CHAPTER 70 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

Section – Other Surgical Techniques of the Knee

CHAPTER 70 – Medial Collateral Ligament Repair and Reconstruction

Timothy J. Henderson, MD

Injury to the medial ligamentous structures of the knee is one of the most common ligament injuries involving the knee. [1] [9] The treatment of medial-sided knee injuries has evolved from aggressive surgical treatment in the past to nonoperative treatment of most of these injuries currently. Although the majority of isolated medial-sided knee injuries can be treated nonoperatively, with full return to function expected, [3] [4] [6] many complex medial-sided knee injuries or injuries combined with other ligament disease may require surgical intervention.

The common mechanism of injury to the medial structures of the knee is secondary to the knee’s being subjected to a valgus force either from a direct lateral blow or from the foot’s being planted and the body’s imparting a valgus force to the knee.[6] With increased force, additional injuries to the cruciates may occur.

The severity of injury to the medial collateral ligament (MCL) may be graded according to its stability in resisting a valgus stress at 30 degrees of knee flexion. A grade I injury, which is described as a partial tear to the MCL, exhibits tenderness over the course of the ligament and pain with valgus stress as well as abnormal laxity limited to 5 mm or less with valgus stress.[5] A grade II injury exhibits tenderness to palpation and to valgus stress, no laxity at 0 degrees, and 5 to 9 mm of opening at 30 degrees of flexion (in comparison with the unaffected side).[5] Grade I and grade II injuries have definite endpoints to valgus stress on physical examination. A grade III injury represents complete rupture of the medial ligaments with tearing of the deep capsular structures. Examination of a grade III injury allows opening at 0 degrees (variable, depending on the presence or degree of injury to the cruciates) and at 30 degrees of flexion. A grade III injury indicates medial opening of 10 mm or more.[5] There is no firm endpoint to valgus stress at 30 degrees of flexion. Opening of more than 5 to 10 mm in full extension should suggest other associated ligament and capsular injuries.

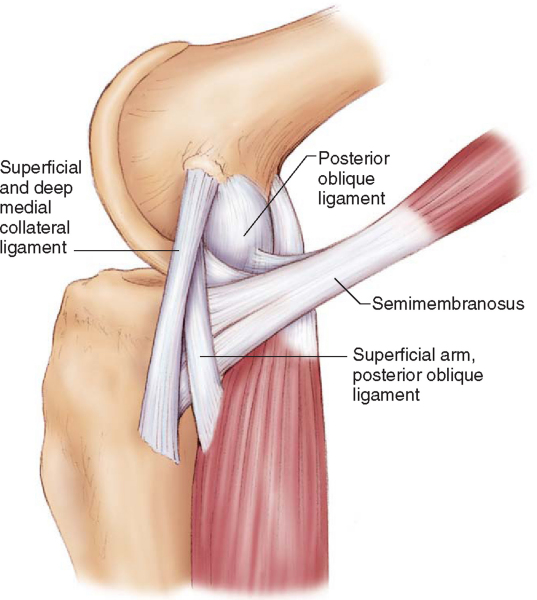

Common to medial-sided knee injuries are injuries to the posteromedial corner. The posterior medial corner consists of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, the posterior oblique ligament (POL), and the semimembranosus muscle and its expansions. [2] [4] [11] It is believed by many authors that the posteromedial corner operates in a coordinated fashion throughout normal range of motion as both a static and a dynamic restraint to anteromedial rotary instability.[4]

The medial complex of the knee has been described as a sleeve of tissue extending from the midline anteriorly to the midline posteriorly. The important static structures (

Fig. 70-1

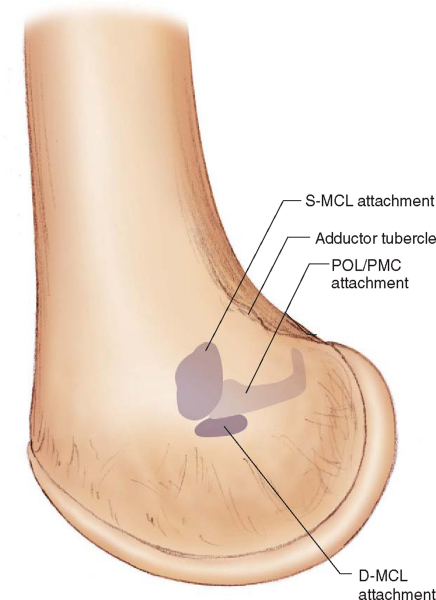

) responsible for valgus stability are the superficial MCL, the deep MCL, and the POL. [2] [12] Dynamic support is provided by the aforementioned posterior medial corner structures. The superficial MCL runs from the medial femoral epicondyle proximally, anterior to the adductor tubercle (

Fig. 70-2

), and inserts on the anteromedial tibia 4 to 7 cm distal to the joint line, beneath the insertion of the pes anserinus. It is between 9 and 11 cm long and 1 to 2 cm wide.[2] The anterior parallel fibers of the superficial MCL are in constant tension throughout flexion, whereas the posterior fibers are oblique and lax in flexion. [1] [2] The deep MCL is a short structure deep to the superficial MCL; it attaches to the medial meniscus.[11] Whereas the deep MCL can be separated from the superficial MCL distally, the fibers of both structures fuse proximally. The POL (also referred to as the posterior medial capsule) is a triangular capsular ligament originating posterior to the superficial MCL at the adductor tubercle and inserting just below the joint line at the flare of the proximal medial tibia.[2] It is approximately 5 cm long and 0.5 cm wide.[10] Approximately one third of the POL fibers are attached to the posterior horn of the medial meniscus; two thirds pass directly from the femur to the tibia.[4] The POL becomes lax in flexion, and it is theorized that to function, it must be dynamized by the pull of the attached semimembranosus.[2]

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-1 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-2 |

Radiographs to evaluate the injured knee include the standard anteroposterior, lateral, and patellofemoral views. Films should be evaluated for fractures, ligament avulsions, and lateral capsular signs such as the Segond fracture, loose bodies, and Pellegrini-Stieda lesions. Stress radiographs are important in adolescents to rule out potential epiphyseal lesions.

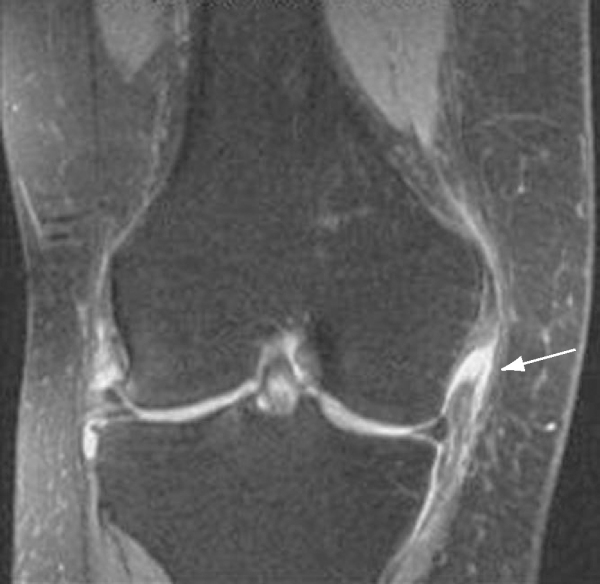

Magnetic resonance imaging is a valuable tool to identify not only meniscal and cruciate pathologic changes but also the location of the MCL injury (

Fig. 70-3

). [9] [10] This can aid greatly at the time of surgery by helping to locate the zone of injury and the area in need of repair.[8] If a magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of an MCL tear demonstrates a type I lesion (located at the femoral origin), the likelihood of nonoperative treatment being effective is high. If a type III lesion is encountered (a tear from the femoral origin that extends distally across the joint line), the chance of successful nonoperative treatment is low, and the possibility that residual chronic laxity will remain is significant.[9]

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-3 |

Although it is commonly accepted that isolated tears of the MCL, regardless of grade, can be treated with early functional rehabilitation and bracing, the treatment of torn medial ligaments associated with other ligamentous injuries is still controversial. [1] [2] [3] [6] Some authors advocate reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with nonoperative treatment of the medial structures; others report satisfying results with combined medial ligament repair and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Nevertheless, combined grade III MCL and cruciate ligament injuries can lead to complex symptomatic instability because the functional deficiency of one ligament may affect the healing of the other. [3] [9] Less commonly, isolated grade III injuries, after a trial of nonoperative treatment, may heal with residual symptomatic medial instability.

Surgical repair or reconstruction of the medial ligamentous complex may be recommended if there is a chronic grade III MCL injury with symptoms of instability with excessive medial joint line opening to valgus stress.[3]

Examination Under Anesthesia and Positioning

At the time of surgery, a knee examination under anesthesia is performed to help confirm the suspected diagnosis and to rule out other ligament deficiencies. The patient is positioned supine on the operating table, and a tourniquet is placed as high as possible on the operative leg. Suture anchors, interference screws, a tendon harvester, and an allograft (on standby) should be available before the procedure is started. Care should be taken to ensure that the operative leg may be easily placed in a figure-four position to allow medial exposure (

Fig. 70-4

).

Specific Steps (

Box 70-1

)

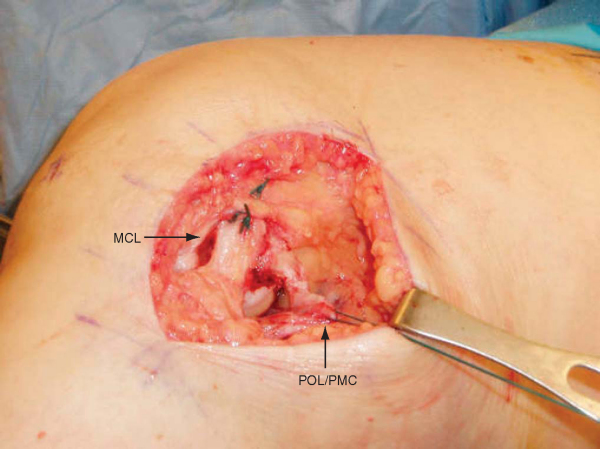

We agree with Muller[7] and have found that there is often sufficient local tissue for repair and that a graft is not usually necessary. We avoid arthroscopy before repair of MCL injuries. We have found that arthroscopy may cause normally be easily ident isignificant fluid extravasation into the soft tissues, making dissection more difficult. The leg is exsanguinated with the use of an Esmarch bandage, and the tourniquet is inflated to 300 mm Hg. The leg is placed in the figure-four position, which should allow excellent exposure to the medial aspect of the knee. An 8-cm incision is made on the medial aspect of the knee coursing over the medial epicondyle (

Fig. 70-5

). The saphenous vein and nerve should be identified and protected when possible during the approach.[12] The sartorius fascia is incised and retracted anteriorly and posteriorly. The superficial MCL as well as the POL can normally be easily identified (

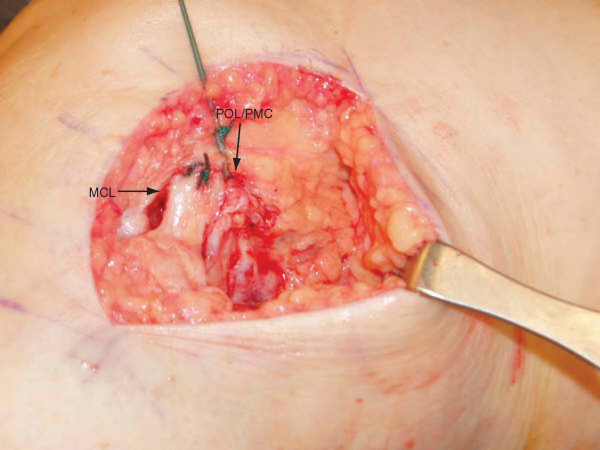

Fig. 70-6

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-6 |

The site of injury to the MCL will dictate the operative technique. Ligaments torn from their bone attachments should be reattached to their anatomic origins. If the MCL is torn proximally, it should be advanced to the medial epicondyle and repaired with the knee flexed to 30 degrees, under a varus-directed force, and with moderate tension (

Fig. 70-7

). Staples, suture anchors, or nonabsorbable sutures placed through drill holes can be used. If the MCL is torn at its distal insertion, it should be advanced to its distal insertion beneath the pes anserinus and fixed in a similar fashion. Similarly, fixation can be performed with ligament screws and washers, suture anchors, or No. 5 nonabsorbable sutures placed through drill holes in the bone. Once the superficial MCL is repaired, the POL is advanced and repaired to the adductor tubercle proximally and to the posterior edge of the repaired MCL (

Fig. 70-8

). Posterior to and confluent with the POL will be the posterior medial capsule and its connection to the semimembranosus. If these structures are disrupted or lax, they should be advanced to the POL and included in the repair. Acute midsubstance ruptures of the superficial MCL or the POL can be repaired primarily with suture.

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-7 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-8 |

If the tissue quality of the superficial MCL is poor or the ligament tear is such that it cannot be repaired anatomically, consideration should be given to use of a tendon graft, although we have rarely found this to be necessary. If additional ligamentous injury and reconstruction are needed on the affected knee, we may recommend an allograft to limit additional operative morbidity. If the medial injury is the only ligamentous reconstruction to be performed, an autograft may be an acceptable choice.

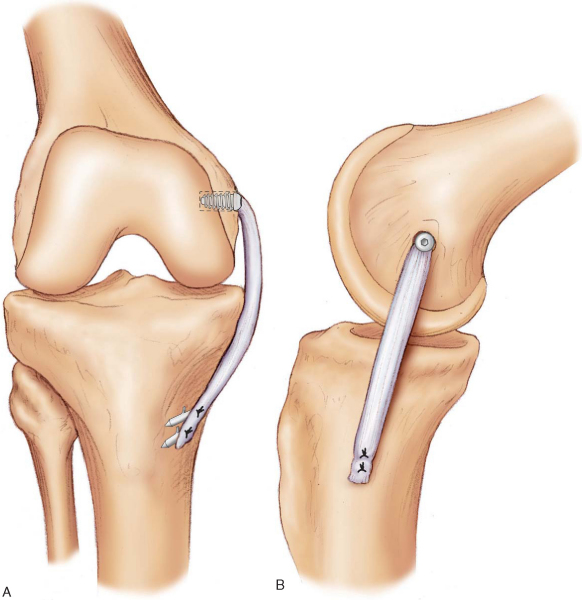

Autogenous reconstruction can be accomplished with the use of a harvested semitendinosus or a gracilis tendon.[3] The hamstring tendons are harvested in the standard fashion[3] and are fashioned into double-bundle tendon grafts. The graft should be positioned proximally at the medial epicondyle and may be fixed with an EndoButton or with an interference screw technique. If interference screw fixation is preferred, the diameter of the graft is measured, and an appropriately sized tunnel is reamed to a depth of 25 to 30 mm. The graft sutures from the looped end are placed in the eyelet of the guide pin and pulled through the lateral cortex. A 25-mm soft tissue interference screw, the same size as the graft tunnel diameter, is placed in the tunnel to fix the graft. The position of the distal end of the graft is approximated with the use of the remaining fibers of the distal insertion of the MCL. The knee is put through range of motion with the graft tentatively held at the presumptive distal fixation site to test for isometry. A change in graft length of 3 to 4 mm is considered an acceptable amount of excursion.[3] The distal end of the graft is then fixed to the distal insertion site with suture anchors or nonabsorbable sutures placed through drill holes in the bone. Take care to fix the tibial side with the knee held in 30 degrees of flexion[3] as described previously in the repair section (

Fig. 70-9

). The POL can then be advanced anteriorly and proximally and sutured to the reconstructed MCL. It is rarely necessary to reconstruct the POL because there is almost always suitable POL/posterior medial capsular tissue to be advanced and repaired.

|

|

|

|

Figure 70-9 |

The decision to use an allograft for reconstruction can be made to limit morbidity, particularly in the multiple ligament–injured knee. Semitendinosus or tibialis anterior grafts are attractive choices because they are of sufficient size and length to reconstruct the superficial MCL. The allograft reconstruction is performed in a way similar to the autograft reconstruction.

| PEARLS AND PITFALLS | |||||||||||||||

|

Postoperatively, the leg is placed in a hinged knee brace locked in 30 degrees of flexion. The patient is initially non–weight bearing with crutches. The patient may be allowed to undergo protected range of motion from 0 to 90 degrees and protected weight bearing in a hinged knee brace locked in extension at 14 days postoperatively. Our goal is for patients to regain full range of motion at 6 weeks after surgery. The patient may return to full weight bearing at 6 to 8 weeks with the hinged knee brace unlocked, and the physical therapy program may advance to bicycling and closed-chain kinetic exercises. If the medial ligament repair is performed in combination with a cruciate reconstruction, the postoperative protocol should be geared toward the cruciate rehabilitation.

Knee stiffness and the formation of heterotopic bone are complications of acute medial ligament repair.[1] Arthrofibrosis or a knee flexion contracture is minimal if the patient adheres to a regimented rehabilitation program, however.

1.

Beltran J: The distal semimembranosus complex: normal MR anatomy, variants, biomechanics and pathology.

Skeletal Radiol 2003; 32:435-445.

2.

Bosworth D: Transplantation of the semitendinosus for repair of laceration of medial collateral ligament of the knee.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1952; 34:196-202.

3.

Haimes J, Wroble R, Grood E, Noyes F: Role of the medial structures in the intact and anterior cruciate ligament–deficient knee.

Am J Sports Med 1994; 22:402-409.

4.

Hughston J: The importance of the posterior oblique ligament in repair of acute tears of the medial ligaments in knees with and without an associated rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994; 76:1328-1344.

5.

Hughston J, Eilers A: The role of the posterior oblique ligament in repairs of acute medial (collateral) ligament tears of the knee.

J Bone Joint Surg 1973; 55:923-955.

6.

Loredo R, Hodler J, Pedowitz R, et al: Posteromedial corner of the knee: MR imaging with gross anatomic correlation.

Skeletal Radiol 1999; 28:305-311.

7.

In: Muller W, ed. The Knee: Form, Function, and Ligament Reconstruction,

New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983:241-246.

8.

Nakamura N, Horibe S, Toritsuka , et al: Acute grade III medial collateral ligament injury of the knee associated with anterior cruciate ligament tear. The usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging in determining a treatment regimen.

Am J Sports Med 2003; 31:261-267.

9.

Pressman A, Johnson D: A review of ski injuries resulting in combined injury to the anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligaments.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:194-202.

10.

Robinson J, Bull A, Amis A: Structural properties of the medial collateral ligament complex of the human knee.

J Biomech 2005; 38:1067-1074.

11.

Robinson J, Sanchez-Ballester J, Bull A, et al: The posteromedial corner revisited. An anatomical description of the passive restraining structures of the medial aspect of the human knee.

J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86:674-681.

12.

Sims W, Jacobson K: The posteromedial corner of the knee: medial-sided injury patterns revisited.

Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:337-345.