Compartment Syndrome

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Cramer, Kathryn E.; Scherl, Susan A.

Title: Pediatrics, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section II: – Emergency Department > 15 – Compartment Syndrome

15

Compartment Syndrome

Howard R. Epps

Compartment syndrome is a potentially devastating

condition that requires immediate attention. Elevated pressures, within

the confined compartments of a limb, cause permanent injury to muscle

and nerves. Early recognition and treatment can arrest the process

before irreversible damage occurs. Prompt detection and treatment can

result in excellent outcomes; delayed or missed diagnosis can cause

significant disability. The challenge remains to make an early

diagnosis, particularly in children.

condition that requires immediate attention. Elevated pressures, within

the confined compartments of a limb, cause permanent injury to muscle

and nerves. Early recognition and treatment can arrest the process

before irreversible damage occurs. Prompt detection and treatment can

result in excellent outcomes; delayed or missed diagnosis can cause

significant disability. The challenge remains to make an early

diagnosis, particularly in children.

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

Compartment syndrome results from intrinsic causes, extrinsic causes, or both (Box 15-1).

BOX 15-1 CAUSES OF COMPARTMENT SYNDROMES

Intrinsic Causes

-

Fracture (open or closed)

-

Crush injury

-

Vascular injury

-

Burns

-

Toxic venom

-

Viral illness

-

Intraosseous infusion

-

Venous or arterial access

-

Intramuscular hematoma

-

Hemophilia

-

Traction (skin or skeletal)

-

Intraoperative positioning (lithotomy)

-

Osteotomy or leg lengthening

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Prolonged tourniquet application

Extrinisic Causes

-

Compressive cast or bandages

-

Pneumatic antishock garment

-

Prolonged external pressure

-

Intrinsic factors increase the volume inside the limited space of a limb compartment, raising the internal pressure.

-

Extrinsic causes elevate the intracompartmental pressure by external compression.

Pathophysiology

Intrinsic or extrinsic factors initiate a series of events that eventually cause a compartment syndrome:

-

Bleeding within a compartment is a common

etiology, but increased vascular permeability, or transient ischemia

followed by reperfusion and cellular edema are commonly implicated as

well. -

The insult raises the pressure inside the compartment.

-

Once the pressure rises above venous pressure, outflow is obstructed.

-

Decreased venous outflow, in turn, causes intracompartmental congestion and further elevation of tissue pressure.

-

The pressure eventually exceeds arteriolar and capillary pressure, causing ischemia.

-

Cellular swelling from ischemia further increases the volume and pressure within the compartment.

-

Without decompression, the ischemia eventually causes irreversible damage to muscles and nerves.

DIAGNOSIS

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. A high

index of suspicion is critical, particularly in children. While

compartment pressure measurement provides valuable information, when

possible one should rely primarily on the clinical examination.

index of suspicion is critical, particularly in children. While

compartment pressure measurement provides valuable information, when

possible one should rely primarily on the clinical examination.

Physical Examination and History

Clinical Features

The clinical signs of a compartment syndrome result from

the effects of increased pressure and subsequent ischemia. The primary

features include:

the effects of increased pressure and subsequent ischemia. The primary

features include:

P.181

|

|

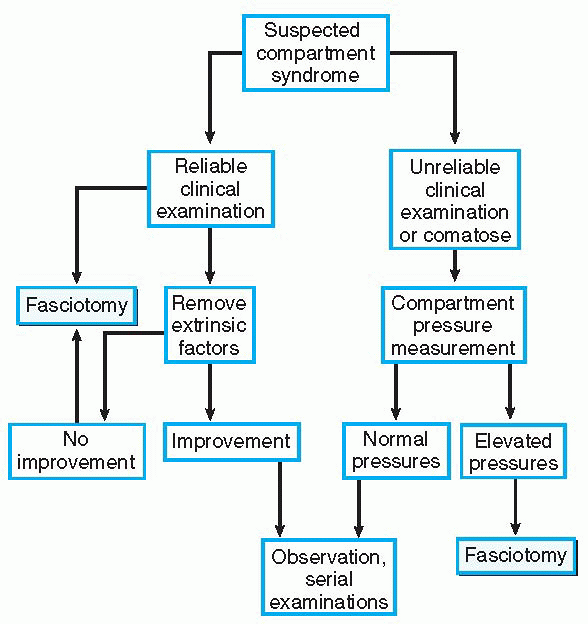

Algorithm 15-1 Algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of compartment syndrome.

|

-

Pain (particularly with the characteristics listed below)

-

□ Out of proportion to clinical scenario

-

□ Progressive

-

□ Poorly controlled by analgesics

-

□ Persistent despite fracture stabilization

-

-

Pain with passive stretch of muscles of compartment

-

Tenseness of compartment

-

Tenderness to palpation of compartment

-

Paresthesias in distribution of involved nerves (late)

-

Paralysis (late)

A noncommunicative, very young, or comatose patient

deserves special attention. Sometimes the only signs of compartment

syndrome are a child who is inconsolable or agitated, or one with an

increasing analgesic requirement. A high index of suspicion is

essential in this group of patients. One should have a low threshold

for measuring compartment pressures to supplement the clinical findings.

deserves special attention. Sometimes the only signs of compartment

syndrome are a child who is inconsolable or agitated, or one with an

increasing analgesic requirement. A high index of suspicion is

essential in this group of patients. One should have a low threshold

for measuring compartment pressures to supplement the clinical findings.

The diagnostic workup of compartment syndrome is outlined in Algorithm 15-1.

TREATMENT

Any patient with suspected compartment syndrome requires

immediate treatment. Sometimes the process can be halted by prompt

removal of extrinsic factors like a constricting bandage or cast.

Patients who do not respond to such measures require an urgent

fasciotomy.

immediate treatment. Sometimes the process can be halted by prompt

removal of extrinsic factors like a constricting bandage or cast.

Patients who do not respond to such measures require an urgent

fasciotomy.

Surgical Indications

The indication for fasciotomy is a clinical examination

consistent with compartment syndrome. In equivocal cases, compartment

pressures can help clarify the clinical picture. Pressures are measured

in all compartments with a commercial pressure-measuring device, slit

catheter, wick catheter, or arterial line transducer. The value

necessary for diagnosis varies; pressures over 30 mm Hg and pressures

within 30 mm Hg of diastolic blood pressure have both been proposed as

diagnostic. It must be emphasized that the entire clinical picture

should be weighed. An examination suggestive of compartment syndrome

outweighs nonsupportive pressure measurements. The morbidity of a

missed compartment syndrome considerably exceeds the morbidity of a

fasciotomy.

consistent with compartment syndrome. In equivocal cases, compartment

pressures can help clarify the clinical picture. Pressures are measured

in all compartments with a commercial pressure-measuring device, slit

catheter, wick catheter, or arterial line transducer. The value

necessary for diagnosis varies; pressures over 30 mm Hg and pressures

within 30 mm Hg of diastolic blood pressure have both been proposed as

diagnostic. It must be emphasized that the entire clinical picture

should be weighed. An examination suggestive of compartment syndrome

outweighs nonsupportive pressure measurements. The morbidity of a

missed compartment syndrome considerably exceeds the morbidity of a

fasciotomy.

Surgical Approaches

-

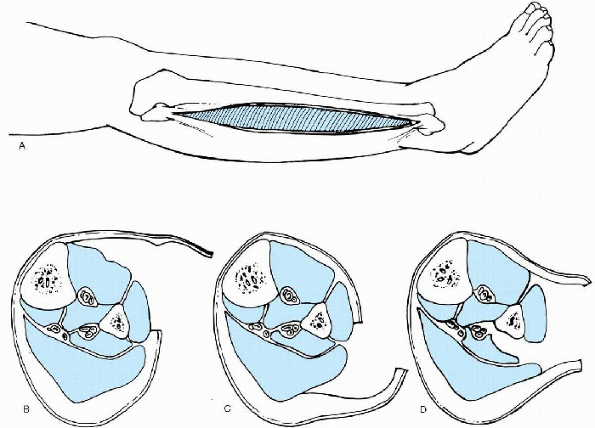

The standard fasciotomy in the leg is performed through two longitudinal incisions, one on each side.

-

□ The medial incision provides access to the posterior superficial and posterior deep compartments.

-

□ The lateral incision opens to the anterior and lateral compartments (Fig. 15-1).

-

□ Ideally, there should be a skin bridge of at least 6 cm between the incisions.

-

□ Careful dissection is necessary to

avoid injury to the superficial peroneal nerve in the lateral incision,

and both the saphenous nerve and vein in the medial incision.

-

-

Another technique is the single incision or perifibular approach.

-

□ A single lateral incision is made on the lateral side of the leg extending from the fibular head to the lateral malleolus.

-

□ Dissection anteriorly allows release of

the anterior and lateral compartments; posterior dissection exposes the

posterior superficial compartment. -

□ The interval between the lateral and posterior superficial compartments provides access to the posterior deep compartment (Fig. 15-2).

-

□ Proximally, the peroneal nerve is at risk for injury and should be avoided.

P.182 -

-

The partial fibulectomy technique is contraindicated in children.

-

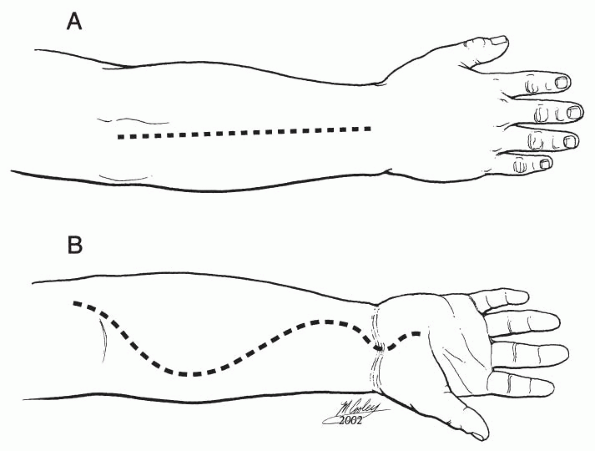

In the forearm, a volar Henry approach is used to release the superficial and deep flexor compartments.

-

□ The incision can be extended into the hand if a carpal tunnel syndrome is suspected.

-

□ A midline incision is used dorsally (Fig. 15-3).

-

-

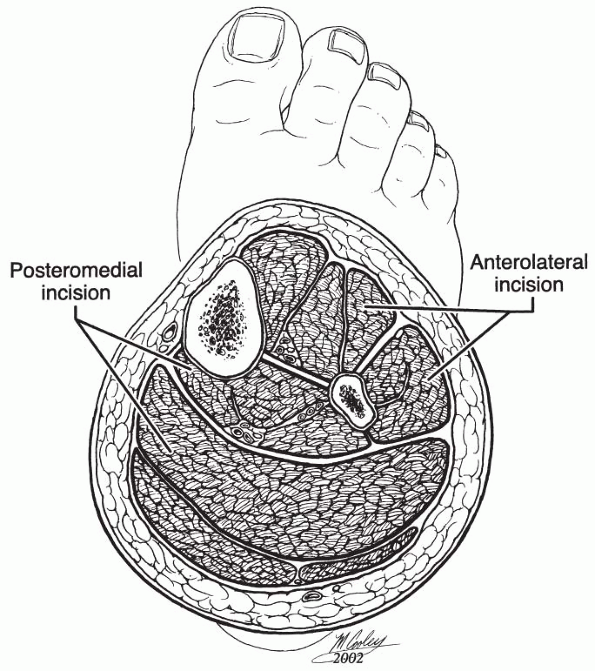

The nine compartments of the foot are decompressed through a single medial incision and two dorsal incisions.

-

□ The medial incision extends from behind the medial malleolus to the first metatarsal neck.

-

□ The dorsal incisions are centered over

the second and fourth metatarsals. Both approaches provide access to

all nine compartments.

-

-

If the compartment syndrome is diagnosed late, and myonecrosis is present, devitalized tissue is débrided.

-

□ The patient is returned to the operating room after 2 to 3 days for reexamination and further débridement if necessary.

-

□ Closure is attempted once all necrotic tissue has been removed and the wound is healthy.

-

|

|

Figure 15-1

Surgical technique for two-incision fasciotomy of the leg. (Adapted from Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, eds. Skeletal trauma in children. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994:84.) |

|

|

Figure 15-2 Technique of Davey, Rorabeck, and Fowler for decompression of leg compartments. (A) Lateral skin incision from fibular neck to 3 to 4 cm proximal to lateral malleolus. (B) Skin is undermined anteriorly, and fasciotomy of anterior and lateral compartments is performed. (C) Skin is undermined posteriorly, and fasciotomy of superficial posterior compartment is performed. (D)

Interval between superficial posterior and lateral compartments is developed. Flexor hallicus longus muscle is dissected subperiosteally off fibula and retracted posteromedially. Fascial attachment of tibialis posterior muscle to fibula is incised to decompress muscle. (Adapted from Davey JR, Rorabeck CH, Fowler PJ. Am J Sports Med 1984;12:391.) |

Results and Outcome

With early diagnosis and treatment, the results after fasciotomy are excellent. If necrosis has occurred, the patient

P.183

will have disability dependent on the extent of the muscle loss and nerve injury.

|

|

Figure 15-3 Surgical technique for fasciotomy of the forearm. (A) Dorsal incision. (B) Volar incision. (Adapted from Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, eds. Skeletal trauma in children. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1994:83.)

|

Postoperative Management

After uncomplicated fasciotomy, the limb is elevated for

5 to 7 days to decrease swelling. The child then returns to the

operating room for delayed primary closure or skin grafting if

necessary.

5 to 7 days to decrease swelling. The child then returns to the

operating room for delayed primary closure or skin grafting if

necessary.

SUGGESTED READING

Bae

DS, Kadiyala RK, Waters PM. Acute compartment syndrome in children:

contemporary diagnosis, treatment, outcome. J Pediatr Orthop

2001;21:680-688.

DS, Kadiyala RK, Waters PM. Acute compartment syndrome in children:

contemporary diagnosis, treatment, outcome. J Pediatr Orthop

2001;21:680-688.

Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Compartment syndromes of the lower leg. Clin Orthop 1989;240:97-104.

Heinrich

SD. Fractures of the shaft of the tibia and fibula. In: Beaty JH,

Kasser JR, eds. Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures in children, 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:1077-1119.

SD. Fractures of the shaft of the tibia and fibula. In: Beaty JH,

Kasser JR, eds. Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures in children, 5th ed.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:1077-1119.

Kadiyala RK, Waters PM. Upper extremity pediatric compartment syndromes. Hand Clin 1998;14:467-475.

Mars M, Hadley GP. Raised compartmental pressure in children: a basis for management. Injury 1998;29:183-185.

Matsen FA III, Veith RB. Compartmental syndromes in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1981;1:33-41.

Mubarak SJ, Carroll NC. Volkmann’s contracture in children: aetiology and prevention. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1979;61:285-293.

Silas

SI, Herzenberg JE, Myerson MS, et al. Compartment syndrome of the foot

in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995;77:356-361.

SI, Herzenberg JE, Myerson MS, et al. Compartment syndrome of the foot

in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995;77:356-361.

Willis RB, Rorabeck CH. Treatment of compartment syndrome in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1990;21:401-412.