Foot Problems in Children

|

|

|

|

How some parents seem to see their children

Adapted from Wenger DR, Rang M, eds. The Art and Practice of Children’s Orthopaedics. New York: Raven Press, 1993.

|

infants, due in part to excessive subcutaneous fat, but also due to

true valgus alignment of the bones and joints. As part of development,

the longitudinal arch of the foot becomes more pronounced and the fat

disappears. Flatfoot is present in 23% of adults, and is usually

asymptomatic.1 The key to staying

out of trouble with this condition is in recognizing that the flatfoot

is a normal foot shape in most affected children and adults (Fig. 25-1).

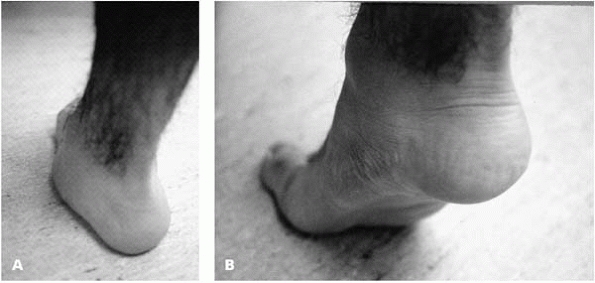

It is also important to differentiate flexible flat feet from

pathologic flat feet. This is accomplished by observing the appearance

of an arch when a flatfooted child stands up on the toes, or is

non-weight bearing with the foot dangling in the air. It is also

vitally important to verify hindfoot motion, which can also be done by

observing the child rising up to stand on the toes, as the flexible

hindfoot will move from a valgus to varus position (Fig. 25-2).

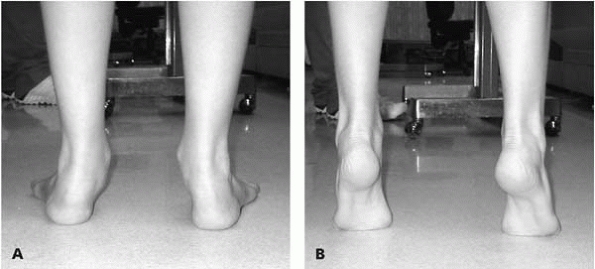

Hindfoot mobility can also be assessed by cupping the heel in the

examiner’s hand and shifting from side to side (inverting and everting)

(Fig. 25-3).

|

|

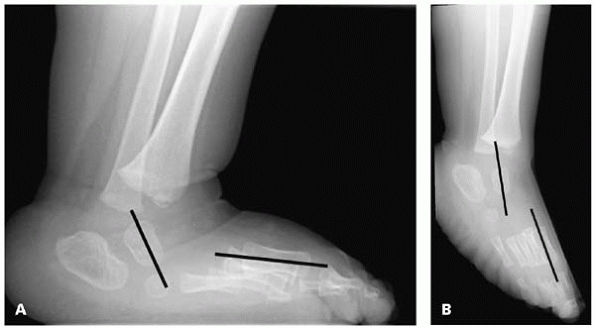

▪ FIGURE 25-1 (A) In normal weight-bearing position, this patient has a very flat foot. (B) When standing on his toes, the arch is visible. This dynamic change with foot position defines a flexible flatfoot.

|

toes, or the hindfoot is not mobile, the child does not have a flexible

flat foot. Causes of rigid flatfoot include tarsal coalition, vertical

talus, neuromuscular condition, inflammatory arthritis, infection, etc.

An easily overlooked part of flatfoot assessment is contracture of the

Achilles tendon. This can be evaluated by passively dorsiflexing the

ankle while holding the subtalar joint in a neutral-to-slight varus

position, with the knee in full extension. If, when tested in this

manner, at least ten degrees of ankle

dorsiflexion

is not possible, the child will frequently complain of pain under the

medial midfoot. A painful flatfoot with a tight Achilles tendon

warrants treatment.

|

|

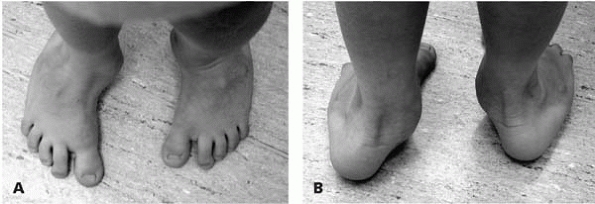

▪ FIGURE 25-2 (A) Patient with flatfeet and hindfoot valgus. (B)

When standing on the toes, the hindfoot goes into varus, proving the hindfoot is mobile, and the arch elevates, thus confirming a flexible flatfoot. |

the first manifestation of a syndrome such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome,

Marfan, Morquio, Down, cri-du-chat, fragile X, and others.

diagnosed, share with the parents that this is not a problem, but a

normal variation. It may be helpful to share with parents that studies

of both military recruits and grocery store employees who are on their

feet much of the day found that flexible flatfeet are not a source of

disability in adults.1,2 It has been shown that wearing corrective shoes or inserts does not influence the course of flexible flatfoot in children.3

Furthermore, wearing shoe modifications during childhood has been shown

to be a negative experience and associated with lower self-esteem in

adult life.4 While not prescribing “something” may get you in trouble with the parents, above all we must do not harm to the child.

flatfeet are prescribed orthotics. As one consultation letter from a

non-MD explains “Nontreatment for this condition could result in

further subluxation of the joints, producing symptoms in adulthood

including low back discomfort, weakness, instability, bunions,

hammertoes and internal foot problems” and the child may not get into

Harvard. This belief of the evilness of flatfeet may be widespread in

parts of your community. Stay out of trouble by finding out what

opinions your parents may have heard before seeing you.

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-3 Hindfoot mobility can be assessed by cupping the heel and shifting it from side to side (inverting and everting).

|

under an already flat foot may cause discomfort, particularly in those

with an Achilles tendon contracture. Children who have undergone

orthotic-ectomies with complete relief of pain and guilt are among our

most grateful patients.

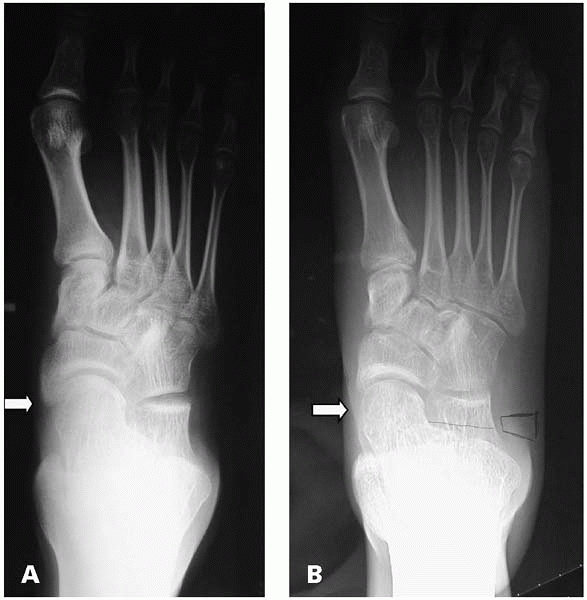

flatfoot. We should treat symptoms, not deformity. Painful flexible

flatfeet may be associated with an accessory navicular, tight heel

cords, or other conditions. It is essential that foot radiographs are

taken with the child bearing weight (Fig. 25-4), and be aware that

many of the radiographs patients bring with them will not be.

Over-the-counter soft shoe inserts, available at many sporting good

stores, will often relieve symptoms of diffuse foot aching. Consider

surgery only as the last resort. Avoid fusions, as the calcaneal

lengthening osteotomy has good results and preserves subtalar motion.5

Synthetic implants have been used frequently by non-physician

healthcare providers, and we have seen disasters. We recommend staying

away from implants until they have been shown to be equal in safety and

efficacy to the calcaneal lengthening osteotomy.

|

|

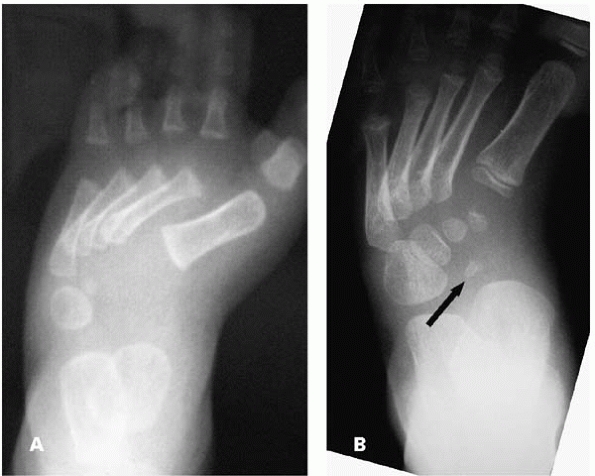

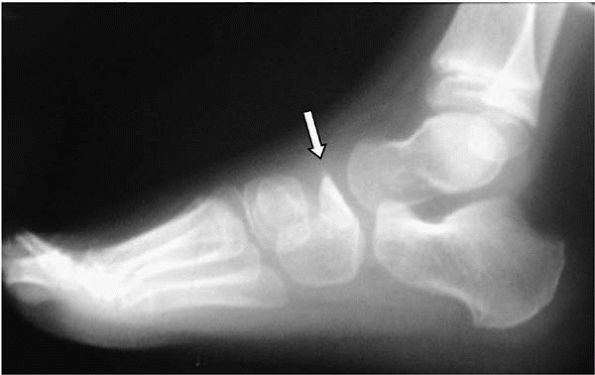

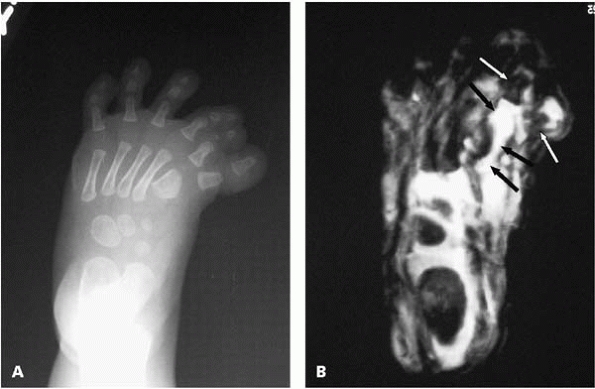

▪ FIGURE 25-4 (A) Non-weight bearing AP radiograph of the foot demonstrates reasonable alignment of the talonavicular joint (arrow). (B)

Weight-bearing view of the same child’s foot taken moments later demonstrates medial subluxation of the talar head relative to the navicular (arrow). |

fusions within the foot lead to degenerative changes at adjacent

joints. Fusions, and in particular triple arthrodesis, should be

avoided if possible, and used only as a last resort.6, 7, 8

Tendon transfers to address muscle imbalance and extraarticular

osteotomies should adequately manage the majority of children’s foot

deformities.

radiographs for minor trauma, and are mistaken for fractures. Remember

that more than 20% of children have at least one accessory bone that

can be seen on radiographs.9

have a symptomatic accessory navicular become asymptomatic when they

reach skeletal maturity, suggesting that surgery should be delayed and

used only as a last resort. Use of a medial longitudinal arch support

may exacerbate the symptoms by adding more pressure to the region,

whereas a UCBL (University of California Biomechanics Laboratory) shoe

insert may unweight the painful area by bringing the heel into varus

and elevating the arch of the foot. Surgical excision of the accessory

navicular without re-routing of the posterior tibial tendon has been

reported to have good results.10 However, any surgery in a painful weight-bearing region of the foot is prone to continued discomfort (Fig. 25-5).

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-5 Accessory navicular (arrow).

|

children, where the flexor hallucis longus passes in the groove along

the posterior talus. The trouble with this accessory bone is that it

can fracture and cause pain or become symptomatic in ballet dancers

presumably due to prolonged weight bearing in equinus. A fractured os

trigonum may have a rough or sharp border along the talus, in contrast

to an unfused os trigonum with a smooth border (Fig. 25-6).

|

|

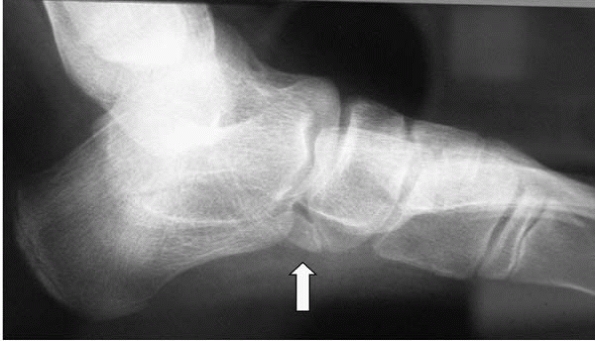

▪ FIGURE 25-6 Os trigonum (arrow). Note that the edges are smooth, suggesting that this is not a fracture.

|

the base of the fifth metatarsal where the peroneus brevis attaches is

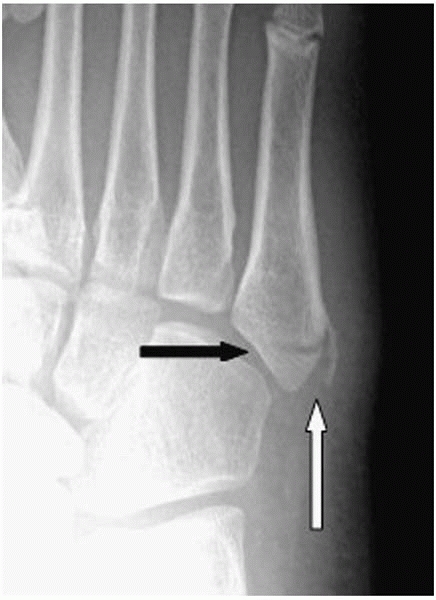

often confused with a fracture by the unknowing (Fig. 25-7).

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-7

AP radiograph of a child’s foot demonstrating the normal apophysis of the fifth metatarsal where the peroneus brevis tendon attaches (white arrow), which is more or less parallel to the long axis of the metatarsal. This normal apophysis is not to be confused with a fracture of the proximal fifth metatarsal (black arrow), which tends to occur perpendicular to the long axis of the metatarsal. |

just stick to a limited number of pitfalls. Clubfoot is frequently part

of an underlying syndrome, thus a complete history and physical is

warranted to uncover other abnormalities. Clubfoot is also associated

with tarsal coalition11 and fibular hemimelia.12

-

This problem involves the whole leg, not just the foot. The entire leg will be thinner and slightly shorter than the other.

-

Make them aware of

the Ponseti method as the recently accepted form of treatment in the

USA. Parents of patients who underwent months of casting or surgery for

clubfoot and believe a vastly superior alternative was hidden from them

can be very upset. -

Following the

standard surgical treatments that have been in common use during the

past half century, the reported rate of secondary surgery approximates

50%, and stiffness and pain have been common sequelae. -

Dynamic supination

of the foot is seen in perhaps 30% of children with clubfoot and may

require transfer of the tibialis anterior to the lateral cuneiform in

children over the age of 3 to 4 years.

All children being evaluated for musculoskeletal problems should have a

careful hip exam. Imaging of hips should be based purely on risk

factors or findings suggestive of DDH.

manipulations and cast applications which, when combined with a heel

cord tenotomy, has been reported to provide complete correction of the

idiopathic clubfoot in 95% of patients.14

In our opinion, the main pitfalls in use of the Ponseti approach result

from deviation from the prescribed technique as described by the

originator.15

-

Indications: idiopathic clubfoot and those with associated chromosomal abnormalities or ligamentous laxity syndromes.

-

Pitfalls: Pressure

sores from the manipulation and casting in patients with spina bifida

or arthrogryposis. It is important to apply the cast only to the limits

that may be obtained via manipulation.

-

Hyperpronation of

the first ray; the foot should be initially supinated. The foot should

remain supinated throughout the casting procedure; as increased

correction is obtained, the supination is decreased to a more normal

alignment. -

Maintain the foot in

equinus during the sessions of manipulation and casting. Attempting to

place the foot in a dorsiflexed position prior to correcting the

hindfoot will block the eversion and abduction of the calcaneus

underneath the talus, subsequently preventing full correction of the

clubfoot. -

Fulcrum of pressure

should be positioned over the head of the talus. Errantly positioning

pressure over the calcaneal cuboid joint16 will block the reduction of the calcaneus underneath the talus and prevent subtalar correction.

-

Casting children who are agitated. Babies are comforted with bottle-feeding during the casting procedure.

-

Long leg cast

application is always used and is integral to the success of the

method. Failure to use long leg casts will result in poor outcome. -

Not using a well-molded plaster cast as opposed to fiberglass cast material.

-

Placing too much or

too little padding around the foot and ankle. Two to three layers of

cotton roll is sufficient before application of the plaster cast. -

Casting the foot in correction beyond that obtained by manipulation.

-

Pressure in the popliteal fossa from the proximal trim line of the short leg cast when converting to the long leg cast.

-

When trimming the

cast down, don’t expose too much of the dorsal aspect of the foot

proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal joints, as this will often lead

to a tourniquet effect and swelling of the toes.

-

Performing tenotomy

before the heel is in valgus and foot abduction of greater than 60

degrees is noted. This will block the eversion of the calcaneus in the

subtalar joint and lead to midfoot breech and a rocker bottom deformity. -

Excessive dorsiflexion prior to tenotomy will result in difficulty in palpation of the Achilles tendon.

-

Injecting large amounts of lidocaine around the tendon will make palpation difficult.

-

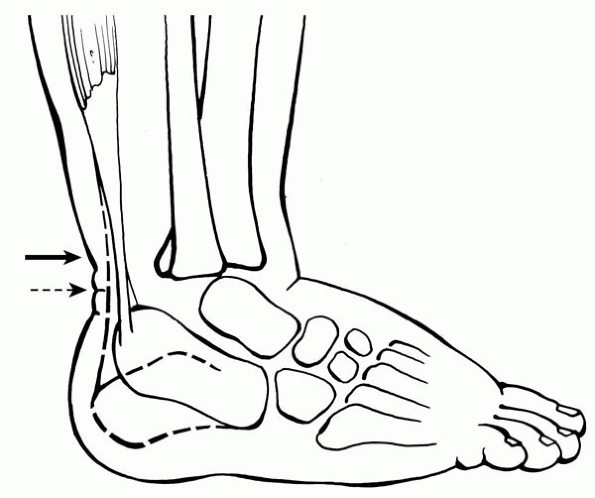

Performing a tenotomy at the cutaneous heel crease (Fig. 25-8, dashed arrow)

can be difficult and potentially detrimental, as you will be too distal

and potentially into the substance of the Achilles tendon insertion on

the calcaneus. Tenotomy needs to be approximately one half centimeter

proximal to the distal heel crease (Fig. 25-8, solid arrow). -

Incomplete tenotomy

should be suspected when there is no palpable ‘pop’ and an immediate

increase in dorsiflexion of approximately 15 to 30 degrees. The tendon

should be revisited with the knife to complete the transection. -

Transection of local venous structures, and presumably the peroneal artery, has been noted.17

When excessive bleeding occurs, simple pressure on the heel cord for an

additional 3 to 4 minutes before placing in a long leg cast is usually

all that is necessary.

-

Noncompliant use of the abduction orthosis.14,18 Successful use of an orthosis is associated with prevention of deformity recurrence.

-

Errors in fitting of

the abduction orthosis include deviation from the shoulder width

positioning of the shoes and standard external rotation of the feet of

50 to 60 degrees. -

Pressure sores can

result from poor fit of the shoes. For the first week the skin should

be checked at each diaper change to detect and treat potential blisters

or other pressure phenomena.

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-8

|

should be the number one priority. Absence or a substantial reduction

in the size and flow of the anterior tibial artery occurs in

approximately 90% of limbs with clubfoot. Preservation of the posterior

tibial artery should be a surgeon’s number one priority. One should

consider not fully exsanguinating the foot prior to tourniquet

inflation in order to visualize the posterior tibial neurovascular

bundle. Although uncommon, the posterior tibial artery may be absent in

a clubfoot.19 If the posterior

tibial vascular bundle cannot be located at the time of surgery, even

after the tourniquet is taken down, a hypertrophied peroneal vascular

bundle may be present, and should be carefully identified and protected.

-

In order to correct equinus of the calcaneus, the calcaneofibular ligament must be sectioned.

-

Leave wound open if needed—otherwise bringing the foot out of equinus may be difficult and require serial postoperative casting.

-

Do not cut the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament—otherwise lateral translation of calcaneus is a disaster.

-

Do not position the navicular dorsal to the talar head, as that is associated with a poor outcome.20

-

Part of syndrome? Arthrogryposis.

-

Unossified bones make radiograph interpretation unreliable.

-

When releasing the talonavicular joint, aim distally or risk cutting across the talar neck.

-

Make Cincinnati incision at least 1 cm proximal to heel crease or risk heel slough if more distal.

-

Isolate neurovascular bundle early in the procedure.

|

|

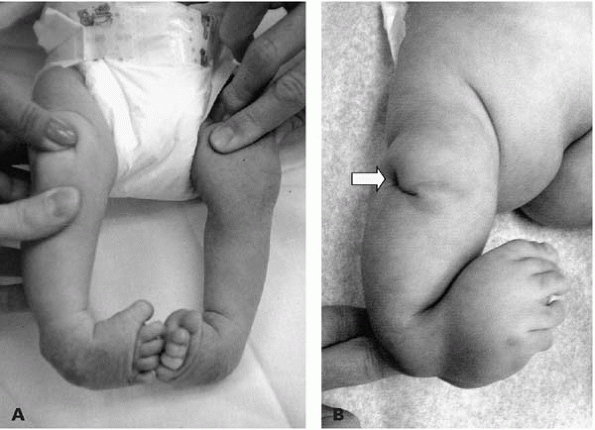

▪ FIGURE 25-9 (A) Baby with bilateral clubfeet. (B) Baby with tibial hemimelia. Note that the dimple over the knee (arrow)

is a red flag that there is an underlying osseous disorder. Dimples are often seen over the apex of the tibial bow in fibula hemimelia. |

point out that ankle valgus is common in children with clubfoot, and

recommend a weight-bearing anteroposterior radiograph of the ankles in

children presenting with clubfoot “overcorrection.” When ankle valgus

is the cause of hindfoot valgus, a hemiepiphysiodesis treats the site

of deformity rather than inappropriate hindfoot surgery.

as you make the right diagnosis and don’t treat it. First, make certain

there is normal ankle dorsiflexion; if not, it is not metatarsus adductus (MTA), and may be a clubfoot. Look at the hindfoot; if there is significant valgus, think of a skewfoot (Fig. 25-10).

It may be difficult to differentiate between MTA and skewfoot with

radiographs in infants as the navicular is not yet ossified (Fig. 25-11). MTA may also be confused with a metatarsal longitudinal epiphyseal bracket (Fig. 25-12).

|

|

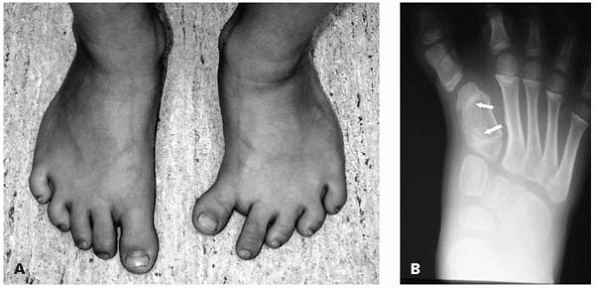

▪ FIGURE 25-10 (A) At first glance, this child may appear to have severe metatarsus adductus. (B)

When viewed from behind, the significant heel valgus (which does not correct when standing on his toes) suggests something other than metatarsus adductus. This child has a skewfoot. |

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-11 (A) AP radiograph of a 1-year-old. Is this metatarsus adductus? (B) AP radiograph of the same foot, at age 4 years. Note that the navicular is now ossified (arrow)

and can be appreciated in its position far lateral to the center of the talar head, making the diagnosis of skewfoot easier to appreciate. |

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-12 (A)

This child has a metatarsal bracket of the left foot. An increased space between the first and second toes is a clue that this foot has something other than metatarsus adductus. (B) AP radiograph demonstrating the longitudinal epiphyseal bracket (arrows) of the first metatarsus in this child. |

needed for MTA, do not do a capsular release as this leads to poor

results. We recommend an osteotomy of the medial cuneiform, rather than

the first metatarsal, both to avoid the proximal physis of the first

metatarsal, and for better correction. Lateral osteotomies may be of

the second to fifth metatarsals or the cuboid.

underlying neurologic condition. It has been reported that two thirds

of patients with painful high arches have an underlying neurologic

problem that turns out to be Charcot-Marie-Tooth about 50% of the time.23

If there are bilateral cavus feet, think of neuromuscular disease. If

the occurrence is unilateral, think of a spinal problem and order an

MRI of the entire spine. As a spine examination is not complete without

inspection of the feet, examination of a child with a cavus foot is not

complete without inspection of the spine. If the underlying

neuromuscular problem is treatable, get on with it before treating the

foot. Treatment for progressive cavus deformity with pain and

instability is surgical. Make certain the parents understand that the

foot deformity is not the problem, but is the result of the problem. It

is possible that future surgery will be needed, as the underlying

disease progresses in many cases.

associated with underlying neuromuscular conditions or syndromes. The

surgeon’s first job is to identify those other conditions.

obvious as some other foot deformities. A prominent talar head in the

setting of a rigid foot is suspicious, but avoid confusing an oblique

talus, positional calcaneovalgus, posteromedial bowing of the tibia, or

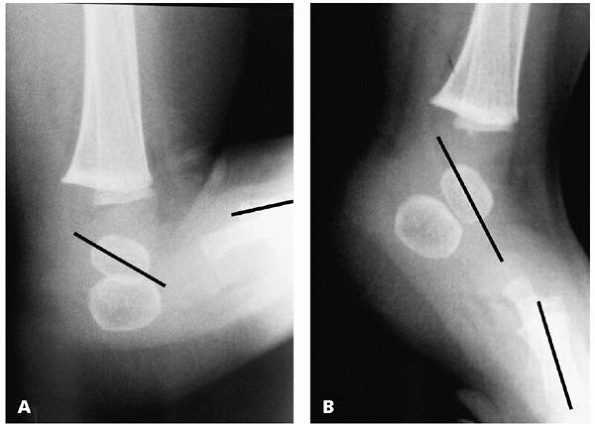

just a really flat foot, with a vertical talus (Fig. 25-13A).

By definition, a vertical talus is a fixed dorsal dislocation of the

navicular on the head of the talus. As the navicular is not ossified

until about age 3 years, and cannot be seen on plain radiographs, we

rely on the relationship of the axis of the talus and the first

metatarsal. The diagnosis is confirmed on the plantar flexed lateral

radiograph by observing that the axis of the talus passes plantar to

that of the first metatarsal (Figs. 25-13B and C).

Avoid the pitfall of believing that if the two axes become parallel,

there is not a vertical talus. Dorsal translation of the first

metatarsal axis in relation to that of the talus indicates dorsal

dislocation at the talonavicular joint (Fig. 25-14). The axis of the talus remains vertically aligned with the axis of the tibia on the dorsiflexion lateral radiograph.

|

|

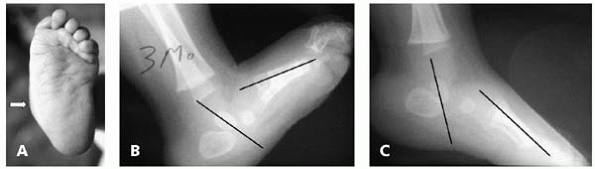

▪ FIGURE 25-13 Three-month-old with vertical talus. (A) Rocker bottom medial prominence characteristic of vertical talus. (B)

Lateral radiograph of foot is nondiagnostic. Although the axis of the talus is plantar to that of the first metatarsal, this radiograph is consistent with an oblique talus as well as vertical talus. (C) A forced plantarflexion lateral radiograph confirms the diagnosis of vertical talus as the axis of the talus and first metatarsal still do not line up, and the talus remains quite vertical relative to the first metatarsal. |

unlikely to correct the vertical talus deformity, though Dr. Matthew

Dobbs in St. Louis has reported some success.

Preoperative plantar flexion casting will stretch the dorsal skin and tendons, thus facilitating surgical deformity correction.

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-14 Example of a child with vertical talus (A) in which the axes of the talus and first metatarsal become nearly parallel in plantar flexion (B),

but the axis of the first metatarsal is translated dorsal to that of the talus. Recall that the definition of a vertical talus is a fixed, dorsal dislocation of the navicular relative to the talus to help understand why this radiograph is consistent with a vertical talus. |

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-15 (A)

Child with an oblique talus. Note that this radiograph shows a quite similar relationship between the talus and first metatarsal as that seen in Fig. 25-14. (B) With plantar flexion, the axis of the talus and first metatarsal significantly change their relationship. |

bunion surgery in adolescents than in adults. Stay out of trouble by

delaying surgery until skeletal maturity, if possible. If surgery is

needed, consider an opening wedge osteotomy of the medial cuneiform, if

the intermetatarsal angle is greater than 8 degrees. This will help

correct a medially deviated cuneiform-first metatarsal joint, as well

as avoid potential damage to the first metatarsal growth plate.

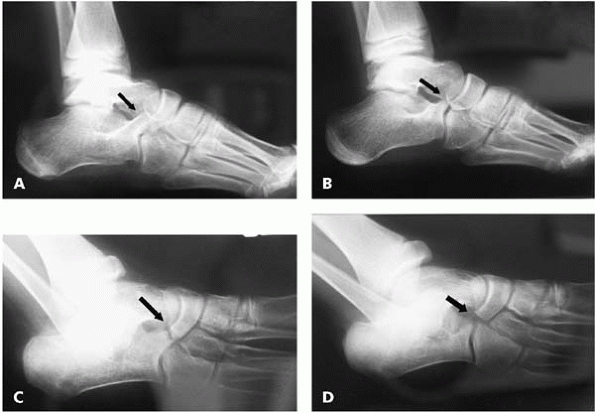

diagnosis of a tarsal coalition should be strongly suspected from the

physical examination, based on decreased subtalar joint motion and

inability to voluntarily invert the foot (see Fig. 25-3). Many children with a tarsal coalition present with rigid heel valgus and tightness of the peroneal tendons (Fig. 25-16).

clearly demonstrate tarsal coalitions, but they do provide lots of

clues. Oblique views are usually diagnostic of a calcaneonavicular

coalition, (Fig. 25-17) though a fibrous

coalition is best visualized on an MRI. A talocalcaneal coalition may

be seen on a Harris view if you are lucky enough to get a perfect shot,

but is most reliably seen on a CT scan (Figs. 25-17 and 25-18).

A recent series of 48 patients found the C-sign of Lateur on the

lateral radiograph to be present in all patients with flatfeet, but

present in only 40% of those with tarsal coalitions,24 (Fig. 25-18)

so an absence of the C-sign does not rule out a tarsal coalition. A CT

scan should be considered for all feet in which a calcaneonavicular

coalition has been identified on plain radiographs because of the

possibility of a coincidental talocalcaneal coalition in the same foot.

A second coalition was identified in 20% of patients undergoing CT

scans for tarsal coalition at the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital, though

this population from a tertiary pediatric center may be skewed towards

more severe cases.25

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-16

Photo of one of the authors sitting next to a patient with frequent recurrent ankle sprains. Both are trying to invert their feet, but the patient cannot due to bilateral tarsal coalitions. |

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-17 (A)

On a lateral radiograph of the foot, a calcaneonavicular coalition is difficult to identify conclusively. The arrow points to an elongated anterior process of the calcaneus (“anteater” sign), which is suggestive of a calcaneonavicular coalition. (B) The contralateral normal foot for comparison. (C) An oblique view clearly demonstrates the calcaneonavicular bar (arrow). (D) The contralateral normal foot for comparison demonstrates no coalition (arrow). |

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-18 Talar calcaneal bar is difficult to appreciate on plain radiographs, however talar beaking (white arrow) and the C-sign (black arrows) suggest this coalition may be present.

|

coalitions are asymptomatic, so the second pitfall here is in treating

something that doesn’t need treatment. Pain onset is usually between

ages 8 and 16 years in those who become symptomatic. The exact site(s)

and source(s) of pain in tarsal coalitions are not well established. A

few weeks of immobilization in a cast or walking boot may get a child

through a symptomatic period, and save the child from surgery.

Unfortunately, it is our experience that in most children who present

with painful tarsal coalitions, pain will return after immobilization,

and surgery is likely eventually.

exist in the foot and have a plan for your approach to each. Recurrent

discomfort occurs at times due to inadequate resection, particularly of

the talocalcaneal coalitions. Make certain that adequate bone is

removed at the primary surgery so that normal cartilage and joint is

seen at the periphery of the resection, and full inversion of the heel

does not cause impingement at the region of resection. Last, but not

least, as with any operation to treat pain in the feet, make the

patient and family aware that pain relief cannot be guaranteed.

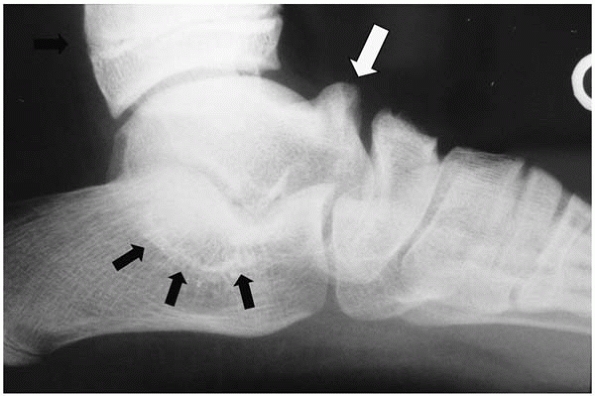

the appearance of the foot may be striking, spontaneous correction is

the rule (Fig. 25-19). Having the parents

perform stretching exercises may help the babies, and will keep the

parents happy that something is being done. The thing to watch out for,

on tests more than in real life, is the true diagnosis of posterior

medial bowing of the tibia, which usually corrects spontaneously but

may result in a 3- to 4-cm leg length discrepancy. See Chapter 10 on newborns for more discussion of this subject.

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-19 Calcaneal valgus in a newborn. It is not unusual for the dorsum of the foot to be touching the leg anterior to the tibia.

|

and do not confuse it with infection, fracture, or something more

serious. Do not treat if there are no symptoms, but immobilization for

a few weeks should help relieve discomfort.

Multiple ossification centers of the navicular may be confused with Köhler disease (Fig. 25-20).

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-20 Lateral view of a child with foot pain demonstrates Köhler disease. Arrow points to collapsed, avascular navicular.

|

although it can be associated with Ellis-Van Creveld syndrome, Down

syndrome and tibial hemimelia. Thus you should be on the lookout for

underlying disorders when encountering polydactyly.

longitudinal deficiency, most commonly fibular hemimelia, and may be

associated with other conditions such as a leg length discrepancy, ball

and socket ankle, or absent ACL.

|

|

▪ FIGURE 25-21 (A)

AP radiograph of a foot with preaxial duplication in a 1-month-old. The abnormally shaped first MT is characteristic of a longitudinal epiphyseal bracket. (B) An MRI of the same foot at age 7 months demonstrates the cartilage (black arrows) wrapping around the first MT, confirming the diagnosis or a longitudinal epiphyseal bracket. The proximal phalange of each of the two great toes is shown by white arrows. |

made much worse with surgery. Excessive scarring and unhappiness with

cosmetic appearance is not uncommon following surgical resection. But

don’t worry, plastic surgeons don’t read this book, so you may refer

patients who demand surgery to them.

-

Curly toes: almost

everyone has them at birth. Very rarely a 3- to 4-year-old will have

pain if the distal phalanx of the curly toe remains completely under

the adjacent toe. Tenotomy of the flexor digatorum longus of that toe

is usually curative. -

Congenital

overriding fifth toe: only about 50% will be painful in older children

and adults. Wait for symptoms. This is not just a tight extensor

tendon. It is a dorsomedial translation of the toe. Although the Butler

procedure has been shown to effectively correct the deformity, the

procedure is associated with risk to the vascularity of the toe. -

Flatfeet

-

Coalitions

-

Accessory navicular

-

Köhler disease

-

Flatfoot: really coalition or vertical talus in infant

-

MTA: really metaphyseal bar—needs surgery

-

Valgus foot: really fibular hemimelia

-

Fifth MT apophysis vs. fracture

-

Cavus foot: underlying neurologic problem if bilateral, spine problem if unilateral

-

Vertical talus: syndromes

-

Clubfoot

-

Flatfoot is a normal variant. An asymptomatic, isolated flatfoot does not require treatment.

-

Perform fusions of the foot only as an absolute last resort.

-

For the Ponseti

clubfoot method, long leg casts are essential, and results are

dependent on parental follow-through with bracing. -

For a cavus foot, look for an underlying neurologic condition.

-

For a vertical talus, look for an underlying neurologic condition or syndrome.

-

For a tarsal coalition, consider a CT to look for a second coalition.

DR, Mauldin D, Speck G, et al. Corrective shoes and inserts as

treatment for flexible flatfoot in infants and children [see comment]. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(6):800-810.

VS. Calcaneal lengthening for valgus deformity of the hindfoot: results

in children who had severe, symptomatic flatfoot and skewfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(4):500-512.

DE, Davids JR, Pugh LI. Clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of the

hip: value of screening hip radiographs in children with clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(4):503-507.

JA, Dolan LA, Dietz FR, et al. Radial reduction in the rate of

extensive corrective surgery for clubfoot using the Ponseti method. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):376-380.

MB, Gordon JE, Walton T, et al. Bleeding complications following

percutaneous tendoachilles tenotomy in the treatment of clubfoot

deformity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(4):353-357.

MB, Rudzki JR, Purcell DB, et al. Factors predictive of outcome after

use of the Ponseti method for the treatment of idiopathic clubfeet. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86A(1):22-27.

DA, Albanese EL, Levinsohn EM, Hootnick DR, et al. Pulsed color-flow

Doppler analysis of arterial deficiency in idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23(1):84-87.