Principles of Arthroscopic Surgery

advance at a rapid pace. Arthroscopic techniques have significantly

changed the approach to the diagnosis and treatment of orthopaedic

joint pathologies. A high degree of clinical accuracy, combined with

low morbidity, has encouraged the use of arthroscopy to assist in

diagnosis, to determine prognosis, and often to provide treatment. Two

critical aspects of arthroscopic surgery are the correct placement of

arthroscopic portals and the avoidance of complications. During

arthroscopy of any joint, accurate placement of the portals is

essential to adequately accomplish the intended goal of the procedure

without complications. Fortunately, complications during or after

arthroscopy are infrequent and are usually minor. Most complications

can be prevented with careful and thorough preoperative and

intraoperative planning and attention to the details of arthroscopic

techniques.

illumination and distention of the joint, as well as accurate placement

of the portals. With improper portal position, it may be difficult to

obtain adequate visualization of the intra-articular anatomy and to

maneuver the instruments to all locations within the joint. Improperly

placed portals can cause the surgeon to force the arthroscope or

instrument into position and can result in articular injury, instrument

damage or breakage, and/or other problems. Accurate portal placement

can be obtained by a thorough understanding of the anatomy.

Specifically, the surgeon must know where the medial and lateral joint

lines are, the border of the patella and patella tendon, and the

posterior contours of the medial and lateral femoral condyles. These

areas can be marked with a skin-marking pen before joint distention.

-

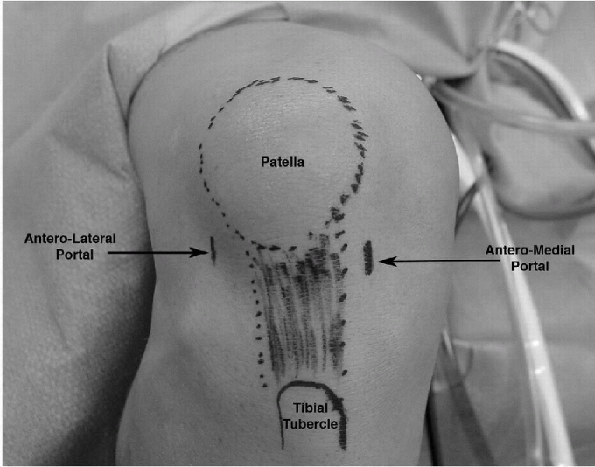

The anterolateral and anteromedial portals are made with the knee in flexion.

-

Vertical or horizontal incisions are

placed adjacent to the patella tendon and approximately 1 cm above the

joint line, typically just below the inferior pole of the patella (Fig. 11-1). -

The scalpel is used to incise the skin

only, and the joint capsule is penetrated with a blunt-tipped

obturator, and aimed toward the notch to avoid articular cartilage

injury. -

If the portal is placed too close to the joint line, the anterior horn of the meniscus can be damaged.P.127

-

Also, the arthroscope can pass either

through or beneath the anterior horn of the meniscus, resulting in

damage to the anterior horn or difficulty in maneuvering the

arthroscope within the joint.

-

-

If the portal is placed too superior to

the joint line, it prevents the view of the posterior horns of the

menisci and other posterior structure.-

An arthroscope placed immediately

adjacent to the edge of the patellar tendon can go through the fat pad,

causing difficulty in viewing and maneuvering the arthroscope in the

joint.

-

-

With the use of a 4-mm diameter,

30-degree oblique arthroscope through an appropriately placed

anterolateral portal, the structures within the knee joint can be

visualized.

|

|

Figure 11-1 Knee landmarks and portal locations.

|

-

The posteromedial portal is positioned in

a soft spot formed by the posteromedial edge of the femoral condyle and

the posteromedial edge of the tibia.-

This location can be palpated with the knee flexed to 90 degrees.

-

With the knee fully distended and flexed to 90 degrees, this portion of the compartment will balloon out.

-

-

The location of this portal is

approximately 1 cm above the posteromedial joint line and approximately

1 cm posterior to the posteromedial margin of the femoral condyle. -

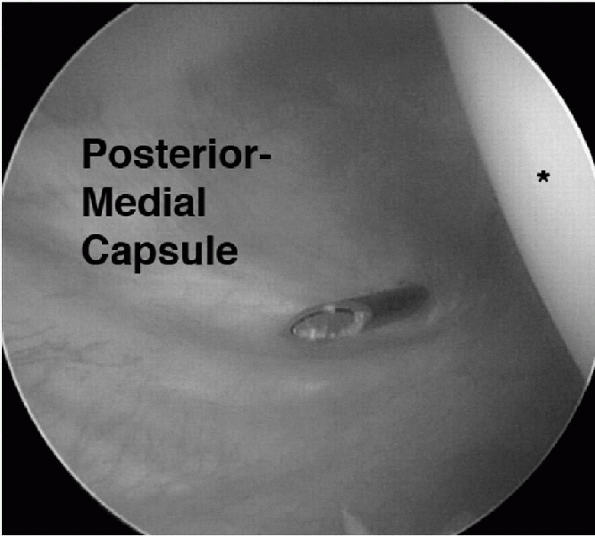

To aid with precise location of this

portal, the arthroscope can be inserted through the notch along the

lateral portion of the medial femoral condyle (modified Gillquist view)

and into the posterior aspect of the knee to visualize the placement of

a spinal needle in the posteromedial portal (Fig. 11-2). -

The arthroscope’s light illuminates the

area around the portal, allowing visualization of the saphenous vein,

which should be avoided when making this portal. -

This portal is always established with a blunt-tipped obturator.

|

|

Figure 11-2

Arthroscopic view from the anterolateral portal showing insertion of a spinal needle, localizing the best position for establishing the posteromedial portal. Asterisk indicates the posterior medial femoral condyle. |

-

The superolateral portal is typically used for inflow or outflow.

-

It can also be useful for viewing and

accessing the dynamics of the patellofemoral articulation and can be

helpful for excising a medial plica. -

This portal is located just lateral to

the quadriceps tendon and about 2 to 3 cm superior to the superolateral

corner of the patella. -

Viewing the patellofemoral joint from

this portal using a 70-degree arthroscope allows evaluation of patellar

tracking, patellar congruity, and lateral overhang of the patella as

the knee is inspected through a range of motion.

-

The posterolateral portal is made with the knee flexed about 90 degrees and the joint maximally distended.

-

The posterolateral portal is about 2 cm

above the posterolateral joint line at the posterior edge of the

iliotibial band and the anterior edge of the biceps femoris tendon. -

Care must be taken not to place the portal too far posterior because the common peroneal nerve can be injured.

-

A small skin incision is made, and the posterior edge of the lateral femoral condyle is palpated with a blunt trocar.

-

By slipping off the posterior condyle,

directing it slightly inferiorly, the sheath will be directed into the

posterolateral compartment. -

Be cautious not to damage the articular surface of the posterior femoral condyle with the trocar.

-

Care must be taken not to plunge in, because the popliteal space could be inadvertently entered.

-

The arthroscope may be positioned into

the posterolateral joint via the anteromedial portal (similar to the

Gillquist view), and a spinal needle can again be used to localize the

appropriate position.

-

The optional midpatellar portal is used

to improve the viewing of the anterior compartment structures, the

lateral meniscocapsular structures, and the popliteus tunnel. -

This portal is also used to minimize crowding with the arthroscope during procedures requiring several accessory instruments.

-

These portals are located just off the medial and lateral edges of the midpatella at the broadest portion of the patella.

-

The accessory far medial and lateral portals can be used for bringing accessory instruments into the knee.

-

They are located 2 to 3 cm medial or lateral to the standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals.

-

Medially, these portals are near the

anterior edge of the tibial collateral ligament; laterally, they should

be well anterior to the fibular collateral ligament and popliteus

tendon. -

One technique is to insert a spinal

needle through the skin and capsule and into the compartment under

direct vision with the arthroscope. -

The needle can be adjusted and directed

to its desired location to help ensure the instrument will be able to

reach this location easily. -

There can be increased risk of damage to

the meniscus, collateral ligaments, and the articular surface of the

femoral condyle with these portals, and extreme care should be

exercised when making them.

-

The transpatellar tendon portal is

located approximately 1 cm inferior to the inferior pole of the patella

through the patellar tendon and is angulated to pass above the fat pad. -

This portal incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous tissue with the knee flexed 90 degrees.

-

The tendon is then split with the sharp trocar.

-

The knee is then extended to 45 degrees, and the sheath and obturator are aimed toward the superomedial compartment.

-

This helps prevent passing the arthroscope into the fat pad.

-

-

This portal can be used for central viewing or grasping.

-

This portal is not recommended secondary to the risk of injuring the patella tendon and potential for anterior knee pain.

report on 395,566 arthroscopies—375,069 of which were knee

arthroscopies—from the Committee on Complications of the Arthroscopy

Association of North America. The overall complication rate was 0.56%.

In the knee, there were 239 infections, 12 vascular injuries, 683 cases

of thrombophlebitis, and 190 cases of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. The

complication rate in meniscal repair was 2.4%, including 30 saphenous

nerve injuries, 6 peroneal nerve injuries, 22 infections, 3 vascular

injuries, and 4 cases of thrombophlebitis. With anterior cruciate

ligament procedures, the complication rate was 1.8%, including 7 stiff

knees, 1 infection, 2 neurological injuries, and 12 loose or poorly

placed staples.

prospective study of complications from the Arthroscopy Association of

North America. In this series of 8,741 knee arthroscopies, the overall

complication rate was 1.8%. Sixty-five percent of the complications

were hemarthrosis. The complication rate for meniscal repair had

decreased to 1.29%. The complication rate for medial meniscectomy was

1.78%. Only one neurological injury was recorded, a saphenous nerve

injury during a medial meniscal repair. The complication rate for

anterior cruciate ligament surgery was only 2%, and no neurological or

vascular injuries were reported.

arthroscopy occur at a rate similar to that reported by Small.

Complications may increase with the difficulty and length of the case.

Saphenous and peroneal nerve injuries are still being reported with

arthroscopic meniscal repairs. However, with all inside meniscal repair

techniques, the incidence may decrease. The incidence of arthrofibrosis

associated with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is increased

when meniscal repair is performed concurrently. Likewise, the incidence

of infection associated with anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions

is slightly increased when the reconstruction is performed in

conjunction with meniscal repair. The reasons can probably be

attributed to the additional exposure, surgical time, and potential for

joint contamination during the passing and retrieving of needles.

proper sterilization techniques, handling of the graft, and appropriate

preparation and draping—can help to prevent postoperative infections.

When a postoperative knee infection occurs, urgent and thorough

arthroscopic irrigation and debridement are indicated with repeat

irrigation and debridement at 48 to 72 hours if the patient is still

symptomatic. Anterior cruciate ligament grafts can be salvaged if no

extensive deterioration of the graft is present. The appropriate

intravenous antibiotics generally are prescribed for 2 to 3 weeks,

followed by oral antibiotics to complete a 6-week course of antibiotic

treatment.

meniscal repairs before regaining muscular tone and motion is

associated with arthrofibrosis. Allowing the patient to regain motion

before surgery greatly decreases the incidence of postoperative

stiffness and arthrofibrosis.

condition that possibly could be decreased by better patient selection,

decreased operating time, and early physical therapy. The best way to

help minimize any complication is proper patient selection, through

preoperative evaluation and operative plan, meticulous and skilled

surgical technique, and close patient follow-up.

a diagnostic and therapeutic tool. The advantages of arthroscopic

versus open procedures include less invasive surgery, muscle

preservation, smaller incisions, improved visualization and access, and

quicker rehabilitation.

-

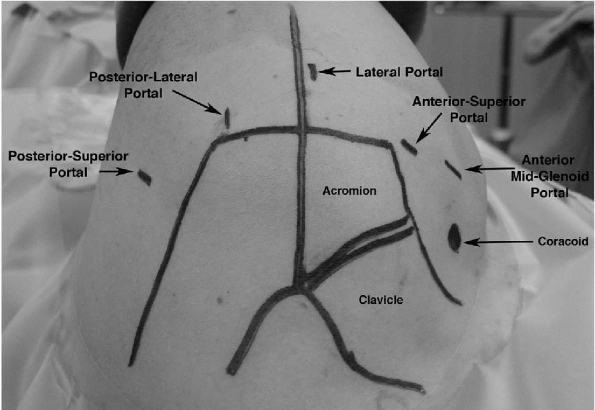

Routine diagnostic arthroscopy is usually carried out through an anterior and a posterior portal (Fig. 11-3).

-

Additional portals are used for special applications.

-

The posterior portal insertion point is chosen after palpating the posterior shoulder anatomy and balloting the humeral head.

-

The exact position is dependent on the thickness of the soft tissue and bony anatomy.

-

In the average-sized individual, the portal is approximately 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to the posterior lateral acromion.

-

For larger patients, the portal is more inferior and medial.

-

-

Make a small incision through the skin without piercing the muscle or capsule.

-

Insert the arthroscope with a tapered-tip

obturator through the muscle until the posterior head is palpated,

while the opposite hand palpates the anterior shoulder joint. -

Balloting the head back and forth helps establish the position of the joint line.

-

Direct the cannula medial to slide off the humeral head to feel the step-off between the head and the glenoid.

-

Finally, insert the cannula through the posterior capsule into the joint (usually feeling a definitive pop).

-

A common error is inserting the cannula too lateral or proximal.

-

|

|

Figure 11-3 Shoulder landmarks and portal locations.

|

-

The anterior portal should be created before performing the diagnostic examination.

-

It is necessary for outflow and to palpate the anatomy.

-

-

The ideal location can only be determined after visualizing the anterior anatomy.

-

Note the condition of the superior labrum and anterior ligaments before determining which anterior portal to make.

-

If anterior reconstruction or superior

labrum, anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion require repair, a high

anterior-superior portal should be made.-

This helps improve visualization of the anterior labral anatomy and allows adequate room for an anterior mid-glenoid portal.

-

-

The anterior-superior portal can be made with an outside in technique.

-

Insert a spinal needle into the skin 1 cm

off the anterior lateral corner of the acromion into the joint through

the rotator interval, just anterior to the biceps tendon. -

Angle the needle to approach the anterior anchor point of the biceps tendon.

-

Make an incision at the needle puncture sight and insert a cannula with a tapered tip obturator.

-

When doing diagnostic arthroscopy and no

SLAP repair or anterior reconstruction is planned, a standard anterior

midglenoid portal can be established. -

To create this portal, an inside-out technique may be used.

-

Pass the tip of the arthroscope into the anterior triangle between the biceps and subscapularis tendons.

-

Then angle the scope a few degrees superiorly and laterally, and hold it against the anterior capsule.

-

Remove the scope, insert a taper-tipped

guide rod (Wissinger rod) into the cannula, puncture the anterior

capsule, and tent the skin. -

Make a small incision adjacent to the

guide rod tip (it should be approximately 2 cm inferior and 1 cm medial

to the anterior lateral edge of the acromion). -

Pass the guide rod out of the incision and pass a cannula over the rod and insert it into the joint.

-

Outflow can be connected to the cannula,

the scope can be inserted into the posterior-superior portal, and the

diagnostic arthroscopy can be performed.

-

The subacromial bursa diagnostic

examination is performed through the already established

posterior-superior portal and the anterior-superior portal. -

Using the posterior portal incision, a cannula with a tapered tip obturator can be directed into the bursal space.

-

This can be achieved by sliding the cannula between the acromion and rotator cuff.

-

It can then be positioned under the anterior-lateral portion of the acromion.

-

-

Next, a Wissinger rod can be placed

through the cannula and passed underneath the coracoacromial ligament

and continued out the anterior-superior portal incision. -

A cannula can then be placed over the rod and slid into the bursa.

-

In addition, a third bursal portal, the lateral acromial portal, is helpful when working in the subacromial space.

-

The portal is made approximately 3 cm off of the lateral border of the acromion.

-

The anterior-posterior position of this portal is critical when performing an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

-

To ensure correct position of your

portal, a spinal needle should first be inserted into the bursa to help

locate the correct position. -

An incision is made where the needle was removed and a cannula is inserted into the bursa.

-

A standard reference point is a line

drawn perpendicular to the lateral margin of the acromion in line with

the posterior aspect of the acromioclavicular joint.

-

An additional portal, preferred by some

surgeons, is the supraspinatus (Neviaser) portal that is used for

inflow or for visualization of the anterior glenoid. -

This portal is placed in the corner of the supraspinatus fossa and oriented slightly anterior and lateral.

-

It should also be placed with the arm

adducted and the trocar angled posteriorly to avoid injury to the

tendinous portion of the rotator cuff.

performed by experienced arthroscopic shoulder surgeons are uncommon.

Portal placement and maneuvering in the shoulder can be more difficult

than the knee as a result of the thickness of the muscles surrounding

the shoulder. There are greater chances for complications as the

procedures become more complex.

and the shoulder is no different. Excessive traction on the shoulder or

improper positioning can lead to transient or permanent nerve injury.

Reports have indicated transient paresthesia rates as high as 30% when

performing shoulder arthroscopy with traction. Anterior portal

placement risks neurovascular injury if the portal is placed too medial

or inferior. Posterior portal placement risks injury to the axillary

nerve if placed too inferior or lateral and risks injury to the

suprascapular nerve if placed too medial.

procedure, the incidence with shoulder arthroscopy is extremely low.

Limited exposure, the rich blood supply, and the irrigation solution

minimize the chances for infection. Sterile technique is critical in

infection prevention, and this can be accomplished through careful

preparation, appropriate draping, and meticulous surgical technique.

of the limited incisions, the rich vascularity about the joint, and the

dilutional effect of the irrigating solution. However, infection can

occur with violations of sterile technique.

successful diagnostic and therapeutic ankle arthroscopy. Improperly

placed portals can make diagnosis and treatment extremely difficult. A

thorough understanding of ankle anatomy is critical to avoid

complications.

-

The anteromedial and anterolateral portals are the primary anterior portals used in ankle arthroscopy.

-

The placement of the anteromedial portal is just medial to the anterior tibialis tendon at the joint line.

-

At this location, there is a premalleolar depression that often bulges in the presence of an effusion.

-

The appropriate position can be determined by first placing a 22-gauge needle at the anticipated position.

-

-

When confirmed, the portal is established

by making a skin incision superficially and then bluntly spreading

through the soft tissue with a mosquito clamp. -

A blunt-tipped obturator with a small diameter cannula is then advanced into the joint.

-

Care must be taken to avoid injuring the

saphenous vein and nerve as they cross the ankle joint on the anterior

aspect of the medial malleolus.-

The anterolateral portal is placed just lateral to the peroneus tertius tendon at or slightly proximal to the joint line.

-

A branch of the superficial peroneal

nerve, the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve, passes over the

inferior extensor retinaculum, crosses the common extensor tendons of

the fourth and fifth digits, and runs toward the third metatarsal space

before dividing into the dorsal digital branches. -

The other branch of the superficial peroneal nerve, the medial dorsal cutaneous nerve, passes over the common extensor tendons.

-

It parallels the extensor hallucis longus

and then divides into three dorsal digital branches distal to the

inferior extensor retinaculum. -

These nerve branches need to be avoided during portal placement.

-

-

An additional anterior portal is the anterocentral portal.

-

It may be developed between the tendons of the extensor digitorum communis at the joint line.

-

The portal is placed between the tendons

to help decrease risk of injuring the dorsalis pedis artery, branches

of the deep peroneal nerve, and medial branches of the superficial

peroneal nerve. -

The dorsalis pedis artery and the deep

peroneal nerve run deep in the interval between the extensor hallucis

longus and the extensor digitorum communis tendons. -

In the past, this portal has been used to

allow easier passage of instruments and the arthroscope from the

anterior and posterior compartments.

-

-

However, the use of this portal is strongly discouraged because of the high potential for complications.

-

Anterior accessory portals can be useful while excising soft tissue or bony lesions in the medial and lateral gutters.

-

The anterolateral and anteromedial accessory portals are commonly used.

-

The accessory anteromedial portal is

established 0.5 to 1 cm inferior and 1 cm anterior to the anterior

border of the medial malleolus.-

This portal is particularly helpful for

removing ossicles inherent to the deep deltoid ligament while viewing

from the standard anteromedial portal.

-

-

The accessory anterolateral portal is

established 1 cm anterior to and just distal to the tip of the anterior

border of the lateral malleolus, near the anterior talofibular ligament.-

This portal is useful for removing ossicles and probing the anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments.

-

-

Posterior portals may be established posteromedial, posterolateral, or trans-Achilles.

-

The posterolateral portal, the most

commonly used and the safest, is placed just lateral to the Achilles

tendon and 1.0 to 1.5 cm proximal to the tip of the fibula.-

There are branches of the sural nerve and the small saphenous vein that must be avoided when establishing this portal.

-

-

The trans-Achilles portal is made at the

same level as the posterolateral, but through the central portion of

the Achilles tendon.-

The portal was originally designed to

allow a posterior two-portal technique, while avoiding injury to the

neurovascular structures medial to the tendon. -

This portal has been discouraged because

it does not allow easy mobility of the arthroscope and instruments and

may lead to increased morbidity of the Achilles tendon.

-

-

The posteromedial portal is established just medial to the Achilles tendon at the level of the joint.

-

The posterior tibial artery, tibial nerve, flexor hallucis longus tendon, and flexor digitorum longus tendon must be avoided.

-

Also, the calcaneal nerve and its

branches divide from the tibial nerve proximal to the ankle joint and

run in an interval between the tibial nerve and the Achilles tendon. -

This portal is also discouraged because of the high potential for serious complications.

-

-

The accessory posterolateral portal is

established 1 to 1.5 cm lateral to the standard posterolateral portal

and at the same level or slightly higher. -

Extreme caution must be used to avoid injury to the peroneal artery, small saphenous vein, and sural nerve.

-

This portal is useful for removing

posterior loose bodies and for debridement and drilling of very

posterior osteochondral lesions of the talus.

-

Transmalleolar portals are used to establish better access to the osteochondral lesions of the talar dome.

-

These portals are particularly useful for

drilling Kirschner wires through the tibia or fibula into the talar

dome under arthroscopic visualization. -

It can also be helpful for bone grafting certain osteochondral lesions of the talus.

-

-

Transtalar portals can be used to drill or bone graft osteochondral lesions of the talus.

advances. Newer techniques continue to develop as equipment and

instruments improve. As the number of arthroscopic procedures has

increased and more demanding procedures have been developed, the

opportunity for potential complications has also increased. The

reported rates are significant and emphasize that extreme caution must

be taken when performing ankle arthroscopy.

injuries and infections. Other reported complications include synovial

fistulae, adhesions, fractures, instrument breakage, and reflex

sympathetic dystrophy. Most complications associated with ankle

arthroscopy are neurologic. Neurovascular injuries can be caused by

incorrect portal placement, prolonged or inappropriate distraction, or

excessive tourniquet time. This usually involves a temporary

paresthesia of the superficial nerves but can be associated with

permanent paresthesia or paresis. Painful neuromas can also occur from

nerves injured during surgery. The anteromedial portal is associated

with injury to the greater saphenous vein or saphenous nerve. The

anterocentral portal is not recommended because of the high risk of

injuring the dorsalis pedis artery and deep peroneal nerve. The

anterolateral portal is associated with significant risk to the

superficial peroneal nerve. This is the most common nerve injured.

Preoperatively, it is critical to mark out the path of the nerve and

its branches to help avoid injury. Unfortunately, in some patients,

particularly those who are obese, the nerve may not be seen directly or

through transillumination. To help minimize potential for nerve damage,

incisions should be made vertically and only through the skin, followed

by careful blunt spreading of the subcutaneous tissue before

penetrating the capsule. The posterolateral portal places the lesser

saphenous vein and sural nerve at risk. The posteromedial portal should

not be used due to the high risk of injury to the neurovascular bundle.

If paresthesias or pain develop postoperatively, this should be

carefully examined and documented. The patient should be informed of

the findings and followed carefully. A positive Tinel’s sign over a

portal site may indicate a neurapraxia or neuroma formation.

to improve visualization with a bloodless field. The complications

associated with tourniquet use include paresthesias, paresis, thigh

pain, and perhaps thrombophlebitis. Proper application, adequate

padding, low pressures, and keeping tourniquet times as low as possible

can minimize problems related to tourniquet use.

|

|

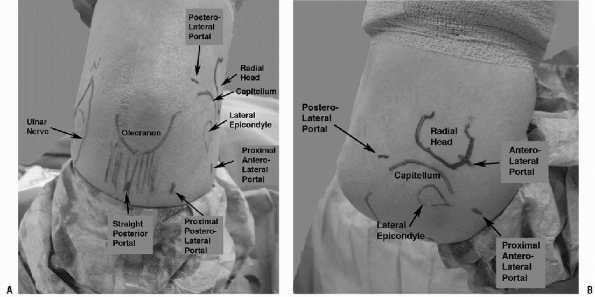

Figure 11-4 Elbow landmarks and portal locations. A: Lateral. B: Posterior.

|

patient selection, a clear understanding of ankle anatomy, and

meticulous surgical technique (especially with regard to portal

placement and the use of blunt dissection down to the capsule).

Assurance of clear vision by maintaining good fluid flow without

overdistention, noninvasive traction, and the use of a small-joint

(2.7-mm) scope and instruments help prevent intra-articular surgical

damage.

advancement in the treatment of elbow disorders. Although useful both

for diagnosis and treatment, elbow arthroscopy can be demanding. With

the proximity to the major neurovascular structures about the elbow,

there is potential for injury, and a thorough understanding of anatomy

is required.

-

The anterolateral portal, usually the standard diagnostic portal, typically is the first established after elbow distention (Fig. 11-4).

-

Anterolateral portals may include the distal anterolateral portal approximately 2 to 3 cm distal and 1

P.133cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle, the midanterolateral portal just

proximal and approximately 1 cm anterior to the palpable

radiocapitellar joint, and the proximal anterolateral portal 2 cm

proximal and 1 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle.

-

-

The proximal portal is significantly farther from the radial nerve than other anterolateral portal sites.

-

This portal allows for an excellent view

of the anterior radiohumeral and ulnohumeral joints, as well as the

anterior capsular margin. -

The elbow is kept flexed during trocar

insertion because extension brings the radial nerve closer to the

joint, placing it more at risk. -

A superficial skin incision should be

made carefully, avoiding deep penetration to protect the lateral and

posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerves. -

Next, a hemostat is used to spread down to the capsule before entering the joint with a blunt trocar.

-

-

The anteromedial portal is placed approximately 2 cm anterior and 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle.

-

This portal can be established using an outside in technique with a spinal needle for localization.

-

The elbow should be flexed to 90 degrees as the portal is established.

-

The median nerve is approximately 1 to 2 cm anterior and lateral to this portal.

-

-

The proximal anteromedial portal is

located approximately 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and

immediately anterior to the intermuscular septum.-

When making this portal, ensure the

position of the intermuscular septum is clearly demarcated, then make a

small portal incision, followed by blunt dissection. -

The trocar is inserted over the anterior surface of the humerus aiming for the radial head.

-

Contact should be maintained with the anterior humerus at all times to reduce risk to the neurovascular structures.

-

This portal allows visualization of the

anterior elbow, including the anterior joint capsule, medial condyle,

coronoid process, trochlea, capitellum, and the radial head. -

The radial head is best visualized from the proximal anteromedial portal.

-

The nerves at risk with this portal

include the ulnar nerve, medial brachial cutaneous, medial antebrachial

cutaneous, median nerve, and brachial artery.

-

-

The posterolateral portal is located in

the center of the anconeus triangle bordered by the radial head,

lateral epicondyle, and the tip of the olecranon.-

This portal can be used to visualize the posterior elbow structures, including the olecranon fossa.

-

The use of a 2.7-mm, 70-degree scope facilitates visualization of the radiocapitellar joint.

-

This portal allows debridement of the capitellum.

-

-

The straight posterior portal is placed 3

cm posterior to the olecranon tip and approximately 2 cm medial to the

posterolateral portal.-

It can be used as a second posterior portal if needed.

-

If the portal is placed too far medial, the ulnar nerve is at risk.

-

The portal can be established under

direct vision; appropriate position of the portal can be confirmed by

placement of a spinal needle. -

In stiff elbows, the direct posterior

portal can sometimes be more easily established than the posterolateral

portal, and the use of a 2.7-mm arthroscope can make visualization of

the posterior compartment easier.

-

in which high attention to detail is critical to help prevent

complications. Temporary or minor complications following elbow

arthroscopy are not rare. In a review of 473 consecutive elbow

arthroscopies by Kelly et al., complications

occurred in 11%. The reported prevalence of neurologic complications

after elbow arthroscopy has ranged from 0% to 14%. In this study, there

were no permanent neurologic injuries, whereas 10 of the 473 (2.5%)

patients did suffer transient nerve palsies. The nerve-to-portal

distances increase with joint distension although the nerve does not

move further away from the capsule. Also, capsular distension is often

difficult in elbows with contractures.

result from compression, local anesthetic, direct trauma, prolonged

tourniquet compression, and/or forearm compression from wrapping too

tight. When making incisions, cutting only through the skin and

dragging the skin rather than making a stab, can help protect the

superficial nerves.

major nerves have been reported. The anterolateral and the anteromedial

portals are the most likely to be associated with nerve injury due to

the closeness of the radial, posterior interosseous, ulnar, and median

nerves. The distances between the nerves and the portals can be

increased substantially by flexing the elbow to 90 degrees and

distending the joint with fluid. With distention of the joint using 15

to 25 mL of fluid, the nerves can be displaced away from the portals,

but the average intracapsular capacity of a stiff elbow is only about 6

mL. Therefore, in stiff elbows, the capsule cannot be distended away

from the instruments.

one must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the elbow and

surrounding neurovascular structures, the effects of joint distention,

and correct portal placement. In addition, recognition of the

procedures that place specific nerves at risk, and excellent

arthroscopic skills are also crucial. In conclusion, two critical

aspects of arthroscopic surgery are: the correct placement of

arthroscopic portals and the avoidance of complications. During

arthroscopy of any joint, accurate placement of the portals is

essential to adequately accomplish the intended goal of the procedure,

and to do so without complications.

Fortunately,

most can be prevented with careful and thorough preoperative and

intraoperative planning and exquisite attention to detail.

NC. Complications in arthroscopy: the knee and other joints. Committee

on Complications of the Arthroscopy Association of North America.

Arthroscopy 1986;2:253-258.