CHAPTER 36 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 36 – Arthroscopic Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis

Anthony A. Romeo, MD,

Brian J. Cole, MD, MBA

Lateral epicondylitis is a well-known musculoskeletal phenomenon that can occur after minor trauma or chronic overuse. In general, lateral epicondylitis responds well to nonoperative management, including activity modification, counterforce bracing, physical therapy, and corticosteroid injections. A relatively small number of patients, however, present with refractory symptoms. In those cases, an operative procedure may be warranted. Many different operative techniques have been developed for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. The goal of this chapter is to describe a more recent technique—arthroscopic extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) release. We believe that this technique is advantageous because it offers direct visualization of the pathologic process, enables the surgeon to concomitantly address intraarticular disease, and is minimally invasive in nature and thus well tolerated by the patient.

Factors Affecting Surgical Indication

| • | Range of motion: should be normal | |

| • | Clicking with range of motion (synovial plica) | |

| • | Effusion (intraarticular disease) |

Factors Affecting Surgical Planning

| • | Previous ulnar nerve transposition | |

| • | Ulnohumeral or radiocapitellar arthritis | |

| • | Previous distal humerus or olecranon fracture |

It is important to perform a thorough neurovascular examination to rule out entrapment of the posterior interosseous nerve, subluxation of the ulnar nerve, or degenerative changes in the radiocapitellar joint.

| • | Anteroposterior view of the elbow in full extension | |

| • | Lateral view of the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion Optionally: |

|

| • | Axial view to outline the olecranon and its articulations | |

| • | Radial head view |

| • | Magnetic resonance imaging with or without the administration of gadolinium |

Magnetic resonance imaging will demonstrate degenerative changes in the origin of the ECRB; it may show a synovial plica in the radiocapitellar joint when it is performed with the administration of contrast material. Visualization of loose bodies is generally better with magnetic resonance images than with plain radiographs, which will display loose bodies in only 25% of the cases.

Indications and Contraindications

The ideal patient has localized symptoms directly anterior and inferior to the lateral epicondyle at the origin of the ECRB and has full range of motion. Conservative treatment options have failed.

Contraindications are those generally associated with elbow arthroscopy. These include significant alterations of the normal bone anatomy, previous placement of hardware, ankylosis of the elbow joint, acute or chronic soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis of the elbow.

The patient is placed in either the supine or prone position, according to the surgeon’s preference for elbow arthroscopy (we prefer the prone position). The procedure can be performed under general anesthesia or regional block with simple sedation. However, some patients may not tolerate the prone position under sedation alone because of unrelated issues, such as shoulder pain in the ipsilateral or contralateral shoulder.

The patient is positioned prone with the arm hanging over the side in 90 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation (

Fig. 36-1

). Care needs to be taken that the arm is not abducted more than 90 degrees and that the shoulder is not hyperextended to minimize the risk of neurovascular complications. A nonsterile tourniquet is used with inflation pressures between 200 and 250 mm Hg according to the size of the arm and systolic blood pressure. The procedure can be performed with the surgeon either standing or seated, and the operating table is adjusted accordingly.

|

|

|

|

Figure 36-1 |

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

| • | Tip of olecranon process | |

| • | Lateral epicondyle | |

| • | Medial epicondyle | |

| • | Ulnar nerve (test for subluxation) | |

| • | Radial head and radiocapitellar joint |

| • | Proximal medial portal: ulnar nerve | |

| • | Proximal lateral portal: lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve | |

| • | Excessive release: lateral ulnar collateral ligament, posterior interosseous nerve |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

Examination under anesthesia should evaluate range of motion and ligamentous stability. Diagnostic arthroscopy is useful to evaluate other intraarticular disease, such as loose bodies, ligamentous deficiency, or chondral defects.

Specific Steps (

Box 36-1

)

Before any portals are placed, a thorough manual palpation of the olecranon tip, the radiocapitellar joint, the lateral medial epicondyle, and the ulnar nerve is performed. Particular attention is needed to determine whether the patient has ulnar nerve subluxation. The landmarks are marked clearly (

Fig. 36-2

). A sterile or nonsterile tourniquet is necessary and should be inflated before any portals are placed.

| Surgical Steps | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 36-2 |

Then 30 mL of saline solution is instilled into the soft spot of the triangle formed between the tip of the olecranon, the lateral epicondyle, and the radial head. Visible distention of the joint and backflow through the injection needle (18-gauge) confirm intraarticular instillation.

To establish the proximal medial viewing portal, the medial epicondyle and the medial intermuscular septum are directly palpated. At approximately 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 1 cm anterior to the medial intermuscular septum, a small skin incision is made with a No. 15 blade. A small hemostat is used to spread carefully down to the capsule, thus avoiding injury to the cutaneous sensory nerves. With the elbow maintained in 90 degrees of flexion and neutral rotation, the cannula with a blunt trocar is then introduced by sliding along the anterior surface of the distal humerus, aiming toward the radiocapitellar joint. Subsequently, the proximal lateral portal is established approximately 2 cm proximal and 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle. The correct position of the portal is verified under direct vision by use of a spinal needle. Once the position is verified, the “nick and spread” technique is again used, and a blunt Wissinger rod is positioned to serve as a guide for a small 5-mm threaded arthroscopic cannula. An additional superior lateral portal can be helpful if the anterior capsule is capacious. A small key elevator can be inserted through this accessory portal and used to elevate the anterolateral capsule, greatly enhancing visualization from the medial portal.

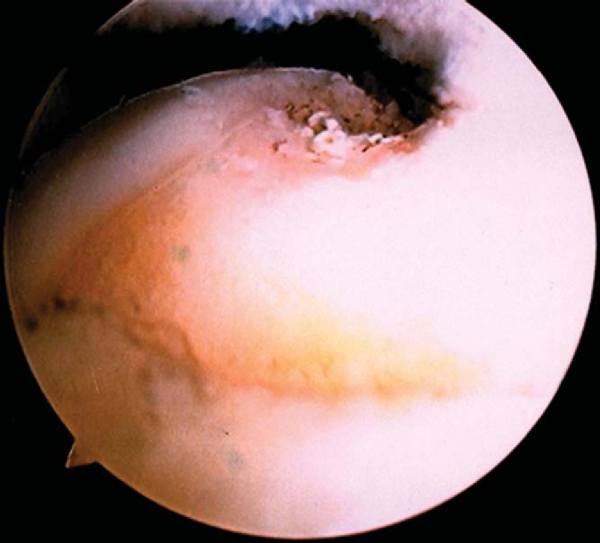

A routine diagnostic arthroscopy is performed. If any pathologic process is suspected in the ulnohumeral joint, a posterior portal is established to evaluate the ulnar and radial recesses. The radiocapitellar joint is evaluated for, among other entities, a soft tissue band or plica overriding the radius with pronation and supination, because this can be a cause of impingement. The lateral joint capsule and the insertion of the ECRB are assessed under direct vision. We prefer to grade ECRB involvement according to the grading suggested by Baker et al.[1]

3. Débridement of ECRB Origin and Release of ECRB

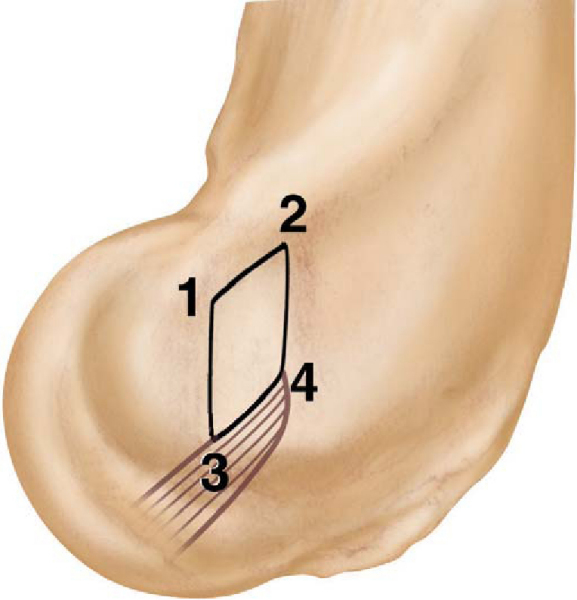

A thorough appreciation of the anatomy of the elbow, and of the ECRB in particular, is paramount to mastering this arthroscopic technique. The ECRB origin is extra-articular, thus requiring the resection of the capsule adjacent to the capitellum to visualize the ECRB origin. We prefer to perform the resection sequentially in four steps, resulting in a diamond-shaped resection zone (

Fig. 36-3

|

|

|

|

Figure 36-3 |

Step1: To visualize the ECRB, the overlying anterolateral capsule has to be removed, although in some patients, the capsule will already be torn, revealing the origin. The margins of the resection extend superiorly from the top of the capitellum to distally at the level of the midline of the radiocapitellar joint. If the resection extends farther distal than the midline of the radiocapitellar joint, the lateral collateral ligament is at risk.

Step 2: After adequate exposure has been obtained, we now turn our attention to resection of the ECRB origin. We start at the superior aspect of the capitellum, which represents the proximal and anterior margin of the resection. In a probing motion using a monopolar or bipolar radiofrequency probe, we resect the tendinous bands that represent the ECRB origin until we expose the red muscle fibers of the extensor carpi radialis longus.

Step 3: We then continue the resection anteroinferiorly. The posteroinferior border of the resection is marked by the lateral collateral ligament. One has to be careful to visualize the lateral collateral ligament. This is often easier once the semicircular fibers that cross from the lateral collateral to the annular radial ligament are visualized. Gravity inflow or the pump pressure can help with joint distention that separates the tendon from the lateral collateral ligament. The resection is performed under direct vision with the scope in the anteromedial portal (

Fig. 36-4

).

Step 4: The posterior aspect of the diamond-shaped resection zone is formed by the tendon of the extensor digitorum communis. The resection is carried up to the extensor digitorum communis tendon but not past it. There is a distinct fibrous band curving over top of the ECRB that constitutes the extensor aponeurosis. This band must not be cut because this could result in a subcutaneous fistula. The final portion of this step includes a decortication of the diamond-shaped débridement zone to create a biologic healing response. The capsule is not repaired.

Standard closure of the portals is performed.

Complications are those of elbow arthroscopy:

| • | Ulnar or lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve damage due to portal placement | |

| • | Posterior interosseous nerve or collateral ligament damage due to excessive release | |

| • | Infection | |

| • | Synovial fistula |

After débridement for lateral epicondylitis, good to excellent results are achieved in 85% to 90% of cases. The results of arthroscopic débridement are certainly comparable, and the arthroscopic approach has the additional benefit of being able to address concomitant disease that does exist in approximately 30% of cases. [1] [3] [4] Patients often are immediately pain free and can return to work between 1 and 3 weeks, depending on their physical category of work (

Table 36-1

).

| Author | Followup | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Baker et al[1] (2000) | 2.8 years | 42 patients |

| VAS: 0.9/10 for pain | ||

| Grip strength: 96% | ||

| Return to work at 2.2 weeks | ||

| Peart et al[6] (2004) | 2 years | 33 patients treated arthroscopically |

| 72% good and excellent results compared with 69% by open treatment | ||

| Earlier return to work for arthroscopically treated patients | ||

| Owens et al[5] (2001) | 2 years | 16 patients |

| VAS: 0.59/10 for pain | ||

| Average return to work at 6 days |

1.

Baker Jr CL, Murphy KP, Gottlob CA, Curd DT: Arthroscopic classification and treatment of lateral epicondylitis: two-year clinical results.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9:475-482.

2.

Cohen M, Romeo AA: Lateral epicondylitis: open and arthroscopic treatment.

J Am Soc Surg Hand 2001; 3:172-176.

3.

Kuklo TR, Taylor KF, Murphy KP, et al: Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis: a cadaveric model.

Arthroscopy 1999; 15:259-264.

4.

Mullett H, Sprague M, Brown G, Hausman M: Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: clinical and cadaveric studies.

Clin Orthop 2005; 439:123-128.

5.

Owens BD, Murphy KP, Kuklo TR: Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis.

Arthroscopy 2001; 17:582-587.

6.

Peart RE, Strickler SS, Schweitzer Jr KM: Lateral epicondylitis: a comparative study of open and arthroscopic lateral release.

Am J Orthop 2004; 33:565-567.

7.

Romeo AA, Fox JA: Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis—the 4-step technique.

Available at: www.orthopedictechreview.com/issues/sepoct02/pg26.htm![]()