Open Fractures

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Cramer, Kathryn E.; Scherl, Susan A.

Title: Pediatrics, 1st Edition

Copyright ©2004 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section II: – Emergency Department > 14 – Open Fractures

14

Open Fractures

Kathryn E. Cramer

Open fractures in children are a heterogenous group of

injuries. While the goals of treatment are similar to those in adults,

the methods used to achieve these goals may differ. Children heal more

quickly, have significant remodeling potential, and generally have

fewer premorbid conditions than adults. However, open physes and size

limitations preclude many of the fixation options available for adult

fractures.

injuries. While the goals of treatment are similar to those in adults,

the methods used to achieve these goals may differ. Children heal more

quickly, have significant remodeling potential, and generally have

fewer premorbid conditions than adults. However, open physes and size

limitations preclude many of the fixation options available for adult

fractures.

PATHOGENESIS

Etiology

-

Occur as a result of higher energy injuries

-

Associated injuries seen in 25% to 75% of children with open fractures

-

Motor vehicle accidents, pedestrians/bicyclists hit by vehicles, and falls are common causes.

-

10% of all polytraumatized children have open fractures.

Epidemiology

-

While pediatric fractures are extremely common, open fractures fortunately account for only 2% of the total.

-

Higher energy trauma results in higher grade injuries.

Pathophysiology

-

Higher energy required to cause an open fracture results in increased comminution and soft tissue stripping.

-

Communication with the external environment allows foreign material and bacteria to contaminate the fracture site.

-

Necrotic soft tissue and bone are easily

infected and poor antibiotic penetration in these areas makes

controlling any infection difficult. -

Fracture stabilization of unstable fractures prevents further soft tissue damage, and allows for neovascularization and healing.

Classification

Open fractures in children are classified by the same system used in adults (Gustilo classification) (Table 14-1).

DIAGNOSIS

Physical Examination and History

History

-

Mechanism

-

Time of injury

-

Medical history

-

Tetanus immunization

Physical Examination

-

Head-to-toe evaluation of entire patient to rule out other injuries—remember your ABCs!

-

Detailed evaluation of injured extremity, including skin condition

-

□ Neurologic exam

-

□ Vascular exam

-

□ Size and configuration of wound

-

□ Amount of contamination

-

□ Tissue pressure measurements if compartment syndrome suspected

-

-

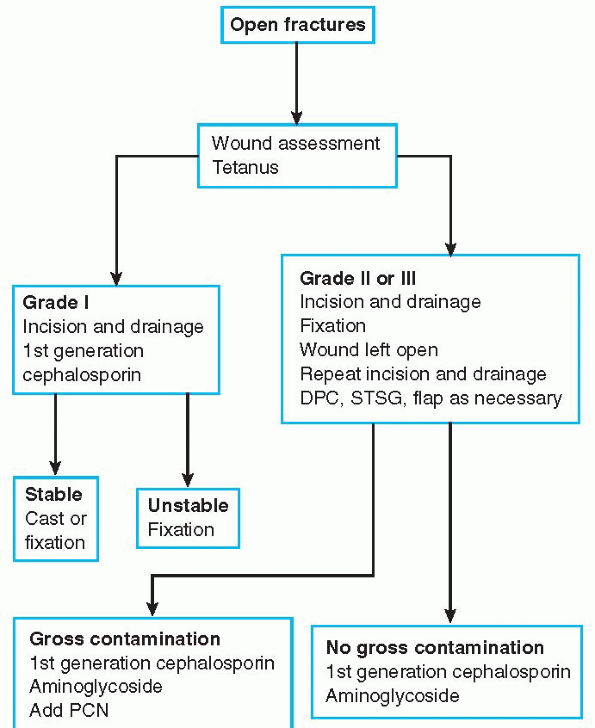

The diagnostic workup of open fractures is considered in Algorithm 14-1.

|

TABLE 14-1 CLASSIFICATION OF OPEN FRACTURES

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.178

|

|

Algorithm 14-1 The diagnostic workup of open fractures in children.

|

Treatment

Treatment begins in the emergency department.

-

Antibiotics:

-

□ Broad-spectrum cephalosporin for grade I and II injuries

-

□ Aminoglycoside added for Gram-negative coverage in grade III injuries

-

□ Penicillin or clindamycin added for severely contaminated injuries (i.e., farm injuries)

-

-

Tetanus toxoid

-

Wound coverage with sterile dressing to prevent further contamination

-

Splinting of injured extremity to prevent further soft tissue damage

Surgical Indications and Contraindications

-

An open fracture is a surgical emergency.

However, life-threatening injuries must be evaluated and treated first.

Operating room treatment is then considered. -

Wound margins are extended for visualization and débridement of all contaminated tissue.

-

Contaminated and necrotic tissue is thoroughly débrided and irrigated, devitalized bone is removed and the wound is left open.

-

Routine use of perioperative cultures has

not been shown to be effective and is not recommended. Primary closure

of open wounds and retention of devascularized fragments in children

are controversial and data limited, therefore a conservative course is

recommended. -

Stable fractures with minor soft tissue

injury may be splinted or casted. However, unstable fractures or those

with significant soft tissue injury benefit from operative

stabilization. -

Because children are smaller and

generally heal quickly, implants do not necessarily need to meet the

biomechanical requirements of implants used in adults. Kirschner-wires,

flexible intramedullary nails, external fixation, and small plates and

screws are commonly used. -

Delayed primary closure, split thickness

skin grafting, or free tissue transfers are performed once a stable,

clean wound is obtained. Despite the increased technical challenge of

smaller vessels in pediatric free tissue transfer, the general health

status and lack of premorbid conditions make success more likely and

excellent results have been reported.

Results and Outcome

-

While good outcomes of lower grade

injuries in most published studies dealing with open fractures in

children have been reported, the risk of complications is increased

with higher fracture grades. -

Delayed union, nonunion, infection, and compartment syndrome are all found with increasing frequency in higher grade injuries.

-

□ Delayed union is reported in 5% to 33%

of all open tibia fractures in children and nonunion rates of 0% to 16%

have been documented. -

□ Bone healing complications in open forearm fractures in children have been reported in 22% of patients.

-

□ The effect of age on delayed union and

nonunion is controversial, with some studies finding an increased rate

of delayed union and nonunion in older children.

-

-

Lawnmower injuries in children may be

devastating. Shredding injuries are associated with a high risk of

amputation and poor long-term results. -

Open physeal injuries frequently occur as a result of direct trauma and growth arrest is more likely.

Complications

-

Compartment syndrome

-

Delayed union

-

Nonunion

-

Infection

-

Limb length discrepancy

-

Angular deformity

-

Motion loss

Postoperative Management

-

The less rigid implants used and the usual activity levels of children dictate a period of immobilization and protection.P.179

-

□ Children are unlikely to develop

permanent stiffness, and immobilization to allow fracture healing

rarely compromises final range of motion. -

□ Implants are removed after fractures heal and before bony overgrowth occurs.

-

-

While physical therapy may be required in

older children or children with severe soft tissue injuries, it is

often unnecessary in young children or children with lesser degrees of

injury. -

▪ The potential for overgrowth and limb

length discrepancy in long bone fractures and growth arrest and

deformity in physeal injuries requires long-term follow-up and regular

radiographic review in children.

SUGGESTED READING

Buckley

SL, Smith G, Sponseller PD, et al. Severe type III open fractures of

the tibia in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:627-634.

SL, Smith G, Sponseller PD, et al. Severe type III open fractures of

the tibia in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:627-634.

Buckley SL, Smith G, Sponseller PD, et al. Open fractures of the tibia in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1990;72A:1462-1469.

Cramer

KE, Limbird TJ, Green NE. Open fractures of the diaphysis of the lower

extremity in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1992;74:218-232.

KE, Limbird TJ, Green NE. Open fractures of the diaphysis of the lower

extremity in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1992;74:218-232.

Cullen MC, Roy DR, Crawford AH, et al. Open fracture of the tibia in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;78:1039-1047.

Dormans JP, Assoni M, Davidson RS, et al. Major lower extremity lawnmower injuries in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;15:78-82.

Greenbaum G, Zionts LE, Ebramzadeh R. Open fractures of the forearm in children. J Orthop Trauma 2001;15:111-118.

Haasbeek JF, Cole WG. Open fractures of the arm in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77:576-581.

Hope PG, Cole WG. Open fractures of the tibia in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74:546-553.

Kreder

HJ, Armstrong P. The significance of peri-operative cultures in open

pediatric lower extremity fractures. Clin Orthop 1994;302:206-212.

HJ, Armstrong P. The significance of peri-operative cultures in open

pediatric lower extremity fractures. Clin Orthop 1994;302:206-212.

Lewallen RP, Peterson HA. Nonunion of long bone fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1985;5:135-142.

Shapiro J, Akbarnia BA, Hanel DP. Free tissue transfer in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:590-595.