The Humerus

generally involve the open reduction and internal fixation of

fractures. All approaches to the humerus are potentially dangerous

because the major nerves and vessels at this site run much closer to

the bone than they do elsewhere in the body; the axillary, radial, and

ulnar nerves all have a direct relationship to the humerus. Of these

structures, the radial nerve is at greatest risk during exposure of the

humeral shaft (see Fig. 2-33).

chapter: the anterior approach to the humerus, the minimal access

anterior approach to the humeral shaft, the anterolateral approach to

the distal humerus, the posterior approach and the lateral approach to

the distal humerus, and the minimal access approach for humeral

nailing. Of these, the anterior and posterior approaches are the most

versatile, providing access to large portions of bone. The

anterolateral approach to the distal humerus is extensile both

proximally and distally, but this facility rarely is required. The

lateral approach to the distal humerus is a strictly local approach to

the common extensor origin and adjacent structures. Because the key

surgical structure of the area (the radial nerve) courses down the arm

in both the anterior and posterior compartments, the surgical anatomy

of the humerus is described in a single section of this chapter,

immediately after the description of the operative approaches.

Normally, only a portion of the approach is needed for any one

procedure. As in all approaches to the humerus, the radial nerve is the

structure at greatest risk during surgery.

-

Internal fixation of fractures of the humerus

-

Osteotomy of the humerus

-

Biopsy and resection of bone tumors

-

Treatment of osteomyelitis

|

|

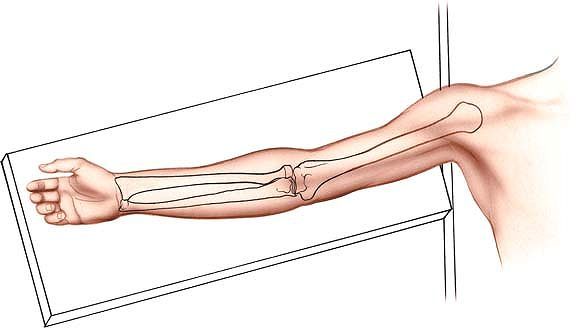

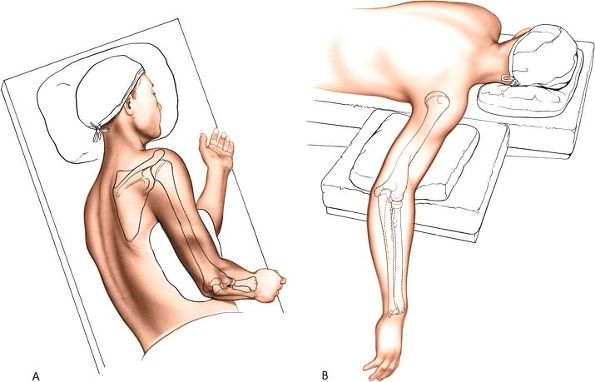

Figure 2-1 Place the patient supine on the operating table. Place his or her arm on an arm board and abduct the arm about 60°.

|

the arm on an arm board, abducted about 60°. Tilt the patient away from

the affected arm to reduce bleeding. Most surgeons prefer to sit facing

the patient’s axilla, with the surgical assistant on the opposite side

of the arm. Do not use a tourniquet; it will only get in the way (Fig. 2-1).

|

|

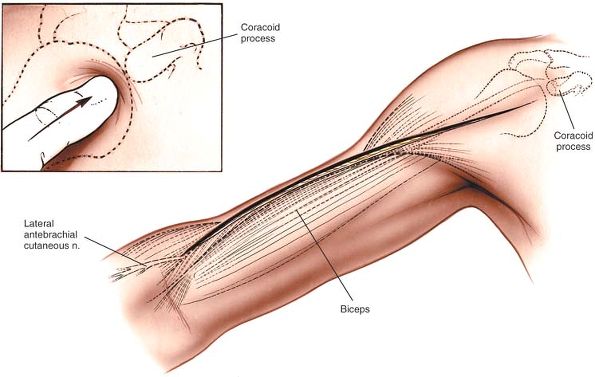

Figure 2-2

For an anterior approach, make a longitudinal incision from the tip of the coracoid process distally in line with the deltopectoral groove and continue along the lateral aspect of the shaft of the humerus. Extend the incision as far distally as necessary, stopping about 5 cm above the flexion crease of the elbow. Palpate the coracoid process in a lateral to medial direction (inset). |

as it crosses the shoulder and runs down the arm. The lateral border of

its freely moving muscular belly lies on the anterior surface of the

arm.

coracoid process of the scapula. Run it distally and laterally in the

line of the deltopectoral groove to the insertion of the deltoid muscle

on the lateral aspect of the humerus, about halfway down its shaft.

From there, the incision should be continued distally as far as

necessary, following the lateral border of the biceps muscle. The

incision should be stopped about 5 cm above the flexion crease of the

elbow (see Fig. 2-2).

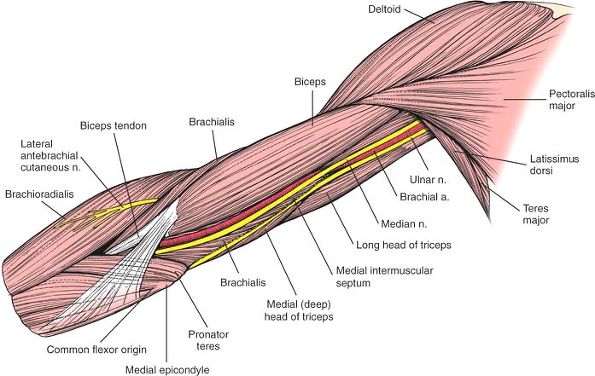

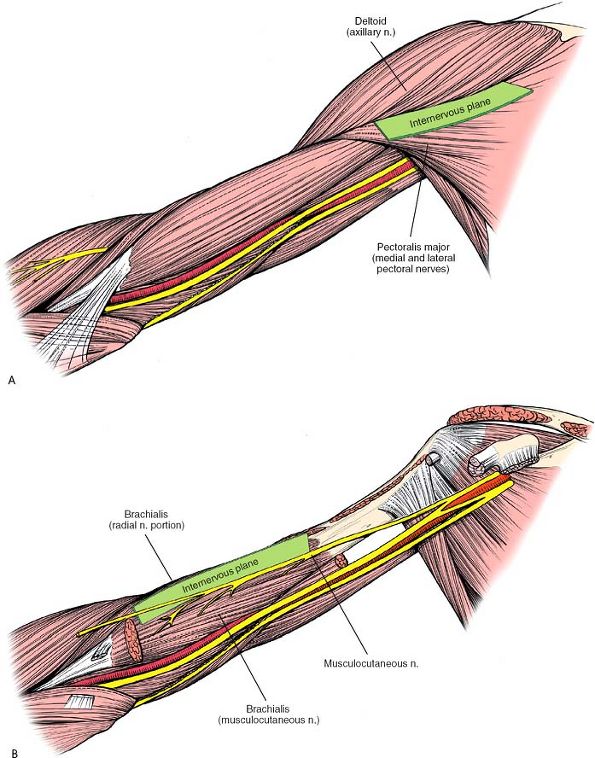

Proximally, the plane lies between the deltoid muscle (which is

supplied by the axillary nerve) and the pectoralis major muscle (which

is supplied by the medial and lateral pectoral nerves). Distally, the

plane lies between the medial fibers of the brachialis muscle (which

are supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve) medially and the lateral

fibers of the brachialis muscle (which are supplied by the radial

nerve) laterally (Fig. 2-3B).

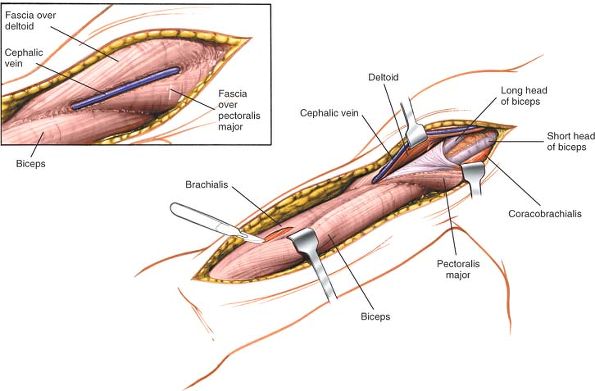

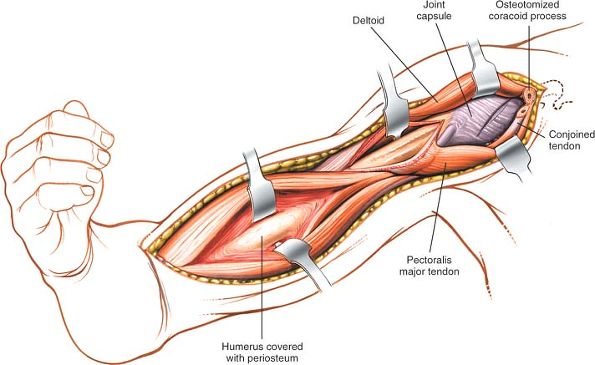

and separate the two muscles, retracting the cephalic vein either

medially with the pectoralis major or laterally with the deltoid,

whichever is easier. Develop the muscular interval distally down to the

insertion of the deltoid into the

deltoid tuberosity and the insertion of the pectoralis major into the lateral lip of the bicipital groove (Fig. 2-4).

Take care when retracting the deltoid; overzealous use of the retractor

may paralyze the anterior half of the muscle by causing a compression

injury to the axillary nerve.

|

|

Figure 2-3 Internervous plane. (A) Proximally, the plane lies between the deltoid (axillary nerve) and the pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves). (B)

Distally, the plane lies between the medial fibers of the brachialis (musculocutaneous nerve) medially and the lateral fibers of the brachialis (radial nerve) laterally. |

|

|

Figure 2-4 Identify the deltopectoral groove, using the cephalic vein as a guide (inset).

Develop the muscular interval down to the insertion of the deltoid into the deltoid tuberosity and the insertion of the pectoralis major into the lateral bicipital groove. Distally, incise the deep fascia in line with the skin incision to identify the interval between the biceps brachii and the brachialis. |

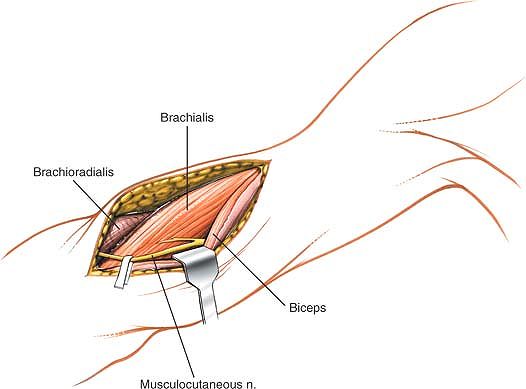

incision. Identify the muscular interval between the biceps brachii and

the brachialis. Develop the interval by retracting the biceps medially.

Beneath it lies the anterior aspect of the brachialis, which cloaks the

humeral shaft (Fig. 2-5; see Fig. 2-4).

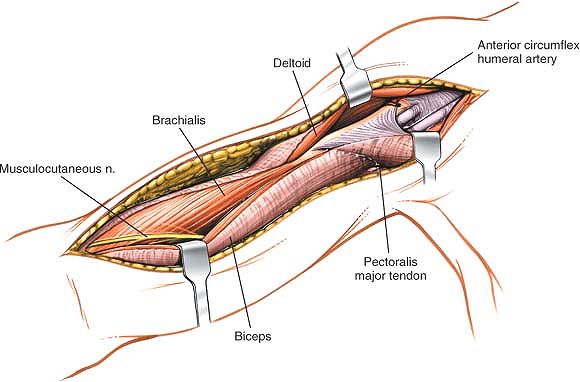

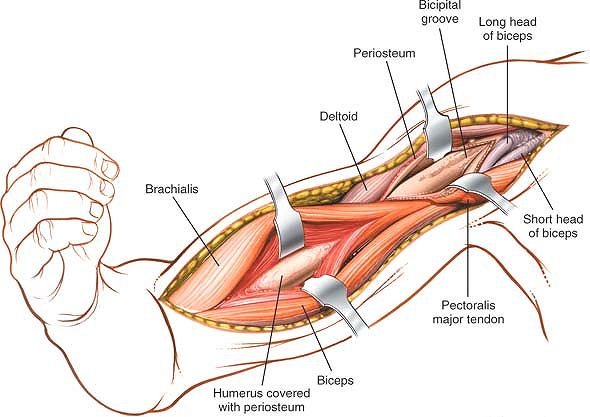

incise the periosteum longitudinally just lateral to the insertion of

the tendon of the pectoralis major. Continue the incision proximally,

staying lateral to the tendon of the long head of the biceps. The

anterior circumflex humeral artery crosses the field of dissection in a

medial to lateral direction and must be ligated (see Fig. 2-5).

To expose the bone fully, you may need to detach part or all of the

insertion of the pectoralis major muscle from the lateral lip of the

bicipital groove of the humerus (Fig. 2-6).

This must be done subperiosteally. Only detach the minimum amount of

soft tissue to allow accurate visualization and reduction of the

fracture. Try to preserve as much soft-tissue attachment as possible.

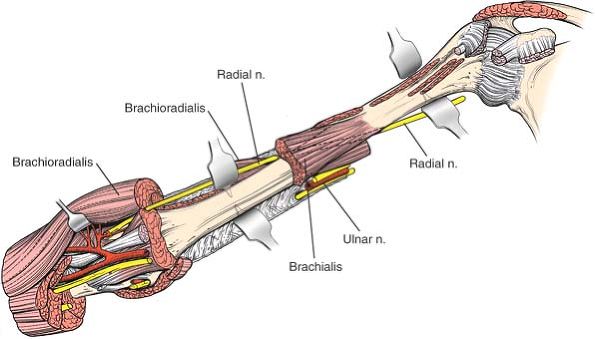

If you need to dissect further around the bone, this dissection should

remain in a strictly subperiosteal plane to avoid damage to the radial

nerve, which lies in the spiral groove of the humerus and crosses the

back of the middle third of the bone in a medial to lateral direction (Fig. 2-7).

comminuted fractures, the head and anatomic neck of the humerus may

need to be exposed. To accomplish this, the subscapularis muscle must

be divided, with care taken to coagulate the triad of vessels that runs

along the lower border of that muscle (Fig. 2-8; see Fig. 1-20). Frequently, however, the lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis tendon

forms a separate fracture fragment, rendering division of the subscapularis tendon unnecessarily.

|

|

Figure 2-5

Retract the biceps medially, being careful to identify the musculocutaneous nerve. Proximally, identify the anterior circumflex humeral artery as it crosses the field of dissection in a medial to lateral direction. |

|

|

Figure 2-6

Proximally, detach the insertion of the pectoralis major from the lateral bicipital groove and then continue dissection subperiosteally to expose the upper portion of the humerus. Distally, split the fibers of the brachialis to expose the periosteum of the anterior humerus. Incise the periosteum, and strip the brachialis off the bone. Flexion of the elbow will take tension off the brachialis, making the exposure easier. |

|

|

Figure 2-7

The radial nerve is vulnerable at two points as it courses along the humerus: one, in the spiral groove, and two, as it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum to run between the brachioradialis and the brachialis. |

|

|

Figure 2-8

Proximal extension of the exposure. Using the deltopectoral interval, cut the tip of the coracoid and incise the subscapularis to provide an anterior approach to the shoulder. |

its midline to expose the periosteum on the anterior surface of the

humeral shaft. Strip the brachialis off the anterior surface of the

bone. Try to preserve as much soft-tissue attachment as possible. To

make the task easier, flex the elbow to take tension off the

brachialis. The bone is now exposed (see Fig. 2-6).

-

In the spiral groove on the back of the middle third of the humerus, not straying onto the posterior surface of the bone (see Figs. 2-7 and 2-37).

Remember that the radial nerve may be damaged by drills, taps, or

screws that are inserted anteroposteriorly when anterior plates are

being applied in the middle third of the bone. -

In the anterior compartment of the distal

third of the arm. At this point, the nerve has pierced the lateral

intermuscular septum and lies between the brachioradialis and

brachialis muscles. Note that this plane is oblique and not vertical

(see Fig. 2-34). To avoid damaging the nerve,

split the brachialis along its midline; the lateral portion of the

muscle then serves as a cushion between the retractors that are being

used in the exposure and the nerve itself (see Figs. 2-7 and 2-37).

runs on the underside of the deltoid muscle, may be damaged as a result

of a compression injury caused by overly vigorous retraction of the

muscle. Care should be taken when the retractors are being positioned

on the deltoid to avoid injuring the nerve (see Fig. 2-4).

cross the operative field in the interval between the pectoralis major

and deltoid muscles in the upper third of the arm. Because cutting

these vessels cannot be avoided, they should be ligated or subjected to

diathermy (see Figs. 2-5 and 2-6).

Because the anterior approach uses the deltopectoral interval, its

upper end can be modified easily into an anterior approach to the

shoulder (see Fig. 2-8).

utilizes two soft-tissue windows, proximal and distal. The use of this

approach is almost exclusively for internal fixation of fractures of

the humerus. The advantage of this approach is the preservation of the

blood supply to the fracture zone. The disadvantage is that the

fracture is not exposed, which makes reduction more difficult to

achieve and assess.

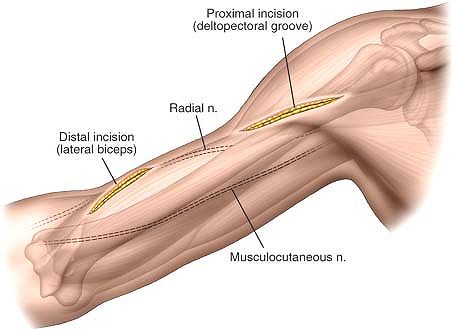

below the coracoid process running down the arm in the line of the

deltopectoral groove. Make a second 5- to 7-cm longitudinal incision

overlying the lateral border of the biceps brachii in the distal third

of the arm. The positioning of the incision is determined by the site

of the fracture.

|

|

Figure 2-9

Proximally make a 6- to 8-cm longitudinal incision based on the coracoid process. Distally make a 6- to 8-cm incision overlying the lateral border of the biceps brachii. The precise length and positioning of the incisions depends on the site of the pathology and the implant used to treat it. |

utilizes the plane between the deltoid muscle (axillary nerve) and the

pectoralis major muscle (lateral and medial pectoral nerves). Distally,

the plane lies between the medial half of the brachialis muscle

supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve in the lateral half of the

brachialis muscle supplied by the radial nerve (see Figs. 2-3 and 2-4).

vein as a guide. Separate the two muscles. This can usually be done

with blunt dissection (see Fig. 2-4).

|

|

Figure 2-10

Deepen the incision in the line of the skin incision. Proximally expose the deltopectoral interval. Distally expose the lateral border of the biceps brachii. |

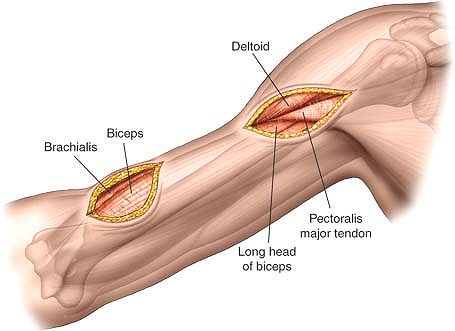

skin incision and identify the muscular interval between the biceps

brachii and the brachialis. Develop this interval by retracting the

biceps medially and identify the brachialis muscle covering the

anterior humeral shaft (Figs. 2-10 and 2-11).

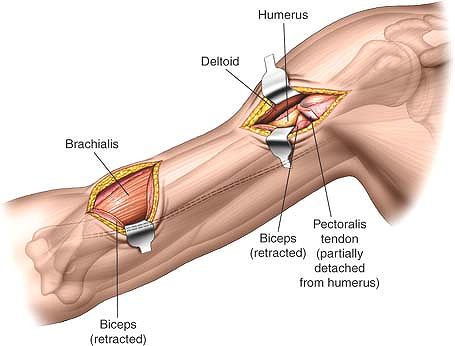

tendon of the long head of the biceps. For access to some of the bone

for plate application, you will now need to detach part or all of the

insertion of pectoralis major and the insertion of the deltoid.

|

|

Figure 2-11

Proximally develop the interval between the pectoralis major muscle and the deltoid to expose the underlying bone. Part of the tendon of pectoralis major may need to be detached from the bone. |

develop an epi-periosteal plane between the deep surface of the

brachialis and the periosteum covering the anterior surface of the

humerus. Try to preserve as much of the soft tissue as possible. To

make your task easier, flex the elbow to decrease the tension on the

brachialis muscle.

|

|

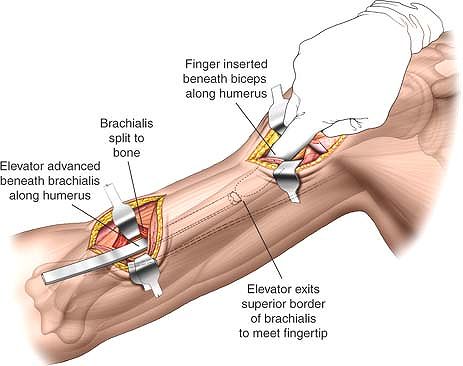

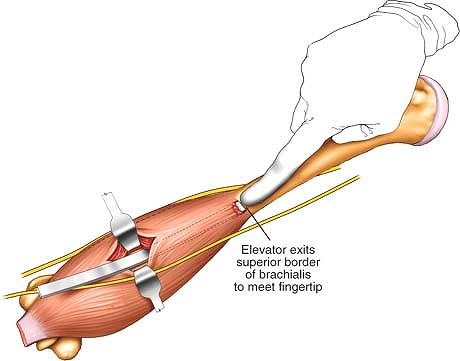

Figure 2-12

Distally retract the belly of the biceps brachii muscle medially to expose the anterior surface of the brachialis muscle. Split the brachialis longitudinally in the line of its fibers to expose the anterior surface of the humerus. Next, develop an epi-periosteal plane on the anterior surface of the bone. Proximally develop an epi-periosteal plane on the anterior surface of the humerus using finger dissection. |

plane on the anterior surface of the humerus using a blunt elevator.

Begin distally and stick closely to the anterior surface of the bone.

You may also need to develop this plane working distally through the

proximal window (Figs. 2-12 and 2-13).

|

|

Figure 2-13 Connect the proximal and distal windows by blunt dissection in an epi-periosteal plane on the anterior surface of the humerus.

|

to the surgical approach in the distal window, lying between the

lateral border of the brachialis and the brachioradialis.

and its distal branch, the lateral anti-brachial cutaneous nerve, lie

medial to the brachialis and the distal window. To avoid damage to

either nerve make sure that the brachialis is split in its mid line.

cross the operative field in the interval between the pectoralis major

and the deltoid muscle in the upper third of the arm. These structures

need to be identified while developing the plane and, if possible,

avoided.

converted into the anterior approach to the humerus by connecting the

two skin incisions. Splitting brachialis completes the exposure.

the humerus. Its major advantage over the brachialis-splitting anterior

approach is that it can be extended both distally and proximally,

whereas the brachialis-splitting approach cannot be extended distally.

Its uses include the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the distal half of the humerus, especially the Holstein Lewis fracture

-

Exploration of the radial nerve in the distal part of the arm

the arm lying on an arm board and abducted about 60°. Exsanguinate the

limb either by elevating it for 3 minutes or by applying a soft rubber

bandage; then apply a tourniquet in as high a position as possible (see

Fig. 2-1).

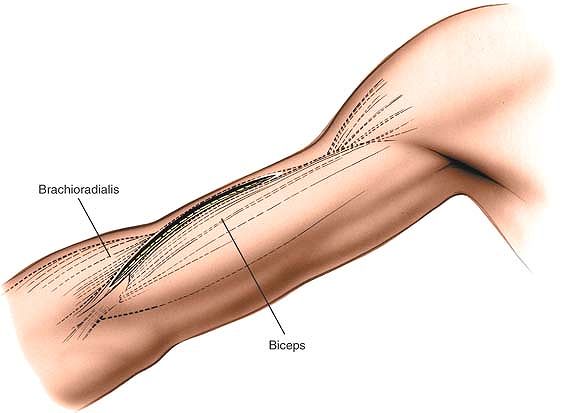

border of the biceps, starting about 10 cm proximal to the flexion

crease of the elbow. Follow the contour of the muscle, ending the

incision just above the flexion crease of the elbow (Fig. 2-14).

brachioradialis muscle and the lateral half of the brachialis muscle

are supplied by the radial nerve proximal to the area of the incision.

Proximal extension of the incision may denervate part of the

brachialis, but this is of no clinical significance, because the radial

nerve supply to the brachialis is minor and, probably, only

proprioceptive. For this reason, the plane is both safe and extensile.

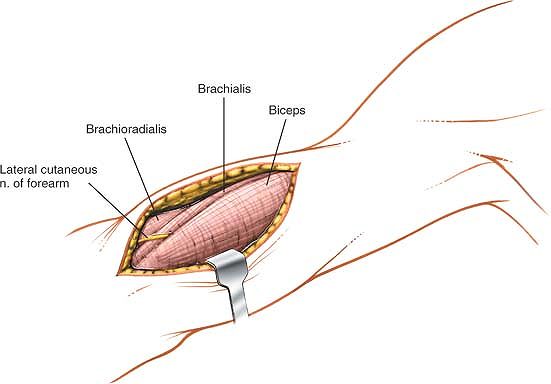

Care should be taken during dissection down to the deep fascia; the

lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm runs roughly in the line of

approach and should be retracted clear of the incision, in conjunction

with the biceps (Figs. 2-15 and 2-16).

|

|

Figure 2-14

The incision for the anterior lateral approach. Make a curved longitudinal incision over the lateral border of the biceps, starting about 10 cm proximal to the flexion crease of the elbow. End the incision just above the flexion crease. |

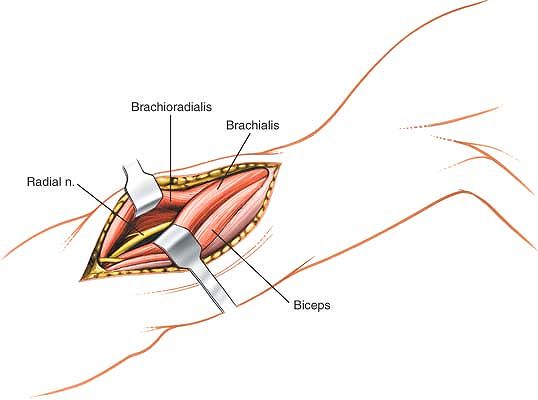

Next, identify the interval between these muscles just above the elbow,

incise the deep fascia over them in line with the intermuscular

interval, and develop the intermuscular plane (Fig. 2-17).

Find the radial nerve between the two muscles at the level of the elbow

joint by exploring this oblique intermuscular plane gently with a

finger. This is the easiest point at which to find the nerve. (The

elbow is the point at which the radial nerve should be identified in

all surgery performed in this general area.) Take care not to stretch

the radial nerve while manipulating fractures in this area to obtain a

reduction. Retract the brachioradialis laterally and the brachialis and

biceps medially. Trace the radial nerve proximally until it pierces the

lateral intermuscular septum.

|

|

Figure 2-15

There is no true internervous plane, but both the brachioradialis and the lateral half of the brachialis are supplied well proximal to the incision by the radial nerve. The sensory branch of the musculocutaneous nerve, the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve), is seen emerging between the biceps and brachialis muscles. |

|

|

Figure 2-16

Retract the biceps medially. Identify the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (the sensory continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve) and retract it with the biceps. Identify the interval between the brachialis and the brachioradialis. |

|

|

Figure 2-17

Develop the intermuscular plane between the brachialis and the brachioradialis. Identify the radial nerve between the two muscles. Retract the brachioradialis laterally and the brachialis and biceps medially. Then trace the radial nerve proximally until it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum. |

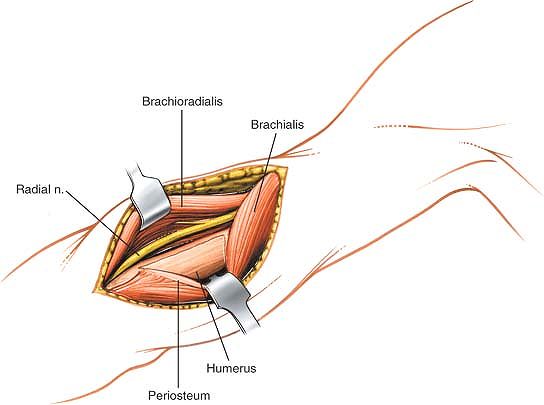

medial side, incise the lateral border of the brachialis muscle

longitudinally, cutting down to bone (Fig. 2-18).

Incise the periosteum of the anterolateral aspect of the humerus

longitudinally and retract the brachialis medially, lifting it off the

anterior aspect of the bone by subperiosteal dissection. The anterior

aspect of the distal humeral shaft now is exposed.

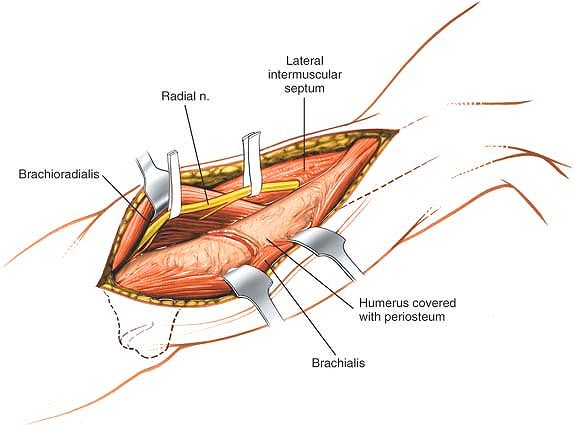

incision can be extended proximally (although this rarely is required)

by developing the plane between the brachialis medially and the lateral

head of the triceps posterolaterally. Stripping brachialis from the

front of the anterior aspect of the humerus exposes the bone. Care must

be taken, however, if the dissection is taken further posteriorly as

posterior dissection may endanger the radial nerve as it passes in the

spiral groove. If the approach is therefore extended posteriorly, a

subperiosteal plane must be used. The disadvantage of soft-tissue

stripping of the bone is in this case outweighed by the need to reduce

the risk of damage to the radial nerve (Fig. 2-19).

anterolateral approach may be extended into an anterior approach to the

elbow by continuing the skin incision distally and developing a plane

between the brachioradialis muscle (which is supplied by the radial

nerve) and the pronator teres muscle (which is supplied by the median

nerve). Care should be taken to avoid the lateral cutaneous nerve of

the forearm (the continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve), which

emerges along the lateral side of the biceps tendon (see Anterolateral Approach in Chapter 3; see Figs. 3-15 and 3-16).

|

|

Figure 2-18

Incise the periosteum of the anterolateral aspect of the humerus, and retract the brachialis and the periosteum medially to expose the anterior aspect of the distal shaft of the humerus. |

|

|

Figure 2-19

The incision can be extended proximally by developing the plane between the brachialis and the lateral head of the triceps. The radial nerve is seen piercing the intermuscular septum. Posterior dissection may endanger the nerve as it passes through the spiral groove unless the dissection is kept below the periosteum. |

classically extensile, providing excellent access to the lower three

fourths of the posterior aspect of the humerus.1

As is true for all other approaches to the humerus, the posterior

approach is complicated by the vulnerability of the radial nerve, which

spirals around the back of the bone. The uses of this surgical approach

include the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

fractures of the humerus. In fractures in which the radial nerve is

transected (classically displaced transverse fractures of the mid shaft

of the humerus), this incision exposes the nerve as it traverses the

back of the humerus. -

Treatment of osteomyelitis

-

Biopsy and excision of tumors

-

Treatment of nonunion of fractures

-

Exploration of the radial nerve in the spiral groove

-

Insertion of retrograde humeral nails

surgery: a lateral position on the operating table with the affected

side uppermost (Fig. 2-20A) or a prone position on the operating table with the arm abducted 90° (Fig. 2-20B).

A sandbag should be placed under the shoulder of the side to be

operated on, and the elbow should be allowed to bend and the forearm to

hang over the side of the table. A tourniquet should not be used

because it will get in the way.

|

|

Figure 2-20 Position of the patient for the approach to the upper arm in either the (A) lateral or (B) prone position.

|

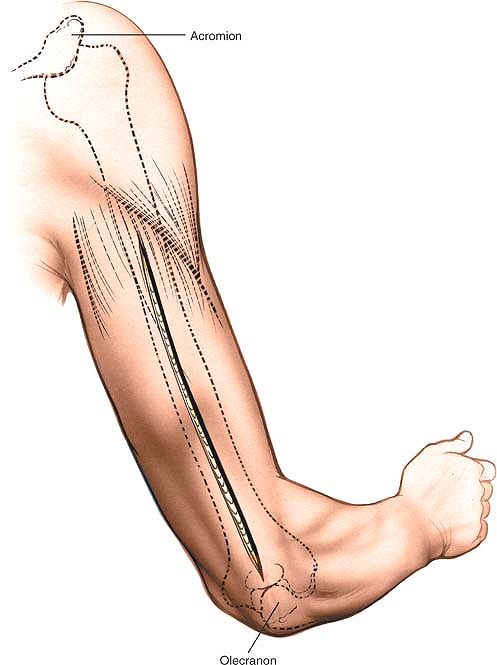

be palpated at the distal end of the posterior aspect of the arm.

Precise palpation is difficult, because the fossa is filled with fat

and covered by a portion of the triceps muscle and aponeurosis. The

fossa is filled by the olecranon when the elbow is extended.

posterior aspect of the arm, from 8 cm below the acromion to the

olecranon fossa (Fig. 2-21).

|

|

Figure 2-21

Make a longitudinal incision in the midline of the posterior aspect of the arm, from 8 cm below the acromion to the olecranon fossa. |

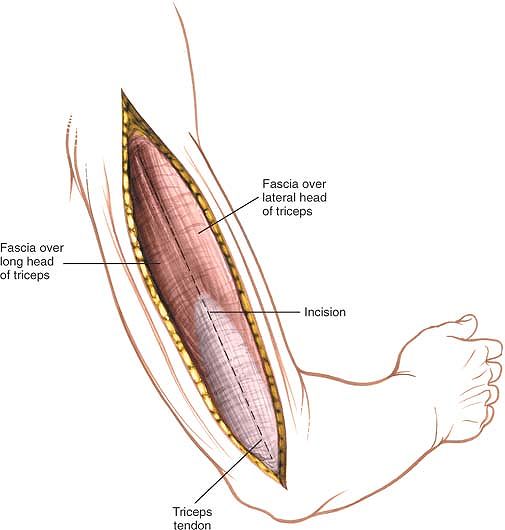

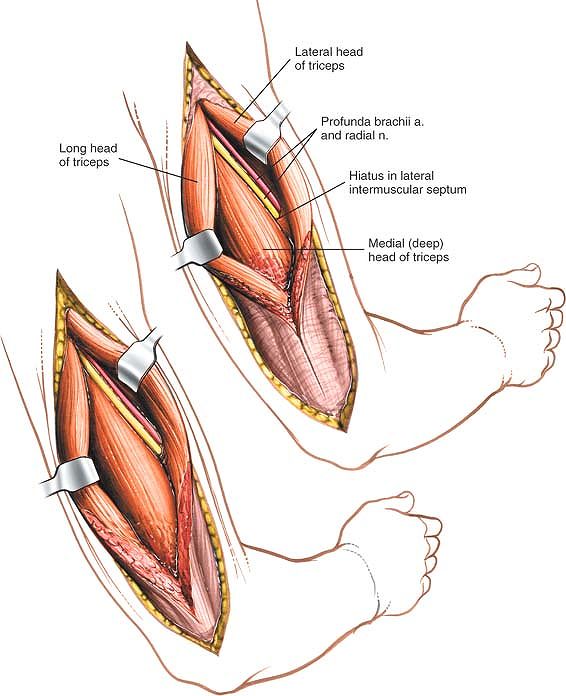

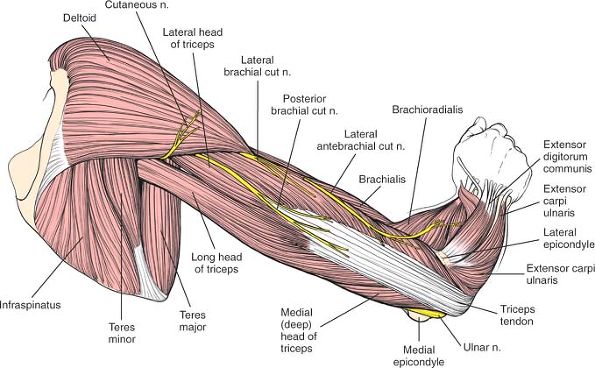

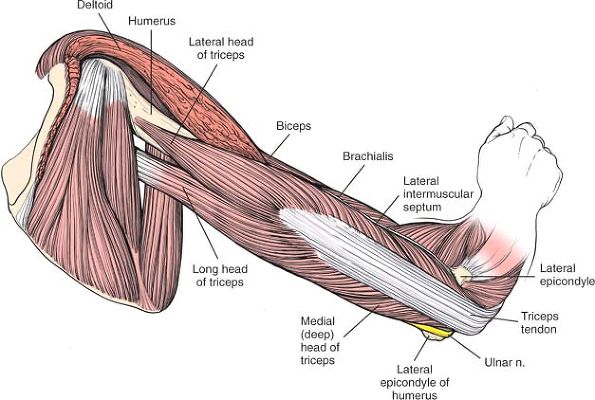

separating the heads of the triceps brachii muscle, all of which are

supplied by the radial nerve. Because the nerve branches enter the

muscle heads relatively near their origin and run down the arm in the

muscle’s substance, splitting the muscle longitudinally does not

denervate any part of it. In addition, the medial head (which is the

deepest head) has a dual nerve supply consisting of the radial and

ulnar nerves; splitting the medial head longitudinally does not

denervate either half (see Fig. 2-41).

the anatomy of the triceps muscle. This muscle has two layers. The

outer layer consists of two heads: the lateral head arises from the

lateral lip of the spiral groove, and the long head arises from the

infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula. The inner layer consists of the

third head, the medial (or deep) head, which arises from the whole

width of the posterior aspect of the humerus below the spiral groove

all the way down to the distal fourth of the bone. The spiral groove

contains the radial nerve; thus, the radial nerve actually separates

the origins of the lateral and medial heads (see Fig. 2-41).

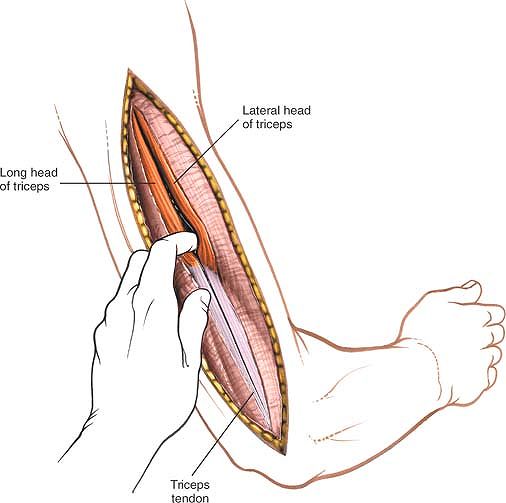

begin proximally, above the point at which the two heads fuse to form a

common tendon (Fig. 2-23). Proximally, develop

this interval between the heads by blunt dissection, retracting the

lateral head laterally and the long head medially. Distally, the muscle

will need to be divided by sharp dissection along the line of the skin incision (Fig. 2-24; see Fig. 2-40). Many small blood vessels cross the muscle at this level; these need to be coagulated individually.

|

|

Figure 2-22 Incise the deep fascia of the arm in line with the skin incision.

|

|

|

Figure 2-23 Identify the gap between the lateral and long heads of the triceps muscle.

|

|

|

Figure 2-24

Proximally develop the interval between the two heads by blunt dissection, retracting the lateral head laterally and the long head medially. Distally split their common tendon along the line of the skin incision by sharp dissection. Identify the radial nerve and the accompanying profunda brachii artery. |

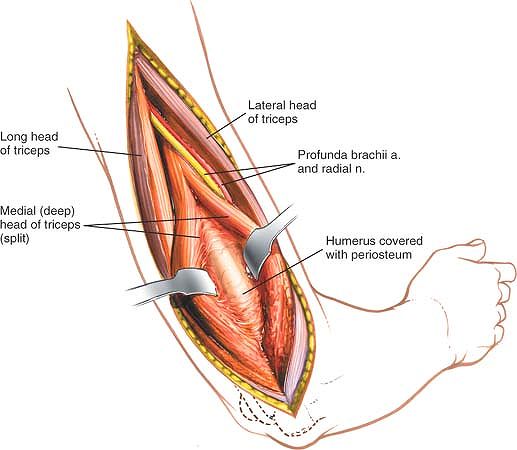

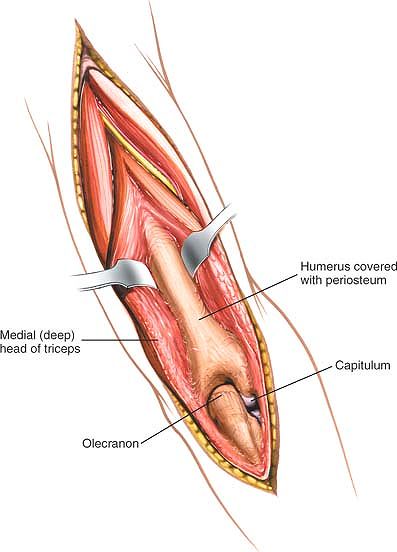

other two heads; the radial nerve runs just proximal to it in the

spiral groove (see Fig. 2-24). Incise the

medial head in the midline, continuing the dissection down to the

periosteum of the humerus. Then, strip the muscle off the bone by

epi-periosteal dissection (Fig. 2-25). The

plane of operation must remain in a epi-periosteal location to avoid

damaging the ulnar nerve, which pierces the medial intermuscular septum

as it passes in an anterior to posterior direction in the lower third

of the arm (see Figs. 2-25 and 2-42). Detach as little soft tissue as possible to preserve blood supply to the zone of injury.

|

|

Figure 2-25

Incise the medial head of the triceps in the midline. Strip the muscle off the bone subperiosteally. The radial nerve, which runs just proximal to the origin of the muscle in the spiral groove, must be identified and preserved. The muscle must be stripped from the bone below the level of the periosteum to avoid damaging the ulnar nerve, which pierces the medial intermuscular septum. Preserve as much soft-tissue attachment to the bone as possible. |

After it is identified, however, the nerve is safe. To avoid problems,

never continue the dissection down to bone in the proximal two thirds

of the arm until the nerve has been identified positively (see Fig. 2-24).

triceps in the lower third of the arm and may be damaged if that muscle

is elevated off the humerus in anything but an epi-periosteal plane

(see Fig 2-42).

bone cannot be exposed effectively above the spiral groove using the

posterior approach. At this point, the deltoid muscle (which is the

outer layer of the musculature) also crosses the operative field. More

proximal exposures should be accomplished by the anterior route.

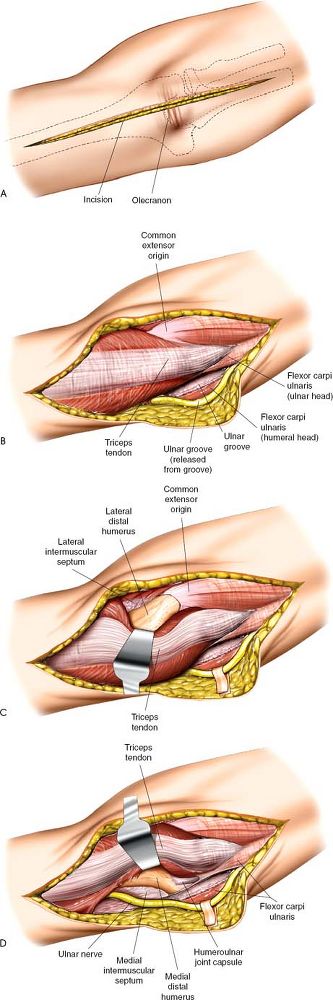

incision can be extended distally over the olecranon; deepening the

approach provides access to the elbow joint via an olecranon osteotomy

(see Posterior Approach in Chapter 3; Figs. 2-26 and 2-27).

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the lateral condyle

-

Surgical treatment of tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) 4

lateral portion of the elbow joint except by ex-tension. The joint

itself should be accessed by the posterior, posterolateral, or

anterolateral approach.

the arm lying across the chest. Exsanguinate the arm either by

elevating it for 3 minutes or by applying a

soft, thin rubber bandage or exsanguinator. Then, apply a tourniquet (Fig. 2-28).

|

|

Figure 2-26

The incision can be extended distally over the olecranon to give access to the elbow joint via an olecranon osteotomy. Proximal extension cannot be used effectively above the spiral groove because of the position of the radial nerve. |

|

|

Figure 2-27 (A) To extend the approach distally, extend the skin incision over the olecranon and subcutaneous border of the ulna. (B) Deepen the incision to expose the triceps tendon. Identify and dissect out the ulnar nerve. (C)

Develop a plane on the lateral aspect of the triceps muscle belly and tendon. Retract the muscle medially to expose the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus. (D) Develop a plane on the medial aspect of the triceps muscle belly and tendon. Retract the muscle laterally to expose the medial supracondylar ridge of the humerus. |

|

|

Figure 2-28

Position of the patient on the operating table. Place the patient supine on the operating table with the arm lying across the chest. |

|

|

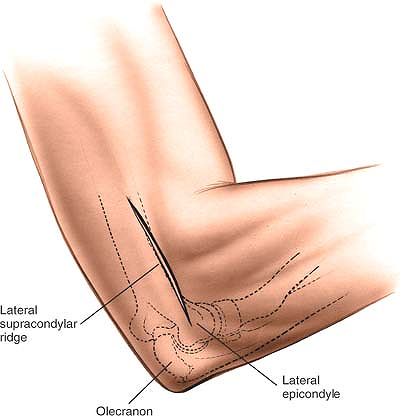

Figure 2-29 Make a straight or curved incision over the lateral supracondylar ridge of the elbow.

|

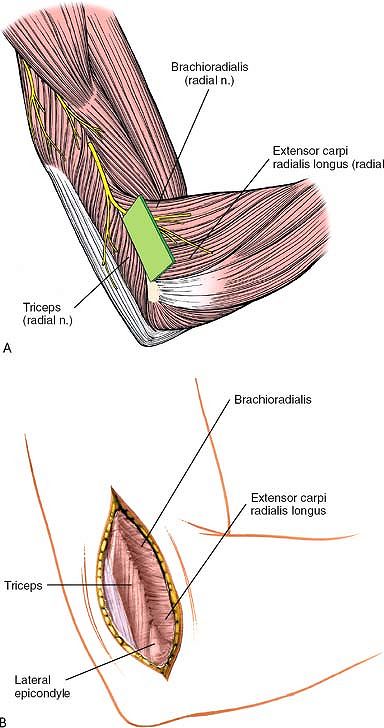

triceps and the brachioradialis muscles are supplied by the radial

nerve. Because the nerve supplies these muscles well proximal to the

area of the surgical approach, however, the plane between them can be

exploited distally without fear of damaging the nerve supply to either

muscle (Fig. 2-30A).

|

|

Figure 2-30 (A, B)

Intermuscular plane between the triceps and brachioradialis muscles. Both are supplied by the radial nerve proximal to the incision. |

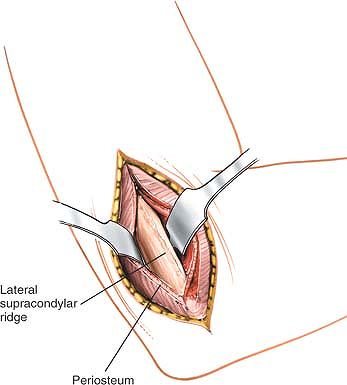

Define the plane between the brachioradialis, which originates from the

lateral supracondylar ridge, and the triceps, and cut between these

muscles down to bone, reflecting the brachioradialis anteriorly and the

triceps posteriorly (Fig. 2-31; see Fig. 2-44).

If further exposure of the bone is required, reflect the triceps off

the back of the humerus. Release the extensor origin if a better view

of the lateral epicondyle is needed (Fig. 2-32).

septum in the distal third of the arm. It is safe as long as the

approach is not extended proximally (see Fig. 2-46).

|

|

Figure 2-31

Incise the deep fascia in line with the skin incision. Define the plane between the brachioradialis and the triceps muscle and make an incision between them down onto the lateral supracondylar ridge. Reflect the brachioradialis anteriorly and the triceps posteriorly. |

lateral approach can be extended to the radial head only by using the

intramuscular plane between the anconeus muscle (which is supplied by

the radial nerve) and the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle (which is

supplied by the posterior interosseous nerve; see Posterior Approach to the Radius in Chapter 4 and see Fig. 2-32).

This approach cannot be extended further distally due to the presence

of the posterior interosseous nerve winding round the neck of the

proximal radius.

|

|

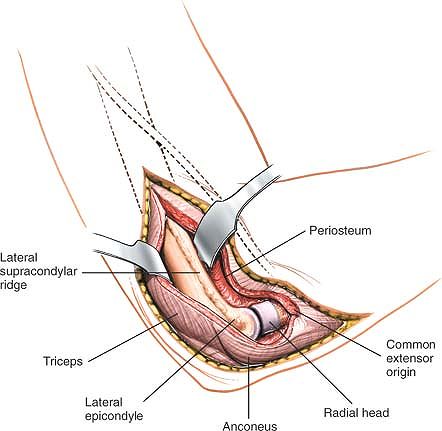

Figure 2-32

The incision may be extended to expose the radial head by using the internervous plane between the anconeus (radial nerve) and the extensor carpi ulnaris (posterior interosseous nerve). The common extensor origin is detached and reflected anteriorly. The triceps also may be reflected more posteriorly. Proximal extension is not possible because of the course of the radial nerve. |

arm do not stay neatly in one operative field, but cross from

compartment to compartment as they course down the arm. Therefore, it

is easiest to view the anatomy of the arm as consisting of two major

muscle compartments, flexor and extensor, that share responsibility for

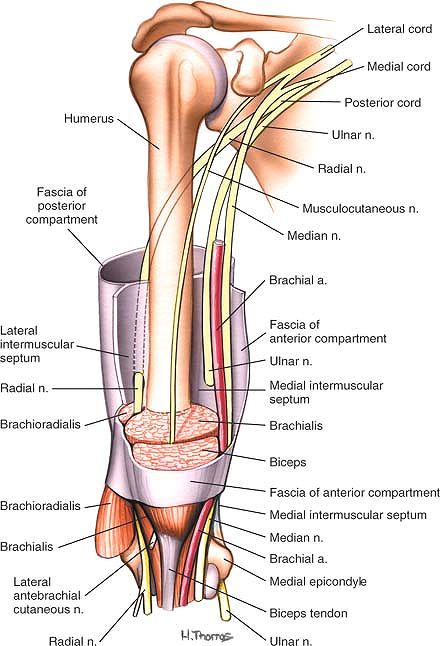

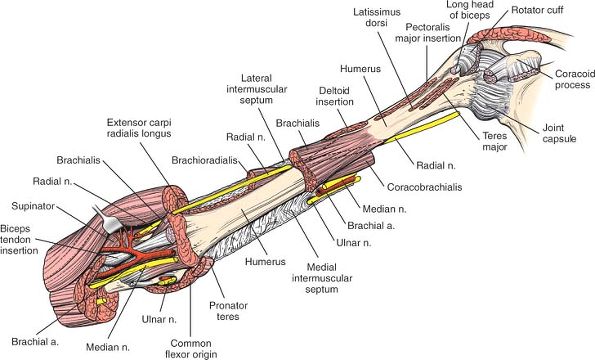

three major nerves and arteries (Fig. 2-33).

-

The anterior flexor compartment

contains three muscles: the coracobrachialis, the biceps brachii, and

the brachialis. Two are flexors of the elbow; all are supplied by the

musculocutaneous nerve. -

The posterior extensor compartment

consists of one muscle, the triceps brachii, which is supplied by the

radial nerve. In the distal two thirds of the arm, the muscle

compartments are separated by lateral and medial intermuscular septa.

|

|

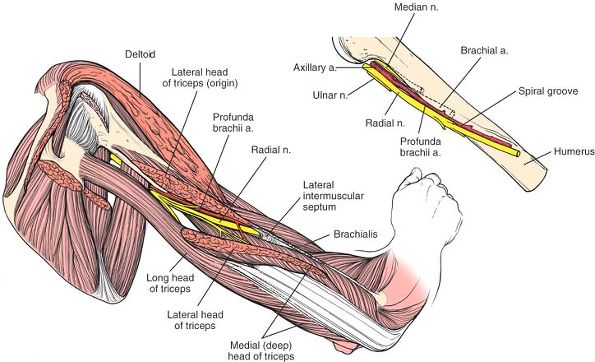

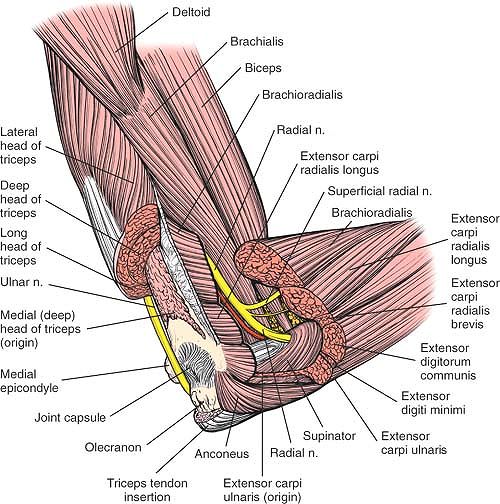

Figure 2-33

The compartments of the arm are shown. The muscles are removed partially to show the course of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves as they run down the arm. The relationships of the nerves to the compartments and septa are seen. |

-

The radial nerve,

which is the key surgical landmark in the arm, is the continuation of

the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It begins behind the

axillary artery at the shoulder, runs along the posterior wall of the

axilla (on the subscapularis, latissimus dorsi, and teres major

muscles), and then passes through

P.99

the

triangular space between the long head of the triceps muscle and the

shaft of the humerus beneath the teres major muscle. In the arm, the

nerve lies in the spiral groove on the posterior aspect of the humerus

between the lateral and medial (deep) heads of the triceps muscle.

After crossing the back of the humerus and giving off branches to the

lateral head and the lateral part of the medial head of the triceps,

the radial nerve pierces the lateral intermuscular septum, entering the

anterior compartment. At this point, the nerve may be vulnerable to

distal locking bolts inserted from the lateral side of the arm. The

nerve lies between the brachioradialis and brachialis muscles as it

crosses the elbow joint. There, it supplies the brachioradialis,

extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, and

anconeus muscles (see Figs. 2-29, 2-33, 2-37, 2-42, 2-45, and 2-46).

Although a radial nerve palsy is not uncommon following fractures of

the humeral shaft, the vast majority of these are due to a neurapraxia.

Exploration of the nerve is, therefore, not mandatory if a nerve palsy

is present following fracture. The presence of a nerve palsy following

reduction in a patient without an initial neurological lesion is a good

indication for exploration as the nerve may have become trapped between

the bony fragments during reduction.![]() Figure 2-34

Figure 2-34

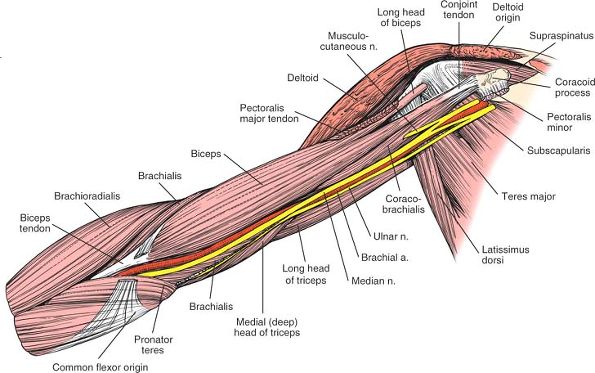

Superficial layer of muscles of the arm. Note the course of the

brachial artery and the median and ulnar nerves. The brachial artery

starts medial to the median nerve. In the distal part of the arm, it

moves lateral to the median nerve before entering the cubital fossa. -

The median nerve

remains in the anterior compartment, anteromedial to the humerus. It

runs with the brachial artery, lateral to it in the upper arm and

medial to it in the cubital fossa. -

The ulnar nerve

lies behind the brachial artery in the anterior compartment of the

upper half of the arm. It pierces the medial intermuscular septum about

two thirds of the way down the arm to enter the posterior compartment,

where it lies with the triceps muscle. It then travels on the back of

the medial epicondyle of the humerus, where it is almost subcutaneous

in location. Similar to the median nerve, it has no branches in the arm

(see Figs. 2-37, 2-43, and 2-45).

-

The brachial artery runs with the median

nerve down the medial border of the arm under the biceps brachii muscle

and onto the brachialis muscle. The artery can be palpated along its

entire length, because the deep fascia of the arm is the only medial

covering. The artery lies medial to the humerus in the upper two thirds

of the arm. At the elbow, it curves laterally to lie over the anterior

surface of the bone, where it may be damaged in supracondylar fractures

of the humerus (Figs. 2-34 and 2-35).P.100 Figure 2-35

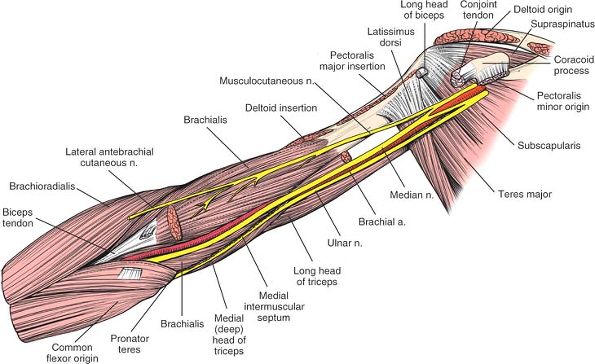

Figure 2-35

The anterior fibers of the deltoid have been removed. The pectoralis

major and minor have been resected at their insertions. Note the

relationship of the nerves to the teres major, subscapularis, and

latissimus dorsi, as well as the point where the musculocutaneous nerve

enters the coracobrachialis muscle. Distally, note the position of the

brachial artery and median nerve at the tendinous insertion of the

biceps. -

The profunda brachii artery runs with the radial nerve, supplying the triceps brachii muscle (see Figs. 2-41 and 2-42).

-

The ulnar collateral artery runs with the ulnar nerve. The three arteries anastomose freely with one another around the elbow joint.

arm closely parallels the lines of cleavage of the skin. More

proximally, however, the same incision crosses perpendicular to the

lines of cleavage. The cosmetic appearance of anterior scars,

therefore, is variable and dependent on their location.

humerus crosses the lines of cleavage of the skin at almost 90°. Scars

made by posterior incisions are likely to be broad.

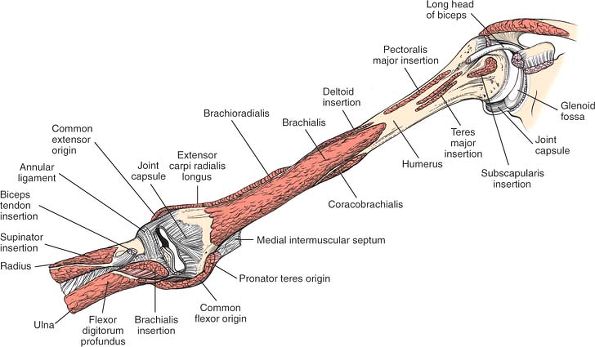

deltoid muscle (which is supplied by the axillary nerve) and the

pectoralis major muscle (which is supplied by the lateral and medial

pectoral nerves; see Anterior Approach in Chapter 1). Distally, the approach involves the muscles of the flexor compartment of the arm (Figs. 2-36, 2-37 and 2-38; see Figs. 2-34 and 2-35).

elbow flexor, the workhorse of the upper arm. The biceps only really

comes into play when extra strength or speed of flexion is required.

|

|

Figure 2-36

The biceps muscle has been removed at its proximal origins—its conjoined tendon and long head. A portion of the coracobrachialis has been removed to reveal the musculocutaneous nerve running on the brachialis muscle, supplying it. The median nerve and ulnar nerve course through the arm without supplying its muscles. |

|

|

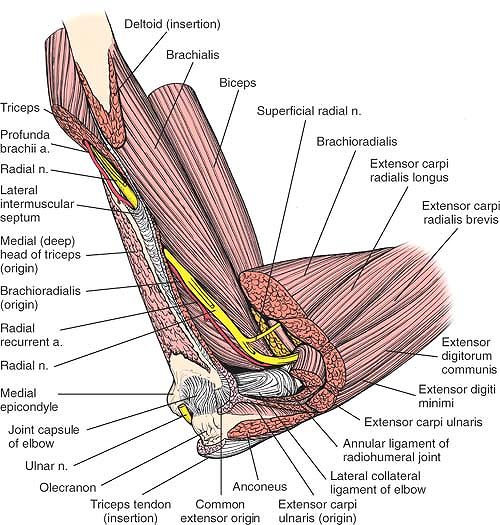

Figure 2-37

The central portion of the brachialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus have been resected to reveal the distal humerus and the course of the radial nerve as it pierces the lateral intermuscular septum to enter the anterior compartment. The radial nerve continues distally into the elbow before entering the supinator muscle. Medially, the relationships of the median nerve, brachial artery, and ulnar nerve are revealed. The median nerve is anterior to the brachial artery. The ulnar nerve, situated posteriorly, penetrates the medial intermuscular septum to enter the posterior compartment of the arm. The partially resected flexor-pronator group reveals the deeper structures at the level of the elbow. |

|

|

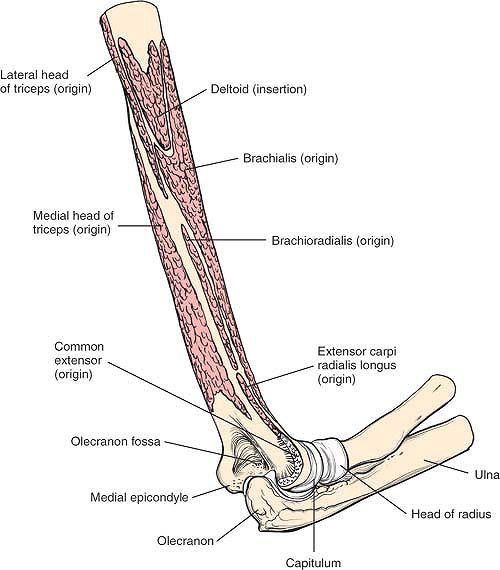

Figure 2-38 The origins and insertions of the muscles of the arm.

Brachialis. Origin. Lower two thirds of anterior surface of humerus. Insertion. Coronoid process and tuberosity of ulna. Action. Flexor of forearm. Nerve supply. Musculocutaneous and radial nerves.

|

nerve supply. The lateral part of the muscle is supplied by the radial

nerve, and the medial part is supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve.

Thus, the muscle can be split longitudinally without either side being

denervated. Because the musculocutaneous nerve is the major nerve

supply to the brachialis, even cutting the radial nerve supply to the

muscle seems to have little clinical effect. That is why the plane

between the brachialis and the adjacent lateral muscle, the

brachioradialis, is useful in surgery.

nerve supply high up in the axilla, close to its origin; the lateral

head receives its supply lower, at the upper level of the spiral

groove. The two heads can be split up to the level of the spiral groove

without compromising the nerve supply of either (see Fig. 2-47; see Figs. 2-39, 2-40, 2-41, 2-42 and 2-43).

medial half receives fibers from the radial nerve. The fibers run

alongside the ulnar nerve, so closely bound to it that they once were

thought of as branches of the ulnar nerve. They actually are radial

fibers that are “hitchhiking” in the ulnar nerve substance.5

supply from the main trunk of the radial nerve as it crosses the back

of the humerus in the spiral groove. Because of its dual nerve supply,

the medial head may be split longitudinally to expose the posterior

surface of the humerus.

This ligament connects a supracondylar spur of bone to the medial

epicondyle of the humerus. It may trap the median nerve between itself

and the underlying bone. Entrapment produces symptoms similar to those

of carpal tunnel syndrome.7

Compression of the median nerve at this level can be differentiated

from compression within the carpal tunnel because the flexor muscles of

the forearm, as well as the palmar cutaneous branches of the median

nerve, are affected. All these branches come off below the ligament and

above the carpal tunnel.

|

|

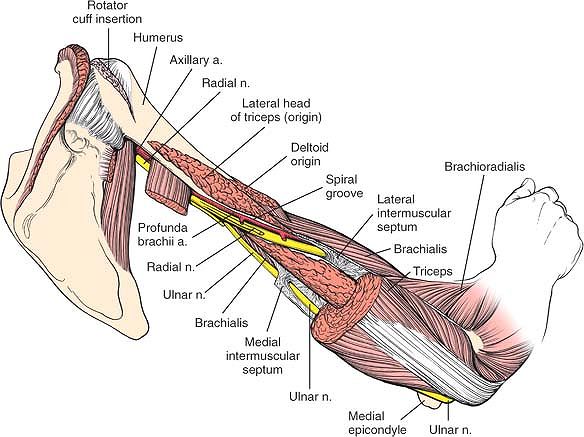

Figure 2-39 The anatomy of the posterior aspect of the arm. Note the cleavage plane between the long and lateral heads of the triceps.

|

|

|

Figure 2-40 The most posterior portion of the deltoid muscle has been removed to reveal the origin of the lateral head of the triceps.

Triceps Brachii. Origin.

Long head from infraglenoid tuberosity of scapula. Lateral head from posterior and lateral aspect of humerus. Medial (deep) head from lower posterior surface of humerus. Insertion. Upper posterior surface of olecranon. Action. Extensor of forearm. Weak adductor of shoulder. Nerve supply. Radial nerve. |

|

|

Figure 2-41

The central portion of the lateral head of the triceps has been removed to reveal the courses of the radial nerve and profunda brachii artery in the spiral groove. The fibers of the medial head of the triceps surround the radial nerve in its groove, protecting it from the bone. Detail of the relationship among the radial nerve, the axillary artery, and the profunda brachii artery (inset). The axillary artery becomes the brachial artery on the anterior surface of the humerus. There it gives off a branch, the profunda brachii artery, which continues posteriorly with the radial nerve through the triangular space and the spiral groove. |

|

|

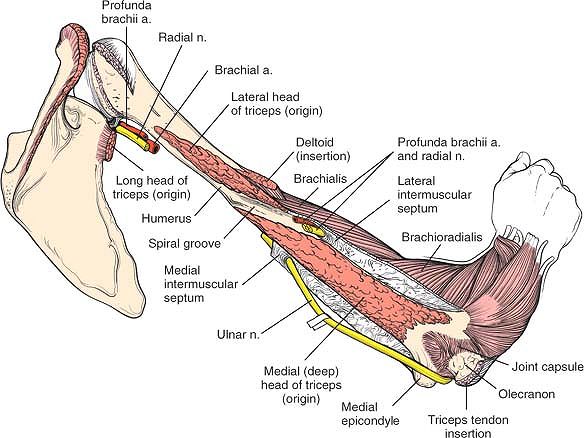

Figure 2-42

Resection of the proximal half of the triceps. The radial nerve and profunda brachii artery run in the spiral groove between the origins of the lateral and deep heads of the triceps. The nerve and vessel penetrate the lateral intermuscular septum before entering the anterior compartment of the arm. The ulnar nerve pierces the lateral intermuscular septum to gain entrance to the posterior compartment of the arm. |

|

|

Figure 2-43

The entire triceps muscle has been removed, uncovering the entire posterior surface of the humerus. The medial and lateral intermuscular septa and the nerves that penetrate them are seen. |

used for the insertion of intramedullary nails for the treatment of the

following:

-

Acute humeral shaft fractures

-

Pathological humeral shaft fractures

-

Delayed union and nonunion of humeral shaft fractures

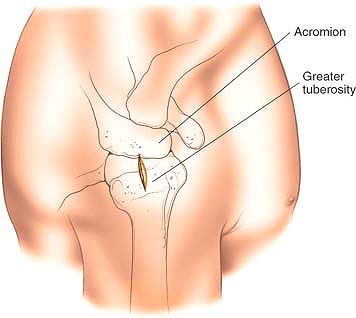

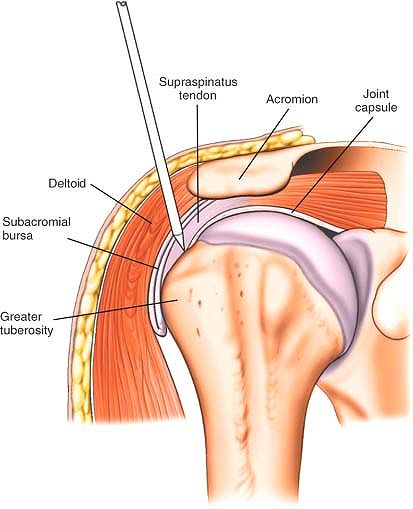

the upper end of the humerus is covered entirely with articular

cartilage mean that all nails are angled at their upper end and are

inserted via the lateral cortex of the humerus. The entry point for an

intermedullary nail into the humerus is determined radiographically,

with a template of the required nail superimposed over a radiograph of

the injured humerus. The entry point depends on the specific design of

the nail. The most usual entry point is just lateral to the articular

surface of the humeral head and just medial to the greater tuberosity

(see Fig. 2-52).

Position the patient so that the shoulder lies over the edge of the

table. Alternatively, use a specialized table that allows radiographic

visualization of the shoulder in both anterior-posterior and lateral

planes. Ensure that the cervical spine is adequately supported and that

lateral flexion of the cervical spine is avoided to prevent a traction

lesion of the brachial plexus.

|

|

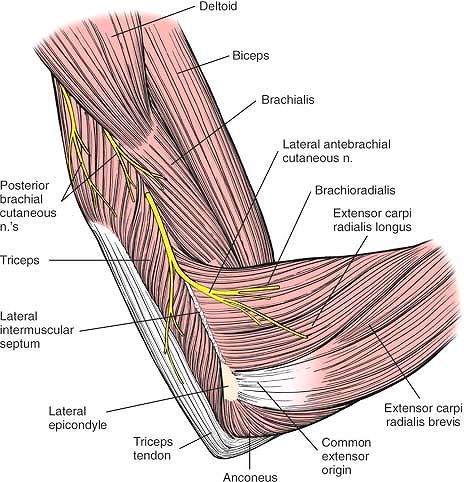

Figure 2-44 The lateral aspect of the humerus, with the overlying superficial cutaneous nerves.

|

|

|

Figure 2-45

The posterior aspect of the humerus and elbow joint and the course of the ulnar nerve. The lateral intermuscular septum runs beneath the brachioradialis. The main continuation of the radial nerve is the posterior interosseous nerve, which pierces the supinator muscle through the arcade of Frohse. |

|

|

Figure 2-46

The lateral intermuscular septum and the course of the radial nerve as it passes from the spiral groove through the intermuscular septum to emerge in the forearm from between the brachialis and the brachioradialis. The muscles covering the posterolateral aspect of the joint have been removed to reveal the joint capsule. |

|

|

Figure 2-47 The muscles have been removed completely, showing the origins of the musculature of the posterior humerus.

|

|

|

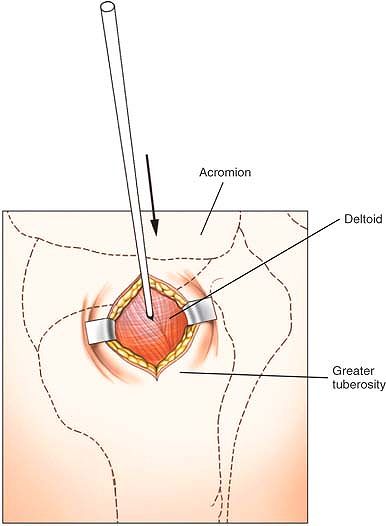

Figure 2-48 Palpate the lateral border of the acromion and then make a 2-cm incision from that border down the lateral aspect of the arm.

|

|

|

Figure 2-49 Insert a guidewire through the substance of the deltoid muscle under image intensifier control.

|

the skin incision, down through the substance of the deltoid muscle and

rotator cuff to the correct insertion point on the humerus (Fig. 2-49).

This position has been determined on the preoperative x-ray plan.

Confirm that the wire is in the correct position by the use of a C-arm

image intensifier in both anterior-posterior and lateral planes.

|

|

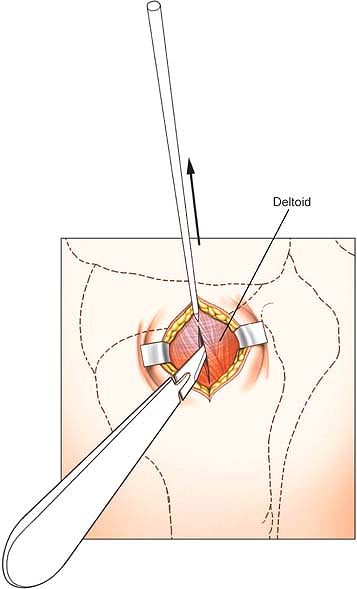

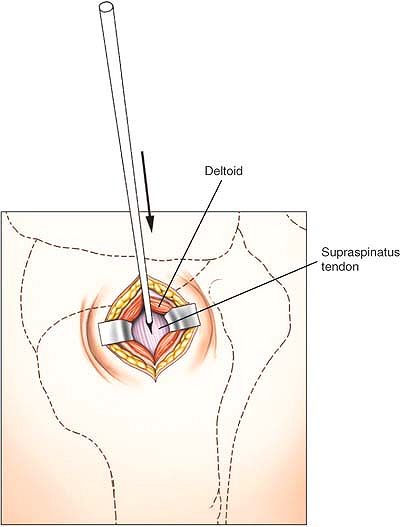

Figure 2-50

Enlarge the track made by the wire using a point-ended scalpel. You will incise part of the deltoid and part of the supraspinatus tendon. |

|

|

Figure 2-51 Insert the wire into the proximal end of the humerus under image intensifier control.

|

blade, following the track of the wire using a C-arm image intensifier

to confirm position (Fig. 2-50). Incise a small

portion of the deltoid and make a small clean-edged incision through

part of the supraspinatus tendon. Withdraw the blade and reinsert the

wire. Enter the proximal end of the humerus using an awl or drill,

depending on the nail to be used (Figs. 2-51 and 2-52).

proximal humerus. They are also at risk during insertion of proximal

locking bolts. This incision should, therefore, not risk damage to the

axillary nerve (see Fig. 1-39). The nerve may, however, be damaged by proximal interlocking bolts inserted from lateral to medial (see Fig 2-52).

will be incised by this approach. A degree of damage to the rotator

cuff is therefore inevitable in proximal humeral nailing using

conventional nails (see Fig. 1-7). Damage to

the rotator cuff is minimized by ensuring that any drills used are

passed through protection sleeves, but a significant degree of

stiffness of the shoulder occurs postoperatively in large numbers of

patients following antegrade humeral nailing.

extension may be needed if closed reduction of proximal humeral fractures cannot be obtained (see Fig. 1-39).

|

|

Figure 2-52

Lateral view of the shoulder, revealing insertion of the guidewire. The most common entry point is just lateral to the articular surface of the humeral head and just medial to the greater tuberosity. |

MD, Wilson TL, Winston K et al: Functional outcome following surgical

treatment of intra-articular distal humeral fractures through a

posterior approach. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 82:1701, 2000