Polytrauma

injuries is often complex. Fractures that are complicated by truncal,

burn, or head injuries may be especially challenging. These children

may be in extremis or very unstable at the

time of presentation and thus may be poor candidates for anesthesia.

Nonorthopaedic injuries may take precedence and orthopaedic procedures

postponed. However, because of the unique problems that occur in these

patients both immediately after the injury and in the long term,

operative stabilization of fractures often can provide great benefits.

The sickest patients may benefit the most from surgery; however, unlike

adults, children do not derive any significant protection from

pulmonary complications as a result of long bone fracture stabilization.

of disability in children. Only acute infection causes more morbidity

than trauma. The estimated annual cost of pediatric injury is greater

than 7.5 billion dollars, with estimates of loss of future productivity

at greater than 8 billion dollars.

although the incidence of penetrating injury is rising. Motor vehicle

accidents, pedestrian injuries, recreational vehicle injuries, major

falls, and physical abuse are common causes.

swelling and fluid accumulation, including the cycle of hypoperfusion

and reperfusion, direct contusion, fluid and electrolyte imbalances,

and sepsis. Increased interstitial fluid makes access to and evaluation

of internal structures difficult. Surgery and wound closure are

difficult in swollen tissues. Organ function is diminished by fluid

accumulation and swelling, especially in the brain and lung. It often

takes several days to resorb excess interstitial fluid after resolution

of hemodynamic, metabolic, and septic derangements.

morbidity and mortality. This is worsened when there is polytrauma.

Increased intracranial pressure is always a source of concern and

usually requires intracranial pressure monitoring. Increased pressure

may prevent or delay surgical repair of other internal or skeletal

injuries. The brain injury itself may cause abnormal posturing,

increased muscle tone, or agitated movements—all of which can make

fracture management difficult. Injury-induced or medically induced coma

will render the child immobile and require constant vigilance for

contractures and bedsores. The search for additional injuries is more

difficult in the child who is unresponsive. Special care must be taken

to look for associated injuries which could otherwise be missed.

imbalances, and multiple transfusions may all have an effect on fluid

accumulation in the lung parenchyma that results in decreased

oxygenation of the blood. Intubation and sedation are usually required.

Hypoxemia will prevent prompt orthopaedic surgery. It may take several

days for pulmonary problems to resolve.

within the first several days of injury. Frequently the lungs are the

source of infection. Sepsis may contribute to multiple organ failure.

It may require the use of multiple antibiotics—some with side effects.

It complicates fluid and electrolyte management and provides an

undesirable setting for the placement of internal orthopaedic implants.

over that of orthopaedic injury. Unless simultaneous orthopaedic and

general surgery is possible (and it rarely is), the orthopaedic

procedures must follow treatment of the internal injuries.

transfusion of blood products, multiple injuries often do. Multiple

transfusions will often be associated with interstitial fluid

accumulation, impaired blood clotting, and decreased systemic immunity.

interrupted after severe trauma. Mobilized stores of nutrients will

sustain the child for a few days. After that, alimentation must be

provided either enterally or intravenously to provide substrates for

healing and repair.

care unit setting. Intensivists tend to make the important treatment

decisions and often the orthopaedist must receive permission before

initiating treatment for skeletal injuries. The orthopaedist is often

not familiar with intensive care techniques and procedures. Likewise,

intensivists and intensive care nurses are frequently unfamiliar with

orthopaedic devices and casts. Parents are often distraught or

restless. Patient and diligent communication must be maintained between

medical professionals and with parents.

Treatment decision must not be based on injury scale. Unless the child

is clearly going to die, orthopaedic treatment must proceed as if the

child is going to survive.

-

Deformity: splints and clothing must be removed to really see deformity.

-

Bleeding: watch for poke holes over fracture sites.

-

Swelling and ecchymosis: key to underlying injury but take some time to develop.

-

Tenderness: pain on palpation is always key. Even unconscious patient may manifest a useful response.

-

Abnormal motion: movement in the middle of a long bone or out of the plane of joint motion indicates radiography is necessary.

-

Crepitus: common after displaced fracture and reminds examiner that a splint will be necessary.

-

Pulses: important to document but not as important as perfusion status.

-

Neurologic function: important to note

before treatment is instituted. If a good neurologic examination isn’t

possible, write a note that explains why and remember to come back

later and keep trying.

|

TABLE 13-1 MODIFIED INJURY SEVERITY SCALE FOR CHILDREN WITH MULTIPLE INJURIES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Chest, cervical spine, and pelvis films should be ordered automatically.

-

Spine and extremity films should be requested based on clinical evaluation.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of spine or pelvis is indicated by suspicious radiographic or clinical evaluation.

-

In suspected abuse cases, a skeletal

survey is medicolegally indicated. Multiple fractures in various stages

of healing and metaphyseal corner fractures are highly suggestive of

abuse. Spiral fractures are not. -

Technetium bone scanning will be helpful

to locate skeletal injuries in victims who are very young or unable to

manifest a pain response because of central nervous system injury. -

Magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate joint derangement is not a priority in the acute injury phase.

-

The history is always important and leads the examiner to suspected areas of injury.

-

It is useful to know what the emergency transport team perceived to be injured at the scene.

-

Obviously life-threatening conditions take priority over orthopaedic injuries.

-

Splinted limbs should be rechecked with the splint removed if possible.

-

Obvious deformities should be noted. Open wounds must be noted.

-

Assume spinal injury until proved otherwise.

-

An inconsistent or changing history may suggest nonaccidental trauma. Be on the lookout.

-

Get plain radiographs of suspicious areas.

-

Ensure limb perfusion. If a problem, get help from the surgeons.

-

Provisional splintage decreases pain and limits further soft tissue injury.

-

Obtain special studies—CT scans, arteriograms, and so forth.

-

Think about and look for compartment syndrome, especially in patients unable to feel or speak.

-

Wash out open injuries as soon as it is safe for the patient.

-

Make plans to fix each fracture that would require surgery as if it were an isolated injury as soon as possible.

-

Consider stabilizing major bone fractures (i.e., femur, humerus, pelvis) to facilitate patient care.

-

Work hard to stabilize fractures within

limbs that will require frequent or painful manipulation, like those

with traumatic wounds, skin loss, burns, or compartment syndromes.

|

TABLE 13-2 GLASGOW COMA SCALE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Treatment of the uncomplicated femur fracture in young children often includes the use of traction or a spica cast.

-

□ Polytraumatized children often need to be turned, transported, and scanned—all of which are made difficult by traction.

-

□ Spica casts limit access to the limbs and abdomen.

-

-

Stabilization of long bone fractures enables transport and leaves the limbs and trunk free for examination or treatment.

-

Stabilization of long bone fractures

eliminates further damage to soft tissue by underlying mobile bone

segments and may limit further bleeding.P.174-

□ This is especially important in patients with head-injuries, who may be agitated or become spastic.

-

-

Patients with traumatic wounds, burns, or

compartment syndrome of limbs will likely need regular and repeated

access to the extremities.-

□ Circumferential casts make this difficult.

-

□ Without support, the fractured limb is painful and repeated manipulations for dressing changes would be cruel.

-

□ Stabilization of the skeleton makes wound management much easier.

-

-

Bony spinal injuries may render the spine unstable and render the neurologic structures at risk.

-

□ Surgical stabilization lessens pain with movement and protects the neural elements from unstable segments.

-

-

Simple closed fractures distal to the elbow or knee should be managed with reduction and splintage or casting.

-

Open fractures need surgical irrigation and drainage.

-

□ Stable fractures can be splinted or casted.

-

□ Unstable fractures or those that require frequent wound care will benefit from surgical stabilization.

-

-

Fractures of the femoral shaft should be

stabilized in multiply-injured children older than 6 years for the same

reasons as they are in children with fracture only. -

Surgical stabilization should be

considered for shaft fracture of the femur in polytraumatized children

of any age for the following reasons:-

□ Facilitate transport (i.e., in and out of scanners)

-

□ Facilitate hygiene

-

□ Facilitate wound, burn, or skin care

-

□ Facilitate rehabilitation

-

□ Obtain or maintain reasonable bony alignment which cannot be done by closed means

-

□ Control alignment and limit shortening

and further soft tissue injury in patients with head injuries who are

spastic or agitated -

□ Aid in pain control

-

-

Fractures of the pelvis should be

stabilized if there is gross displacement, gross instability, or

expanding hematoma that does not stabilize with transfusion. -

Fractures of humeral shaft do not

generally require surgical fixation, but in general the threshold for

surgical fixation can be lowered in the polytrauma setting. -

Reasons to consider surgical fixation include the following:

-

□ Inability to maintain alignment with usual splintage in a recumbent position

-

□ Difficulty with access to venous or arterial circulation due to splintage of upper arm

-

□ Multiple injuries in the same limb

-

□ Skin or wound problems of chest or upper arm

-

□ Agitation or spasticity in the patient with head injury

-

□ Proximate nerve or vascular injury

-

-

Periarticular fractures that would be managed by surgery in otherwise normal patients should be managed by surgery.

-

□ Postponing surgery because the child has a head injury or truncal injury often leads to problems or a compromised result.

-

□ The following scenario must be avoided:

The child is believed to be too sick to fix an orthopaedic injury and

is likely to die. The child recovers, and the untreated orthopaedic

injury becomes a major problem and a difficult reconstruction.

-

-

Fractures under burns can be safely fixed up to 48 hours after injury.

-

□ Incision through or around burned skin is relatively safe.

-

□ After that, the skin must be considered

to be colonized with bacteria and open reduction with internal fixation

will be prone to infection. -

□ Minimal or external fixation should be considered.

-

□ Otherwise, fixation should be delayed until skin healing or grafting.

-

|

|

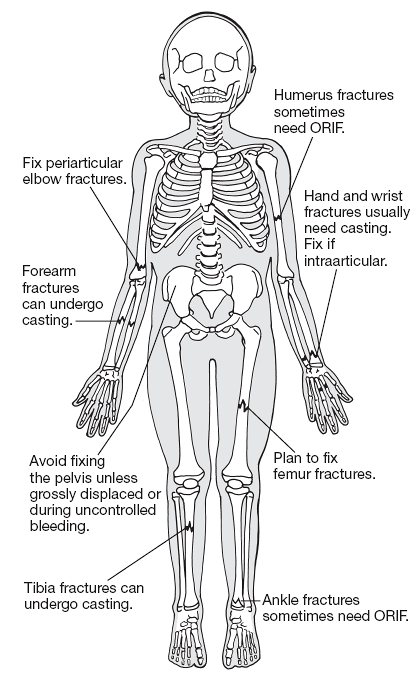

Figure 13-1

Periarticular fractures should be fixed just as indicated in isolated injuries. Fractures distal to knee and elbow can generally be managed in a cast. The threshold should be lowered for fixing the pelvis, humerus, and femur in the polytrauma patient. ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation. |

-

Intramedullary fixation is ideal for closed fractures of long bones (see sections on individual bone injuries).

-

In patients unable to tolerate extreme

positioning or vigorous pushing and pulling, external fixation and

plating may be good solutions. -

External fixation is almost always the

quickest and easiest solution for long bone fracture but commits the

patient to daily pin care. -

Try to avoid operating on the pelvis.

-

□ Use an anterior external fixator if simple stabilization is needed.

-

□ Be prepared to place anterior plates and posterior sacroiliac screws for the unstable pelvis in older children.

-

-

Periarticular fixation should be performed as in patients with isolated injury.

-

Do not harm the patient. Unresponsive shock and severely elevated intracranial pressure are reasons to delay fracture treatment.

-

Try to minimize blood loss and operative time in the sick patient.

-

Try to achieve stability that obviates the need for cast or splintage, especially proximal to the elbow or knee.

-

Goals for stabilization:

-

□ Pain control

-

□ Patient portability

-

□ Free access to trunk and circulation

-

□ Fracture alignment

-

□ Easy access to skin, burns, and traumatic wounds

-

-

Infection is always a possibility in the trauma patient.

-

The possibility of infection should not be a deterrent to skeletal stabilization, but active systemic sepsis should be.

-

Treat wound infection in the trauma patient just as in any other patient.

-

Unlike patients with isolated injuries, polytrauma patients are often manipulated by others who cannot feel the pain.

-

Skeletal fixation should be strong enough to protect against the manipulations of caretakers.

-

Head-injured or previously spastic patients may thrash about or have intense muscle spasms that can overcome weak fixation.

-

Be prepared to use strong fixation devices in these patients.

-

Prevention is easier than treatment.

-

Equinus contracture is ubiquitous in bedridden patients.

-

Ankle-foot orthoses and daily manipulation are helpful.

-

Flexion contractures of elbows, knees, and hips are not uncommon.

-

Daily physical therapy and varied positioning are helpful.

-

Warn the parents about the possibility of missed injury in the obtunded patient.

-

Check the patient at each visitation by palpating and tying to elicit tenderness.

-

Have a low threshold for obtaining radiographs.

-

Not uncommon in the polytrauma patient, especially if there is head injury.

-

Preventive treatment is not indicated.

-

Symptomatic residuals of heterotopic ossification can be treated after the patient is stabilized.

-

Positioning patients to maximize pulmonary care and social interaction is important.

-

Mobilization of joints through active

movement—in those who can—and passive movement—in those who cannot—is

important to maintain function. -

Children who will need their upper limbs

to provide mobility with either crutches or wheelchair after the acute

phase of trauma should begin working on strength as soon as possible in

the hospital. -

Weightbearing should be encouraged as soon as callus is seen unless there are other mitigating factors.

-

For larger children who are unable to transfer, consider the home use of a hospital bed, lift, and bedside commode.

-

Let the lawyer know that it may be years before the permanent residuals of injury can be fully realized in the growing child.

-

Survey and resurvey for injuries. Missed

injuries in the polytrauma setting are an embarrassment for the

physician and may be a cause for medicolegal action. Warn the parents

of the obtunded child that some injuries are hard to find and may not

be apparent at first. -

Fat embolism syndrome does occur in

children and adolescents. Watch for mental status changes with

tachycardia and decrease in arterial oxygenation after long bone

fracture. -

Rib fractures are a danger sign. They

generally occur in two clinical settings: high-energy trauma and abuse.

Look for associated injuries. -

Always assume the child is going to recover.

-

Try to operate before the child gets

sick. Problems with fluid retention, sepsis, respiratory failure, and

skin contamination with hospital flora are likely to worsen in the

first few days after injury. -

Warn parents that recovery may not be

full. Take the time to explain enough pathophysiology so that parents

do not confuse neurologic residuals with bad fracture treatment. -

Don’t lose track of the patient.

Polytrauma patients often are transferred to rehabilitation units after

the acute phase of treatment. It is important that they are followed

for their fractures by an orthopaedic surgeon.

AB, Hunt JL, Purdue GF, et al. Early orthopaedic intervention in burn

patients with major fractures. J Trauma 1991;31:888-893.

D, Starr AJ, Wilson P, et al. Early versus delayed stabilization of

pediatric femur fractures: analysis of 387 patients. J Orthop Trauma

1999;13:490-493.

SD, Gallagher D, Harris M, et al. Undiagnosed fractures in severely

injured children and young adults: identification with technetium

imaging. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1994;76:561-572.

RT, Gullahorn LJ, Yian EH, et al. Factors predictive of immobilization

complications in pediatric polytrauma. J Orthop Trauma 2001;15:338-341.

SA, Dominick T, Tyler-Kabara E, et al. Early versus late femoral

fracture stabilization in multiply injured pediatric patients with

closed head injury. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:594-599.

S, Milgrom C, Nyska M, et al. Femoral fracture treatment in

head-injured children: use of external fixation. J Trauma 1986;26:81-84.

VT. Orthopaedic treatment of fractures of the long bones and pelvis in

children who have multiple injuries. J Bone Joint Surg (Am)

2000;82:272-282.