Granulomatous Infection

Editors: Tornetta, Paul; Einhorn, Thomas A.; Damron, Timothy A.

Title: Oncology and Basic Science, 7th Edition

Copyright ©2008 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Section

IV – Basic Science > 27 – Infectious Disorders of Bone and Joint

> 27.2 – Granulomatous Infection

IV – Basic Science > 27 – Infectious Disorders of Bone and Joint

> 27.2 – Granulomatous Infection

27.2

Granulomatous Infection

Granuloma is defined as a microscopic-sized aggregation

of histiocytes and hypertrophied fibroblasts termed epithelioid cells,

centrally located and rimmed by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate of

lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 27.2-1). The

entire focus can be surrounded by a ring of fibrosis. Multinucleated

giant cells, with a characteristic positioning of the nuclei at the

periphery of the cell (foreign body or Langhans giant cells), are

frequently present (Table 27.2-1). Over time

the granuloma may be replaced by scarring and even calcification. In

tuberculosis, the central area may undergo caseous (cheese-like)

necrosis.

of histiocytes and hypertrophied fibroblasts termed epithelioid cells,

centrally located and rimmed by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate of

lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 27.2-1). The

entire focus can be surrounded by a ring of fibrosis. Multinucleated

giant cells, with a characteristic positioning of the nuclei at the

periphery of the cell (foreign body or Langhans giant cells), are

frequently present (Table 27.2-1). Over time

the granuloma may be replaced by scarring and even calcification. In

tuberculosis, the central area may undergo caseous (cheese-like)

necrosis.

-

Conditions associated with granulomatous histology (see Fig. 27.2-1) include:

-

Infection by mycobacteria, fungi, or parasites

-

Foreign materials

-

Eosinophilic granuloma

-

SarcoidosisThe response in bone is indolent, with slowly enlarging

lytic defects in bone with smooth walls accommodating confluent,

usually caseating granulomas.

-

-

Eosinophilic granuloma (Langerhans cell

histiocytosis or Langerhans cell granulomatosis) only infrequently has

clear-cut granulomatous histology (see Table 27.2-1).

This disorder can progress with rapid local osteolysis (unique among

granulomatous bone processes, which are usually indolent).

Mycobacterial Osteomyelitis

-

Tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in detail as the prototype disorder in this section.

Pathophysiology

General

-

Tubercle bacillus induces an acute

inflammatory response on entry into host tissue that usually controls

the infection, walling it off to form a primary complex; if infecting

dose overwhelms the response, the infection persists and spreads;

during the early stages, bacilli may move into the circulation and

metastasize to central nervous system, bones, or liver. -

PMNs, on ingesting the bacilli, may necrose and become engulfed by macrophages and mononuclear cells.

-

Macrophages adopt epithelioid morphology

on accepting the lipids of the bacilli, or may aggregate to form

Langhans giant cells, whose task is to digest and remove the bacilli;

these cells may also be overcome by the bacillus, also necrosing and

inducing further phagocytic activity. Necrosis of epithelioid and

Langhans cells becomes confluent (caseating). -

After 1 week, lymphocytes form a ring around the periphery of the lesion, forming a 1- to 2-mm nodule known as the tubercle.

-

During the second week caseation starts to occur, induced by the protein fraction of the tubercle bacilli.

-

Over time, the PMN response is replaced

by chronic inflammatory round cell infiltration accompanied by a

fibroblastic proliferation that is variable in degree around the

tubercle (chronic inflammatory focus). -

This immune response usually will control

the infection, in essence walling it off, where it can lie dormant for

a lifetime, potentially becoming active as old age and impaired immune

response occur.P.509P.510 Figure 27.2-1 Granuloma (TB).

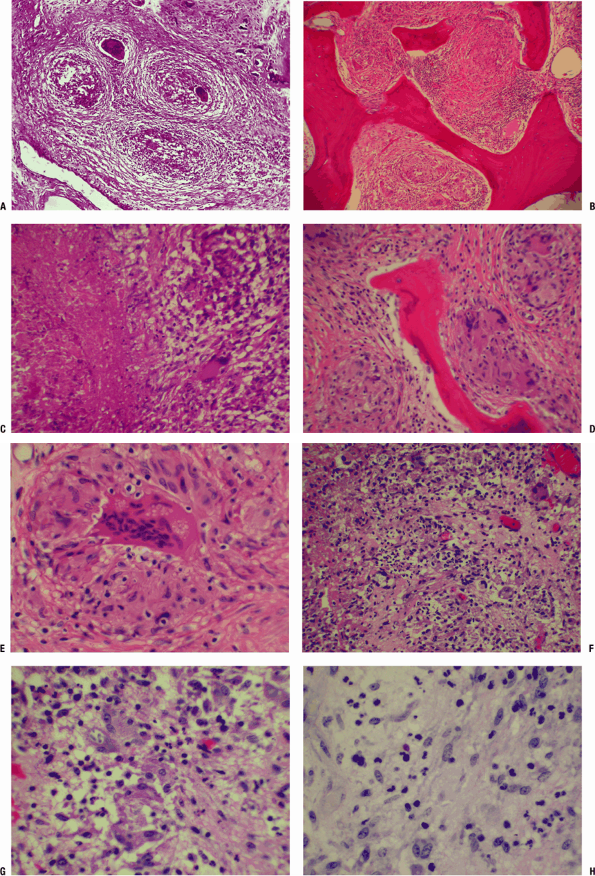

Figure 27.2-1 Granuloma (TB).

(A) Granuloma formation is present. At this power, cellular detail is

not visible, but there are four granulomas present, each within a ring

of fibrosis. The center of the granuloma may manifest caseous necrosis;

these granulomas are in the earliest stages of central necrosis. There

are multinucleated giant cells of the Langhans or foreign body type

frequently found in the granuloma. (B,C) Caseating granuloma (TB). (B) Here, granulomas are seen replacing normal marrow elements within bone. (C)

Necrotic material is seen on the left, and the intermediate margin

shows epithelioid cells centrally, with inflammatory cells

(lymphocytes, plasma cells on the right, and a Langhans giant cell).

Langhans cells have peripherally placed nuclei and are the cells to

study carefully for the presence of acid-fast bacilli or fungi. (D,E) Granulomatous osteomyelitis (foreign body).

Strictly speaking, a granuloma is a microscopic structure formed by two

or more histiocytes or macrophages. They tend to have a nodular or

circumscribed appearance and can be non-necrotizing or necrotizing. (D)

In this photomicrograph, well-formed non-necrotizing (noncaseating)

granulomas of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells are evident,

surrounded by fibrous connective tissue. Granulomas on hematoxylin and

eosin stain are not specific, and their evaluation requires an

evaluation of special stains and examination under polarized light

(birefringent foreign particles are highlighted in this manner). (E) Higher-power view of D

brings out the details of a single foreign body granuloma. Note the

multinucleated giant cell and the surrounding plump mononuclear cells

(histiocytes/macrophages). The vacuolated cytoplasm of the

multinucleated giant cells underscores the brisk metabolic activity of

these phagocytic cells. (F–H) Granulomatous (fungal, mycotic) osteomyelitis secondary to Cryptococcus infection. (F)

This field shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a few small

discrete noncaseating granulomas composed of histiocytes and a few

giant cells. Note the pale blue spherical structures within the

cytoplasm of some of the histiocytes. Special stains (e.g., GMS and PAS

stains) are useful for identification of the organism. (G) Higher-power view of F

brings out the details of the histiocytes and multinucleated giant

cells. A few gray-blue intracellular spherical bodies suspicious for

fungi are noted. (H) Same view as in G

with PAS stain (one fungal organism positive), which brings out a

dark-pink spherical structure that is morphologically consistent with

the yeast form of Cryptococcus species (this species has a capsule rich in mucin, which is readily stained by PAS). -

Musculoskeletal lesions form by metastasis from 3 months to 3 years after the primary infection.

Spine

-

Children: Spine involvement begins in the vertebral body, usually anteriorly, then extends to adjacent disc and vertebral body.

-

Adults: Onset is beneath the periosteum

under the anterior longitudinal ligament and may spread up and down the

spine, bypassing some vertebrae to lodge at more than one level; disc

space narrowing, vertebral body destruction, collapse with kyphosis,

and eventual fusion may occur after 1 to 2 years.

Extraspinal

-

Unlike bacteria, TB does not produce

proteolytic enzymes that aggressively destroy cartilage, affording more

time to make the diagnosis before the joint is destroyed in tuberculous

arthritis. -

Bacillus lodges in synovium and proliferates, opposed by the immune process in sequence as outlined above.

-

The inflamed synovium enlarges to fill all recesses

P.511

of the joint, spreading over the cartilage from the periphery as a

pannus, mechanically eliminating nutrition of the cartilage from the

surface.Table 27.2-1 Langhans Versus Langerhans CellsLanghans Cells Langerhans Cells Appearance Giant cells with nuclei distributed around the periphery Histiocytes with typical coffee-bean cleaved nuclei (NOT giant cells) Associated conditions Tuberculosis, foreign body granulomas Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Langerhans cell granulomatosis or eosinophilic granuloma (older terminology) -

Central joint space is preserved for months.

-

-

Cold abscess

-

A marked exudative reaction consists of serum, PMNs, caseous material, bone debris, and tubercle bacilli.

-

This collection migrates under the

influence of gravity and may present along the spine and pelvis, in the

groins, or about involved joints. -

It may present through the skin as a

sinus or ulcer, which may then become secondarily infected, obscuring

the diagnostic picture.

-

-

Regional osteopenia

-

The inflammatory process induces an

active hyperemia with osteoclastic deletion of bone, resulting in

marked regional osteopenia.

-

-

Kissing sequestrate

-

The inflammatory synovial mass invades weakened subchondral bone from the periphery.

-

Rarely, sequestration of the opposing

joint surfaces can occur as a result of this bone destruction, leading

to the radiographic picture of “kissing sequestrate.”

-

Etiology

-

Causative organisms include Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), Mycobacterium leprae, and environmental mycobacteria.

-

Organisms grow on enriched medium slowly so that colonies appear at 2 to 4 weeks.

-

Acid-fast stain may reveal classic “red snappers.”

-

Epidemiology

-

One third of global population is infected with TB; most frequent cause of death and disability worldwide.

-

U.S. statistics

-

10 million are infected; 90% of new activated cases come from this pool.

-

In non-Hispanic whites, median age at diagnosis is 61; among minority groups it is 39.

-

Americans >65 represent 6.5% of population but account for 26% of reported cases.

-

20% of new cases of TB have extrapulmonary disease.

-

33% of patients with TB and HIV have extrapulmonary disease.

-

1% to 3% of patients with TB develop musculoskeletal manifestations.

-

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

-

Classic: Patient becomes insidiously ill and develops chronic local musculoskeletal pain, fever, and weight loss.

-

Initial presentation may include:

-

Cold abscess: juxta-articular or paraspinal soft tissue mass without inflammation

-

Spinal involvement: may be truncal

rigidity, muscle spasm, and neurological signs and deficit; spinal

deformity (gibbus) is a late finding -

TB arthritis: more common than TB osteomyelitis

-

Dactylitis: Small joints of the hands and

feet are infrequently involved except in infancy, when digits may be

involved with swelling. -

Osseous disease: occurs by metastatic

spread from an initial focus, usually the lungs, with involvement most

often of spine (lower thoracic most frequent, with multiple vertebral

bodies in 50% of cases), followed by pelvis in 12%, hip and femur 10%,

knee and tibia 10%, hand, and any other joint

-

-

Important clinical points

-

Diagnosis can be difficult in the elderly, whose presentation may initially be only nonspecific constitutional symptoms.

-

If you suspect musculoskeletal TB, check the lungs, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

-

Radiologic Features

-

No pathognomonic features

-

Joints

-

Osteopenia and soft tissue swelling with

minimal periosteal reaction early, then marginal deletion of

subchondral bone on both sides of the joint with late loss of central

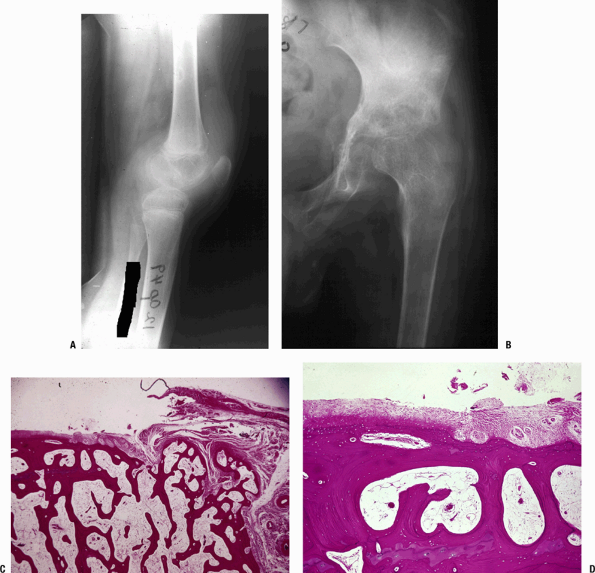

joint space (Fig. 27.2-2)P.512![]() Figure 27.2-2 (A)

Figure 27.2-2 (A)

TB of the knee. When TB first lodges in the synovium of a joint, it

creates many tubercles (usually small, without caseation) and induces

marked synovial proliferation. The suprapatellar pouch in this knee is

filled with inflamed synovium with histology as in Figure 27.2-1. There is significant osteopenia. (B–D) TB of the hip. (B)

Once the infection is established, the inflamed synovium invades the

joint space from the margins, growing as a pannus as in rheumatoid

arthritis, destroying the underlying cartilage by interfering with the

diffusion of nutrients to the cartilage. The joint surface is usually

preserved centrally until the process becomes much more advanced.

Synovial pathology involves both sides of the joint. TB must be in the

differential diagnosis for any periarticular disorder involving more

than one bone around a joint area or marginal erosions. (C) Photomicrograph of the edge of a joint showing the pannus growing from the right onto the underlying articular cartilage. (D) This higher-power view shows complete destruction of the cartilage by the pannus. -

Subchondral cysts

-

Enlargement of epiphysis

-

Subchondral erosions may cross epiphysis in one third of children affected.

P.513 -

-

Spine

-

Rarefaction of vertebral endplates

-

Increasing loss of disc height

-

Focal bony destruction with disc involved and late vertebral body collapse (Fig. 27.2-3)

-

Paravertebral soft tissue mass often present

-

Needle biopsy in HIV/TB patients must rule out other diseases such as Kaposi sarcoma.

-

Mycotic Osteomyelitis

-

Occurs mostly in immunocompromised

patients or as opportunistic infections in individuals exposed to the

specific contaminated environment (workers) -

Fungal infection mimics TB, so always culture for fungi if granulomatous pathology is found (see Fig. 27.2-1).

-

Radiographic differential includes myeloma and metastasis (due to frequent multifocality).

-

Relevant features of the fungal infections of the musculoskeletal system are outlined in Table 27.2-2.

Sarcoidosis

-

A systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown cause; no known organism

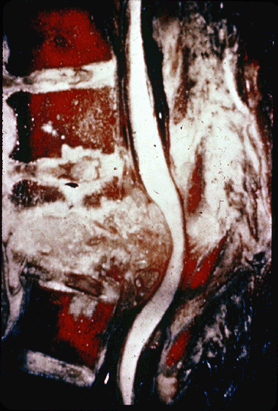

Figure 27.2-3

Figure 27.2-3

Gross specimen of TB of the spine. There is marked destruction of the

bony architecture, with extension of the granulomatous process

extending posterior to compress the cord. This degree of destruction

can produce spinal deformity and paraplegia. -

Differential diagnosis in any clinical situation manifesting granulomatous histology

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

-

Typical patient is an adult, more commonly African-American, age 20 to 40 years, with fever, fatigue, malaise, and weight loss.

-

Affects lungs (90%), lymph nodes, skin, skeleton

-

Skeletal distribution: hand (“sausage fingers”), wrist, foot, skull, vertebral bodies, long bones, synovium

-

Typical musculoskeletal presentation: swollen, mildly painful fingers

-

Radiologic Features

-

No large destructive lesions as seen more commonly with TB

-

Mixed lysis and sclerosis is typical.

-

Hands/feet: punched-out cortical lesions,

with trabecular resorption (honeycomb lytic pattern) and linear

end-osteal sclerosis (acro-osteolysis; Fig. 27.2-4)

Laboratory Findings

-

Elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) derived from epithelioid cells

-

Hypercalcemia arising from overproduction of 1-25-(OH)-D3, driven by activated pulmonary macrophages

-

Cultures negative

Pathologic Findings

-

Mimics TB but without caseation (see Fig. 27.2-4)

-

Giant cells show nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions.

-

Asteroid body: a central core of degenerating organelles encompassed by rays of collagen

-

Schaumann bodies: large, concentrically laminated concretions of a protein matrix impregnated with calcium and iron salts

-

Treatment

-

Symptoms are usually self-limited. If severe, prolonged treatment with corticosteroids may be attempted.

-

Immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide can be used.

-

Rarely, some individuals with irreversible organ failure require organ transplantation.

Rare Forms of Osteomyelitis

These conditions, whose relevant information is outlined in Table 27.2-3, include:

-

Brucellosis

-

Cat-scratch disease

-

Microangiopathic osteomyelitis

-

Syphilis

-

Lyme disease

-

-

Fibrosing osteomyelitis (fibrocystic)

-

Ecchinococcosis

-

P.514

P.515

|

Table 27.2-2 Fungal Forms of Osteomyelitis

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.516

|

|

Figure 27.2-4 Boeck’s sarcoid. (A) Radiograph shows a small lytic lesion with sclerotic borders in the proximal phalanx of the great toe. (B) A small tubercle in sarcoid, with each of the cellular elements of a granuloma demonstrated.

|

P.517

P.518

P.519

P.520

|

Table 27.2-3 Rare Forms of Osteomyelitis

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P.521

Suggested Reading

Marchevsky

AM, Damsker B, Green S, et al. The clinicopathological spectrum of

non-tuberculous mycobacterial osteoarticular infections. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1985;67(6):925–929.

AM, Damsker B, Green S, et al. The clinicopathological spectrum of

non-tuberculous mycobacterial osteoarticular infections. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1985;67(6):925–929.

Rasool MN. Osseous manifestations of tuberculosis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21(6):749–755.

Sponseller PD, Malech HL, McCarthy EF, Jr, et al. Skeletal involvement in children who have chronic granulomatous disease. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1991;73(1):37–51.

Tuli SM. General principles of osteoarticular tuberculosis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2002;398:11–19.

Zlitni M, Ezzaouia K, Lebib H, et al. Hydatid cyst of bone: diagnosis and treatment. World J Surg 2001;25(1):75–82.