Dermatologic and Infectious Diseases

are very common in athletes. The close quarters of locker rooms, shared

equipment, and skin-to-skin contact with other athletes aids in

transmission of these infections. In addition, warm, moist skin is an

ideal environment for many types of skin infections to flourish. It is

essential for sports medicine physicians to be able to recognize the

signs and symptoms of common infections. It is also important to

understand what conditions may call for temporary disqualification of

an athlete from competition.

most common infectious skin rashes and respiratory infections

encountered. We will discuss the course and treatment of these

illnesses. Finally, we will discuss special considerations in athletes.

types: herpes simplex 1 (HSV1) and herpes simplex 2 (HSV2). These two

types produce identical lesions and are treated the same. Therefore, it

is not essential to make the distinction between the two types at

diagnosis. Generally, HSV1 produces oral lesions such as the common

“cold sore” and

is

more common in infections obtained from athletic events. HSV2 tends to

be more common in genital infections. Herpes is spread by direct

contact with herpes lesions or by contact with fluid that contains the

virus, such as saliva or cervical secretions. The herpes virus does not

live long outside of the body, so skin-to-surface spread is uncommon.

After exposure, there is a variable incubation period of 2 to 14 days

before lesions first appear. The first time someone is infected with

herpes is considered the primary infection. The primary infection

differs from the secondary infection because the lesions generally last

longer and are preceded by prodromal symptoms—such as body aches,

fever, generalized fatigue, headaches, and tender lymph nodes—all of

which may occur a few days before the appearance of herpes lesions.

Typically, the lesions of herpes in a primary infection last 2 to 6

weeks. After the lesions heal, the virus then enters peripheral nerves

at the site of inoculation and ascends to the dorsal root ganglia,

where it remains until reactivated in a secondary infection. Herpes is

a chronic infection and can never be completely cleared from the body.

virus in the dorsal root ganglia is reactivated. The virus then travels

back through the peripheral nerve and causes lesions in the same area

as the previous primary infection. The herpes virus is opportunistic

and generally reactivates at times of stress or skin compromise. The

stress that may cause reactivation is variable. Common causes are upper

respiratory infections, fatigue, menstruation, or (in athletes) stress

as a result of an upcoming event or match. Also, any skin trauma, such

as a cut or scrape or even a sunburn in the area of prior infection,

may cause reactivation. The secondary infection is not preceded by

prodromal symptoms, and lesions generally last 10 to 14 days.

-

The appearance of skin lesions in a

herpes infection is typically preceded by some localized symptoms in

the area of the lesion, including pain, burning, and tingling—all of

which can occur 1 to 2 days before the lesion appearance. -

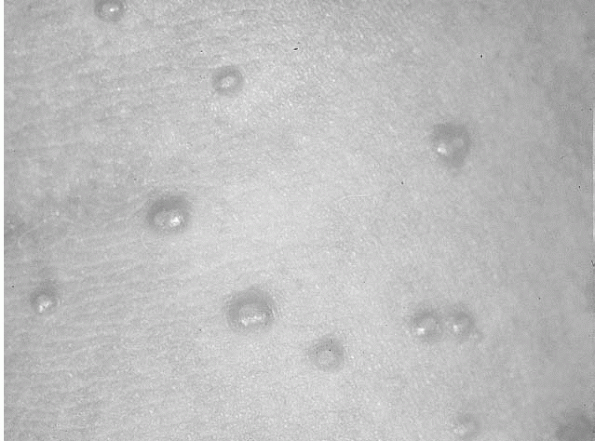

The classic description of the lesions of herpes is grouped vesicles on an erythematous base (Fig. 13-1).

-

The vesicles contain clear to serosanguineous fluid and may coalesce with adjacent vesicles to form larger lesions.

-

The virus is contained within the fluid of the vesicle, and therefore these vesicles are considered contagious.

-

The skin under the vesicles tends to be erythematous but this does not extend far beyond the lesions.

-

The vesicles rupture in a few days forming shallow erosions covered by a yellowish crust.

-

These erosions will then heal in 8 to 14 days.

-

The lesions of herpes are in the

outermost layer of the skin or the epidermis, and therefore should

generally heal without scarring.

-

-

The diagnosis of herpes can often be made

from the appearance of the lesions; but when in doubt, laboratory

evaluation can be performed.-

A herpes culture is most definitive for diagnosis.

-

Culture specimens can be taken from the fluid contained in the vesicles or swabbed from the base of a moist ulcer.

-

Culture yield is low once the lesions begin to dry.

-

Results of a herpes culture may take up to 1 week but can be available as soon as 1 to 2 days.

-

-

The other testing method is called a

Tzanck smear, which attempts to visualize multinucleated giant cells

(cells infected with the herpes virus).-

The specimen for a Tzanck smear is collected by scraping the base or edges of an ulcer with a scalpel.

-

The collected specimen is then placed on a slide, fixed, and stained.

-

The benefit to this method is that a diagnosis can be made within minutes.

-

|

|

Figure 13-1

Herpes simplex : grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

-

Herpes is a chronic, incurable disease.

-

Treatment is aimed at decreasing the time course of an outbreak, rather than curing the disease.

-

It is most effective if it is begun early in the course of an outbreak when the virus is rapidly replicating.

-

In primary infections, this is usually when the lesions first appear and are diagnosed.

-

In secondary infections, this can be

before the lesions even appear, especially if a patient has localized

symptoms before the outbreak.

-

-

At the first indication that a patient

may be developing a secondary outbreak such as localized burning or

tingling in the area of a prior outbreak, medication should be started. -

There are three antiviral medications available for the treatment of herpes: acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir.

-

In a primary infection, begin acyclovir

400 mg three times per day (TID) for 10 days, famciclovir 250 mg TID

for 10 days, or valacyclovir 1,000 mg two times per day (BID) for 10

days.-

Topical acyclovir may also be effective in primary infections and can be applied every 4 hours for 10 days.

-

-

In secondary infections, begin acyclovir

400 mg TID for 5 days, famciclovir 125 mg BID for 5 days, or

valacyclovir 500 mg BID for 3 days.-

Again, treatment is not curative but lessens the time to lesion healing.

-

-

Patients may also try a variety of drying

agents in an attempt to hasten resolution of lesions, such as alcohol,

bleach, or Betadine—none of which are medically recommended. -

A patient with frequent outbreaks of

herpes, or herpes that reoccurs predictably at times of stress, may be

prescribed prophylactic treatment.-

The prophylactic doses of the medications are acyclovir 400 mg BID, famciclovir 250 mg BID, or valacyclovir 500 mg QD.

-

-

Herpes in the athlete is typically caused by HSV1.

-

It is called herpes gladiatorum because of its frequency in wrestlers but it can occur in athletes in any contact sport.

-

It is seen most commonly in areas of contact such as the face, neck, upper trunk, and upper extremities.

-

Because of the contagiousness of this

disease and its incurable nature, athletes are disqualified from

competition in any contact sport or swimming if he or she has active

herpes lesions, even if the lesions encompass a very small area that

can be covered with a dressing or clothing.-

Athletes may return to competition only when the lesions are completely dry.

-

-

Many sports governing organizations,

including the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), require

that an athlete has had no new lesions for a 72-hour period before

competition is allowed.-

Furthermore, the NCAA also requires that

an athlete be treated with systemic antiviral medication for at least 5

days before the event and be taking the medication at the time of

competition.

-

-

As stated previously, athletes may use a variety of topical agents in an attempt to dry the lesions as quickly as possible.

-

Athletes may also use these agents in an

attempt to make the diagnosis difficult for the untrained clinician and

thereby avoid disqualification. -

If there is any question of herpes,

however, an athlete should be disqualified from contact sports until

further evaluation can be undertaken.

-

-

Because secondary herpes can occur at

times of stress, it is very common for athletes to suffer outbreaks

during times of important meets.-

If this is known to occur in a given

athlete, it may be appropriate to consider prophylactic treatment with

antiviral medications at these times.

-

epidermis of the skin. Similar to herpes, there are two types of

molluscum viruses: MCV-1 and MCV-2. Again, it is not important to make

the distinction between the two types because they cause similar

lesions and are treated the same.

contact, so lesions are typically seen in areas of exposed skin such as

the face, neck, and arms. The lesions can be spread from person to

person but can also be spread to different areas of a given individual

by autoinoculation. Although not truly considered a sexually

transmitted disease, lesions can also be present in the genital area

and therefore can be spread through sexual activity.

-

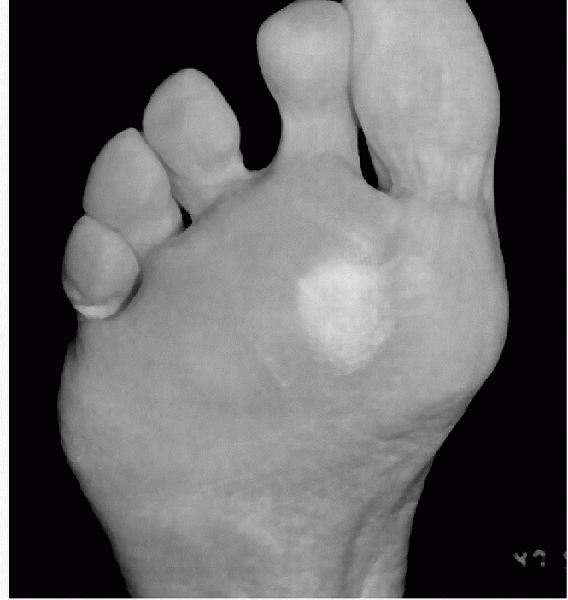

The lesions caused by molluscum contagiosum are papules 1 to 2 mm in size (Fig. 13-2).

-

They are typically white to skin-colored and are generally grouped in clusters.

-

-

One of the most characteristic traits of a molluscum contagiosum lesion is a central dimple or umbilication.

-

The umbilication is most easily seen on large lesions and is caused by a keratotic plug.

-

If this umbilication is not readily

apparent on first inspection, it can sometimes be observed after

treatment with liquid nitrogen.

-

-

Typically, the skin surrounding the

lesions appears normal; however, individual lesions may have a

surrounding erythematous halo.-

This erythema may be caused by an immune reaction to the lesion and indicates it may soon clear spontaneously.

-

-

The diagnosis of molluscum is typically made by examination.

-

If the diagnosis is unclear, however, a

Giemsa stain of the keratotic plug may reveal cells containing

inclusion bodies that are typical of molluscum. -

These intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies may also be seen on biopsy specimens.

|

|

Figure 13-2

Molluscum contagiosum. Characteristic dome-shaped papules, some with central umbilication. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

-

Molluscum lesions may undergo spontaneous resolution, but this may take up to 6 months to occur.

-

For quicker resolution, lesions can be destroyed by a variety of different methods.

-

If only a few small lesions are present, they can be removed with a curette.

-

More diffuse lesions may be treated with liquid nitrogen, electrodesiccation, or laser.

-

If the lesions are too numerous to treat

completely, treating at least some of the lesions may stimulate the

body to mount an immune response against the remaining lesions and

cause spontaneous resolution. -

It is important to remember that any of

the previously described treatments may leave a scar or area of

hypopigmentation, especially in dark-skinned individuals.-

A patient should be counseled and consented as to this possibility before treatment is attempted.

-

-

Because molluscum contagiosum is highly

treatable, and does not spread systemically, athletes with lesions may

engage in contact sports, provided the lesions can be adequately

covered.

This infection typically occurs in areas of minor superficial breaks in

the skin. The bacteria are most prevalent in skin areas with warm,

ambient temperatures, and humidity. Therefore, outbreaks are frequent

around the nose and mouth. Also, dryness and cracking of the skin

around the lips, and trauma from shaving in this area may provide an

entrance point for the bacteria. There has also been some association

of outbreaks with poor hygiene, which may lead to a prevalence of the

bacteria on the skin. Between 20% to 40% of normal adults may have

nasal colonization of S. aureus, and about 20% may have colonization of the axilla or perineum.

if left untreated it can progress to a deeper skin infection such as a

cellulitis, or may even cause a systemic bacteremia. The exotoxin

produced from S. aureus may produce

detachment of the superficial layers of the epidermis causing bullous

lesions, or in certain cases widespread desquamation called staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Exotoxins produced from either bacteria may cause scarlet fever. More

clinically concerning complications from systemic bacteremia such as

rheumatic fever and acute glomerulone-phritis, although not common,

have also been associated with untreated impetigo.

-

The classic impetigo lesion is described as an erythematous, moist-appearing macule with a honey-colored crust (Fig. 13-3).

-

This appearance, together with a common location around the lips or nose, is generally enough to make the diagnosis.

-

There may be small lesions or larger lesions formed from confluence of these smaller ones.

-

In addition to this classic appearance,

impetigo may appear bullous with small blister-like lesions or may

appear dry and scaly as it is starting to heal. -

If the diagnosis is in doubt based on

appearance, the lesions can be swabbed for Gram stain and culture to

confirm the presence of Staphylococcus or Streptococcus.

-

Although the lesions of impetigo may

resolve spontaneously, it is recommended that treatment with either

oral or topical antibiotics be initiated at the time of diagnosis

because of the risk of localized spread and systemic complications. -

Very localized infections with few lesions may be treated with topical agents.

-

Mupirocin is the topical treatment of

choice for impetigo because it is effective against even resistant

strains of both staphylococci and streptococci.-

Two-percent mupirocin ointment is applied to the lesions three or four times per day until the lesions have completely cleared.

-

-

It may also be beneficial for the

infected individual to wash with an antibacterial soap such as Betadine

or pHisoHex once per day. -

For more widespread outbreaks, oral antibiotics are recommended.

-

Penicillin is generally not adequate for treatment because of known staphylococcal resistance.

-

Erythromycin may be inadequate because of increasing staphylococcal resistance.

-

-

The preferred treatment is with an

antistaphylococcal penicillin such as cloxacillin or dicloxacillin, or

a first-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin.-

The course of treatment depends on the extent of the infection, generally from 5 to 10 days.

-

-

For those individuals who are allergic to penicillin, azithromycin, or clarithromycin may be used.

-

For those infections that do not seem to be improving with oral antibiotics, it is recommended that a culture be performed.

-

A culture can identify the bacteria involved and its specific antibiotic sensitivities and can therefore guide treatment.

-

In addition to antibiotics, infected

individuals should take measures to prevent further localized spread

(such as minimizing friction or skin trauma in the infected area),

avoid shaving the infected area, and cover lesions if possible,

especially if the lesions are moist.

|

|

Figure 13-3

Streptococcal impetigo. Erythematous macules with moist crust. (From Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.) |

-

Impetigo is commonly seen in the athlete.

-

It is typically spread from skin-to-skin contact and is frequently seen in sports such as wrestling.

-

The infection can also be spread from surface-to-skin contact.

-

Therefore, wrestling mats, locker rooms, or other common-use equipment may be the source of some infections.

-

It is essential that wrestling mats and

other common-use equipment be cleaned regularly with antiseptic

cleaners to prevent widespread outbreaks.

-

-

Because of the highly infectious nature

of impetigo and the possibility of systemic complications, infected

athletes are disqualified from contact sports until the lesions of

impetigo are completely dried and clear of any crusting, even if the

area can be adequately covered.-

In most cases, this degree of clearing occurs after about 5 days of appropriate antibiotic treatment.

-

-

The NCAA requires an athlete have had no new lesions for 48 hours before the event before competition is allowed.

-

In widespread outbreaks among teams, careful consideration as to possible sources of the infection should be explored.

-

As previously described, common-use equipment that is not adequately cleaned may be a source.

-

Another potential source is nasal colonization of team members.

-

If this is suspected, cultures can be

performed, or team members may be empirically treated with 2% mupirocin

ointment applied in the nares 3 times per day for 1 week.

-

be caused by physical irritation or, more commonly, by a bacterial

infection. Infectious folliculitis is typically caused by Staphylococcus aureus, but there is a variant of infectious folliculitis associated with the use of hot tubs called hot tub folliculitis. In hot tub folliculitis, the offending agent is often Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Similar to impetigo, the bacteria tend to proliferate and cause

infection in warm, moist environments; thus, folliculitis is commonly

seen in areas of occlusion such as under tight clothes or in skin

folds. The lesions in hot tub folliculitis frequently develop on areas

that were covered with a bathing suit. Shaving also predisposes to hair

follicle infections, because this activity can spread bacteria and

provide breaks on the skin where bacteria may enter and cause infection.

-

The typical infection of folliculitis is confined to the ostium, or superficial, portion of the hair follicle.

-

The characteristic lesions are pustules associated with hair follicles (Fig. 13-4)

-

Often, hair from the follicle can be seen extruding from the center of the pustule.

-

These infected follicles are generally grouped closely and surrounded by erythematous halos.

-

When theses pustules rupture, they appear as superficial, moist erosions, which form a crust before they heal.

-

-

Because the infection is superficial, the

lesions often heal without scarring, but may cause postinflammatory

pigment changes, particularly in dark-skinned individuals. -

Even though the infection of impetigo and folliculitis both may be caused by Staphylococcus,

in folliculitis the bacteria seem to be confined to the hair follicle,

making risk of person-to-person transmission much less with

folliculitis. -

Although the infection is typically

limited to the hair follicles, if left untreated it may progress to a

deeper dermal infection called a “furuncle.”-

A furuncle appears as a larger

erythematous nodule, which can become an abscess filled with pus and

necrotic debris. Multiple furuncles can coalesce to form a carbuncle. -

A carbuncle is characterized by a larger area of erythema and multiple skin openings draining pus.

-

When these deeper infections occur, there is greater risk of systemic bacteremia.

-

-

Pustules can be unroofed with a scalpel

or needle and cultured, which can aid in guiding treatment. This is

especially recommended in cases that do not respond to common

antibiotic treatment.

|

|

Figure 13-4

Folliculitis. Pustules associated with hair follicles. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

-

Treatment is through the use of antibiotics to eradicate the infecting bacteria.

-

In localized infections, 2% mupirocin ointment can be applied 3 times per day until the lesions have cleared.

-

Washing with an antibacterial soap daily may hasten clearance and prevent spread.

-

-

For more widespread infections, systemic antibiotics should be used.

-

The choice of these medications is the same as with impetigo.

-

The course again varies with the severity of the infection from 5 to 10 days.

-

-

Infections that have spread and become a

furuncle or abscess may need to be incised and drained, in addition to

the use of topical antibiotics. -

Measures to prevent spread should be

discussed, such as avoiding shaving (until the infection has cleared)

and avoiding the use of occlusive clothing or dressings.-

If Pseudomonas is suspected, topical treatment with silver sulfadiazine cream may be effective.

-

More widespread infections should be treated with an oral antibiotic with antipseudomonal activity such as ciprofloxacin.

-

-

Like impetigo, folliculitis is very common in the athlete due to warm, moist skin, and use of occlusive clothing.

-

Since the risk of spread is low, and

systemic complications are rare, athletes with folliculitis may

participate if the area can be adequately covered. -

If the lesions have progressed to a

draining furuncle or carbuncle, however, an athlete engaging in a

contact sport should not be allowed to participate until the lesion is

no longer draining.

genus. It is classically named based on the area of the body infected.

Tinea capitis refers to an infection on the head, tinea cruris the

groin, tinea pedis the feet, and tinea corporis the body. Like many of

the bacterial infections discussed, tinea favors warm, moist

environments, so infections are commonly seen in the web space of the

toes, between the legs, and in skin fold areas. The degree of infection

seems to depend on the infected individuals cellular-based immune

response. So many individuals may carry spores on their skin but never

develop a rash, whereas others are very prone to recurrent outbreaks.

The dermatophytes infect the superficial or keratin layer of the skin,

but may infect hair and nails as well. The fungus may also live for a

variable period of time on surfaces such as shower room floors, so

surface-to-skin transmission is common.

-

The skin lesions of tinea can take on

different appearances but are classically described as well-demarcated

patches that may have a slightly raised border.-

These patches are often erythematous and have some superficial scaling.

-

Over time, the central erythema may clear forming an erythematous ring, hence the term ringworm is often used to describe this classic tinea rash (Fig. 13-5).

-

The lesions of tinea are generally very itchy.

-

-

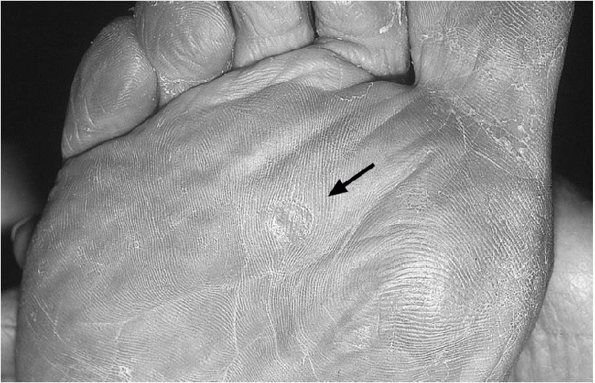

Tinea pedis commonly infects the toe web spaces, and can cause cracked, macerated, moist appearing lesions (Fig. 13-6).P.158

-

Because bacteria are prevalent on the feet, this cracked skin may provide a site for bacteria entrance and superinfection.

-

This should be considered in web space infections that are very erythematous and moist.

-

-

Tinea capitis can cause the classic skin lesions but may also cause some overlying alopecia or hair loss.

-

Tinea cruris is very common in males and typically begins in the crural folds and extends onto the inner thigh.

-

Over time, the lesion may change from erythematous to a more red-brown color (Fig. 13-7).

-

It is uncommon for tinea cruris to infect

the scrotum; therefore, if the scrotum is involved, one should consider

the possibility of another type of infection such as Candida. -

Bacteria and even repetitive friction can

cause a similar-appearing groin rash; thus, these diagnoses should be

considered when examining a groin rash.

-

-

Tinea is often diagnosed based on the location and appearance of the lesions.

-

When there is doubt, skin scrapings can be examined for the presence of the fungal organisms or hyphae.

-

The lesions are gently scraped with the edge of a glass slide or a scalpel, and these skin fragments are collected onto a slide.

-

A 10% potassium hydroxide solution is

then applied to these fragments and a coverslip applied. The potassium

hydroxide serves to lyse skin cells, thereby making the hyphae easier

to visualize. -

The slide can then be examined under low power on a microscope for the presence of hyphae.

-

Hyphae appear as branching, translucent filaments that appear to be separated into uniform segments by traversing septa.

-

|

|

Figure 13-5

Tinea corporis. Erythematous, scaly macule, with central clearing (“ringworm”). (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

|

|

Figure 13-6

Tinea pedis (“athlete’s foot”). (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

|

|

Figure 13-7

Tinea cruris (“jock itch”). (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

-

There are many different types of topical

preparations for the treatment of a tinea infection, and all are

available without a prescription. -

These medications function by disrupting synthesis of a substance in the fungal cell membrane, leading to cell lysis and death.

-

Two of the major classes of topical medications are imidazoles and allylamines.

-

The imidazole class contains medications such as miconazole, clotrimazole, and ketoconazole.

-

Allylamines contain the medication terbinafine or Lamisil.

-

-

Both classes are effective against dermatophyte infections of the skin.

-

Some studies have shown that terbinafine

may have a higher cure rate and more rapid response than the

medications in the imidazole class.

-

-

These medications are available as creams, lotions, aerosols, or powders.

-

Generally, cream or lotion is applied to the infected area twice per day until the rash clears.

-

-

Tinea infections of the nails or more

widespread infections that cannot be adequately treated with topical

medication may need a course of oral antifungal medication. -

There are many different oral agents available, of which the more common ones will be reviewed here.

-

Griseofulvin has been around for more than 20 years and is effective only against dermatophyte infections.

-

The typical adult dose for tinea

infection of the skin is 500 mg/day, for anywhere from 2 to 6 weeks,

depending on the severity of symptoms. -

The main reported side effects are gastrointestinal upset and headaches.

-

-

Ketoconazole is effective against both dermatophytes and yeast.

-

The typical adult dose for tinea infection of the skin is 200 to 400 mg/day for 2 to 4 weeks.

-

One of the most concerning side effects of ketoconazole is hepatitis, which has proved fatal in several cases.

-

Liver enzymes should be monitored before

starting oral treatment with ketoconazole and intermittently throughout

the course of treatment.

P.159 -

-

Another oral imidazole is itraconazole, which is less hepatotoxic than ketoconazole.

-

The typical adult dose for tinea infection of the skin is 200 to 400 mg/day for 2 to 4 weeks.

-

-

Finally, there is an oral form of terbinafine.

-

The typical dose for tinea infections of the skin is 250 mg/day for 2 to 6 weeks.

-

-

-

In addition to using medication, it is essential to correct factors that may predispose one to developing the infection.

-

The skin should be washed daily and

thoroughly dried before dressing, with special attention to drying skin

fold and web space areas. -

Talcum powder can be applied in the socks or underwear to absorb any excess moisture.

-

If clothes do get wet or sweaty, it is essential to change these as soon as possible.

-

Dermatophytes do survive on surfaces

other than skin; therefore, in an infected individual, all clothes

should be washed in hot (>60°C) water. -

Any old shoes or sneakers should be discarded.

-

Shower or bathroom floors should be cleaned thoroughly with bleach.

-

-

Tinea is so common in athletes that it has taken on common athletic names. Tinea pedis is commonly referred to as athlete’s foot, and tinea cruris is commonly referred to as jock itch.

-

The obvious reason for its frequency in

athletes is that an athlete often has hot sweaty skin that favors the

growth of dermatophytes. Also, athletes frequent areas such as locker

rooms and common shower rooms that can harbor dermatophytes. -

Some control measures in athletes include

not sharing equipment, or towels; avoiding occlusive clothing; wearing

shower shoes when showering or walking in common-use areas; and making

sure locker rooms and shower room areas are cleaned thoroughly between

usages. -

Because tinea is very treatable, infected

athletes are allowed to participate in contact sports as long as the

rash can be adequately covered.-

There is debate over how long an

individual must be receiving treatment before being considered

noninfectious, but 5 days is used as the general rule. -

Therefore, an athlete with a more

widespread infection, which cannot be adequately covered, should not be

allowed to participate until he or she has been treated for at least 5

days.

-

-

The NCAA requirements are slightly more

lax, requiring only a minimum of 72 hours of topical treatment of an

uncovered skin lesion, but 2 weeks of systemic treatment for a scalp

lesion before competition can be allowed.-

However, the NCAA does allow for

decisions about competition to be made on a case-by-case basis, by

physicians or certified athletic trainers.

-

-

Table 13-1 is a summary of dermatologic conditions and their treatment.

skin, often secondary to a local insult. The border of erythema

advances in cellulites. There are numerous etiologic bacteria that

cause this illness, including Streptococcus pyogenes, group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA). Cellulitis often occurs on the lower extremities or the hands,

but can occur anywhere on the dermis. An abscess is a fluctuant soft

tissue mass with overlying erythema. Abscesses are deep tissue

infections with a pocket of pus that makes the area fluctuant.

-

Diagnosis is made clinically.

-

Skin temperature and color are important clinical findings.

-

It is important to monitor the infection closely.

-

Occasionally, cellulitis may progress to or indicate an underlying abscess.

-

With the new emergence of MRSA, cultures of an abscess must be considered.

-

Monitoring the infection for clinical response remains very important.

-

The mainstay treatment of cellulitis is oral antibiotics based on underlying bacterial infection.

-

First-line antibiotics include dicloxacillin, cephalexin, and erythromycin.

-

If the infection is not responding well to oral treatment, parenteral may be necessary.

-

An abscess is treated with antibiotics, as is cellulitis.

-

It must first be incised and drained for maximal antibiotic benefits.

-

-

Infections secondary to

community-acquired MRSA are usually sensitive to Bactrim among other

antibiotics (vancomycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, and quinolones

[some resistance already documented with quino-lones]).

-

Community-acquired MRSA has recently

become a more prevalent pathogen responsible for abscesses, especially

in high school and college athletes.P.160-

MRSA was first reported on sports teams

in 1998. Other incidences on sports teams have now been more recently

reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

-

Guidelines for clearance do not exist.

-

If the lesions can be covered adequately and the athlete is afebrile, exclusion should not be the only option.

-

Many people are using similar criteria as is being used for herpes and impetigo in wrestling.

|

TABLE 13-1 SUMMARY OF DERMATOLOGIC CONDITIONS COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY ATHLETES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

to 95% of American adolescents in the United States. Although this

problem often commences at puberty, it may persist into adulthood. Up

to 12% of females and 3% of males have persistent acne through middle

age. The increased activity of the pilosebaceous glands occur secondary

to a change in androgen levels. Acne also develops as a result of

increased sebum production, pore clogging, rapid Propionibacterium acne

production, and inflammation. This disease of the skin gives rise to

eruptions of papules and/or pustules. A papule is a small, elevated

circumscribed lesion. A pustule is a pus-filled papule. Other types of

lesions that present in acne are comedones, macules, cysts, and nodules.

occurs secondary to sweat, heat, friction, and occlusion from athletic

equipment or clothing. It can be seen in the presence or absence of

acne vulgaris. Common sites include the back, shoulders, and chin.

-

The diagnosis of acne is made clinically.

-

The types of lesions often help determine the type and grade of acne in an athlete (Table 13-2).

-

Acne most frequently affects the face, but can also affect the shoulders, back, chest, upper arms, and upper legs.

|

TABLE 13-2 GRADING OF ACNE VULGARIS

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

-

Treatment of acne involves correcting one or more of the underlying processes that results in acne formation.

-

Athletes must be told that there is no

quick fix to acne, because it often takes 6 weeks to see the full

benefit of each treatment. -

Acne vulgaris responds to several treatments (Table 13-3).

-

More recent developments in acne therapy include laser therapy and newer topical retinoids (tazarotene gel).

-

Another intervention now being used with good results is photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid.

-

Acne mechanica generally responds to the following:

-

Decreasing friction, occlusion, and excessive moisture (cotton under pads, use moisture transfer material).

-

Hygienic practices (immediate postpractice showering and regular washing of undergarments).

-

Topical tretinoin may be considered if acne persists despite nonpharmacologic changes.

-

-

Athletes may present to the office or

training room for acne. Advice on predisposing factors and possible

treatment is frequently sought. -

Equipment—including chin straps, helmets,

sweatbands, and shoulder pads—can serve as a source of friction and

occlusion and contribute to acne mechanica. -

Uniforms that do not allow moisture and sweat to evaporate can result in occlusion and increased sweat production.

and are most commonly found on the hands, feet (plantar), elbows, and

knees. Warts are caused by many types of human papilloma viruses. Warts

may occur at a single location or at various locations. They can also

occur as single or multiple lesion(s). Some of these tumors can become

malignant. However, a majority of warts seen among athletes are benign.

Transmission is via contact or fomite.

|

TABLE 13-3 ACNE TREATMENTS

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

-

Diagnosis is made by history and physical findings.

-

The shape and distribution of various warts are characteristic in different subtypes.

-

Plantar warts are sharp, well-defined

hyperkeratotic lesions (single or in clusters “mosaic warts”) with a

smooth collar of thickened keratin (Fig. 13-8).-

Often upon paring or debulking these lesions, pinpoint bleeding may occur.

-

This occurrence helps differentiate plantar warts from calluses or corns.

-

-

Verrucae vulgaris are raised, round, or irregular in shape, and they are sharply demarcated (Fig. 13-9).

-

These lesions usually have a rough surface and are normally from 2 to 10 mm in diameter.

-

This type frequently occurs at sites prone to trauma (e.g., hands, elbows, and knees).

-

It may also occur on the face and scalp.

-

-

Verrucae vulgaris respond to numerous modalities:

-

Cryocautery with liquid nitrogen

-

1% salicylic acid or lactic acid

-

Daily electrodesiccation with curettage

-

Recurrence rates approach 33%

-

-

Verrucae plantaris respond to numerous modalities:

|

|

Figure 13-8

Plantar wart (verrucae plantaris). Characteristic punctate bleeding is present after paring. Note the loss of skin markings. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

|

|

Figure 13-9 Warts (verrucae vulgaris) on the knee. (Image provided by Stedman’s Medical Dictionary.)

|

-

There are no set rules against participation for athletes with warts.

-

Although not necessary for participation, occlusive dressing of the wart if on an exposed area may be considered.

moisture (perspiration or water from an outside source) in conjunction

with prolonged shearing/frictional forces. Other exacerbating factors

are poor shoe fit and/or socks that are not highly absorbent.

-

Treatment is multifactorial.

-

If possible, leave the blister intact.

-

If it is too uncomfortable or larger than

5 to 10 mm, then the fluid may be drained using a needle or a scalpel

after antiseptic preparation. -

Avoid unroofing the lesion to lower the chances of a secondary infection and decrease the degree of discomfort.

-

Although friction blisters are certainly

not sport-specific, they occur more frequently and are larger in tennis

players than in many other athletes, probably because of the

start-and-stop nature of the sport. -

Powder may help, but many athletes use emollient lotion (lubricant).

-

Acrylic socks have also been suggested to maintain dryness.

They are thickened regions of the skin that are a normal physiologic

response to multifactorial stresses. Hyperkeratosis occurs secondary to

increased mechanical stresses. Poorly fitting footwear, improper foot

mechanics, and high levels of activity are all players in the

pathogenesis of these lesions. Corns tend to be more cone-shaped and

are usually found on the dorsal and sides of the toes and feet (hard

corns; Fig. 13-10). They can also occur

between the toes (soft corn). Calluses are usually thicker and larger

than corns. They tend not to be as conical and live on the plantar

aspect of the foot (Fig. 13-11).

-

This diagnosis tends to be clinical.

-

Warts are one of the few other lesions that can mimic calluses and corns.

-

Decrease friction by avoiding improperly fitted shoes or incremental increases of activity levels.

-

After bathing, gently pumice and use lotions with lactic acid or urea to decrease the size and discomfort of calluses.

-

Symptomatic relief is recommended and can

also be accomplished by various methods of padding (i.e., lambs wool,

metatarsal pads). -

If conservative therapy fails, there are surgical procedures that can be tried.

-

Calluses under the metatarsal heads are

best managed conservatively, because metatarsal osteotomies have

unpredictable results, and the callous may transfer to an adjacent

metatarsal head.

|

|

Figure 13-10

Calluses are nonpainful, thickened patches of skin that occur at pressure points. (From Weber J, Kelley J. Health Assessment in Nursing, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

|

|

Figure 13-11

Corn (clavus). The circular central translucent core resembles a kernel of corn. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.) |

symptoms seen in an outpatient medical practice. Both viral and

bacterial agents can lead to acute pharyngitis. It has been estimated

that 10% of the cases of sore throat that present to a clinician are

related to streptococcal infection.

characterized as Gram-positive cocci that align in chains. The class of

streptococcus is then further subdivided into groups based on surface

proteins on the cell wall of the bacterium. Streptococcal pharyngitis

is most commonly caused by group A streptococcus but can also be less

commonly caused by group C and group G streptococci. The most important

task in the evaluation of sore throat is to identify patients infected

with group A streptococci so that they may be treated, thereby limiting

potential consequences of the infection.

-

Streptococcal pharyngitis occurs most commonly in the winter and spring months.

-

It is spread by direct contact with respiratory tract secretions of a person who has the infection.

-

There is an incubation period of 2 to 4 days, followed by an abrupt onset of sore throat, fever, malaise, and headache.

-

Symptoms of generalized upper respiratory

infection—including cough, hoarseness, laryngitis, and runny nose—are

usually not present. -

On physical examination, a clinician may

find tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy, tonsillar exudates, or

the appearance of pus on the tonsils. -

Because the clinical findings in

streptococcal pharyngitis can be nonspecific, laboratory testing is

required to definitively make the diagnosis. -

Studies have been done looking at

clinical predictors for strep throat to aid clinicians in making the

preliminary diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis, but the predictive

value of these factors is still unreliable. -

The most widely used clinical predictors

are looking for tonsillar exudates, tender anterior lymphadenopathy,

fever >100°F, and the absence of cough.-

If three or four of these predictors are

present, one can be sure that the throat culture will be positive for

streptococcus in 40% to 60% of the cases. -

If three or four of the predictors are absent, the throat culture will be negative 80% of the time.

-

-

The two main forms of laboratory testing

available to make the diagnosis of group A streptococcal pharyngitis

are rapid antigen testing (RAT) and the gold standard of throat culture.-

RAT kits identify streptococcal antigens

on pharyngeal swabs and can be used in office settings to obtain an

almost immediate result. -

This form of testing has improved greatly

in the last few years but still do not approach the sensitivity and

specificity of standard throat cultures. -

If a RAT kit is used, a positive result can be considered diagnostic and the patient may be treated.

-

If the result is negative, the test must

be followed by a standard throat culture to ensure that it was not a

false-negative result.

-

-

Streptococcal pharyngitis is a

self-limited infection that typically resolves on its own within 2 to 5

days after the onset of symptoms. -

There are still a number of reasons to

treat the infection, including reduced severity and duration of the

illness, reduced risk of complications from the infection, and a

reduction in the spread of the illness to others.-

Complications of group A streptococcal

pharyngitis include the development of acute rheumatic fever and

poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. -

The risk of developing either one of these complications is lowered greatly if the infection is properly treated.

-

-

Group A streptococcus has remained quite sensitive to penicillins.

-

The most cost-effective therapy is Penicillin VK 500 mg by mouth two times a day for 10 days.

-

In cases of penicillin allergic patients,

either erythromycin 500 mg four times a day for 10 days, or

azithromycin 500 mg by mouth on day 1, with 250 mg by mouth once a day

on days 2 to 5 may be used.

-

-

Athletes with streptococcal pharyngitis

are allowed to participate in sports, provided that symptoms have

resolved to the point that he or she feels physically able to do so. -

Athletes who have fevers, or who are

clinically dehydrated by examination, should be disqualified until

these symptoms resolve or have been corrected. -

Early detection and treatment can shorten

the severity and duration of symptoms, allowing quicker recovery time

and return to play. -

In the case of team sports, it is

important to stress hand washing and other common infection control

measures to help decrease the spread of the infection to teammates. -

The infected athlete should be assigned

his or her own water bottle and other personal equipment but need not

be quarantined from the team. -

Table 13-4 is a summary of infectious diseases and their treatment.

the “common cold,” are caused by a variety of viral agents and are

self-limited syndromes. Each of these viral agents cause an

indistinguishable clinical syndrome, and the identification of which

specific virus is responsible for the patient’s symptoms is irrelevant.

The most common viral agents involved in causing upper respiratory

tract infections are rhinovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza,

respiratory syncytial virus, and adenovirus. Transmission of these

agents occurs by aerosolized droplets from the respiratory tract and

direct physical contact.

-

The syndrome usually begins with mild malaise, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and sore throat.

-

Over the next 1 to 2 days, patients may develop laryngitis and cough.

-

Fever is unusual and, if present, is of low grade and usually does not exceed 100°F.

-

Infectivity is greatest at the time of maximal symptoms.

-

Physical examination may reveal boggy

nasal mucosa with clear rhinorrhea, serous middle ear effusions without

erythema, and an erythematous pharynx without exudate. -

Lung sounds should be clear without any coarseness or focal consolidation.

-

The mainstay of treatment of viral upper respiratory syndromes is palliative.

-

Acetaminophen or ibuprofen may be used for myalgias and low-grade fever.

-

Nasal congestion may be relieved with oral decongestants such as pseudoephedrine.

-

-

Patients should be sure to maintain adequate hydration and rest.

-

In some studies, supplementary vitamin C

has been shown to decrease the duration of symptoms related to the

common cold and may be a reasonable and safe treatment option.

-

Similar to streptococcal pharyngitis,

athletes with viral upper respiratory infections may participate if

they feel physically able to do so. -

It is important for the participating

athlete to ensure good hydration because the illness may lead to

dehydration from low-grade fever or poor oral intake. -

Also, it is quite important in team

settings that hand washing, reduced finger-to-nose contact, and

isolation of water bottles be done to prevent spread of the infection

to other teammates.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and is characterized by the triad of fever,

tonsillar pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. The infection is most

common in those 10 to 19 years of age. There is also a higher incidence

of the illness in populations of young adults who are in close contact,

such as high school and college students.

and replicates in B lymphocytes. The incubation period of the virus is

4 to 8 weeks, and the virus can persist in the oropharynx of infected

individuals for up to 18 months after clinical recovery. Actually, most

primary EBV infections are subclinical infections and usually go

undetected.

-

The typical presentation of infectious mononucleosis often begins with malaise, headache, and poor appetite.

-

It then progresses to the triad of moderate-to-high fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy.P.165

-

Pharyngitis is frequently accompanied by tonsillar exudate and can be confused with the appearance of streptococcal pharyngitis.

-

The characteristic lymphadenopathy is

symmetric and typically involves the posterior cervical chain, which

lies posterior and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

-

-

Other clinical findings of the syndrome

may include severe fatigue, splenomegaly, a generalized maculopapular

rash (which is more common with concomitant antibiotic use), hemolytic

anemia, and thrombocytopenia. -

Patients with suspected infectious

mononucleosis by history and physical examination should have both a

complete blood count with differential and heterophile antibody test

(monospot) done to confirm the diagnosis.-

The complete blood count will typically

reveal a mildly elevated total white blood cell count composed of 60%

to 70% lymphocytes, with greater than 10% being atypical.-

Atypical lymphocytes are not specific to

EBV infections but, when combined with the clinical picture, can be

quite suggestive of the diagnosis.

-

-

Heterophile antibodies are antibodies that react to antigens from unrelated species.

-

In the case of mononucleosis, the test is performed using equine erythrocytes as the substrate.

-

The heterophile antibody test is both sensitive and specific for infectious mononucleosis.

-

A patient will develop detectable heterophile antibodies within 1 week of the onset of symptoms.

-

These antibodies will peak from 2 to 5 weeks and may persist in some patients for up to 1 year.

-

A negative heterophile antibody test may

occur early in the course of the illness, and if the diagnosis is still

in doubt, repeating it later may result in a positive test. -

In a few rare instances, the heterophile antibody test will reveal a false negative.

-

In these instances, EBV-specific antibody

testing can be obtained, which tests for antibodies directed against

antigens on the EBV virus capsid.

-

-

|

TABLE 13-4 SUMMARY OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY ATHLETES

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

Supportive care remains the mainstay in treatment of infectious mononucleosis.

-

Acetaminophen or nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory medication can be used for the treatment of fever,

myalgias, and throat discomfort related to the infection. -

Adequate rest is also important, but complete bed rest is not necessary.

-

More recently, attention has been focused on the use of corticosteroids in infectious mononucleosis.

-

Study results suggest that prednisone and

other corticosteroids may be helpful in decreasing pharyngeal and

lymphoid swelling but do not have any significant effect on the course

of the infection.

-

The two most important factors to

consider when deciding an athlete’s return to play after infectious

mononucleosis are spleen size and the likelihood of a decline from

relapse of symptoms. -

Splenic rupture accounts for the greatest risk of both morbidity and mortality in athletes with infectious mononucleosis.

-

As the spleen enlarges from the

infiltration of lymphocytes, it becomes increasingly fragile and may

lead to spontaneous rupture or rupture related to minor abdominal

trauma. -

It has been estimated that greater than 50% of patients with primary EBV infection have splenomegaly as part of the illness.

-

These changes in the spleen seem to be

most prominent from day 4 to day 21 of the illness, with the risk of

splenic rupture being highest at this time as well. -

It is recommended that all athletes

should have an absolute minimum disqualification of 21 days from the

onset of the illness to minimize the possibility of injury to the

spleen. -

After day 21 of the illness, a careful physical examination should be performed focusing on assessment of the spleen size.

-

One of the major difficulties in

determining spleen status is that the physical examination of the

spleen is difficult and, in many cases, the spleen is enlarged even

when it is not palpable on physical examination. -

Abdominal ultrasound is the study of

choice to assess spleen size in patients with infectious mononucleosis,

but experts differ in opinion on whether an ultrasound is required

before allowing an athlete to return to play. -

If an athlete’s spleen status is in

question, especially if the athlete participates in a contact sport,

the treating physician should not hesitate to obtain an ultrasound to

ensure that spleen size is normal. -

At this time, however, no formal

recommendation has been made for the use of abdominal ultrasound in the

return-to-play decision for athletes with mononucleosis. -

If the spleen remains enlarged by either

physical examination or ultrasound, an athlete should be held from

participation until splenic enlargement resolves.

-

-

Another question to consider when

deciding to allow an athlete to return to play is whether the viral

syndrome has resolved enough to prevent relapse of the symptoms of the

illness.-

The major concern is that too rapid of a

return to activity may exacerbate the athlete’s symptoms lending to a

longer time of recovery. -

In general, all athletes should have a 3-week disqualification period.

-

If symptoms of the viral syndrome are

resolving, and no further splenic concerns exist, the athlete may begin

a graded return to training leading up to full participation.

-

caused by the influenza virus. The influenza virus is grouped into

three types: A, B, and C. Influenza A and influenza B are further

divided into various subtypes that cause the typical infection

associated with the flu. Influenza causes yearly epidemics from

December to March in temperate climates and can cause significant

morbidity and mortality. The virus replicates in the epithelial cells

of the respiratory tract and is spread via respiratory secretions

expelled during coughing, sneezing, or talking. The disease can spread

very quickly in close quarters such as schools, nursing home, or locker

rooms.

to 4 days. Adults are typically infectious 1 day before symptoms appear

and, on average, 5 days into the illness. Children may be infectious

for slightly longer.

-

The main challenge in diagnosis is

differentiating the influenza virus and its symptoms from other common

upper respiratory viruses, both of which are very prevalent during the

winter months. -

Some of the classic symptoms of influenza are fever (generally 100° to 104°F), myalgias, and cough.

-

These symptoms tend to be more common in influenza than in other viruses that cause colds.

-

-

In addition, a patient may experience

congestion, sore throat, anorexia, and malaise similar to symptoms with

other common winter viruses. -

Another possible clue to differentiating influenza from other viruses is the acuity of symptoms.

-

The symptoms of influenza tend to occur

quickly, whereas other viruses tend to have a more gradual onset with

symptoms that occur mildly, and then progress over several days. -

Flu symptoms also tend to resolve quickly, lasting on average 5 to 7 days; however, malaise can sometimes persist longer.

-

-

Mortalities related to the influenza

occur every year typically in individuals over 65 or young children.

From 1990 to 1999, there were approximately 36,000 deaths attributed to

influenza. -

The diagnostic tests available to aid in

the diagnosis of influenza include viral culture, serology, polymerase

chain reaction, enzyme immunoassay, and direct immunofluorescence.-

Many of these tests are not practical

because the results take too long to return, and some testing methods

only occur in specialized laboratories. -

A viral culture is important

epidemiologically, as it can identify the exact subtype of influenza,

although it will not aid in treatment decisions because the results

usually take 5 to 10 days to return. -

There are several rapid test kits

available that use enzyme immunoassay and immunofluorescence techniques

and generally return results anywhere from 10 to 30 minutes. Most of

these rapid tests are more than 70% sensitive and more than 90%

specific.

-

-

One of the best ways to limit morbidity and mortality related to influenza is widespread vaccination.

-

Each year, the subtypes of influenza

thought to be most prevalent in the given year are determined, and

vaccines are created against these subtypes. -

The vaccine is available as inactivated

(killed virus), which is available via injection, and live attenuated

virus is available via a nasal spray. -

Typically, those at highest risk for

complications—such as infants, the elderly, and individuals with

chronic disease, as well as health care workers—are vaccinated as early

as the vaccine becomes available. -

Others can be vaccinated throughout the flu season, depending on the amount of vaccine available in a given year.

-

The main side effect of vaccination is a

mild flu-like illness, which can be more pronounced with use of the

live attenuated vaccine.

-

-

There are medications available that may

lessen the time course of influenza symptoms, but these need to be

started when the virus is actively replicating usually within the first

48 hours of symptom onset. -

Amantadine and rimantadine have been

available the longest; although their mechanism of action is not

entirely understood, they are believed to inhibit an ion channel on the

influenza A virus.-

The major drawback is that these medications are effective only against influenza A.

-

They also may cause gastrointestinal or central nervous system side effects that may limit their use.

-

-

In 1999, the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration approved the neuraminidase inhibitors zanamivir

(Relenza) and oseltamivir (Tamiflu) for the treatment of influenza.-

Neuraminidase is a viral glycoprotein necessary for the replication of influenza A and B.

-

The standard adult dose of oseltamivir is 75 mg twice/day for 5 days.

-

Zanamivir is administered by oral

inhalation, and so it needs to be used with caution in those with

existing asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, because it

may cause bronchospasm.-

The standard adult dose of zanamivir is 10 mg delivered via an inhalation device twice per day for 5 days.

-

-

The benefit of these medications is that they are effective against both influenza A and B. The main drawback is the cost.

-

In addition to their use for treatment of

influenza, amantadine, rimantadine, and oseltamivir have been approved

for chemoprophylaxis of close contacts of individuals diagnosed with

influenza.

-

-

Outbreaks of influenza can spread quickly

among teams, so it is important to make the diagnosis early so that the

infected individual may be removed from contact with teammates. -

Infected individuals should avoid contact with others for 5 days.

-

However, if treatment is begun within the first 48 hours of symptom onset, the infectious period is likely lessened.

-

-

There are no good data on the duration of the infectious period in a treated individual, but a general rule is 3 days.

-

Unvaccinated, close contacts of individuals who are diagnosed with influenza may undergo chemoprophylaxis to prevent infection.

-

Infected individuals may return to competition when they are symptomatically improved, which may take 3 to 10 days.

-

Again, the malaise from influenza may last longer than 1 week and may be a limiting factor in return to activity.

-

An individual should not be allowed to return if they are still febrile or clinically dehydrated.

-

-

If the supplies of vaccine allow,

vaccinating teams who are active in the winter months early in the flu

season is the ideal way to prevent team epidemics.

AL, Peter GS, Kaplan EL. Diagnosis of strep throat in adults: are

clinical criteria really good enough? Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:126.

RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Principles of appropriate

antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Intern

Med 2001;134:509.

WL Jr, Dightman L, Dworkin MS, et al. Pinning down skin infections:

diagnosis, treatment, and prevention in wrestlers. Phys Sportsmed

1997;25.

H, Stangerup SE, Stangerup M, et al. Hepatosplenomegaly in infectious

mononucleosis, assessed by ultrasonic scanning. Laryngol Otol

1986;100:573-579.

TR, Chalmers TC, Frenkel LD, et al. Ascorbic acid for the common cold,

a prophylactic and therapeutic trial. JAMA 1998; 231:1038.

V, Mottur-Dilson C, Cooper RJ, et al. Principles of appropriate

antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults. Ann Intern Med 2001;

134:506.

KP, Quinlan EC, Casey TV. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen secondary

to infectious mononucleosis. Intern Surg 1972; 57:171-173.

E, Aurelius E, Brandell C, et al. Acyclovir and prednisolone treatment

of acute infectious mononucleosis: a multicenter, double blind,

placebo-controlled study. J Infect Dis 1996;174:324.