CHAPTER 73 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 73 – Management of Arthrofibrosis of the Knee

Kurt Spindler, MD

Decreased range of motion is a primary concern after virtually any type of injury or surgery about the knee. Arthrofibrosis is generally defined as a loss in range of motion secondary to the buildup of dense intraarticular scar tissue. This complication can be difficult to prevent and even more difficult to predict. Extra-articular lesions, such as capsule and muscle contractures, can also contribute to the patient’s motion deficit. The motion loss can be in the direction of flexion, extension, or both and varies in severity. Most patients will tolerate a loss of flexion better than a loss of extension, as extension loss makes ambulation both more difficult and energy intensive by altering gait mechanics and placing increased strain on structures around the knee.

Although arthrofibrosis is most commonly seen after surgery or injury to the knee, it can also occur in the face of sepsis, neurologic deficits that compromise motion, complex regional pain syndrome, and other inflammatory processes. Nonoperative treatment, including supervised physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, oral or intraarticular steroids, and narcotic pain relievers, are the mainstay of treatment and are successful in resolving the majority of cases. Unfortunately, a significant number of patients will be refractory to conservative treatment and require operative intervention.

Historically, the operative procedures used were open techniques that allowed the débridement of intraarticular scar tissue and the release of tight capsular structures. Arthroscopy is now the mainstay of treatment, allowing both débridement and releases with minimal additional morbidity. The surgical procedures most commonly associated with arthrofibrosis are intraarticular ligament reconstruction and total knee arthroplasty. Several published articles have addressed possible causes or predisposing factors leading to postoperative decreased range of motion. Contributing factors include surgery performed acutely after injury, injury that involves the proximal aspect of the medial collateral ligament, poor preoperative motion, and improper placement of reconstruction grafts. There is, however, no clear consensus on causation.

The incidence of stiffness after knee surgery as reported by various authors varies from as low as 4% to as high as 57% and represents a heterogeneous mix of injury caused versus postoperative patients, making it difficult to fully assess the extent of this condition. Studies have shown a correlation between the development of arthrofibrosis postoperatively and the presence of preoperative irritation and limited range of motion, along with poorly controlled perioperative pain. It has also been suggested that early postoperative rehabilitation and timely intervention, when necessary, can minimize the risk for development of arthrofibrosis.

The timing of operative intervention for arthrofibrosis is a factor that has a large impact on the ultimate success or failure of treatment. Early intervention has been shown to have better outcomes than those of procedures undertaken later. In general, after the first 3 months following injury or surgery with use of an early and aggressive physical therapy program, any remaining flexion or extension deficit should be approached surgically. This time frame allows a reasonable attempt at nonoperative resolution of knee stiffness but does not give the proliferating scar tissue adequate time to mature. After 9 months to a year, surgical procedures will have a lower chance to regain and, just as important, to maintain an increase in range of motion because of scar maturation and extra-articular contracture of the capsule and surrounding musculature.

The range of motion of the knee preoperatively can provide insight into the likely areas of pathologic change. If the knee lacks extension, the pathologic process is often in the intercondylar notch region. A lack of flexion usually indicates exuberant tissue in the suprapatellar pouch or the medial and lateral gutters. In the case of arthrofibrosis that follows total knee arthroplasty, the scar tissue often encompasses the entire intraarticular space.

Physical examination of a knee with arthrofibrosis often reveals more than just a loss of motion. Swelling, effusion, and warmth about the joint, typical of an inflammatory process, are common. Because the majority of these cases follow trauma or surgery to the knee, pain is often a presenting factor. Atrophy of the musculature and an antalgic gait are seen in more progressed instances. It is important to accurately assess the amount of flexion and extension that the joint exhibits, along with a history of the inciting events and their time line. A joint that demonstrates progressive and worsening loss of motion is typical of a global process of inflammation and scarring. Loss of motion that reaches a limit and then stabilizes is more indicative of a focal process, such as the “cyclops” lesion that can develop in the anterior knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Preoperative imaging is of marginal value in arthrofibrosis, especially in postoperative patients well known to the surgeon. Plain radiographs may demonstrate a distal position of the kneecap, known as patella infra, and may show evidence of soft tissue calcification, especially in long-standing cases. Post-reconstruction bone scans are not routinely obtained as they will continue to show increased uptake as a result of the previous surgical intervention. Magnetic resonance imaging adds little to the preoperative assessment of arthrofibrosis. The proliferative soft tissues may be visualized in various compartments of the joint, including the cyclops lesion in the anterior aspect of the knee, but these are of little value for preoperative planning and usually do little to alter decision-making.

Extrinsic factors that might influence knee function also need to be considered. Neurologic impairment that causes weakness about the knee will not be altered by removal of intraarticular scar tissue. Furthermore, surgical insult to a knee that does not function normally may lead to additional scarring. The same holds for a knee joint showing signs of an inflammatory process. Without proper prior medical treatment of the underlying pathologic process, surgical intervention may worsen the situation. Sepsis of the knee poses an interesting situation in that the operative intervention to clear the pathologic process, arthroscopic lavage and débridement, can also be used to remove proliferative scar tissue. If scar tissue recurs after resolution of the infection, repeated arthroscopy can remove this tissue easily.

A firm contraindication to operative intervention for arthrofibrosis is complex regional pain syndrome. This difficult and multifactorial entity is often made worse by surgical procedures. Standard treatment of complex regional pain syndrome should be undertaken and the condition improved or stabilized before an attempt at arthroscopic treatment of stiffness is undertaken. Softer contraindications to surgery include concomitant medical problems and a patient who is not motivated (or able) to cooperate with postoperative therapy.

With the decline in need for open procedures, the patient is positioned in the usual manner for knee arthroscopy. A thigh tourniquet is applied, and the knee is prepared and draped in a flexed position with the table end at 90 degrees. The tourniquet is inflated only if bleeding is encountered during the case that cannot be controlled with arthroscopic cautery. A straight post, rather than a standard knee holder, is positioned along the outside of the thigh at the level of the tourniquet to allow full manipulation of the knee after removal of the scar tissue while the patient is still anesthetized.

Specific Steps (

Box 73-1

)

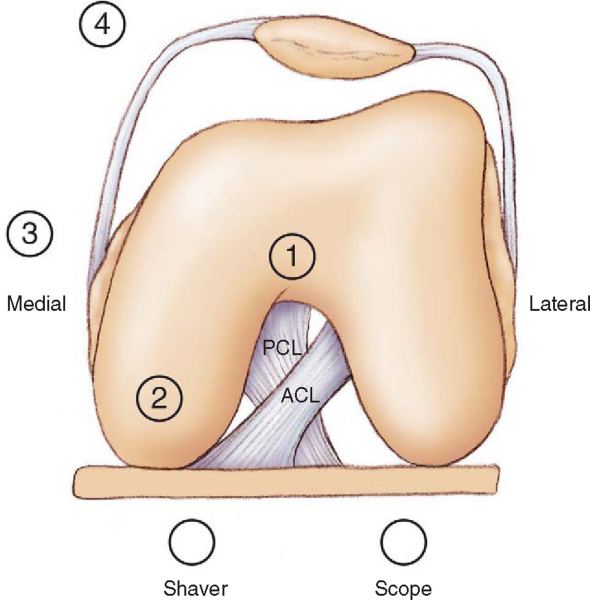

The first step in the procedure is to establish the portals. With decreased motion of the knee and swelling secondary to proliferative intraarticular soft tissue, finding the joint line as a surgical landmark can be difficult. When possible, a mark is made to indicate the medial and lateral joint lines, and the portals are then established on the basis of the markings (

Fig. 73-1

). An anterolateral portal is made just above the joint line and a few millimeters lateral to the edge of the patellar tendon. If the joint line is not discernible, the inferior border of the patella can serve as a reference. By drawing a horizontal line across the knee at this level, the initial portal can be made one fingerbreadth (i.e., approximately 2 cm) lateral to midline so that it bisects this line.

| Surgical Steps | |||||||||||||||

|

2. Establish Initial Working Space

If the knee has some motion preoperatively, indicating preservation of some of the normal intraarticular spaces, the cannula and trocar are advanced into the suprapatellar pouch through the anterolateral portal in the standard fashion. An inspection of the knee, with appropriate picture documentation, is completed as much as allowed by the intraarticular scar tissue. With use of the arthroscope to visualize the anterior medial compartment, a spinal needle is placed to localize the anteromedial portal, and this portal is then established. Once again, if there is insufficient space to visualize the spinal needle, the inferior patellar line can serve as a reference for this portal, placing it 2 cm medial to midline and bisecting the horizontal mark.

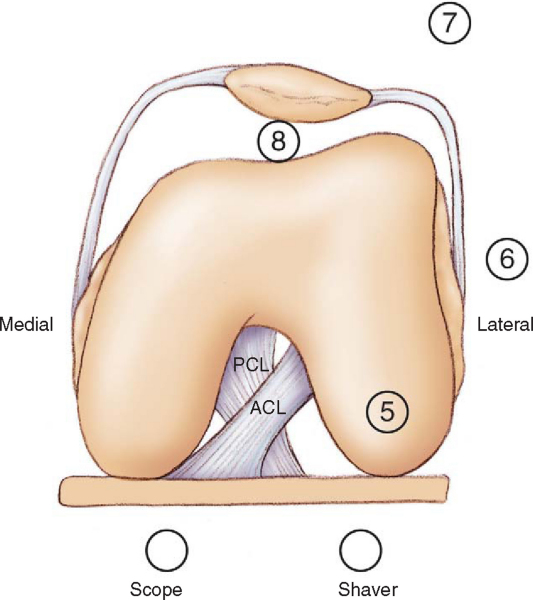

In a knee with minimal motion due to abundant scar tissue or, more commonly, after a total knee arthroplasty, it is not possible to insert the camera and tools in the usual fashion. Débridement of a knee with extensive scarring requires diligence. The previously described landmarks are made on the patient’s skin. The anterolateral portal is made, and the cannula and trocar are inserted into the notch. The anteromedial portal is then made, and a shaver is inserted through this portal directed at the notch. In the intercondylar area behind the patellar tendon and fat pad, the shaver is located and visualized. With care taken not to engage the fat pad for avoidance of excessive bleeding, the scar tissue in the notch is then carefully débrided to establish a working space. Once a working area has been established, the camera and tools can be advanced outward toward the medial and lateral gutters (

Fig. 73-2

).

3. Complete Débridement Throughout Knee

On the basis of the amount and location of the pathologic process as identified by arthroscopy, a 4.5- or 5.5-mm shaver is inserted into the medial portal to begin débridement of the scar tissue in the medial compartment. An arthroscopic punch tool or the cautery is often needed to establish an edge in the fibrous tissue for the shaver effectively to take hold and to begin débridement of the scar. It is generally possible to work through the scar tissue until a plane appears between the scar and the more normal appearing capsular tissue. Development of this plane with the shaver or punch will allow sufficient removal of tissue in the various compartments of the knee. The medial gutter is débrided of its scar tissue burden. With the intercondylar notch and gutter cleaned out, débridement can proceed up into the suprapatellar pouch. This pattern is then reversed and repeated for the lateral compartments (

Fig. 73-3

).

Once the fibrous soft tissues have been removed from the compartments of the knee, an inspection can now be completed. A full inspection of the medial and lateral gutters, the suprapatellar pouch, and the intercondylar notch is required to ensure that adequate tissue has been removed. In general, this is a slow and time-consuming process, and patience is required to correctly establish the planes of dissection and to remove sufficient scar.

5. Manipulation Under Anesthesia

After débridement of the intraarticular scar tissue, a gentle manipulation can be performed on the knee. If there is an extension deficit, the knee can be supported by the heel and gentle downward pressure applied in a constant manner to the anterior knee, attempting to stretch and to release any tissue that might be preventing extension (

Fig. 73-4

). Similarly, manipulation can be used for lack of flexion. The hip is flexed to 90 degrees and the back of the knee supported while a gentle, steady two-finger pressure is applied to the lower leg in an attempt to release any tissue hindering flexion (

Fig. 73-5

). Care must be taken to use gentle pressure in both these maneuvers; excessive force or bouncing might cause unwanted damage, such as fracture. Once the manipulation has been completed, the range of motion should again be assessed and documented.

The patient is seen 5 to 7 days postoperatively for inspection of the surgical site and evaluation of motion. Sutures can be removed from portals if they are well healed. Range of motion should be documented.

The patient is placed into a straight knee immobilizer and allowed immediate weight bearing as tolerated. Physical therapy begins on postoperative day 1, with range-of-motion exercises, quadriceps strengthening, and patellar mobilization. Therapy is ideally conducted every day for the first 2 weeks and then at least three times per week thereafter. An emphasis is placed on increasing range of motion steadily with the goal of achieving the same measurements gained in the operating room, although this is often difficult to achieve fully. On occasion, patients will be unable to regain full or nearly full extension, despite therapy and intraarticular débridement, and open posterior capsular release will be required. The description of this procedure is beyond the scope of this chapter but is covered in several of the provided references.

Typical problems to watch for include hematoma, compartment syndrome from fluid extravasation, infection, and loss of motion.

The best treatment for arthrofibrosis of the knee is prevention. Through the use of anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, adequate pain control, and early rehabilitation programs, postoperative patients can achieve their maximal range of motion and avoid this potentially debilitating complication.

With early recognition and timely intervention, arthrofibrosis can often be treated successfully. In patients with discrete lesions or less dense scarring, better results have been reported than in patients with extensive scarring. Through diligent postoperative physical therapy, many patients will experience a significant recovery of motion and maintain the gains achieved in the operating room (

Table 73-1

).

| Author | No. of Patients | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Mayr et al[3] (2004) | 223 | 96.8% improved |

| Noyes et al[5] (2000) | 23 | All full extension |

| Millett et al[4] (1999) | 8 | All satisfactory (open) |

| Shelbourne et al[7] (1996) | 16 | 1 unsuccessful, 5 not full extension |

| Cosgarea et al[1] (1994) | 37 | 36 satisfactory |

| Steadman et al[8] (1993) | 44 | 33 excellent, 8 good, 1 fair, 2 poor |

| Noyes et al[6] (1992) | 207 | 205 satisfactory |

| Harner et al[2] (1992) | 27 | All satisfactory, 6 required open procedures |

1.

Cosgarea AJ, DeHaven KE, Lovelock JE: The surgical treatment of arthrofibrosis of the knee.

Am J Sports Med 1994; 22:184-191.

2.

Harner CD, Irrgang JJ, Paul J, et al: Loss of motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:499-506.

3.

Mayr HO, Weig TG, Plitz W: Arthrofibrosis following ACL reconstruction—reasons and outcome.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124:518-522.

4.

Millett PJ, Williams RJ, Wickiewicz TL: Open débridement and soft tissue release as a salvage procedure for the severely arthrofibrotic knee.

Am J Sports Med 1999; 27:552-561.

5.

Noyes FR, Berrios-Torres S, Barber-Westin SD, Heckmann TP: Prevention of permanent arthrofibrosis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction alone or combined with associated procedures: a prospective study in 443 knees.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2000; 8:196-206.

6.

Noyes FR, Mangine RE, Barber SD: The early treatment of motion complications after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament.

Clin Orthop 1992; 277:217-228.

7.

Shelbourne KD, Patel DV, Martini DJ: Classification and management of arthrofibrosis of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Am J Sports Med 1996; 24:857-862.

8.

Steadman JR, Burns TP, Peloza J, et al: Surgical treatment of arthrofibrosis of the knee.

J Orthop Tech 1993; 1:119-127.

DeHaven et al., 2003.

DeHaven KE, Cosgarea AJ, Sebastianelli WJ: Arthrofibrosis of the knee following ligament surgery.

Instr Course Lect 2003; 52:369-381.

Kim et al., 2004.

Kim DH, Gill TJ, Millett PJ: Arthroscopic treatment of the arthrofibrotic knee.

Arthroscopy 2004; 20:187-194.

Lidenfeld et al., 2000.

Lidenfeld TN, Wojtys EM, Husain A: Surgical treatment of arthrofibrosis of the knee.

Instr Course Lect 2000; 49:211-221.

Petsche and Hutchinson, 1999.

Petsche TS, Hutchinson MR: Loss of extension after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament.

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1999; 7:119-127.

Shelbourne and Patel, 1999.

Shelbourne KD, Patel DV: Treatment of limited motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1999; 7:85-92.