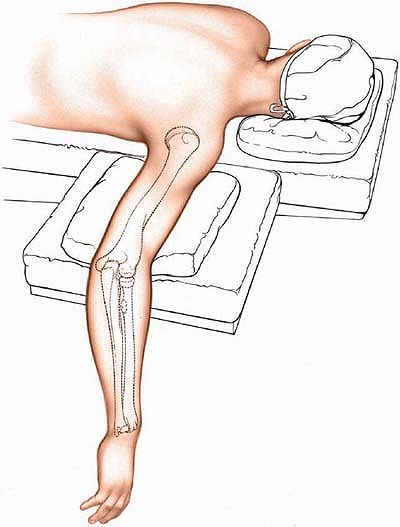

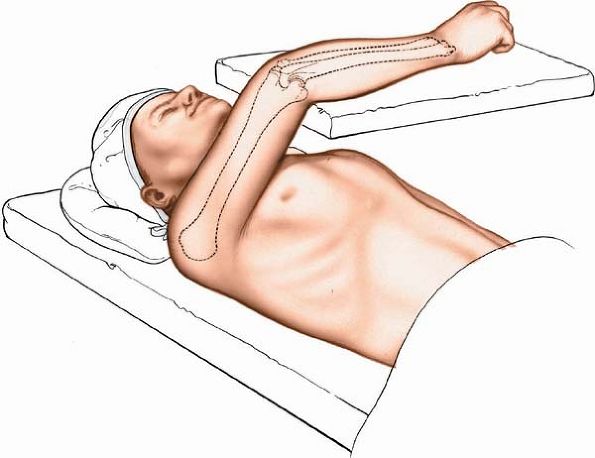

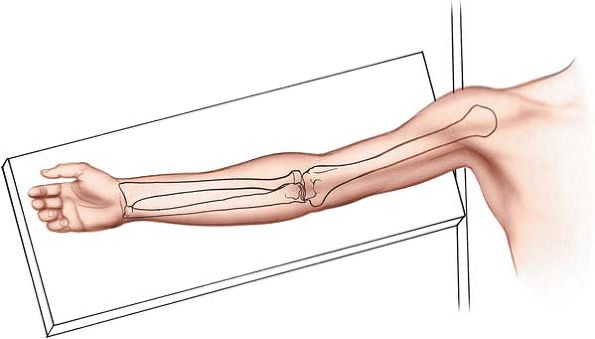

table, ensuring adequate padding for the chest and pelvis to allow free

movement of the abdomen during respiration. Exsanguinate the limb by

elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes and then apply a tourniquet as high up

on the arm as possible. Abduct the arm about 90° and place a small

sandbag underneath the tourniquet, elevating the upper arm from the

operating table. Allow

the elbow to flex and the forearm to hang over the side of the table (Fig. 3-1).

|

|

Figure 3-1 Position of the patient on the operating table.

|

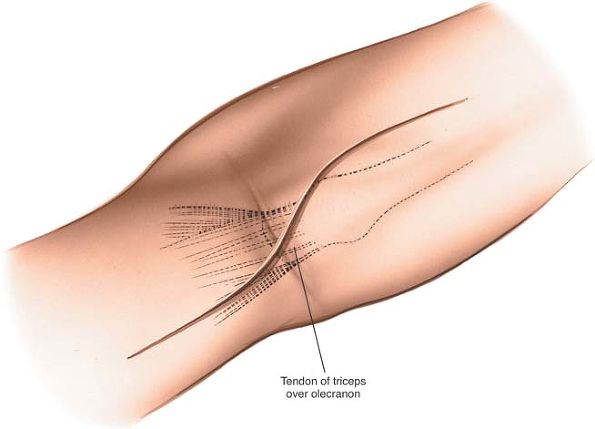

the elbow. Begin 5 cm above the olecranon in the midline of the

posterior aspect of the arm. Just above the tip of the olecranon, curve

the incision laterally so that it runs down the lateral side of the

process. To complete the incision, curve it medially again so that it

overlies the middle of the subcutaneous surface of the ulna. Running

the incision around the tip of the olecranon moves the suture line away

from devices that are used to fix the olecranon osteotomy and away from

the weight-bearing tip of the elbow (Fig. 3-2).

|

|

Figure 3-2 Incision for the posterior approach to the elbow.

|

approach involves little more than detaching the extensor mechanism of

the elbow. The nerve supply of the triceps muscle (the radial nerve)

enters the muscle well proximal to the dissection.

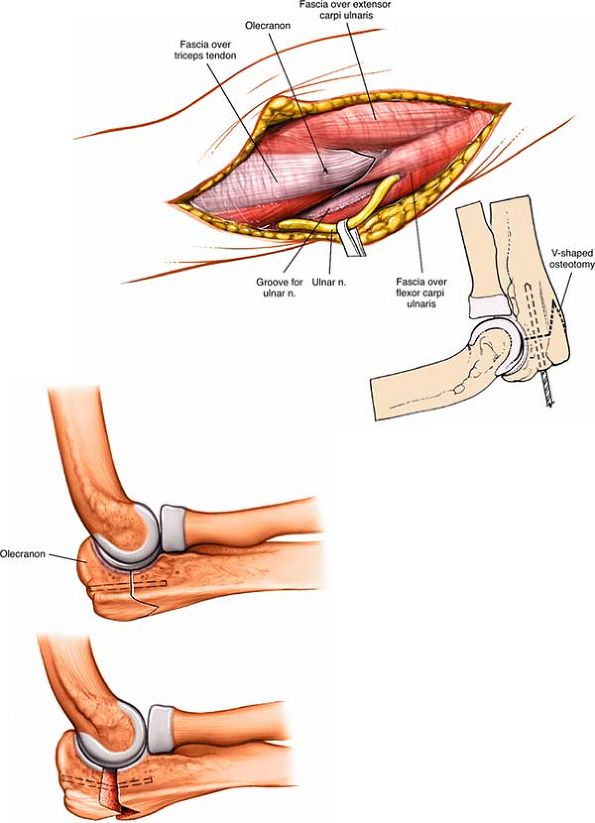

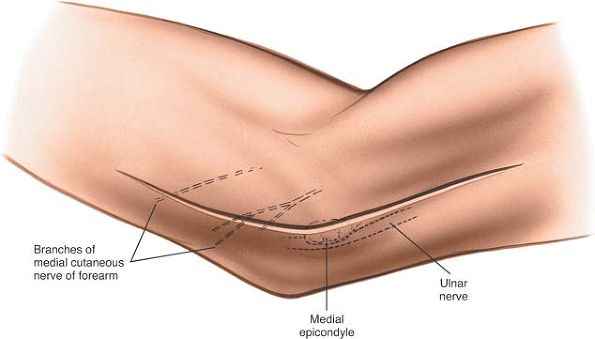

nerve as it lies in the bony groove on the back of the medial

epicondyle and incise the fascia overlying the nerve to expose it.

Fully dissect out the ulnar nerve and pass tapes around it so that it

can be identified at all times (Fig. 3-3). Do not use these tapes for retraction as this can create a traction lesion to the nerve.

the osteotomy is performed. Score the bone longitudinally with an

osteotome so that the pieces can be aligned correctly when the

osteotomy is repaired (see Fig. 3-3, inset).

|

|

Figure 3-3

Dissect the ulnar nerve from its bed and hold it free with tape. Predrill the olecranon before performing an osteotomy for easy reattachment. A V-shaped osteotomy is inherently more stable than a transverse osteotomy. |

from its tip using an oscillating saw. The apex of the V is directed

distally. A V-shaped osteotomy gives greater stability than a

transverse osteotomy after fixation. Divide the bone until it is cut

through almost entirely. Snap the remaining cortex by wedging the two

cut surfaces apart with an osteotome. This will cause an irregularity

in the osteotomy, allowing it to key together better during

reconstruction (see Fig. 3-3, inset).

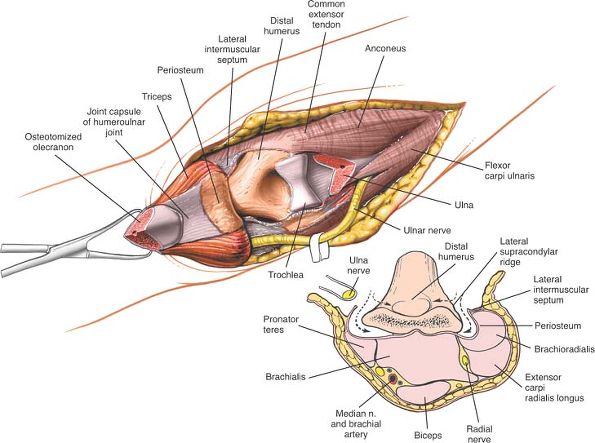

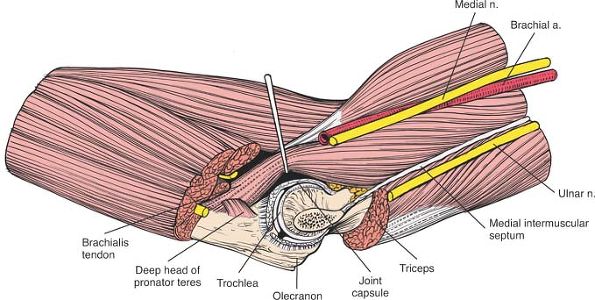

lateral sides of the portion of the olecranon that has been subjected

to osteotomy and retract it proximally, elevating the triceps from the

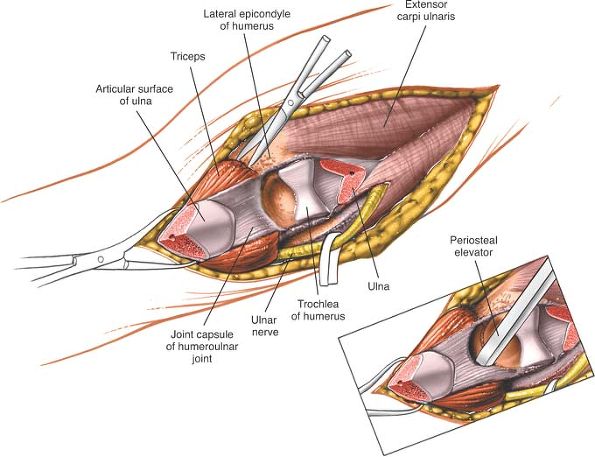

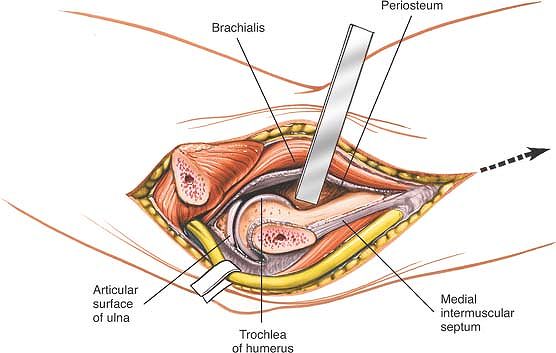

back of the humerus (Fig. 3-4). The posterior

aspect of the distal end of the humerus is directly underneath;

subperiosteal dissection around the medial and lateral borders of the

bone allows exposure of all surfaces of the distal fourth of the

humerus (Fig. 3-5). Note that full exposure

seldom will be needed. All the soft-tissue attachments to bone that can

be preserved should be, particularly in reductions of fractures.

Stripping excessive soft-tissue attachments off the bone leaves the

bone fragments without a vascular supply and jeopardizes healing.

|

|

Figure 3-4

Perform a V-shaped osteotomy of the olecranon and retract it proximally, with the triceps muscle attached. Strip a portion of the joint capsule with an osteotome. |

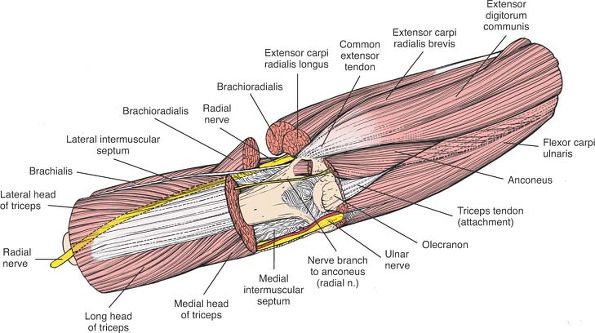

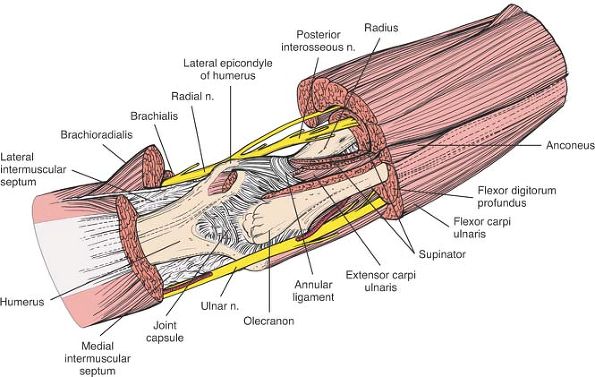

the distal fourth of the humerus, because the radial nerve, which

passes from the posterior to the anterior compartment of the arm

through the lateral intermuscular septum, may be damaged. Flex the

elbow to relax the anterior structures if they need to be elevated off

the front of the humerus (see Figs. 2-36 and 2-37).

field during all stages of the dissection. Some surgeons advise routine

anterior transposition of the nerve during closure, especially if

implant removal is anticipated in the future.

|

|

Figure 3-5 Dissect around the medial and lateral borders of the bone to expose all the surfaces of the distal fourth of the humerus.

|

anterior to the distal humerus. It may be endangered if the anterior

structures are not stripped off the distal humerus. In cases of

fracture, this dissection has usually been done for you. In the

treatment of nonunions or when the approach is used for osteotomies, a

strictly subperiosteal plane must be used to avoid damage to the nerve

(see Fig. 3-5, inset).

if the dissection ventures farther proximally than the distal third of

the humerus, one handbreadth above the lateral epicondyle (see Fig. 2-36).

correctly during closure. Alignment after fractures is easy, because

the uneven ends of the bone usually fit snugly, like a jigsaw puzzle.

Osteotomies may result in flat surfaces, however, and can make accurate

reattachment difficult (see Fig. 3-3).

posterior approach cannot be extended more proximally than the distal

third of the humerus because of the danger to the radial nerve (see Fig. 2-36).

It also can be enlarged to expose the anterior surface of the distal

fourth of the humerus. The ulnar nerve (which runs across the operative

field), median nerve, and brachial artery may be at risk in this

exposure. The uses of the medial approach include the following:

-

Removal of loose bodies (now more commonly removed arthroscopically)

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the coronoid process of the ulna (rarely indicated)

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the medial humeral condyle and epicondyle

side of the joint and should not be used for routine exploration of the

elbow. The joint may be dislocated during the procedure, however, to

gain access to the lateral side of the elbow, if necessary.

|

|

Figure 3-6 Position of the patient on the operating table.

|

the arm supported on an arm board or table. Abduct the arm and rotate

the shoulder fully externally so that the medial epicondyle of the

humerus faces anteriorly. Flex the elbow 90° (Fig. 3-6).

Alternatively, flex the patient’s shoulder and elbow such that the

forearm comes to lie over the front of the face. This allows easier

exposure of the medial side of the elbow, but requires an assistant to

hold the forearm to provide adequate exposure.

minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage (or exsanguinator). Then,

inflate a tourniquet.

|

|

Figure 3-7 Incision for the medial approach to the elbow, centered on the medial epicondyle.

|

|

|

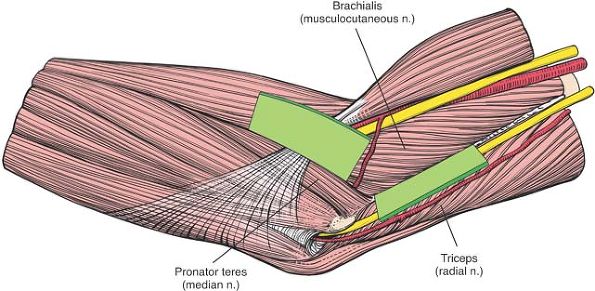

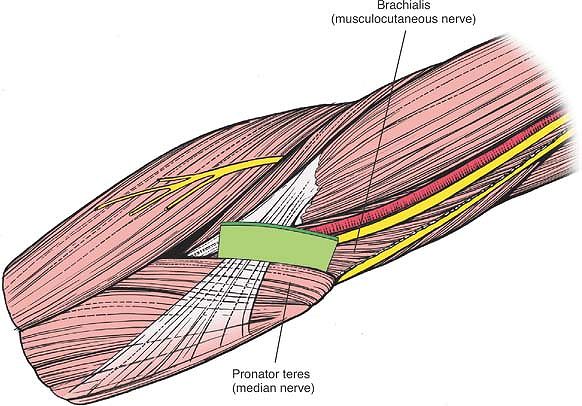

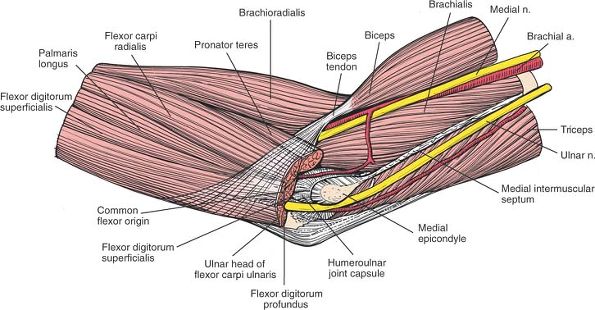

Figure 3-8

Internervous plane. Proximally, the plane is between the brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve) and the triceps (radial nerve); distally, it is between the brachialis and the pronator teres (median nerve). |

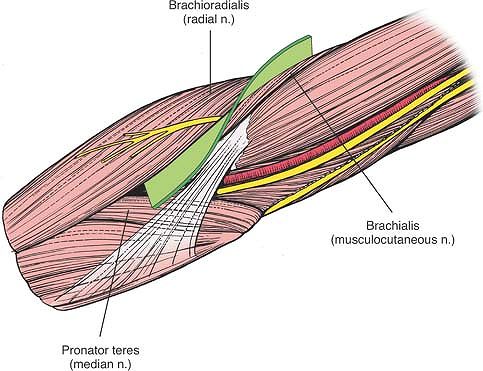

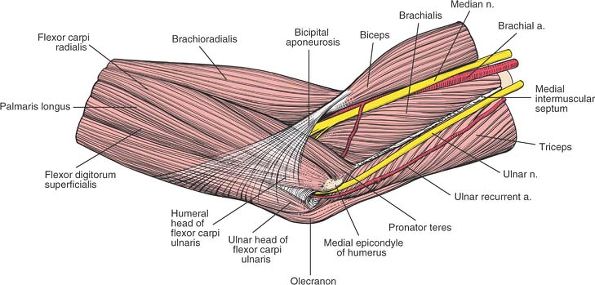

plane lies between the brachialis muscle (which is supplied by the

musculocutaneous nerve) and the triceps muscle (which is supplied by

the radial nerve) (Fig. 3-8).

between the brachialis muscle (which is supplied by the

musculocutaneous nerve) and the pronator teres muscle (which is

supplied by the median nerve; see Fig. 3-8).

|

|

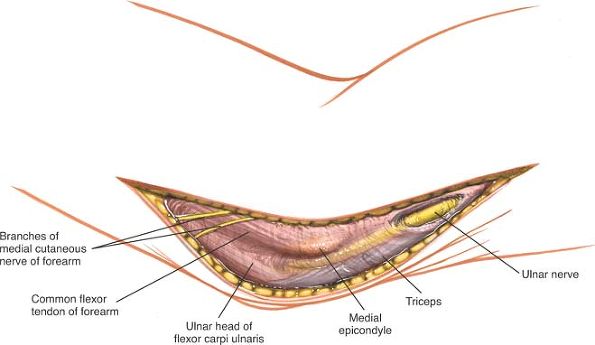

Figure 3-9 Superficial surgical dissection. Isolate the ulnar nerve along the length of the incision.

|

the medial condyle of the humerus. Incise the fascia over the nerve,

starting proximal to the medial epicondyle; then, isolate the nerve

along the length of the incision (Fig. 3-9).

overlying the pronator teres. The superficial flexor muscles of the

forearm now are visible as they pass directly from their common origin

on the medial epicondyle of the humerus (Fig. 3-10).

|

|

Figure 3-10

Retract the skin anteriorly with the fascia to uncover the common origin of the superficial flexor muscles from the medial epicondyle. |

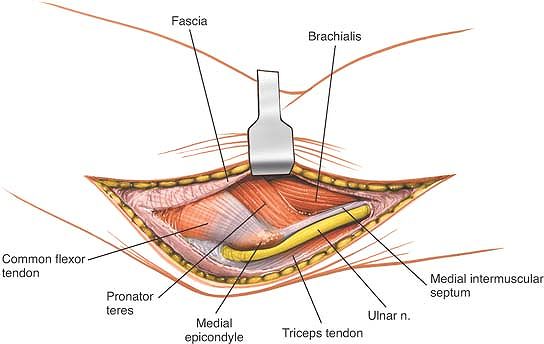

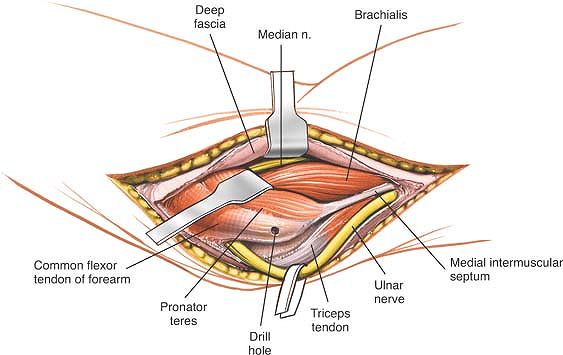

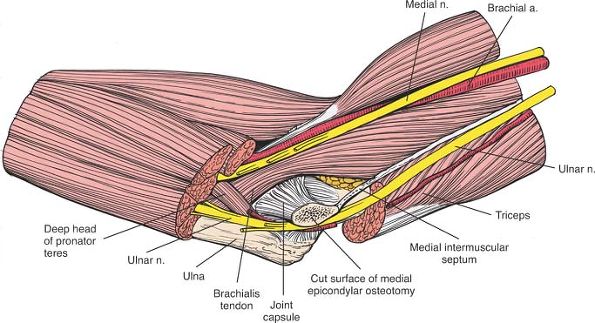

brachialis muscles, taking care not to damage the median nerve, which

enters the pronator teres near the midline. Gently retract the pronator

teres medially, lifting it off the brachialis (Fig. 3-11). Make sure that

the ulnar nerve is retracted inferiorly; then, perform osteotomy of the

medial epicondyle. Place a periosteal elevator beneath the medial

collateral ligament in order to be certain that when the medial

epicondyle is osteotomized the ligament remains attached to the medial

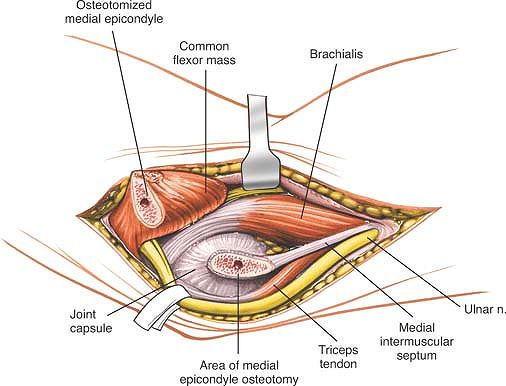

epicondyle. Reflect the epicondyle with its attached flexors distally,

avoiding traction that might damage the median or anterior interosseous

nerves. Superiorly, continue the dissection between the brachialis,

retracting it anteriorly, and the triceps, retracting it posteriorly (Fig. 3-12).

The medial collateral ligaments must be preserved during osteotomy of

the medial epicondyle. Division of this ligament will result in valgus

instability of the elbow.

|

|

Figure 3-11 Enter the interval between the pronator teres and the brachialis. Retract the pronator teres medially.

|

|

|

Figure 3-12

Subject the medial epicondyle to osteotomy and retract it (gently) with its attached flexors. Vigorous retraction of the epicondyle and its attached muscles may stretch the branch of the median nerve to the flexors. |

a traction lesion, with special damage to its multiple branches to the

pronator teres muscle, if the medial epicondyle and its superficial

flexor muscles are retracted too vigorously in a distal direction. Its

major branch, the anterior interosseous nerve, also may suffer a

traction lesion (see Fig. 3-12).

|

|

Figure 3-13 Incise the joint capsule and the medial collateral ligament to expose the joint.

|

can be abducted to open its medial side. To dislocate the elbow, the

joint capsule and periosteum should be stripped off the distal humerus,

working from within the joint. By this means, the mobility of the

proximal ulna will be increased significantly. This increased mobility

then will allow dislocation of the joint laterally, thereby opening all

the surfaces of the joint to inspection.

Enlarge the exposure proximally by developing the plane between the

triceps and brachialis muscles. Subperiosteal dissection and elevation

of the brachialis expose the anterior surface of the distal fourth of

the humerus (see Figs. 3-13 and 3-39).

medial epicondyle of the humerus, with its attached flexor muscles, can

be retracted only as far as the branches from the median nerve allow.

Thus, although the exposure provides an adequate view of the brachialis

inserting into the coronoid, it cannot offer a more distal exposure of

the ulna.

the elbow joint, especially the capitulum and the proximal third of the

anterior aspect of the radius. Its uses include the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the capitulum

-

Excision of tumors of the proximal radius

-

Treatment of aseptic necrosis of the capitulum

-

Drainage of infection from the elbow joint

-

Treatment of neural compression lesions

of the proximal half of the posterior interosseous nerve and of the

proximal part of the superficial radial nerve—access to the arcade of

Frohse, as well as treatment of radial head fractures with paralysis of

this nerve -

Treatment of biceps avulsion from the radial tuberosity

-

Total elbow replacements

approach to the humerus and a proximal extension of the anterior

approach to the radius. Theoretically, the approach can link the two

together to expose the entire upper extremity from shoulder to wrist.

the arm on an arm board. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it

for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage or

exsanguinator. Then, inflate a tourniquet (Fig. 3-14).

|

|

Figure 3-14 Position of the patient on the operating table.

|

palpable as part of a thick wad of muscle on the anterolateral aspect

of the forearm. This “mobile wad” consists of three muscles; the

brachioradialis forms the medial border of the wad.

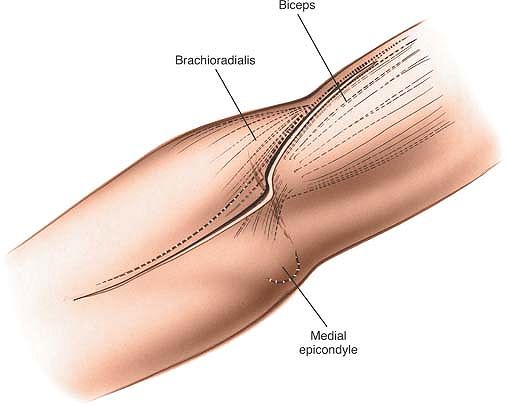

elbow joint. Begin 5 cm above the flexion crease of the elbow, over the

lateral border of the biceps muscle. Follow the lateral border of the

biceps distally, but curve the incision laterally at the level of the

elbow joint to avoid crossing a flexion crease at 90°. Then, continue

the incision inferiorly, curving medially and following the medial

border of the brachioradialis muscle. The lower limit of the extension

depends on the amount of the radius that must be exposed (Fig. 3-15).

|

|

Figure 3-15

Incision for the anterolateral approach to the elbow. The upper portion of the incision follows the lateral border of the biceps muscle. The lower portion follows the medial border of the brachioradialis muscle. |

(which is supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve) and the

brachioradialis muscle (which is supplied by the radial nerve).

muscle (which is supplied by the radial nerve) and the pronator teres

muscle (which is supplied by the median nerve) (Fig. 3-16).

|

|

Figure 3-16

Internervous plane. Proximally, the plane is between the brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve) and the brachioradialis (radial nerve); distally, it is between the brachioradialis and the pronator teres (median nerve). |

sensory branch of the musculocutaneous nerve) as it becomes superficial

to the deep fascia in

the

distal 2 in of the arm lateral to the biceps tendon in the interval

between it and the brachialis muscle. Retract it with the medial skin

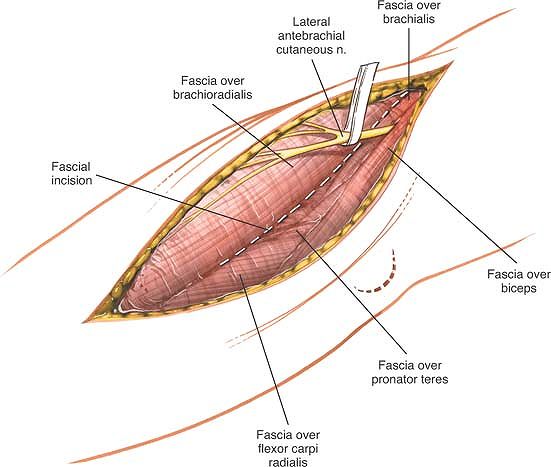

flap (Fig. 3-17).

It is more superficial than the superficial radial nerve, lying outside

the fascial compartment of the brachioradialis; the superficial radial

nerve still lies within the compartment at this level.

|

|

Figure 3-17

Superficial surgical dissection. Incise the deep fascia along the medial border of the brachioradialis. Be careful to identify the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve and retract it. |

|

|

Figure 3-18

Identify the interval between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles. Retract the brachioradialis laterally and the brachialis medially, and identify the radial nerve. |

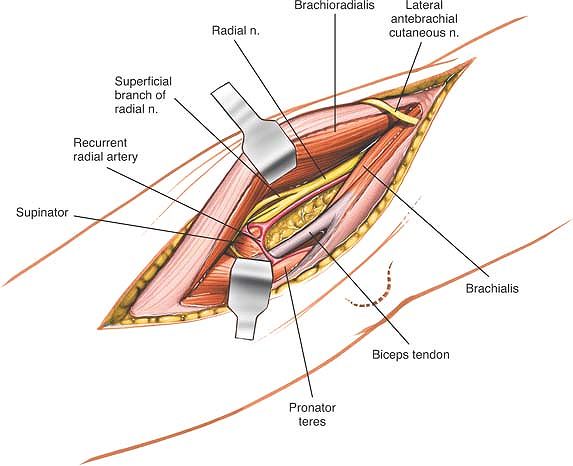

Identify the radial nerve proximally at the level of the elbow joint

between the brachialis and the brachioradialis. It lies deep between

the two muscles and cannot be seen fully until they are separated. The

intermuscular plane is oblique, with the brachioradialis overlying the

brachialis muscle. Develop the plane between the two muscles using your

finger, retracting the brachioradialis laterally and the brachialis and

the overlying biceps brachii medially (Fig. 3-18).

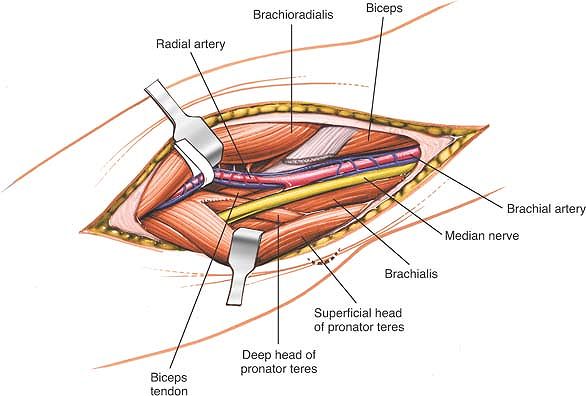

interval until it divides into its three terminal branches: the

posterior interosseous nerve enters the supinator muscle, the sensory

branch passes down the forearm behind the brachioradialis, and the

motor branch to the extensor carpi radialis brevis enters that muscle

almost immediately. Below the division of the nerve, develop a plane

between the brachioradialis on the lateral side and the pronator teres

on the medial side. Ligate the recurrent branches of the radial artery

and the muscular branches that enter the brachialis just below the

elbow so that the muscle can be retracted adequately. Ligation also

allows the radial artery, which runs down the proximal third of the

forearm on the pronator teres, to be retracted medially (Fig. 3-19).

|

|

Figure 3-19

The radial nerve divides into its three terminal branches: the posterior interosseous nerve, the sensory branch (which appears under the brachioradialis), and a motor branch to the extensor carpi radialis brevis. Develop a plane between the brachioradialis and the pronator teres. |

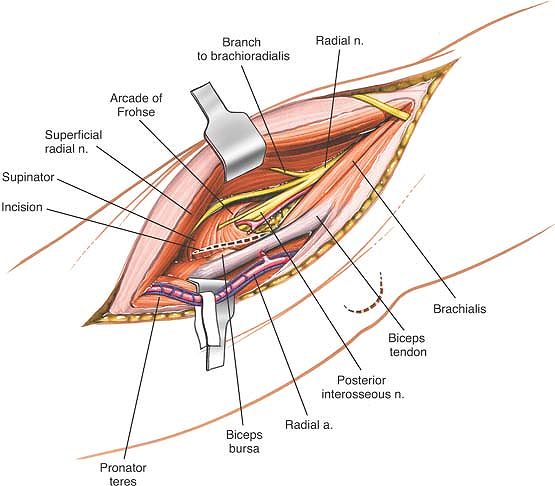

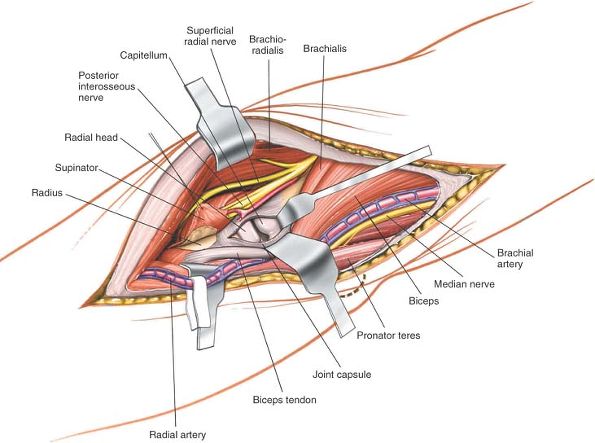

the elbow, make a longitudinal incision in the anterior capsule of the

joint between the radial nerve laterally and the brachialis medially (Fig. 3-20).

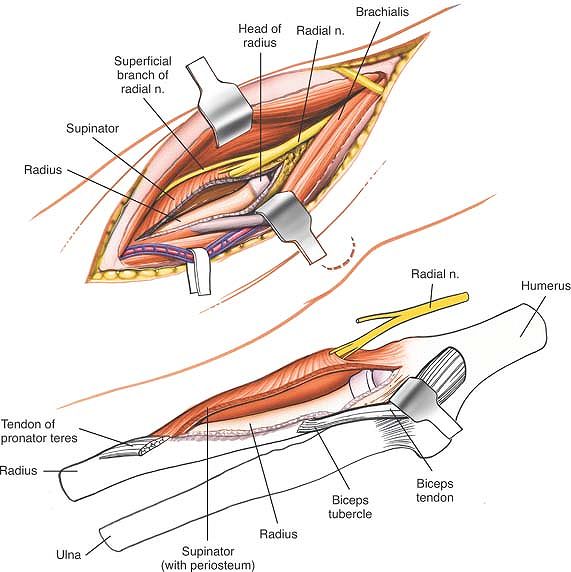

moves anteriorly. Incise the origin of the supinator down the bone,

staying just lateral to the insertion of the biceps tendon. Complete

the exposure of the proximal radius by circumferential subperiosteal

dissection (see Fig. 3-20, inset, and Anterior Approach to the Radius in Chapter 4).

|

|

Figure 3-20

Deep surgical dissection. Make a longitudinal incision in the anterior capsule of the joint between the radial nerve and the brachialis muscle to expose the radial head and capitulum. To expose the radius further, remove the supinator muscle distally in a subperiosteal manner (inset). |

identified in the interval between the brachioradialis and brachialis

muscles before this interval is developed fully. Note that the nerve

lies anteromedial to the brachioradialis, within the fascial

compartment of that muscle. If it is being sought at the level of the

distal humerus or elbow, the intermuscular interval is the best place

to find it.

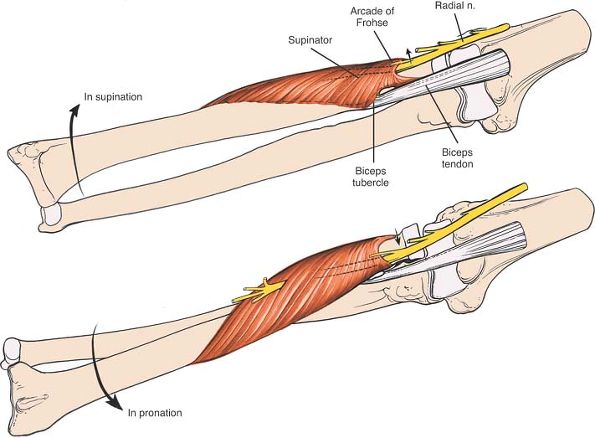

is vulnerable to injury as it winds around the neck of the radius

within the substance of the supinator muscle. To prevent damage to the

nerve, ensure that the supinator is detached from its insertion on the

radius with the forearm in supination. Do not cut through the muscle

body to expose the bone (see Anterior Approach to the Radius in Chapter 4; Fig. 3-21; see Fig. 3-33).

muscles; retract it with the medial skin flap (see Fig. 3-17).

|

|

Figure 3-21

Place the forearm in supination to move the posterior interosseous nerve lateral to the incision into the radiohumeral joint and away from the incision into the origin of the supinator muscle, protecting it. |

must be ligated so that the brachioradialis can be mobilized fully.

Ligation also reduces postoperative bleeding and avoids the risk of an

ischemic contracture developing postoperatively as a result of the

pressure caused by a postoperative bleed (see Fig. 3-19).

anterolateral approach can be extended easily into an anterolateral

approach to the distal humerus by developing the plane between the

brachialis and triceps muscles. Remember that the radial nerve crosses

the lateral border of the humerus about one handbreadth above the

lateral epicondyle. (For details, see Anterolateral Approach to the Distal Humerus.)

anterolateral approach can be extended easily to expose the entire

anterior surface of the radius by developing the plane proximally

between the brachioradialis muscle (which is supplied by the radial

nerve) and the pronator teres muscle (which is supplied by the median

nerve), and distally between the brachioradialis muscle (which is

supplied by the radial nerve) and the flexor carpi radialis muscle

(which is supplied by the median nerve). (For details, see Anterior Approach to the Radius in Chapter 4.)

surgical approach to the elbow and provides access to the neurovascular

structures that are found in the cubital fossa. Its uses include the

following:

-

Repair of lacerations to the median nerve

-

Repair of lacerations to the brachial artery

-

Repair of lacerations to the radial nerve

-

Reinsertion of the biceps tendon

-

Repair of lacerations to the biceps tendon

-

Release of posttraumatic anterior capsular contractions

-

Excision of tumor

arm in the anatomic position. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating

it for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage or

exsanguinator. Then, apply a tourniquet (see Fig. 3-14).

|

|

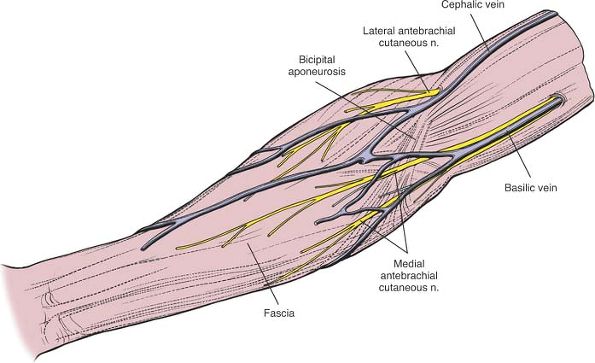

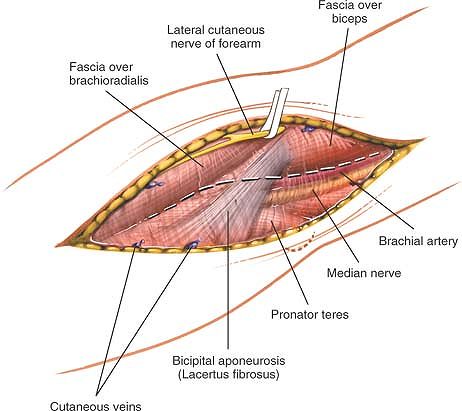

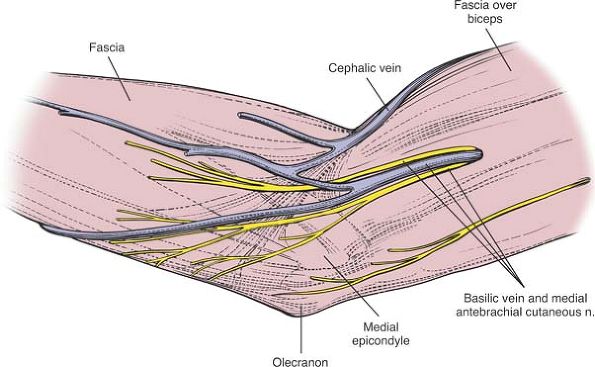

Figure 3-22 Superficial view of the elbow and forearm, showing superficial veins and nerves.

|

aspect of the elbow. Begin 5 cm above the flexion crease on the medial

side of the biceps. Curve the incision across the front of the elbow,

then complete it by incising the skin along the medial border of the

brachioradialis muscle. Curving the incision avoids crossing the

flexion crease at 90° (Figs. 3-22 and 3-23).

|

|

Figure 3-23 Incision for the anterior approach to the cubital fossa.

|

|

|

Figure 3-24

Internervous plane. Distally, the plane is between the brachioradialis (radial nerve) and the pronator teres (median nerve); proximally, it is between the brachioradialis (radial nerve) and brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve). |

plane lies between the brachioradialis muscle (which is supplied by the

radial nerve) and the pronator teres muscle (which is supplied by the

median nerve) (Fig. 3-24).

between the brachioradialis muscle (which is supplied by the radial

nerve) and the brachialis muscle (which is supplied by the

musculocutaneous nerve).

in line with the skin incision and ligate the numerous veins that cross

the elbow in this area.

branch of the musculocutaneous nerve) must be preserved. To find it,

locate the interval between the biceps tendon and the brachialis

muscle. The nerve emerges there to run down the lateral side of the

forearm subcutaneously (Fig. 3-25).

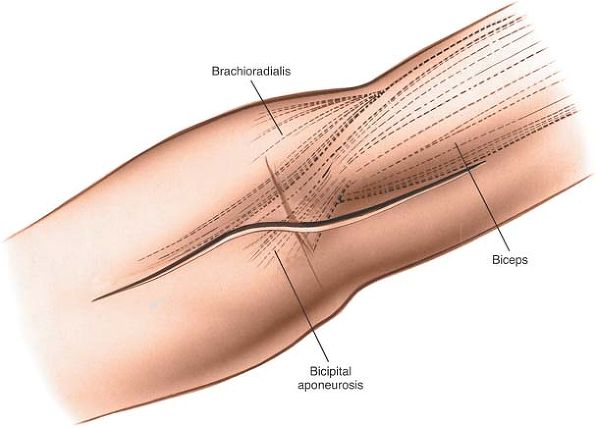

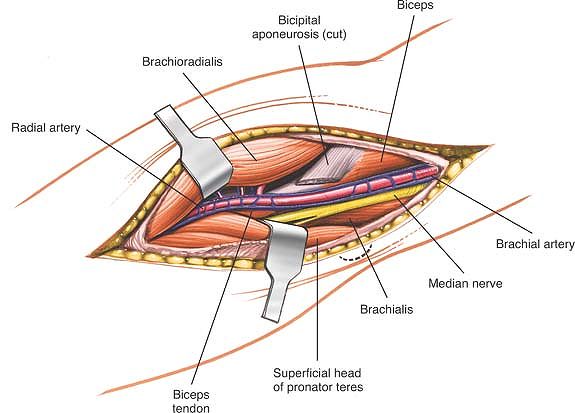

fibrosus), which is a band of fibrous tissue coming from the biceps

tendon and swinging medially across the forearm, running superficial to

the proximal part of the superficial flexor muscles (see Fig. 3-25).

Cut the aponeurosis close to its origin at the biceps tendon and

reflect it laterally. Be careful not to injure the brachial artery,

which runs immediately under the aponeurosis (Fig. 3-26).

|

|

Figure 3-25

Superficial surgical dissection. Locate the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm in the interval between the biceps tendon and the brachialis, and preserve it. |

tendon and trace it proximally to its origin from the brachial artery.

Note that both the brachial vein and the median nerve lie medial to the

artery. To identify the radial nerve, look between the brachialis and

the brachioradialis; the nerve crosses in front of the elbow joint.

relationship are the keys to operating successfully in the cubital

fossa (see Fig. 3-26).

exploration of the neurovascular structures, deep dissection is not

required. If you require access to the anterior capsule of the elbow

joint, retract the biceps and brachialis muscle medially and the

brachioradialis muscle laterally. Fully supinate the forearm and

identify the origin of the supinator muscle from the anterior aspect of

the radius. Incise the origin of this muscle and dissect it off the

bone in a subperiosteal

plane,

carefully reflecting it laterally. Take care not to insert a retractor

on the lateral aspect of the proximal radius as this may compress the

posterior interosseous nerve. The anterior capsule of the elbow joint

is now exposed and may be incised to expose the anterior aspect of the

elbow joint (Fig. 3-28).

|

|

Figure 3-26

After cutting the bicipital aponeurosis (lacertus fibrosus), identify the brachial artery. Note that the median nerve lies medial to the artery. The brachial vein, which accompanies the artery, consists of a series of small, fine vessels, the venae comitantes. |

-

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the

forearm (the sensory branch of the musculocutaneous nerve) is

vulnerable to injury in the distal fourth of the arm during incision of

the deep fascia. Pick it up in the interval between the biceps and

brachialis muscles in the arm, trace it downward, and preserve it (see Fig. 3-25). -

The radial artery lies immediately deep

to the bicipital aponeurosis; the aponeurosis must be incised carefully

to avoid damage to the artery (see Fig. 3-26). -

The posterior interosseous nerve is

vulnerable to injury as it winds round the neck of the radius within

the substance of the supinator muscle. To prevent damage to the nerve,

ensure that the supinator is detached from its insertion on the radius

with the forearm in supination (see Fig. 3-20).

the incision superiorly along the medial border of the biceps, and

incise the deep fascia in line with the incision. The brachial artery

lies immediately under the fascia, between the biceps muscle and the

underlying brachialis muscle. The medial nerve runs with the artery.

|

|

Figure 3-27

Trace the median nerve distally into the pronator teres. Incise a portion of the muscle superficial to the nerve, if necessary, to expose the nerve. The incision lies between the humeral and ulnar heads of the pronator teres. |

|

|

Figure 3-28

Retract the biceps tendon and carefully detach and retract the proximal supinator muscle to gain access to the anterior joint capsule, which may be incised to expose the elbow joint. |

median nerve as it disappears into the pronator teres muscle. Simple

retraction of the muscle may provide adequate exposure. Take care not

to cut any branches of the median nerve going to the flexor-pronator

group of muscles that pass from the medial side of the median nerve at

the level of the elbow joint. This incision lies between the humeral

and ulnar heads of the pronator teres and allows the plane between the

two heads to be developed for the distal exposure of the nerve (Fig. 3-27).

the radial artery, trace it distally as it crosses the surface of the

pronator teres, running toward the lateral side of the forearm.

Developing the plane proximally between the pronator teres and

brachioradialis muscles, and distally between the flexor carpi radialis

and brachioradialis muscles allows the artery to be followed to the

wrist.

is useful for all surgeries to the radial head, including excision of

the radial head and insertion of a prosthetic replacement.8,9

|

|

Figure 3-29 Position of the patient on the operating table.

|

annular ligament without risking damage to the posterior interosseous

nerve, avoid extending the incision to the upper part of the radial

shaft.

Exsanguinate the limb either by applying a soft rubber bandage or an

exsanguinator or by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes. Then, inflate a

tourniquet (Fig. 3-29).

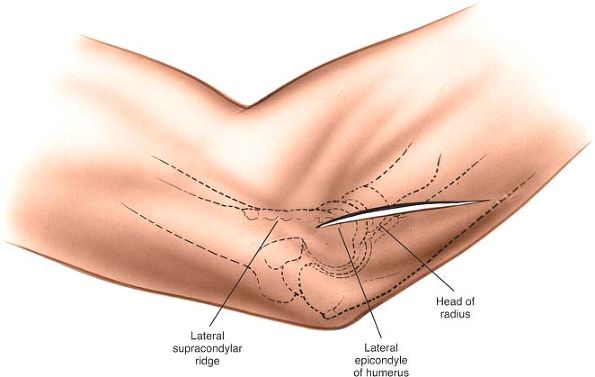

radial head lies deep within this depression. It is palpable through

the muscle mass of the wrist extensors. As the forearm is pronated and

supinated, movement of the radial head can be felt beneath the

surgeon’s fingers. In cases of fracture of the radial head, the normal

landmarks are lost because of hemorrhage and swelling. Crepitus at the

fracture site often is quite obvious and helpful in placing the

incision.

|

|

Figure 3-30 Make a longitudinal incision based proximally on the lateral humeral epicondyle.

|

posterior surface of the lateral humeral epicondyle and continuing

downward and medially to a point over the posterior border of the ulna,

about 6 cm distal to the tip of the olecranon.

proximally on the lateral humeral epicondyle. This incision follows the

skin fold and lies directly over the radial head (Fig. 3-30).

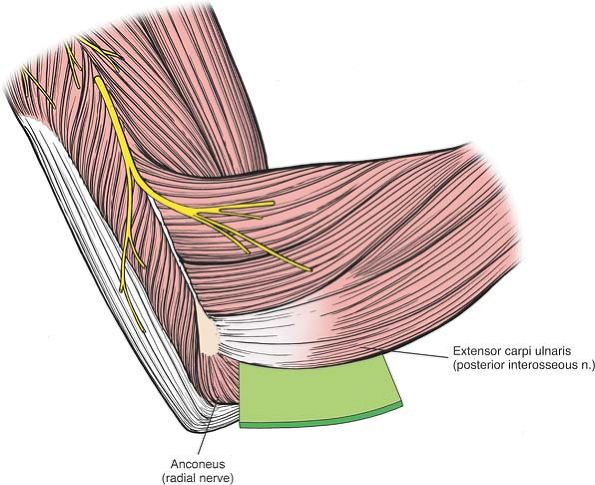

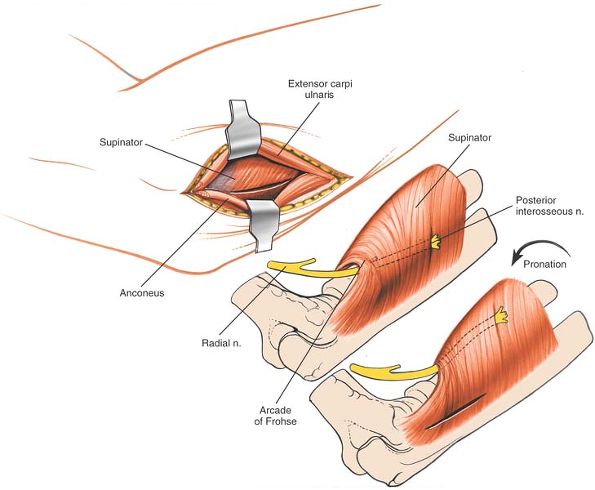

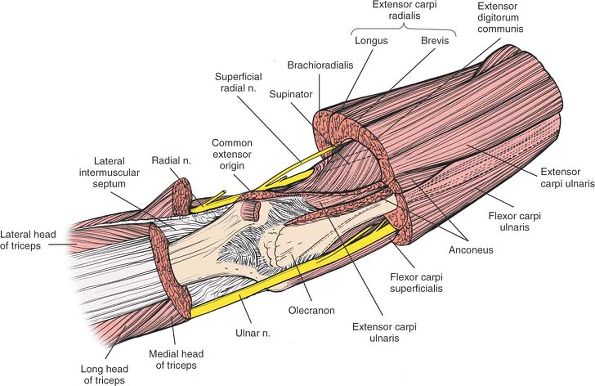

is supplied by the radial nerve, and the extensor carpi ulnaris, which

is supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve (Fig. 3-31).

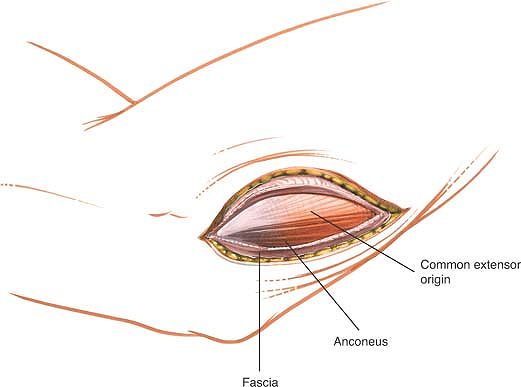

To find the interval between the extensor carpi ulnaris and the

anconeus, look distally where the plane is easy to identify;

proximally, the two muscles share a common aponeurosis (Fig. 3-32).

Detach part of the superior origin of the anconeus as it arises from

the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. Then, separate the anconeus and

extensor carpi ulnaris muscles, using retractors (Fig. 3-33).

contusion in this area, and it is difficult to identify the interval

between the extensor carpi ulnaris and anconeus muscles. In this case,

it is safe to dissect straight down onto the lateral epicondyle of the

humerus, because this structure always can be palpated easily.

|

|

Figure 3-31 The internervous plane lies between the anconeus (radial nerve) and the extensor carpi ulnaris (posterior interosseous nerve).

|

|

|

Figure 3-32 Find the interval between the extensor carpi ulnaris and the anconeus distally. Proximally, the two muscles merge.

|

|

|

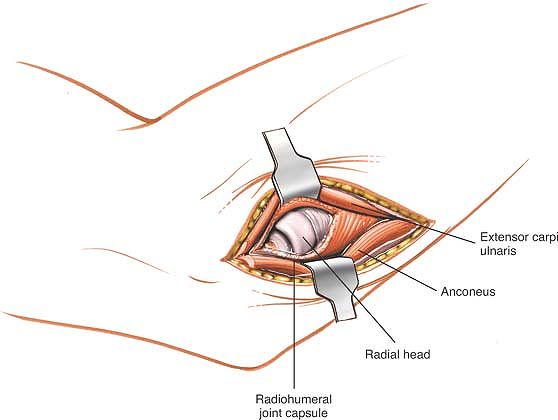

Figure 3-33

Detach the superior origin of the anconeus from the lateral epicondyle, and separate the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris. Pronation of the forearm moves the posterior interosseous nerve medially away from the operative field (insets). |

reveal the underlying capitulum, the radial head, and the annular

ligament. Do not incise the capsule too far anteriorly; the radial

nerve runs over the front of the anterolateral portion of the elbow

capsule. Do not continue the dissection below the annular ligament or

retract vigorously, distally, or anteriorly, because the posterior

interosseous nerve lies within the substance of the supinator muscle

and is vulnerable to injury (Fig. 3-34).

is in no danger as long as the dissection remains proximal to the

annular ligament. Pronation of the forearm keeps the nerve as far from

the operative field as it possibly can be (see Fig. 3-33, inset).

To ensure the safety of the nerve, take great care to place the

retractors directly on bone and be careful in their placement. Because

the posterior interosseous nerve actually may touch the bone of the

radial neck, directly opposite the bicipital tuberosity, placing

retractors behind it poses a risk.11

cutting down on the lateral supracondylar ridge. Strip the tissues off

subperiosteally both anteriorly and posteriorly to gain access to the

distal humerus and to expose the capitellum. Apply a varus force to

open up the lateral compartment of the joint. The extension is most

useful for fixing fractures internally and for removing loose bodies in

the lateral compartment of the elbow (see Anterolateral Approach to the Distal Humerus in Chapter 2).

|

|

Figure 3-34 Incise the joint capsule longitudinally to expose the capitulum and radial head.

|

lower end of the humerus and the upper end of the radius and ulna. It

communicates with the superior radioulnar joint.

-

The lateral capitulum articulates with the radial head. Its shape is reminiscent of a hemisphere.

-

The medial trochlea

articulates with the ulna. Its shape resembles a spool of thread. It

extends further distally than the capitulum, resulting in a

configuration that gives a tilt to the lower end of the humerus and

produces the “carrying angle” of the joint. The trochlea is grooved;

the groove’s boundaries are marked medially by a prominent, sharp ridge

and laterally by a lower, more blunted ridge.

collateral ligaments. The anterior and posterior ligaments are mainly

thickened sections in the capsule,

which

is exactly what would be expected from a hinge joint. The shape of the

bones that comprise the elbow joint and the presence of the strong

collateral ligaments make it difficult to explore the joint completely

without extensive dissection. Medial and lateral approaches to the

joint provide limited access unless they are extended. Complete

exposure is obtained most easily through a posterior approach, and then

only if an olecranon osteotomy is performed. Four groups of muscles

cross the elbow joint:

-

Anteriorly, the flexors of the elbow, which are supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve

-

Posteriorly, the extensor of the elbow, which is supplied by the radial nerve

-

Medially, the flexor-pronator group of

muscles (the flexors of the wrist and fingers, and the pronators of the

forearm), which are supplied by the median and ulnar nerves. They arise

from the medial epicondyle of the humerus. -

Laterally, the extensors of the wrist and

fingers, and the supinators of the forearm, which are supplied by the

radial and posterior interosseous nerves. They arise from the lateral

epicondyle of the humerus.

plane; two are internervous planes and can be explored. A third

internervous plane lies within the lateral group, as follows:

-

Between the anterior and lateral

muscle groups, which are supplied by the musculocutaneous and radial

nerves, respectively. The anterolateral approach uses the interval

between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles (see Fig. 3-16). -

Between the anterior and medial

muscle groups, which are supplied by the musculocutaneous and median

nerves, respectively. The medial approach uses the interval between the

brachialis and pronator teres muscles (see Figs. 3-8 and 3-24). -

Between two members of the lateral group:

the anconeus muscle (which is supplied by the radial nerve) and the

extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is supplied by the posterior

interosseous nerve, a major branch of the radial nerve; see Fig. 3-31). The posterolateral approach to the radial head uses this plane.

posterior groups of muscles is not an internervous plane, because both

groups are supplied by the radial nerve. The plane is useful, though,

because the radial nerve gives off its branches well proximal to the

elbow. This pseudo-internervous plane, which is used in the lateral

approach, falls in the interval between the brachioradialis and triceps

muscles (see Fig. 2-24A).

forearm, forming a triangular fossa known as the cubital fossa, which

is bordered by the pronator teres medially and the brachioradialis

laterally. The superior border of the triangle consists of an imaginary

line joining the medial and lateral epicondyle of the humerus.

front of the joint on its medial side and is covered by the bicipital

aponeurosis (lacertus fibrosus) in the cubital fossa. It disappears

between the two heads of the pronator teres muscle as it leaves the

fossa and runs down the forearm, adhering to the deep surface of the

flexor digitorum superficialis muscle (see Fig. 4-12).

front of the elbow joint in the interval between the brachialis and

brachioradialis muscles. It divides in the cubital fossa at the

radiohumeral joint line into the posterior interosseous nerve (which

enters the substance of the supinator muscle) and the superficial

radial nerve (which descends the lateral side of the forearm under

cover of the brachioradialis muscle; see Fig. 3-19).

joint in the groove on the back of the medial epicondyle, where it is

easy to palpate. The nerve enters the anterior compartment of the

forearm by passing between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris

muscle, which it supplies and where it may be entrapped. It then runs

down the forearm on the anterior surface of the flexor digitorum

profundus (see Figs. 3-40 and 3-43). In the proximal third of the forearm, it supplies the ring and little fingers.

the cubital fossa, running on the lateral side of the median nerve and

lying on the brachialis muscle. The median nerve passes under the

bicipital aponeurosis, which separates it from the median basilic vein,

a frequent site of venous puncture (see Fig. 3-35).

In the days when bleeding was a recognized form of treatment and

venesection was done with lancets rather than with needles, this site

was a frequent one used by barber surgeons. The reason this site was

preferred is because the bicipital aponeurosis protects the vital

structures of the artery and nerve, which provided these early

practitioners with a margin of safety, because their patients often

moved on insertion of the lancet. Halfway down the

cubital

fossa, the artery divides into two terminal branches: the radial and

ulnar arteries. Similar to the median nerve, the artery may be damaged

in supracondylar fractures of the humerus (see Fig. 3-26).

medial to the biceps tendon before turning anteriorly, lying on the

supinator muscle and the insertion of the pronator teres muscle. In the

upper forearm, it lies under the brachioradialis muscle (see Fig. 4-11).

disappears from the cubital fossa by passing deep to the deep head of

the pronator teres, the muscle that separates it from the median nerve

(see Fig. 4-13).

-

The pronator teres

-

The flexor carpi radialis

-

The flexor digitorum superficialis

-

The palmaris longus

-

The flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 3-36)

the flexor carpi ulnaris is supplied by the ulnar nerve. The pronator

teres, the most proximal muscle, forms the medial border of the cubital

fossa.

|

|

Figure 3-35 Medial view of the elbow. Note the sensory nerves and veins on the medial side of the elbow joint.

|

of the medial epicondyle. They can be retracted only a short distance

because the median nerve, passing through the pronator teres muscle,

“anchors” the group and prevents distal retraction (Figs. 3-35, 3-36, 3-37, 3-38 and 3-39).

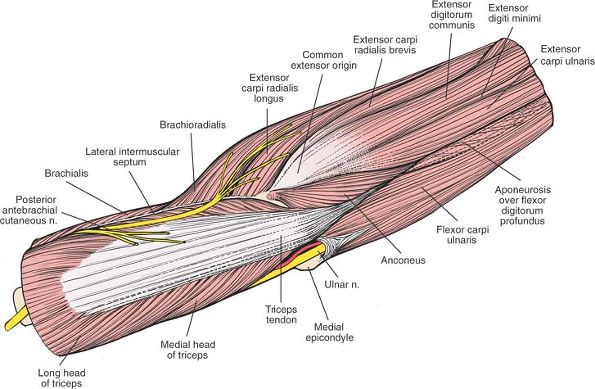

-

The mobile wad of three muscles,

consisting of the brachioradialis, the extensor carpi radialis longus,

and the extensor carpi radialis brevis -

Four muscles arising from the common

extensor origin: the extensor digitorum communis, the extensor digiti

minimi, the extensor carpi ulnaris, and the anconeus

muscle of the elbow; its function is unclear. Its more distal fibers

run almost vertically and act as a weak extensor of the elbow, whereas

its proximal fibers are almost horizontal and

adduct

and rotate the ulna. This unlikely movement occurs to a slight degree

at the elbow. Electromyographic studies suggest that the muscle is most

active during extension,12

but it probably functions more as a stabilizer while other muscles act

on the elbow as prime movers, functioning in much the same way as does

the rotator cuff in the shoulder.

|

|

Figure 3-36

The five muscles of the forearm have a common flexor origin on the medial epicondyle. All five are supplied by the median nerve. The ulnar nerve passes between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The median nerve runs beneath the bicipital aponeurosis. |

|

|

Figure 3-37

The flexor-pronator group has been resected, revealing the course of the ulnar nerve as it runs around the medial epicondyle, passing distally before entering the plane between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum profundus. |

|

|

Figure 3-38

The flexor muscles have been resected further. The medial epicondyle has been subjected to osteotomy. Distally, the ulnar nerve crosses the forearm between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the profundus. The median nerve enters the forearm between the two heads of the pronator teres, lying on the tendon of the brachialis. |

|

|

Figure 3-39 The joint capsule has been opened. The brachialis is elevated from the capsule.

|

forms one boundary of the internervous plane that is used in the

posterolateral approach to the radial head.

cross the anterior aspect of the elbow joint. Both are supplied by the

musculocutaneous nerve, which runs between the biceps and the

brachialis in the upper arm. In front of the elbow, they diverge; the

biceps runs laterally to the bicipital tuberosity of the radius, and

the brachialis runs medially to the coronoid process of the ulna.

flat tendon, which also overlies the brachialis. The tendon rotates so

that its anterior surface faces laterally as it passes between the two

bones of the forearm before inserting into the back of the radius at

the bicipital tuberosity. A bursa separates the tendon from the

anterior part of the tuberosity.

|

|

Figure 3-40

Superficial view of the posterior aspect of the elbow. The triangular aponeurosis of the triceps runs down to its triangular insertion into the ulna. The ulnar nerve lies in its groove on the posterior aspect of the elbow. The brachial cutaneous nerve crosses the intermuscular septum on the posterior aspect of the elbow. Anconeus. Origin. Lateral epicondyle of humerus and posterior joint capsule of elbow. Insertion. Lateral side of olecranon and posterior surface of ulna. Action. Extensor of elbow. Nerve supply. Radial nerve.

|

cubital fossa. It separates superficial nerves and vessels from deep

ones. Lying superficial are the median cephalic vein, the median

basilic vein, and the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm. Lying deep

are the median nerve and the brachial artery.

and brachial vein can be remembered easily through the mnemonic “VAN”

(vein, artery, nerve), which labels the structures from the lateral to

the medial aspect. They all pass medial to the biceps tendon under the

lacertus fibrosus (see Fig. 3-27).

|

|

Figure 3-41

The distal part of the triceps, the origins of the flexors and flexor carpi ulnaris, and the extensor tendons have been resected. The ulnar nerve enters the plane between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. On the radial side, the radial nerve lies anterior to the intermuscular septum, between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles. |

|

|

Figure 3-42

The insertion of the anconeus, the origin of the extensor carpi ulnaris, and the common extensor origin are revealed. The radial nerve divides into its main continuation, the posterior interosseous nerve, as it enters the supinator muscle through the arcade of Frohse. The superficial branch (sensory branch) of the radial nerve enters the undersurface of the brachioradialis. The ulnar nerve gives off its branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris immediately after it passes around the groove between the olecranon and the medial epicondyle. |

|

|

Figure 3-43

The supinator muscle has been resected, revealing the distal course of the posterior interosseous nerve through its distal portion. The annular portion of the radiohumeral ligament is defined clearly. |

Boer P, Stanley D: Surgical approaches to the elbow. In: Stanley D, Kay

N, eds. Surgery of the elbow: practical and scientific aspects. London,

Arnold, 1998

AB, Jaeger SH, Larochelle D: Comminuted fractures of the radial head:

the role of silicone implant replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint

Surg [Am] 63:1039, 1981

JCH, Ellis BW: Vulnerability of the posterior interosseous nerve during

radial head excision. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 53:320, 1971