The Tibia and Fibula

but are different in structure and function. The tibia is large,

transmits most of the stress of walking, and has a broad, accessible

subcutaneous surface. The fibula is slender and plays an important role

in ankle stability as well as taking one sixth of the load. It is

surrounded by muscles, except at its ends. Surgical approaches to the

fibula are more complex than are those to the tibia, because of both

the depth of the bone and the presence of the common peroneal nerve,

which winds around its upper third.

is rarely used but can save the limb when skin breakdown has made

anterior approaches impossible. This approach is commonly used for bone

grafting for nonunited fractures.

the tibial plateau. The anterolateral and posteromedial approaches are

often used together to treat complex proximal tibial fractures. The

minimal access anterolateral approach to the tibial plateau utilizes

two windows of the anterolateral approach.

for percutaneous plating of multifragmentary fractures of the distal

tibial metaphysis.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the lateral tibial plateau

-

Bone grafting for delayed union and nonunion of fractures

-

Treatment of osteomyelitis

-

Excision and biopsy of tumors

-

Proximal tibial osteotomy

-

Harvesting of bone graft

and delicate, consisting of skin and underlying fascia only. Problems

with soft tissue in this area are frequent and massive swelling or

blistering can occur, particularly following high-velocity trauma.

Careful assessment of the soft tissues is critical before surgery, and

definitive treatment of fractures in this area is frequently delayed to

allow swelling to subside and the soft tissues to recover. The

anterolateral approach is preferred to a direct anterior approach to

the tibia because the skin in the anterolateral approach does not

directly overlay the bone.

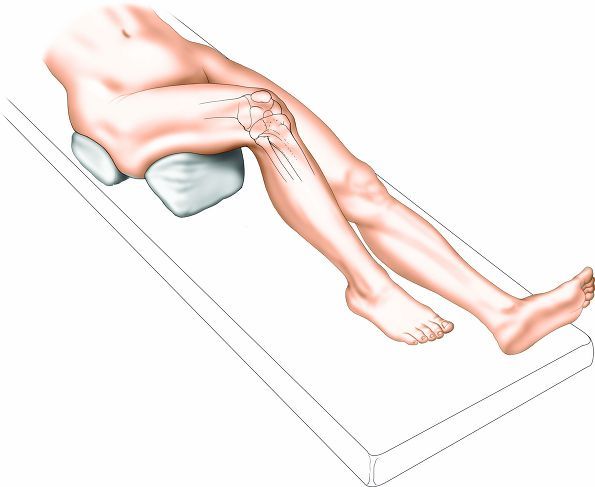

Place a small bag underneath the buttock to correct the normal external

rotation of the lower limb. This will ensure that the patella is facing

directly anteriorly. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevating it for 3

to 5 minutes or by applying a soft rubber bandage. Then inflate a

tourniquet.

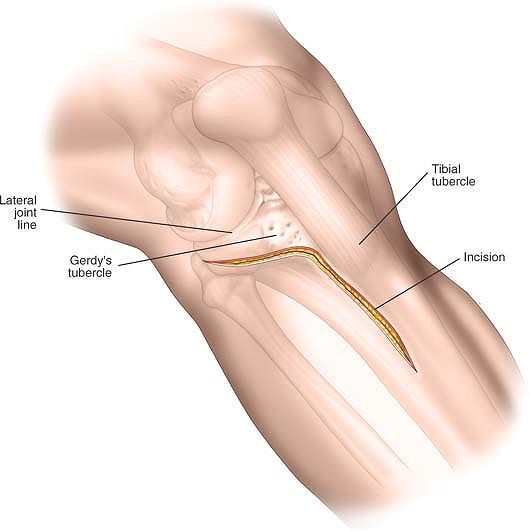

anterior border. Identify the position of the lateral joint line of the

knee by flexing and extending the joint. Palpate Gerdy’s tubercle just

lateral to the patella tendon. All these landmarks are easily palpable,

even in an obese patient.

proximal to the joint line, staying just lateral to the border of the

patella tendon. Curve the incision anteriorly over Gerdy’s tubercle and

then extend it distally, staying about 1 cm lateral to the anterior

border of the tibia (Fig. 11-2). The exact length of the incision depends on the pathology to be treated and the implant to be used.

dissection is essentially epi-periosteal and does not disturb the nerve

supply to the extensor compartment.

|

|

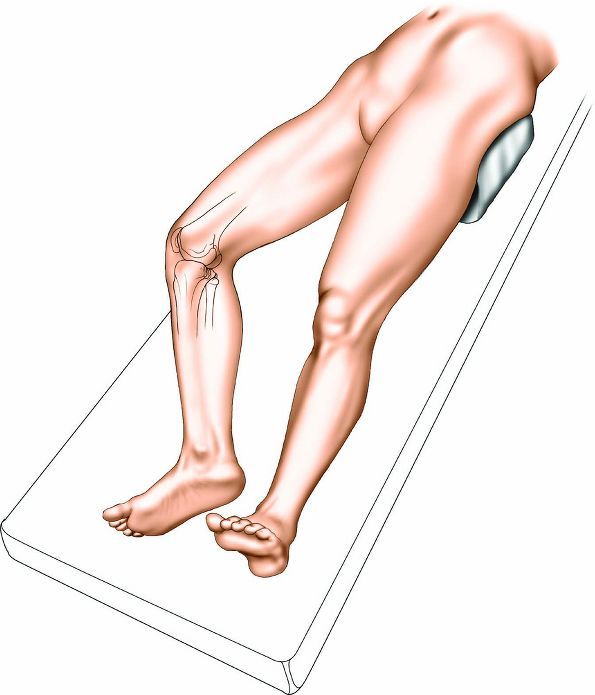

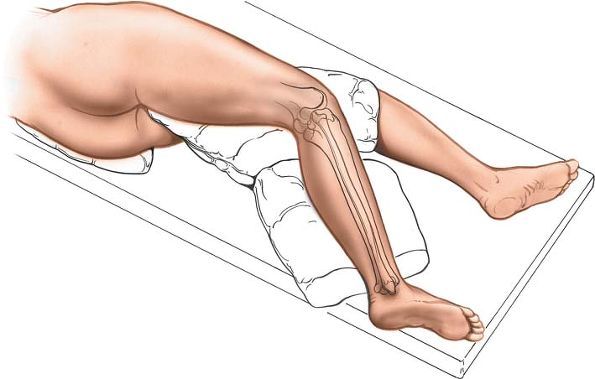

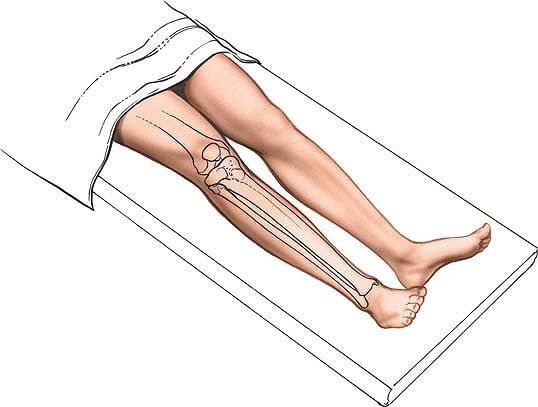

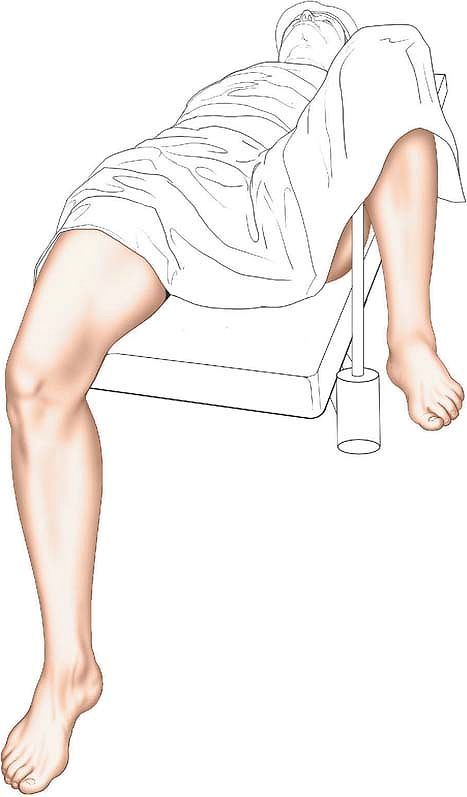

Figure 11-1 Place the patient supine on a radiolucent table, with a firm wedge beneath the knee to flex the joint to approximately 60°.

|

|

|

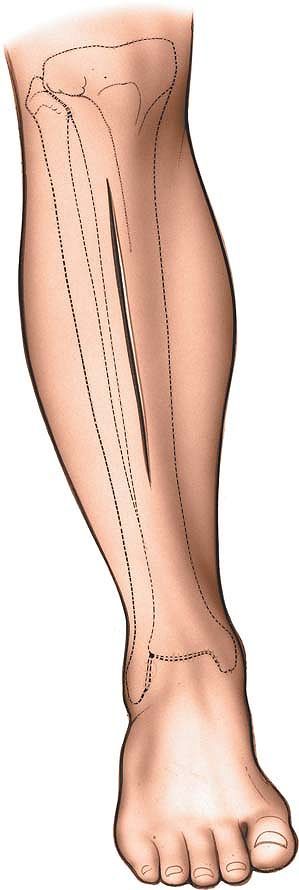

Figure 11-2

Make an S-shaped incision. Start approximately 3 to 5 cm proximal to the joint line, staying just lateral to the border of the patella tendon. Curve the incision anteriorly over Gerdy’s tubercle and extend it distally, staying about 1 cm lateral to the anterior border of the tibia. |

|

|

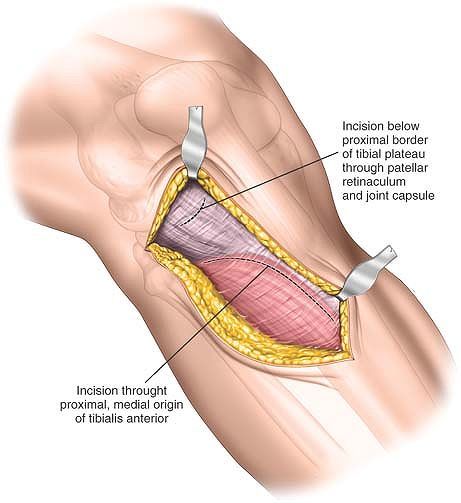

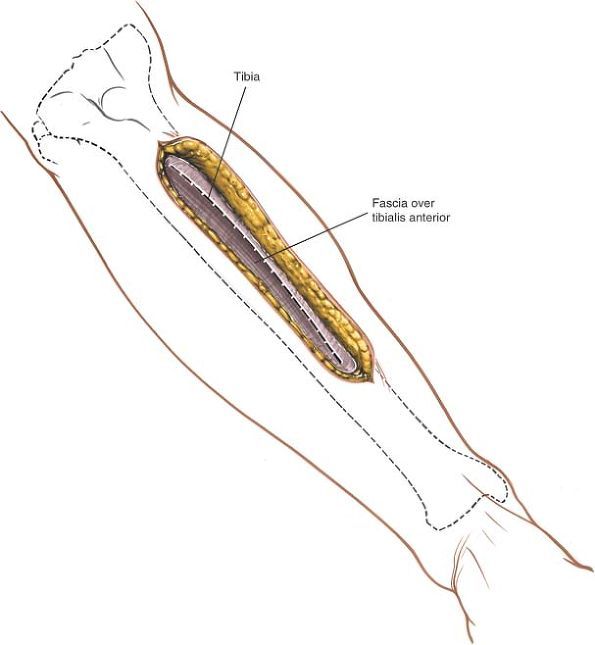

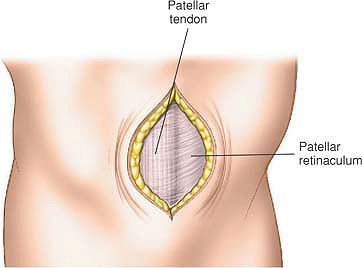

Figure 11-3

Deepen the incision proximally through subcutaneous tissue to expose the lateral aspect of the knee joint capsule. Incise the knee joint capsule longitudinally down to the superior border of the lateral meniscus. Take care not to divide the lateral meniscus inadvertently. Below the joint line, deepen the incision through subcutaneous tissue to expose the fascia overlying the tibialis anterior muscle. |

tissue to expose the lateral aspect of the knee joint capsule. Incise

the knee joint capsule longitudinally down to the superior border of

the lateral meniscus. Take care not to divide the lateral meniscus

inadvertently. Below the joint line, deepen the incision through

subcutaneous tissue and incise the fascia overlying the tibialis

anterior muscle (Fig. 11-3).

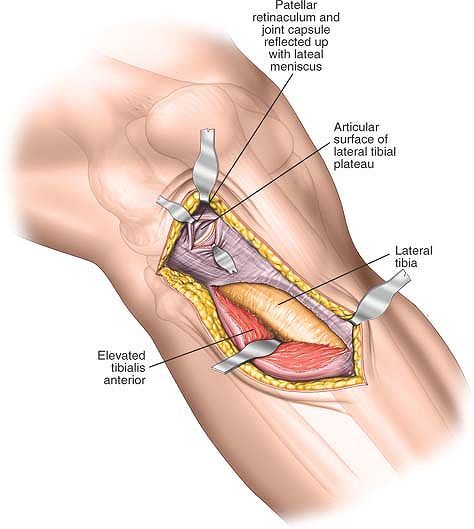

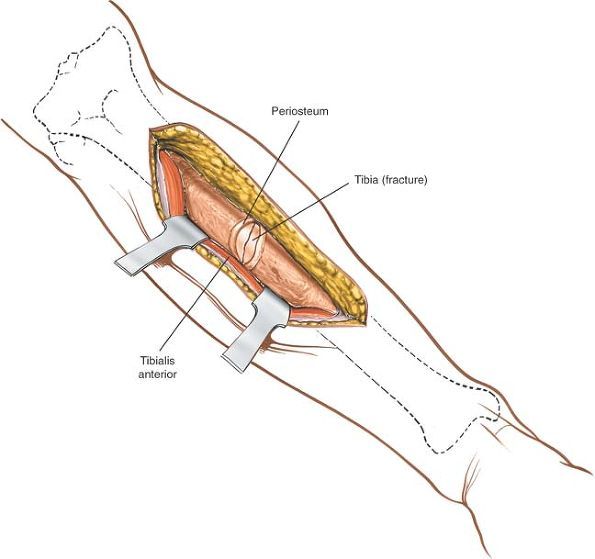

synovium. Carefully detach the lateral meniscus from its soft-tissue

attachments inferiorly and develop a plane between the undersurface of

the lateral meniscus and the underlying tibial plateau. Insert stay

sutures to the periphery of the meniscus to facilitate reattachment

during closure. Ensure that the anterior attachment of the meniscus

remains intact. Detach a sufficient amount of the meniscus to allow

adequate visualization of the superior surface of the lateral tibial

plateau. Using an elevator, inferiorly detach some of the origin of

tibialis anterior from the proximal tibia. Try to work in a plane

between the periosteum and the muscle (Fig. 11-4).

variable course. Normally, it lies well posterior to the area of

dissection and it should not be injured.

soft-tissue attachments inferiorly to allow adequate visualization of

the articular surface of the tibia. Take care not to completely detach

it, preserving anterior and posterior attachments, however. It is at

most risk during the incision of the knee joint synovium.

lateral aspect of the knee between the femur and the tibia allows a

varus distraction force to be applied to the knee joint, thereby

opening up the lateral compartment.

extend the approach proximally, continue the skin incision along the

lateral aspect of the patella, then curve posteriorly over the

lateral

aspect of the distal femur. Deepen the incision through the lateral

joint capsule to gain access to the knee joint and the distal femur

proximally.

|

|

Figure 11-4

Proximally enter the knee joint by dividing the synovium. Carefully detach the lateral meniscus from its soft-tissue attachments inferiorly and develop a plane between the undersurface of the lateral meniscus and the underlying tibial plateau. Distally incise the fascia overlying the tibialis anterior muscle. Mobilize the muscle belly from the lateral aspect of the tibial shaft. |

extend the approach distally, continue the incision in a longitudinal

fashion, remaining 1 cm lateral to the anterior border of the tibia.

Extend it all the way down to the ankle proximally. Deep dissection,

either by splitting the tibialis anterior muscle or by detaching it

from the lateral aspect of the tibia, allows access to the tibial shaft

down to its proximal quarter.

access for open reduction and internal fixation of proximal tibial

fractures. The approach is of most use in treating fractures, which do

not involve the joint surface, or where reduction and fixation of the

intra-articular element of the fracture can be carried out without

formal exposure of the joint surface.

aspect of the proximal tibia and can be applied percutaneously. As with

the anterolateral approach to the proximal tibia, the soft tissues in

this area are critical, and massive swelling or blistering are

contraindications to immediate surgery.

patella tendon. Confirm the position of the joint line by flexing and extending the knee.

|

|

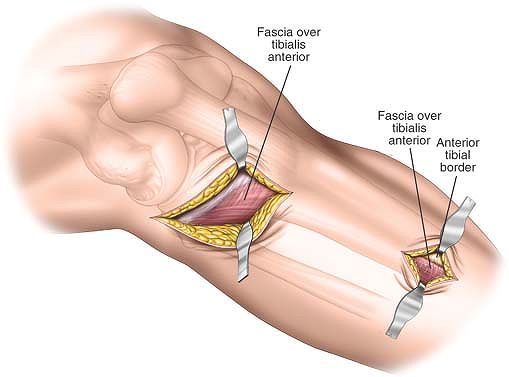

Figure 11-5

Distally make a 5- to 6-cm longitudinal incision approximately 2 cm lateral to the tibial crest and parallel with it. The size and length of the distal window depends on the pathology to be treated and the implants to be used. |

just proximal and lateral to Gerdy’s tubercle and extend it distally in

a curvilinear fashion for approximately 5 cm to 6 cm.

approximately 2 cm lateral to the tibial crest and parallel with it.

The size and length of the distal window depends on the pathology to be

treated and the implants to be used. The position of the incision often

can only be assessed using the image intensifier control (Fig. 11-5).

dissection is epi-periosteal and submuscular and does not disturb the

nerve supply to the extensor compartment (superficial peroneal nerve).

skin incision to access the proximal tibia. Retract the tibialis

anterior muscle laterally and distally, preserving as much soft tissue

as possible.

incision through subcutaneous tissue, then incise the deep fascia in

the line of the skin incision (Fig. 11-6).

to allow adequate visualization of the pathology and placement of

implants. Try to preserve as much soft-tissue attachments to the bone

as possible.

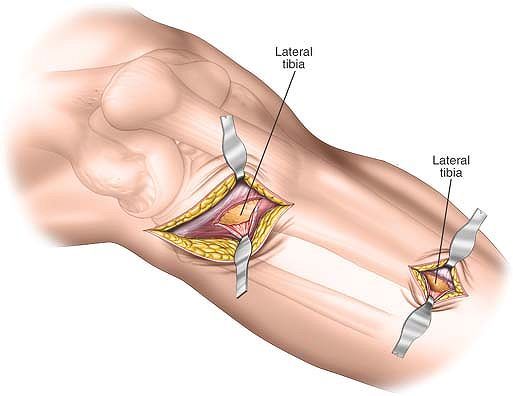

muscle and the lateral border of the tibia. This can easily be achieved

with blunt dissection using the Cobb elevator.

two incisions running along the lateral border of the tibia by using a

blunt elevator (Fig. 11-7).

nerve should be posterior to the proximal dissection. The course of the

nerve is variable, thus care must be taken during the superficial

surgical dissection to ensure that the nerve is not damaged.

of the origin of tibialis anterior from the lateral aspect of the tibia

allows visualization of the lateral aspect of the whole proximal third

of the tibia.

|

|

Figure 11-6

Distally deepen the approach in the line of the skin incision through subcutaneous tissue, then incise the deep fascia in the line of the skin incision to expose the periosteum overlying the lateral aspect of the lateral tibial plateau. Distally incise the

subcutaneous tissues and the fascia covering the tibialis anterior muscle in the line of the skin incision. Finally, split the fibers of the tibialis anterior muscle to reveal the periosteum covering the lateral aspect of the tibial shaft. |

|

|

Figure 11-7

Develop an epi-periosteal plane to connect the two incisions running along the lateral border of the tibia by using a blunt elevator. |

large posteromedial fragment. Accurate reduction of this fragment onto

the tibial shaft is critical to allow reconstruction of the joint.

Plates applied to the posteromedial aspect of the tibia prevent varus

deformity, the most common deformity of the proximal tibia after

fracture. Biomechanically, these plates are on the compression side of

the bone. Another potential advantage of the incision is that the skin

and soft tissues on the posteromedial aspect of the tibia are usually

free from blisters that commonly occur on the anterior portion of the

tibia. However, if the soft tissues on the posteromedial aspect of the

proximal tibia are poor, surgery must be delayed until the soft-tissue

conditions have improved.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the medial tibial plateau

![]() Figure 11-8

Figure 11-8

Place the patient supine on a radiolucent table. Position a sandbag

beneath the contralateral hip to roll the patient approximately 20°. -

Open reduction and internal fixation of complex bicondylar tibial plateau fractures

-

Upper tibial osteotomy

-

Drainage of abscess

-

Biopsy of tumors

ensure that adequate visualization of the fracture can be obtained

using an image intensifier. Position a sandbag beneath the

contralateral hip to roll the patient approximately 20° (Fig. 11-8).

This will increase the external rotation of the affected limb, bringing

the posteromedial corner of the tibia forward. Ease of access is also

improved if the surgeon stands on the opposite side of the table from

the approach. Exsanguinate the limb by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes

or by applying a soft rubber bandage. Inflate a tourniquet.

posteromedial surface where the tibia flares is easily palpated, even

in very obese individuals.

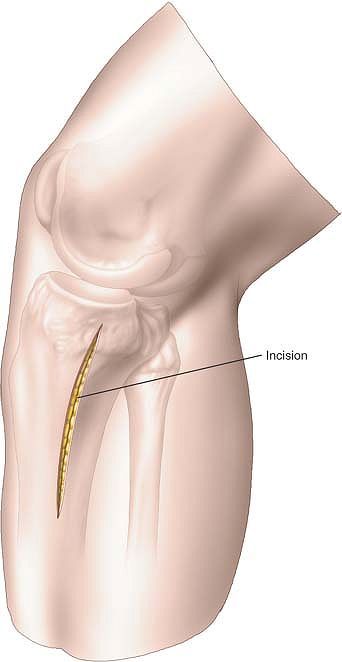

posteromedial border of the proximal tibia. The exact length of the

incision will depend on the pathology to be treated and the implant to

be used (Fig. 11-9).

|

|

Figure 11-9

Make a 6-cm longitudinal incision overlying the posteromedial border of the proximal tibia. The exact length of the incision will depend on the pathology to be treated and the implant to be used. |

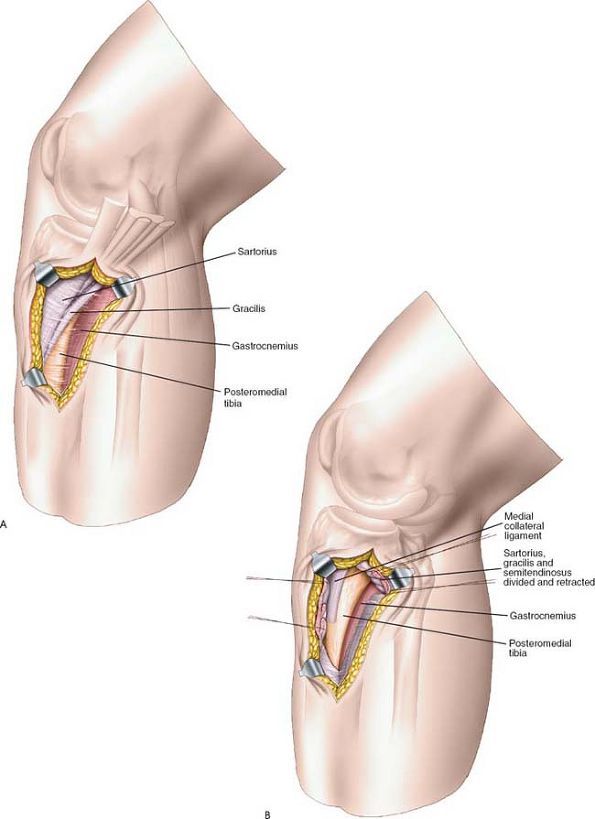

long saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve will be just anterior to

your surgical approach; these structures should be identified and

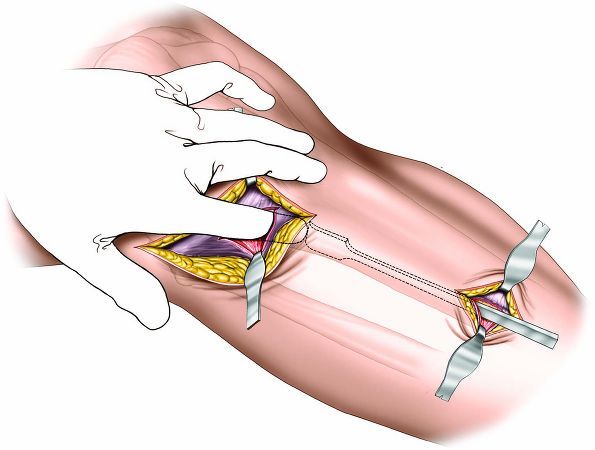

preserved. Identify the pes anserinus expansion overlying the tibia (Fig. 11-10A).

longitudinally in the line of the skin incision or identify the

anterior border of the pes and partially resect it from its insertion

into the tibia, reflecting it posteriorly (Fig. 11-10B).

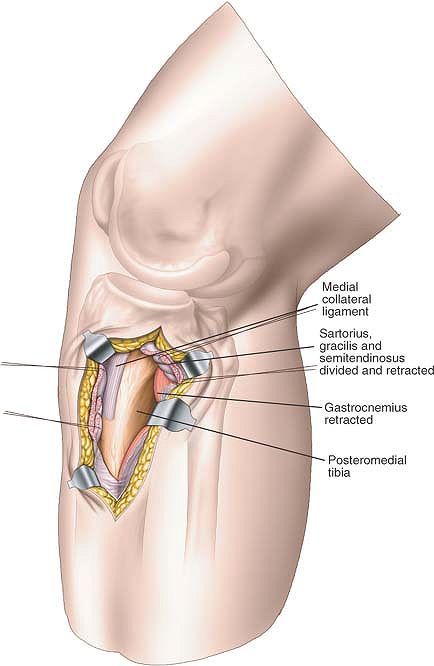

anserinus and the medial head of the gastrocnemius at the posteromedial

border of the tibia. The muscle can be gently freed from the bone by

blunt dissection (Fig. 11-11).

incision may be extended proximally around the medial border of the

tibia. Access to the popliteal artery and vein for vascular surgery is

also possible through this extension.

medial side of the posteromedial tibia. Not only will this give you

access to the posteromedial border of the tibia, but it also provides

access to both the superficial and deep posterior compartments of the

leg for compartment release.

|

|

Figure 11-10 (A)

Deepen the incision through the subcutaneous fat. The long saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve will be just anterior to the surgical approach; these structures should be identified and preserved. Identify the pes anserinus expansion overlying the tibia. (B) To approach the tibia, either divide the pes anserinus longitudinally in the line of the skin incision or identify the anterior border of the pes and partially resect it from its insertion into the tibia, reflecting it posteriorly. |

|

|

Figure 11-11

Develop an epi-periosteal plane between the pes anserinus and the medial head of the gastrocnemius at the posteromedial border of the tibia. The muscle can be gently freed from the bone by blunt dissection. |

medial (subcutaneous) and lateral (extensor) surfaces of the tibia. It

is used for the following:

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of tibial fractures1

-

Bone grafting for delayed union or nonunion of fractures2

-

Implantation of electrical stimulators3

-

Excision of sequestra or saucerization in patients with osteomyelitis

-

Excision and biopsy of tumors

-

Osteotomy

are placed correctly biomechanically on the medial (tensile) side of

the bone; they also are easier to contour there. Some surgeons prefer

to use the lateral surface for plating, however, to avoid the problems

of subcutaneous placement.

used if this approach is to be used in conjunction with the exploration

of an open wound. If you wish to use a tourniquet, exsanguinate the

limb by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes, then inflate a tourniquet (Fig. 11-12).

|

|

Figure 11-12 Position for the anterior approach to the tibia.

|

roughly triangular when viewed in cross section. It has three borders,

one anterior, one medial, and one interosseous (posterolateral). These

borders define three distinct surfaces: (1) a medial subcutaneous

surface between the anterior and medial borders, (2) a lateral

(extensor) surface between the anterior and interosseous borders, and

(3) a posterior (flexor) surface between the medial and interosseous

(posterolateral) borders. The anterior and medial borders and the

subcutaneous surface are easily palpable.

the leg parallel to the anterior border of the tibia and about 1 cm

lateral to it. The length of the incision depends on the requirements

of the procedure because of the poor vascularity of the skin. It is

safer to make a longer incision than to retract skin edges forcibly to

obtain access. The tibia can be exposed along its entire length (Fig. 11-13).

dissection is epi-periosteal and does not disturb the nerve supply to

the extensor compartment.

surface of the tibia. The long saphenous vein is on the medial side of

the calf and must be protected when the medial skin flap is reflected (Fig. 11-14).

blood supply to the bone in fractures that interfere with its main

blood supply. For this reason, periosteal stripping must be kept to an

absolute minimum. In particular, never strip the periosteum off an

isolated fragment of bone, or the bone will become totally avascular.

|

|

Figure 11-13 Make a longitudinal incision on the anterior surface of the leg.

|

and retract it laterally to expose the lateral surface of the bone. The

tibialis anterior is the only muscle to take origin from the lateral

surface of the tibia; detaching the muscle completely exposes that

surface (see Figs. 11-15 and 11-31).

which runs up the medial side of the calf, is vulnerable during

superficial surgical dissection and should be preserved for future

vascular procedures, if at all possible (see Fig. 11-31).

avoid infection of the tibia. Although longitudinal incisions over the

tibia heal well, transverse incisions and irregular wounds may heal

poorly, especially in elderly individuals. The skin over the lower

third of the tibia is very thin; wounds in that area heal badly,

especially in patients with chronic venous insufficiency.

that is stripped from bone in this approach when it is used for

fracture work. Devascularized bone, no matter how well it is reduced

and fixed, will not unite. Using care and appropriate reduction

forceps, it usually is possible to preserve soft-tissue attachments of

all but the smallest fragments of bone.

the skin incision; the whole subcutaneous surface of the tibia may be

exposed, if necessary.

anterior approach, continue the epi-periosteal dissection posteriorly

around the medial border. Proximally, lift the flexor digitorum longus

muscle off the posterior surface of the tibia subperiosteally.

Distally, lift off the tibialis posterior muscle. This procedure

exposes the posterior surface of the bone, but does not offer as full

an exposure as does the posterolateral approach. It probably is useful

only for the insertion of bone graft as part of an internal fixation

carried out through this anterior route.

|

|

Figure 11-14

Elevate the skin flaps over the medial portion of the tibialis anterior and the subcutaneous medial surface of the tibia. To expose the lateral surface of the tibia, incise the deep fascia over the medial border of the tibialis anterior. |

extend the approach proximally, continue the skin incision along the

medial side of the patella. Deepen the incision through the medial

patellar retinaculum to gain access to the knee joint and the patella.

(For details, see Medial Parapatellar Approach in Chapter 10, Fig. 10-10.)

Alternatively, extend the wound proximally along the lateral side of

the patella. Deepen that wound through the lateral patellar retinaculum

to gain access to the lateral compartment of the knee.

extend the approach distally, curve the incision over the medial side

of the hind part of the foot. Deepening the wound provides access to

all the structures that pass behind the medial malleolus. Continue the

incision onto the middle and front parts of the foot. (For details, see

Anterior and Posterior Approaches to the Medial Malleolus in Chapter 12, Fig. 12-6.)

|

|

Figure 11-15 Elevate the tibialis anterior from the lateral surface of the tibia. Incise the periosteum; elevate it only as necessary.

|

surface, access to the bone is easy through the skin incisions lying

directly over the bone. The soft tissues overlying the distal tibia are

thin and fragile, consisting only of skin and underlying fascia.

Problems such as swelling, blistering, and profuse edema are common in

fractures in this area. The minimal access approach to the distal tibia

should only be used when the soft tissues are in good condition, and a

delay in carrying out definitive surgery in fractures in this area is

not uncommon.

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of

fractures of the distal tibia, especially multifragmentary fractures of

the distal tibial metaphysis -

Biopsy of tumor

-

Corrective osteotomies

-

Malunion

Ensure that adequate X-rays can be taken before prepping and draping

the patient. Place a small sandbag beneath the ipsilateral buttock to

correct the natural external rotation of the limb. Ensure that the

patella is facing anteriorly. This will make it easier for you to

assess the quality of the reduction regarding rotation. Exsanguinate

the limb either by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes or by applying a

soft rubber bandage. Inflate a tourniquet.

|

|

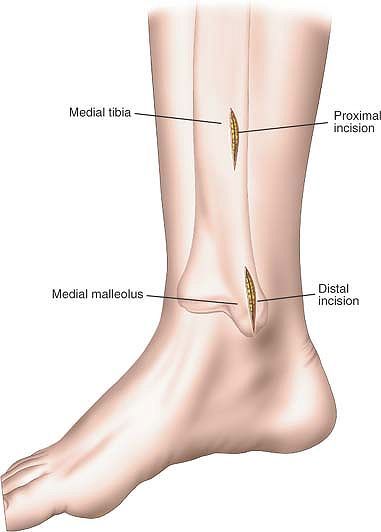

Figure 11-16

Distally make a 3- to 4-cm incision starting just distal to the medial malleolus and extend the incision proximally overlying the subcutaneous surface of the tibia, halfway between the anterior and posterior border. Proximally make a longitudinal incision overlying the subcutaneous surface of the tibia, halfway between the anterior and posterior borders. |

distal to the medial malleolus, extending the incision proximally

overlying the subcutaneous surface of the tibia, halfway between the

anterior and posterior border.

subcutaneous surface of the tibia, halfway between the anterior and

posterior borders (Fig. 11-16). The positioning

and size of proximal incision relates to the implants used and can only

be confirmed under image intensifier control.

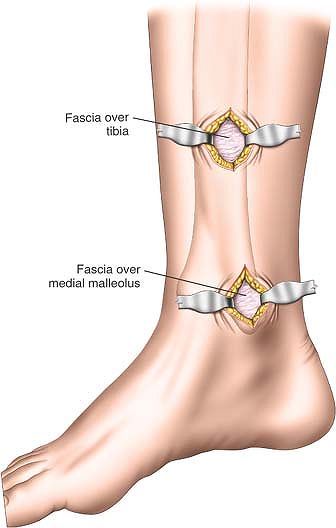

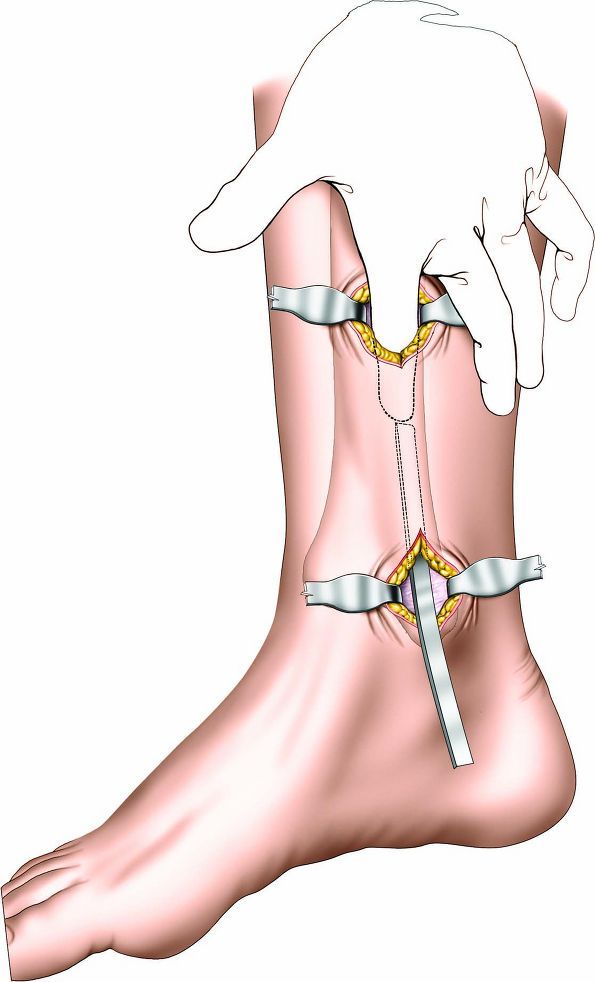

overlying the tibia. Because the periosteum of the tibia is a very

precious structure that supplies significant amounts of blood to the

bone, it should not be removed (Fig. 11-17).

proximal skin incisions using a blunt dissector, such as a Cobb

elevator (Fig. 11-18).

for the vascular supply of the bone. The plane that lies between the

periosteum and the subcutaneous tissues is used in this approach (not

subperiosteal).

thereby exposing the periosteum covering the subcutaneous surface of

the distal tibia. If such an enlargement is carried out, take care to

preserve as much soft-tissue connection between the skin and

subcutaneous tissue and the underlying structures, to reduce the risk

of skin necrosis.

|

|

Figure 11-17

Proximally and distally deepen the skin incision through subcutaneous tissues to reveal the periosteum covering the subcutaneous surface of the tibia. Try to preserve as much periosteum as possible. |

|

|

Figure 11-18 Develop an epi-periosteal plane between the distal and proximal skin incisions using a blunt dissector such as a Cobb elevator.

|

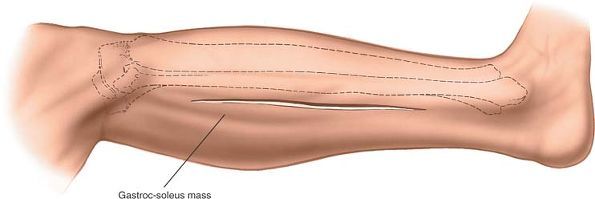

is used to expose the middle two thirds of the tibia when the skin over

the subcutaneous surface is badly scarred or infected. It is a

technically demanding operation. The approach is suitable for the

following uses:

-

Internal fixation of fractures

-

Treatment of delayed union or nonunion5 of fractures, including bone grafting

leg uppermost. Protect the bony prominences of the bottom leg to avoid

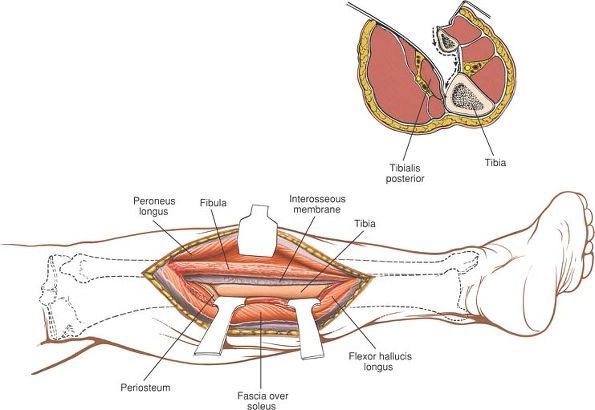

the development of pressure sores. Exsanguinate the limb by elevating

it for 5 minutes, then apply a tourniquet (Fig. 11-19).

|

|

Figure 11-20 Incision of the lateral border of the gastrocnemius.

|

short saphenous vein, which runs up the posterolateral aspect of the

leg from behind the lateral malleolus. Incise the fascia in line with

the incision and find the plane between the lateral head of the

gastrocnemius and soleus muscles posteriorly, and the peroneus

brevis

and longus muscles anteriorly. Muscular branches of the peroneal artery

lie with the peroneus brevis in the proximal part of the incision and

may have to be ligated (Fig. 11-22).

|

|

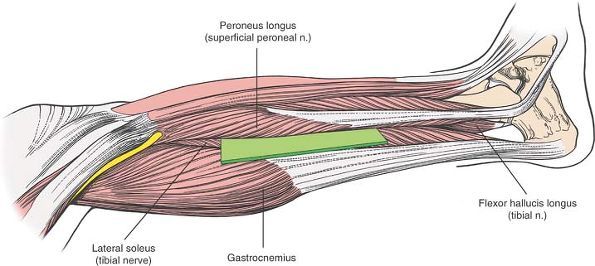

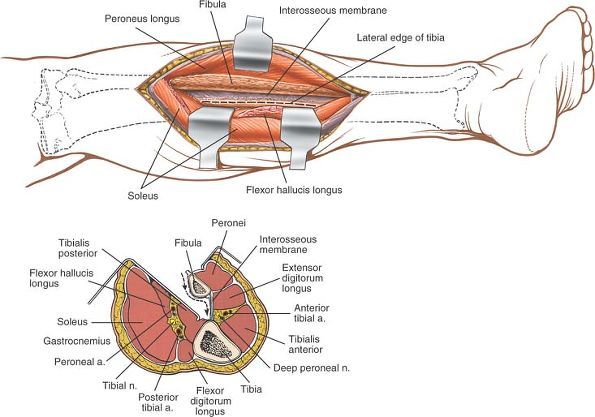

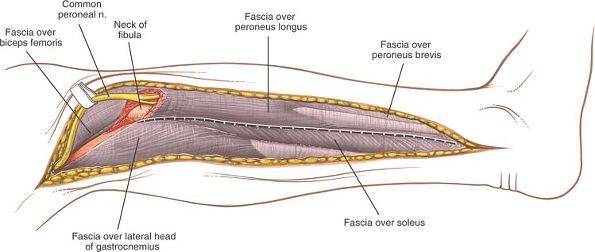

Figure 11-21 The internervous plane lies between the gastrocnemius, soleus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles (which are supplied by the tibial nerve) and the peroneal muscles (which are supplied by the superficial peroneal nerve).

|

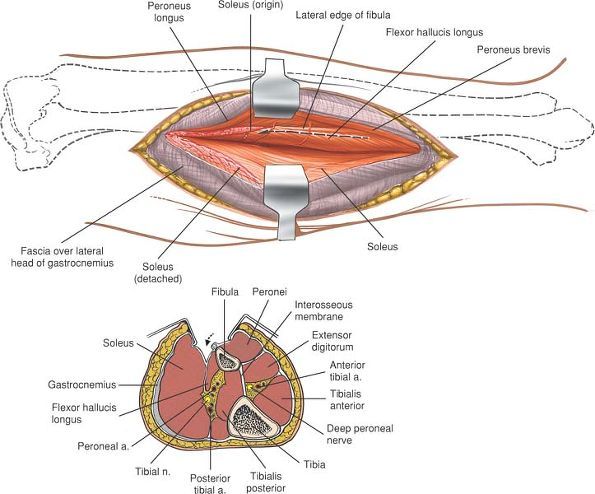

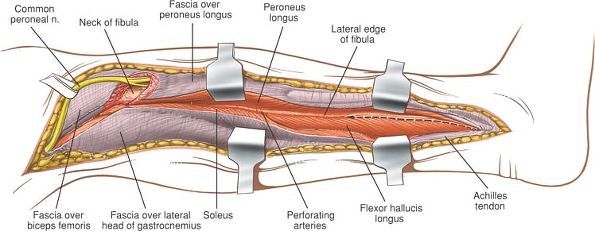

with the gastrocnemius medially and posteriorly; underneath, arising

from the posterior surface of the fibula, is the flexor hallucis longus

(Fig. 11-23).

|

|

Figure 11-22

Reflect the skin flaps. Incise the fascia in line with the incision. Find the plane between the lateral head of the gastrocnemius and soleus posteriorly, and the peroneus brevis and longus anteriorly. |

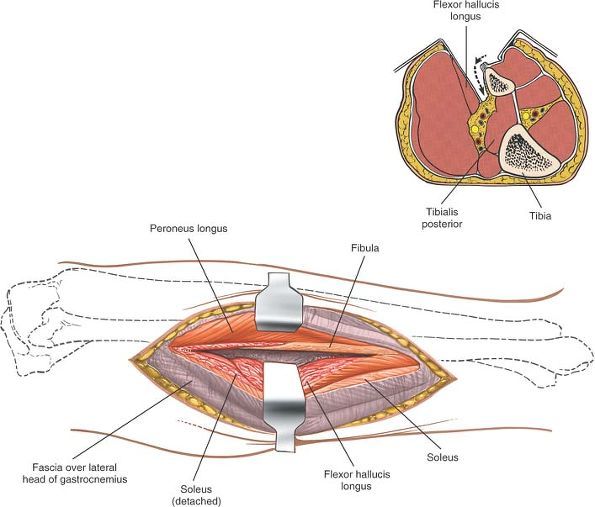

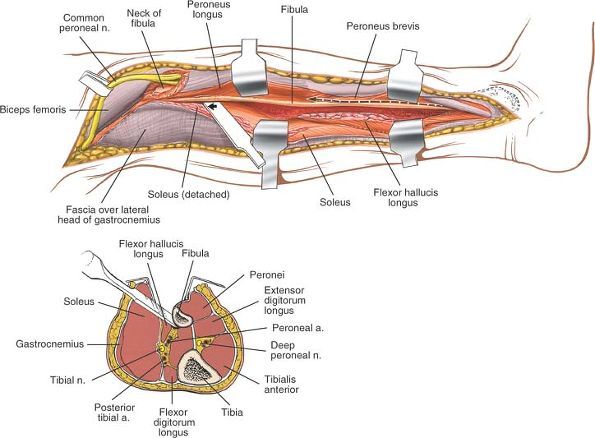

from the fibula and retract it posteriorly and medially. Detach the

flexor hallucis longus muscle from its origin on the fibula and retract

it posteriorly and medially (Fig. 11-24; see Fig. 11-23). Continue dissecting medially across the interosseous membrane, detaching those fibers of the tibialis posterior muscle

that arise from it. The posterior tibial artery and tibial nerve are

posterior to the dissection, separated from it by the bulk of the

tibialis posterior and flexor hallucis longus muscles (Fig. 11-25).

Follow the interosseous membrane to the lateral border of the tibia,

detaching the muscles that arise from its posterior surface

subperiosteally, and expose its posterior surface (Fig. 11-26).

|

|

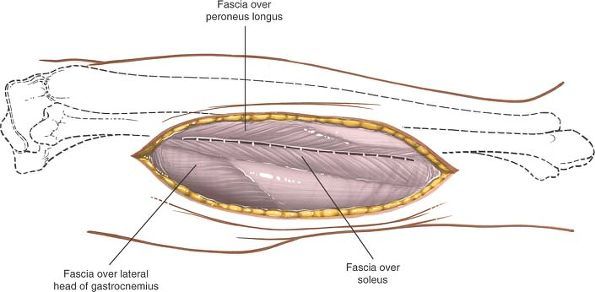

Figure 11-23

Detach the origin of the soleus from the fibula, and retract it posteriorly and medially along with the gastrocnemius. Retract the peroneal muscles anteriorly. Detach the flexor hallucis longus from its origin on the fibula. Develop the plane between the gastrocnemius-soleus group posteriorly and the peroneal muscles anteriorly (cross section). Note the flexor hallucis longus on the posterior surface of the fibula. |

may be damaged when the skin flaps are mobilized. Although the vein

should be preserved if possible, it may be ligated, if necessary,

without impairing venous return from the leg.

cross the intermuscular plane between the gastrocnemius and peroneus

brevis muscles. They should be ligated or coagulated to reduce

postoperative bleeding.

and tibial nerve are safe as long as the surgical plane of operation

remains on the interosseous membrane and does not wander into a plane

posterior to the flexor hallucis longus and tibialis posterior muscles.

|

|

Figure 11-24

Detach the flexor hallucis longus from its origin on the fibula and retract it posteriorly and medially. Continue dissecting posteriorly, staying on the posterior surface of the fibula. Detach the flexor hallucis longus from its origin on the fibula, staying close to the bone (cross section). Retract the muscle medially. |

muscle and the more superficial posterior tibial artery and tibial

nerve, making safe dissection impossible.

approach can be made continuous with the posterior approach to the

ankle if the skin incision is extended distally between the posterior

aspect of the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon.

|

|

Figure 11-25

Continue dissecting medially across the interosseous membrane, detaching those fibers of the tibialis posterior that arise from it. Continue dissecting across the membrane until the posterior aspect of the tibia can be seen. Incise the periosteum on the lateral border of the tibia. Continue the dissection posteriorly across the fibula and the interosseous membrane until the lateral border of the tibia is reached (cross section). Note that the neurovascular structures are protected by the bulk of the tibialis posterior. |

|

|

Figure 11-26

Detach the muscles that arise from the posterior surface of the tibia subperiosteally. Expose the posterior border of the tibia subperiosteally (cross section). The detached tibialis posterior muscle protects the neurovascular structures. |

-

Partial resection of the fibula during tibial osteotomy7 or as part of the treatment of tibial nonunion8,9

-

Resection of the fibula for decompression of all four compartments of the leg10

-

Resection of tumors

-

Resection for osteomyelitis

-

Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the fibula

-

Removal of bone graft–corticocancellous strut grafts. Vascularized fibula grafts are dissected out with their vascular pedicles.

table with the affected side uppermost. Pad the bony prominences of the

other leg to prevent the development of pressure sores. Exsanguinate

the limb by elevating it for 3 to 5 minutes, then apply a tourniquet

(see Fig. 11-19). Alternatively, if this

approach is used in conjunction with a surgical approach to the tibia,

place the patient supine on the operating table. A sandbag placed

underneath the affected buttock will rotate the leg internally. Tilting

the table away from

the

operative side will further increase internal rotation and allow

adequate exposure of the lateral aspect of the leg. Subsequently, if

the sandbag is removed and the table is leveled, the leg will naturally

rotate externally, providing access to the tibia.

|

|

Figure 11-27 Make a long linear incision just posterior to the fibula.

|

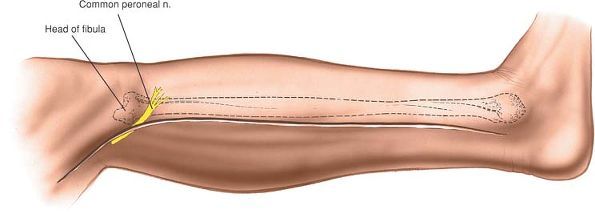

beginning behind the lateral malleolus and extending to the level of

the fibular head. Continue the incision up and back, a handbreadth

above the head of the fibula and in line with the biceps femoris

tendon. Watch out for the common peroneal nerve, which runs

subcutaneously over the neck of the fibula and can be cut if the skin

incision is too bold. The length of the incision depends on the amount

of exposure needed (Fig. 11-27).

incising the deep fascia in line with the incision, taking great care

not to cut the underlying common peroneal nerve. Find the posterior

border of the biceps femoris tendon as it sweeps down past the knee

before inserting into the head of the fibula. Identify and isolate the

common peroneal nerve in its course behind the biceps tendon; trace it

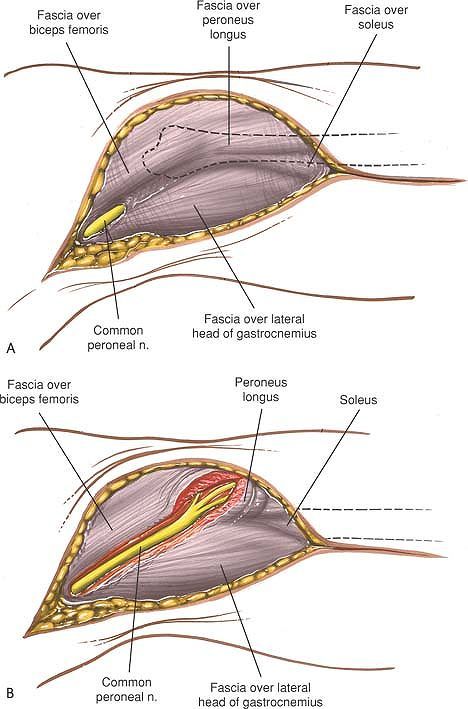

as it winds around the fibular neck (Fig. 11-28).

Mobilize the nerve from the groove on the back of the neck by cutting

the fibers of the peroneus longus that cover the nerve and gently

pulling the nerve forward over the fibular head with a strip of

corrugated rubber drain. Identify and preserve all branches of the

nerve (Fig. 11-29).

with the common peroneal nerve retracted anteriorly, incise the

periosteum of the fibula longitudinally in the line with this plane of

cleavage. Continue the incision down to bone (Fig. 11-30).

muscles that originate from the fibula have fibers that run distally

toward the foot and ankle. Therefore, to strip them off cleanly, you

must elevate them from distal to proximal. Most muscles originate from

periosteum or fascia; they can be stripped. Muscles attached directly

to bone are difficult to strip; they usually must be cut (Fig. 11-31, and cross-section).

|

|

Figure 11-28 (A) Expose the common peroneal nerve in the proximal end of the incision along the posterior border of the biceps. (B)

Continue exposing the common peroneal nerve distally as it winds around the neck of the fibula in the substance of the peroneus longus. |

|

|

Figure 11-29 Retract the peroneal nerve anteriorly, and incise the fascia between the peroneal muscles and the soleus muscle.

|

|

|

Figure 11-30

Develop the intermuscular plane between the peroneal muscles and the soleus muscle down the lateral edge of the fibula. Strip the flexor muscles from the posterior aspect of the fibula in a distal to proximal direction. |

|

|

Figure 11-31

Strip the flexor hallucis longus and the soleus from the posterior aspect of the fibula, and strip the peroneal muscles from the anterior surface of the fibula in a distal to proximal direction. Strip the flexor muscles from the posterior aspect of the fibula (cross section). Avoid neurovascular structures by staying close to the bone. |

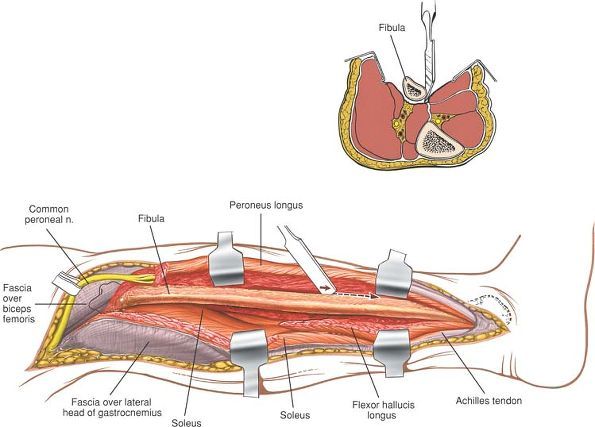

interosseous membrane, has fibers that run obliquely upward. To

complete the dissection, strip the interosseous membrane

subperiosteally from proximal to distal (Fig. 11-32, and cross-section).

vulnerable as it winds around the neck of the fibula. The key to

preserving the nerve is to identify it proximally as it lies on the

posterior border of the biceps femoris. It then can be safely traced

through the peroneal muscle mass. If possible, avoid retracting the

nerve. The dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve is

susceptible to injury at the junction of the distal and middle thirds

of the fibula; if it is damaged, it causes numbness on the dorsum of

the foot.

the skin incision distally by curving it over the lateral side of the

tarsus. To gain access to the sinus tarsi and the talocalcaneal,

talonavicular, and calcaneocuboid joints, reflect the underlying

extensor digitorum brevis muscle. This extension is used frequently for

lateral operations on the leg and foot (see Lateral Approach to the Hindpart of the Foot in Chapter 12).

|

|

Figure 11-32

Retract the peroneal muscles anteriorly. Strip the interosseous membrane from the anterior border of the fibula in a proximal to distal direction. Strip the muscles from the anterior surface of the fibula, and strip the interosseous membrane from its fibular attachment in a proximal to distal direction (cross section). |

has a large subcutaneous surface that allows access to the bone along

its entire length; the fibula is enclosed almost completely in muscle.

Only at its proximal end and in the lower third of the bone does the

fibula develop a subcutaneous surface, which terminates in the lateral

malleolus. For this reason, operations on most of the fibula almost

always involve extensive stripping of muscle off bone. In addition, the

tibia has no major neurovascular structures running directly on it

other than its nutrient artery; the fibula has close ties to the common

peroneal nerve and its branches.

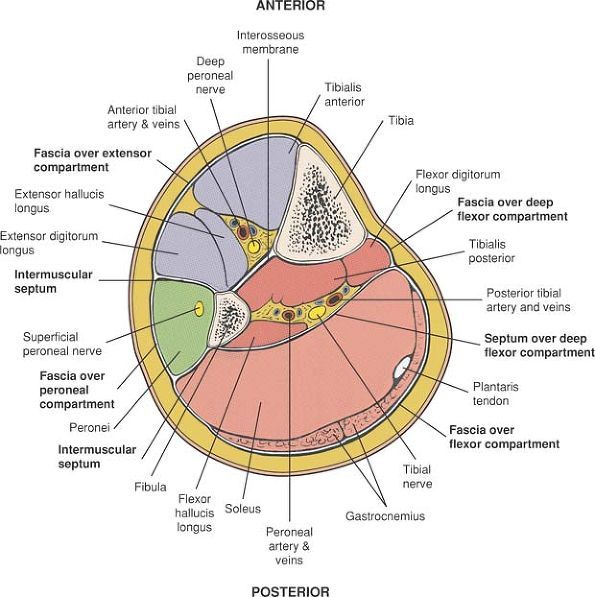

unyielding structure that encloses the calf muscles. Where the bones

become subcutaneous, the fascia usually is attached to the border of

the bone.

pass from the deep surface of the encircling fascia to the fibula and

enclose the peroneal or lateral compartment of the leg.

of the foot and ankle. Its medial boundary is the lateral (extensor)

surface of the tibia, and its lateral boundary is the extensor surface

of the fibula and anterior intermuscular septum. The anterior

compartment

is

enclosed by the deep fascia of the leg and all its muscles are supplied

by the deep peroneal nerve. The compartment’s artery is the anterior

tibial artery (Fig. 11-34).

|

|

Figure 11-33 The fibro-osseous compartments of the leg.

|

intermuscular septum in front, by the posterior intermuscular septum

behind, and by the fibula medially. It contains the peroneal muscles,

which evert the foot. The superficial peroneal nerve supplies all the

muscles in the compartment. No artery runs in it; its muscles receive

their supply from several branches of the peroneal artery (Fig. 11-35).

muscles: the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris. The compartment is

separated from the lateral (peroneal compartment) by the posterior

intermuscular septum. It is separated from the deep posterior flexor

compartment by a fascial layer.

muscles: the tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, and flexor

digitorum longus. It also contains the tibial nerve and posterior

tibial artery. It is separated from the superficial flexor compartment

by the posterior intermuscular septum and from the anterior compartment

by the interosseous membrane.

|

|

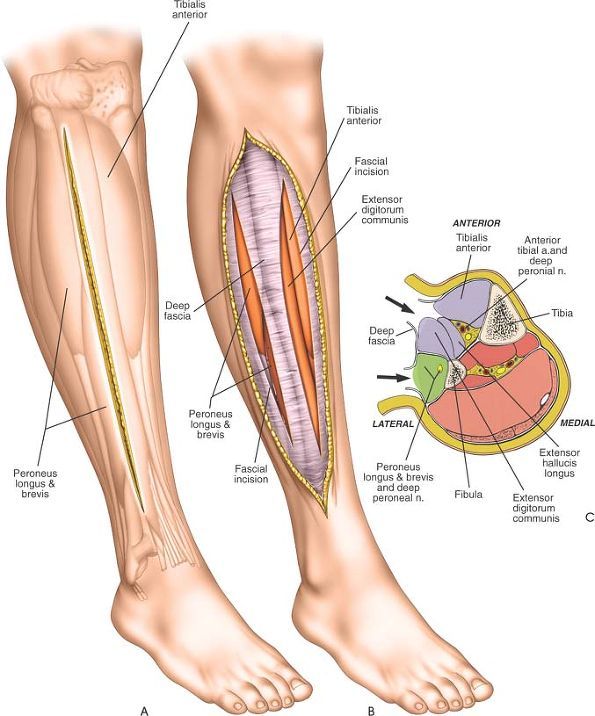

Figure 11-34

To decompress the anterior and lateral compartments, make a longitudinal incision overlying the anterolateral aspect of the lower leg. (A) Begin at the level of the tibial tubercle and extend the incision to end 6 cm above the level of the ankle. (B) Incise the fascia overlying the anterior and lateral compartments in the line of the skin incision. (C) Transverse section showing the fascial compartments. Incising the fascia overlying the anterior, lateral, and superficial flexor compartments is easy. Decompressing the deep flexor compartment may involve lifting the soleus muscle of the intermuscular septum and dividing that septum under direct vision, taking care to avoid the posterior neurovascular bundle. |

|

|

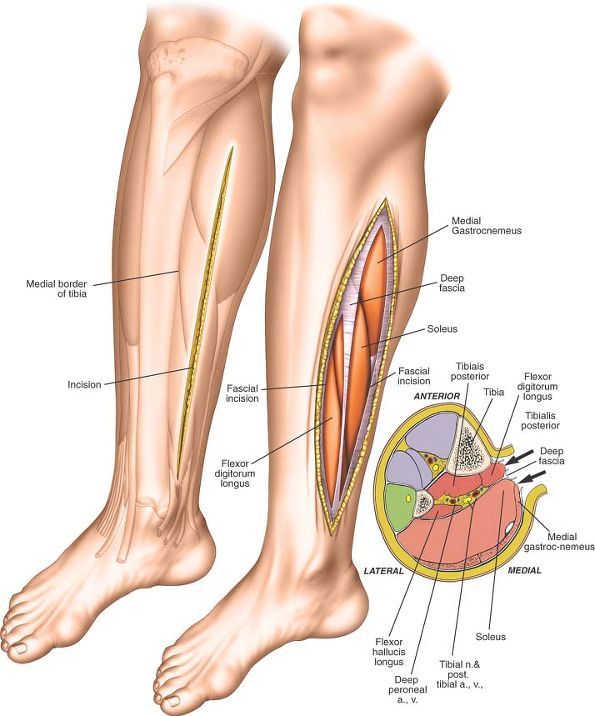

Figure 11-35

To decompress the superficial and deep flexor compartments, make a longitudinal incision overlying the posteromedial aspect of the lower leg. Begin at the level of the tibial tubercle and extend the incision distally, ending 6 cm above the ankle. At right, transverse section showing the fascial compartments. Incising the fascia overlying the anterior, lateral, and superficial flexor compartments is easy. Decompressing the deep flexor compartment may involve lifting the soleus muscle of the intermuscular septum and dividing that septum under direct vision, taking care to avoid the posterior neurovascular bundle. |

for the insertion of intramedullary nails used in the treatment of the

following:

-

Fresh tibial shaft fractures

-

Pathological tibial shaft fractures

-

Delayed union and nonunion of tibial shaft fractures

seen in femoral nails. All tibial nails are angled at their upper end

to allow insertion via an anterior route, and all tibial nails are

straight when viewed in the anterior-posterior plane.

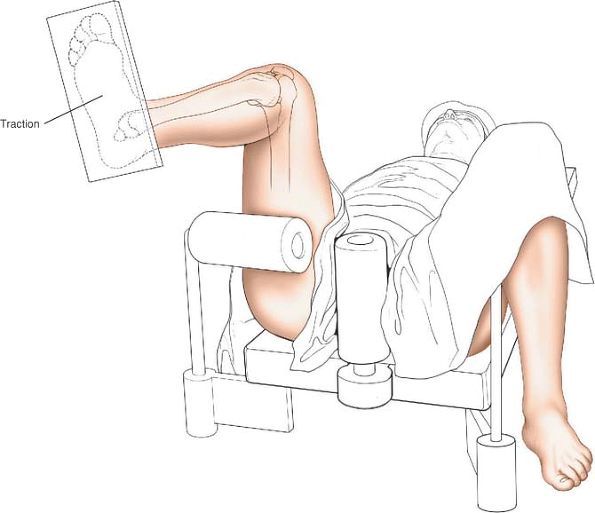

nails. Placing the patient on a traction table allows greater control

of the fracture and easier distal locking. The free leg position allows

greater knee flexion, which makes nail insertion easier.

|

|

Figure 11-36

Traction table position. Flex the hip 60°. Flex the knee to 100° to 120° of flexion, and apply traction by strapping the foot to the sole of a traction boot. Place the opposite leg in a support with the hip flexed and abducted and the knee flexed. |

patient supine on an operating table. Flex the hip to 60°. Place a

support behind the posterior aspect of the distal thigh. Take care not

to place the support in the popliteal fossa, where it will create

pressure on the popliteal vein (Fig. 11-36; see Fig. 10-59).

traction by strapping the patient’s foot to the sole of a traction boot

or a Steinmann pin inserted through the os calcis. A conventional

traction boot extends 5 to 8 cm

above

the heel. Use of this boot will prevent the insertion of distal locking

bolts because the required skin incision will be covered by the boot.

Again, ensure that the thigh support does not compress the structures

within the popliteal fossa. To reduce the risk of thermal necrosis

during the reaming of the medullary canal, do not use a tourniquet.

Note that minimal traction is required to reduce a fresh tibial shaft

fracture.

|

|

Figure 11-37

Free leg position. Place the patient supine on the operating table. Remove the end of the table. Allow the injured knee to flex over the end of the table. Place the contralateral leg in a support with the hip flexed and abducted and the knee flexed. |

the end of the table, and allow the injured knee to flex over the end

of the table. Place the contralateral leg in a support with the hip

flexed and abducted and the knee flexed. Do not use a tourniquet (Fig. 11-37).

|

|

Figure 11-38 Make a 5-cm long incision overlying the medial edge of the patella tendon.

|

tibia, beginning at the inferior border of the patella and extending

the incision down to just above the tibial tubercle (Fig. 11-38). This incision should overlie the medial border of the patellar tendon.

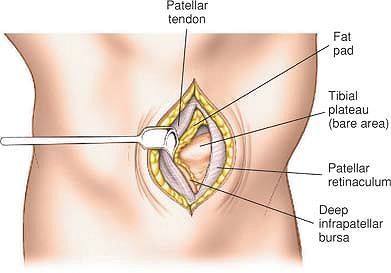

from the medial aspect of the patellar tendon in the line of the skin

incision. Numerous small arterial vessels are usually encountered and

will need to be coagulated. Identify the medial border of the patellar

tendon, and incise this fascia longitudinally along the border (Fig. 11-39).

|

|

Figure 11-39 Deepen the skin incision to expose the medial edge of the patella tendon.

|

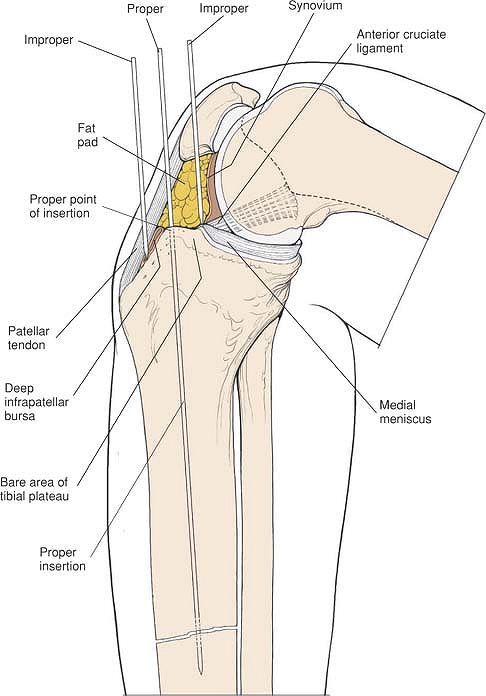

expose a small bursa between the tendon and the anterior aspect of the

tibia—the deep infrapatellar bursa (Fig. 11-40).

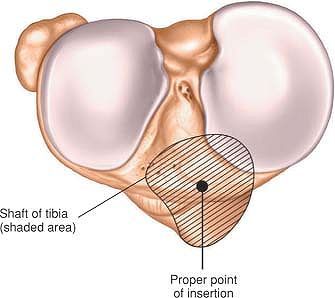

The precise entry point of the nail into the medullary canal of the

tibial shaft can be calculated preoperatively by overlaying a template

of the nail on the anterior-posterior radiograph of the injured tibia.

The entry point of the nail lies at the very proximal end of the tibia

at the junction of the anterior and superior aspects of the bone. Note

that this entry point, although on the superior aspect of the tibia, is

extrasynovial (Fig. 11-42). The entry point for

the nail must be confirmed radiographically (in the operating room) in

both the anterior-posterior and lateral planes before entry is made (Fig. 11-41).

should be warned that an area of numbness is likely following this surgical approach (see Fig. 10-37).

|

|

Figure 11-40 Incise the fascia on the medial edge of the patella tendon and retract the tendon laterally.

|

will be created at the fracture site in proximal fractures. If the

entry point is too far lateral, a varus deformity will be created at

the fracture site in proximal fractures.

|

|

Figure 11-41

View of the superior surface of the tibia, showing the entry point of the nail. The insertion point is extrasynovial, lying anterior to the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament and lateral to the anterior horn of the medial meniscus. |

flexed to beyond 90° due to pressure of the nail on the anterior aspect

of the patella. Such pressure may be

sufficient to produce a compression lesion of the patellofemoral joint

or even transient subluxation of the patella, producing damage to the

articular cartilage of the patella. For that reason, many surgeons

prefer a free leg position, which allows greater degrees of flexion

than can be easily obtained using a traction table.

point of the nail but has no other uses. It cannot be usefully enlarged.

|

|

Figure 11-42

Correct and incorrect insertion points. Note that if the entry point is too far posterior then damage to the insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament on the tibia will occur. An entry point that is too far anterior will cause splintering of the anterior cortex of the tibia on nail insertion. |

DB: Treatment of ununited fractures by onlay bone grafts without screw

or tie fixation and without breaking down of the fibrous union. J Bone

Joint Surg 29:946, 1947

D, Lewis GN, Cass CA: Clinical experience in Australia with an

implanted bone growth stimulator (1976–1978). Orthop Transcripts 3:288,

1979

PH: A simplified surgical approach to the posterior tibia for bone

grafting and fibular transference. J Bone Joint Surg 27:496, 1945

KG, Barnett HC: Cancellous-bone grafting for nonunion of the tibia

through the postero-lateral approach. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 37:1250,

1955

MB: Osteotomy about the knee for degenerative and rheumatoid arthritis:

indications, operative technique and results. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]

55:234, 1973

A, Albrecht S: Palsy of the deep peroneal nerve after proximal tibial

osteotomy: an anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 74:1180, 1992

PL, Neiman R, Finkemeier CF et al: Incision placement for

intramedullary tibial nailing: an anatomic study. J Orthop Trauma

16:687, 2002

M, Audige L, Ellis T et al: Operative treatment of extra-articular

proximal tibial fractures. J Orthop Trauma 17:591, 2003

J, Prickett W, Song E et al: Extraosseous blood supply of the tibial

and the effects of different plating techniques. A human cataveric

study. J Orthop Trauma 16:691, 2002

PA, Ziowodzki M, Kregor PJ: Less invasive stabilization system (LISS)

for fractures of the proximal tibia: indications, surgical technique

and preliminary results for the UMC clinical trial. Injury 34

(suppl):A16, 2003

K, Singh P, Elliott DS: Percutaneous plating of low energy unstable

tibial plateau fractures. A new technique. Injury 32:229, 2001

JF, Jajducka CL, Harper J: Minimal internal fixation and calcium

phosphate cement in the treatment of fractures of the tibial plateau. A

pilot study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 85:68, 2003