The Pediatric Orthopaedic Examination

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hensinger spoke of the

responsibilities of orthopaedists to society. He noted that Hippocrates

provided the initial ethical principle for us to be honest, truthful,

and to have a scientific approach to patient care: to “do no harm.”

Hensinger challenged us to aspire to the highest level of knowledge,

education, and research: to “do good.” Caring for children provides an

opportunity to have an impact not only on their lives but also on the

members of their immediate family and society at large.

examination. The pediatric orthopaedic examination is a tool in

evidence-based medicine. If your examination is associated with human

research, then appropriate protection of privacy and informed consent

are needed. The recording of information and measurements will both

contribute to the care and satisfaction of individual children and

their families, as well as provide a record for review. As such, your

examination is part of a medicolegal document. This chapter provides

suggestions for the pediatric orthopaedic examination. Specific

examination techniques are covered in the chapters that follow.

small adults. The growth and development from infancy to maturity

constitutes a significant difference relative to adults and among

children themselves. Growth should be considered in both your diagnosis

and treatment. Developmental milestones can be screened by the Denver

Developmental Screening Test (DDST). The DDST is a standardized device

used to assess the development of preschool children (Table 1-1).

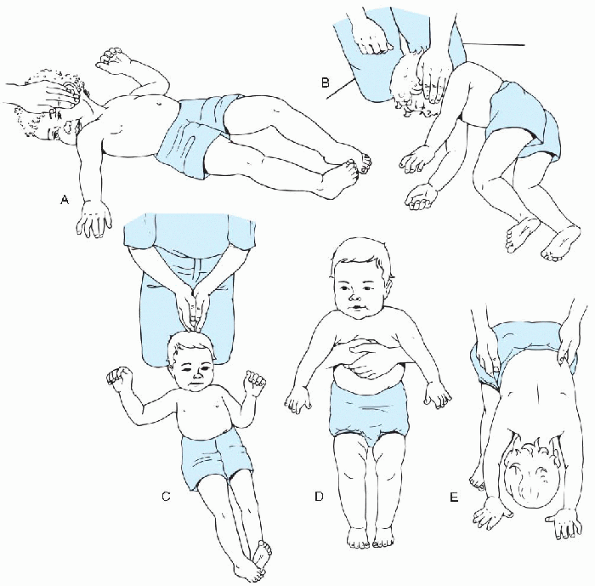

children with the developmental delay seen in cerebral palsy. Primitive

reflexes that persist longer than 3 months of age may indicate a fixed

motor—brain defect (Fig. 1-1). Testing is done

after 12 months of age. If no abnormal responses are seen, there is a

good prognosis that the child will walk. If two or more abnormal

responses are present, there is a poor prognosis that the child will

walk.

successful people is to begin with an end in mind. The goal of the

pediatric orthopaedist is to arrive with a diagnosis. DeGowin and

DeGowin have likened the physician to a detective. You have to gather

information regarding a specific problem (history) and confirm or

disprove your case (diagnosis) by the evidence (examination).

The dynamics of dependence requires your interaction with at least two

individuals, the child and the parent. For consistency, “parent” and

“family” will be used when referring to the child’s caregivers—mother,

father, relative, or guardian. When you first meet the child and

family, greet and identify all individuals in the examination room.

Identify yourself, your role, and what you will be doing. Offer a form

of greeting such as a handshake to include the child. Do what is

natural for you. Wearing a white coat may create anxiety and complicate

your evaluation of the child. Most children have some anxiety, possibly

reinforced by the parent, about a visit to the doctor, and the

formality of a white coat may exacerbate this anxiety. The parent may

claim your white coat is making the situation difficult. Removing your

coat later may not resolve that difficulty.

|

TABLE 1-1 DENVER DEVELOPMENTAL SCREENING TEST

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

Figure 1-1 Testing for cerebral palsy-associated developmental delays. (A)

The asymmetric tonic neck reflex is positive when a fencing posture—flexion of the limbs on the skull side and extension of the limbs on the face side—is assumed on turning the head sharply to one side. This is abnormal after 12 months of age. (B) The neck-righting reflex is positive when the body can be log-rolled by turning only the head. This response is abnormal after 12 months of age. (C) The Moro reflex is positive when there is abduction of the upper limbs followed by an embrace in response to a loud noise, such as a clap of the hands, or to jarring of the table. This is also abnormal after 12 months of age. (D): Extensor thrust is elicited by holding the child upright by the axillae and lowering the feet to the floor or a table surface. Progressive extension of the lower limbs and trunk is abnormal at any age. (E) The protective parachute reaction involves lowering the supine child to the table. Automatic hand placement should be present by at least 15 months of age. Hand withdrawal is never normal. (Adapted from Bleck EE. Cerebral palsy. In: Staheli LT. Pediatric orthopaedic secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1998:348-358.) |

all but the child and his or her primary caregiver(s) from the

examination room (i.e., siblings and other relatives or friends brought

along for moral support). Take the family’s concerns seriously and

listen carefully. Medical evaluation is sought for a problem that needs

to be defined. Common concerns include pain, deformity, clumsiness,

weakness, and stiffness. The history of present illness provides the

background. Try to obtain the chief complaint directly from a

school-age child or adolescent and verify the information with the

parent. The complaint needs to be welldefined (described) including who

has the concern and why. Symptoms can usually be dated to when

something was first thought to be wrong or different. Follow the

history of present illness in a clear, chronologic fashion. Note onset,

setting in which the problem developed, and treatment. Symptoms should

be related to location, severity, timing (onset, duration, frequency),

and what aggravates or remits. Many symptoms are related to

use/overuse/abuse, movement, or injury.

-

Birth history: inquiries of prenatal maternal bleeding, infection, medications, trauma

-

Childbirth delivery information: presentation, type of delivery, difficulty of delivery, infant distress

-

Neonatal information: Apgar scores, need for oxygen/ventilator support, duration of hospitalization

-

Family history: inquiries about the

presence of scoliosis, clubfoot, hip dysplasia, skeletal dysplasia, and

neuromuscular disorders, as well as similar presentation of the chief

complaint.

expectations. Alternative treatments may have been received. Often, the

information will not be volunteered so you must ask about dietary,

herbal, energy, or manipulative interventions.

examination. Shorts and T-shirts appear to be comfortable for children

of all ages and should be readily available. Never miss an opportunity

to examine the child without actually touching. Examine younger

children in while on their parent’s lap. If the parent/caregiver is

absent, have a professional present to observe and chaperone. Observe

action such as gait, mobility, arm swing/preference, guarding,

climbing, and playing. Perform your examination without appearing to do

so. Make your first touch innocuous and nonthreatening in areas you

know do not hurt. If there is resistance, the parent should realize the

difficulty you are facing and observe that any negative response is not

due to pain. By examining the normal, asymptomatic limb first, you will

have a comparison. Minimize discomfort without compromising purpose. If

you are unable to examine, then ask the parent to palpate and perform

motion while you observe. Recognize, and have the parent acknowledge,

when you are unable to get an adequate examination. Do not presume a

finding or give up out of frustration.

Try to agree as much as possible with the parents regarding their

observations when discussing findings. Appear calm and unhurried, even

if that is not the case. Take the time to sit down and discuss the

results of the examination with the child and parent. If the parents

are rushed, they will feel that you have not devoted the appropriate

time or concern. When the problem is complex and needs more time, you

can inform the parents that you will consult with others before you can

provide a definitive answer or plan. Set a specific time for follow-up.

Oftentimes the understanding of the parents may be lacking and

additional visits will be helpful.

inspection, palpation, range of motion, neurologic examination, special

tests, and examination of related areas.

tenderness. Recognize and record deformity and measure with a

goniometer. Deformity is described as the relationship of the distal

segment relative to the proximal. Determine whether the deformity is

bone, joint, or soft tissue. Can the deformity be passively corrected

or is it fixed? Is there associated spasm or tenderness to palpation?

abnormal, then note the demarcation between intact and altered

sensation. Limb tightness can represent contracture or tone

abnormalities. Spastically is a velocity-dependent change in tone. With

fast stretch there is greater resistance than with slow stretch. The

up-going plantar response (Babinski sign) can be normal in 10% of

neonates and persist up to 2 years of age. Three to six beats of ankle

clonus can be found in normal individuals, but sustained ankle clonus

suggests severe central nervous system disease. Abdominal reflexes are

stimulated by gently stroking the abdomen in a lateral-to-medial

direction toward the umbilicus. The reflexes should be present

bilaterally. Unilateral absence is usually associated with some

corticospinal impairment. In children with cerebral palsy, muscle

control rather than strength is assessed because of the inability for

selective motor control. If you find mild spasticity in one limb and

are not sure whether there is hemiplegia, ask the child to run in the

hallway. If there is hemiplegia, one upper limb will have a flexed

posture when running.

-

Metacarpophalangeal dorsiflexion greater than 90 degrees

-

Elbow recurvatum more than 10 degrees

-

Maximum wrist palmar flexion so that the thumb touches the volar forearm

-

Knee recurvatum more than 10 degrees

-

Ankle dorsiflexion greater than 60 degrees.

are not infrequent in children and little is required except to

discourage a voluntary component. Ligament tears are demonstrated by

joint space opening and graded as interstitial (I), partial (II), or

complete (III).

spontaneous and stimulated movement. Spine and skin should be

inspected. Foot position and flexibility should be noted. An algorithm

has been developed for foot deformities

(Algorithm 1-1).

Note whether the forefoot is adducted. If the forefoot is adducted,

then note whether the hindfoot is in varus (clubfoot) or not

(metatarsus adductus). If the forefoot is abducted, then note whether

the hindfoot is in equinus (vertical talus) or not. If the hindfoot is

in calcaneus, then note whether tibial bowing is present or not

(postural calcaneovalgus). Hip instability signs should be assessed by

the Barlow (positive, meaning a reduced hip that is dislocatable) and

Ortolani maneuvers (positive, meaning a dislocated hip that is

reducible).

|

TABLE 1-2 JOINT MOTION AND PRIMARY MOTOR MUSCLE, NERVE, AND ROOT

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

TABLE 1-3 GRADING OF MUSCLE STRENGTH

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Algorithm 1-1

Assessment of foot deformity. (Adapted from Birch JG. Foot deformity. In: Bucholz RW, ed. Orthopaedic decision making, 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1996:242.) |

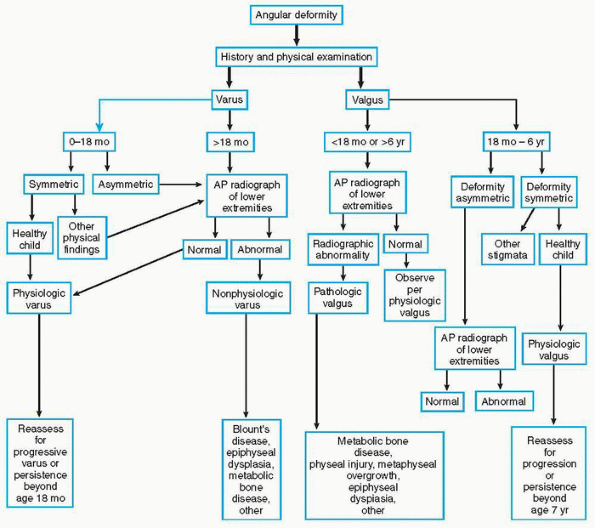

Most angular deformities in the lower extremities are in the knee

region. Children should be assessed relative to age. Varus deformity

(bowleg) is normal between birth and 18 months of age. Varus deformity

that persists after the age of 18 months is asymmetric or is associated

with injury or infection and requires further evaluation. Findings of

poor general health, short stature, and multiple long bone or joint

deformities suggest metabolic disease or dysplasia. Children between 18

months and 6 years of age typically show symmetric genu valgum

(knock-knee). The knock-knee is maximal at 3 to 4 years of age and

assumes the average mature alignment of slight genu valgum by 6 to 7

years of age. If the knock-knee is asymmetric, worsens after 4 years of

age, or is excessive after 7 years of age, then further evaluation is

indicated.

Torsional problems, intoeing and out-toeing, often concern parents and

frequently prompt evaluation. The lower limb rotates medially during

the seventh fetal week to bring the great toe to midline. With growth,

femoral anteversion

decreases

from 30 degrees at birth to 10 degrees at maturity and the tibia

laterally rotates from 5 degrees medial at birth to 15 degrees lateral

at maturity. Lower extremity rotational alignment includes assessment

of walking (foot progression), lateral border of the foot (adducted in

metatarsus adductus), the thigh—foot angle (tibial torsion), and hip

range of motion.

|

|

Algorithm 1-2

Assessment of angular deformity. (Adapted from Birch JG. Angular deformity. In: Bucholz RW, ed. Orthopaedic decision making, 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1996:334.) |

heights and belt line for asymmetry. The iliac crests can be palpated

and visually assessed regarding possible limb length discrepancy. Minor

degrees of body side differences are not unusual. The forward bend test

is performed looking for a thoracic/rib or lumbar prominence. A

scoliometer records asymmetry and can be used for screening.

-

Ask about activities the child enjoys.

-

Avoid threatening words like hurt, cut, and break.

-

Pain is significant in children, especially if it interferes with play or sleep.

-

Muscle pulls are uncommon in children.

-

Check the hip when a child complains of knee or thigh pain.

-

If hip examination and motion are not completely normal, obtain radiographs.

-

Asymmetric hip motion needs further evaluation.

-

Check the spine and perform a neurologic examination with foot deformities, especially unilateral.

-

Check the abdominal reflex in spinal deformity.

-

Treat others as you would like to be treated.

|

|

Algorithm 1-3

Assessment of torsional deformity. (Adapted from Staheli LT. Fundamentals of pediatric orthopaedics. New York: Raven Press, 1992:4-5.) |

examination. Be thorough, be complete, and be focused. Start with the

end in mind. Aspire to be the best you can be and to do good for the

children you treat and their families. This chapter provides

suggestions for the pediatric orthopaedic examination. The diagnostic

chapters that follow will cover examination techniques, workup, and

treatment of specific pediatric orthopaedic disorders.

JA. The orthopaedic examination: a comprehensive overview. In:

Tachdjian’s pediatric orthopaedics, 3rd ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders, 2001:25.

KF. Neurologic examination after the newborn period until two years of

age. In: Pediatric neurology: principles and practice, 2nd ed. Vol 1.

St Louis: Mosby, 1993:43.