Radial Nerve

nerve palsy originating in the arm will be encountered on an upper

extremity service and it is appropriate to discuss it in the context of

this book.

with fractures of the humerus in the middle third or at the junction of

the middle and distal thirds. Radial nerve palsy at this location is

distinguished from the more proximal “Saturday night palsy” and “crutch

palsy” seen in the upper arm and axilla, respectively. These more

proximal lesions usually recover spontaneously in 60 to 90 days and are

not the topic of discussion here.

-

The proximity of the radial nerve to bone in the spiral groove.

-

The relative fixation of the radial nerve

in the spiral groove and at the site of penetration of the nerve

through the lateral intermuscular septum on its way from the posterior

to the anterior aspect of the arm.

postulate the etiology of the neurapraxia based on traction, contusion,

or hematoma.

issue of early versus late exploration of radial nerve palsy associated

with humeral fracture, most palsies recover spontaneously, and early

surgical exploration is recommended in only three circumstances: (1)

open fractures, (2) fractures that require open reduction and or

fixation, and (3) fractures with associated vascular injuries. The

onset of radial nerve palsy after fracture manipulation is not an

indication for early nerve exploration

fracture of the distal humerus in seven patients, five with radial

nerve paralysis and two with paresis. They noted radial angulation and

overriding at the fracture site. As the radial nerve courses anteriorly

through the lateral intermuscular septum, it is less mobile and subject

to being injured by the movement of the distal fracture fragment.

Because of the high incidence of radial nerve dysfunction, early

operative intervention was advised.

trauma-related palsy. A fibrous arch and accessory part of the lateral

head of the triceps has been associated with nerve compression

secondary to swelling of the muscle after muscular effort. Some cases

of radial nerve entrapment in this region of the lateral head of the

triceps have been reported as spontaneous in onset and some following

strenuous muscular activity. What appears to be a familial radial nerve

entrapment syndrome has been reported in a 15-year-old girl with a

total and spontaneous radial nerve palsy. Her sister had recently

sustained an identical lesion that improved spontaneously, and her

father also suffered from intermittent radial nerve palsy. These cases

appear to represent a genetically determined defect in Schwann cell

myelin metabolism.

-

Although a patient with entrapment

neuropathy with an acute onset after overactivity sometimes recovers

spontaneously, entrapment in the advanced stage should be surgically

decompressed because prolonged compression might result in intraneural

fibrotic changes secondary to long-term compression. -

The surgical approach of choice is posterior between the long and lateral heads of the triceps.

superficial radial nerve at the wrist that he called cheiralgia

paresthetica. The condition is characterized by pain, burning, or

numbness on the dorsal and radial aspect of the distal forearm and

wrist that radiates into the thumb, index, and middle fingers. The

symptoms are often associated with a history of a variety of traumatic

and iatrogenic causes, including a direct blow to the nerve, a tight

wristwatch band or bracelet, handcuffs, or an injury due to laceration

or compression from retraction during surgery. Although Wartenberg

classified it as “neuritis,” it is a form of nerve entrapment

positioned beneath the BR muscle as it travels towards the wrist, where

it exits from beneath the BR tendon and between the ECRL tendon to

pierce the antebrachial fascia. In 10% of specimens, the nerve may

pierce the tendon of the BR. It becomes subcutaneous at a mean of 9 cm

(with a range of 7 to 10.8 cm) proximal to the radial styloid. In

supination the SBRN lies beneath the fascia, but without compression.

In pronation, the ECRL crosses over the BR and may create a scissoring

or pinching effect on the SBRN.

-

A useful provocative test is to ask the

patient to fully pronate the forearm. A positive test is manifested by

paresthesia or dysesthesia on the dorsoradial aspect of the hand. -

In addition to this provocative test, a

positive Tinel’s sign may be noted over the nerve distal to the BR

muscle belly as well as altered moving touch and vibratory sense.

-

Treatment is based on the particular

cause, and is usually conservative in the form of splinting, altered

physical activities, and physical therapy including stretching and

tissue gliding exercises. -

In patients who require surgery, release

of the deep fascia and the fascia joining the BR and ECRL, as well as

neurolysis of the SBRN, may be utilized in selected cases.

through the spiral groove to enter the anterolateral aspect of the

distal third of the arm on its way to the forearm, where it lies

between the brachioradialis laterally and the brachialis medially. The

ECRL covers it anterolaterally, and the capitellum of the humerus is

posterior. The radial tunnel begins at the level of the radiohumeral

joint and extends through the arcade of Frohse to end at the distal end

of the supinator. Division of the radial nerve into motor (posterior

interosseous) and sensory (superficial radial) components may occur at

any level within a 5.5-cm segment, from 2.5 cm above to 3 cm below

Hueter’s or the interepicondylar line (a line drawn through the tips of

the epicondyles of the humerus). The superficial radial nerve remains

on the underside of the brachioradialis until it reaches the

mid-portion of the forearm and is not subject to compression in the

radial tunnel

(the distal border). The fibrous bands are anterior to the radial head

at the beginning of the radial tunnel, and are the least likely cause

of compression. The radial recurrent vessels cross the PIN to supply

the adjacent brachioradialis and ECR muscles, and it is postulated that

engorgement of these vessels with exercise may compress the nerve. The

tendinous proximal margin of the ECRB also may compress the PIN, and

may be mistakenly identified as the arcade of Frohse, which lies deep

to the proximal margin of the ECRB muscle. The arcade of Frohse is the

fibrous proximal border of the superficial portion of the supinator. It

is the most common site of compression of the PIN, and is located from

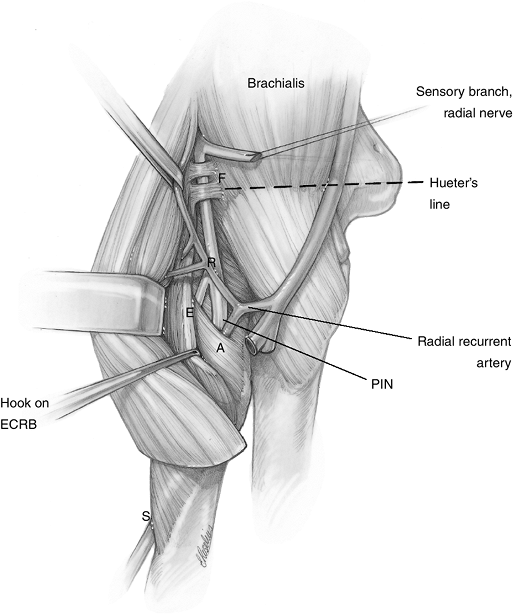

3 to 5 cm below Hueter’s line (Figure 7.3-2).

Sometimes the tendinous margin of the ECRB and the arcade of Frohse may

overlap and form a scissors-like pincer effect on the radial

nerve

in this area. It is appropriate to continue the exploration to the

distal border of the supinator, although it is a rare site of

compression. More often, a mass, such as a ganglion, may be found

beneath the superficial portion of the supinator.

|

|

Figure 7.3-1

Potential sites of compression of the radial nerve in radial tunnel syndrome (RTS). F, fibrous tissue bands; R, radial recurrent vessels; E, fibrous edge of ECRB; A, arcade of Frohse; S, supinator (see text). |

|

|

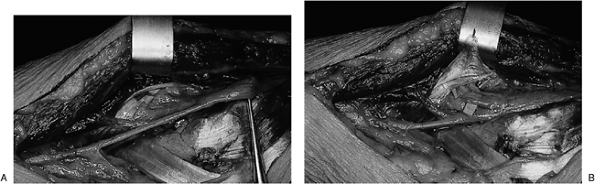

Figure 7.3-2 Fresh cadaver dissection of the ECRB and supinator. (A) The fibrous tissue edges of the ECRB and the supinator are in close proximity to the PIN as it enters the supinator. (B)

The ECRB has been reflected superiorly. Fat has been removed from around the supinator to reveal its two heads and to reveal the fibrous tissue edge of the superficial head that forms the arcade of Frohse. |

-

The radial tunnel syndrome (RTS) must be distinguished from PIN syndrome (PINS).

-

RTS is a subjective symptom complex

without motor deficit, which involves a motor nerve. This is in

contrast to PINS, which is an objective complex with motor deficit

affecting a motor nerve. -

The symptoms in RTS are similar to

lateral epicondylitis, with complaints of pain over the lateral aspect

of the elbow that sometimes radiates to the wrist. Because compression

of a motor nerve is believed to cause the pain, the description of the

pain as a deep ache is not surprising. -

A dynamic state may exist in which

pronation, elbow extension, and wrist flexion are combined with

contraction of the wrist and finger extensors to produce compression of

the PIN.

-

-

Physical findings may include point tenderness 5 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle.

-

The absence of sensory or motor disturbances in RTS is characteristic.

-

To a limited extent, provocative tests

may give some indication of the anatomic location of the compression,

but are not always reliable. -

The so-called middle finger test involves

extension of the middle finger with the elbow in extension and the

wrist in neutral. The test is considered to be positive if pain is

produced in the region of the proximal portion of the ECRB. Sanders has

modified this test as follows:-

With the elbow in full extension, the

forearm in full pronation, and the wrist held in flexion by the

examiner, the patient is asked to actively extend the long and ring

fingers against resistance. -

According to Sanders, these positional

modifications produce maximum compression on the PIN, and represent a

more reliable form of the test. -

If symptoms are reproduced with the elbow

in full flexion, the forearm in supination, and the wrist in neutral,

then fibrous bands are suspected. -

Reproduction of symptoms by passive

pronation of the forearm—with the elbow in 45 to 90 degrees of flexion

and the wrist in full flexion—indicates entrapment by the ECRB. -

Compression at the arcade of Frohse is

suspected if the symptoms are reproduced by isometric supination of the

forearm in the fully pronated position.

-

-

The most reliable test is the injection

of 2 to 3 mL of 1% lidocaine without epinephrine into the radial

tunnel. Relief of pain and a PIN palsy confirms the diagnosis. -

A prior injection into the lateral epicondylar region that did not relieve pain also supports the diagnosis.

-

Electrodiagnostic studies to date have

not been useful in the diagnosis because there are no motor deficits,

and studies of conduction velocity through the radial tunnel are

unreliable.

-

Treatment may be nonoperative, in the

form of rest to the extremity and avoidance of the activities that

aggravate the condition. -

The judicious injection of steroids about the site or sites of possible compression may result in some relief.

-

Surgical intervention is in the form of release of all possible points of compression of the nerve.

motor signs of entrapment of the PIN manifested by weakness or complete

palsy of the finger and thumb extensors. There usually is no history of

antecedent trauma.

-

In complete PINS, active extension of the

wrist occurs with radial deviation owing to loss of the ECRB, whereas

the more proximally innervated ECRL remains intact. -

There is associated loss of finger and thumb extension.

-

Partial loss of function is more common, with lack of extension of one or more fingers or isolated loss of thumb extension.

-

Sensation always is intact.

-

In contrast to RTS, EMG is positive in the muscles innervated by the PIN.

-

Computed tomography scans or magnetic resonance imaging may show a mass in the radial tunnel.

-

The nerve should be explored from the arm

to the distal aspect of the supinator, based upon the clinical findings

and the findings at surgery.

digital nerve of the thumb. It results from external pressure from the

margin of the thumb hole in a bowling ball. It usually involves the

ulnar nerve, and is characterized by pain, paresthesias, and a tender

mass on the ulnar aspect of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. A

variation known as cherry pitter’s thumb has been described by Viegas.

-

Both conditions may be treated by

activity modification, and, in the case of bowler’s thumb, by enlarging

the thumb hole in the bowling ball.

R, Meunier M. Chapter 21. Carpal tunnel syndrome. In: Trumble, TE, ed.

Hand surgery update 3, hand, elbow & shoulder. Rosemont, IL:

American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 2003:299–312.

AL, Chiu DTW. Chapter 22. Cubital and radial tunnel syndromes. In:

Trumble, TE, ed. Hand surgery update 3, hand, elbow & shoulder.

Rosemont, IL: American Society for Surgery of the Hand, 2003:313–323.

AL. Diagnosis and treatment of ulnar nerve compression of the elbow.

Techniques in Hand and Upper Extremity Surgery 2000;4:127–136.

JH, O’Brien ET, Linscheid RL, et al. Bowler’s thumb: diagnosis and

treatment. A review of seventeen cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1972;54:751.

JR, Botte MJ. Elbow. In: Surgical anatomy of the hand and upper

extremity. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams,

2002:365–406.

JR, Botte MJ. Forearm. In: Surgical anatomy of the hand and upper

extremity. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams,

2002:407–485.

JR, Botte MJ. Palmar hand. In: Surgical anatomy of the hand and upper

extremity. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams,

2002:532–641.

W, Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Cheiralgia paresthetica (entrapment of the

radial sensory nerve). J Hand Surg 1986;11:196–199.