HEMATOLOGY

that occurs primarily in males, resulting in clotting factors that are

nonfunctional or absent. Intraarticular hemorrhages in patients with

poorly controlled hemophilia can lead to progressive joint arthropathy.

The natural history of the disorder has changed significantly over the

past several decades, due to the development of factor replacement

therapy, but considerable orthopaedic morbidity still occurs.

-

The incidence of hemophilia is estimated to be 1 per 10,000 male births in the United States.

-

Approximately 95% of cases are caused by a variable lack of factors VIII or IX.

-

Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) is the most common (about 80% of cases).

-

□ Several different mutations cause the disorder, which accounts for the variable clinical severity.

-

□ It is an X-linked recessive disorder that affects males.

-

□ Hemophilia A is the result of a new mutation in approximately 33% of patients.

-

-

Hemophilia B (factor IX deficiency), also known as Christmas disease, is the next most common.

-

□ Clinically indistinguishable from hemophilia A.

-

□ Also transmitted as an X-linked disorder.

-

-

The third most common inherited

coagulation disorder is von Willebrand disease, caused by a variable

lack not only of factor VIII coagulant activity but also of factor

VIII-related activity responsible for adhesion of platelets to exposed

vascular subendothelium.-

□ This form is characterized by abnormal

bleeding from mucosal surfaces, therefore major hemophilic arthropathy

is relatively uncommon.

-

-

The exact pathophysiology of hemophilic arthropathy remains controversial.

-

Both the inflammatory cascade and iron deposition have been implicated in cartilage destruction.

-

The degree of hemarthropathy does not always directly correlate with the number of joint bleeds.

-

Hemarthrosis probably starts as a subsynovial, intramural hemorrhage that then ruptures into the joint cavity.

-

Spontaneous hemorrhages without antecedent trauma commonly occur in patients with a severe deficiency.

-

With repeated exposure to blood, the

synovium of joint hypertrophies and becomes hypervascular, leading to a

progressive cycle of synovitis and more bleeding. -

Histology of the hypertrophic synovium is

characterized by villous formation, markedly increased vascularity, and

chronic inflammatory cells. -

Hemosiderin deposits accumulate in the

lining cells of the synovial villi, and the inflammatory cells

congregate around the vessels and hemosiderin deposits. -

In summary, the result of repeated hemorrhage into a joint with chronic synovitis

-

Proteolytic enzymes released by the inflamed synovium attack both cartilage and bone.

-

As the hypertrophied synovium continues to expand, and the articular cartilage erodes, the joint space narrows.

-

Osteoporosis occurs from disuse, and the joint becomes immobile.

-

Grading of articular involvement can be seen in Table 26.1-1.

-

In children, chronic synovitis may also

cause asymmetric physeal growth, or early physeal closure, leading to

angular deformities or leg length discrepancies.

|

TABLE 26.1-1 GRADING OF SYNOVITIS AND ARTICULAR INVOLVEMENT IN HEMOPHILIC PATIENTS

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

-

A history of similarly affected males on the maternal side of the family, or typical behavior

-

A history of hemorrhage from major surface wounds and musculoskeletal sites.

-

Hemophiliacs rarely experience bleeding during the first years of life in the absence of trauma or surgery.

-

□ Hemarthroses usually begin after the child starts to walk.

-

-

The frequency and severity of bleeding

episodes commonly increase as the child attends school and becomes more

physically active and socially interactive. -

Patients with severe hemophilia typically develop their initial joint pathology between the ages of 5 to 15 years.

-

Abnormal bleeding may occur in any area of the body, but joints are the most frequent sites of repeated hemorrhage (Table 26.1-2).

-

The weightbearing joints are the most

common sites of hemophilic arthropathy, with the frequency of

involvement being, in decreasing order, the knee, elbow, shoulder,

ankle, wrist, and hip. The vertebral column is rarely involved. -

Clinical findings depend on the severity of hemorrhage and whether the hemarthrosis is acute, subacute, or chronic (Table 26.1-3).

-

Other musculoskeletal problems in hemophilia include:

-

□ Pseudotumor (slowly progressive

hemorrhage that increases in size within a confined space, causing

pressure necrosis and erosion of the surrounding tissues) -

□ Neuropraxias (femoral, peroneal, sciatic, median, and ulnar)

-

□ Ectopic ossifications

-

□ Fractures

-

□ Ischemic contractures or compartment syndrome

-

-

After history and physical examination, laboratory tests should be ordered (Table 26.1-4).

If these screening procedures suggest a bleeding tendency, factor

assays must be carried out to establish not only the specific

deficiency but also its degree. -

Most patients with hemophilia present to

an orthopaedist with a known diagnosis. Clinical manifestations of

hemophilia A and B are similar and depend on the blood levels of factor

VIII or IX (Table 26.1-5).

|

TABLE 26.1-2 DIFFERENTIATING BLEEDING FROM SYNOVITIS

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-

Distended capsule

-

Synovitis

-

Cartilage thinning

-

Widening and erosion of intercondylar notch

-

Enlargement of ossification centers (especially distal end of femur)

-

Widening of distal femoral epiphysis

-

Squaring of inferior pole of patella

-

Flattening of distal femoral condyles

-

Hemophiliac pseudotumor

-

Epiphyseal overgrowth with leg length discrepancy

-

Osteopenia

|

TABLE 26.1-3 CLINICAL STAGES OF HEMARTHROSIS

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

TABLE 26.1-4 ROUTINE LABORATORY TESTS FOR PATIENTS WITH COAGULOPATHY

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

TABLE 26.1-5 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEMOPHILIA ACCORDING TO BLOOD LEVELS OF FACTORS VIII AND IX

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

the orthopaedic advisory committee of the World Federation of

Hemophilia is shown Table 26.1-6. It includes functional status. An additional radiographic classification useful for bony changes is shown in Table 26.1-7.

has improved with the use of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI), which can provide early, detailed information about the

synovium, cartilage, and the joint spaces.

-

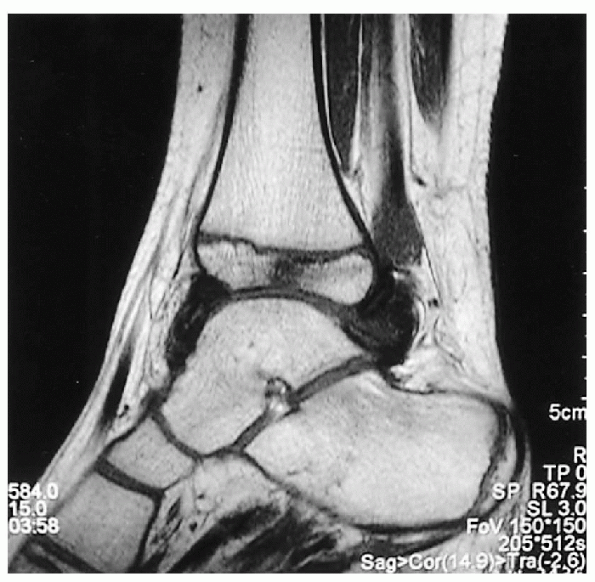

Hemosiderin deposits can be seen on MRI (Fig. 26.1-2), as can subchondral and intraosseous cysts or hemorrhage (Figs. 26.1-3 and 26.1-4).

-

□ The limitation of MRI is that the cost may be prohibitive when serial exams are necessary.

-

-

Ultrasound has been shown to be a sensitive and reproducible technique to assess synovial proliferation in a variety of joints.

-

The activity of disease, in terms of acute synovitis, may further be assessed with power Doppler ultrasound.

|

|

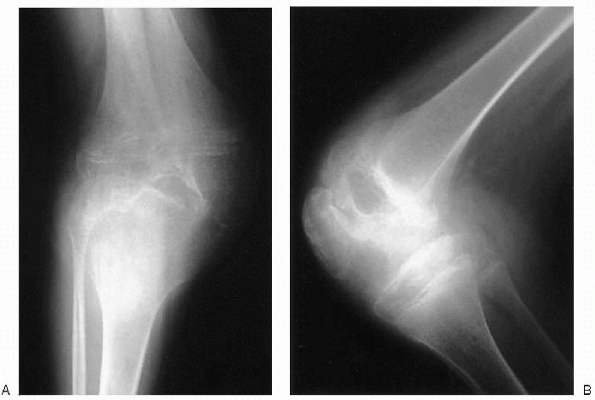

Figure 26.1-1 Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B)

knee plain radiographs of a 10-year-old boy with hemophilia: loss of joint cartilage space, marked enlargement of the epiphysis, and extensive joint destruction (stage V according to Arnold and Hilgartner radiographic classification). |

|

TABLE 26.1-6 ROENTGENOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION OF HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

TABLE 26.1-7 RADIOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION OF HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||

hematologist, with input from a variety of other medical professionals

including orthopaedists, physical therapists, vocational therapists,

nurses, dentists, social workers, psychiatrists, and genetic

counselors. There are several factors that affect the choice of type of

therapy (Table 26.1-8).

|

|

Figure 26.1-2

Right elbow magnetic resonance image of a 6-year-old boy with hemophilia. Synovial hypertrophy and large hemosiderin deposit are seen. |

America involves early intervention for bleeding episodes with

increased factor given at the onset of discomfort and, if possible,

even prior to the observation of joint swelling. This approach is often

referred to as an on-demand treatment. It involves the use of home

infusion of factor VIII without the need to be seen initially at a

hospital or a clinic. Factor levels of 30 to 50 IU/dL are optimal in

controlling an acute hemorrhage.

factor levels greater than 1%) prevents hemophilic arthropathy better

than on-demand therapy (Table 26.1-9).

It has been useful in preventing the spontaneous bleeding typically

seen in patients with severe disease. The amount of product necessary

to achieve a nonbleeding state with few breakthrough bleeding episodes

varies from patient to patient. The age of onset at which a patient may

begin to experience hemarthrosis also varies, but is usually before the

age of 4 years. Decreased hemophilic joint destruction and arthropathy

have been demonstrated in patients who have started prophylaxis at 2 to

3 years of age. In certain situations, factor VIII levels should be

increased for prophylaxis (Table 26.1-10).

|

|

Figure 26.1-3 Left ankle sagittal magnetic resonance image of a 6-year-old boy with hemophilia. Subchondral bone cyst is seen.

|

|

|

Figure 26.1-4 Eight-year-old boy with factor VIII deficiency. (A and B) Anteroposterior plain x-rays of the shoulder show cyst formation in the humeral head. (C and D) Coronal magnetic resonance images reveal marked synovial hyperplasia and hemosiderin deposits, called a blooming appearance.

|

|

TABLE 26.1-8 FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE CHOICE OF THERAPY FOR HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

TABLE 26.1-9 PROPHYLACTIC TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIC ARTHROPATHY

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(HIV) transmission and hepatitis in human factor VIII replacement,

recombinant products are preferred and are available for factors VII,

VIII, and IX. The dosage required to replace a factor deficiency

depends on the patient’s weight and plasma volume. The hematologist

makes the calculation and is in charge of administering the factor. The

orthopaedic surgeon, however, should be aware of the fact that 20 to 30

minutes after administration of the antihemophilic factor, the plasma

level will rise.

platelet aggregation and prolong the bleeding time, should be avoided

in patients with hemophilia. Patients should be warned against the use

of any medication containing an aspirin compound, guaiacolate, or

antihistamine. Proxyphene, paracetamol, meperidine, codeine

amitriptyline, or methadone may be used. Narcotic analgesics are used

with care because in such a chronic disease, addiction can easily

become a problem.

|

TABLE 26.1-10 SITUATIONS IN WHICH FACTOR VIII LEVELS SHOULD BE INCREASED

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

and yields the best results. Adequately prescribed and correctly

supervised physiotherapy very rarely requires concurrent replacement

therapy, except after surgery. Every patient generally requires

individual exercise programs.

cushioned lining. Care should be taken to avoid muscle atrophy. There

are four distinct functions for orthoses used in hemophiliac

arthropathy:

-

Protection and stabilization of an unstable joint

-

Nocturnal use, in the immediate postoperative period or to complete casting

-

Prevention of some joint contractures, in particular flexion deformity

-

Braces, splints, and walking bandaging are useful to enhance joint stability without limiting movement.

hemophilic arthropathy are generally divided into two groups:

procedures such as synovectomy that are done to control repetitive

joint bleeding episodes and the more conventional orthopaedic

procedures designed to correct or reconstruct joint deformities.

careful technique using tourniquet control when feasible and securely

ligating all vessels insofar as possible. Cautery is a less

satisfactory method of hemostasis in hemophiliacs. Before the wound is

closed, the tourniquet must be released and bleeding surgically

controlled. Appropriate perioperative factor replacement is imperative.

Some experts recommend aspiration only for an extremely tense

hemarthrosis and avoid aspiration in ordinary cases, citing the risk of

introducing infection, the discomfort to the patient, and the

possibility that aspiration will incite more bleeding of the joint.

Aspiration of the joint should be performed under strict aseptic

conditions.

-

Severe recurrent hemarthrosis (2 or 3 major bleeding episodes/mo)

-

Hemarthrosis that does not respond to aggressive medical management maintained for ≥6 mo

-

Failure to respond to orthopaedic nonsurgical treatment consisting of physical therapy and protection with crutches and orthoses

-

Radiographic stage II or III hemophilic arthropathy

of hemophilic arthropathy. The general consensus of opinion is that

synovectomy relieves pain, decreases swelling, and diminishes the

number of bleeding episodes per year (Box 26.1-1). Synovectomy is ineffective and contraindicated patients with radiographic stage IV or V hemophilic arthropathy.

loss of range of motion of the affected joint. Arthroscopic synovectomy

is most useful when performed before severe degenerative changes have

developed. Contraindication for arthroscopy of hemophilic patients is

inhibitory antibodies to factor replacement. As complete a synovectomy

as possible should be performed. After surgical synovectomy the knee

should be immobilized in a Jones bandage for 3 days and active movement

encouraged. Postoperative factor replacement supervised by a

hematologist is required. Weidel has shown with a 10- to 15-year

follow-up that the procedure was effective in stopping the bleeding

episodes, and by maintaining the range of motion, joint deterioration

continued to progress at a slower rate.

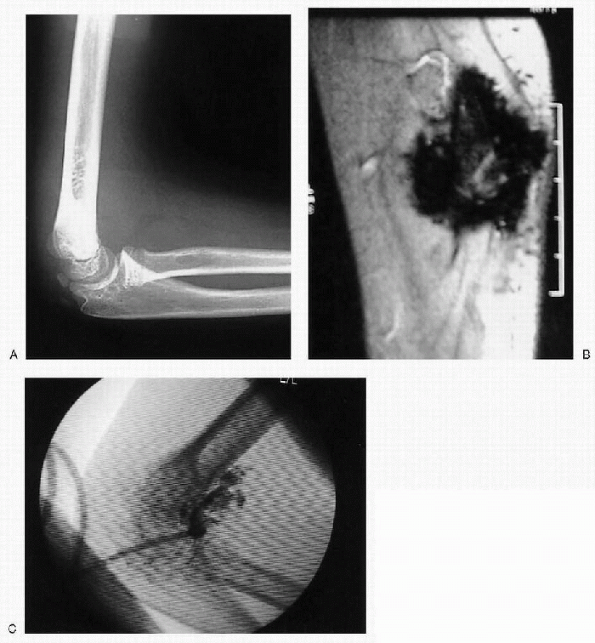

tissue by intraarticular injection of a radioactive agent (yttrium-90,

gold-198, phosphorus-32, and rhenium-186). It requires only one

session, but has a higher cost (Box 26.1-2). A

possible concern is that the damaging effects of the radioactivity are

not strictly limited to the synovium but may also affect the articular

chondrocytes. In addition, there is a theoretic concern of future

oncogenesis (Fig. 26.1-5).

-

A minimal requirement of antihemophilic factor

-

Performance on an outpatient basis

-

Concurrent treatment of several joints

-

Low risk of hemorrhage in patients with inhibitors

-

Administration of local anesthetic only,

which is beneficial in patients who are not candidates for surgery

because of systemic illness -

Low cost

D-penicillamine, and osmic acid. Rifampicin is commonly used with

successful results for chemical synovectomy in developing countries

where there is a lack of radioactive materials. However, it is quite

painful during injection and must be injected weekly, with the number

of injections ranging from 5 (in ankles and elbows) to 10 (in knees).

Osmic acid is another agent for using chemical synovectomy, but its

results are no better than those of rifampicin.

total joint replacement. Disabling pain with advanced destruction of

articular cartilage is the prime indication for surgery. It has been

done routinely for knees, hips, and shoulders and sporadically for

elbows and ankles. The problems of arthroplasty in hemophiliacs are

considerable and include difficulties with lack of bone stock,

deformities of the joint, muscle contractures, adhesions, and soft

tissue contractures. The most common cause of failure is infection. It

is difficult to salvage prostheses complicated by infection. However,

the life expectancy of hemophilic patients is lower than that of the

general population of patients treated with total knee arthroplasty,

and the improvement in the quality of life after knee arthroplasty for

hemophilic arthropathy may outweigh the risk of failure.

V hemophiliac arthropathy when pain is persistent with severe

disability not relieved by conservative measures. The most common

problem is aseptic loosening of cemented components, probably because

of microhemorrhages at the bone-cement surface. Studies suggest that

arthroplasty, particularly of the hip and knee, can be a valuable

option in the management of severe hemophilic arthropathy although

complications are commonly described and the surgery is technically

demanding.

joints in which arthroplasty has failed or become infected. Arthrodesis

of the ankle, subtalar, and midtarsal joints in the foot, elbow, or

shoulder may be indicated when these joints are destroyed.

possible, fractures are treated by closed reduction and immobilization

in a cast. External fixators should be avoided. Open reduction and

internal fixation are carried out when closed methods are not

appropriate.

accessible. Prior to surgical intervention, angiography, computed

tomography, and nuclear MRI should be performed to provide accurate

anatomic detail of adjacent vessels. Rarely, radiotherapy may be

considered in surgically inaccessible sites.

|

|

Figure 26.1-5 Right elbow lateral plain radiograph (A) and coronal magnetic resonance image (B) of an 8-year-old boy with hemophilia A and recurrent bleeding approximately eight times a year despite factor treatment. (C) Right elbow P-32 radioisotope synovectomy was performed.

|

F, Rivas S, Viso R, et al. Synovectomy with rifampicine in hemophiliac

haemarthrosis. Haemophilia 2000;6:562-565.

WB, Wilson FC. The management of musculoskeletal problems in

hemophilia. Part II (Pathophysiologic and roentgenographic changes in

hemophilic arthropathy). AAOS Instr Course Lect 1983;32:217-233.

G, Gilbert MS, Abdelwahab IF. Hemophilia: evaluation of musculoskeletal

involvement with CT, sonography, and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol

1992;158:119-123.

EC, Wiedel JD. General principles and indications of synoviorthesis

(medical synovectomy) in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2001;7(Suppl 2):6-10.

F. Hematologic disorders. In: Pediatric orthopaedic deformities—basic

science, diagnosis, and treatment. San Diego: Academic Press,

2001:909-933.

HJ, Luck JV Jr, Siegel ME, et al. Phosphate-32 colloid radiosynovectomy

in hemophilia: outcome of 125 procedures. Clin Orthop 2001;392:409-417.

hemoglobinopathies, which cause chronic hemolytic anemia,

immunosuppression, and pain and organ damage secondary to vascular

occlusion. Variants include sickle cell anemia (SCA), hemoglobin SC

disease, and hemoglobin S β-thalassemia. SCA is the most common form,

and can present with numerous musculoskeletal manifestations and

complications. The diagnosis and management of the musculoskeletal

problems associated with SCA can pose a considerable challenge to the

orthopaedist.

inherited genetic mutation that codes for the substitution of normal

adult hemoglobin (HbA) with sickle hemoglobin (HbS), or less commonly,

with another variety of abnormal hemoglobin. Normal HbA consists of two

α-polypeptide chains and two β-polypeptide chains. In HbS, a mutation

on chromosome 11 substitutes valine for glutamine in the sixth amino

acid position of the β-globin chain. Children who are homozygous for

the mutation have SCA; heterozygotes have sickle cell trait (SCT).

people) have SCT, and approximately 1 in 400 has SCA. In regions where

malaria is endemic, the incidence of SCT can be as high as 40%, since

heterozygotes have slightly increased resistance to malaria.

Individuals of a variety of other ethnicities (Mediterranean, Asian,

Hispanic, and Middle Eastern) may also inherit the trait or disease.

The total number of persons in the United States with a clinically

manifest variant of sickle cell disease is about 72,000.

|

TABLE 26.2-1 CLASSIFICATION OF SICKLE CELL ANEMIA

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

which changes it from a liquid to a gel. The orientation of the

hemoglobin S molecules into longitudinal fibers, combined with their

decreased plasticity due to increased viscosity, is what causes the

characteristic sickling of the erythrocytes. The presence of other

forms of hemoglobin mitigates the severity of the sickling. That is why

heterozygotes, whom have a significant proportion of HbA, are

clinically asymptomatic, except under conditions of severe hypoxia.

Similarly, sickle cell disease does not clinically manifest itself in

children under the age of 1 year, since fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which

persists until that time, is protective. Even other abnormal

hemoglobins, such as those with the thalassemia mutation, which

decreases the amount of β-globulin produced, generally are less

severely affected than HbSS homozygotes.

polymerization include dehydration, increased temperature, and falling

pH. Though sickling is reversible, repeated episodes cause cell

membrane damage that leads to permanently sickled cells. These cells

are hemolyzed intravascularly or in the spleen. The average life span

of a red blood cell in a patient with SCA is only 10 to 30 days (120

days is normal). The relative inelasticity of the sickled cells (and

even nonsickled cells with increased amounts of polymerized HbS) causes

increased blood viscosity, and decreased blood flow rate; this

contributes to occlusion and infarction of the microvasculature.

disease is a hemoglobin electrophoresis. The different disease variants

have characteristic electrophoresis patterns. A 5-minute solubility

test, called a Sickledex, can be used in initial screening, or in an

emergency setting, but if it is positive, an electrophoresis needs to

be done to differentiate between a carrier and disease state. The

Sickledex also has a relatively high false-negative rate.

result of vascular occlusion, hemorrhage, infarction, and ischemic

necrosis secondary to increased blood viscosity caused by sickling.

They can be summarized by use of the mnemonic HBSS PAIN CRISIS (problems for which an orthopaedist is frequently consulted are highlighted in italics):

-

Affects short tubular bones of hands and feet

-

Age 6 to 12 months (when HbF is replaced by HbS)

-

Distal extremities become swollen, tender, and painful

-

Triggered by cold weather

-

Lasts 1 to 2 weeks

-

Incidence: 45%

-

Recurrence: 41%

-

Rare after 6 years of age (when marrow activity in hands/feet ceases)

-

Dactylitis

-

Avascular necrosis

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Septic arthritis

-

Growth retardation

-

Leg ulcers

-

Bone marrow hyperplasia

-

Increased tendency to fracture

-

Age between 3 and 4 years

-

Lasts 3 to 5 days

-

Localized bone marrow or muscle infarction secondary to sequestration of sickled cells

-

Commonly: humerus, tibia, femur

-

Clinically: swelling, decreased range of motion, increased temperature

-

Clinically: fever, pain, swelling

-

Polyostotic: 12% to 47%

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate unreliable (usually low) secondary to sickled red blood cells

-

Staphylococcus aureus and MRSA common, but patients also susceptible to encapsulated organisms secondary to decreased splenic function:

-

□ Streptococcus pneumoniae

-

□ Haemophilus influenzae

-

□ Salmonella

-

□ Meningococcus

-

□ Klebsiella

-

-

Septic and reactive arthritis are less common than osteomyelitis but do occur

-

Joint fluid in reactive arthritis will show less than 20,000 white blood cells/mm3

-

Can lead to destruction of the physis, growth arrest, and limb deformity

-

Incidence: 8%

-

May be hemorrhagic or infarct

-

Greater than 50% recurrence rate, unless chronic life-time transfusion therapy instituted

-

May result in spastic hemiplegia requiring orthopaedic management

-

May be secondary to bone marrow hyperplasia, osteomyelitis, or disuse osteopenia

-

Attempt to minimize immobilization during treatment to prevent recurrence

-

Femoral head most common, followed by humeral head

-

Incidence: approximately 10%; bilateral: 54%

-

Usually diagnosed on plain x-ray, but magnetic resonance imaging may be useful to show extent of head involvement

by a hematologist, the systemic nature of the illness and the clinical

manifestations in various organ systems practically guarantee that most

patients will also be treated by a variety of other subspecialists. The

various acute crises and complications common to the disease often

necessitate presentation in the emergency department as well. Treatment

of patients with SCA can be thought of in three groups: preventive,

problem management, and systemic.

-

Daily supplemental folate, to keep up with red blood cell production demand

-

Periodic complete blood count check, to catch changes/problems early

-

Use supplemental iron sparingly; iron overload can become a problem in older patients

-

Maintain immunizations

-

Encourage adequate oral hydration

-

Encourage patients to seek early medical attention when ill

-

Discourage smoking and alcohol intake

-

Discourage excessive physical exertion

-

Avoid extremes of temperature

|

TABLE 26.2-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SICKLE CELL ANEMIA

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

|

TABLE 26.2-3 DIAGNOSIS BASED ON SEQUENTIAL BONE MARROW AND BONE SCANS RESULTS

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

-

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for chronic pain

-

Analgesia with NSAIDs/narcotics

-

Hydration

-

Bed rest

-

Identify and correct underlying precipitators (especially infection)

-

Administration of oxygen, and monitoring, if the patient has documented hypoxemia

-

Antibiotic coverage for S. aureus and Salmonella

-

Surgical drainage for chronic

osteomyelitis with sequestrum formation, or for patients who are

systemically septic or not responding to antibiotic therapy

-

Arthrotomy and drainage, in conjunction with antibiotics

|

TABLE 26.2-4 PROBLEM MANAGEMENT IN AVASCULAR NECROSIS

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-

Dose 1 to 35 mg/kg/day (see Table 26.2-5 for pros and cons)

-

Simple transfusion to hemoglobin level of 10 g per dL now preferred over exchange transfusions for preoperative optimization.

-

Use of antigen-matched blood and adequate

hydration/oxygenation helps prevent complications during transfusion

therapy and postoperatively. -

Acute transfusions are indicated for life-threatening complications of SCA such as stroke and aplastic anemia.

-

Chronic transfusion therapy for life is indicated to prevent recurrent strokes.

|

TABLE 26.2-5 PROS AND CONS OF ORAL HYDROXYUREA THERAPY

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

-

By use of transcranial Doppler ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography

-

15% of patients have asymptomatic CNS ischemic injury

-

Trials ongoing to establish role of transfusion therapy for prevention of CNS ischemic injury

AR, Roberson JR, Eckman JR, et al. Total hip arthroplasty in patients

who have sickle-cell hemoglobinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am)

1988;70:853-855.

WW. Pathological fracture complicating long bone osteomyelitis in

patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Orthop 1986;6:177-181.

CA, Hughes JL, Abrams RC, et al. Osteomyelitis in the patient with

sickle-cell disease. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1971;53:1-15.

P, Bachir D, Galacteros F. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head in

sickle-cell disease: treatment of collapse by the injection of acrylic

cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1993;75:875-880.

SL, Cotran RS, Kumar V. Sickle cell disease: pathologic basis of

disease, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1984:618-622.

DL. Differentiation between bone infarction and acute osteomyelitis in

children with sickle-cell disease with use of sequential radionuclide

bone-marrow and bone scans. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001;83:1810-1813.

MC, Padwick M, Serjeant GR. Observations on the natural history of

dactylitis in homozygous sickle cell disease. Clin Pediatr

1981;20:311-317.

MC, Patience M, Leisenring W, et al. Marrow transplantation for sickle

cell disease: results of a multicenter collaborative investigation. N

Engl J Med 1996;355:369-376.