Scoliosis

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Scoliosis

Scoliosis

Paul D. Sponseller MD

Description

-

Scoliosis is a 3D curvature of the spine, best appreciated on an AP radiograph and physical examination.

-

Both thoracic and lumbar segments of the spine may be affected.

-

It is defined as a curve >10°.

-

Classification (1–3):

-

Etiology:

-

Idiopathic

-

Congenital

-

Neuromuscular

-

Connective tissue

-

Degenerative

-

-

Location (of the apex or middle of the curve):

-

Thoracic

-

Thoracolumbar

-

Lumbar

-

-

Subclassification of idiopathic scoliosis by age:

-

Infantile (<3 years)

-

Juvenile (3–10 years)

-

Adolescent (≥11 years)

-

-

Epidemiology

-

The most common type is idiopathic scoliosis.

-

Scoliosis may occur at any age.

-

The most common age at diagnosis of idiopathic scoliosis is 11–13 years (3).

Prevalence

-

Small curves of idiopathic scoliosis are almost equally prevalent in males and females.

-

Females, however, are 3–4 times more likely to develop progression of the curve.

-

In scoliosis other than the idiopathic type, less difference in gender-related prevalence is noted.

-

Prevalence of curves >10° is ~2–3% (3).

-

Prevalence of curves requiring bracing (>25°) is ~0.3% (3).

-

Prevalence of curves requiring surgery is ~1 in 1,000 (3).

Risk Factors

-

Progressive idiopathic scoliosis

-

Positive family history

-

Female gender

-

Premenarchal status

-

Paralytic scoliosis

-

Severe spinal cord injury before adolescence

-

Scoliosis in cerebral palsy, including total involvement

Genetics

Idiopathic scoliosis is transmitted as autosomal dominant, with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity.

Etiology

-

Idiopathic scoliosis:

-

Theories about the cause of idiopathic scoliosis include a subtle connective-tissue abnormality or neurohormonal defect.

-

Causes of congenital scoliosis include hemivertebrae and fusions between vertebrae.

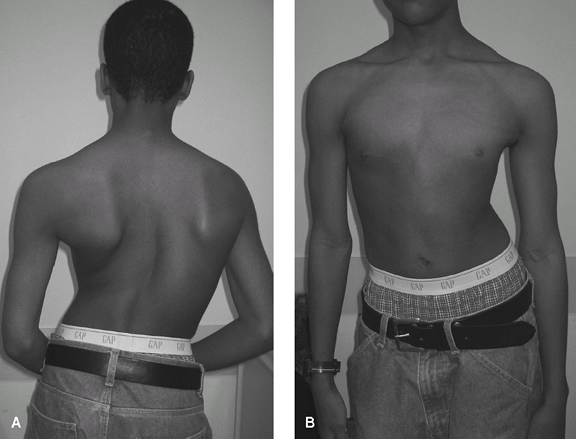

Fig. 1. Clinical appearance of severe scoliosis. A: Posterior view. B: Anterior view.

Fig. 1. Clinical appearance of severe scoliosis. A: Posterior view. B: Anterior view.

-

-

Neuromuscular scoliosis:

-

Cerebral palsy

-

Traumatic paralysis

-

Spina bifida

-

Poliomyelitis

-

Friedreich ataxia

-

Virtually any systemic neurologic condition that affects the trunk

-

-

Connective tissue-associated scoliosis:

-

Marfan syndrome

-

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

-

NF

-

Down syndrome

-

Associated Conditions

-

Almost any systemic neurologic disorder that affects the trunk

-

Most connective-tissue disorders

Signs and Symptoms

-

Varied, depending on the location of the spine affected (Fig. 1)

-

For thoracic curves, the ribs are rotated

on the convex side, producing a “rib hump” and a more prominent scapula

on the same side. -

With thoracolumbar and lumbar curves, 1 side of the pelvis becomes more prominent, giving the appearance of a “high hip.”

-

Many, but not all, teens develop increased pain in the area of the curve.

-

Symptoms are few until adulthood, when back pain and nerve root pain may develop.

P.373

Physical Exam

-

Examine the patient, while he or she is standing, to see shoulder, rib, and hip asymmetry.

-

Measure leg lengths.

-

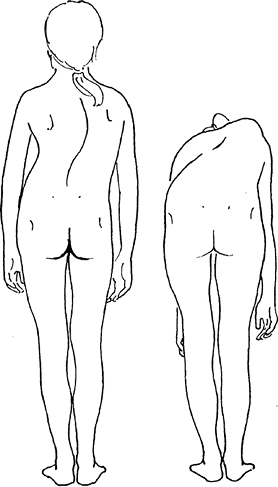

Perform the forward bend test with the

patient’s legs straight and observe the entire spine for asymmetry

between the right and left sides (Fig. 2).-

This test is most useful and highly sensitive, and it is used in school screening programs.

-

If asymmetry is present, measure the slope between the right and left sides of the rib cage.

-

Some patients with a positive forward bend test do not have severe scoliosis.

-

Follow-up a positive test with a radiograph if the rib slope is >6°.

-

Repeat the test if an abnormality is found.

-

-

Quantify rib prominence or a hump by a scoliometer.

-

Observe any kyphosis and lordosis.

-

Inspect the skin over the entire spine

for dimples, hair, or vascular markings, which may signal an underlying

congenital anomaly. -

Rule out ligamentous laxity.

-

Examine for café-au-lait spots or neurofibromas.

-

Perform a careful neurologic examination,

which can be practically done by observing gait and 1-legged hop and by

testing reflexes. -

Assess the patient’s physical maturity by

checking for secondary sexual characteristics such as axillary and

facial hair, skin changes, breast development. -

Measure the height for serial comparison.

Fig. 2. The forward bend test exaggerates the rib deformity in scoliosis and allows sensitive diagnosis.

Fig. 2. The forward bend test exaggerates the rib deformity in scoliosis and allows sensitive diagnosis.

Tests

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

Standing posteroanterior radiography of the entire spine is indicated.

-

Lateral films should be obtained if associated abnormal kyphosis is present.

-

Spine films usually show the iliac crests and allow determination of the Risser stage (3) for skeletal maturity.

-

The Risser stage is the amount of ossification of the iliac growth cartilage.

-

Risser 0, unossified, skeletally immature; Risser V, fully ossified, mature.

-

-

Presence of an open triradiate cartilage of the hip indicates that the growth spurt has not been completed.

-

-

MRI is indicated only if spinal cord disease is possible.

Pathological Findings

-

The vertebrae are rotated toward the convexity of the curve.

-

In addition, individual vertebrae are misshapen because of growth while curved.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Isolated rib rotation may occur without scoliosis.

-

Kyphosis (a curvature in the sagittal

plane only, which may be confused with scoliosis), clavicle fracture,

or Sprengel deformity may give the appearance of a “high shoulder.” -

Leg-length inequality may cause the appearance of a “high hip.”

General Measures

-

The spine in patients with scoliosis is not unstable.

-

Encourage patients to be as active as possible.

-

Physical therapy and exercise if pain or stiffness is present

-

Patients with minor curves (<25°)

should be observed if they are still growing, but they can be

discharged if skeletal maturity has been reached. -

Patients with moderate curves (25–40°) should be braced if substantial growth remains.

-

Patients with large curves (>45°):

-

See an orthopaedic surgeon to determine whether correction is indicated.

-

Surgery offered.

-

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

-

Strengthening and stretching of abdominal and extensor muscles if pain exists

-

Not indicated for routine cases of scoliosis

-

Does not help correct the curves

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Yoga may be helpful for back discomfort.

P.374

Surgery

-

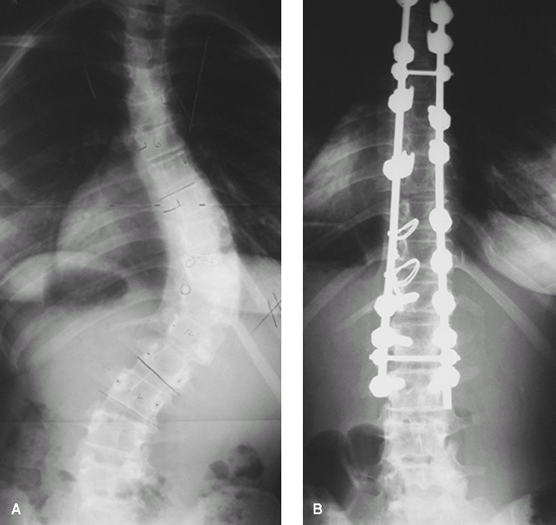

If a curve is to be fused, 1 or 2 rods (Fig. 3) are used to correct the curve, and a bone graft is placed along the rod to cause the vertebrae to fuse.

-

Only the curved region is fused.

-

The neurologic risk is currently <1% (2).

-

Patients should be followed at least until maturity.

Prognosis

-

Pulmonary compromise, including cor

pulmonale in congenital or neuromuscular curves, occurs mainly in

patients with curves >100° (4). -

Most untreated curves >40–50° in adulthood slowly become worse (3).

Fig. 3. Patient with severe scoliosis before (A) and after (B) posterior instrumentation and fusion.

Fig. 3. Patient with severe scoliosis before (A) and after (B) posterior instrumentation and fusion.

Complications

-

Severe curves (>70°) occasionally may progress to the point where they compromise pulmonary function.

-

Curves >40° pose an increased risk of back pain in adulthood (3).

-

Surgical complications include neurologic injury (<1%), infection, and failure of the vertebrae to fuse (3).

Patient Monitoring

-

Growing children should be seen every 4–6 months, usually with radiographs.

-

Adults should be seen every 1–5 years.

-

Patients with congenital scoliosis should be monitored for associated anomalies.

References

1. Hedequist D, Emans J. Congenital scoliosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:266–275.

2. Lenke

LG, Edwards CC, II, Bridwell KH.The Lenke classification of adolescent

idiopathic scoliosis: How it organizes curve patterns AS a template to

perform selective fusions of the spine. Spine 2003;28:S199–S207.

LG, Edwards CC, II, Bridwell KH.The Lenke classification of adolescent

idiopathic scoliosis: How it organizes curve patterns AS a template to

perform selective fusions of the spine. Spine 2003;28:S199–S207.

3. Newton PO, Wenger DR.Idiopathic scoliosis. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, eds. Lovell and Winter’s Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:693–762.

4. Weinstein

SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Health and function of patients with

untreated idiopathic scoliosis: A 50-year natural history study. JAMA 2003;289:559–567.

SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Health and function of patients with

untreated idiopathic scoliosis: A 50-year natural history study. JAMA 2003;289:559–567.

P.375

Codes

ICD9-CM

-

737.30 Idiopathic scoliosis

-

754.2 Congenital scoliosis

Patient Teaching

-

Instruct patients in the general guidelines and treatment options.

-

Remind parents of the genetic nature of

the condition so that relatives and young siblings with scoliosis may

be detected while bracing is still an option.

Prevention

-

Curve worsening may be effectively prevented in growing children by use of a brace.

-

It must be worn 18–23 hours per day.

-

This intervention is effective in ~75% of patients (2).

-

Bracing does not correct curves.

-

FAQ

Q: What is the cause of scoliosis?

A: It is not known. It often is passed along in families. It may be a subtle disorder of balance or spinal growth.

Q: Can physical therapy or exercises slow or halt the worsening of the curve?

A: No evidence suggests that it can.

Q: Can bracing correct scoliosis?

A: It rarely produces any permanent correction.

Q: Does scoliosis affect internal organs?

A:

It is associated with decreased pulmonary function in curves ≥70°.

There is little documentation of effects on cardiac, gastrointestinal,

or genitourinary function.

It is associated with decreased pulmonary function in curves ≥70°.

There is little documentation of effects on cardiac, gastrointestinal,

or genitourinary function.