Radial Head

-

The capitellum and the radial head are reciprocally curved.

-

Force transmission across the

radiocapitellar articulation takes place at all angles of elbow flexion

and is greatest in full extension. -

Full rotation of the head of the radius requires accurate anatomic positioning in the lesser sigmoid notch.

-

The radial head plays a role in valgus stability of the elbow, but the degree of conferred stability remains disputed.

-

The radial head is a secondary restraint

to valgus forces and seems to function by shifting the center of

varus-valgus rotation laterally, so the moment arm and forces on the

medial ligaments are smaller. -

Clinically, the radial head is most

important when there is injury to both the ligamentous and

muscle-tendon units about the elbow. -

The radial head acts in concert with the interosseous ligament of the forearm to provide longitudinal stability.

-

Proximal migration of the radius can occur after radial head excision if the interosseous ligament is disrupted.

-

Most of these injuries are the result of

a fall onto the outstretched hand, the higher-energy injuries

representing falls from a height or during sports. -

The radial head fractures when it

collides with the capitellum. This can occur with a pure axial load,

with a posterolateral rotatory force, or as the radial head dislocates

posteriorly as part of a posterior Monteggia fracture or posterior

olecranon fracture-dislocation. -

It is frequently associated with injury to the ligamentous structures of the elbow.

-

It is less commonly associated with fracture of the capitellum.

-

Patients typically present with limited elbow and forearm motion and pain on passive rotation of the forearm.

-

Well-localized tenderness overlying the radial head may be present, as well as an elbow effusion.

-

The ipsilateral distal forearm and wrist

should be examined. Tenderness to palpation or stress may indicate the

presence of an Essex-Lopresti lesion (radial head fracture-dislocation

with associated interosseous ligament and distal radioulnar joint

disruption). -

Medial collateral ligament competence

should be tested, especially with type IV radial head fractures in

which valgus instability may result. -

Aspiration of the hemarthrosis through a

direct lateral approach with injection of lidocaine will decrease acute

pain and allow evaluation of passive range of motion. This can help

identify a mechanical block to motion.

-

Standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral

radiographs of the elbow should be obtained, with oblique views

(Greenspan view) for further fracture definition or in cases in which

fracture is suspected but not apparent on AP and lateral views. -

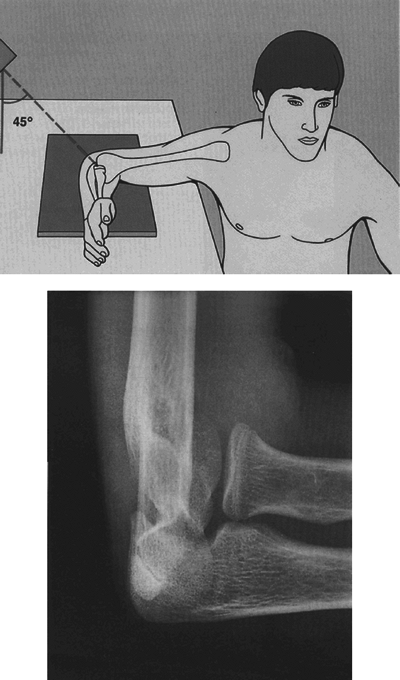

A Greenspan view is taken with the

forearm in neutral rotation and the radiographic beam angled 45 degrees

cephalad; this view provides visualization of the radiocapitellar

articulation (Fig. 20.1). -

Nondisplaced fractures may not be readily

appreciable, but they may be suggested by a positive fat pad sign

(posterior more sensitive than anterior) on the lateral radiograph,

especially if clinically suspected. -

Complaints of forearm or wrist pain should be assessed with radiographic evaluation.

-

Computed tomography may be utilized for

further fracture definition for preoperative planning, especially in

cases of comminution or fragment displacement.

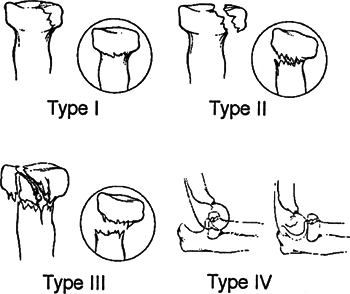

| Type I: | Nondisplaced fractures |

| Type II: | Marginal fractures with displacement (impaction, depression, angulation) |

| Type III: | Comminuted fractures involving the entire head |

| Type IV: | Associated with dislocation of the elbow (Johnston) |

-

Correction of any block to forearm rotation

-

Early range of elbow and forearm motion

-

Stability of the forearm and elbow

-

Limitation of the potential for ulnohumeral and radiocapitellar arthrosis, although the latter seems uncommon

-

Most isolated fractures of the radial head can be treated nonoperatively.

-

Symptomatic management consists of a sling and early range of motion 24 to 48 hours after injury as pain subsides.

-

Aspiration of the radiocapitellar joint

with or without injection of local anesthesia has been advocated by

some authors for pain relief. Figure 20.1. Schematic and radiograph demonstrating the radial head-capitellum view (Reproduced with permissionfrom Greenspan A. Orthopedic Imaging. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2004.)

Figure 20.1. Schematic and radiograph demonstrating the radial head-capitellum view (Reproduced with permissionfrom Greenspan A. Orthopedic Imaging. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins, 2004.) -

Persistent pain, contracture, and

inflammation may represent capitellar fracture (possibly osteochondral)

that was not appreciated on radiographs and can be assessed by magnetic

resonance imaging.

|

|

Figure 20.2. Mason classification of radial head and neck fractures.

(From Broberg MA, Morrey BF. Results of treatment of fracture- dislocations to the elbow. Clin Orthop 1987;216:109.)

|

-

The one accepted indication for operative

treatment of a displaced partial radial head fracture (Mason II) is a

block to motion. This can be assessed by lidocaine injection into the

elbow joint. -

A relative indication is displacement of a large fragment greater than 2 mm without a block to motion.

-

A Kocher exposure can be used to approach

the radial head; one should take care to protect the uninjured lateral

collateral ligament complex. -

The anterolateral aspect of the radial head is usually involved and is readily exposed through these intervals.

-

After the fragment has been reduced, it is stabilized using one or two small screws.

-

Partial head fragments that are part of a

complex injury are often displaced and unstable with little or no soft

tissue attachments. -

Open reduction and internal fixation is performed when stable, reliable fixation can be achieved.

-

For an unstable elbow or forearm injury,

it may be preferable to resect the remaining intact radial head and

replace it with a metal prosthesis.

-

When treating a fracture-dislocation of the forearm or elbow with an associated fracture involving the entire head of the

P.213

radius, open reduction and internal fixation should only be considered

a viable option if stable, reliable fixation can be achieved.

Otherwise, prosthetic replacement is indicated. -

The optimal fracture for open reduction

and internal fixation has three or fewer articular fragments without

impaction or deformity, each should be of sufficient size and bone

quality to accept screw fixation, and there should be little or no

metaphyseal bone loss. -

Once reconstructed with screws, the radial head is secured to the radial neck with a plate.

-

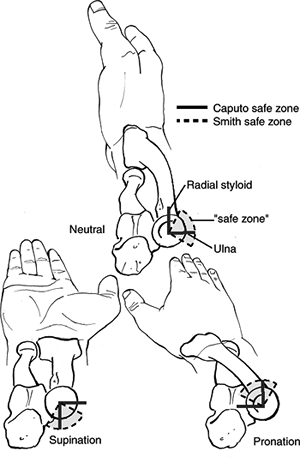

The plate should be placed posteriorly

with the forearm supinated; otherwise, it may impinge on the ulna and

restrict forearm rotation (Fig. 20.3).

-

The rationale for use is to prevent proximal migration of the radius.

-

Long-term studies of

fracture-dislocations and Essex-Lopresti lesions demonstrated poor

function with silicone implants. Metallic (titanium, vitallium) radial

head implants have been used with increasing frequency and are the

prosthetic implants of choice in the unstable elbow. -

The major problem with a metal radial head prosthesis is “overstuffing” the joint.

-

The level of excision should be just proximal to the annular ligament.

-

A direct lateral approach is preferred; the posterior interosseous nerve is at risk with this approach.

-

Patients generally have few complaints,

mild occasional pain, and nearly normal range of motion; the distal

radioulnar joint is rarely symptomatic, with proximal migration

averaging 2 mm (except with associated Essex-Lopresti lesion).

Symptomatic migration of the radius may necessitate radioulnar

synostosis. -

Late excision for Mason type II and III fractures produces good to excellent results in 80% of cases.

-

This is defined as longitudinal

disruption of forearm interosseous ligament, usually combined with

radial head fracture and/or dislocation plus distal radioulnar joint injury. -

It is difficult to diagnose; wrist pain is the most sensitive sign of distal radioulnar joint injury.

-

One should assess the distal radioulnar joint on the lateral x-ray view.

-

Treatment requires restoring stability of both elbow and distal radioulnar joint components of injury.

-

Radial head excision in this injury will result in proximal migration of the radius.

-

Treatment is repair or replacement of the radial head with evaluation of the distal radioulnar joint.

|

|

Figure

20.3. The nonarticular area of the radial head—or the so-called safe zone for the application of internal fixation devices—has been defined in various ways. Smith and Hotchkiss defined it based on lines bisecting the radial head made in full supination, full pronation, and neutral. Implants can be placed as far as halfway between the middle and posterior lines and a few millimeters beyond halfway between the middle and anterior lines. Caputo and colleagues recommended using the radial styloid and Lister tubercle as intraoperative guides to this safe zone, but this describes a slightly different zone. (From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

|

-

With stable fixation, it is essential to begin early active flexion-extension and pronation-supination exercises.

-

Contracture: This may occur secondary to prolonged immobilization or in cases with unremitting pain, swelling, and

P.215

inflammation, even after seemingly minimal trauma. These may represent

unrecognized capitellar osteochondral injuries. After a brief period of

immobilization, the patient should be encouraged to do

flexion-extension and supination-pronation exercises. The outcome may

be maximized by a formal, supervised therapy regimen. -

Chronic wrist pain may represent an

unrecognized interosseous ligament, distal radioulnar joint, or

triangular fibrocartilage complex injury. Recognition of such injuries

is important, especially in Mason type III or IV fractures in which

radial head excision is considered. Proximal migration of the radius

may require radioulnar synostosis to prevent progressive migration. -

Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: This may

occur especially in the presence of articular incongruity or with free

osteochondral fragments. -

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy: This may occur following surgical management of radial head fractures.

-

Missed fracture-dislocation: Unrecognized

(occult) fracture-dislocation of the elbow may result in a late

dislocation owing to a failure to address associated ligamentous

injuries of the elbow.