Shoulder Anatomy and Examination

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Shoulder Anatomy and Examination

Shoulder Anatomy and Examination

Constantine A. Demetracopoulos BS

Timothy S. Johnson MD

Description

-

Bones:

-

Glenohumeral joint:

-

The humeral head articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

-

Stabilized by the glenohumeral ligaments (1) capsule and rotator cuff muscles

-

The labrum of the glenoid deepens the joint and enhances stability.

-

-

AC joint:

-

The acromion process of the scapula articulates with the distal clavicle.

-

Suspends the arm and scapula

-

-

Sternoclavicular joint:

-

The sternum articulates with the proximal end of clavicle.

-

Suspends the arm and scapula

-

-

Scapulothoracic joint:

-

Consists of the body of the scapula and the muscles covering the posterior chest wall

-

Contributes to shoulder flexion and rotation

-

-

-

Muscles:

-

The trapezius, levator, rhomboids, and serratus anterior stabilize the scapula to aid motion at the glenohumeral joint.

-

Deltoid: Flexor, abductor, and extensor

-

Rotator cuff:

-

Supraspinatus: Abductor and external rotator

-

Infraspinatus: External rotator

-

Teres minor: External rotator

-

Subscapularis: Internal rotator and adductor

-

-

Pectoralis major: Adductor

-

Coracobrachialis and biceps: Flexors

-

-

Nerves:

-

Brachial plexus:

-

Passes through the axilla

-

Branches originate in the neck from C5–T1.

-

-

Axillary nerve:

-

Innervates the deltoid

-

May be injured in anterior shoulder dislocations

-

-

Musculocutaneous nerve: Innervates the biceps and coracobrachialis

-

Signs and Symptoms

History

Thorough history of the mechanism of injury and the nature of pain

Physical Exam

-

Initial assessment:

-

Assess the cervical spine and elbow.

-

Perform a complete neurovascular examination of the extremities.

-

Assess the contralateral shoulder for comparison.

-

-

Inspection:

-

Expose both upper extremities from the shoulder girdle to the hand, inspecting for asymmetry, atrophy, and scapular winging.

-

-

Palpation:

-

Palpate the sternoclavicular joint,

clavicle, AC joint, coracoid, acromion, glenohumeral joint, bicipital

groove, and the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humerus. -

Localize the pain.

-

-

ROM:

-

Compare active and passive ROM.

-

Forward flexion: 180°

-

Extension: 50–60°

-

-

Motion:

-

Assess in adduction and abduction.

-

Distinguish glenohumeral motion from combined glenohumeral and scapulothoracic motion (combined values).

-

External rotation: 80–90°

-

Internal rotation: 60–80°

-

Abduction: 160–180°

-

-

Tests

-

Biceps tendinitis:

-

Pain to palpation in the bicipital groove, found anteriorly on the shoulder with the arm at 10° of internal rotation

-

Yergason test:

-

Test resisted forearm supination with the elbow flexed at 90°.

-

Test is positive when pain is reproduced in the bicipital groove.

-

-

Speed test:

-

With the elbow extended, the forearm

supinated, and the shoulder flexed at 60°, ask the patient to resist

additional forward flexion of shoulder. -

The test is positive when pain is reproduced in the bicipital groove.

-

-

-

Subacromial bursitis:

-

Presentation is very similar to that of rotator cuff tendinitis.

-

Patient may present with subacromial crepitus.

-

-

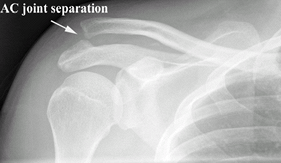

Rotator cuff tear (2) (Fig. 1):

-

Diffuse, dull, aching pain localized over the deltoid and upper arm

-

Pain with overhead activities

-

Tenderness to palpation over the greater tuberosity of the humerus

-

Test individual rotator cuff muscles for weakness and or pain.

-

Supraspinatus: Test the patient’s

strength in active arm elevation in the plane of the scapula with the

patient’s thumb pointing down. -

Infraspinatus and teres minor: Test the

patient’s strength in active external rotation with the patient’s arm

at the side and the elbow flexed at 90°. -

Subscapularis (“belly press” test): Place

both of the patient’s hands on his/her belly; have the patient press

the belly inward while thrusting elbows forward; the test is positive

if the elbow cannot be actively moved forward. Fig. 1. MRI image of a supraspinatus tendon tear.

Fig. 1. MRI image of a supraspinatus tendon tear.

-

-

Neer sign:

-

Elevate the arm while stabilizing the scapula.

-

Positive sign: Pain at maximal elevation

-

-

Hawkins test:

-

With the patient’s elbow flexed at 90°, forward flex the shoulder to 90° and internally rotate the humerus.

-

The test is positive if pain is reproduced on contact of the greater tuberosity with the acromion.

-

-

Painful arc:

-

Active abduction in the coronal plane

-

The test is positive with pain at 60–100° of abduction.

-

Pain is common in tendinitis and small rotator cuff tears

-

-

Drop-arm test:

-

Inability to hold arm up when passively positioned into an elevated position

-

Suggests a large tear

-

-

Weakness, inability to elevate, and passive ROM that exceeds active ROM also suggest rotator cuff tear.

-

Popeye sign:

-

The biceps resembles a “Popeye” muscle when resisted elbow flexion is tested.

-

Indicates a proximal rupture of the biceps tendon

-

Note: Also occurs with distal biceps tendon rupture

-

P.391 -

-

Shoulder instability (3):

-

History of previous dislocations

-

Patient complains of instability with or without pain.

-

Anterior instability: Apprehension with 90/90 positioning (90° of abduction and 90° of external rotation)

-

Posterior instability: Apprehension with humeral forward flexion in internal rotation

-

Load and shift test:

-

With the humerus in a neutral position on the glenoid, axially load the humerus and shift the head anteriorly and posteriorly.

-

Excessive translation resulting in palpable subluxation and/or dislocation is a positive finding.

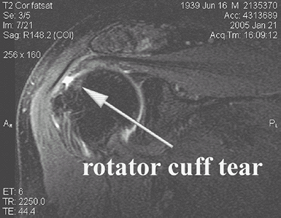

![]() Fig. 2. Radiograph of an AC joint separation.

Fig. 2. Radiograph of an AC joint separation.

-

-

Sulcus sign:

-

With the affected elbow flexed, apply inferior traction to the arm and look for skin dimpling near the lateral acromion.

-

Dimpling indicates inferior instability.

-

-

-

AC joint arthritis/AC separation (4):

-

Palpable point tenderness at the AC joint

-

Palpable step-off at the AC joint in the presence of a separation (Fig. 2)

-

Joint effusion may be present.

-

Cross-body adduction test:

-

With the shoulder at 90° of flexion, passively adduct the arm.

-

The test is positive when pain is reproduced at the AC joint.

-

-

-

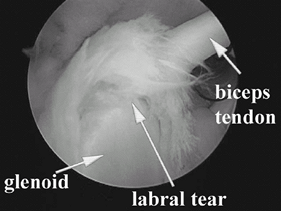

Labrum abnormality (Fig. 3):

-

Patient describes pain as “deep” in the shoulder and occurring with overhead activities.

-

Patient may have anterior or posterior joint line tenderness.

-

Active compression test:

-

Position the affected arm as for the cross-body adduction test.

-

With the elbow extended, and the humerus internally rotated (thumb down), test resisted humeral elevation.

-

Positive test: Pain is elicited when in

internal rotation but relieved when the test is repeated in external

rotation (thumb up). -

Pain localized deep in the shoulder is indicative of biceps or labral abnormality.

-

Pain at the top of the shoulder indicates AC abnormality.

-

Pain elsewhere is equivocal.

-

-

-

Glenohumeral joint arthritis:

-

Start-up pain on initiation of activity

-

Palpable joint-line tenderness

-

Decreased active and passive ROM

-

Active and passive ROM are equal.

-

Pain at the extremes of motion in all planes

-

Glenohumeral crepitus with motion

-

-

Adhesive capsulitis:

-

Palpable joint line tenderness

-

Severely decreased ROM

-

Active and passive ROM are equal.

-

Pain with motion in all planes

Fig. 3. Arthroscopic image of a SLAP tear.

Fig. 3. Arthroscopic image of a SLAP tear.

-

References

1. Curl LA, Warren RF. Glenohumeral joint stability. Selective cutting studies on the static capsular restraints. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;330:54–65.

2. Tennent

TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with

shoulder examination. Part I: the rotator cuff tests. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:154–160.

TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with

shoulder examination. Part I: the rotator cuff tests. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:154–160.

3. Tennent

TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with

shoulder examination. Part II: laxity, instability, and superior labral

anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:301–307.

TD, Beach WR, Meyers JF. A review of the special tests associated with

shoulder examination. Part II: laxity, instability, and superior labral

anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:301–307.

4. Chronopoulos E, Kim TK, Park HB, et al. Diagnostic value of physical tests for isolated chronic AC lesions. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:655–661.

Additional Reading

Hoppenfeld S. Physical examination of the shoulder. In: Physical Examination of the Spine & Extremities. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1976:1–34.

Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P. The shoulder. In: Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomical Approach, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2003:1–66.

FAQ

Q: What are the most common causes of atraumatic shoulder pain?

A: Rotator cuff disease, AC joint arthritis, cervical radiculopathy.

Q: What is the difference between a shoulder separation and a shoulder dislocation?

A: A shoulder separation is a dislocation of the AC joint. A shoulder dislocation is a dislocation of the glenohumeral joint.