Other Tumors of Undefined Neoplastic Nature

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.8 – Other Tumors of Undefined Neoplastic Nature

II – Specific Bone Neoplasms and Simulators > 5 – Benign Bone Tumors

> 5.8 – Other Tumors of Undefined Neoplastic Nature

5.8

Other Tumors of Undefined Neoplastic Nature

Sean V. McGarry

C. Parker Gibbs

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and Erdheim-Chester

disease (ECD) are histiocytoses: rare benign lesions of bone in which

the proliferating tumor cell of origin is a histiocyte. There are two

types of histiocytes: (1) macrophages arising from monocytes and (2)

dendritic cells arising from Langerhans cells. In LCH the involved cell

is a Langerhans cell, in ECD a macrophage. Histiocytoses in general

exist in multiple forms, ranging from a solitary lesion to a diffuse

systemic disease, and they can affect any organ or tissue in the body.

This section deals with the two histiocytoses involving bone: LCH and

ECD. LCH is most commonly a solitary lesion occurring in children and

young adults and often requires surgical intervention. ECD is often a

systemic disease of older adults and very rarely involves surgical

intervention.

disease (ECD) are histiocytoses: rare benign lesions of bone in which

the proliferating tumor cell of origin is a histiocyte. There are two

types of histiocytes: (1) macrophages arising from monocytes and (2)

dendritic cells arising from Langerhans cells. In LCH the involved cell

is a Langerhans cell, in ECD a macrophage. Histiocytoses in general

exist in multiple forms, ranging from a solitary lesion to a diffuse

systemic disease, and they can affect any organ or tissue in the body.

This section deals with the two histiocytoses involving bone: LCH and

ECD. LCH is most commonly a solitary lesion occurring in children and

young adults and often requires surgical intervention. ECD is often a

systemic disease of older adults and very rarely involves surgical

intervention.

Erdheim-Chester Disease

The original description of ECD was made by Chester in

1930. In 1972, Jaffe first used the eponym ECD to recognize that

description. In 1983, a review of the literature by Alper found that 47

cases had been described up to that point. ECD remains an extremely

rare entity; thus, our knowledge of the natural history of the disease

and its treatment is somewhat limited. Its etiology is unknown.

1930. In 1972, Jaffe first used the eponym ECD to recognize that

description. In 1983, a review of the literature by Alper found that 47

cases had been described up to that point. ECD remains an extremely

rare entity; thus, our knowledge of the natural history of the disease

and its treatment is somewhat limited. Its etiology is unknown.

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

-

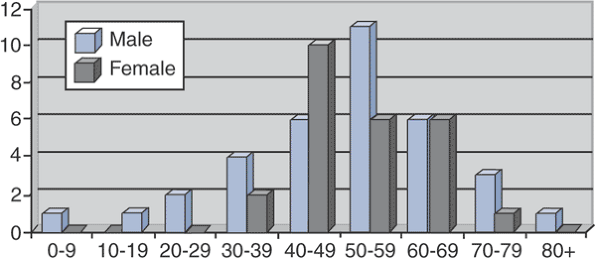

Typically a disease of older adults (Fig. 5.8-1)

-

Age range 7 to 84 years

-

Mean age 53 years

-

-

Slight male predominance

-

Affects long bones most commonly

-

Bilateral and symmetric

-

Classically affects diaphysis and metaphysis, sparing epiphysis (not always)

-

Lower extremity (femur, tibia, fibula) more common than upper extremity (humerus, radius, ulna)

-

-

Usually spares flat bones

Pathophysiology

-

Systemic lipid storage disorder affecting histiocytes

-

Lipid-laden histiocytes form granulomas in bones, other organs or tissues.

Prognosis and Natural History

-

Because of the infrequency of the disease, little is known about prognostic factors.

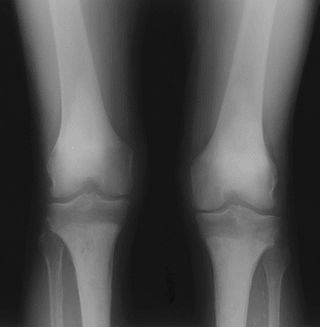

Figure 5.8-1

Figure 5.8-1

Sex and age at time of diagnosis for 59 patients with Erdheim-Chester

disease. (After Veyssier-Belot C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, et al.

Erdheim-Chester disease: Clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59

cases. Medicine 1996;75:157–169.) -

Prognosis is related to extent of visceral involvement.

-

In some patients the disease is quiescent.

-

In most patients the disease is progressive, and patients die of end-organ failure

-

Respiratory distress or pulmonary fibrosis

-

Heart failure

-

Renal failure

-

-

P.171

Classification

-

There currently is no accepted classification scheme for ECD.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination and History

-

A definitive diagnosis requires the combination of history, physical examination findings, radiographs, and a tissue diagnosis.

-

Classical radiographic findings with

bilateral, symmetric osteosclerosis of the diaphysis and metaphysis

with epiphyseal sparing can be considered pathognomonic.

Clinical Features

-

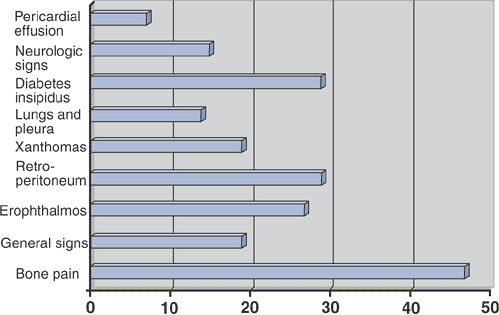

Depends on the organ systems affected (Table 5.8-1 and Fig. 5.8-2)

Radiologic Features

-

Densely sclerotic changes of the metaphysis and diaphysis, with coarsened trabeculae

-

Typically spares the epiphysis

-

Rarely, lesions are more lytic in nature.

-

-

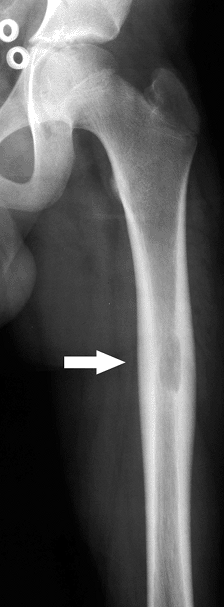

Long bones most commonly affected (Fig. 5.8-3)

-

Lower extremities more commonly affected than upper extremities

-

|

Table 5.8-1 Clinical Manifestations of Erdheim-Chester Disease According to Organ of Involvement

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Figure 5.8-2

Prevalence of clinical signs in 59 patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. (After Veyssier-Belot C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: Clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medicine 1996;75:157–169.) |

Diagnostic Workup Algorithm

-

Radiographs are nearly always pathognomonic for ECD.

-

When seen in concert with typical

complaints of bone pain, exophthalmos, diabetes insipidus, or

xanthomas, these patients are not a diagnostic challenge. -

They can show elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, alkaline phosphatase, or serum lipid profiles.

-

However, laboratory testing is unreliable and nonspecific.

Figure 5.8-3 Radiograph of patient with Erdheim-Chester disease showing typical radiographic changes.

Figure 5.8-3 Radiograph of patient with Erdheim-Chester disease showing typical radiographic changes. -

-

If there is any question as to the diagnosis, a biopsy of an accessible skeletal lesion is performed.

-

Histopathologic evaluation demonstrates

infiltration of the bone by foamy, lipid-laden histiocytes, with giant

cells and rare lymphocytes. -

Immunostaining demonstrates negative staining for both S-100 and CD1a (which would suggest the diagnosis of LCH).

-

P.172

Treatment

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

-

Occasional need for biopsy to confirm diagnosis

-

No need for surgical intervention other than rare prophylactic fixation to prevent fracture

-

No good nonoperative treatment options, but historically patients are treated with any combination of the following:

-

Steroids

-

Chemotherapy

-

Radiation

-

Results and Outcome

Overall Outcome

With no good treatment options for ECD, overall survival

is rather bleak. In a review of 37 patients followed for an average of

30 months, Veyssier-Belot reported a mortality rate of 59%. Other

reports suggest a mortality rate of approximately 33%, but with limited

follow-up. Patients die of end-organ failure (pulmonary fibrosis, heart

failure, or renal failure most commonly).

is rather bleak. In a review of 37 patients followed for an average of

30 months, Veyssier-Belot reported a mortality rate of 59%. Other

reports suggest a mortality rate of approximately 33%, but with limited

follow-up. Patients die of end-organ failure (pulmonary fibrosis, heart

failure, or renal failure most commonly).

Specific Treatment Outcome

Because there is not a consensus as to the appropriate

treatment of ECD in combination with the rarity of the diagnosis, there

are not sufficient numbers to assess specific treatment outcomes. In

the review by Veyssier-Belot, the following results are presented:

treatment of ECD in combination with the rarity of the diagnosis, there

are not sufficient numbers to assess specific treatment outcomes. In

the review by Veyssier-Belot, the following results are presented:

-

Steroid therapy alone in 12 patients

-

Effective transiently in 4 patients

-

Ineffective in 8

-

-

Chemotherapy in combination with steroids in 8 patients

-

4 patients improved

-

No effect in 4 patients

-

-

Radiation therapy in 6 patients

-

Transiently effective in 3 for bone pain

-

Not effective in 3 to treat exophthalmos

-

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

In 1953, Lichtenstein, noting the histological

similarities in eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Christian-Schüller, and

Letterer-Siwe, coined the term “histiocytosis X” as a general term to

encompass all three diagnoses. We know today that all three diseases

originate from a Langerhans cell and refer to the group of disorders as

the Langerhans cell histiocytoses (LCH) or granulomatoses. The three

share a common histopathology and are considered to be clinical

variations of the same disease.

similarities in eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Christian-Schüller, and

Letterer-Siwe, coined the term “histiocytosis X” as a general term to

encompass all three diagnoses. We know today that all three diseases

originate from a Langerhans cell and refer to the group of disorders as

the Langerhans cell histiocytoses (LCH) or granulomatoses. The three

share a common histopathology and are considered to be clinical

variations of the same disease.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

-

Unknown

-

Possibly autoimmune

-

Possibly viral infection

-

Epidemiology

Eosinophilic Granuloma

-

Solitary or multiple lesions of bone, but most commonly solitary (80%)

-

Age and gender

-

Can occur at any age

-

Most patients are between 5 and 20.

-

Male:female ratio 2:1

-

-

Location

-

Flat bones > long bones

-

Skull, pelvis, ribs, spine (anterior column)

-

In long bones, occurs in diaphysis and metaphysis

-

Rare in hands, feet, posterior column of spine, epiphysis of long bones

-

Hand-Christian-Schüller

-

Disseminated, more severe

-

Three names (Hand-Christian-Schüller): think clinical triad:

-

Bone lesions (usually skull)

-

Exophthalmos

-

Diabetes insipidus

-

-

Age and gender

-

Most <5 years

-

Male:female closer to 1:1 than solitary eosinophilic granuloma

-

-

Location

-

Multifocal

-

Very common in skull and jawbones

-

Can occur in hands, feet

-

Letterer-Siwe

-

Disseminated, nearly always fatal

-

Extensive cutaneous lesions

-

Hepatosplenomegaly

-

Fevers/infections

-

-

Age/gender

-

Nearly all <2 years (two names [Letterer-Siwe]: think 2 years)

-

-

Location

-

Ends up involving nearly the entire skeleton

-

Pathophysiology

-

The reticuloendothelial system is a key component of the immune system involved in phagocytizing foreign material and debris.

-

Langerhans cells are an important part of that system.

-

They originate in the bone marrow and then move to the lymph nodes, liver, lung, spleen, and skin.

-

LCH is a proliferation of these cells.

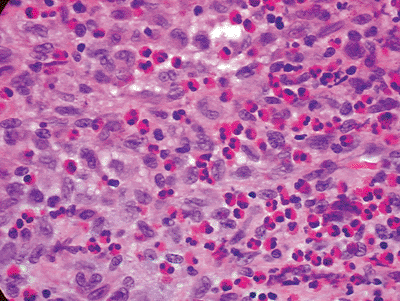

![]() Figure 5.8-4

Figure 5.8-4

Typical histopathology section from bony LCH lesion shows the key

langerhans histiocytes (large, basophilic, cleared, coffee-bean shaped

nuclei) and eosinophils. -

-

This is followed by a granulomatous reaction by the body, with the characteristic eosinophilic cell population.

-

It is the Langerhans cell that is

required for the histological diagnosis, not the ubiquitous eosinophil,

making the name “eosinophilic granuloma” a bit of a misnomer.

P.173

|

Table 5.8-2 Staging System for Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

-

Solitary lesions of eosinophilic granuloma are staged as benign bone tumors.

-

Latent

-

Active

-

Aggressive

-

-

LCH defies most conventional bone tumor classification schemes (Table 5.8-2).

Diagnosis

Physical Examination and History

-

Physical examination and history can vary greatly with LCH, based on the subtype.

-

Often in Hand-Christian-Schüller or

Letterer-Siwe, the patient has already been given a diagnosis by the

pediatrician before he or she is referred to the orthopaedic surgeon. -

A history of localized or referred pain often results from a solitary bone lesion.

-

Patients may also be asymptomatic, the lesions being discovered incidentally on radiographs done for other reasons.

P.174

Clinical Features

Eosinophilic Granuloma

-

Typically patients present with localized bone pain.

-

Occasionally referred pain from a proximal site

-

Example: knee pain with normal x-ray, get hip x-ray

-

-

Younger patients may present with limp or refusal to bear weight.

Hand-Christian-Schü

-

Classic triad is not all that classic (only 10% to 20%).

-

Bone lesions (typically skull)

-

Exophthalmos

-

Diabetes insipidus

-

Letterer-Siwe

-

Bone lesions are not the typical initial presentation.

-

Fevers/infections

-

Exophthalmos

-

Hepatosplenomegaly

-

Lymphadenopathy

-

Cutaneous lesions

-

Papular rash

-

Radiologic Features

Eosinophilic Granuloma

-

Destructive, poorly marginated, lucent lesions (Fig. 5.8-5)

-

One of the “great mimickers,” along with osteomyelitis (Fig. 5.8-6)

-

Usually based in the medullary canal

-

Later or healing lesions may have a cortical rim (Fig. 5.8-7).

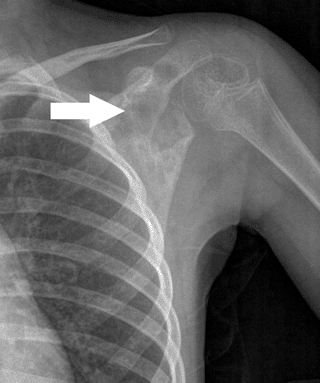

Figure 5.8-5 A destructive poorly marginated lesion in the scapula of a 5-year-old girl.

Figure 5.8-5 A destructive poorly marginated lesion in the scapula of a 5-year-old girl.![]() Figure 5.8-6 Note the radiolucent nature of eosinophilic granuloma in this femoral lesion found in a 12-year-old boy.

Figure 5.8-6 Note the radiolucent nature of eosinophilic granuloma in this femoral lesion found in a 12-year-old boy. -

When they occur in flat bones, they may resemble Ewing sarcoma.

-

-

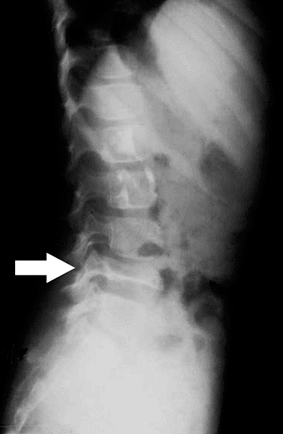

Vertebral body involvement

-

Vertebra plana (Fig. 5.8-8)

-

-

Occasionally larger lesions show cortical

destruction and periosteal reaction (resembling osteosarcoma, Ewing

sarcoma, or osteomyelitis) (Fig. 5.8-9).

Hand-Christian-Schüller

-

Radiographically similar to eosinophilic granuloma lesions

-

Multiple

-

Larger

-

May have a bubbly appearance as lesions overlay

-

Diagnostic Workup

-

Work-up of a patient with lucent lesion suspicious for eosinophilic granuloma

-

Orthogonal radiographs

-

Possibly axial imaging (computed tomography [CT]/magnetic resonance imaging [MRI])

-

Bone scan or skeletal survey to rule out

polyostotic disease, based on other symptoms or clinical suspicion for

polyostotic disease. However, approximately 30% of the lesions do not

show increased uptake on bone scan, making bone scan less reliable than

skeletal survey. -

Biopsy

-

|

|

Figure 5.8-8 Radiographic findings of vertebra plana. Arrow indicates a flattened L4 vertebrae, secondary to eosinophilic granuloma.

|

Treatment

Surgical Indications/Contraindications

-

Usually biopsy is required to rule out other more serious diagnoses on the differential

-

Ewing sarcoma

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Osteosarcoma

-

Leukemia/lymphoma

-

-

Once a diagnosis is made, surgical indications depend on symptoms, location, size, and number of lesions.

-

Painful solitary lesions may warrant a curettage and bone graft, particularly if able to be done coincident with an open biopsy.

-

Impending pathologic fractures should be considered for curettage and prophylactic stabilization.

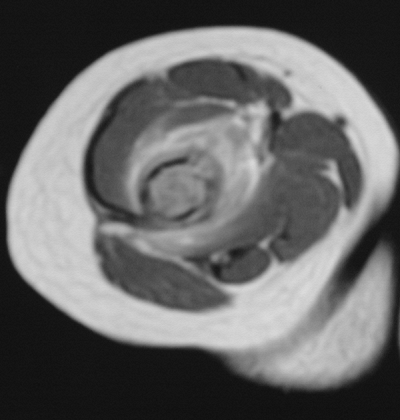

Figure 5.8-9 Axial cut of a T2-weighted MRI image showing extensive edema in the soft tissue of this distal humeral lesion.

Figure 5.8-9 Axial cut of a T2-weighted MRI image showing extensive edema in the soft tissue of this distal humeral lesion. -

Numerous small lesions

(Hand-Christian-Schüller or Letterer-Siwe) typically don’t require

surgery but will require chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. -

Some authors have suggested the use of corticosteroid injection, but with mixed results.

P.176 -

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

-

Surgical

-

Biopsy

-

Curettage/bone graft

-

Prophylactic stabilization

-

Aspiration and steroid injection

-

-

Chemotherapy (for multiple or resistant lesions)

-

Vinblastine

-

Etoposide

-

Prednisone

-

Methotrexate

-

6-mercaptopurine

-

-

Radiation therapy

-

Consider for vertebral lesions at risk of collapse.

-

Establish diagnosis first (usually CT-guided needle biopsy) to avoid mistreatment of Ewing sarcoma or lymphoma.

-

Low dose (500 to 800 cGy)

-

-

Other inaccessible symptomatic lesions

-

Preoperative Planning

-

Plan biopsy tract.

-

Consider surgical adjuvant (phenol,

liquid nitrogen, or argon-beam coagulation). This theoretically offers

a lower recurrence rate, although most reports in the literature are

small series or case reports.

Surgical Goals, Techniques, and Approaches

-

Depend on location, size, symptoms

-

Intralesional curettage with or without surgical adjuvant vs. aspiration and steroid injection

Complications

-

Degenerative changes can occur in periarticular lesions that have been curettaged; consider an adjuvant.

-

Neurologic symptoms in vertebral lesions

-

Pathologic fracture

Results and Outcome

-

Results and outcome vary significantly based on extent of systemic involvement.

Solitary Eosinophilic Granuloma

-

Solitary eosinophilic granuloma will occasionally heal on its own.

-

When it does not, simple curettage and bone graft is usually curative, with a low recurrence rate.

-

Almost all solitary lesions ultimately heal.

-

Usually the reason to treat it surgically is to establish the diagnosis and rule out a malignant diagnosis.

Systemic Disease

-

Results and outcome for systemic disease not as good

-

Because of the rarity of the disease and

the lack of standardized protocols, there are not many reports in the

literature on outcome other than case reports. -

Age of diagnosis is a significant prognostic indicator.

-

Diagnosis at 2 years of age or younger (typically Letterer-Siwe): 10-year survival 42%

-

Diagnosis in patients >2 years of age (usually Hand-Christian-Schüller): 85% 10-year survival

-

-

Patients who survived had higher

incidence of developmental delays, mental retardation, and secondary

malignancies, though these data were from patients treated from 1941 to

1975, and chemotherapy and radiation therapy have improved considerably

since that time.

Postoperative Management

-

Anatomic location dictates the need for protected weight bearing.

-

Patients with solitary lesions of eosinophilic granuloma should be followed closely until the lesion heals.

-

After the lesion heals, these patients are followed by routine surveillance to rule out recurrence.

-

-

Patients treated with low-dose radiation

are at an extremely low risk of radiation-induced sarcoma, but this

should be kept in mind. -

Patients with Hand-Christian-Schüller or

Letterer-Siwe will require pediatric oncology to manage their

chemotherapy and course of their disease.

Suggested Reading

Alper MG, Zimmerman LE, Piana FG. Orbital manifestations of Erdheim-Chester disease. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1983;81:64–85.

Azouz

EM, Saigal G, Rodriguez MM, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis:

pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:103–115.

EM, Saigal G, Rodriguez MM, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis:

pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:103–115.

Cline MJ. Histiocytes and histiocytosis. Blood 1994;84:2840–2853.

Fernando

Ugarriza L, Cabezudo JM, Porras LF, et al. Solitary eosinophilic

granuloma of the cervicothoracic junction causing neurological deficit.

Br J Neurosurg 2003;17:178–181.

Ugarriza L, Cabezudo JM, Porras LF, et al. Solitary eosinophilic

granuloma of the cervicothoracic junction causing neurological deficit.

Br J Neurosurg 2003;17:178–181.

Globerman H, Burstein S, Girardina PJ, et al. A xanthogranulomatous histiocytosis in a child presenting with short stature. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1991;13:42–46.

Greenberger JS, Crocker AC, Vawter G, et al. Results of treatment of 127 patients with systemic histiocytosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1981;60:311–338.

Lichtenstein

L. Histiocytosis X: integration of eosinophilic granuloma of bone,

Letterer-Siwe disease, and Schuller-Christian disease as related

manifestations of a single nosologic entity. AMA Arch Pathol 1953;56:84–102.

L. Histiocytosis X: integration of eosinophilic granuloma of bone,

Letterer-Siwe disease, and Schuller-Christian disease as related

manifestations of a single nosologic entity. AMA Arch Pathol 1953;56:84–102.

Miller RL, Sheeler LR, Bauer TW, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med 1986;80:1230–1236.

Mirra JM. Bone Tumors, 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1989.

Resnick D, Greenway G, Genant H, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease. Radiology 1982;142:289–295.

Unni KK. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996.

Veyssier-Belot

C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease.

Clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:157–169.

C, Cacoub P, Caparros-Lefebvre D, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease.

Clinical and radiologic characteristics of 59 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:157–169.

Waite

RJ, Doherty PW, Liepman M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with

the radiographic findings of Erdheim-Chester disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;150:869–871.

RJ, Doherty PW, Liepman M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis with

the radiographic findings of Erdheim-Chester disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;150:869–871.