Pediatric Orthopaedic Conditions

physician’s office or an urgent/emergency care center. There is a long

list of possible causes to be considered. Important components of the

evaluation include a thorough history and a careful physical

examination (7).

-

History.

Acuteness of onset, pain, history of trauma or injury, constitutional

symptoms such as fever, malaise, chills; early morning stiffness and

motor milestone development (walked by 15–18 months). -

Past medical history. Birth history and any previous surgery, injuries, or illnesses.

-

Family History. Family history of childhood lower extremity conditions such as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH).

-

Physical examination.

The child should be undressed to an appropriate state. Older children

and teenagers should be provided with a gown or shorts. Toddlers and

small children can be examined in their diaper or underwear. The

physical exam should be tailored to each patient depending on the

symptoms at presentation. The physical exam of a child with a recent or

sudden onset of a painful limp or refusal to walk will be very

different from an examination of a child with a chronic, painless limp.-

An antalgic

gait is characterized by a decreased stance period on the affected limb

as well as a trunk shift over the affected limb during stance. -

Evaluation for limb length difference:

palpate the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) with the patient

standing. Then, with the patient supine, compare lengths of the lower

extremities with the legs extended. Also, compare lengths of the femurs

by flexing the hips and comparing the relative heights of the knees. -

Physical exam should also include the back, sacroiliac (SI) joints, and abdomen as well as the entire extremity involved.

-

Palpate the entire length of the limb.

-

Range of motion of the hip, knee, and

ankle joints. Particular attention should be paid to any erythema,

warmth, joint effusion, or focal tenderness. -

A thorough neurologic examination should also be completed.

-

-

The differential diagnosis

encompasses a broad range and depends on many factors including age,

symptoms, severity, acuteness of onset, and clinical findings on

physical exam (1,2).-

0 to 5 years old

-

Septic arthritis

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Transient hip synovitis

-

DDH

-

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease/osteochondroses-related conditions

-

Toddler’s fracture

-

“Nonaccidental injury” (child abuse)

-

Neurologic disorders (cerebral palsy, Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy)

-

Tumor [neuroblastoma, acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), benign tumors]

-

Discitis

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Congenital limb deficiency (femur, fibula, tibia)

P.68 -

-

5 to 10 years old

-

Septic arthritis

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Transient synovitis

-

Osteochondroses conditions such as Perthes, Kohler, and Osgood-Schlatter disease

-

Limb length difference

-

Tumor (ALL, Ewing sarcoma, benign bone tumors)

-

Neurologic disorders (hereditary motor sensory neuropathy)

-

Discitis

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Discoid meniscus

-

-

10 to 15 years old

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

-

Osteochondroses conditions such as Perthes and Sever disease

-

Hip dysplasia

-

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

-

Tumor (osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, benign bone tumors)

-

Osteochondritis desiccans

-

Idiopathic chondrolysis

-

-

-

Radiographic evaluation.

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain radiograph (x-ray) of the entire

length of bone involved, including joint above and below the area of

concern. Referred pain describes pain

attributed to one site or location by the patient but the source of the

pain is at a different site (e.g., knee pain in a patient with an SCFE

involving the hip joint). Referred pain is frequently seen with some

childhood conditions. -

Laboratory studies.

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation

rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP). If rheumatologic conditions

or spondyloarthropathies are being evaluated, include rheumatoid factor

(RF), antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-streptolysin (ASO) titer, Lyme

titer, and HLA B-27. -

Additional imaging studies.

-

Three-phase bone scan. Useful when source of pain is not easily localizable; sensitive but not specific.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Very sensitive and specific. Able to identify areas of bone marrow

edema, soft tissue edema, or fluid collections such as abscesses. -

Ultrasound.

Useful to look for hip joint effusions, subperiosteal or soft-tissue

abscesses. May also help guide aspiration of hip joint or soft tissue

abscess.CAUTION: If septic arthritis is suspected, a joint aspiration should be performed without wasting time waiting for the availability of other additional imaging studies.

-

-

History

-

Fever, lethargy, malaise, or other constitutional symptoms

-

Pain: location, severity, duration

-

Trauma/injury

-

Onset (sudden, gradual, etc.)

-

-

Physical evaluation

-

Observe posture of patient/posture of limb

-

Inspect swelling, redness, deformity

-

Palpate entire length of extremity, abdomen, spine for sites of pain, mass, warmth

-

Range of motion (ROM) active/passive, hip, knee, ankle joints

-

-

Radiograph. Obtain AP and lateral radiographs of the area identified as the location of the patient’s pain on physical examination.

-

Laboratory examination. EXTREMELY IMPORTANT:

-

CBC with differential (may be normal)

-

C-reactive protein (CRP) (most sensitive)

-

ESR

-

Blood culture (particularly in setting of fever/sepsis)

-

-

Differential Diagnosis.

When evaluating a patient with a fever, significant pain with attempted

range-of-motion, and/or refusal to bear any weight or to walk, the

primary physician should immediately notify the orthopaedic surgeon

with whom they wish to consult. As soon as the laboratory studies and

x-rays are available, the appropriate disposition of the child can be

determined.-

Septic arthritis.

Frequently affects the hip joint in toddlers and young children; may

also affect other joints of the lower extremity (knee, ankle) or the

upper extremity (shoulder, elbow, wrist). (See VIII.B for additional information.)-

Symptoms: fever, joint pain, restricted range of motion

-

Laboratory tests: CBC may be normal, CRP and ESR are elevated

-

Radiographs: frequently normal, may suggest hip joint effusion

-

Treatment plan: immediate referral to orthopaedist for evaluation and aspiration and/or surgical drainage as well as admission/intravenous (IV) antibiotics

-

-

Transient/toxic synovitis (see VIII.C for additional information)

-

Symptoms: severity of hip pain may vary, patient usually afebrile

-

Laboratory tests: normal or minimal elevation of CBC, ESR, and CRP

-

Radiographs: normal

-

Hip ultrasound: hip effusion

-

Treatment: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)/bed rest and re-evaluate in 24 to 48 hours

-

-

Osteomyelitis. A bacterial infection of the bone (see VIII.A for more information).

-

Symptoms: fever, pain localized over long

bone adjacent to joint, pain with joint ROM is less severe than that

seen with septic arthritis -

Laboratory tests: CBC may be normal, ESR and CRP elevated

-

Radiographs: early on, normal; later

(after 10–14 days), may show a lytic lesion in area of infection. This

is frequently adjacent to the physis (growth plate). -

Treatment:

-

Admission to hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy

-

Additional imaging (nuclear medicine vs. MRI)

-

Possible aspiration of painful area for culture

-

-

-

Fracture or other injury. If patient is too young to provide history, consider possible fracture or other significant injury.

-

History: patient fell or found lying on floor if injury unwitnessed

-

Physical exam: area of swelling, deformity, tenderness

-

Radiograph: look for fracture or physeal

separation. Children’s x-rays can be difficult to interpret because of

the presence of growth plates (physes). If necessary, consider

comparison x-rays of opposite limb. -

Treatment: splint injured limb and consult orthopaedic surgeon

-

-

SCFE (unstable/acute) (see VII.C)

-

Symptoms: adolescent child with sudden

onset of severe hip pain, inability to walk or bear weight on affected

limb. (For stable SCFE, the adolescent patient may complain of hip or

thigh pain but may be able to bear weight.) -

Physical exam: patient lies with hip flexed and externally rotated. Severe pain with any attempted ROM.

-

X-ray: obtain AP pelvis x-ray and cross-table lateral x-ray of affected hip. Femoral epiphysis is displaced relative to femoral neck.

-

Treatment: immediate referral to orthopaedic surgery for surgical stabilization.

-

-

-

Intoeing

-

Definition.

An internal foot progression angle during gait. The foot turns in

relative to the line of forward progression during walking. Intoeing is

a frequent cause for parental concern. An important part of the

evaluation should be listening to the concerns expressed by the parents

and answering their questions.

-

-

Physical examination. The patient should be undressed adequately to visualize the lower extremities.

-

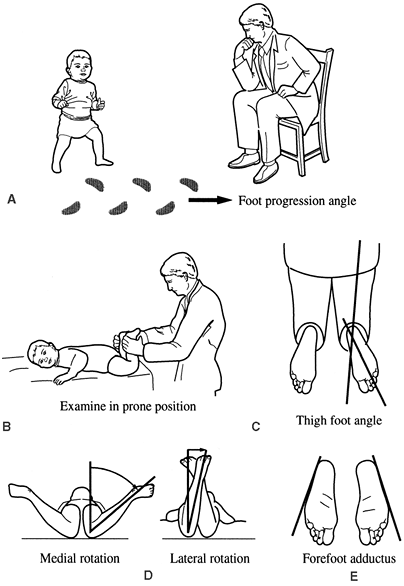

Observation: observe child walk in hallway. Note position of feet relative to line of forward progression (Fig. 5-1).

-

Examination: evaluate rotational profile. Position patient prone on examination table.

-

Hip internal (medial) and external (lateral) rotation (see Fig. 5-1D).

With patient prone and knees flexed to 90 degrees, rotate hip

internally and externally until you can feel the position of rotation

at which the greater trochanter of the hip is most prominent. Estimate

the angle between the tibia and a vertical position in order to

estimate femoral neck anteversion. -

Estimate thigh-foot axis and bimalleolar axis in order to assess tibial torsion.Thigh-foot axis: (see Fig. 5-1C) angle formed by line down the middle of the foot relative to line down length of thigh.Bimalleolar axis: angle

formed by a line passing through center of lateral malleolus and medial

malleolus relative to line perpendicular to long axis of thigh. -

Examine the plantar surface of the foot with the patient still in the prone position. Metatarsus adductus is defined as a curvature of the lateral border of the foot (see Fig. 5-1E).

-

-

-

Causes

-

Increased femoral anteversion: rotational twist in femur turns leg in while walking.

-

Internal tibial torsion: twist in tibia turns lower leg inward.

-

Metatarsus adductus: curvature of foot turns toes/forefoot inward.

-

-

Discussion.

For the majority of children, treatment of these conditions consists of

education of the parents, reassurance, and observation. Intoeing is

frequently seen in young patients and is a normal part of skeletal

development for many children. The most frequent causes are increased

femoral anteversion, internal tibial torsion, or metatarsus adductus.

Normal femoral anteversion in the newborn

is 40 to 45 degrees. For most children, this gradually remodels with

growth over time and will have improved by age 6 to 8 years old. At

skeletal maturity, normal femoral anteversion is approximately 10 to 15

degrees. Increased femoral anteversion is

femoral anteversion that persists longer than usual and is frequently

associated with increased ligamentous laxity. Children with

developmental delays or abnormal motor developmental conditions such as

cerebral palsy will also frequently exhibit increased femoral

anteversion. There are no forms of bracing, shoe-wear, or therapy that

will help femoral anteversion resolve. For the vast majority of

patients, it does not cause functional nor painful conditions later in

life and should simply be observed (3). -

Internal tibial torsion

is frequently seen as a cause of intoeing in infants and toddlers and

also gradually corrects with time. It will correct more quickly than

femoral anteversion and usually has improved by age 2 to 3 years. -

Metatarsus adductus

refers to a curvature of the lateral border of the foot. This is a

frequent finding in newborn children and is often flexible. Simple

massage and stretching can be performed by the parents for the first 6

months of life. If no improvement is seen, one may then consider a

course of treatment with reverse-last shoes or bracing. If the foot

does not appear flexible, a course of serial casting may be considered.

|

|

Figure 5-1. Rotational profile. A: Observation of foot-progression angle. B: Examination of child in prone position to evaluate torsional deformity of the lower extremities. C: Thigh-foot angle. D: Hip internal (medial) rotation and external (lateral) rotation. E: Forefoot (metatarsus) adductus.

|

-

Terminology

-

Genu varum (“bowed legs,” genu-knee, varum/varus): the distal segment of the lower leg is aligned toward or close to the midline.

-

Genu valgum (“knock knees,” genu-knee, valgum/valgus): the distal segment is aligned away from the midline.

-

-

Physical examination.

The child should be undressed appropriately so that both lower

extremities can be evaluated. The child should be assessed standing and

again supine on the examination table. The amount of angulation at the

knee can be assessed in two ways.-

Femoral-tibial angle: angle between thigh and lower leg

-

One can also measure and record the distance between bony landmarks.

-

Intercondylar distance (genu varum): the distance between the medial femoral condyles of the knees.

-

Intermalleolar distance (genu valgum): the distance between the medial malleoli of the ankles.

-

-

-

Radiographic evaluation. For either genu varum or genu valgum, standing AP hip to ankle radiographs of both lower extremities should be obtained. The mechanical axis as well as the anatomic axis of the lower extremity is measured. In young children with genu varum, the metaphyseal-diaphyseal angle is measured.

-

Causes

-

“Physiologic”: part of the normal

development. Most children who are referred for evaluation have a

physiologic form of bowing. Children undergo an evolution of their

lower extremity alignment during the first 6 years of life.-

Birth to age 2: genu varum

-

Age 2 to age 4: genu valgum

-

Age 4 to age 6: continued gradual correction into relatively “mature” alignment of mild genu valgum anatomically (4).For children who do not fit this pattern, are of

adolescent age, or appear to have asymmetric alignment of their lower

extremities, other possible causes should be explored.

-

-

Tibia vara (Blount disease)

is an abnormal varus alignment of the knee due to altered growth of the

medial portion of the proximal tibial physis. There is an infantile form for children older than age 2 years and an adolescent form, frequently associated with obesity. -

Other causes could include:

-

Coxa vara (a congenital varus deformity of the proximal femur)

-

One of the various forms of skeletal dysplasia.

To help evaluate this, obtain additional radiographs. An x-ray of the

hands, shoulders, spine, hips, and knees can help evaluate other

potential sights of growth abnormalities. -

One of the forms of rickets

(such as familial hypophosphatemic rickets). To evaluate this further,

consider obtaining laboratory studies including vitamin D; parathyroid

hormone (PTH); alkaline phosphotase; calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus

levels; and consider obtaining an endocrinology consultation.

-

-

-

Treatment

-

For

physiologic conditions, treatment usually consists of observation.

Inform the patient’s parents of the expected course and communicate the

findings and recommendations to the patient’s primary physician.

Continued observation can be performed during routine well-child

checks. If the child’s alignment varies from what is expected, the

child can return for reevaluation. -

Children

with conditions which do not fit the typical “physiologic” pattern

should be referred for further evaluation. Further treatment consists

of establishing the underlying cause as well as developing an

appropriate treatment plan. After the diagnosis has been determined,

treatment may consist of:-

Observation

-

Hemiepiphyseal stapling

-

Hemiepiphysiodesis

-

Tibial and/or femoral osteotomyThese should be performed by physicians who are well

experienced in planning and performing the appropriate procedures and

are able to provide follow-up care.

-

-

-

Clubfoot (talipes equinovarus)

-

Description.

A congenital deformity of the foot comprised of ankle equinus, hindfoot

varus, and adduction and supination of the midfoot and forefoot. The

foot “turns in” and “curves under” compared with the normal. -

Incidence.

1 in 1,000 live births, unilateral in 60% of patients, and the ratio of

boys to girls is 2:1. There may be a positive family history. -

Etiology. Multiple theories exist with the most likely cause being multifactorial.

Theories include arrested fetal development, abnormal intrauterine

forces, abnormal muscle fiber type, abnormal neuromuscular function,

and germ plasm defects. -

Prenatal considerations include breech position, large birth weight, and oligohydramnios.

-

Associated conditions include arthrogryposis, myelodysplasia, congenital limb anomalies, and various syndromes.

-

Physical examination.

A careful evaluation should include not only examination of the child’s

feet, but also the child’s upper extremities, back, spine, and hips in

order to look for other associated conditions. Examination of the foot

should include evaluation of the ankle dorsiflexion, the hindfoot

position, curvature of the lateral border of the foot, and the forefoot

position as well as an assessment of the degree of flexibility of the

foot. Deep posterior and medial creases are usually present. -

Radiographic evaluation.

Radiographs in the newborn period are not useful because the tarsal

bones are not well ossified. Radiographs may be useful after age 3

months for planning or evaluating surgical treatment. They are ordered

less often in nonoperative treatment as the physical examination is

more useful for clinical decision making. When x-rays are ordered, the

most useful images are an AP view and a lateral view in a position of

maximum dorsiflexion. Kite angle is the

angle subtended by the long axes of the calcaneus and the talus on the

AP view. This angle is normally between 20 and 40 degrees. In the

clubfoot, this angle is less than 20 degrees with relative parallel

alignment of the talus and calcaneus. The relationship of the talus and

calcaneus should also be assessed on the lateral view. Again, in the

clubfoot, this shows relative parallel alignment compared with the

normal foot. -

Treatment.

The goals of treatment are to achieve a plantigrade, flexible, painless

foot. In the early half of the 20th century, Kite published high levels

of satisfactory results with his casting technique. The later half of

the 20th century saw the emergence and rise in popularity of the

surgical treatment of clubfoot as described by such authors as Turco,

Carroll, Crawford, Simmons, and McCay (5). The

dawn of the 21st century has seen renewed interest in the role of

nonoperative treatment using the method developed by Ponseti. His

experience has produced impressive results at long-term follow up and

is gaining more widespread acceptance and support (6).

-

-

Flat feet (pes planus)

-

Definition. Feet in which the medial longitudinal arch is absent resulting in hindfoot valgus and forefoot supination.

-

Presentation

-

Parental concerns regarding the appearance and shape of the foot

-

Pain

-

Difficulties with shoe wear

-

-

Patient history.

It is important to note when the foot position was first noticed,

whether the foot condition causes problems with function or pain, and

any family history of ligamentous laxity or flatfeet. -

Physical examination

-

Observe the foot while the patient stands and walks. Note presence or absence of medial longitudinal arch.

-

Inspect the foot for calluses and pressure areas over bony prominences.

-

When the patient is standing, have him or

her stand on tiptoe to assess mobility of the hindfoot. If the hindfoot

moves from valgus when plantigrade to varus with standing on tiptoe and

the foot forms an arch when on tiptoe, then the foot is “flexible.” If it does not correct, it is considered “rigid.” -

Assess the length of the Achilles tendon by examining the range of ankle dorsiflexion.

P.74 -

-

Radiographic examination.

For young children with a painless, flexible flat foot, no radiographs

are indicated. If the flat foot is painful or rigid, then standing AP,

lateral, and oblique radiographs of the foot should be obtained. -

Flexible flat feet.

The flexible flat foot is a relatively common condition, although the

true incidence is unknown. Most young children start with a flexible

flat foot before developing a medial longitudinal arch during the first

decade of life. Most children are symptom-free, and no treatment is

warranted. For the older child or adolescent with a flexible flat foot

who experiences aching or discomfort associated with particular

activities, one may wish to use an orthotic to support the arch. If the

foot is flexible but there is a contracture of the Achilles tendon, one

should prescribe a course of physical therapy for a heelcord stretching

program. If the patient with an Achilles tendon contracture remains

symptomatic despite physical therapy, one may consider injection of

Botox into the calf muscle, possibly in conjunction with a stretching

cast. For patients that fail conservative therapy, some authors support

surgical correction of the hind foot valgus deformity in conjunction

with lengthening the tight gastrocnemius (7). This is rarely necessary in the growing child with a flexible flat foot deformity. -

Rigid flat feet. The most common cause for a rigid flat foot is a tarsal coalition. This is an incomplete separation of the tarsal bones during fetal development. The two most common types are the calcaneonavicular and the talocalcaneal

coalition. The calcaneonavicular coalition may be best seen on the

oblique foot radiograph. The talocalcaneal coalition may be seen on an

axial (Harris) radiograph of the foot. If further radiographic imaging

is required, a computed tomography (CT) scan of both feet is the study

of choice. -

If tarsal coalition has been excluded as the cause for the rigid flat foot, other possible causes include a congenital vertical talus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) involving the subtalar joint, osteochondral fractures of the subtalar joint, or neuromuscular conditions.

-

Treatment of

the rigid flat foot. The goal of treatment is to achieve a pain-free,

asymptomatic foot. Approximately 75% of patients with tarsal coalitions

are asymptomatic. Frequently, the onset of pain coincides with the

transition of the coalition from a fibrous or cartilaginous junction to

a bony bar. For the calcaneonavicular bar, this occurs around ages 8 to

12 years old; for the talocalcaneal bar, this usually occurs between 12

and 16 years of age. Nonoperative treatment consists of applying a

short-leg walking cast for 6 weeks followed by use of a molded

orthotic. This results in a resolution of the patient’s symptoms in a

large number of patients. For patients who do not respond to casting

treatment or for whom the symptoms recur, surgery is indicated.

Operative treatment usually consists of excision of the coalition along

with interposition of fat, muscle, or tendon to prevent recurrence. For

patients with a talocalcaneal coalition that comprises more than 50% of

the subtalar joint surface, some authors have questioned the role of

resection of the coalition. For patients with severe degenerative

arthrosis of the subtalar joint or persistent pain following previous

resection, a triple arthrodesis should be considered (8,9).

-

-

Bunions (hallux valgus)

-

Definition.

An abnormal bony prominence of the medial eminence of the first

metatarsal associated with a hallux valgus deformity of the great toe.

It is frequently associated with a medial deviation of the first

metatarsal (metatarsus primus varus). -

Patient history.

These patients are most often adolescent or teenage girls with

complaints of pain over the medial eminence, difficulty with shoe wear,

or concerns regarding appearance. There may be a positive family

history. -

Physical examination.

Clinically assess presence of hindfoot valgus and presence of a

coexisting flat foot in addition to presence and severity of hallux

valgus deformity. Evaluate degree of angulation as well as rotation of

great toe. -

Radiographic evaluation.

Standing AP and lateral radiographs of the foot are recommended. On the

AP radiograph, one can assess the following parameters:-

First-second intermetatarsal angle (normal is <9 degrees)

-

First metatarsal-phalangeal angle (normal is <15 degrees)

-

Length of the first metatarsal

-

Congruency of first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint

-

-

Treatment. It is important to distinguish the functional

problems that the patient is experiencing as well as the patient’s and

the parents’ concerns. In the adolescent patient in whom the primary

concern is the appearance of the foot, every effort should me made to

educate and counsel the family. For patients with a symptomatic hallux

valgus deformity, strong consideration should be accorded to postponing

any surgical treatment until skeletal maturity is reached because there

is a high recurrence rate of bunions in adolescent patients. If surgery

is considered, careful examination of the foot is necessary to correct

all of the underlying deformities, thus decreasing the risk of

recurrence and increasing the likelihood of patient satisfaction. For

patients with an underlying flexible flat foot condition, initial

treatment should consist of a custom-molded, flexible medial-arch

supporting foot orthotic. This will frequently correct the foot

deformity and improve the hallux valgus deformity as well. -

Surgical options. There are numerous surgical options.

-

Soft-tissue procedures

-

Medial capsule advancement of first MTP joint

-

Excision of the medial eminence of the metatarsal head

-

Adductor hallucis release

-

-

Bony procedures

-

Distal first metatarsal osteotomy (Chevron, Mitchell)

-

Proximal first metatarsal osteotomy

-

First metatarsal double (proximal and distal) osteotomy as described by Peterson (10)Geissele reported that the reduction of the

intermetatarsal angle is the factor that correlates most highly with

both decreased risk of recurrence of angular deformity and with patient

satisfaction (11).

-

-

P.75 -

-

History

-

Trauma/injury

-

Swelling of joint

-

Locking/buckling of knees

-

Location of pain

-

Association of pain with specific activities (running, descending stairs, sitting)

-

-

Physical evaluation

-

Knee ROM

-

Hip ROM (remember referred pain from hip)

-

Effusion of knee joint

-

Joint line tenderness

-

Tenderness over patella/tibial tubercle

-

Assess ligamentous stability

-

-

Radiograph examination.

Obtain AP/lateral radiographs of knee to evaluate for any bony

abnormalities. For evaluation of patella alignment or patella-related

pain, obtain AP/lateral and “merchant” view or “sunrise” view of knee.

For concern regarding possible locking or catching of the knee such as

with osteochondritis dessicans (OCD) (see below), obtain AP/lateral and

“notch” view radiographs of knee. -

Differential Diagnosis

-

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

-

Definition.

Previously termed “chondromalacia patellae” or “anterior knee pain

syndrome,” it describes a condition in which the pain is attributed to

the patellofemoral joint. It typically is characterized by pain

localized to the front of the knee. -

Patient history.

Adolescent girls are affected more often than boys. Symptoms may occur

gradually or after previous knee injury; usually not associated with

specific trauma. There are no symptoms of locking or buckling. Pain is

frequently associated with activities such as walking, running,

descending stairs, and sitting for prolonged periods. -

Physical examination.

One should include a thorough examination of the knee, paying

particular attention to evaluate tracking of the patella, patella

mobility medially and laterally, and Q-angle (alignment of extensor

mechanism measured by angle of line from ASIS to patella and line from

patella to tibial tubercle). Also assess the lower extremity rotational

profile (see III.C.2) -

Radiographs.

AP, lateral, and patella views should be obtained to evaluate for

evidence of patellar tilt as well as to rule out other potential

sources of knee symptoms such as OCD and bony lesions. -

Treatment.

Most patients with patellofemoral knee pain respond to a course of

conservative treatment consisting of hamstring stretching in addition

to closed-chain quadriceps [specifically vastus medialis obliquus (VMO)

strengthening]. This may be augmented by use of a patellar-taping

program or a patella-stabilizing neoprene knee sleeve in some patients.

-

-

Acute patella dislocation

-

Patient history.

Patients may have experienced a traumatic or a nontraumatic patella

subluxation or dislocation. The patella dislocates laterally. The

patient may be tender over the medial retinaculum and a joint effusion

may be present. -

Radiographic evaluation.

AP/lateral/patella views of the knee should be closely evaluated for

any evidence of osteochondral fragments. The patella may knock off an

osteochondral fragment from the lateral femoral condyle within the

process of dislocating or relocating. -

Treatment. If

osteochondral fragments are present, the knee should be evaluated

arthroscopically. Very large fragments may need to be replaced and

internally fixed; smaller fragments may simply be removed. If no

osteochondral fracture is identified, treatment may consist of a short

period of immobilization with a soft-sided knee immobilizer followed by

a program of quadriceps strengthening exercises.

-

-

Chronic patella instability

-

Patient history.

Some patients may have recurrent patella subluxation/ dislocation

episodes. The initial course of treatment should consist of physical

therapy for quadriceps strengthening exercises. If these are not

successful in achieving improvement of the instability, surgical

stabilization may be indicated (12).

-

-

Osgood-Schlatter disease

-

Presentation.

One in the family of conditions known as “osteochondroses,” this is an

inflammation at the junction of the patellar tendon to the tibial

tubercle. It most often occurs in girls aged 10 to 12 and boys aged 12

to 14. The patient usually complains of painful swelling over the area

of the tibial tubercle as well as pain associated with activities such

as running or jumping sports. Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is a related condition arising at the proximal or distal ends of the patella. -

Treatment. Consists of hamstring and quadriceps stretching, NSAIDs, periodic ice to the area, and modification of activities.

-

-

Discoid meniscus

-

Presentation.

Patients with a discoid meniscus may have knee pain as early as age 4

years. Most patients are first seen between ages 6 and 12 years or

older. The incidence varies and is estimated to be from 3% to 5% in

Anglo-Saxons and as much as 20% in Japanese. The majority of cases

involve the lateral meniscus. Patients usually have complaints of

snapping or popping of the knee. -

Physical examination. Examination of the knee may reveal snapping with flexion of the knee. Unstable menisci may snap or pop in extension.

-

Classification.

There are three principal types. Type I is stable, complete. Type II is

stable, incomplete. Type III is unstable because of the absence of the

meniscotibial ligament. -

Treatment.

For stable discoid lateral meniscus, arthroscopic sculpting of the

meniscus to a normal configuration is indicated. If it is unstable,

stabilization with a capsular suture is recommended (13).

-

-

Ostochondritis Dessicans (OCD)

-

Definition.

This is a condition of unknown etiology that results in vascular

changes of the subchondral bone in the femoral condyle which may lead

to fragmentation or separation of the fragment along with the overlying

cartilage. It most often occurs in adolescents and is more often in

boys than in girls. -

History

-

Nonspecific knee pain

-

Knee swelling after activities

-

No history of acute trauma or injury

-

With or without catching or locking of knee

-

-

Physical examination. Mild swelling may be present, tenderness over femoral condyle.

-

Radiographic examination.

AP/lateral/notch views of knee; notch view may show lesion most

effectively. Lateral view may also show lesion on posterior aspect of

femoral condyle. -

MRI: assess “stability” of fragment based on continuity of articular cartilage and subchondral bone.

-

Treatment depends on age of patient and stability of fragment.

-

Skeletally immature patient with stable lesion:

-

brief period of immobilization

-

restriction of activities

-

-

Patient near or at skeletal maturity or

unstable lesion: consider arthroscopic evaluation, possible drilling

and internal stabilization.

-

-

-

Miscellaneous

-

Referred pain

-

Definition. Pain originating in one location but localized by the patient as arising from a nearby, different location.

-

Many children complain of lower extremity

pain, and the clinician’s challenge is to determine the source of the

symptoms. Children and adolescents (as well as adults) may have

referred pain in which disorders occurring at one site present with

pain at a distal location. A classic example is the overweight

adolescent boy with knee pain. An exhaustive evaluation of the knee

reveals no obvious cause of his symptoms. However, a careful and

thorough examination of the entire lower extremity reveals a SCFE of

the hip. To avoid the common pitfalls, one must consider all of the

diagnostic possibilities and complete a thorough evaluation.

-

-

Tumors

-

Definition.

Patients with leukemia or bone tumors often present with bone or joint

pain. If history and physical exam are not consistent with other causes

of pain, consider possible malignancies including

P.78

Ewing

sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, etc.

Obtain laboratory tests and radiographs/imaging studies appropriately.

-

-

P.77 -

-

Developmental Dysplasia of the HIP (DDH)

-

Definition. A

spectrum of disorders ranging from complete dislocation of the femoral

head to a reduced hip joint with acetabular dysplasia. -

Incidence. Approximately 1 in 1,000 live births.

-

Risk factors:

include first born, female, breech position in utero, oligohydramnios,

and a positive family history. It has also been associated with other

congenital conditions including congenital muscular torticollis,

metatarsus adductus, and clubfeet. -

Physical examination.

In the newborn child or young infant, physical examination should start

with a careful evaluation of the other parts of the child other than

the hips, including the spine, neck, and upper and lower extremities.

Then, focus examination on the hips, trying to detect any evidence of

instability. The clinical tests performed include the Barlow/Ortolani

and Galeazzi tests. The Barlow and Ortolani

tests are performed with the clinician stabilizing the pelvis with one

hand and grasping the child’s femur with the other, placing the thumb

over the medial femoral condyle and the long finger over the greater

trochanter. The hip is flexed to 90 degrees and held in neutral

abduction. The Ortolani maneuver consists of abducting the hip and

trying to detect the “clunking” sensation of the dislocated femoral

head relocating into the acetabulum. Likewise, the Barlow test consists

of two maneuvers. The first consists of adducting the hip with gentle

longitudinal pressure to provoke the hip to dislocate or subluxate. The

second maneuver is the same as that described for the Ortolani maneuver

to achieve reduction of the dislocated hip. The Galeazzi

test consists of comparing the height of the knees with the hips flexed

to discern any apparent femoral shortening. One should also check for

symmetric degrees of hip abduction as well as for asymmetry of the

perineal skin folds. Finally, DDH can be bilateral, which can be easily

missed clinically because there is no apparent asymmetry. These

children may first come to attention after walking age, with increased

lumbar lordosis, limb length difference, or a “waddling gait.” -

Radiographic evaluation.

In the young infant, ultrasound is the modality of choice to detect any

evidence of hip abnormality. The ultrasound allows a static assessment

of acetabular development (alpha and beta angles) and percentage of

femoral head coverage as well as dynamic assessment of femoral head

stability with stress maneuvers. In children older than 6 months, plain

AP radiographs are sufficient. -

Treatment

-

Age 0 to 6 months. In the newborn child up to 6 months of age, treatment consists of abduction bracing, usually performed with a Pavlik harness.

This is usually applied at the time the instability is noted. It may

also be used for children with a clinically stable hip but who have

significant acetabular dysplasia noted on ultrasound. Moreover, the

adequacy of the reduction or positioning in the Pavlik harness can be

evaluated with ultrasound. There have been several reports in the

literature of “Pavlik harness disease” in which the femoral head was

not adequately reduced in the acetabulum while in the harness, leading

to progressive deformation of the posterior wall of the acetabulum and

exacerbation of the dysplasia. If an adequate, concentric reduction of

the femoral head cannot be achieved by 4 weeks after the harness has

been applied, treatment with the Pavlik harness should be abandoned (14,15). -

Age 6 to 18 months or the child who fails Pavlik harness treatment.

Treatment for this group is aimed at achieving a satisfactory,

congruent, stable reduction. This is achieved by performing either a closed or an open reduction. Historically, traction has been employed preoperatively in

P.79

order to decrease the risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head

after closed reduction. An arthrogram is frequently performed at the

time of the closed reduction. If the hip is noted to have a narrow

“stable zone,” a limited adductor release may be performed to improve

stability. If a concentric reduction is not achievable or if excessive

force is required to maintain the reduction, then an open reduction may

be performed. Popular methods for performing the open reduction include

an anterolateral approach and the medial approach (14). -

Age older than 18 months.

Some authors still advocate a trial of preoperative skin traction

followed by attempted closed reduction. Alternatively, one can consider

open reduction performed in conjunction with femoral shortening to

reduce soft-tissue tension and thereby decrease risk of avascular

necrosis. If significant acetabular dysplasia is present, a pelvic

osteotomy may also be performed (16). -

Secondary procedures.

For older children with persistent acetabular dysplasia or persistent

hip subluxation, secondary procedures may take the form of femoral or

pelvic osteotomies. Adolescents or young adults may present with hip

pain from previously undiagnosed dysplasia. They may be candidates for

a redirectional pelvic osteotomy.

-

-

-

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease

-

Definition. Idiopathic avascular necrosis to the femoral head in children.

-

Presentation.

Most often affects children aged 4 to 8 years; however, it may affect

children as young as 2 or as old as 12 years. The ratio of incidence in

boys to girls is 4:1. The disease may be bilateral in 10% of patients.

Patients frequently have younger skeletal age than cohorts. Frequently,

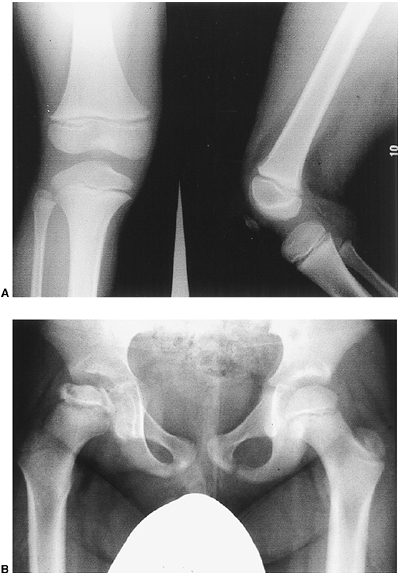

the disease presents as a painless limp (Fig. 5-2). -

Etiology: idiopathic. It has been associated with abnormalities of thrombolysis as well as deficiencies of protein C, protein S, or thrombolysin.

-

Differential diagnosis.

If bilateral hip involvement is present on radiograph, then other

possible etiologies should be excluded, including renal disease,

hypothyroidism, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia or spondyloepiphyseal

dysplasia, systemic corticosteroid use, storage disorders, and

hemoglobinopathies. -

Stages.

Waldenström originally described evolutionary stages that the disease

course follows. These have been modified from the original description

to include the following:-

Initial stage. Femoral head appears sclerotic early in the course of the disease.

-

Fragmentation stage.

Presence of subchondral fracture (Salter sign) is hallmark of onset.

The femoral head develops “fragmented” appearance on radiograph as

necrotic bone undergoes resorption. -

Reossification stage. There is evidence of healing; coalescence of femoral head fragmentation begins to occur.

-

Healed stage. Reossification is complete. Femoral head returns to predisease density. Any remaining deformity is permanent.

-

-

Classification systems. To describe and to compare the results of treatment, various classification systems have been described.

-

Catterall. Four-part system (I–IV) based on the amount of femoral head involvement

-

Salter-Thompson. Two part system (A, B) simplified to less than 50% or greater than 50% involvement of femoral head.

-

Herring:

Recently revised to a four-part system (A, B, BC, C) based on height of

lateral “pillar” (lateral one third of femoral epiphysis).

-

-

Treatment.

For patients with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, it is important to

determine which patients will benefit from treatment as well as how to

treat them.Risk factors for a poor prognosis include:-

Older age at presentation (>8 years old)

-

Greater degree of involvement of the femoral head using any of the above classification systems.

![]() Figure 5-2. A 6-year-old boy with a 1- to 2-month history of limping and right knee pain. A: Radiographs of the knee are normal. B: An AP pelvis radiograph reveals changes in the right hip consistent with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.P.80P.81The hallmarks of treatment consist of:

Figure 5-2. A 6-year-old boy with a 1- to 2-month history of limping and right knee pain. A: Radiographs of the knee are normal. B: An AP pelvis radiograph reveals changes in the right hip consistent with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.P.80P.81The hallmarks of treatment consist of:-

Maintaining hip range of motion

-

“Containment” of the femoral head in the acetabulum.For younger patients or patients with less involvement

of the femoral head, treatment may consist primarily of NSAIDs,

physical therapy, and restriction of activities to maintain hip range

of motion. For older children, especially those who have more

involvement of the hip (and therefore a worse prognosis), treatment may

consist of surgical containment of femoral head by femoral and/or

pelvic osteotomies (17). Abduction bracing was used historically but now is used very rarely.

-

-

-

-

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis (SCFE)

-

Definition. A

disorder of the upper femur in which there is a separation (acutely or

chronically) of the femoral epiphysis from the femoral neck through the

region of the physis (growth plate). The femoral head becomes

positioned posterior and inferior relative to the femoral neck. -

Incidence.

Approximately 3 in 100,000; boys more frequently than girls. Bilateral

involvement occurs in between 20% and 60% of cases. SCFE is seen most

frequently in boys aged 12 to 16 years and in girls aged 10 to 14

years. SCFE is associated with obesity, with more than half of affected

individuals weighing greater than the 95th percentile. (Note: Not all

patients with SCFE are obese.) Patients with an underlying hormonal or

endocrine disorder have an associated increased risk for development of

SCFE. For patients with an unusual presentation such as atypical age

(before age 10), bilateral involvement at presentation, or with other

signs of possible endocrine abnormalities, a careful evaluation for

endocrine disorders including hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism or

hypogonadism should be conducted. -

Classification

-

Temporal. One

method of classification is based on duration of symptoms. Acute is

less than 3 weeks, chronic is greater than 3 weeks, and

acute-on-chronic is a sudden exacerbation of subclinical symptoms of

long-standing duration. -

Stability. This classification system has gained greater popularity because it appears to be clinically more useful. A patient with a stable SCFE is able to walk without assistance, with mild pain, or a slight limp. Patients with an unstable SCFE are unable to walk or to bear weight. Unstable SCFEs are associated with a higher rate of complications (18).

-

Displacement.

Classified according to the amount of displacement of the femoral head.

This may be represented as a percentage of the femoral neck width or as

an angular value measured by the lateral head-shaft angle.

-

-

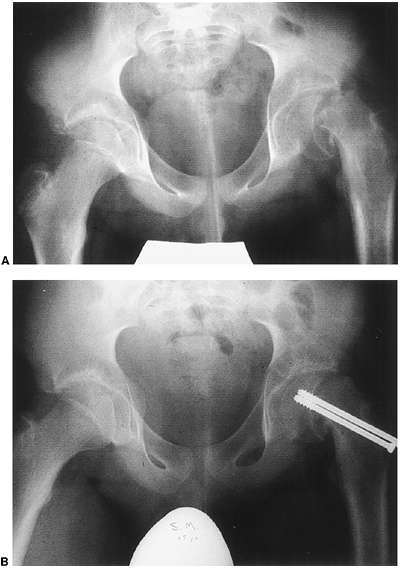

Treatment. The most widely recommended form of treatment is surgical stabilization with percutaneous pinning in situ. For a stable SCFE, this can usually be accomplished with a single, cannulated screw inserted under fluoroscopic control (19).

The aim of the procedure is to insert the screw perpendicular to the

femoral head in both the AP and lateral planes with close attention to

avoid penetrating the femoral head and entering the hip joint. In cases

of an unstable SCFE, a second screw may be inserted to further

stabilize the femoral head (Fig. 5-3). -

Complications. The primary complications associated with SCFE are avascular necrosis and chondrolysis. Avascular necrosis is uncommon with stable SCFE treated with pinning in situ.

There is a greater incidence of avascular necrosis associated with

unstable SCFE. A vigorous attempt at reduction of an unstable SCFE

should NOT be performed. Chondrolysis is a

gradual loss of the joint space following stabilization of the SCFE. It

has been associated with treatment with one or more pins as well as

with a spica cast in which no internal fixation was used.

-

|

|

Figure 5-3. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A: A 13-year-old boy with a severe, unstable left SCFE. B: Two cannulated screws were inserted for stabilization.

|

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Definition. A bacterial infection of the bone.

-

Etiology.

Bacterial seeding can occur through several methods: direct inoculation

(open fractures, penetrating wounds), local extension from adjacent

sites, or hematogenous spread from distant sites. Children are

skeletally immature and have physes at the ends of their long bones.

The metaphyseal region of the bone just below the physis is a frequent

location for osteomyelitis to occur. -

Presentation.

Patients may present with pain, limping, or refusal to walk or bear

weight on the affected lower extremity. Constitutional symptoms of

fever, malaise, and flu may or may not be present. One should inquire

about immunization status as well as history of recent illnesses [e.g.,

otitis media, chicken pox, strep pharyngitis, upper respiratory tract

illness (URTI)]. -

Physical examination.

Site of involvement may or may not be easy to identify, particularly in

younger patients. Careful palpation of entire extremity and the

metaphyseal regions in particular is important. All joints should be

placed through a range of motion. Inspect for areas of redness,

swelling, or warmth. -

Laboratory studies.

CBC with differential, ESR, CRP, and blood cultures are helpful in

making the diagnosis. The CRP has been recognized as a more rapidly

responsive test than the ESR, increasing more quickly early in the

evolution of the condition and declining more rapidly in response to

treatment. If the diagnosis remains unclear, consider other diagnostic

possibilities such as JRA, Lyme arthritis, and poststreptococcal

arthritis. -

Radiographic studies.

Plain radiographs of the affected area should be obtained. In

osteomyelitis they may frequently be normal for the first 7 to 14 days.

However, the radiographs may also be useful to rule out other

diagnostic possibilities. In patients with normal radiographs in whom

the diagnosis is still unclear, a technetium bone scan is a sensitive

test for acute osteomyelitis. It is particularly helpful in cases

involving the pelvis, proximal femur, and spine. MRI is also very

sensitive and has the added benefit of having greater soft-tissue

detail allowing assessment of marrow involvement, soft-tissue extension

or abscess formation, and presence of joint effusions. However, an MRI

may require significant sedation or anesthesia for younger patients. -

Aspiration.

In patients with an identified focus of infection, an attempt at

aspiration is recommended by many authors to identify the organism.

This may be done with sedation in the emergency department or the

fluoroscopic suite or, alternatively, under anesthesia in the operating

room. -

Organisms. On the basis of patient age:

-

Younger than 1 year old

-

Staphylococcus aureus

-

Group B Streptococcus

-

Escherichia coli

-

-

1 to 4 years old

-

S. aureus

-

Haemophilus influenzae

-

-

Older than 4 years old

-

S. aureus

-

-

Adolescent

-

S. aureus

-

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

-

-

-

Treatment.

Appropriate intravenous antibiotic based on culture or most likely

organism. Duration of antibiotic coverage is typically 6 weeks. After 2

to 3 weeks of IV treatment, the patient may be switched to oral

antibiotics if the following criteria are met: (a) the organism has

been identified, (b) there is

P.84

a

satisfactory oral antibiotic to which the organism is sensitive, (c)

the child will take the oral antibiotic, and (d) satisfactory serum

levels can be achieved with oral therapy (20). -

Surgical treatment.

If the patient does not respond to antibiotic treatment after the first

24 to 48 hours, consider the possibility of a subperiosteal or

intraosseous abscess as well as other diagnostic possibilities.

Consider surgical drainage of abscess or intramedullary canal if

necessary (21).

-

-

Septic arthritis (22)

-

Definition. An infectious arthritis of a joint, usually bacterial in nature.

-

Etiology.

Most frequently, it occurs as a result from adjacent osteomyelitis in

which the metaphyseal portion of the bone is intraarticular (e.g., hip,

shoulder, elbow, ankle). When pus from metaphysis decompresses itself

through cortex, joints can become infected. Infection is also possible

through hematogenous spread or direct inoculation. -

Joints most commonly involved: knee (41%), hip (23%), ankle (14%), elbow (12%), wrist (4%), and shoulder (4%).

-

Presentation.

Young children usually refuse to walk or bear weight on the lower

extremity. The child will usually be febrile and may show signs of

sepsis. If infection is in the upper extremity, children refuse to use

the affected extremity. Septic arthritis may also occur in the newborn

child; babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) may present

with pseudoparalysis of the affected limb with failure or refusal to

move it. -

Physical examination.

If the joint involved is superficial, classic signs of joint redness,

swelling, and warmth are present. However, if the joint is not

superficial (hip, shoulder), no visible abnormality may be detectable.

However, the patient will hold the affected limb in a position of

maximum comfort (e.g., keep the hip in flexion and external rotation).

Any attempt at passive range of motion is painful and restricted

because of guarding. -

Laboratory studies

include CBC with differential, ESR, CRP, and blood culture. The CRP and

ESR will become significantly elevated. The CBC may remain normal. -

Radiographic studies.

Plain radiographs of the affected joint should be obtained to look for

any evidence of bony destruction or erosions. For patients with

suspected hip pain, an ultrasound of the hip may confirm the presence

of a hip joint effusion. In some institutions, aspiration is performed

under ultrasound guidance. -

Joint aspiration

is mandatory to confirm the diagnosis. Joint fluid should be sent for

cell count, Gram stain, and culture and, if quantity permits, glucose

and total protein. If the patient is a teenager in whom gonococcal

infection is suspected, the laboratory should be notified in order to

perform cultures on chocolate agar in addition to the routine media.

The Gram stain may be positive for bacteria in only approximately 50%

of patients. The cell count most often has greater than 50,000 white

blood cells (WBCs) and/or greater than 90% polymorphonuclear

neutrophils (PMNs). -

Organisms. On the basis of patient age:

-

Younger than 1 year old

-

S. aureus

-

Group B Streptococcus

-

E. coli

-

-

1 to 4 years old

-

S. aureus

-

H. influenzae (less common now with H. influenzae B vaccination)

-

Group A Streptococcus

-

Streptococcus pneumoniae

-

-

Older than 4 years old

-

S. aureus

-

Group A Streptococcus

-

-

Adolescent

-

S. aureus

-

N. gonorrhoeae

-

-

Less common organisms include Kingella kingae, Salmonella, and Neisseria meningitidis.

P.85 -

-

Treatment. In

patients suspected of septic arthritis, treatment consists of surgical

incision and drainage of the affected joint. Surgical decompression of

the adjacent bone may also be indicated if there is evidence of an

intraosseous abscess. Intravenous antibiotics should be administered

once intraoperative cultures have been obtained. Empiric coverage

should be started initially based on the most likely organism involved.

Once culture and sensitivities have been identified, antibiotic

coverage can be tailored accordingly. The duration of antibiotics is

usually 4 to 6 weeks. An initial course of intravenous antibiotics is

followed by oral therapy until the patient’s symptoms and laboratory

studies have returned to normal.

-

-

Transient synovitis

-

Definition. An inflammatory, noninfectious process resulting in joint swelling and pain.

-

Presentation.

Transient synovitis most frequently occurs in young children aged 3 to

8 years. Patients often may have had a recent upper respiratory tract

illness or other viral illness in the 2 to 3 weeks before onset of

symptoms. Patients are usually afebrile with a history of several days

of pain or limping. The physician must differentiate between transient

synovitis and a truly infectious process such as septic arthritis or

osteomyelitis. -

Laboratory studies. CBC with differential, ESR, and CRP are usually within the normal range.

-

Radiographic studies.

Plain radiographs are usually normal or may show evidence of a joint

effusion. Ultrasound is helpful for confirming the presence of a joint

effusion. -

Aspiration.

Because the clinician is often confronted with having to exclude septic

arthritis, joint aspiration can be helpful in order to examine the

joint fluid. A Gram stain, cell count, and culture should be obtained.

The Gram stain should be negative and the cell count should have

between 5,000 and 15,000 WBCs with less than 25% PMNs. -

Treatment.

The primary treatment objective in the treatment of transient synovitis

is to ensure that septic arthritis has been excluded. Once septic

arthritis is excluded, then the condition can be treated expectantly

with reduction in activity, NSAIDs, and careful observation (23).

-

-

Evaluation of the patient with back pain

-

History

-

Location of pain (neck/thoracic/lumbar)

-

Radiation of pain into lower extremities

-

Associated symptoms such as numbness, tingling, weakness, change in bowel or bladder function, pain at night, etc.

-

Onset of pain (acute/gradual)

-

Frequency and duration of symptoms

-

Any improvement with NSAIDs/aspirin

-

Is patient involved in athletic

activities that are associated with repetitive hyperextension of back

such as figure skating, gymnastics, dance, football (particularly

lineman) or hockey?

-

-

Physical exam. Have patient dressed in examination gown or other appropriate clothing.

-

Back ROM: flexion/extension/side bending/rotation

-

Pain with palpation along spine

-

Radicular pain associated with straight-leg test

-

Complete neurologic exam including:

-

Adam’s forward bending test (see below)

-

Hip ROM: possible referred pain from hip pathology

-

-

Radiologic tests.

If pediatric patient describes significant back pain and/or any

abnormal findings are present on physical exam, it is appropriate to

obtain plain radiographs.-

AP and lateral radiograph of thoracic and

lumbar spine if pain is localized to thoracic or thoracolumbar region

or any findings to suggest scoliosis. -

AP/lateral and oblique images of lumbar

spine if patient localizes pain to lumbar region of back or pain

radiates into lower extremities. -

Evaluate radiographs for signs of:

-

Scoliosis

-

Spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis

-

Loss of disc space

-

Vertebral end-plate changes (erosions, Schmorl nodes)

-

Other bony changes (absent pedicle, curvature without rotation, etc.)

-

-

-

Additional imaging tests.

If neurologic abnormalities are identified on physical exam, consider

MRI of spinal canal. If no neurologic findings are present but pain

presentation is worrisome for underlying bone tumor or structural

abnormality, consider three-phase nuclear medicine bone scan. -

Differential diagnosis

-

Mechanical low-back pain

-

Spondylolysis/Spondylolisthesis

-

Discitis

-

Lumbar Scheuermann disease

-

Herniated intervertebral disc

-

Spine-related bone tumors

-

-

Mechanical low-back pain

-

Definition: back pain usually localized

to the lower back without radiation to lower extremities and without

neurologic findings on physical exam or radiographic abnormalities.

Previously thought to be rare in children, it remains less common in

children than in adults but can be a source of back pain if other

causes have been excluded. Symptoms most often occur after sitting for

long periods of time, tend to be vague or non-specific, and occur

sporadically. -

Physical exam: notable for lack of abnormal findings.

-

Radiographic exam: plain radiographs are

normal. No specialized radiographic studies are recommended at the time

of the initial evaluation. -

Treatment:

-

Referral to physical therapy for home-based exercise program of back strengthening and posture retraining.

-

Prescription for NSAIDs.

-

Return to clinic in 1 to 2 months for follow-up. If symptoms not improved or have changed, reconsider diagnosis.

-

-

-

Spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis.

-

Spondylolysis:

a structural defect in the bone in the posterior elements of the spine.

Most often in the “pars interarticularlis” region of the L5 vertebra.

Associated with hyper-extension activities such as dance, gymnastics,

figure skating; presents as low-lumbar back pain without radiation into

the lower extremities but exacerbated by hyperextension activities. -

Spondylolisthesis:

a translation or slippage of one vertebra on the next lower vertebra.

The most common cause in children is an “isthmic spondylolisthesis” in

which a lesion or defect in the pars interarticularis permits forward

slippage of the superior vertebra.

-

-

Discitis. A

condition in which children develop back pain that arises from a

presumed bacterial infection of the intervertebral disc. They may

present

P.87

with

gradual onset of pain, loss of lumbar lordosis, and progressive decline

in activity level potentially to the point of refusing to walk. The

child may remain afebrile. Current theories of etiology suggest it may

start as a vertebral osteomyelitis that spreads to the adjacent disc

space. If suspected, laboratory tests should be obtained including CBC

with differential, ESR, CRP, and blood cultures. The CBC may be normal

but some elevation of the ESR and CRP is frequently present. Initial

radiographs may be normal or may show vertebral end-plate

irregularities. Later radiographs may show a narrowing of the disc

space involved. The diagnosis may be confirmed with specialized imaging

tests such as nuclear medicine bone scan, CT, or MRI. Treatment

consists of antibiotic therapy and, when appropriate, back

immobilization with a removable spinal orthosis for symptomatic support. -

Lumbar Scheuermann disease.

A condition in which patients present with lumbar back pain without

radicular symptoms. There are end-plate changes termed “Schmorl nodes”

in the lumbar vertebra on plain radiographs. In contrast to

Scheuermann’s disease of the thoracic spine (see below), which is

associated with significant thoracic kyphosis and vertebral wedging,

these changes are not found in the lumbar spine. -

Herniated intervertebral disc.

A herniation of the central portion of the disc, the “nucleus

pulposus,” into the spinal canal. Occurs in adolescent and teenage

patients. Symptoms usually have an acute, specific onset and are

associated with radicular symptoms of pain radiating down into the

lower extremity. Neurologic exam is helpful to look for signs of motor

weakness. An avulsion fracture of the vertebral ring apophysis

may also present with sudden onset of back pain with radicular-type

symptoms radiating into the lower extremities. This may be visible on

plain films as a small triangular fragment of bone displaced from the

lower end plate of the vertebra. If a herniated disc or a vertebral

ring apophysis avulsion-type fracture is suspected, an MRI scan can

help confirm diagnosis. -

Bone tumors involving the spine.

There are a number of bone tumors that may arise from the vertebral

body or the posterior elements of the spine. They may present with

pain, particularly night pain, deformity, or other associated symptoms.

Physical exam may reveal findings of scoliosis, however, radiographs

may reveal a curvature of the spine without any rotational component

present. This suggests that the curvature is postural, due to the

painful process, rather than a structural, scoliosis-type curve. Benign

tumors that arise in the spine most frequently include osteoid osteoma,

osteoblastoma, and hemangioma. Primary malignant tumors of the bone

that arise in the spine are relatively rare.

-

-

Idiopathic adolescent scoliosis

-

Definition. A

deformity of the spine consisting of a lateral curvature measuring

greater than 10 degrees on a spine radiograph that also has a

rotational component. The word “idiopathic” suggests no identifiable,

underlying cause. There may be a genetic component. -

Presentation.

Most often patients are adolescent girls who have been detected either

on school screening examination or by an observant primary physician.

Boys are affected less often and have a lower incidence of progressive

curves. The deformity may occasionally be seen in younger children.

Family history is frequently positive. Idiopathic scoliosis should be painless.

The examiner should inquire about any neurologic symptoms including

weakness, numbness, radicular symptoms, or bowel or bladder changes. -

Incidence.

For curves greater than 10 degrees, the overall incidence is 2%.

However, for curves measuring greater than 20 degrees and requiring

treatment, the incidence is 0.2%. -

Physical examination. All patients should be examined in a gown so that the back can be well visualized. Inspect pelvic height for evidence of limb

P.88

length difference. Examine shoulder height and trunk position for

evidence of asymmetry or truncal imbalance. With the patient standing,

have the patient bend forward at the waist. Observe the patient’s back

for evidence of rib hump deformity. This is the Adam forward bending test.

Finally, complete a thorough neurologic examination, including

abdominal reflexes and tests for long tract or upper motor neuron

lesions. -

Radiographic evaluation.

PA and lateral spine radiographs on a long cassette to include the

thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions of the spine. The curvature of the

spine can be measured using the COBB method. -

Characteristics. For true idiopathic scoliosis, the curve is most often:

-

Painless

-

Convex to the right in the thoracic spine

-

Not associated with any neurologic changesIf a curve does not fit this pattern, one must exclude

other possible causes. If the curve is convex to the left, painful, has

associated neurologic changes, or is rapidly progressive, one should

consider obtaining an MRI scan in order to rule out possible underlying

spinal cord abnormalities such as syringomyelia, tethered cord,

diastematomyelia, or spinal cord tumor.

-

-

Risk factors for progression

include young age, female gender, prepubertal status, and curve greater

than 11 degrees. The spine curve is at greatest risk for progression

during periods of accelerated skeletal growth (24). -

The goal of treatment is to prevent further progression of the curve.

-

Treatment of

idiopathic scoliosis depends on the size of the curve as well as the

age of the patient at the time of detection. Typically, for curves

greater than 11 degrees and less than 20 degrees, treatment consists of

observation with repeat spine radiographs

obtained in 4 to 6 months. The younger the child at the time of curve

detection, the greater the risk for future progression of the curve. If

the curve is greater than 20 to 25 degrees in a skeletally immature

patient, brace treatment is indicated.

Brace treatment is most effective in moderate-sized and flexible curves

in growing adolescent patients. The goal of brace treatment is to

arrest any further progression of the curve. For patients in whom a

large curve of greater than 45 to 50 degrees is already present or for

whom the curve progresses despite brace treatment, treatment is surgical spinal fusion with instrumentation.

-

-

Kyphosis

-

Definition.

An increased curvature of the thoracic spine in the sagittal plane,

either from the side or on the lateral radiograph, producing a

rounded-back appearance. -

Characteristics. Normal thoracic kyphosis is 20 to 45 degrees. Scheuermann disease

is a condition in which the thoracic curve on the lateral radiograph is

greater than 45 degrees and associated with wedging of three adjacent

central vertebral bodies of 5 degrees or more. It may be associated

with end-plate changes of the vertebral bodies such as Schmorl nodes.

It should be distinguished from postural kyphosis, in which the

vertebral bodies do not exhibit changes and the curvature resolves with

improvement of the patient’s posture. -

Presentation. Patients usually have one of two complaints: pain or concerns regarding appearance.

-

Physical examination.

Careful examination of the back with the patient standing, on forward

bending, and with hyperextension in the prone position can help

determine the flexibility of the kyphosis. Increased thoracic kyphosis

is frequently associated with increased lumbar lordosis. The

possibility of hip flexion contractures should be assessed. A careful

neurologic examination should also be performed. -

Radiographs. Standing PA and lateral thoracolumbar spine radiographs should be obtained.

-

Treatment.

Options include observation, bracing, and surgery. For patients who are

asymptomatic with a relatively small curve, one may consider

P.89

continued

observation. For symptomatic patients who are skeletally immature with

curves greater than 45 to 50 degrees, one may consider brace treatment.

The indications for surgical treatment include kyphosis greater than 70

degrees, progressive deformity, recalcitrant pain, and concerns

regarding patient appearance in the setting of significant deformity (25).

-

-

Lordosis

-

Definition. An increase in “swayback” appearance of the lower lumbar spine.

-

Presentation. The patient may complain of low back pain, concern regarding appearance, or both.

-

Etiology.

Possible causes include posture (especially in younger patients),

bilateral congenital dislocation of the hip, hip flexion contracture,

hamstring weakness, increased thoracic kyphosis,

spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, and congenital spinal deformity. -

Physical examination

should include careful evaluation of the back, hips, and lower

extremities and should also include a thorough neurologic evaluation. -

Radiographs. PA and lateral thoracolumbar spine radiographs should be obtained.

-

Treatment.

Careful exclusion of underlying abnormalities should be undertaken. If

other underlying causes have been excluded and the cause is thought to

be postural, then treatment may consist of further observation.

-

-

Cerebral palsy (26,27)

-

Definition. A

nonprogressive disorder resulting from an injury to the brain, usually

within the first year of life, and resulting in impairment in motor

function. -

Classification can be geographic (part of body most affected) or by type of motor dysfunction.

-

Geographic

-

Hemiplegia. Arm and leg on one side only affected

-

Diplegia. Major spasticity in lower limbs, less in upper

-

Triplegia. Three-limb involvement

-

Quadriplegia. All four limbs, “total body involved”

-

-

Motor type

-

Spastic. Increased stretch reflexes (pyramidal)

-

Athetoid. Fluctuating motor tone, often with spontaneous, involuntary rhythmic motor movements (extrapyramidal)

-

Dystonia. Similar to athetoid; intermittent or inconsistent tone

-

Mixed. A combination of spasticity and dystonia

-

-

-

Causes

-

Prenatal.

Intrauterine infection, for example, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella,

cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex), genetic or chromosomal

abnormalities -

Perinatal. Premature birth, low birth weight, asphyxia, erythroblastosis fetalis

-

Postnatal. Infection, stroke, cardiac arrest, near drowning

-

-

Hierarchical approach to problems

-

Primary problems include abnormal muscle tone, poor selective muscle control, and poor balance.

-

Secondary problems

include muscle and joint contractures and bony deformities (increased

femoral anteversion, tibial torsion, and foot deformities). -

Tertiary problems include compensatory mechanisms for primary and secondary problems.

-

-

Treatment

-

Physical therapy

-

Orthotics

-

Assistive devices: wheelchair, walker, crutches

-

Tone-reducing agents or medications: oral (e.g., baclofen, Valium, dantrolene) or focal (e.g., Botox, phenol)

-

Neurosurgical options: selective dorsal rhizotomy, intrathecal baclofen pump

-

Orthopaedic surgery: soft-tissue lengthening procedures, bony realignment procedures

P.90 -

-

Nonambulatory patients.