Lumbar Disc Herniation

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Lumbar Disc Herniation

Lumbar Disc Herniation

Philip R. Neubauer MD

David B. Cohen MD

Description

-

Low back pain affects up to 85% of the population at some point in their lives (1).

-

Low back pain is one of the leading causes of disability in patients <50 years old.

-

Herniation of a lumbar disc:

-

1 of the major causes of acute and chronic lower back pain

-

May be associated with leg pain, weakness, and numbness, often referred to as “sciatica.”

-

-

Classification:

-

By location:

-

Posterolateral are the most common; the posterior longitudinal ligament is the weakest structure.

-

Usually affects the ipsilateral nerve root of the lower lumbar vertebrae.

-

Far lateral herniations may affect the ipsilateral nerve roots of the upper lumbar vertebrae.

-

Central herniations often are associated with back pain only, but they also may lead to cauda equina syndrome.

-

-

By morphology:

-

Protruded: Eccentric bulge of the nucleus pulposus with intact annulus fibrosis

-

Extruded: The nucleus protrudes through the annulus but remains intact.

-

Sequestered: Nucleus not intact, and a free fragment within the spinal canal

-

-

-

Synonyms: Herniated nucleus pulposus; Slipped disc; Ruptured disc; Sciatica

Epidemiology

-

Most commonly seen in patients 30–50 years old; rare before age 20 years (1).

-

Men are affected more often than women (2).

-

The lumbar spine is the spinal level most commonly affected by disc herniation (1).

-

The L4–L5 vertebral level is the most commonly affected level, followed by the L5–S1 vertebral level (1).

Risk Factors

-

Tobacco smoking

-

Jobs that require repetitive lifting

-

Obesity

Genetics

Controversy exists regarding a genetic link to lumbar disc herniation.

Pathophysiology

-

The intervertebral disc is made of an inner nucleus pulposus and an outer annulus fibrosis.

-

Formed primarily of type I and type II

collagen, the intervertebral disc’s main functions are to absorb axial

loads on the spinal column and to allow for fluid movements between

vertebrae. -

Vascular and neural elements are found exclusively within the peripheral fibers of the annulus fibrosus.

-

Nutrients flow to the intervertebral disc via diffusion from the hyaline cartilage endplates located above and below the disc (3).

-

Beginning in a person as young as 20 years old, the nucleus pulposus gradually looses water content.

-

With age, the intervertebral discs lose volume, shape, and viscoelastic ability.

Etiology

-

The cause of lumbar disc herniation appears to be related primarily to the normal degenerative process that occurs with aging.

-

It may be secondary to trauma.

-

Repetitive stresses on the lower back, as with heavy labor, may accelerate the process.

Signs and Symptoms

-

Pain is the usual presenting symptom.

-

May affect the back only, leg only, or both

-

Pain often is aggravated by forward flexion of the lumbar spine and relieved by extension.

-

-

Numbness in the dermatome associated with the affected nerve root may occur.

-

Weakness in the muscle associated with the affected nerve root may occur.

-

L3–L4 herniation causes an L4 root

compression characterized by anterior tibialis weakness, decreased

patellar reflex, and medial knee and leg sensory changes. -

L4–L5 herniation results in L5 symptoms,

including altered sensation over the lateral aspect of the calf and the

1st dorsal web space; extensor hallucis longus weakness may be evident. -

L5–S1 herniation compresses the S1 nerve

root, decreases ankle reflex, and causes decreased plantarflexion

strength and diminished sensation over the lateral aspect of the foot. -

Saddle anesthesia and changes in bowel or bladder habits may indicate cauda equina syndrome.

-

Cauda equina compression, which can result from a large herniated disc, should be decompressed on an emergency basis.

History

-

A thorough history should include the time course for the onset of pain.

-

Risk factors (e.g., occupation, tobacco history)

-

Changes in bowel or bladder function, specifically urinary retention, which may indicate cauda equina syndrome.

-

History of fall or trauma

-

History of constitutional symptoms (e.g., night sweats, fever, weight loss) should be included.

Physical Exam

-

A detailed neurologic evaluation is the most important aspect of examination.

-

Sensation in the lower extremity dermatomes and the strength of all major muscle groups should be documented.

-

All lower extremity reflexes should be tested.

-

Rectal examination:

-

Important for assessing sacral nerve

roots; assess rectal tone, perianal light touch and pinprick sensation,

and the anal wink reflex

-

-

A straight-leg-raise test:

-

Replication of symptoms is a result of stretched nerve roots (Fig. 1).

-

The pain is increased by ankle dorsiflexion.

-

A contralateral test with pain radiation below the knee is highly specific for lumbar disc herniation.

-

-

-

Gait disturbances or foot-drop may be a result of nerve compression and muscular weakness.

Tests

Imaging

-

AP and lateral radiographs for patients with symptoms lasting >6 weeks.

-

MRI:

-

Used to document the pathologic features if surgery is contemplated or spinal stenosis is suspected

-

Results may be misleading because false-positive findings are common.

-

Can be used to confirm the diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome

-

-

CT myelography may be used to diagnose lumbar disc herniation, but it is more invasive than, and has been replaced by, MRI.

-

Discography may help evaluate for

discogenic back pain and localize the site of pain generation to the

disc complex, but use and acceptance of this technique remains

controversial.

Pathological Findings

-

The nucleus pulposus is extruded through

defects in the annulus fibrosis, but it usually remains covered by the

thick posterior longitudinal ligament. -

Symptoms are secondary to tenting of nerve roots over the herniation.

-

The release of inflammatory mediators may exacerbate the mechanical pressure.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Lumbar spinal stenosis

-

Sciatic nerve entrapment below the spine

-

Spondylolysis

-

Muscular back pain

-

Degenerative disc disease

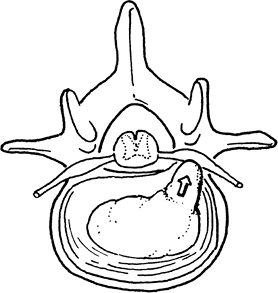

Fig. 1. In a herniated disc in the lumbar spine, material from the nucleus pulposus exerts pressure on the nerve root.

Fig. 1. In a herniated disc in the lumbar spine, material from the nucleus pulposus exerts pressure on the nerve root.

P.235

Initial Stabilization

Bed rest (not >2–3 days), then gradual increase in activity as cardiovascular status allows

General Measures

-

Initial treatment is nonoperative;

surgical intervention is reserved for patients for whom nonoperative

therapy fails or who present initially with severe symptoms. -

Care is directed toward symptomatic relief.

-

Early resumption of activity is important for recovery.

-

Prolonged bed rest should be avoided.

-

Activities that cause exacerbation of symptoms should be avoided.

-

-

NSAIDs or acetaminophen are recommended.

-

Diazepam or muscle relaxants have only a limited role for patients with lumbar disc herniations associated with muscle spasms.

-

Epidural steroids may be helpful for short- and long-term relief.

-

Manipulation, either manually or in traction, also may be beneficial on a short-term basis.

-

Narcotics should be reserved for the most severely symptomatic patients.

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Physical therapy in addition to NSAIDs for most patients with lumbar disc herniations

-

Proprioceptive techniques and abdominal and back-strengthening programs are essential.

-

The therapy program should include lower extremity stretching and strengthening.

Medication

First Line

-

Acetaminophen

-

NSAIDs

-

Narcotics in the early acute stage

Second Line

-

Oral corticosteroids

-

Epidural corticosteroid and anesthetic injections

Surgery

-

The decision to pursue surgery should be made on an individualized basis with patient input.

-

In general, surgical intervention is reserved for patients for whom aggressive nonoperative treatments have failed.

-

Operative therapy is more effective in treating symptoms related to the lower extremities than those related to back pain.

-

Postoperatively, patients may have recurrent or new onset back pain, with incidence rates up to 14% (4).

-

For patients with severe progressive

neurologic deficit, or the development of cauda equina syndrome,

surgery should be considered the 1st-line intervention. -

Surgical options include:

-

Open discectomy, laminectomy, or laminotomy

-

Microscopic discectomy

-

Endoscopic discectomy

-

-

Invasive nonsurgical options, such as chemonucleolysis, have fallen out of favor because of associated complications (5).

-

Patients treated nonoperatively should be seen every 6 weeks for 12–18 weeks and then on an as-needed basis.

-

After surgery:

-

Monitor patients for signs of nerve injury and postoperative wound infection.

-

Restrict activity for ~6 weeks to decrease the risk of recurrent disc herniation.

-

Request the patient to avoid lifting >10 pounds, bending, stooping, or twisting for 6 weeks after surgery.

-

Prognosis

-

Prognosis is excellent for complete recovery in most patients.

-

Intermittent back pain may persist in some patients.

Complications

-

Degenerative disc disease or persistent pain from other causes

-

Repeat herniation at the same or other levels

-

Disc infection or arachnoiditis after discectomy

Patient Monitoring

Monitoring of the healing progress is based clinically

on patient signs and symptoms, whether nonoperative or surgical

treatment was used.

on patient signs and symptoms, whether nonoperative or surgical

treatment was used.

References

1. Andersson GBJ. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet 1999;354:581–585.

2. Battie MC, Videman T, Parent E. Lumbar disc degeneration: epidemiology and genetic influences. Spine 2004;29:2679–2690.

3. Urban JPG, Holm S, Maroudas A, et al. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc: effect of fluid flow on solute transport. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;170: 296–302.

4. Carragee

EJ, Han MY, Suen PW, et al. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy

for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg 2003;85A:102–108.

EJ, Han MY, Suen PW, et al. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy

for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg 2003;85A:102–108.

5. Mathews HH, Long BH. Minimally invasive techniques for the treatment of intervertebral disk herniation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2002;10: 80–85.

Additional Reading

Biyani A, Andersson GBJ. Low back pain: pathophysiology and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:106–115.

Buttermann

GR. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: epidural steroid injection

compared with discectomy. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:670–679.

GR. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: epidural steroid injection

compared with discectomy. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg 2004;86A:670–679.

Codes

ICD9-CM

722.10 Herniated disc in lower spine

Patient Teaching

Patients should understand that most herniated discs improve with time and symptomatic treatment.

Activity

-

Patients should be encouraged to pursue activity as tolerated.

-

Long periods of bed rest may delay improvement of symptoms.

Prevention

Patients involved in heavy lifting may benefit from

instruction in proper lifting technique by a physical therapist or an

occupational medicine specialist.

instruction in proper lifting technique by a physical therapist or an

occupational medicine specialist.

FAQ

Q: Which provocative physical examination maneuvers can be used to help evaluate for a herniated lumbar disc?

A: Ipsilateral and contralateral straight-leg-raise tests.

Q: What are the signs of a herniated disc?

A:

Pain in both the back and the legs caused by pressure on the nerve from

the disc herniation. In severe cases, loss of bowel or bladder function

may occur, and these patients should be evaluated emergently.

Pain in both the back and the legs caused by pressure on the nerve from

the disc herniation. In severe cases, loss of bowel or bladder function

may occur, and these patients should be evaluated emergently.