Nonacute Shoulder Disorders

-

Anatomy. The

muscle tendon units of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres

minor compose the rotator cuff. Each has its own specific muscle body

but they coalesce together into one tendon as they pass through the

subacromial space. The borders of the subacromial space are as follows:

superiorly, the undersurface of the acromion and the acromioclavicular

(AC) joint; anteriorly, the coracoacromial ligament and coracoid;

inferiorly, the humeral head. The subacromial bursa also exists in the

subacromial space above the rotator cuff but underneath the acromion.

The long head of the bicep tendon and the subscapularis muscles are

important anterior stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint. -

Mechanism of injury.

Any anatomic influences that narrow the already confining subacromial

space have the potential to compromise, in particularly, the

superspinatus tendon and irritate the SA bursa. Thickening of the

bursa, undersurface spurring of the AC joint, instability of the

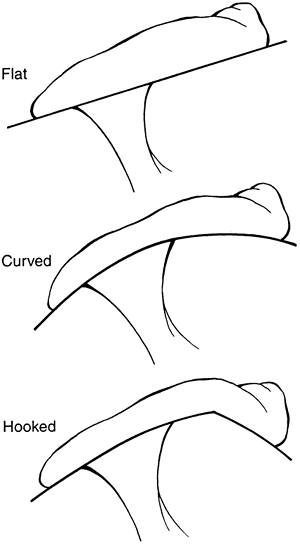

glenohumeral joint, or changes in the shape of the acromion (Fig. 16-1) are the most common reasons for rotator cuff compromise. This process of rotator cuff attrition is manifested as impingement syndrome.

The process of cuff disease begins with bursitis and reversible

tendinosis and gradually progresses to full-thickness cuff pathology

over time. -

History. The

typical patient with impingement syndrome is older than age 40 and

complains of anterolateral shoulder pain, which is worse with overhead

activities and positionally at night. -

Examination.

Examination begins by general inspection of the anterior and posterior

shoulder. Clearly visible atrophy of the posterior shoulder in the

region of the supraspinatus and/or infraspinatus muscle belly is an

indicator of a large rotator cuff tear. The differential diagnosis for

this atrophy would include suprascapular nerve entrapment. Shoulder

motion is often symmetric except for a loss of internal rotation.

Special tests include those for rotator cuff strength, impingement, and

instability. Supraspinatus weakness and pain is usually present to

strength testing. Tenderness is present over the anterior rotator cuff

and SA bursa. Significant weakness to external rotation strength

testing often indicates that a large rotator cuff tear is present. -

Roentgenograms.

Plain roentgenograms should be obtained in patients with a history of

acute trauma or in those who do not improve with standard nonoperative

treatment. Sclerosis of the greater tuberosity, narrowing of the

acromiohumeral distance, or spur formation at the AC joint or the

anterior acromion are all evidence of ongoing impingement syndrome. An

acromion that has an inferiorly directed hook at its anterior edge is

classified as a type III acromion (1) (Fig. 16-1).

This hooked acromion may predispose some patients to developing

anterior rotator cuff pathology by narrowing the SA space. Usually the

supraspinatus tendon is affected first. With patients in whom operative

intervention is indicated, further imaging studies may be obtained.

Arthrograms are widely available and easily used to detect the presence

of a rotator cuff tear. However, they do not give reliable information

regarding tear location, size, atrophy, or other associated subacromial

pathology. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, gives more detailed

information regarding pathology in the SA space. It is more expensive

and may be susceptible to technical problems and misinterpretation. An

MRI

P.230

should only be ordered if it will change treatment recommendation (Table 16-1).

Physicians without adequate experience in the shoulder exam may wish to

refer prior to ordering the MRI. Ultrasonagraphy is another diagnostic

test that can, in the hands of an experienced ultrasonagrapher, give

good visualization of rotator cuff pathology. Figure 16-1.

Figure 16-1.

Bigliani classification of acromial morphology: type I, flat; type II,

curved; type III, hooked. (From Bigliani LU, Morrison DS, April EW. The

morphology of the acromion and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Trans 1986; 10:288.) -

Diagnosis.

The topic of nonacute shoulder disorders often falls into the broad

categories of impingement and instability. While the former tends to

affect people older than age 30, and instability tends to affect those

younger than age 30, there is a large overlap. Additionally, both may

occur in the same patient. Impingement is generally the result of

either some bursitis, tendinopathy, or rotator cuff tears. These issues

will be addressed below. Instability, or a hyper-mobile glenohumeral

joint was addressed under the topic of shoulder dislocations in Chap. 15, II.C. Additional categories of

P.231

AC joint arthritis, adhesive capsulitis, arthritis, and scapulothoracic

disorders are causes of non-acute shoulder disorders and will be

discussed below.TABLE 16-1 MRI Scan Indications- Shoulder dislocation over age 40.

- Significant rotator cuff weakness.

- Family history of rotator cuff disease.

- Failure to respond to nonsurgical measures (physical therapy, injection).

-

Treatment

-

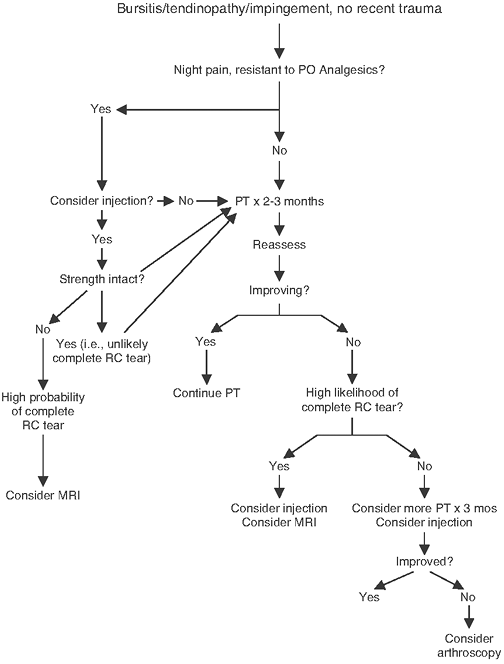

Bursitis/tendinopathy/impingement (Fig. 16-2).

The focus of treatment for chronic shoulder disorders is physical

therapy (PT). PT forms the basis for recovery for those who suffer from

impingement-type symptoms (e.g., with bursitis or rotator cuff

tendinopathy), instability, adhesive capulitis, scapulothoracic

dysfunction, and other nonacute shoulder pathology. The current

P.232

standard

for successful treatment is on returning the patient to his or her full

range of motion prior to focusing on strength. Poor posture associated

with our increasingly inactive lifestyles seems to be cause of poor

scapulothoracic stability and subsequent shoulder pain. It is important

to ask your physical therapists to address scapular stabilization in

the rehabilitation of most patients with chronic shoulder problems. The

scapula forms the starting point of the rotator cuff muscles (thus

important in rotator cuff tendinopathy), the origin of the acromion

(thus important in other causes of impingement), and of the glenoid

(thus important in shoulder instability). Our personal preference is

for the patient to have at least 6 to12 months of concentrated PT prior

to surgery unless otherwise indiciated (e.g., if there is a complete,

acute rotator cuff tear).![]() Figure 16-2.

Figure 16-2.

Diagram of treatment pathway for bursitis/tendinopathy/impingement with

no recent trauma. PT, physical therapy; RC, rotator cuff.Injections provide another important component in the treatment of nonacute shoulder problems (Table 16-2).

The most common is an SA injection, for which we prefer a

posterolateral approach due to its ease and avoidance of major

neurovascular structures (see chapter on injections for details). The

SA shoulder injection can be done with either diagnostic or therapeutic

goals. Diagnostically, one can theoretically “rule out” a complete

rotator cuff tear if a patient who had pain and weakness demonstrates

normal strength after an anesthetic injection. Therapeutically, pain

relief from an injection is for those who have pain that cannot be

treated adequately with oral medications (either due to a lack of

efficacy or side effects), those who are unable to perform PT due to

pain, and those with night pain that interrupts their sleep.-

Nonoperative treatment is successful in the majority of patients. The cornerstone of treatment is Physical therapy

to rehabilitate the rotator cuff muscles (especially the

supraspinatus), to regain scapulothoracic stability, and to correct any

contractures (typically loss of internal rotation). If physical therapy

alone is not successful, an injection of

corticosteroid and lidocaine into the SA space often brings the

patient’s symptoms under control. If the diagnosis of impingement

syndrome is correct, the lidocaine should give an excellent relief of

pain for 2 to 3 hours. If no lidocaine effect is obtained, alternative

diagnoses should be considered. The steroid typically takes 2 to 4 days

to take effect. The indications for an SA injection at the initial

visit include significant night pain or symptoms severe enough to make

progress in PT difficult. -

Operative treatment

is indicated in individuals who fail a minimum 6-month course of

nonoperative treatment. The goal of surgery is to open the SA space.

This is typically accomplished by excision of the thickened and

P.233

scarred

bursa, recession of the coracoacromial ligament, and an anterior

acromioplasty. Any other factors (AC joint hypertrophy or glenohumeral

instability) that may predispose the patient to impingement syndrome

should also be addressed. This opening of the SA space is termed a decompression.

A decompression may be completed through either open or arthroscopic

techniques. Arthroscopic techniques allow an evaluation of the

glenohumeral joint for any concomitant pathology. In addition, a

patient with an arthroscopic SA decompression recovers approximately 1

month sooner than an open SA decompression.

-

-

Rotator cuff tears

-

Younger patients

(younger than 55 years old) or those with true acute tears typically

undergo surgical repair. Repairs for complete tears are best done if

within 3 months of injury when possible. -

Older patients

often do well with physical therapy and nonoperative treatment. MRI

studies of asymptomatic patients older than 60 years of age have shown

that 50% have some form of rotator cuff pathology. An SA decompression

and rotator cuff repair are indicated only after nonoperative measures

have failed. In older, low functional demand patients with large

rotator cuff tears, an SA decompression alone often yields good pain

relief, but only limited improvement in function. Patients with a

massive, irreparable rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral arthritis often

respond well to physical therapy and an SA injection. If nonoperative

treatment fails, arthoscopic glenohumeral joint debridment and limited

SA decompression may be indicated. A hemi-arthroplasty is another

acceptable form of operative intervention.

-

-

Calcific bursitis.

involves deposition of a calcium salt into the substance of the rotator

cuff tendon. This paste-like material may escape into the SA bursa,

causing an acute inflammatory bursitis. Severe symptoms of impingement

syndrome result. An SA injection with corticosteroids with lidocaine

and PT are effective in controlling acute symptoms. If repetitive

episodes of pain occur, an arthroscopic excision of the calcific

deposit is indicated. -

Long head of biceps tendinitis (see Chap. 15, IV) often occurs as part of impingement syndrome and is treated with the same program.

-

range of motion may have a problem with their glenohumral joint, either

a bony obstruction (arthritis) or a capsular adhesion (adhesive

capsulitis or “frozen shoulder”). Note that these two problems can be

distinguished from a rotator cuff tear by noting differences between

active and passive range of motion. A patient with a rotator cuff tear

may have more passive than active range of motion, whereas, one with

true glenohumeral pathology will have equal passive and active range of

motion (Table 16-3).

-

Arthritis

-

Etiology.

Arthritis of the glenohumeral joint may be idiopathic (osteoarthritis),

secondary to inflammatory disease (rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis),

or posttraumatic. Given that the shoulder is not a weight-bearing

joint, symptomatic arthritis of the

P.234

glenohumeral joint is not as common as arthritis of the knee and hip.TABLE 16-3 Diagnostic Range of MotionEtiology Range of motion Full thickness rotator cuff tear Passive may be greater than active Osteoarthritis Passive = Action Adhesion capsulitis Passive = Action -

History.

Nonspecific lateral shoulder pain is present, which is made worse with

increased activities. Stiffness is also a frequent complaint.

Polyarticular complaints should arouse the suspicion of an inflammatory

disorder. -

Examination

reveals loss of active and passive range of motion, crepitus on joint

motion, and mild diffuse muscle atrophy. Strength is usually not

significantly affected. Distal neurovascular changes are rare. -

Roentgenographic

studies should include an anteroposterior view of the shoulder in 30

degrees of external rotation and an axillary view. Narrowing of the

glenohumeral joint space and inferior spur formation on the humeral

head is an indication of osteoarthritis. Periarticular erosions are

suspicious for inflammatory disease. A computed tomography scan to

exactly determine glenoid version or an MRI scan to assess rotator cuff

status and glenoid version may be indicated preoperatively. -

Treatment

-

Nonoperative treatment

is directed toward controlling the pain with analgesics, injections of

the glenohumeral joint with anesthetics and corticosteroids, and

improvement of joint mechanics (especially range of motion) with PT and

lifestyle modification. -

Operative treatment.

In early cases of inflammatory arthritis, an arthroscopic synovectomy

may yield improvement of symptoms. Once the articular surface is eroded

to bone, either a hemiarthroplasty, a total shoulder replacement, or an

arthrodesis is indicated. A total shoulder replacement results in the

best function of the glenohumeral joint and pain relief (2) but may not be indicated in young patients or patients with heavy occupational demands.

-

-

-

Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)

-

Etiology

-

Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis results

from capsular fibrosis. The pathologic mechanism for this fibrosis is

not well understood (3). -

Adhesive capsulitis may result from

capsular fibrosis from a traumatic or surgical event or may be

associated with a systemic disease such as diabetes, thyroid disorders,

cervical disc disease, or neoplastic disorders of the thorax.

-

-

History. The

patient complains of a deep, achy pain in the shoulder that is present

at rest as well as with activities. Complaints of loss of motion follow

the onset of the pain by several weeks. A careful past medical history

and review of systems is necessary to rule out any systemic causes.

Diabetes mellitus and thyroid abnormalities often predispose people to

adhesive capsulitis. Distal neurovascular complaints are rare. -

Examination.

A global loss of active and passive range of motion is noted. Internal

and external rotation are typically affected first. Nonspecific

tenderness is usually present early in the disease process. Rotator

cuff strength is often normal but may be difficult to assess secondary

to the limited and painful range of motion. -

Roentgenographs are typically unremarkable.

-

Treatment

-

Nonoperative

management with a home-based stretching program as well as pain

medication if necessary is successful in 90% of patients. Symptoms may

take up to 18 months to resolve. Occasionally, an injection of the

glenohumeral joint with corticosteroid is necessary to control pain (4). -

Operative treatment

is directed at releasing the contracted capsule in a sequential fashion

to improve range of motion. This may be accomplished either closed or

arthroscopically. Any associated pathology (especially in the SA space)

should also be addressed (5). Operative intervention typically not indicated until the patient fails 12–18 months of nonoperative care.

-

-

-

Arthritis

-

Etiology. Osteoarthritis of the AC joint is extremely common in individuals older than 50 years of age and most are asymptomatic (6). Inflammatory

P.235

processes such as rheumatoid arthritis or fractures of the distal

clavicle can also cause AC joint symptoms. Younger patients may develop

nonacute AC joint pain from activities such as weight lifting. -

History. Pain

is localized to the superior aspect of the AC joint. Symptoms are worse

when sleeping on the affected side. Overlap symptoms with impingement

syndrome are common. -

Examination.

Tenderness over the subcutaneous aspect of the AC joint is present. The

extreme motions of forward flexion and cross body adduction are limited

and painful. Frequently, coexisting rotator cuff findings are present. -

Roentgenograms are similar to those obtained for patients with impingement syndrome. A Zanca view is helpful.

-

Treatment is

directed at controlling local symptoms with PT, analgesics, and, if

necessary, a corticosteroid and lidocaine injection into the AC joint.

A typical AC joint will accept 1 to 2 cc of volume. If nonoperative

treatment fails, a distal clavicle resection is indicated. This may be

completed either via arthroscopic or open techniques (7).

-

-

Osteolysis of

the clavicle may occur following a traumatic injury to the AC joint or

in individuals who place repeated unusual stress on the AC joint, such

as weight lifters. Radiographic changes consist of osteopenia and

erosive changes in the articular surface. Treatment is similar to that

described for arthritic conditions.

-

Scapulothoracic bursitis (snapping scapula)

-

Etiology. The

scapula has a significant excursion across the chest wall with range of

motion of the shoulder girdle. This motion requires the presence of a

large bursa between the scapula and the thorax. Inflammation of this

bursa can be caused by overuse of the shoulder, serratus anterior

contracture, or a bony deformity on the undersurface of the scapula (8). -

History.

Patients complain of pain deep and medial to the scapula on the thorax

posteriorly. The hallmark symptoms of this disorder are catching or

crepitus with motion of the scapula. -

Examination. Scapulothoracic motion may be limited. The patient can usually reproduce a palpable sensation of crepitus under the scapula.

-

Imaging studies are not typically useful unless there is a history of trauma or there is suspicion of an osteochondroma under the scapula.

-

Treatment is

directed at increasing motion of the superior medial angle of the

scapula away from the thorax and strengthening the periscapular

muscles, or noninvasive techniques may include deep friction massage

and ultrasound. Occasionally, a corticosteroid injection into the

scapulothoracic bursa is necessary. If nonoperative methods fail, an

arthroscopic or open excision of the bursa and the superior medial

angle of the scapula is indicated (9).

-

-

Winging of the scapula

-

Etiology. The

scapula is held against the thorax by the serratus anterior muscle,

which is innervated by the long thoracic nerve. Anything that disrupts

either of these two structures results in winging of the scapula.

Pseudo-winging of the scapula (scapular dyskinesia) is far more common

than true winging and develops when the periscapular muscles do not

work in a synchronized manner. -

History.

Weakness and loss of active motion of the shoulder is noticed first.

Secondary symptoms of rotator cuff inflammation (secondary impingement

syndrome) may develop. A history of trauma to the chest wall in the

location of the long thoracic nerve may be present. Most patients do

not have a readily identifiable cause for their serratus anterior

dysfunction (10). Fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy often initially presents with isolated winging of one or both scapulae. -

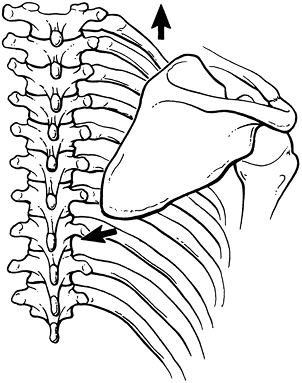

Examination.

Winging of the scapula occurs when the medial border of the scapula is

rotated outward and laterally, causing the scapula to give the

appearance of “wings” on the patient’s back (Fig. 16-3). Figure 16-3.

Figure 16-3.

Position of the scapula with primary scapular winging due to serratus

anterior palsy. The scapula pulls away from the back and does not

protract on arm elevation. (From Kuhn JE, Hawkins, RJ. Evaluation and

treatment of scapular disorders. In: Warner JJP, Iannotti JP, Gerber C,

eds. Complex and revision problems in shoulder surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1997: 357–375.) -

Treatment is

directed at strengthening the periscapular muscles and observation to

determine whether the long thoracic nerve will recover. If after 18

months no recovery is present, either a pectoralis major tendon

transfer or a scapulothoracic fusion is indicated.

P.236 -