Continuous Thoracic Paravertebral Block

Continuous thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB) is performed most easily

with the patient in the sitting position with feet dangling over the

side of the bed. It is also possible to perform the block in the

lateral or prone position.

The use of a Tuohy needle is preferred because its blunt, rounded tip

provides a distinct “pop” on penetrating the costotransverse ligament

and may diminish the chance of perforating parietal pleura. For

continuous TPVB use an 18-gauge Tuohy needle with graduated markings

and 20-gauge polyamide closed-tip, multiport catheter. More flexible

epidural catheters are not recommended as they will be difficult to

insert.

An initial injection through the needle of 5 mL of ropivacaine 0.5% to

help distend the paravertebral space and facilitate catheter insertion.

This is followed by the injection of an additional 10 mL through the

catheter. After the surgery, the catheter is infused with 0.2%

ropivacaine at a rate of 7 to 10 mL/hr.

The thoracic paravertebral space is a triangular space whose boundaries

include anteriorly the parietal pleura, posteriorly the superior

costotransverse ligament, and medially the vertebral body,

intervertebral disc, and intervertebral neural foramen. The apex of the

triangle laterally is continuous with the intercostal space. The space

is bisected by the very thin endothoracic fascia which creates two

“compartments.” The anterior compartment contains the sympathetic

chain, and the posterior compartment contains the intercostal nerve,

dorsal ramus, intercostal blood vessels, and

rami

communicantes. Spinal nerves in the paravertebral space are relatively

devoid of fascial covering making them uniquely and exceptionally

sensitive to local anesthetic blockade. The important anatomic surface

landmark for TPVB is the relevant spinous process or processes for the

desired dermatomes to be blocked. Note that the steep angulation of

thoracic spinous processes brings them opposite the transverse

processes of the adjacent more caudad vertebra.

|

Table 31-1. Indications

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

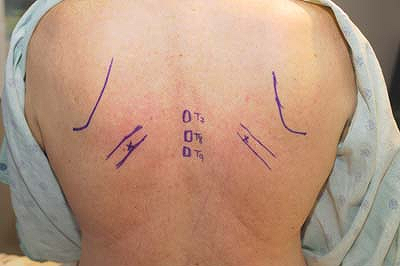

The relevant spinous processes are identified and marked on the skin

and a point 2.5 cm lateral to the spinous process is also marked (Fig. 31-1).

Disinfectant is applied in standard fashion and local anesthetic (1%

lidocaine) injected at each injection point using a 1.5-cm 25-gauge

needle. The Tuohy needle is advanced onto the transverse process and

the depth from skin to paravertebral space marked by placing the index

or third fingers on the needle shaft 1 cm from the skin (Figs. 31-2, 31-3).

This will now serve as both a depth gauge and a guard against excessive

insertion of the needle. The needle is then walked caudally off the

inferior border of the transverse process and inserted to a depth 1 cm

deeper than the transverse process—that is, to the depth allowed by

prior placement of the index fingers on the needle shaft. Typically at

this point one feels a confirmatory “pop” upon penetration of the

costotransverse ligament. A drop of fluid is placed in the needle hub

and the patient is asked to inspire deeply (Fig. 31-4).

Correct placement is denoted by lack of movement of the fluid bubble. A

drawing inward of the fluid indicates intrapleural needle placement, in

which case the needle should be immediately withdrawn. After correct

needle placement is thus confirmed, 5 mL of local anesthetic is

injected through the needle. It is helpful to have an assistant inject

through an extension tube as this helps avoid significant movement of

the needle. Following the injection the extension tube is disconnected

and the catheter inserted a depth of 3 to 5 cm beyond the tip of the

needle (Fig. 31-5). The catheter is affixed in standard fashion using adhesive strips and transparent dressing (Fig. 31-6).

|

|

Figure 31-1. The skin is marked at 2.5 cm lateral to the spinous process.

|

|

|

Figure 31-2.

The finger placement on the needle shaft will serve as both a depth gauge and a guard against excessive insertion of the needle. |

-

Depth of the adult paravertebral space

from the skin ranges between 3 and 7 cm except for the morbidly obese.

Surprisingly, depth correlates only weakly with height, weight, and BMI. -

Limit volume of injectate through the

needle—the higher pressures when injecting through the needle may force

the local anesthetic through the intervertebral foramen into the

epidural space. -

Any significant resistance to injection through the needle indicates improper needle placement.

-

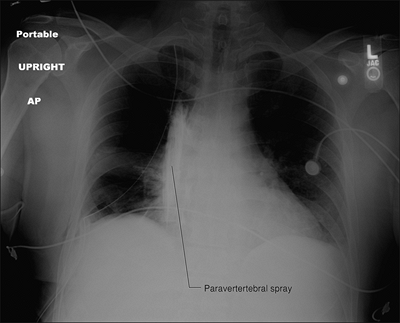

When using paravertebral catheters there

is no need to perform injections at multiple levels; clinically the

block is extended over more dermatomes by simply increasing the local

anesthetic infusion rate (Fig. 31-7). -

Abdominal and retroperitoneal surgery (e.g., nephrectomy) typically require placement of bilateral paravertebral catheters.

-

The catheter is positioned with the

understanding that the spray is more caudal (3 to 4 dermatomes) than

cephalad (1 or 2 dermatomes). Figure 31-3.

Figure 31-3.

The Tuohy needle is advanced onto the transverse process and the depth

from skin to paravertebral space marked by placing the index or third

fingers on the needle shaft 1 cm from the skin.![]() Figure 31-4. A drop of fluid is placed in the needle hub and the patient is asked to inspire deeply.P.262

Figure 31-4. A drop of fluid is placed in the needle hub and the patient is asked to inspire deeply.P.262 Figure 31-5.

Figure 31-5.

Following injection of 5 mL of local anesthetic, the extension tube is

disconnected and a catheter inserted to a depth of 3 to 5 cm beyond the

tip of the needle.![]() Figure 31-6. Catheter fixation technique.

Figure 31-6. Catheter fixation technique. -

Verification of catheter placement with x-ray although interesting, is not necessary.

-

Inadvertent placement of the catheter

interpleurally is acceptable although not desirable and will provide

analgesia as an interpleural block instead. In the case of thoracic

surgery, an interpleural block will not provide acceptable analgesia,

but the surgeon will clearly see the catheter in the chest and alert

you to the need for repositioning it. Figure 31-7.

Figure 31-7.

Injection of 10 mL omnipaque contrast via PVB catheter following

thoracotomy demonstrates extensive caudo–cephalad paravertebral spread. -

Routine postoperative x-ray to rule out

pneumothorax may be comforting but is not absolutely necessary.

Nevertheless, one should always have an index of suspicion for this

uncommon complication. -

In the case of trauma and spine injury,

in the absence of “spine clearance,” or in the anticoagulated patient

it would be preferable to use an alternative technique to continuous

thoracic paravertebral blocks such as percutaneous continuous

intercostal blockade or a continuous interpleural block. -

Avoid medial redirection of the needle as this may predispose to inadvertent neuraxial blockade.

-

If one encounters a “wall of bone” in

walking the needle caudad–cephalad in the sagittal plane then the

needle is probably too medial encountering the lamina and

superior-inferior articular processes. Redirect slightly laterally. -

Use graduated needles as this helps avoid excessive needle penetration. In addition use index fingers as depth gauge/guard.

-

Use a 22-gauge Tuohy single-shot needle

to define location and depth of the transverse process prior to use of

the larger catheter insertion needle, especially in morbidly obese

patients. -

Walk caudally, not cephalad, off the

transverse process as the distance between the costotransverse ligament

and the pleura is greater here. The rib, which is deep to the

transverse process, usually rises more cephalad. Thus walking the

needle cephalad will mean that the needle is walking off the rib, not

the transverse process. -

Tunneling of the catheter is not necessary if proper taping technique is used.

-

Verify needle position using the hanging

droplet technique. Deep inspiration will pull the droplet in if the

needle is interpleural. The droplet will bulge outward if the needle is

in the paraspinal muscles. -

The catheter exits the needle at

approximately an angle of 30°. If one encounters difficulty passing the

catheter even after expanding the paravertebral space by injecting

local anesthetic or saline one may try, with the Tuohy needle opening

directed caudad, applying a slight cephalad torque to allow the

catheter greater ease of deflecting off the pleura. One may also try

rotating the needle to pass the catheter laterally. If this fails, try

reinserting the needle at a steeper angle. -

Continue to monitor the patient after placement of the block. Neuraxial block onset and its sequelae may be delayed.

-

On initial injection of local anesthetic

into the paravertebral space patients will frequently complain of a

momentary “pinch” or “cramp” in their side. This paresthesia is a good

indication of proper placement. -

As with other continuous peripheral nerve blocks, patients may be discharged home with disposable infusion pumps.

-

Up to 8% of patients demonstrate a vagal

response during performance of the block. Therefore, a prepared syringe

of an anticholinergic drug (e.g., glycopyrrolate) and a syringe with a

pressor agent (e.g., ephedrine) should be immediately at hand.

RG, Myles PS, Graham JM. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and

side-effects of paravertebral vs. epidural blockade for thoracotomy—a

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth 2006;96:418–426.

MK, Critchley LA, Ho AM, et al. Continuous thoracic paravertebral

infusion of bupivacaine for pain management in patients with multiple

fractured ribs. Chest 2003;123:424–431.

MZ, Ziade MF, Lönnqvist PA. General anaesthesia combined with bilateral

paravertebral blockade (T5-6) vs. general anaesthesia for laparoscopic

cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Eur J Anaesth 2004;20:489–495.

G, Pither CE, Justins DM. Paravertebral somatic nerve block: a

clinical, radiographic, and computed tomographic study in chronic pain

patients. Anesth Analg 1989;68:32–39.

J, Cheema SP, Hawkins J, Sabanathan S. Thoracic paravertebral space

location. A new method using pressure measurement. Anaesthesia 1996;51:137–139.

J, Sabanathan A, Jones J, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison

of preoperative and continuous balanced epidural or paravertebral

bupivacaine on post-thoracotomy pain, pulmonary function and stress

response. Br J Anaesth 1999;83:387–392.

A, Stieger DS, Theurillat C, Curotolo M. Single-injection thoracic

paravertebral block for postoperative pain treatment after

thoracoscopic surgery. Br J Anaesth 2005;95:816–821.

For blockade above T7, the patient is best positioned sitting with the

arms dangling between the knees to bring the scapulae apart, thereby

allowing better access to the upper thoracic ribs.

The indications are similar to those for the classic paravertebral

block. These include all surgical procedures of the chest and abdomen

including thoracic surgery—both open and video assisted, conventional

and minimally invasive cardiac surgery, breast surgery, plastic

reconstructive or cosmetic surgery, and pectus repair. Urologic

surgical indications include renal, adrenal, ureteral, bladder, and

prostatic surgery. General surgical indications include both open and

laparoscopic surgeries such as bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy,

herniorrhaphy, pancreatic and liver surgery, and bowel surgery.

Gynecologic surgical indications include hysterectomy, myomectomy,

fallopian tube, and ovarian surgery. Nonsurgical indications include

liver capsule pain, rib fractures, acute postherpetic neuralgia, and

chronic pain management for both benign and malignant neuralgias. The

surgical site will of course dictate whether unilateral or bilateral

neural blockade is needed. For retroperitoneal and abdominal surgeries,

typically bilateral blockade is necessary. This technique may be

advantageous in situations where the classic technique would be

contraindicated (e.g., coagulopathies, thrombocytopenia,

anticoagulation therapies, spinal trauma, or previous spinal surgery).

An 18-gauge, 2-inch Tuohy needle and 20-gauge closed-end, multiorifice,

stiff plastic catheter. For obese patients a 4-inch Tuohy needle may be

needed.

The intercostal nerve lies with the artery and vein under the rib in

the subcostal groove between the internal and innermost intercostal

muscles. The puncture site is at the angle of the rib about 8 cm

lateral to the midline. The inferior border of the scapulae is marked

bilaterally. The line connecting the two inferior angles usually runs

through the vertebral body of T7. The desired rib is then delineated.

The lower third of the rib 8 cm from the midline is the entry site.

The skin is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. Thereafter the

skin and subcutaneous tissue under the entry site is anesthetized with

1% lidocaine until the rib is contacted and the periosteum is

generously anesthetized. The Tuohy needle is then advanced directly

inward to contact the lower third of the rib. The needle is then angled

laterally at 45° to 60° with the bevel facing the spinous process and

is gently walked off the inferior border of the rib while maintaining

this orientation. Once under the rib the needle is advanced 5 to 6 mm

to lie within the subcostal groove. After negative aspiration of heme

or air and a negative fluid drop aspiration test, 5 mL of local

anesthetic is injected followed by passage of the catheter toward the

midline. The catheter is left at the combined distance of 8 cm plus the

depth of the needle such that the tip is left at the ipsilateral

paravertebral space. After securing the catheter, bolus another 10 mL

of the local anesthetic to establish adequate spread. Postoperative

infusions are typically run at 10 to 12 mL/hr (Figs. 31-8, 31-9 and 31-10).

|

|

Figure 31-8. Anatomic landmarks.

|

|

|

Figure 31-9. Needle orientation.

|

-

For blockade below T7, the patient can be positioned either sitting or laterally.

-

0.5 to 1 mg of midazolam with 25 to 50 µg

of fentanyl may improve patient comfort, but in most patients, sedation

is not necessary. -

The shorter needle is used to allow more

precise control over the needle, as the usual depth to the subcostal

groove is 2 to 4 cm. -

To facilitate walking under the rib

without having to drop the angle of the needle (and by so doing miss

the neurovascular bundle tucked up along the rib in the subcostal

groove), the skin should be lifted cephalad somewhat before entering

the skin thereby allowing it to easily come with the needle as it is

walked off instead of impeding the movement. -

To confirm extrapleural placement after

advancing the needle into the subcostal groove and before threading the

catheter, the stylet should be removed and a drop of fluid placed

within the needle and the patient is asked to inhale. If the fluid is

entrained the needle should be pulled back 1 to 2 mm and the test

repeated. -

Upon passing the catheter to the

paravertebral space there should be a small amount of resistance. If

there is no resistance, the catheter may actually be interpleural. See Chapter 30 on interpleural catheters for their management. Figure 31-10. Threading the catheter.

Figure 31-10. Threading the catheter. -

0.5% ropivacaine is typically used for

the initial bolus at placement and 0.2% ropivacaine at 10 mL/hr

postoperative infusion. The nursing staff also has orders for 5 to 6 mL

boluses available q1 hr for breakthrough pain.

DA, Bruce Ben-David B, Chelly JE, Greensmith JE. Continuous

percutaneous intercostal block: an alternative approach to continuous

paravertebral blockade. Anesth Analg 2007; in press.

J, Sabanathan S, Jones J, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison

of preoperative and continuous balanced epidural or paravertebral

bupivacaine on post-thoracotomy pain, pulmonary function and stress

responses. Br J Anaesth 1999;83:387–392.