Chondroblastoma

Editors: Frassica, Frank J.; Sponseller, Paul D.; Wilckens, John H.

Title: 5-Minute Orthopaedic Consult, 2nd Edition

Copyright ©2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Chondroblastoma

Chondroblastoma

Constantine A. Demetracopoulos BS

Frank J. Frassica MD

Description

-

A benign tumor of cartilaginous origin with a predilection for the epiphysis in skeletally immature patients

-

Generally found in the epiphyses of long bones.

-

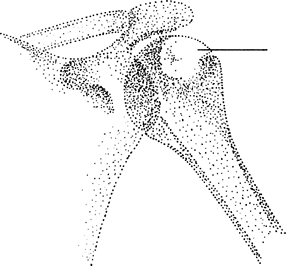

The humerus is most commonly affected, followed by the tibia and femur (1) (Fig. 1-1).

-

-

Synonyms: Codman tumor; Epiphyseal chondromatous giant cell tumor

Epidemiology

A slight male predominance (2:1) is noted (2).

Incidence

-

This tumor is rare.

-

In the largest series, chondroblastoma accounted for 1% of all skeletal neoplasms (3).

Risk Factors

None known

Genetics

No known genetic component exists.

Etiology

-

The pathogenesis is unknown.

-

Most authors agree that the neoplastic cells arise from “cartilage-forming matrix cells” or chondroblasts.

-

The tumor may be related to chondromyxoid fibroma.

Associated Conditions

Aneurysmal bone cyst

|

|

Fig. 1. Chondroblastoma is a lucent lesion in the immature epiphysis, most often the proximal humerus.

|

Signs and Symptoms

-

Patients usually complain of mild to moderate chronic pain, often months to years in duration.

-

Stiffness and effusion of the adjacent joint also are common.

-

Local swelling is uncommon.

Physical Exam

-

The adjacent joint may have an effusion and decreased ROM.

-

A soft-tissue mass is uncommon.

-

Joint tenderness is unusual.

Tests

Lab

-

Tests are not helpful.

-

All blood tests are within normal limits, including the ESR.

Imaging

-

Radiography:

-

The radiographic appearance is that of a lytic lesion in the epiphysis with a thin sclerotic rim.

-

The sclerotic rim indicates the benign nature of the lesion.

-

It may expand or deform the bone.

-

Occasionally, punctate calcifications may be seen.

-

-

The patient’s history and plain radiographs usually are sufficient for making the diagnosis.

-

-

MRI:

-

May be used if history and radiography are not definitive

-

The boundary of the lesion on MRI scans should be distinct.

-

Pathological Findings

-

The diagnosis requires the presence of chondroblasts on microscopic section.

-

Chondroblasts are small, round or polygonal cells with round or oval nuclei.

-

Cells are described as looking “plump” or like fried eggs.

-

A lattice of calcification extends between the cells (chicken wire) (1).

-

-

Interspersed giant cells are a common feature and may lead to confusion with giant cell tumor.

-

Areas of aneurysmal bone cyst degeneration also may be present.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Enchondroma

-

Giant cell tumor

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Fibrous dysplasia

General Measures

-

Surgical excision is recommended to prevent progressive growth of the lesion with destruction of the epiphysis.

-

Bone grafting is needed.

-

Surgery is sometimes technically demanding because of the need to preserve or reconstruct the nearby joint surface.

Activity

No restrictions on activity are necessary because pathologic fracture is not a problem.

P.71

Special Therapy

Physical Therapy

Therapy may be used to regain ROM and strength after surgery.

Surgery

-

Because the tumor is considered benign, local measures suffice.

-

Surgery generally involves curettage and bone grafting.

Prognosis

-

The recurrence rate with chondroblastoma alone is 20% at 3 years (3).

-

If the tumor has an aneurysmal component, the risk of recurrence is higher (3).

Complications

-

Recurrence

-

Joint stiffness

Patient Monitoring

-

Follow-up care is necessary because recurrence is common.

-

Radiographs should be repeated every 6–12 months after excision for ~2 years.

References

1. McCarthy

EF, Frassica FJ. Primary bone tumors. In: Pathology of Bone and Joint

Disorders: With Clinical and Radiographic Correlation. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders Co, 1998:195–275.

EF, Frassica FJ. Primary bone tumors. In: Pathology of Bone and Joint

Disorders: With Clinical and Radiographic Correlation. Philadelphia: WB

Saunders Co, 1998:195–275.

2. Spjut

HJ, Dorfman HD, Fechner RE, et al. Tumors of cartilaginous origin. In:

Tumors of Bone and Cartilage. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of

Pathology, 1971:33–116.

HJ, Dorfman HD, Fechner RE, et al. Tumors of cartilaginous origin. In:

Tumors of Bone and Cartilage. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of

Pathology, 1971:33–116.

3. Huvos

AG. Chondroblastoma and clear-cell chondrosarcoma. In: Bone Tumors:

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders

Co., 1991:295–318.

AG. Chondroblastoma and clear-cell chondrosarcoma. In: Bone Tumors:

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders

Co., 1991:295–318.

Additional Reading

Masui F, Ushigome S, Kamitani K, et al. Chondroblastoma: a study of 11 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:869–874.

Ramappa AJ, Lee FY, Tang P, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone. J Bone Joint Surg 2000;82A:1140–1145.

Suneja

R, Grimer RJ, Belthur M, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone: long-term

results and functional outcome after intralesional curettage. J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87B:974–978.

R, Grimer RJ, Belthur M, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone: long-term

results and functional outcome after intralesional curettage. J Bone Joint Surg 2005;87B:974–978.

Codes

ICD9-CM

213.4 Chondroblastoma

Patient Teaching

-

Patients should be counseled that the lesion is benign and rarely metastasizes (<2%).

-

However, if the tumor is not removed,

local morbidity may occur because of progressive enlargement of the

involved epiphysis and destruction of the joint.

FAQ

Q: Is chemotherapy or radiation therapy needed for chondroblastoma?

A: Chondroblastoma is a benign bone tumor so there is no need for chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Q: Is there any risk of getting a viral disease or hepatitis after curettage and bone grafting for a chondroblastoma?

A:

In general, no risk exists. The graft materials are very safe in that

all the cells and nonbone proteins are removed. The exception is

fresh-frozen grafts, which have the same risk of viral transmission as

a blood transfusion (~1 in 500,000).

In general, no risk exists. The graft materials are very safe in that

all the cells and nonbone proteins are removed. The exception is

fresh-frozen grafts, which have the same risk of viral transmission as

a blood transfusion (~1 in 500,000).