Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Primary Osteoarthritis

IV – Elbow Reconstruction > Part C – Operative Treatment Methods

> 60 – Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Primary Osteoarthritis

It occurs in less than 2% of the population and principally affects the

dominant extremity in middle-age manual laborers. It has also been

reported in people who require continuous use of a wheelchair or

crutches, athletes, and in patients with a history of osteochondritis

dissecans of the elbow. It has different pathologic changes than the

age-related changes of the distal humerus and the radiohumeral joint.

of patients with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow, the treatment

options are more limited and the role of total elbow arthroplasty is

less defined in this population of patients.

more advanced in the radiohumeral joint, where bare bone is often in

wide contact and the capitellum appears to have been shaved obliquely (Fig. 60-1).

This is owing to the high axial, shearing, and rotational stresses at

this articulation, which result in marked erosion of the capitellum and

callus hypertrophy formation in a skirtlike pattern on the radial neck.

beginning of the disease process and becomes more pronounced with more

advanced disease. The central aspect of the ulnohumeral joint is

characteristically spared. The anterior and posterior involvement of

this joint is usually manifested by fibrosis of the anterior capsule in

the form of cordlike band and hypertrophy of the olecranon.

(especially medially), the coronoid process, and the coronoid fossa.

These changes in the radiohumeral and ulnohumeral joints lead to the

loss and fragmentation of the cartilaginous joint surfaces with

distortion, cyst formation, and bone sclerosis. Kashiwagi noted that

the early stage of the disease is characterized by small, round bony

protuberances that progress into various shapes of osteophytes and bony

sclerosis with more advanced cases.

patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow report minimal symptoms. This

is partly related to the fact that the elbow is a slight weight-bearing

joint compared with the lower extremity joints.

intra-articular loose bodies, pain at the end points of the arc of

motion (flexion or extension), and progressive loss of range of motion

are characteristic manifestations of osteoarthritis of the elbow. In

athletes who are required to hyperextend their elbows, pain can be

significant and limits their performance.

pain with forearm rotation and throughout the range of elbow motion.

This could lead to disability in this patient population as well as in

the older laborers who extensively use their upper extremity.

osteoarthritis of the elbow might be the first manifestation of ulnar

neuropathy. It is reported that ≤20% of patients with primary

osteoarthritis of the elbow have some degree of ulnar neuropathy. The

proximity of the ulnar nerve to the arthritic posteromedial aspect of

the ulnohumeral joint makes it susceptible to impingement. The

expansion of the capsule as a result of synovitis and the presence of

osteophytes in that area of the joint result in direct compression and

ischemia of the ulnar nerve. Acute onset of

cubital

tunnel syndrome in patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow might be

also the first manifestation of medial elbow ganglion.

|

|

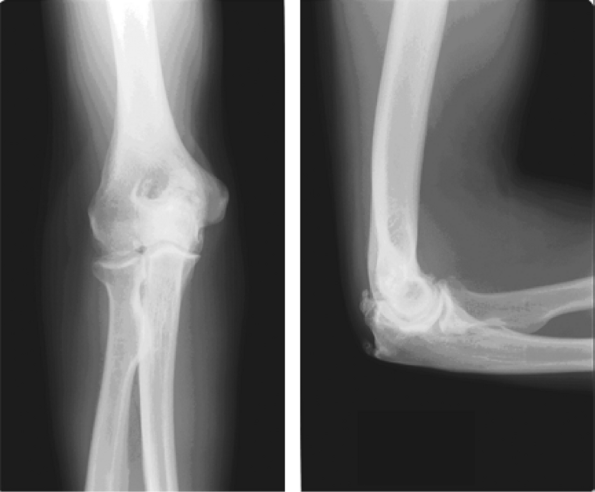

Figure 60-1

A lateral view of the right elbow, showing advanced osteoarthritis specifically involving the radiocapitellar joint. Notice the formation of osteophytes anteriorly and posteriorly. |

anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the elbow include

radiocapitellar narrowing, ossification, and osteophyte formation in

the olecranon fossa in almost all patients with osteoarthritis of the

elbow. Loose bodies and fluffy densities might be observed filling the

coronoid and olecranon fossae (Fig. 60-2).

detailed structural anatomy of the articular surface of the elbow with

an accurate determination of the locations of the osteophytes and loose

bodies. When contemplating surgical treatment of the osteoarthritic

elbow, a CT is quite helpful for determining which osteophytes need to

be removed. Radiographs do not allow for accurate visualization of all

osteophytes.

osteoarthritis of the elbow, most of these patients tend to be active

and involved in manual labor work, which will place a great demand on

any kind of prosthetic replacement. All limited operative debridement

options should be exhausted before contemplating elbow replacement in

this group of patients.

nonsurgical measures should be followed. This consists of activity

modification, physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and

possibly steroid injection. As in other joints arthritis, if there is

no improvement with these symptomatic measures, operative management is

warranted.

intra-articular loose bodies and is effective in relieving the

patient’s mechanical symptoms of catching and locking. Elbow

arthroscopy has proved quite effective in removing osteophytes and

releasing tight areas of capsule in the arthritic elbow. Surgeons with

significant experience in elbow arthroscopy can remove all restricted

capsule and reach all areas of the anterior and posterior elbow joint

and areas of impinging osteophytes. To release a similar amount of the

elbow joint with an open approach would require a wide exposure.

described by Outerbridge, which consisted of decompression of the

ulnohumeral joint with resection of the coronoid and olecranon

osteophytes and fenestration of the distal part of the humerus. A

disadvantage of this technique is the difficulty in exposing and

excising the osteophytes in the radial head fossa.

arthroscopic debridement involving capsular release, fenestration of

the distal part of the humerus, and removal of osteophytes. Also,

Morrey reported good results with open ulnohumeral arthroplasty, a

variation of the original technique in which a trephine is used to

remove the osteophytes encroaching on the olecranon and coronoid fossae.

symptoms, then total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) may cautiously be

considered as the next alternative of treatment. Most studies in the

literature reporting on total elbow arthroplasty involve large numbers

of patients, mostly with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory

pathologies, but very few patients with primary osteoarthritis. This

makes it difficult to make accurate conclusions on the value of this

treatment option for this population of patients. There are few studies

in the English literature reporting specifically on the

outcome and complications of TEA as a treatment option for patients with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow.

|

|

Figure 60-2

An anterior-posterior and lateral view of a right osteoarthritic elbow showing narrowing of the joint line and subchondral sclerosis, with formation of osteophytes in the coronoid, capitellar, and olecranon fossae. |

Over a 13-year period, only 5 out of 493 patients (<1%) who

underwent TEA had the procedure performed for primary osteoarthritis of

the elbow. The Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) cemented

semiconstrained prosthesis was used in three patients, and the

Pritchard elbow-resurfacing system (ERS) (De Puy, Warsaw, IN) cemented

unconstrained prosthesis was used in the other two patients. The

average age of the patients was 67 years, and a follow-up ranged from

37 to 121 months. Two minor and four major complications were reported

in four elbows, two of which required revision. This rate of

complications according to the authors is much higher than the rate of

complication reported in TEA performed for other reasons in the same

institution during the same period of time, including revision TEA,

posttraumatic arthritis, nonunion of distal humerus, and rheumatoid

arthritis.

unlinked primary total elbow arthroplasties in 10 patients with

osteoarthritis of the elbow. The diagnosis was primary osteoarthritis

of the elbow in nine patients and posttraumatic osteoarthritis in two

patients. The average age of the patients was 66 years, with a mean

follow-up of 68 months. Only one patient required revision after 97

months for ulnar component loosening. All patients reported good

symptomatic relief of pain and a significant increase in range of

motion, and all patients considered the procedure to be successful.

Souter-Strathclyde total elbow arthroplasty used in patients with

rheumatoid arthritis. The revision rate in their series (9%) performed

for ulnar component loosening compares favorably with the revision rate

with the rheumatoid patients (5% to 21%), in which the main indications

for revision included dislocation and perioperative fracture. The

authors attributed the decrease in the incidence of perioperative and

postoperative fracture to the good amount of bone stock in patients

with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow that makes the risk of

fracture very minimal.

in patients with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow are very limited.

The above-mentioned studies included small numbers of patients, and no

final recommendation could be drawn at this time.

anatomy and kinematics will lead to advances in prosthetic design and

surgical technique. The newer anatomic unlinked implants may improve

the outcome of elbow replacement in younger patients. More outcome

studies are needed on these implants or any other modern implants

before openly recommending elbow replacement in younger active patients

with primary osteoarthritis of the elbow.

SA, Morrey BF, Adams RA, et al. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary

degenerative arthritis of the elbow: long-term outcome and

complications. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:2168–2173.

MP, Black DL, Clark DI, et al. Early results of the Souter-Strathclyde

unlinked total elbow arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85B:351–353.

D. Osteoarthritis of the elbow joint: intra-articular changes and the

special operative procedure, Outerbridge-Kashiwagi method (O-K method).

In: Kashiwagi D, ed. Elbow Joint. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1985:177–188.

H, Hirayama T, Minami A, et al. Cubital tunnel syndrome associated with

medial elbow ganglia and osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:1413–1419.

IA, Nuttal D, Stanley JK. Survivorship and radiological analysis of the

standard Souter-Strathclyde total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81B:80–84.

K, Mizuseki T. Debridement arthroplasty for advanced primary

osteoarthritis of the elbow. Results of a new technique used for 29

elbows. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:641–646.