Medical Concerns of The Team Physician

issues in athletes that can range from dermatologic conditions to

cardiac anomalies. It is important for the team physician to be aware

of common medical conditions that affect athletes, as well as their

impact on safe participation. A sound understanding of these conditions

allows for an accurate assessment and initiation of an effective

treatment program. Common medical conditions that affect athletes are

listed below with a focused overview, and pearls to diagnosis and

effective treatment options are outlined. Keys to return to play and

clearance are addressed for relevant conditions.

exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB), describes the transient airway

narrowing after exercise or physical activity that occurs in some

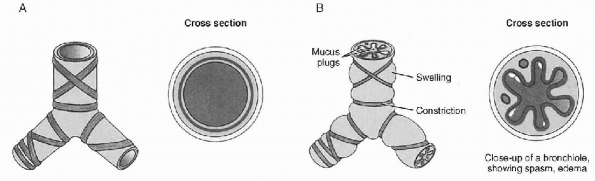

individuals. Asthma (Fig. 12-1) is a common

respiratory disease in many children and young adults, and exercise is

one of the most common precipitating factors of an acute attack. EIB is

caused by the loss of heat, water, or both from the lungs during

exercise, as the ventilated air during exercise is drier and cooler

than that in the respiratory tree. Between 80% and 90% of patients with

asthma may also have EIB. However, there are many patients who only

have bronchospasm associated with exercise. Stimuli thought to be

associated with triggering EIB include environmental pollutants (such

as found in indoor ice arenas, including a high level of nitrogen

dioxide and carbon monoxide) and sulfur dioxide. Although swimmers have

generally been described to be at lower risk secondary to their warm,

humid environment, chlorine compounds in swimming pools have been

described as a possible trigger in swimmers who do develop symptoms of

EIB. A high prevalence has also been found in elite ski racers who race

in cold/dry ambient conditions and distance runners associated with

respiratory allergies. Other stimuli may include viral illness or

cigarette smoking.

-

Athletes complain of shortness of breath,

chest tightness, coughing, or wheezing associated with participation in

their sport or with exercise.P.136-

They may notice a decrease in their exercise endurance as well.

-

-

Symptoms typically occur during or

shortly after onset of exercise, peak 8 to 15 minutes after exercise,

and spontaneously resolve within 30 to 60 minutes.-

A refractory period of up to 3 hours

after recovery is often seen, during which time there is less

bronchospasm seen with exercise.

-

-

When initially evaluating an athlete for EIB, it is important to distinguish between exacerbation of chronic asthma and EIB.

-

Types and levels of exercise that precipitate the problem and the exact symptoms that develop should be addressed.

-

Common physical examination findings observed include cough and expiratory wheezing after exercise.

|

|

Figure 12-1 Asthma. (A) Normal bronchiole and (B)

bronchiole under asthma attack. (From Willis MC. Medical Terminology: The Language of Health Care. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1996: 233.) |

-

Confirmation of the diagnosis of EIB is

accomplished by recording a fall in the forced expiratory volume in 1

second of 15% or more after an exercise challenge test with spirometry. -

A level of exercise must generate 85% of

an athlete’s maximum heart rate and should last for 4 to 8 minutes to

maintain an appropriate ventilatory rate.-

This can be accomplished by having the athlete run on a treadmill or pedal on an exercise bike to try to evoke symptoms.

-

This may be more difficult in elite

athletes or in those individuals who have an environmental stimulus

(i.e., who may require testing in their sport-specific environment to

elicit their symptoms).

-

-

Spirometry is performed at 3- to 5-minute intervals up to 30 minutes after this level of exertion is reached.

-

If the ability to do exercise challenge

testing is logistically difficult because of access to spirometry or

space, consider use of peak flows recorded before and during their

sports participation. -

Differential diagnosis includes exacerbation of chronic asthma and vocal cord dysfunction.

-

In chronic asthma, there may be night

symptoms or symptoms seen at times other than with exercise and may

necessitate more intensive treatment. -

With vocal cord dysfunction, inspiratory rather than expiratory wheezing (as well as stridor) may be seen.

-

If the diagnosis is in question, consider referral to an ear, nose, and throat specialist for evaluation.

-

The main treatment goal of EIB is focused

on prevention and/or modifying the severity. This can be accomplished

through a variety of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches. -

Some nonpharmacologic suggestions include

modifying the environment in which the exercise occurs, such as

avoiding cold, dry air by exercising in warmer and more humid

conditions. -

Type of exercise should also be considered, as more severe symptoms usually are related to greater intensity and duration.

-

High-minute ventilation activities (long

distance running and cycling) and activities taking place in a cool,

dry climate (ice hockey, figure skating, speed skating) are more likely

to induce EIB.

-

-

Warming up before exercise may allow

competitive participation to occur during the refractory period where

less bronchospasm is present and may decrease development of EIB. -

Pharmacologic treatment should be

considered if there is no improvement with exercise modifications or if

the athlete’s particular sport does not allow for this type of

modification. -

The most common first-line therapy for EIB is inhaled β2-adrenergic agonists.

-

These are short-acting bronchodilators

that can be used 5 to 30 minutes before exercise for prophylactic use,

as well as during exercise for symptomatic relief if needed.

-

-

Other treatment alternatives include a long acting β2-agonist, which can be used 30 to 60 minutes before exercise and can last for up to 12 hours, as well as leukotriene inhibitors.

-

Other medications used include cromolyn sodium and theophylline.

-

If common EIB therapies are not causing

improvement in symptoms, re-evaluation for possible exacerbation of

chronic asthma should be considered. -

It is important to consider that some of

these drugs may be banned by the National Collegiate Athletic

Association (NCAA) or the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and

therefore the medication used may vary, depending on the athlete’s

level of participation and the sport involved.

-

An athlete who has been appropriately diagnosed and is under adequate treatment is cleared to participate as tolerated.

-

If pharmacologic treatment is used,

athletes should carry the medication with them at all times if they are

involved in any form of exercise. -

Review of NCAA, IOC, or relevant

governing body guidelines should be taken before allowing a specific

treatment to be used while in competition.

generally characterized by a spectrum of symptoms that occur with

physical activity, ranging from milder cutaneous manifestations to more

severe findings of hypotension, syncope, and death. Ingestion of

certain foods (seafood, celery, wheat, and cheese) or medications

(aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) before exercise has

been considered as possible predisposing factors. Although the severe

symptoms are rare, urticaria is much more common and may affect 10% to

20% of the population at some time.

-

With exercise-induced urticaria, athletes report symptoms of cutaneous warmth, erythema, and pruritus during or after exercise.

-

If symptoms progress to wheezing, dyspnea, or syncope, exercise-induced anaphylaxis should be considered.

-

A personal history of atopy may help support the diagnosis.

-

The exercise challenge test can help diagnose an athlete with suspected exercise-induced anaphylaxis.

-

This can be done by using a treadmill or exercise bicycle under controlled conditions with emergency equipment available.

-

-

A positive test, with reproduction of the

signs and symptoms, helps confirm the diagnosis; however, a negative

test is nondiagnostic, as the athlete may still have exercise-induced

anaphylaxis that was not triggered.

-

Similar to EIB, modification of activities that may precipitate the event is an important first-line consideration.

-

Athletes should have an EpiPen or anaphylaxis kit in their possession or near by while exercising.

-

Acute reactions may also be treated with antihistamines and steroids in addition to the epinephrine.

-

If an athlete has a history of life-threatening anaphylaxis, this is generally a contraindication to participation.

-

There are, however, no firm guidelines,

and switching to a less strenuous sport may be considered if risks and

benefits are thoroughly reviewed. -

In less serious situations, participation

can be allowed as long as precautions are undertaken, including EpiPen

and resuscitation equipment.

disease that is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young

athletes. It is relatively common in the general population, affecting

approximately 1 in 500 people. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant

trait. It is caused by the mutation of a gene that encodes proteins of

the cardiac sarcomere. Currently, there are three mutant sarcomeric

genes that predominate: β-myosin heavy chain, cardiac troponin T, and

myosin-binding protein C.

asymptomatic to sudden death. Its pathologic feature is left

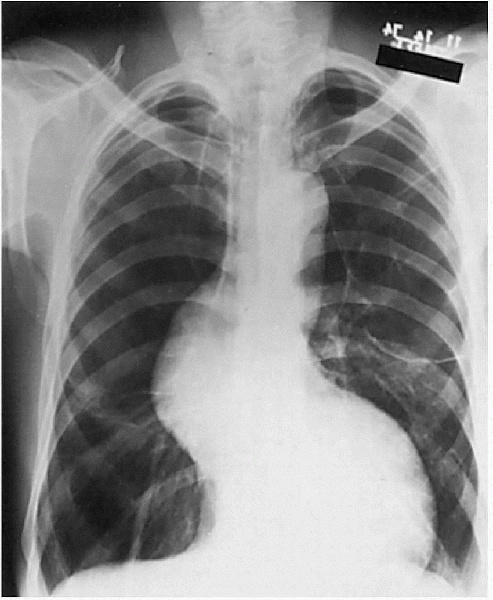

ventricular wall hypertrophy without dilatation (Fig. 12-2).

In the absence of other causes, this can be diagnostic of HCM. On

histologic evaluation of the cardiac muscle at autopsy, cardiac muscle

cell disorganization is seen. Screening during the preparticipation

examination has become a focus as to a way to prevent many of the

sudden cardiac deaths that result from HCM.

-

The wide range of presentations seen in HCM makes diagnosis a challenge.

-

Athletes may present with symptoms such

as dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, or arrhythmia. Any of these symptoms

should heighten consideration for a cardiac cause, such as HCM. -

The presentation may be sudden death in a young athlete after strenuous exertion.

-

Sudden death is most common in children and young adults ages 10 to 30.

-

-

The preparticipation screening

examination may be the opportunity to detect an athlete who is at high

risk for HCM before the unfortunate event of sudden death occurs.-

Screening questions should include a family history of cardiac disease; specifically, early cardiac death before the age of 50.

-

The athlete should be asked about history of chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, or near-syncopal episodes in relation to exercise.

-

|

|

Figure 12-2

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The heart has been opened to show striking asymmetric left ventricular hypertrophy. The interventricular septum is thicker than the free wall of the left ventricle and impinges on the outflow tract. (From Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.) |

-

Any positive history findings during the

screening examination should cause increased awareness during the

physical examination; but, because many athletes are asymptomatic, the

cardiac examination may be your one opportunity for early detection of

HCM. -

Clinical findings include a systolic

ejection murmur at the left sternal border that increase with

provocative maneuvers that decrease venous return, such as Valsalva

maneuver or going from a squatting to a standing position. -

Any murmur grade III/IV or greater should be further investigated.

-

Most patients with HCM do not have

obstruction to flow under resting conditions; therefore, physical

examination is not reliable on its own as a screening tool.

-

The diagnosis can be reinforced by diagnostic tests such as an electrocardiogram (ECG) or a two-dimensional echocardiogram.

-

Findings on ECG include criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy.

-

An echocardiogram shows left ventricular wall thickening (LVWT) with a nondilated left ventricular chamber.

-

Findings of LVWT >15 mm are highly suggestive of HCM.

-

HCM should be strongly considered in any

male athlete with LVWT >12 mm and in any female athlete with LVWT

>11 mm with a nondilated left ventricle. -

LVWT between 13 and 15 mm is a diagnostic gray zone.

-

-

Stress echocardiography may also help distinguish between athlete’s heart and HCM.

-

Some athletes who have undergone intense

physical training may have a physiologic increase of LVWT >15 mm,

but they will demonstrate an absence of left ventricular outflow tract

gradient on exercise echocardiography. -

If there is diagnostic uncertainty, genetic testing can be definitive.

-

It is not routinely available because of its complexity, cost, and time consumption.

-

-

-

Pharmacologic options for treatment of symptomatic patients include β-adrenergic blocking drugs and verapamil.

-

β-Blockers have a negative inotropic

effect, therefore prolonging diastole and allowing increased

ventricular filling. This helps to improve symptoms such as chest pain

and dyspnea and allows improvement in exercise tolerance. -

Verapamil also helps with symptoms by improving ventricular filling.

-

In asymptomatic patients, there is no evidence that either β-blockers or verapamil protect against sudden cardiac death.

-

Exceptions that may be treated are asymptomatic patients with significant outflow tract obstructions.

-

-

Atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia to develop in patients with HCM and is often treated with amiodarone.

-

Nonpharmacologic therapy for unresponsive HCM includes myomectomy and alcohol septal ablation.

-

Dual-chamber pacing and implantable cardiac defibrillators have also been used.

-

The 36th Bethesda Conference recommended

that all persons with HCM, even those with no symptoms or who have

received treatment, be excluded from competitive sports, with the

possible exception of low-intensity athletics (IA). -

They found no good evidence that exceptions should be made to this policy.

often unrecognized cause of sudden cardiac death, accounting for up to

20% of cases in young athletes. A congenital coronary anomaly is the

ectopic origin of a coronary artery. It is classified based on the

artery involved and its origin and path. Many of these types produce

few or no symptoms, but others can be more serious and even cause

sudden death. Some of the types described include the left coronary

artery arising from the right sinus of Valsalva, the right coronary

artery arising from the left sinus of Valsalva, or the absence of the

left coronary artery/single coronary artery (attributed to the death of

“Pistol Pete” Maravich, a previous hall-of-fame basketball star).

-

There is frequently the absence of any

symptoms, therefore making it difficult to diagnose. If there are

symptoms present, they may include chest pain or syncope. -

Often, there is no associated physical

examination findings associated with a congenital coronary anomaly,

once again explaining the difficulty in diagnosis. Occasionally, a

murmur may be present. -

Congenital coronary anomalies often are not diagnosed until autopsy.

-

If the patient has symptoms, workup may

include an electrocardiogram (usually normal) or a two-dimensional

echocardiography with color Doppler imaging (which may reveal the

coronary artery anomalies). -

If the echocardiogram is nondiagnostic,

coronary angiography, ultra-fast computed tomography (CT) and/or a

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be necessary to delineate.

-

The patient should be referred to a cardiothoracic surgeon for potential surgery to reduce the risk of cardiac death.

-

Possible options include coronary artery bypass grafting or coronary artery reimplantation.

-

The 36th Bethesda Conference recommended

that participation in competitive sports should be prohibited once

congenital anomalies are detected. -

Three months after successful surgical

treatment, participation could resume, assuming the athlete has no

ischemia, ventricular or tachyarrhythmia, or dysfunction during maximal

exercise testing.

general population is considered to be arrhythmias. In young persons

without any identifiable structural heart defect, long QT syndromes

(LQTS) are common causes. There are multiple genes identified that

encode cardiac ion channels (mostly potassium and sodium) that cause

LQTS. It occurs as an inherited disorder or can be acquired. One cause

of acquired LQTS is the use of certain medications, such as

antiarrhythmics, antihistamines, psychotropic drugs, antifungal drugs,

and macrolide antibiotics. It can also be acquired through electrolyte

disturbances such as hypokalemia. The result is prolongation of

ventricular repolarization, which can lead to fatal arrhythmias, most

commonly from polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular

fibrillation.

-

Patients may complain of palpitations or a syncopal episode.

-

Potentially, the presentation could be cardiac arrest or sudden death.

-

Review of the athlete’s family history during preparticipation screening is important.

-

If a patient presents with symptoms, a review of their current and recent medications should take place.

-

In the symptomatic patient, a cardiac arrhythmia will be detected, possibly ventricular tachycardia.

-

LQTS is usually diagnosed with an ECG.

-

There is a prolonged QT interval with correction for heart rate QTc of >460 to 480 msec.

-

There is also often a relative bradycardia, T-wave abnormalities, and episodic ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

-

Genetic testing can also be done to determine the genotypic type.

-

The 36th Bethesda Conference recommended

excluding from all competitive sports (except class IA category) anyone

who has had cardiac arrest outside of a hospital or who has had a

suspected syncopal episode precipitated by LQTS. -

Asymptomatic patients with QT prolongation may participate in IA sports.

-

Patients identified with QT prolongation

by genetic testing who are genotype-positive/phenotype-negative LQTS

may participate in competitive sports, with the exception of swimming. -

Patients with LQTS/pacemaker should not

participate in collision or contact sports as a result of risk of

damage to the pacemaker. The presence of an implantable cardiac

defibrillator (ICD) should restrict individuals to class IA activities.

condition observed in competitive athletes. A blood pressure reading in

adults over the age of 18 should be below 120/80. A reading above that

is considered hypertensive. When dealing with patients under 18,

hypertension is defined as average systolic or diastolic levels greater

than or equal to the 95th percentile for gender, age, and height. Blood

pressure measurement should be a standard part of any examination to

clear competitive athletes for competition.

VII classifies blood pressure into normal (<120/80), prehypertension

(120 to 139/80 to 89), stage 1 hypertension (140 to 159/90 to 99), and

stage 2 hypertension (≥160/100).

-

When evaluating an athlete with

hypertension, the history should include questions about diet, salt

intake, caffeine use, excessive alcohol consumption, stimulants,

decongestants, herbs, dietary supplements, and illicit drugs. -

Other things that may need to be

considered are stress levels, gender (male >female), race (blacks

>whites), and family history of hypertension.

-

When measuring blood pressure, proper cuff size and technique should be used to ensure accuracy.

-

Diagnosis should not be made on an isolated reading in the office, because many patients will exhibit “white coat” hypertension.

-

At least three separate readings on separate days should be documented before labeling someone as hypertensive.

-

Laboratory tests to exclude secondary

causes of hypertension or to identify end-organ damage include a

complete blood count, sodium, potassium, blood urea nitrogen,

creatinine, glucose, cholesterol levels, urinalysis, and ECG.

-

Nonpharmacologic treatments include dietary and lifestyle changes.

-

Some specific recommendations may include

a decrease in sodium intake and an increase in potassium intake,

avoiding stimulants and caffeine use, regular aerobic exercise, and

weight loss. -

If stress is a concern, relaxation techniques may be tried.

-

Regular cardiovascular exercise can also assist in lower blood pressure.

-

-

Hypertension not controlled with lifestyle changes often requires use of pharmacologic treatment.

-

There are multiple pharmacologic choices

available but some may have an adverse affect on exercise tolerance,

and some are banned for use by the IOC or the NCAA. -

Possible classes of drugs include

thiazide diuretics, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers,

and α-blockers. -

Choices may be driven by their side effects and their effect on heart rate and exercise tolerance.

-

Athletes tend to tolerate thiazide diuretics and ace inhibitors best.

-

β-Blockers tend to cause exercise intolerance and therefore are not tolerated as well.

-

-

Before individuals begin a competitive training program, they should have undergone an evaluation of their blood pressure.

-

The 36th Bethesda Conference defines

multiple different recommendations with regard to participation based

on the level of the blood pressure and the presence of end-organ

dysfunction. -

Mild-to-moderate hypertension is usually not a contraindication to athletic participation in the absence of end-organ damage.

-

Certain high-intensity sports may need to be restricted until hypertension is controlled.

-

It is important to make sure any

pharmacologic treatment is not classified as a banned substance with

the appropriate governing board.

-

Multiple cardiac congenital anomalies can

exist in athletes that require individual evaluation and consideration

with regard to athletic participation. -

Some examples include atrial septal

defect, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus,

coarctation of the aorta, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the

great vessels, and Ebstein’s anomaly. -

Many of these may have been present at birth and were surgically corrected.

-

Specific recommendations are made with regard to active or corrected congenital cardiac anomalies before athletic clearance.

-

It is important to ask about history of

any cardiac problems, and the Bethesda recommendations should be

reviewed before clearance for participation in athletics.

-

Valvular heart disease may be detected by the presence of a cardiac murmur or characteristic physical examination findings.

-

Some examples include mitral stenosis,

mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, tricuspid

regurgitation, tricuspid stenosis, mitral valve prolapse, and

prosthetic heart valves. -

Athletes should be referred to the

appropriate physician who is comfortable in managing these diseases

before clearance to play should be allowed. -

The Bethesda recommendations offer

guidelines to consider in asymptomatic individuals, and symptomatic

individuals will often need referral for consideration of valvular

replacement or repair.

-

ARVD is a disorder that is characterized by ventricular arrhythmias and structural abnormalities of the right ventricle.

-

It is caused by progressive replacement of the myocardium with fibrofatty tissue.

-

Symptoms may include palpitations, syncope, or sudden cardiac death, although the patient may be asymptomatic.

-

Treatment usually consists of antiarrhythmic drugs or use of an ICD.

-

Recommendations from the 36th Bethesda

Conference state that athletes with ARVD should be excluded from most

competitive sports, with the possible exception of those of

low-intensity (class IA).

-

It is thought that regular cardiovascular activity reduces the risk of CAD.

-

In those individuals with known CAD

though, risk stratification should be undergone before clearance for

intense physical activity. -

Evaluation may consist of a maximal treadmill or exercise test to assess their exercise capacity.

-

ECG stress testing before participation in athletics should be included for those at moderate to high risk for CAD.

-

More specifically, this includes men

>40 to 45 years old or women >50 to 55 years old with 1 or more

independent coronary risk factors. -

A risk factor would be

hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol >200 mg/dL, low-density

lipoprotein >130 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein <35 mg/dL in

men, or < 45 mg/dL in women), systemic hypertension (>140/90),

cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, a history of myocardial

infarction, or sudden cardiac death in a family member <60 years of

age, any symptoms of cardiac disease, or anyone ≥65 years of age in the

absence of risk factors. -

The 36th Bethesda Conference has made

recommendations for intensity of sports activities that should be

allowed based on the patient’s risk stratification level. -

Athletes with mildly increased risk can

usually participate in low-to-moderate intensity sports, but should be

re-evaluated annually for risk stratification. -

If an athlete is in the increased risk group, he or she is generally restricted to low-intensity sports.

-

Athletes with a recent myocardial infarction should avoid training until cleared by the cardiologist.

-

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant

connective tissue disorder that consists of a variety of clinical

manifestations of the skeletal system (tall stature, arachnodactyly,

increased arm span to height ratio, ligamentous laxity, and chest wall

deformities) and ocular injuries (lens dislocation). -

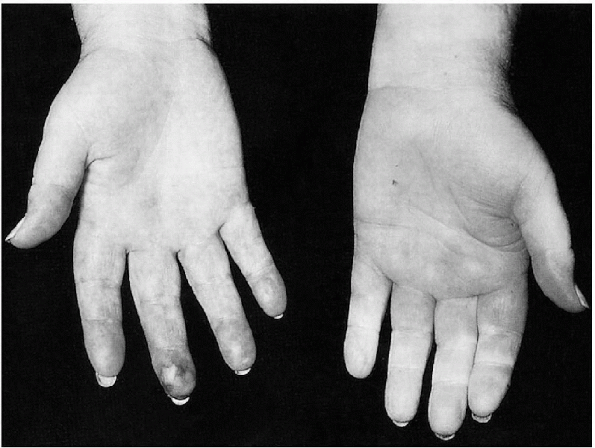

The cardiovascular system may also be affected by aortic dilatation and possible dissection (Fig. 12-3).

-

In athletes with suspected Marfan

syndrome, they should undergo further evaluation with an echocardiogram

to evaluate the aortic root. -

Certain restrictions in activities are recommended based on the history, symptoms, and aortic root size.

-

Referral to a cardiologist or a

specialist in evaluation of Marfan syndrome should be considered if

there is any question about diagnosis or decisions on recommended

activity levels.

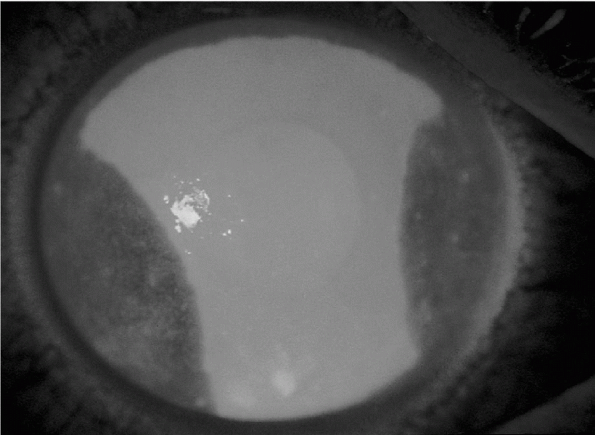

stress and causes ischemia of the fingers and toes. It was first

described in 1862 by Maurice Raynaud as a phenomenon of cold-induced

digital pallor followed by cyanosis and erythema. Fingers are the most

commonly affected (Fig. 12-4),

followed by the toes. Other potential sites include the tongue, nose,

ears, and nipples. It can be seen worldwide but has a higher prevalence

in cold weather climates. Females have a higher risk for development of

the disorder than do males. Having a family history of the disorder or

having a personal history of related connective tissue disorders are

also risk factors.

|

|

Figure 12-3

Marfan syndrome with hyperinflation, bullous changes, dilated tortuous aorta, and “tall” lungs. (From Crapo JD, Glassroth JL, Karlinky JB, et al. Baum’s Textbook of Pulmonary Diseases, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.) |

|

|

Figure 12-4

Hallmarks of Raynaud’s disease are color changes. (From Effeney DJ, Stoney RJ. Wylie’s Atlas of Vascular Surgery: Disorders of the Extremities. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1993.) |

is no known underlying illness) or secondary (a related disorder is

detected). A frequent association is seen between scleroderma and

Raynaud’s phenomenon. Other secondary causes include occupational

exposure to mechanical vibration, medications (chemotherapeutic

agents), and more widespread vasospastic processes. Typically, primary

disease is seen in the second or third decade of life, and secondary

disease is usually after the age of 40.

-

When obtaining a history from the

athlete, details should be obtained regarding occupation, sports

participation, medical history, and medications. -

The description of the digits may consist

of initial pallor caused by digital artery vasoconstriction, followed

by cyanosis from slow blood flow, and then a reactive hyperemia as the

vessels reopen in response to warmth. -

Some athletes may notice only cyanosis or may observe the entire spectrum of findings.

-

Typically, it will initially involve only one or two fingers and may then progress to all of them.

-

-

Sometimes the symptoms will resolve spontaneously, and others will only respond to warming.

-

Often, the clinician does not witness the event, as it has resolved by the time of presentation.

-

As team physicians may be on the

sidelines during coldweather sports, it is possible that the athlete

may present with the initial pallor or cyanosis for advice. -

Physical examination should consist of careful inspection of all of the digits on the hands and feet and peripheral pulses.

-

Further workup should ensue in an athlete with the above history and examination findings to look for potential primary causes.

-

Diagnostic tests should include a

complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, chemistry

profile, autoantibody screen, urinalysis, and radiographs of the hands

and chest. -

Other rheumatologic testing may be necessary to rule out related disorders.

-

Differential diagnosis should include

peripheral vascular disease, Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis

obliterans), polycythemia, scleroderma, systemic lupus, CREST syndrome (calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia), thoracic outlet syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, occupational injury, and drugs (chemotherapeutic agents).

-

Differentiation between primary and secondary diseases should be determined, as treatment options differ.

-

Primary disease often responds to more conservative measures.

-

Some modalities include layered clothing,

woolen gloves and sheepskin mittens (i.e., two layers rather than one),

gloves made from specially insulating fabric, and electrically heated

gloves.

-

-

If there is an occupational exposure suspected, then it should be avoided if possible.

-

For moderate symptoms, in addition to the preventive measures, the athlete may try a topical vasodilator.

-

With more severe symptoms, if

conservative measures are not effective, calcium channel blockers can

be tried, such as nifedipine or diltiazem. -

Recent studies have also shown that

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, may be

effective in reducing the severity and frequency of attacks.

-

There are no specific contraindications

to participation in sports but, depending on the severity, athletes may

need to modify the environment in which they are participating. -

Uncontrolled symptoms despite modifications and medical treatment may necessitate discontinuation of sport.

competition may expose themselves to traveler’s diarrhea. Traveler’s

diarrhea was first described in travelers to Mexico and is now endemic

in many parts of the world. The etiology of most traveler’s diarrhea is

bacterial, but viral and parasitic infections have been implicated.

Potential bacterial pathogens that have been isolated include

enterotoxigenic E. coli (most common), Shigella species, Campylobacter species, Salmonella species, Aeromonas species, Plesiomonas shigelloides, and noncholera Vibrios. Viral etiologies include Norwalk virus, rotavirus, and enteric adenoviruses. Parasitic causes include Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Cyclospora cayetanensis. Most cases of traveler’s diarrhea come from contaminated food and water.

-

Traveler’s diarrhea is often associated with travel to developing and tropical areas.

-

It is defined as the passage of at least

three unformed stools in a 24-hour period, with associated nausea,

vomiting, abdominal pain or cramps, fecal urgency, tenesmus, or the

passage of bloody or mucoid stools in a person who normally resides in

an industrialized region and travels to a developing tropical or

semitropical country. -

This includes illness that develops within the first 7 to 10 days after returning home.

-

A typical course consists of 3 to 10 unformed stools daily for 3 to 5 days.

-

In the presence of the above symptoms, the diagnosis can be confirmed with examination of the stool.

-

If fecal leukocytes are present, a bacterial pathogen is likely.

-

If fecal leukocytes are absent, it does not rule out that a bacterial pathogen may still be present.

-

-

Other diagnostic tests include stool cultures looking for the specific pathogen.

-

Prevention strategies are essential to avoid acquiring traveler’s diarrhea in at-risk regions.

-

Consuming bottled water and carbonated

beverages—while avoiding tap water, ice cubes, and fresh vegetables—are

simple measures that can help prevent an infection. -

Initial treatment should focus on replacement of fluids and electrolytes to prevent dehydration from diarrhea.

-

Most traveler’s diarrhea will respond to antibiotic treatment.

-

As a result of resistance to

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), most travelers will respond to

treatment with the fluoroquinolones. -

First-line therapy can be ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 5 to 7 days.

-

In areas where resistance has been seen, azithromycin has been used effectively in all bacterial pathogens.

-

-

A nonantibiotic treatment includes bismuth subsalicylate, which can reduce the number of unformed stools and decrease symptoms.

-

Loperamide, an antimotility agent, can

also help symptoms by decreasing intestinal motility and enhance the

intestinal absorption of fluids and electrolytes.-

Loperamide should be avoided though in the presence of dysentery, with symptoms such as high fever, chills, and bloody diarrhea.

-

-

Prophylactic treatment should be considered when traveling to high-risk areas.

-

Bismuth subsalicylate in the form of two 262-mg tablets four times a day has been effective in decreasing attacks.

-

-

Self-treatment with loperamide and oral

hydration can be used for onset of mild symptoms and an antibiotic,

such as a fluoroquinolone, can be added when more severe symptoms are

present.

hemoglobin that is lower than the expected range for someone their

gender and age. The correlation between exercise and anemia has sparked

more investigation about this subject. The mean hemoglobin

concentration of the exercising versus the nonexercising population is

lower. The difference is even more notable in the more elite endurance

athletes. Anemia is often misconceived as a disease, opposed to the

result of a physiologic response or aberrancy.

expansion is the most common cause of anemia in the athlete. Dilutional

pseudoanemia should not affect other parameters in a complete blood

cell count (CBC) (mean red cell volume, ferritin) or haptoglobin. It

should not be associated with symptoms. When training ceases, the

hemoglobin should normalize in 3 to 5 days.

been seen in endurance athletes. It is primarily the result of

mechanical trauma but is also linked to exercise intensity.

seen in athletes. In one study, 80% of young female athletes and 30% of

elite male athletes were found to be iron deficient. The causes of iron

deficiency anemia are many. Some of the etiologies include poor

nutrition, exercise-induced hemoglobinuria or hematuria, gastritis, and

hemorrhoids.

-

The diagnosis is made by laboratory

evaluation, which should include CBC, haptoglobin, urinalysis, and iron

studies (iron, ferritin, and total iron-binding capacity). -

If more suspicious and searching for

another possibility, one may also choose to get other studies,

including reticulocyte count, hemoglobin electrophoresis, fecal occult

blood tests, and coagulation profile.

-

Treatment is inevitably to address underlying cause if a true anemia is detected.

-

The treatment may be as simple as diet manipulation or supplementation.

-

Usually, athletes self-preclude if their symptoms do not allow expected performance.

-

There are no guidelines for individual events.

Sickle cell anemia, thalassemias, and clotting disorders are a few of

the important ones to review. These disorders are genetically

inherited, and a complete family history is important in these

situations.

possess the sickle cell gene in either a homozygous (disease-HbS) or

heterozygous state (carrier-HbS). The carriers usually do not have

crises. Homozygous individuals can experience acute chest syndrome and

aplastic crises among other complications.

These are multifactorial anemias characterized by defects in the α-

and/or β-subunit of the hemoglobin tetramer. Hemolysis occurs

chronically in people with thalassemias.

factor deficiencies) have aberrancies in their clotting cascade,

rendering them unable to clot in an organized way. Hemostasis normally

occurs via a series of well-choreographed steps (coagulation cascade).

A vascular response initially helps to form a platelet plug. This

process is followed by the activation of coagulation factors leading to

the stabilization of the platelet plug by fibrin.

-

Blood samples should be ascertained for the above disorders if there is clinical suspicion.

-

Sickle cell and thalassemias need CBC,

peripheral smear, hemoglobin electrophoresis (in some instances), and

reticulocyte count (especially in crisis). -

A haptoglobin level and liver function

tests (bilirubin direct and indirect) can also be done if there is an

acute hemolytic event. Clotting disorders need laboratory evaluation as

well. -

In clotting disorders, PT, PTT, and INR are important, as are CBC and a peripheral smear.

-

Treatment involves addressing the underlying cause.

-

In many instances, careful observation is the only intervention that can be pursued.

-

Hydration is the key preventive measure, especially with heat or outdoor activities.

-

It is recommended that those who are

afflicted with HbS (disease), as well as other coagulopathies, not be

involved in contact sports.P.145-

Most providers recommend against heavy exertion because this could increase oxygen debt and cause crisis.

-

-

High-altitude participation, including flying in unpressurized cabins, is also not favorable for those afflicted.

-

One must use clinical judgment because no specific “exclusion” criteria exist.

-

Participants with thalassemia and HbS (carriers) should not have restrictions but should be monitored.

performance. Blood doping is a scientifically proven illegal means of

enhancing athletic performance. In the past, athletes would donate

blood a few weeks before a competition and then replace this blood

before competition. This process would in turn increase this athlete’s

hemoglobin concentration, hence causing their oxygen-carrying capacity

to increase. This “autologous” type of transfusion is virtually

obsolete after the advent of rHuEpo. Erythropoietin is a genetically

engineered copycat kidney hormone that stimulates the bone marrow to

produce red blood cells. Numerous side effects are known to occur from

blood doping. Some of these documented side effects are pulmonary

embolism, myocardial infarct, and stroke, just to name a few. There

were a few documented deaths in the early 1990s in Dutch cyclists

before erythropoietin was banned.

-

There are very sensitive tests to test

urine via liquid chromatography to detect exogenous erythropoietin and

also other subtle peptides. -

Prevention involves education about possible side effects and avoidance.

-

If detected, the participant is

disqualified because erythropoietin and blood doping are banned in most

competitive endurance sports. -

The IOC banning occurred in 1996, and testing occurred at the Olympic Games in Atlanta 1996.

were reported in the year 2000. Of those injuries, more than 70%

occurred in people under 25 years of age, and two thirds of the

injuries occurred in persons between the ages of 5 and 25. The cause of

these injuries is multifactorial. Some of the factors may include the

number of people involved in athletic activities, the aggressive nature

of play, and at times the lack of supervision. The most common eye

injuries in sports affect the anterior globe. Corneal abrasions account

for 83% of nonperforating anterior globe injuries. Subconjunctival

hemorrhage, foreign bodies, hyphema, retinal detachment, and globe

rupture are a few injuries that can also occur. Subconjunctival

hemorrhage occurs from blunt trauma, as does hyphema and often retinal

detachment.

-

Diagnosis of most of the aforementioned ocular injuries is made by physical diagnosis.

-

An important part to precede the physical examination is the history.

-

Ask about the person’s vision and examine the pupils.

-

If the patient is unable to open the eye, do not force the lid open, because a globe rupture may be present.

-

-

The main complaint with detached retina is visual disturbance.

-

Corneal abrasions can be seen after application of fluorescein stain (Fig. 12-5).

-

If a foreign body is seen during this examination, one may take this opportunity to remove it if it is superficial.

-

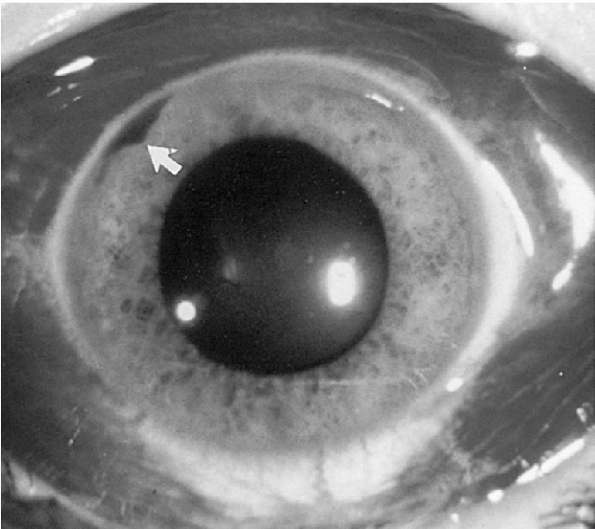

In a subconjunctival hemorrhage, the conjunctiva becomes erythematous and has a bloodshot appearance (Fig. 12-6).

-

Extensive hemorrhage should make one worry about a ruptured globe.

-

A hyphema is when there is blood in the anterior chamber (see Fig. 12-6).

|

|

Figure 12-5

A large, traumatic corneal abrasion stains brightly after topical fluorescein instillation. (From Tasman W, Jaeger E. The Wills Eye Hospital Atlas of Clinical Ophthalmology, 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.) |

|

|

Figure 12-6 Subconjunctival hemorrhage extending for 360 degrees. Note the small hyphema (arrow).

(From Fleisher GR, Ludwig W, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.) |

-

Corneal abrasions

-

Apply topical anesthetic, then apply fluorescein strips to the conjunctival sac.

-

Identify the abraded epithelium, which is the area that is fluorescent green when viewed with a cobalt blue light.

-

Antibiotic should be applied.

-

Mandatory 24-hour follow-up is necessary.

-

Pain and blepharospasm may make it difficult to open the eye.

-

The athlete may not return to play.

-

-

Superficial corneal foreign body

-

Apply topical anesthetic.

-

Remove the foreign body with sterile irrigation solution or a moistened sterile cotton swab.

-

Never use a needle to remove the foreign body.

-

Apply topical antibiotic.

-

Mandatory 24-hour follow-up.

-

If unable to remove the foreign body, do not allow return to play.

-

-

Concealed foreign body

-

Usually located under the eyelid or lower

fornix, as frequently suggested by vertical linear corneal abrasions

that show after fluorescein strip staining. -

Evert upper eyelid and irrigate with sterile irrigation solution or moistened swab.

-

Follow corneal abrasion guidelines if present.

-

If there is no corneal abrasion, the athlete may return to play.

-

Patching is not recommended.

-

-

Hyphema

-

Blood is present in the anterior chamber.

-

Intraocular pressure may increase.

-

The eye should be shielded and immediate referral should be made.

-

No return to play is acceptable.

-

-

Patients with visual complaints (such as

floating bodies and/or papillary defect) and any of the other diagnoses

should be referred to an ophthalmologist for possible retinal issues or

optic neuropathy.

-

Participation should be withheld until proper treatment is implemented and vision returned to baseline.

-

Information about proper eyewear in

various sports arenas should be discussed, because up to 90% of eye

injuries may be avoidable. -

Improper eyewear and protective eyewear are often overlooked.

large percentage (40%) of bony injuries in facial trauma. In children,

play and sports account for a majority of nasal fractures. In a nasal

injury, there are other problems besides fractures that should be

evaluated. A septal hematoma or deformity, as well as epistaxis, can

also occur. A septal hematoma is a blood-filled cavity between the

nasal cartilage and the perichondrium. This area can become infected,

and necrosis can ensue. Epistaxis at times can impair the ability to

perform a thorough examination. The vascular anatomy of the nose

renders it susceptible to bleeds. There is a dense vascular network

that supplies the nose called “Kiesselbach’s area.” This plexus is

responsible for most simple nosebleeds. The bleeding that occurs

secondary to a fracture is usually from the sphenopalatine artery

(posterior) or the anterior ethmoid artery (anterior). Septal hematomas

often occur with nasal trauma and can result in septal deformities.

-

Diagnosing nasal injuries is performed via history and physical examination.

-

An idea of the type of force involved will either broaden or narrow the differential diagnosis.

-

Epistaxis may be the only finding in some nasal fractures.

-

Palpation may uncover crepitus or step-off deformities during the examination.

-

Ecchymosis and edema will usually occur within minutes to an hour after the injury.

-

-

With a nasal speculum and good light, one

should examine the nasal septum, mucosa, floor, and turbinates. Also

check for airway patency.-

Internal examination of the nares will often be obscured by blood or clots.

-

Saline irrigation or removal with cotton-tipped applicators may aid in the examination.

-

One should be able to visualize if a septal hematoma is present.

-

One should also check for clear rhinorrhea.

-

-

The surrounding structures of the nose should be examined as well.

-

Disconjugate extraocular movements give concern for orbital fractures.

-

Tenderness over other facial areas gives

concerns for other fractures, including the zygomatic arch, malar

eminences, and mandible fractures.

-

-

X-rays are often obtained for simple

fractures but may be of limited value for occult or complex fractures

as a result of poor sensitivity and specificity. -

If there are other concerning signs (such as clear rhinorrhea or disconjugate gaze), CT imaging is indicated.

-

Epistaxis should initially be treated with direct pressure for stasis.

-

If stasis becomes an issue, packing can be performed.

-

-

With nasal fractures, if reduction of a gross deformity is required, it should be performed within 5 to 10 days of the injury.

-

If there is no mucosal injury, septal hematoma, or deformity, splinting may be used.

-

-

If there is an open fracture or mucosal

injury, the injured participant’s tetanus status should be ascertained;

infection may possibly occur.-

Appropriate referral should be made.

-

-

Septal hematomas need to be drained because a saddle deformity may result.

-

Immediate needle aspiration under local anesthetic should be done.

-

Referral once again would be optimal.

-

-

Because reinjury (including the

possibility of airway compromise) exists, as well as an increased

chance of rebleeding, one should err on the side of caution and use

good judgment for return to play. -

Generally, return is allowed if homeostasis is obtained and the area can be protected with a facial shield or mask.

-

No set guidelines exist.

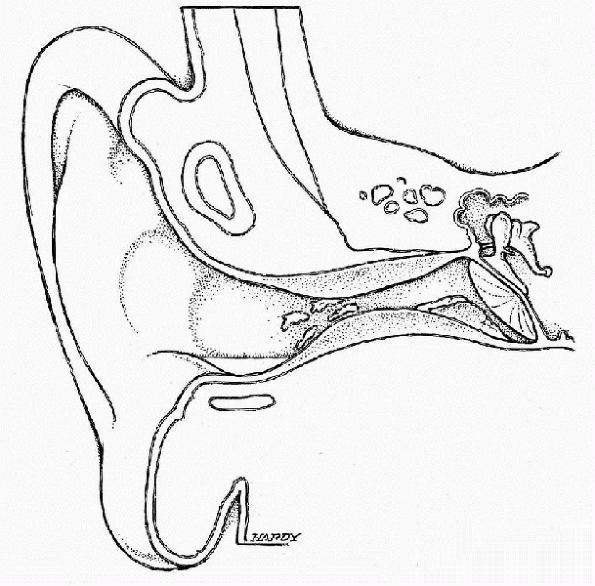

It is caused by a breakdown in the normal skin barrier in the ear

canal, often related to elevated humidity and warmer temperatures. It

is commonly associated with water sports such as swimming or water

polo. Other risk factors are local trauma to the external ear or

maceration of the skin. The common bacteria that normally populate the

healthy external auditory canal are Staphylococcus auricularis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and diphtheroids. When the skin barrier breaks down, infection develops, with the predominate pathogens being Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus.

|

|

Figure 12-7 Illustration of otitis externa (swimmer’s ear). (Courtesy of Neil O. Hardy, Westpoint, CT.)

|

-

Diagnosis is clinical, based on the clinical history and physical examination findings.

-

The most common complaint with OE is pain, often severe, with itching preceding the pain.

-

Patients may also complain of purulent secretions or a feeling of fullness secondary to edema.

-

A history of recent water exposure is usually present.

-

-

On physical examination, the physician should evaluate the external auditory canal for signs of inflammation or infection.

-

Erythema or thick drainage may be seen.

-

There is usually pain on manipulation of the external ear.

-

-

Evaluation of periauricular lymph nodes should also be performed, as enlargement of these nodes may signify an infection.

-

Differential diagnosis needs to include acute otitis media and necrotizing OE.

-

The tympanic membrane needs to be

evaluated, and if it is erythematous and bulging, treatment for acute

otitis media should be considered. -

Necrotizing externa is a malignant rare variant of OE that is caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is associated with systemic invasion.

-

It has primarily been described in elderly adults who have diabetes mellitus.

-

They note severe pain, especially at night, as well as discharge, hearing loss, and a sensation of fullness.

-

They may develop facial nerve palsy.

-

Examination reveals inflammation and granulation tissue at the bony-cartilaginous junction.

-

-

First-line treatment for OE is topical.

-

Choices include 2% acetic acid or a topical antibiotic containing aminoglycoside, polymyxin, or fluoroquinolone.

-

Topical corticosteroids are also effective in combination with a topical antibiotic.

-

Topical or oral analgesics are used for the treatment of pain.

-

There are no specific contraindications to sports participation with OE.

-

Treatment should be initiated to decrease symptoms.

-

Preventative measures may include the use

of earplugs while swimming or prophylactic use of 2% acetic acid to

decrease the amount of moisture in the ear.

ear that represents the most frequent diagnosis when children present

to a physician with a complaint. The most frequent bacterial pathogens

in AOM are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Other, less common bacterial causes are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, enterococcus, group B streptococcus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Viral pathogens include respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza,

influenza, cytomegalovirus, enterovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, herpes

simplex virus, and coronavirus.

-

AOM is often preceded by a recent upper respiratory tract infection.

-

The eustachian tube fails to drain the middle ear effectively and provides a culture medium for bacteria.

-

Once the middle ear becomes infected, patients may complain of ear pain or fever.

-

A history of sick contacts or recent upper respiratory infection symptoms must be addressed.

-

Physical examination should include evaluation of vital signs, including evaluation for the presence of a fever.

-

Characteristic findings on examination include a bulging tympanic membrane with purulent fluid visible in the middle ear (Fig. 12-8).

-

-

Pneumatic otoscopy can also be used to demonstrate decreased mobility of the tympanic membrane, suggestive of middle ear fluid.

-

Diagnosis of AOM can be difficult because there are no good diagnostic tests.

-

Diagnosis relies on the presence of an acute illness and middle purulent ear fluid.

-

Most cases of AOM will resolve

spontaneously without use of antibiotic therapy. Therefore, watchful

waiting is an acceptable approach in managing AOM in the age group of

most athletes. -

Symptomatic treatment with oral fluids to prevent dehydration and analgesics for pain can be used.

-

Despite the high frequency of spontaneous resolution, antibiotics are still frequently prescribed by physicians.

-

Common antibiotics used include

amoxicillin, erythromycin-containing preparations such as azithromycin,

and amoxicillin/clavulanate (for nonresponsive infections).-

Judicious use of antibiotics should be used to prevent creation of resistant organisms.

-

|

|

Figure 12-8

Acute otitis media with bullae formation and fluid visible behind the tympanic membrane. (Courtesy of Alejandro Hoberman, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh.) |

-

In athletes who develop an AOM, there are no specific return-to-play restrictions.

-

Symptoms should guide the athlete’s decision.

-

Participation with a fever ≥38°C should

restrict the athlete from participating as a result of the risk of

developing heat illness.

ear where there is a collection of blood beneath the perichondrial

layer. If untreated, this will progress to become “cauliflower ear.” It

is a common condition seen in wrestlers, boxers, and martial artists

but can also occur in the helmeted athlete and other activities. It

occurs with blunt trauma or repetitive shearing forces to the ear’s

pinna.

-

An auricular hematoma is diagnosed by history and PE.

-

On physical examination, an edematous region at the pinna is palpable and easily seen (Fig. 12-9).

|

|

Figure 12-9

Auricular hematoma. The smooth, discolored mass obscuring the normal contour of the pinna is a hematoma. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.) |

-

No single method has proved better than another for long-term outcomes.

-

One wants to drain the hematoma and place a compression dressing on it to avoid reaccumulation of blood.

-

This can be done with a needle under sterile conditions or via incision.

-

If incised, the sutures should remain in place for up to 14 days.

-

This intervention for long-term outcome is even controversial.

-

-

Silicone splinting has been recommended for a quicker return to play and decreased reoccurrence.

a minimum of 24 hours. On return, they should wear proper protective

gear (i.e., wrestler’s headgear). Some recommend continued compression

dressing for the remainder of the season.

cavity or space when there is failure to equalize a change in

barometric ambient pressure. It often occurs in water sports either

with rapid descent/ascent in self-contained underwater breathing

apparatus (SCUBA). Barotrauma can occur at the middle ear or the inner

ear. Contact at the air-water interface in diving, water-skiing, and

other water activities can cause rupture of the tympanic membrane.

-

Diagnosis is made by history more than physical examination, with the exception of ruptured tympanic membrane.

-

Neurologic symptoms include change in hearing, vertigo, pain and, at times, Bell’s palsy.

-

In inner ear barotrauma, the symptoms may also include emesis, nystagmus, and tinnitus.

-

Antihistamines and analgesia in many cases will suffice.

-

If there in a tympanic rupture, one should consider antibiotics.

-

In a more severe case (as in inner ear

barotraumas, bed rest with head elevation, and stool softeners), one

may also highly consider ENT referral if symptoms are prolonged.

-

Participation is dependent on symptoms.

-

Usually, participants will self-preclude.

-

Athletes with perforated tympanic membrane need to avoid water immersion and swimming until perforation resolves.

throat; and head injuries, skull and mandible fractures do occur. High

velocity or impact is needed for these types of injuries to occur.

with these types of injuries, although they can also occur as an

isolated injury. It is estimated that 35% of all dental injuries are

the result of sports injury. Fifty-six percent of dentoalveolar injury

occurred with other associated injuries. Mandible fracture etiology has

changed over the past two decades. In the past, these types of injuries

were mostly secondary to motor vehicle accidents, violence, and

assaults. Sports injuries have now been steadily rising as an etiology

as per some studies. Cycling, skiing, and hockey—among other

sports—have an increased incidence of mandible fractures.

concurrent bleeding, have good outcomes. There are times that a

depressed fracture may occur. Appropriate field management will be

discussed.

-

History and clinical findings are important in the diagnosis.

-

Gross deformities such as a palpable depressed skull fracture or a mandibular deformity are more easily diagnosed.

-

The subtle findings of malocclusion or cerebrospinal fluid oto/rhinorrhea are also clinical clues pointing toward fractures.

-

Radiologic studies are helpful in these cases.

-

Plain x-rays in suspected mandible

fractures are often diagnostic, whereas findings on plain x-ray are

less useful in suspected skull fractures. -

CT scan is the diagnostic standard if a skull fracture is likely.

-

-

Some dental fractures are difficult to assess where frank avulsions and luxations are not.

-

Skull fractures, if a palpable deformity is evident, need immediate follow-up.

-

If no deformity is evident but suspicion is high, clinical hospital referral is appropriate.

-

-

There are some specific bruising patterns that correlate with certain fractures of the skull.

-

Raccoon eyes and battle signs are two of these patterns that happen a few hours after the trauma.

-

-

Plain radiography is of little use,

whereas CT is more sensitive and specific, especially in determining

concurrent intracerebral injury.

-

Dentoalveolar injuries have a specific protocol for specific injury.

-

Complete avulsion (“knocked out of

socket”) treatment includes rinsing the tooth with saline (do not

scrub), replacing it in the socket, and following up immediately with a

dentist.-

If unable to replant, place tooth in milk or in the buccal vestibule of the athlete with emergent dental follow-up.

-

-

Tooth fracture, where there is no

sensitivity to air, generally allows for return to play that game with

dental follow-up within 24 to 48 hours. -

Severe pain may be associated with a more significant tooth fracture or occult fracture.

-

These athletes should be withheld from playing and have emergent dental follow-up.

-

-

Tooth luxations (partial dislocation) have other protocol depending on if the tooth is extruded, intruded, or laterally luxated.

-

Overall, if there is a possible underlying alveolar fracture, do not try to reduce the tooth.

-

Dental referral is recommended in most situations.

-

-

Many mandible fractures are managed by closed maxillomandibular fixation or occlusal splinting.

-

Skull fractures need appropriate referral and intervention.

evaluation prior to participation. A physician’s responsibility changes

as an on-site medical provider at an athletic event. Providers should

be aware of special situations, especially single organ or structure,

that may be encountered on the playing field.

-

Single- or one-eye blind may be encountered.

-

Acuity of 20/40 is considered to provide good vision.

-

Athletes with less than this level of visual acuity with correction should be considered functionally one-eyed.

-

Because there are numerous protective

devices for the eyes, many athletes can participate in various sports

with knowledge of their inherent dangers. -

Sports have been rated in an eye injury risk classification.

-

-

Players with a single testicle or undescended testicle should wear protective cups.

-

They should also be warned of the increased incidence of testicular cancer in an undescended testicle.

-

No restrictions are given to these participants.

-

-

Athletes with a single kidney, single functioning kidney, or a pelvic kidney have restrictions in sports.

-

Though the incidence is rare, the ability

of the participant to injure his or her only functioning kidney would

render the individual in need of a transplant or lifelong dialysis. -

The recommendation from most health care providers would be to not indulge in contact or collision sports.

-

There are no formal restrictions.

-

If the player decides to play, special recommendations for protective gear, such as a flack jacket, should be encouraged.

-

-

People with diabetes may participate in

any sport, although there is a recommendation against endurance

activity involvement (marathon, triathlon).-

The most important factor is of course glycemic control.

-

If the player has a finger-stick blood

glucose level >250 with ketosis or a finger-stick blood glucose

level >300, then the player should be held out. -

If the glucose level is <100, the athlete should ingest a substance with carbohydrates.

-

The player should also stay ahead of their fluids.

-

Sports classified as high risk for people

with diabetes because of their ability to become hypoglycemic include

SCUBA, rock climbing, and skydiving.

-

BB. New strategies for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of

herpes simplex in contact sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2004;3: 277-283.

Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and the

American Academy of Ophthalmology, EYE. Health and Public Information

Task Force. Protective eye wear for young athletes [joint policy

statement]. Ophthalmology 2004;111: 600-603.

WL Jr, Dightman L, Dworkin MS, et al. Pinning down skin infections:

diagnosis, treatment, and prevention in wrestlers. Physician Sportsmed

1997;25.

infections among competitive sports participants—Colorado, Indiana,

Pennsylvania, and Los Angeles County, 2000-2003. MMWR 2003;52:793-795.

MJ, Maron BJ, Zipes DP. 36th Bethesda Conference: eligibility

recommendation for competitive athletes with cardiovascular

abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1318-1373.

oral health: interventions for preventing dental caries, oral and

pharyngeal cancers, and sports-related craniofacial injuries. MMWR

2001;50(RR 21):1-13.

Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The National Heart,

Lung, and Blood Institute National Institute of Health. May 2003;3:5233.