Infection

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Cramer, Kathryn E.; Scherl, Susan A.

Title: Pediatrics, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section II: – Emergency Department > 17 – Infection

17

Infection

Jon R. Shereck

Richard M. Schwend

Musculoskeletal infections in children are common

conditions likely to be encountered by all orthopaedic surgeons. The

diagnosis of bone or joint sepsis is often difficult to make. The child

can present with many different signs and symptoms (Box 17-1), and there are multiple conditions that can mimic infection (Box 17-2).

Although evaluation and treatment of orthopaedic infections is

sometimes controversial, by following basic principles, significant

sequela can be prevented.

conditions likely to be encountered by all orthopaedic surgeons. The

diagnosis of bone or joint sepsis is often difficult to make. The child

can present with many different signs and symptoms (Box 17-1), and there are multiple conditions that can mimic infection (Box 17-2).

Although evaluation and treatment of orthopaedic infections is

sometimes controversial, by following basic principles, significant

sequela can be prevented.

ACUTE HEMATOGENOUS OSTEOMYELITIS

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

-

Staphylococcus aureus (most common)

-

Group A Streptococcus

-

Streptococcus pneumoniae

-

Group B β-hemolytic Streptococcus (usually in neonates)

BOX 17-1 MANIFESTATIONS OF ORTHOPAEDIC INFECTIONS IN CHILDREN

-

Malaise

-

Irritablility

-

Fever

-

Pain

-

Pseudoparalysis

-

Tenderness

-

Limp

-

Refusal to walk

-

Stiff joint

-

Joint effusion, if superficial joint

-

Asymmetric positioning

-

Erythema

-

Swelling

-

Warmth

Epidemiology

-

Half of affected children are younger than 5 years of age, one-third are younger than 2 years of age.

-

Male-to-female ratio is up to 4 to 1.

-

Common in warmer climates; peak incidence in late summer or early fall

-

Most common in metaphyseal region of

lower extremity long bones. Seen in locations with the fastest growth

rate, such as distal femur

Pathophysiology

-

Trauma to the metaphysis and bacteremia have a combined role in initiating osteomyelitis.

-

Blood-borne bacteria are deposited in metaphyseal venous sinusoids.

-

Medullary vessels thrombose.

-

This inhibits access of inflammatory cells for proper immune response.

-

Purulent material is produced. Infection

spreads through Volkmann canals or the haversian bone system.

Subperiosteal abscess may form. -

Due to the compromised vascularity of

cortical bone, a sequestrum (loosely adherent piece of dead bone) may

develop. An involucrum (new bone) may form over the sequestrum. Poor

vascularity may lead to chronic osteomyelitis. -

Joints where the metaphysis lies within the capsule are at particular risk for septic arthritis:

-

□ Proximal femur and hip

-

□ Proximal humerus and glenohumeral joint

-

□ Lateral distal tibia and ankle

-

□ Radial neck in the elbow

-

BOX 17-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ORTHOPAEDIC INFECTIONS

Osteomyelitis

-

Transient synovitis

-

Soft tissue abscess

-

Cellulitis

-

Pyogenic arthritis

-

Fracture

-

Thrombophlebitis

-

Rheumatic fever

-

Bone infarction

-

Gaucher disease

-

Malignancy

-

Osteosarcoma

-

Ewing sarcoma

-

Leukemia

-

Neuroblastoma

-

Wilms tumor

-

Septic Arthritis

-

Transient synovitis

-

Rheumatic fever

-

Leukemia

-

Cellulitis

-

Juvenile arthritis

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Hemophilia

-

Lyme arthritis

-

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

-

Hemiarthrosis

-

Viral or reactive arthritis

-

Chondrolysis

-

Sickle cell crisis

-

Lillonodular synovitis

-

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

-

Slipped capital femoral ephiphysis

P.190

DIAGNOSIS

Criteria for diagnosing osteomyelitis are outlined in Boxes 17-3 and 17-4.

History

-

History of recent or concurrent infection in about 50% of patients

-

Preceding trauma in up to 50%

-

Duration of symptoms typically less than 2 weeks

-

Continuous bone pain for at least 24 hours

Physical Examination

-

Local signs of erythema, swelling, and

warmth are seen with advanced infection. If cellulitis is present, this

may indicate an underlying abscess. -

Pain is not well localized if the infection involves the spine or pelvis

-

Signs are different for different ages.

-

□ Neonates: swelling at the affected site

due to an easily penetrated thin periosteum. However, the only finding

may be a systemically ill neonate, or one who is irritable and failing

to thrive. -

□ Toddler and young children: pain,

usually point tenderness, is seen in 50%. A limp or inability to bear

weight is commonly seen with infections of the lower extremity. -

□ Adolescents: may be more locally tender because of more resilient and tense tissues.

-

BOX 17-3 MORREY AND PETERSON CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF OSTEOMYELITIS

Definite: The pathogen is isolated from the bone or adjacent soft tissue, or there is histologic evidence of osteomyelitis.

Probable: A blood culture is positive in the setting of clinical and radiographic features of osteomyelitis.

Likely: Typical clinical

findings and definite radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis are

present, and there is a response to antibiotic therapy.

findings and definite radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis are

present, and there is a response to antibiotic therapy.

Adapted from Morrey BF, Peterson HA. Hematogenous pyogenic osteomyelitis in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1975;6:935-951.

BOX 17-4 PELTOLA AND VAHVANEN CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF OSTEOMYELITIS

The diagnosis is established when two of the following four criteria are met:

-

Pus is aspirated from bone.

-

A bone or blood culture is positive.

-

The classic symptoms of localized pain, swelling, warmth, and limited range of motion of the adjacent joint are present.

-

Radiographic features characteristic of osteomyelitis are present.

Adapted from Peltola H, Vahvanen V. A comparative study

of osteomyelitis and purulent arthritis with special reference to

aetiology and recovery. Infection 1984;12:75-79.

of osteomyelitis and purulent arthritis with special reference to

aetiology and recovery. Infection 1984;12:75-79.

Laboratory Features

-

White blood cell (WBC) count may be normal in up to 70% of patients.

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR):

-

□ Elevated in more than 90% of patients, but is nonspecific.

-

□ Levels rise slowly and peak in 3 to 5

days, so may be normal if child presents early in the course of the

infection. The neonate, patient with sickle cell disease, or the child

who is taking steroids may not have an elevated ESR.

-

-

C-reactive protein (CRP):

-

□ Acute phase protein synthesized by the liver.

-

□ Elevated in as many as 97% of patients.

-

□ Levels rise rapidly and peak in 2 days. CRP is quick to decline (within 6 hours) after initiation of appropriate therapy.

-

-

Blood cultures are positive in 30% to 60% of patients.

-

Cultures taken from involved bone:

-

□ Have a higher yield of pathogens (positive in up to 75% of patients) and may be the only positive culture site in 28%.

-

□ Gram stain should be performed at same time.

-

□ Consider fine-needle biopsy to obtain material for histologic examination.

-

-

Surgical biopsy should be sent for histopathology when débridement is clinically indicated.

Radiologic Features

-

Plain radiographs

-

□ Do not accept incomplete or poor quality films. Need two orthogonal views of the involved area.

-

□ Comparison views of the contralateral extremity may be helpful.

-

□ Periosteal new bone formation may be evident by 5 to 7 days.

-

□ Osteolytic changes require bone mineral loss of 30% to 50%. May not be apparent until 10 to 14 days after onset.

-

-

Technetium-99m bone scintigraphy

-

□ Useful if of normal radiographs but still clinical suspicion of osteomyelitis.

-

□ Sensitivity: 84% to 100%. Specificity: 70% to 96%. Sensitivity is decreased in the neonate.

-

□ Prior aspiration does not give false-positive results.

-

□ “Cold” scans in late stages of infection.

-

□ Very worrisome for a severe infection or osteonecrosis.

-

□ Decreased uptake due to relative

ischemia caused by increased pressure from purulent material: leads to

vascular congestion and osteonecrosis -

□ Positive predictive value of up to 100%

-

-

-

Magnetic resonance imagine (MRI)

-

□ Sensitivity: 88% to 100%. Specificity: 75% to 100%

-

□ Very useful for suspected spinal and

pelvic infections. Consider using if patient has not responded after 2

days of antibiotic therapy -

□ Excellent imaging modality for planning surgical approaches

-

□ T1-weighted and short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) images are most useful for detection of acute osteomyelitis

-

-

Computed tomography (CT)

-

□ Most useful in detection of gas in soft tissue infections and in identification of sequestra in chronic osteomyelitis

-

-

Ultrasound

-

□ Detects fluid collections and soft tissue swelling

-

□ Advantages: low cost, relative availability, noninvasive, nonionizing radiation, no sedation required

-

□ Disadvantages: lack of specificity, operator dependent, inability to image marrow or show cortical detail

-

Diagnostic Workup

-

A complete and thorough history and physical examination is performed. Be anatomically specific about the location of the pain.

-

Laboratory and imaging studies as previously described

-

Once an anatomic source is localized,

aspiration is used to obtain the organism. Surgical biopsy can also be

used to obtain the organism. The decision to use surgery requires

clinical judgment. It usually is performed to drain pus, débride

necrotic tissue, or when the patient has not responded to appropriate

antibiotic therapy.

TREATMENT

Morrissey has advocated the following treatment principles for infection:

-

Find the organism, which can generally be identified in 50% to 70% of cases.

-

Use appropriate antibiotics.

-

Deliver the antibiotic to the area of infection.

-

Stop the tissue destruction: typically by surgical drainage and débridement.

-

Once the diagnosis has been made and

blood and tissue cultures obtained, begin empiric intravenous (i.v.)

antibiotics. Since most infections are caused by S. aureus, group A Streptococcus, or Pneumococcus, Cefazolin (Kefzol) 50 mg per kg per dose, every 8 hours, maximum dose 12 g per day is a safe and reasonable initial choice. -

Nafcillin or oxacillin are reasonable initial alternatives.

-

Consider the following special situations:

-

□ Neonates: add gentamicin or cefotaxime to the regimen.

-

□ Allergy to penicillin: cefazolin is the antibiotic of choice.

-

□ Allergy to both penicillin and cephalosporins: clindamycin or vancomycin.

-

□ Methicillin-resistant S. aureus is suspected: vancomycin.

-

□ Consider infectious disease consultation for these special situations.

-

-

Aspiration or biopsy is indicated if no improvement after 36 to 48 hours of appropriate i.v. antibiotics.

-

Switching to oral antibiotics: very

subjective and clinical judgment is required. The patient should appear

well, have a normal temperature and pulse, have a markedly improved

clinical examination, and be able to take oral medication. -

Intravenous antibiotics may be continued longer if:

-

□ Initiation of therapy is markedly delayed and necrotic tissue is suspected.

-

□ Poor response, or no response, after empiric i.v. therapy.

-

□ Patient is unable to take oral medications.

-

□ There is no effective oral antibiotic for the identified organism or if there is a very unusual organism.

-

-

Duration of therapy is determined by

clinical improvement. Traditionally, antibiotics are used for 4 to 6

weeks. Follow clinical response and ESR. -

Indications for surgical débridement

-

□ Evidence of an intraarticular, subperiosteal, intramedullary, or soft-tissue abscess

-

□ Sequestrum

-

□ Contiguous focus of infection

-

□ Poor response to appropriate i.v. antibiotics

-

-

Surgical management

-

□ Drain the soft tissue abscess

-

□ Incise the periosteum

-

□ Drill the cortex

-

□ Remove all dead bone

-

-

Postoperative immobilization in a splint or cast, especially if at risk for a pathologic fracture.

P.192

SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

-

Neonates: group B Streptococcus, S. aureus, Gram-negative bacilli

-

1 month to adolescent: S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes

-

Adolescents: may also see Neisseria gonorrheae

-

Haemophilus influenzae B rare unless child has not been immunized

Epidemiology

Septic Arthritis

-

Most common in children less than age 2 years of age

-

More common in boys than girls

Pathophysiology

-

Hematogenous seeding of bacteria in the

rich vascular network in the subsynovial layer is present, which then

progresses into the joint. -

Other possible routes for septic arthritis to develop:

-

□ Local spread from a contiguous infection, such as an intraarticular osteomyelitis.

-

□ Penetrating trauma or surgical infection.

-

□ Percutaneous fixation pins that are intraarticular, such as in the knee.

-

-

Acute inflammatory stage:

-

□ Polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) rapidly enter the joint space.

-

□ Plasma proteins cross the synovial membrane, resulting in a tense effusion.

-

□ Leading to significant pain even at rest

-

-

Articular cartilage can be destroyed in response to infection by two mechanisms:

-

□ Degradation by proteolytic enzymes (e.g., collagenase, proteinases).

-

□ Interleukin-1 from monocytes mediates the release of acid and neutral proteases by chondrocytes and synoviocytes.

-

-

Early diagnosis and treatment is

essential to limiting articular cartilage destruction. If treatment is

delayed beyond 4 days, articular damage can be permanent.

DIAGNOSIS (BOX 17-5)

History

-

May have a history of a recent upper

respiratory infection or local soft tissue infection, preceding trauma,

fever, malaise, and pain -

Pain at rest, limp, and limited spontaneous motion

-

Fever, which may not be present if small joint involved

-

Consider the possibility of an altered immune status.

Physical Examination

-

Patients may appear more ill compared with osteomyelitis.

-

Young children may be very irritable (see Box 17-1).

-

Pain is present at rest and is increased with passive joint motion and axial loading.

-

If the hip joint is involved, it is

typically held in external rotation, abduction, and mild flexion to

maximize the joint volume and decrease the resting pressure. -

The neonate may have mild or absent signs and symptoms.

-

When a septic hip is suspected, consider

adjacent sites as the primary cause of infection, including pelvic

abscess, infection of any of the muscles about the hip and pelvis,

pelvic osteomyelitis, or proximal femur osteomyelitis. The psoas sign

of pain on extension and internal rotation of the hip is present in as

many as 89% of patients with primary pyogenic psoas abscess.

Laboratory Features

-

WBC count elevated in 30% to 60% of patients

-

□ PMNs elevated in 60% to 80%

-

-

ESR elevated in more than 90% of

patients, but not elevated early in the course of the infection. It is

highly sensitive, but nonspecific. -

CRP

-

□ Helps detect associated septic arthritis in patients with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis

-

□ If CRP concentration by the third day

is 1.5 times the level on admission, there is a high likelihood that

associated septic arthritis is present.

-

-

Blood cultures are positive in 40% to 50%

of patients and are the only positive culture site in 12%. Up to 70%

yield if both blood and joint cultures obtained. -

A large-bore (20-gauge or larger) needle

aspiration should be obtained on all septic joints. There is little

risk of seeding a bone or joint in an area of cellulites.-

□ Hip joint aspiration: consider using

arthrographic or ultrasound guidance. Patient should be sedated or

under general anesthesia.

-

-

Synovial fluid analysis:

-

□ WBC greater than 50,000/mL with 90% PMNs is indicative of bacterial infection.

-

□ Glucose level: synovial fluid/serum glucose ratio of less than 0.5, or synovial fluid glucose 40 mg/dL less than serum level.

-

□ Positive mucin clot test: assesses

integrity of hyaluronic acid of joint fluid. Place a drop of glacial

acetic acid into the fluid while stirring with a glass rod. In the

presence of bacteria, the consistency of the fluid resembles that of

curdled milk due to degraded hyaluronic acid. -

□ Gram stain is positive in about 50% of cases.

-

-

A Mantoux skin test, or purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test should be placed if tuberculosis is a possibility.

Radiologic Features

-

Plain radiographs

-

□ Frequently normal

-

□ Changes are subtle and may include:P.193

-

□ Soft tissue edema, loss of tissue planes

-

□ Joint space widening is seen with capsular distention, especially in the infant hip joint

-

□ Subluxation or dislocation of the involved joint, particularly in the neonate

-

□ Epiphyseal ischemic necrosis

-

□ Associated metaphyseal or epiphyseal osteomyelitis

-

-

-

Bone scan

-

□ Rarely useful to diagnose septic

arthritis, but can be helpful when the exact location of the septic

joint is difficult to identify. -

□ A “cold bone scan” of the hip is particularly worrisome.

-

□ In a septic joint, the distribution of uptake is uniform within the joint capsule; asymmetric uptake indicates osteomyelitis.

-

-

MRI

-

□ Used in patients with septic hip

arthritis who have not responded to conventional therapy: useful in

delineating areas of residual infection and defining associated

osteomyelitis. -

□ Very helpful for imaging the pelvis if an abscess is suspected.

-

-

CT: no useful role in septic arthritis

-

Ultrasound

-

□ More sensitive (almost 100%) than plain

radiography in diagnosing an effusion. However, it is not specific in

determining whether the effusion is infectious. -

□ Very useful in evaluating suspected

sepsis of the hips. Both hips should be imaged along the axis of the

femoral neck. Affected hip will show asymmetry of the capsule-to-bone

distance of 2 mm or more, indicating an intraarticular effusion.

Echogenicity suggests a septic arthritis or clotted hemorrhagic

collections, but is not very specific. -

□ Results must be combined with clinical impression to determine need for hip aspiration.

-

□ Aspiration can be performed under guidance.

-

Diagnostic Workup

-

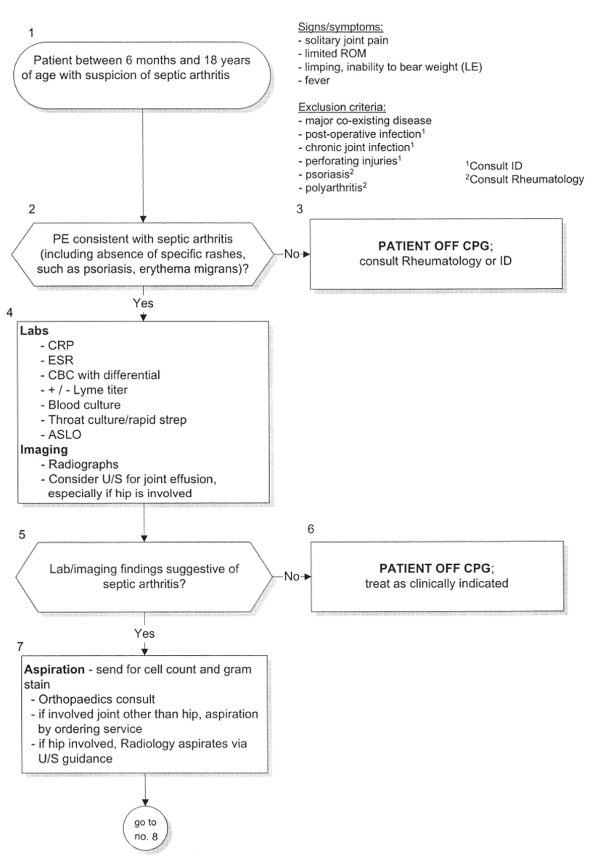

A septic hip arthritis clinical practice guideline (CPG) algorithm has been proposed by Kocher and colleagues (Algorithm 17-1). It includes a thorough diagnostic workup protocol as well as the appropriate treatment.

-

□ Compared with previous standard practice, use of this CPG has resulted in:

-

□ Less frequent use of bone scan (13% vs. 40%)

-

□ Earlier conversion to oral antibiotics (3.9 vs. 6.9 days)

-

□ Lower use of inappropriate surgical drainage (53% vs. 87%)

-

□ Lower rate of nonrecommended antibiotic course (7% vs. 93%).

-

□ Shorter hospital stay (4.8 vs. 8.3 days)

-

-

□ Despite less extensive diagnosis and treatment, there was no less successful clinical outcome with use of the CPG.

-

-

If clinical suspicion is high after a

thorough history and physical and is supported by initial lab values or

radiographs, then aspiration of the involved joint is used to confirm

the presence of infection.-

□ CRP, ESR, complete blood count (CBC)

with differential, Lyme titer, blood culture, throat culture/rapid

strep, anti-strepolysin (ASLO). -

□ Plain radiographs

-

□ If there is uncertainty about the

presence of a septic effusion about the hip after the initial

evaluation, ultrasonography is of diagnostic value to confirm the

presence of an effusion. Confirmed hip effusion with a clinical picture

suggestive of septic arthritis should receive diagnostic aspiration.

-

-

Septic arthritis can still be present despite negative cultures (Box 17-5).

BOX 17-5 MORREY AND PETERSON CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF SEPTIC ARTHRITIS IN PATIENTS WITH NEGATIVE CULTURES

The diagnosis is established when five of the following six criteria are present:

-

Temperature exceeds 38.3°C

-

Swelling of the suspected joint is present. This is not always obvious for a deep joint such as the hip

-

Pain that is exacerbated with movement

-

Systemic symptoms

-

No other pathologic processes are present

-

Satisfactory response to antibiotic therapy

-

Adapted from Morrey BF, Peterson HA. Hematogenous pyogenic osteomyelitis in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1975;6:935-951.

TREATMENT

-

Blood and joint cultures should be obtained prior to administration of antibiotics.

-

Open arthrotomy for patients with hip involvement.

-

Septic knee arthritis does well with arthroscopic lavage.

-

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be

initiated. Cefazolin (Kefzol) 50 mg/kg per dose, every 8 hours, maximum

dose 12 g/day. Nafcillin or oxacillin are reasonable initial

alternatives. -

Special situations are similar to those described for osteomyelitis. Ceftriaxone for possible H. influenzae B or N. gonorrhea infection.

-

Final antibiotic choice is directed by the culture and sensitivity results.

-

Duration of i.v. antibiotics is based on

the clinical response. The CPG typically averaged 4 days of i.v.

antibiotic before switching to an oral antibiotic. Serum bactericidal

levels are not routinely obtained. -

Total duration of antibiotics for septic arthritis is typically about 3 weeks. Follow clinical response and ESR.

P.194

|

|

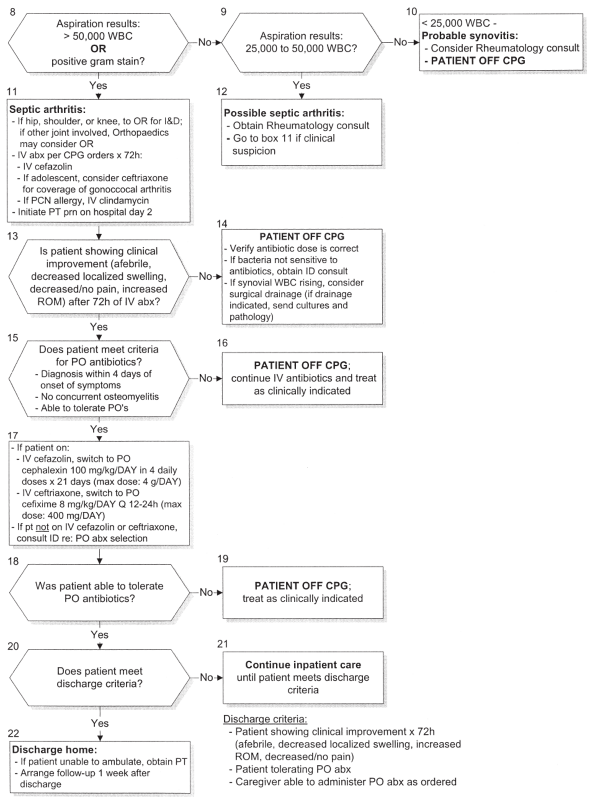

Algorithm 17-1 Septic arthritis clinical practice guideline algorithm. (Copyright © 2001 by Children’s Hospital, Boston.)

|

P.195

|

|

Algorithm 17-1 (continued)

|

P.196

SPECIAL SITUATIONS

SUBACUTE HEMATOGENOUS OSTEOMYELITIS

-

Slow, insidious onset. Commonly presents as a metaphyseal lesion such as a Brodie abscess or an epiphyseal lesion

-

Can mimic other lesions such as chondroblastoma, eosinophilic granuloma, osteoid osteoma, or osteoblastoma

-

Treat with i.v. antibiotics. Surgery if unresponsive.

CHRONIC RECURRENT MULTIFOCAL OSTEOMYELITIS

-

Inflammatory process of the bone with no clear etiology

-

Multiple lesions, normal WBC count. Nonspecific radiographs with poorly defined metaphyseal lesions

-

Symptoms resolve, then recur, and can continue to recur for several years.

-

Treat with nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs.

OSTEOMYELITIS AND SEPTIC HIP ARTHRITIS IN THE NEONATE

-

Group B Streptococcus most common; however, many different organisms can be involved.

-

Immature immune system. Infection can be

extensive with multiple sites. Symptoms are often mild or minimal. In

the septic newborn one should always suspect a bone or joint infection. -

Infections may be related to an indwelling i.v. catheter or may occur in the apparently healthy newborn after discharge.

-

The hip is very susceptible to infection,

ischemic necrosis, septic dislocation, and physeal injury. Aspiration

of a suspected hip infection should always be performed and surgery

provided whenever pus is found. -

Intravenous rather than oral antibiotics

TRANSIENT SYNOVITIS OF THE HIP

-

Must always be differentiated from septic arthritis of the hip

-

Considered to be an immune-mediated mechanism after a viral infection

-

Less signs of systemic illness or joint inflammation. More comfortable at rest

-

Kocher and colleagues looked at the following four predictors of septic arthritis versus transient synovitis:

-

□ History of fever

-

□ Non-weightbearing

-

□ ESR ≥40 mm/hour

-

□ WBC >12,000 cells/mm3

-

-

Probability of septic arthritis with positive predictors:

-

□ 1 of 4:2—5%

-

□ 2 of 4:33—62%

-

□ 3 of 4:93—97%

-

□ 4 of 4:99—99.8%

-

POSTGASTROENTERITIS ARTHRITIS

-

Joint involvement after infection with intestinal pathogens: Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter

-

Positive stool culture

REITER SYNDROME

-

Oral and genital lesions. May have eye symptoms

-

In the sexually active child, positive Gonococcus or Chlamydia cultures confirm the diagnosis.

SACROILIAC JOINT INFECTIONS

-

Pain in gluteal region, abdomen, or lumbar region

-

FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation) test positive on physical examination

-

Initially, radiographs are normal. MRI is

very useful in the pelvic region and can detect an adjacent soft tissue

abscess, particularly when the patient is not responding to antibiotic

treatment. -

Blood and stool cultures are obtained and are positive in 60%. Usually S. aureus, but can be caused by Salmonella.

-

Treatment: i.v. antibiotics to cover S. aureus

CULTURE-NEGATIVE AND GONOCOCCAL SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

-

Rash, tenosynovitis especially on the dorsum of the hands and polyarticular arthritis are suspicious findings for N. gonorrheae.

-

Culture all mucous membranes.

-

Report to protective services if N. gonorrheae infection is confirmed in a young child.

-

In future, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be useful for diagnosis.

-

Ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/day) is used for possible H. influenzae B or N. gonorrhea infection.

LYME ARTHRITIS

-

History of documented tick bite in known endemic area

-

Typical rash of erythema migrans

-

Obtain Lyme titer if diagnosis considered.

VIRAL ARTHRITIS

-

Multiple small joints

-

May mimic septic arthritis, especially if caused by parvovirus

P.197

TUBERCULOSIS

-

Bone or joint involvement is seen in 10% of tuberculosis cases.

-

Systemic symptoms, and mild pain are often seen.

-

The spine is the most common musculoskeletal site and is involved in 50%, with kyphosis the most common deformity.

-

PPD

-

Prolonged and monitored antimicrobial therapy is mainstay of treatment.

DISCITIS

-

The pediatric disc receives its blood

supply directly from the adjacent bone, which makes the disc

susceptible to hematogenous infection. -

Findings include fever, systemic illness,

refusal to walk, or abdominal pain in the younger child. Back pain,

night pain, and stiffness in flexion are more common in the older child. -

Blood cultures are positive in 50%, CRP is markedly elevated, and ESR is moderately elevated.

-

Plain radiographs show disc space

narrowing and occasionally end-plate changes. Bone scan is more

sensitive and can diagnose the infection about a week earlier than can

plain radiographs. -

Initially treat with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Casting or bracing is used for comfort.

SICKLE CELL DISEASE

-

Patients are at risk for osteomyelitis due to microvascular disease and bony infarcts.

-

Vasoocclusive pain crisis (infarction) more common than osteomyelitis. Symptoms resolve sooner.

-

Osteomyelitis produces high fever and an

ill patient. There is an elevated ESR and positive blood cultures.

Aspiration is the best diagnostic test to confirm infection. Surgical

drainage is usually necessary. -

S. aureus is still the most common organism in osteomyelitis in sicklers, but salmonella is more common in sicklers than in the general population.

PUNCTURE WOUNDS

-

Classically, a nail through a dirty, old athletic shoe

-

Small percentage develops osteomyelitis or septic arthritis by direct inoculation into the bone or joint. Typically caused by Pseudomonas.

-

Confirmed deep infection with Pseudomonas requires surgical débridement and i.v. antibiotic coverage.

PEARLS

-

Septic arthritis of the hip is a true surgical emergency, especially in the neonate.

-

Ultrasound of the hip is very sensitive to confirm an effusion, which then needs to be explained.

-

Beware of the “cold” bone scan: associated with worse prognosis and suggestive of ischemia.

-

Obtain infectious disease consultation for:

-

Unusual organism: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, gram-negative

-

Unusual host: sickle cell, immunocompromised, malabsorption

-

Unusual site: multiple joints, bones, or multiple organs

-

-

If patient unresponsive to antibiotic treatment consider:

-

Wrong diagnosis

-

Wrong antibiotic, dose, or route of administration

-

An abscess or undrained pus

-

Immune deficiency

-

-

Pus should be drained surgically when:

-

Purulence on aspiration

-

Radiographic evidence of purulence/abscess: hole in bone, fluid collection

-

Unresponsive to appropriate antibiotics

-

SUGGESTED READING

Herring, JA. Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopaedics, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002;1841-1877.

Kocher

MS, et al. Efficacy of a clinical practice guideline on process and

outcome for septic arthritis of the hip in children. Paper No. 74

presented at Annual Meeting POSNA; Salt Lake City; 2001.

MS, et al. Efficacy of a clinical practice guideline on process and

outcome for septic arthritis of the hip in children. Paper No. 74

presented at Annual Meeting POSNA; Salt Lake City; 2001.

Kocher

MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis

and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based

clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg (Am),

1999;81:1662-1670.

MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis

and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based

clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg (Am),

1999;81:1662-1670.

Morrey BF, Peterson HA. Hematogenous pyogenic osteomyelitis in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1975;6:935-951.

Morrissy

RT, Weinstein SL. Lovell and Winter’s pediatric orthopaedics, 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:459-505.

RT, Weinstein SL. Lovell and Winter’s pediatric orthopaedics, 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:459-505.

Peltola

H, Vahvanen V. A comparative study of osteomyelitis and purulent

arthritis with special reference to aetiology and recovery. Infection

1984;12:75-79.

H, Vahvanen V. A comparative study of osteomyelitis and purulent

arthritis with special reference to aetiology and recovery. Infection

1984;12:75-79.

Song KM, Sloboda JF. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:166-175.

Sponseller PD. Orthopaedic knowledge update: pediatrics 2. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2002:27-41.

Sucato DJ, Schwend RM, Gillespie R. Septic arthritis of the hip in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1997;5:249-260.