Vascular Lesions

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.7 – Vascular Lesions

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.7 – Vascular Lesions

5.7

Vascular Lesions

Sean V. McGarry

C. Parker Gibbs

Hemangiomas are benign lesions originating from blood

vessels. There is some controversy in the distinction between

hemangiomas and vascular malformations. While histologically they

appear identical under the microscope, vascular malformations are

developmental irregularities that are usually latent and probably

present at birth. Hemangiomas are true neoplasms that can be either

active or latent. There are many histological subtypes of hemangiomas

that have subtle microscopic differences, but these are beyond the

scope of this text. Hemangiomas may involve one or more organs,

including bone, the central nervous system, the liver, the skeleton,

and skin and soft tissues. This chapter will discuss only lesions seen

in bone. Bone hemangiomas usually occur as isolated lesions, although

bone involvement may occur in conjunction with other organ systems when

hemangiomas occur as part of a regional or systemic disease process,

such as hemangiomatosis or skeletal/extraskeletal hemangiomatosis.

Maffucci’s syndrome is a combination of hemangiomas and multiple

enchondromas.

vessels. There is some controversy in the distinction between

hemangiomas and vascular malformations. While histologically they

appear identical under the microscope, vascular malformations are

developmental irregularities that are usually latent and probably

present at birth. Hemangiomas are true neoplasms that can be either

active or latent. There are many histological subtypes of hemangiomas

that have subtle microscopic differences, but these are beyond the

scope of this text. Hemangiomas may involve one or more organs,

including bone, the central nervous system, the liver, the skeleton,

and skin and soft tissues. This chapter will discuss only lesions seen

in bone. Bone hemangiomas usually occur as isolated lesions, although

bone involvement may occur in conjunction with other organ systems when

hemangiomas occur as part of a regional or systemic disease process,

such as hemangiomatosis or skeletal/extraskeletal hemangiomatosis.

Maffucci’s syndrome is a combination of hemangiomas and multiple

enchondromas.

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

-

Age: most common in fifth decade but may occur at any age

-

Gender: slight female predominance

-

Location: most frequently in the spine (vertebral body) and cranium

-

Frequency: Asymptomatic hemangiomas of the spine are thought to occur in up to 10% of the population.

Pathophysiology (Also see Fig. 11-32)

Most simply stated, hemangiomas are capillary-sized

proliferations of blood vessels occurring in bone. Hemangiomas of bone

are generally asymptomatic. They are often found incidentally on

radiographs taken in the work-up of other problems. When they occur in

the spine they can rarely expand the vertebral body and cause

neurological compromise. Pathologic fracture in the spine can also

cause neurological symptoms by impinging on the cord. Hemangiomas have

no potential for malignant degeneration.

proliferations of blood vessels occurring in bone. Hemangiomas of bone

are generally asymptomatic. They are often found incidentally on

radiographs taken in the work-up of other problems. When they occur in

the spine they can rarely expand the vertebral body and cause

neurological compromise. Pathologic fracture in the spine can also

cause neurological symptoms by impinging on the cord. Hemangiomas have

no potential for malignant degeneration.

Classification

-

Solitary osseous hemangiomas follow Enneking’s classification of benign tumors (see Chapter 4.2, Treatment Principles).

-

There are numerous histologic subtypes of

solitary hemangiomas, and the World Health Organization recognizes

various forms of more disseminated hemangioma-related lesions as well

as osseous glomus tumors and lymphangiomas (Box 5.7-1).

P.165

Box 5.7-1 Classification of Hemangiomas and Hemangioma-Related Lesions

|

Diagnosis

Physical Examination and History

Clinical Features

-

Asymptomatic or an incidental finding

-

In a symptomatic patient, vague, achy pain

-

In a subcutaneous bone, expansion of the bone may produce a mass or localized pain (Fig. 5.7-1)

-

In the spine, hemangioma can cause pathologic fracture and neurological compromise with or without fracture

Radiologic Features

-

Radiographs/computed tomography (CT) scans

-

Very characteristic “jail-cell striation”

on sagittal or coronal imaging; axial imaging demonstrates the

trabeculae as speckled areas (“polka-dot pattern”) of ossification (Fig. 5.7-2)

-

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

-

Usually bright signal on T2 imaging (Fig. 5.7-3) and significantly enhanced by contrast

-

Diagnostic Work-up Algorithm

-

Hemangioma of bone can usually be confirmed by radiographs or CT scan (Fig. 5.7-4).

-

Serial examinations can confirm the benign nature of the lesion, although growth of the lesion can occur in the growing child.

-

Any question of diagnosis can be confirmed with a biopsy.

Treatment

Surgical Indications/Contraindications

-

Asymptomatic lesions: Surgical indications in the asymptomatic patient are extremely limited.

-

Symptomatic lesions

-

Conservative treatment is offered

initially for symptomatic lesions and includes anti-inflammatory

medications, low-dose radiation, and sclerosing therapy. -

In spinal lesions in which expansion of

the bone is causing neurological symptoms, radiation therapy and

surgical intervention are reasonable alternatives. (Any surgical

intervention should probably include preoperative embolization.) -

In acute pathologic fractures of the

spine with neurological compromise, surgical intervention is generally

required to stabilize the spine and decompress the cord.

-

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

-

Surgical excision

-

Typically offered only for symptomatic spine lesions

-

Can be an option in symptomatic lesions of expendable bone (rare)

-

-

Radiation therapy

-

Used for inaccessible symptomatic lesions

-

Symptomatic lesions in patients for whom excision would cause unacceptable morbidity

-

-

Embolization

-

Typically used in combination with surgery to control intraoperative bleeding

-

Effect is usually only temporary.

-

-

Sclerosing therapy

-

Multiple different agents used

-

Mixed results

-

Preoperative Planning

-

Larger lesions considered for embolization therapy to prevent massive intraoperative blood loss

-

Balance nonmalignant nature of lesion against the morbidity associated with excision.

Surgical Goals and Approaches

-

The surgical goals for excision of a

hemangioma are the same as any other tumor: removal of the mass, a low

rate of recurrence, and acceptable perioperative and postoperative

morbidity. -

Because hemangiomas have essentially no

malignant potential, a higher recurrence rate is accepted to allow

closer margins in the rare symptomatic case that requires operative

intervention.

Techniques

-

En bloc excision of smaller lesions can be used to decrease surgical bleeding.

-

Radiation and/or embolization can be used in conjunction with surgical excision to decrease recurrence.

P.166

P.167

|

|

Figure 5.7-1

Rarely, osseous hemangiomas occur in the long bones, as in this case of a tibial hemangioma. The lesion is shown on plain anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs, CT (C,D), and MRI (E–G). In a subcutaneous osseous site such as this, an osseous hemangioma may cause pain and local tenderness. |

Complications

-

Oncologic complications

-

Recurrence

-

No risk of malignant degeneration

-

-

Surgical complications

-

Massive hemorrhage

-

Neurovascular injury secondary to anatomic location of the lesion

-

|

|

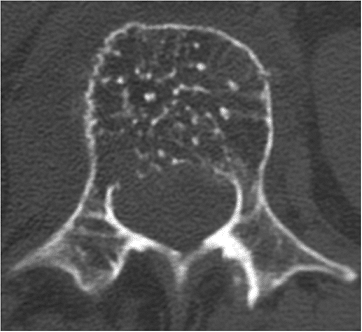

Figure 5.7-2

Axial-cut CT scan of L1 vertebrae demonstrates “speckled ossification” in the vertebral body, characteristic of hemangioma of bone. |

Results and Outcome

Surgery

-

Clean margins: very low recurrence rate

-

Contaminated margins: often results in recurrence

-

Recurrence may or may not be symptomatic and require re-excision.

-

Radiation

-

Radiation as sole treatment modality in vertebral hemangioma

-

Meta-analysis of 21 studies involving 63 patients

-

Complete remission 57%

-

Partial remission 32%

-

No response 11%

-

-

-

Radiation in combination with other modalities in treatment of vertebral hemangioma

-

Meta-analysis of 55 studies involving 210 patients

-

Complete remission 54%

-

Partial remission 32%

-

No response 11%

-

-

Embolization

-

Good as adjuvant to surgical excision to control bleeding

-

Only temporary control as lone treatment

Sclerosing Therapy

-

Mixed results

P.168

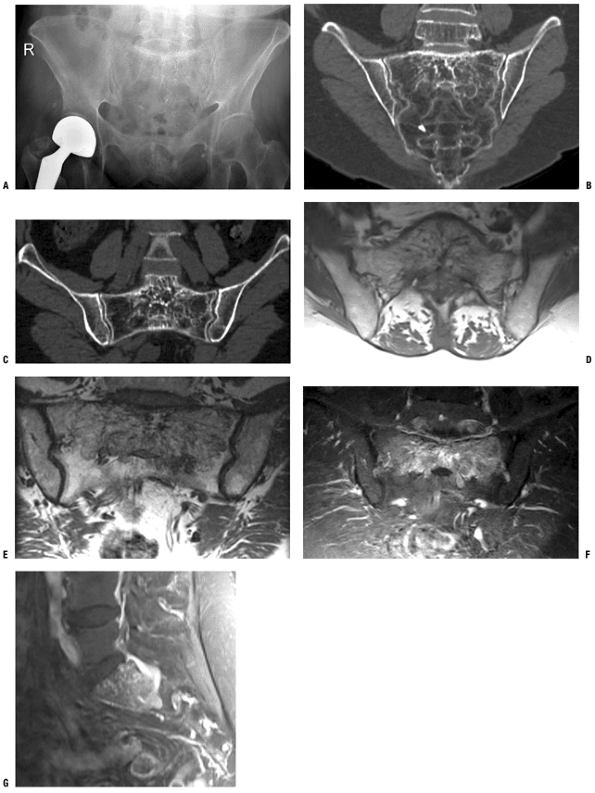

|

|

Figure 5.7-3 A sacral hemangioma is shown on pelvis x-ray (A), CT scans (B,C), and T1-weighted axial (D,E), T2-weighted coronal (F), and T2-weighted sagittal (G) MRIs.

|

P.169

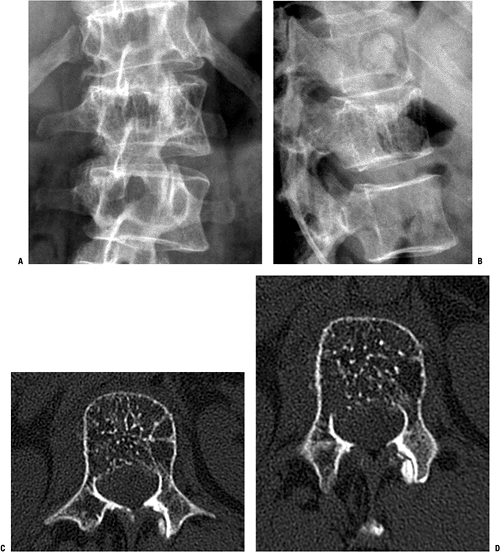

|

|

Figure 5.7-4 A typical vertebral hemangioma should be suspected based on the vertical striations often seen on plain radiographs (A) and shown best on the lateral view here (B). CT in this case confirms the diagnosis by showing the characteristic polka-dot pattern on axial imaging (C,D).

|

P.170

Postoperative Management

-

Immediate postoperative management

following surgical excision should include surgical drains and

compressive dressings to prevent seroma or hematoma. -

Precautions vary considerably depending

on the specific surgical intervention but may include protected weight

bearing to allow healing of involved bone.

Suggested Reading

Adler CP, Wold L. Haemangioma and related lesions. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds. Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone: Pathology and Genetics. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002:320–321.

Unni KK. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.