CHAPTER 7 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 7 – Arthroscopic Management of Rare Intraarticular Lesions of the Shoulder

In no other joint is there as much variability in normal anatomy as in the shoulder. Unusual conditions of the shoulder must be differentiated from normal variants. Although most pathologic processes are covered in other chapters, rare lesions such as pigmented villonodular synovitis, osteochondritis dissecans of the glenoid and humerus, traumatic chondral fracture, chondrolysis, synovial osteochondromatosis, ganglion and synovial cysts, blending or bifurcation of the biceps and tearing of the attachment of a Buford complex, reverse humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament with infraspinatus tear, coracoid fracture with extension into the joint, and floating anterior capsule (combined Bankart lesion and humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament) are not commonly encountered within the shoulder.

Each of these entities may require different management. The rarity of these problems complicates diagnosis, preparation, and management. Many are encountered only on entering the joint. It is the goal of this chapter to discuss diagnostic studies and tests that can help preoperatively to identify these conditions correctly and assist with their management.

Most of these patients present with either no trauma or a history of only minor trauma. The exception is the articular fracture, which often has a clear history of a traumatic event, often a dive to the floor during an athletic event, after which pain and limitation of activity occur without physical examination findings. However, in all of these cases, symptoms frequently are not associated with a specific activity. Unlike with rotator cuff disease, the pain and feelings of swelling are not worse at night. Unlike with instability problems, the symptoms are not associated with a particular movement or arm position. Unlike with adhesive capsulitis, there is no consistent loss of motion or pain on inferior glide testing.

Examination usually reveals palpable swelling within the glenohumeral joint, most easily felt in the area of the rotator interval. There is usually some loss of motion, primarily in internal and external rotation. Crepitation is noted with rotational movements of the glenohumeral joint. In cases in which the Buford complex has been avulsed, results of the anterior superior load and shift examination will be positive.

Radiographs are usually normal except in synovial osteochondromatosis, in which multiple loose bodies are noted (

Fig. 7-1

). Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in osteochondritis dissecans lesions, cases of synovial cysts (

Fig. 7-2

), and chondrolysis. Avulsions of a Buford complex, pigmented villonodular synovitis, and articular cartilage fractures will not show up on most radiographic tests. Glenohumeral avulsions are visualized by arthrography, and the coracoid fracture is best noted on computed tomographic scans.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-1 |

Indications and Contraindications

Each of these various entities may be managed by arthroscopy. The main contraindications to arthroscopic surgery are in the patient with pigmented villonodular synovitis. Complete excision may require open surgery.

Most of these cases require general anesthesia, although experienced regional anesthesiologists may certainly use interscalene block anesthesia. I prefer the lateral decubitus position because of its ability to allow easier access to all areas of the shoulder joint, but the surgeon’s preference is usually the rule in these cases.

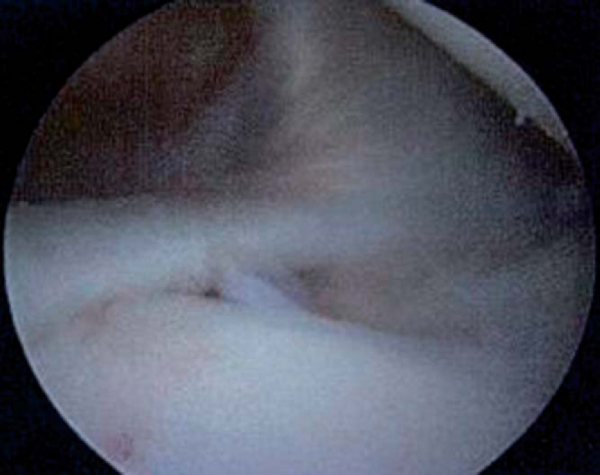

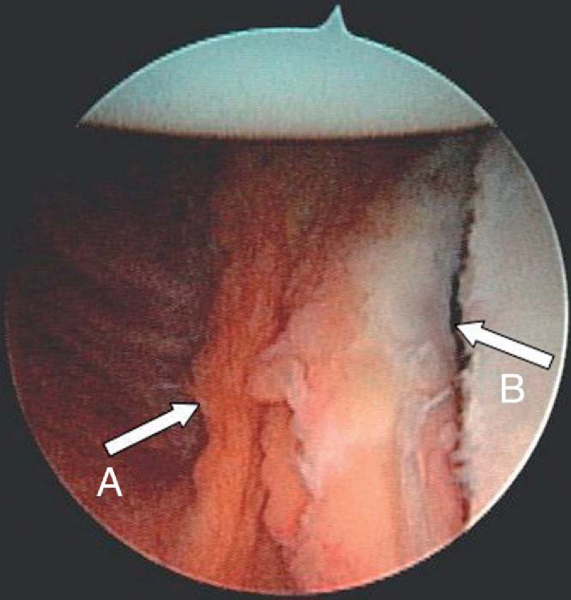

Diagnostic arthroscopy usually reveals the pathologic process. Most of these are readily apparent once the arthroscope is placed within the joint. The avulsion of the Buford complex attachment is the most difficult to differentiate from normal variants. Chondromalacia of the glenoid and fraying of the undersurface of the labrum and outer surface of the glenoid isolated to that area alone and not farther inferior on the glenoid are key findings (

Fig. 7-3

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-3 |

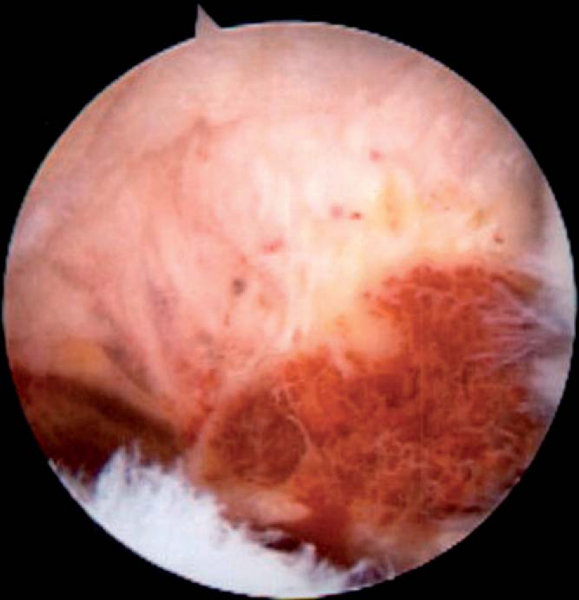

Pigmented villonodular synovitis has the characteristic appearance seen in other joints. However, it is not readily resected as it penetrates through the lining of the joint and expands outward into the surrounding structures (

Fig. 7-4

). Especially in inferior lesions, the synovial growth may envelope the axillary nerve, requiring its dissection either through open surgery or by arthroscopy.

Synovial cysts (

Fig. 7-5

) may be related to labral tears or to foreign body reaction. The cyst should be resected and the associated pathologic lesion repaired or removed.

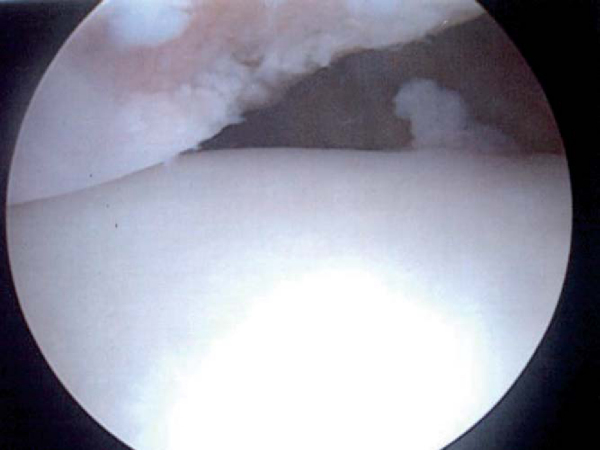

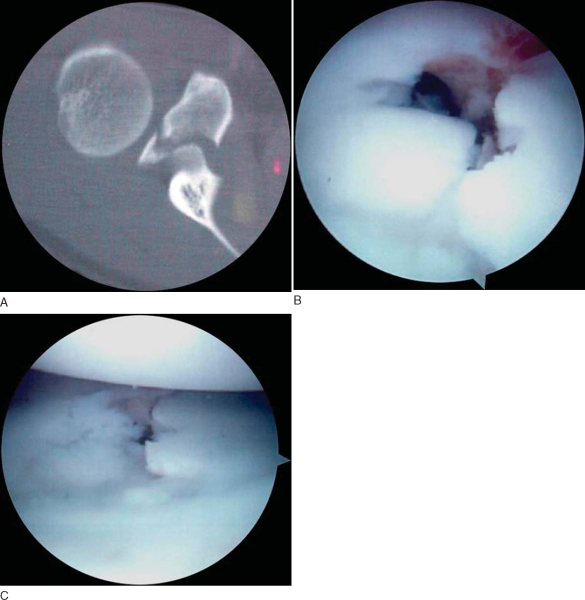

In cases of synovial chondromatosis (

Fig. 7-6

), the multiple loose bodies are readily apparent. It may be useful to place a much larger cannula, such as that used in urologic procedures, to allow the loose bodies to be removed. It is important to find the area of synovium producing the lesions and to excise it. The most common area in which to find this synovium in my experience is the subcoracoid bursa and the bicipital groove.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-6 |

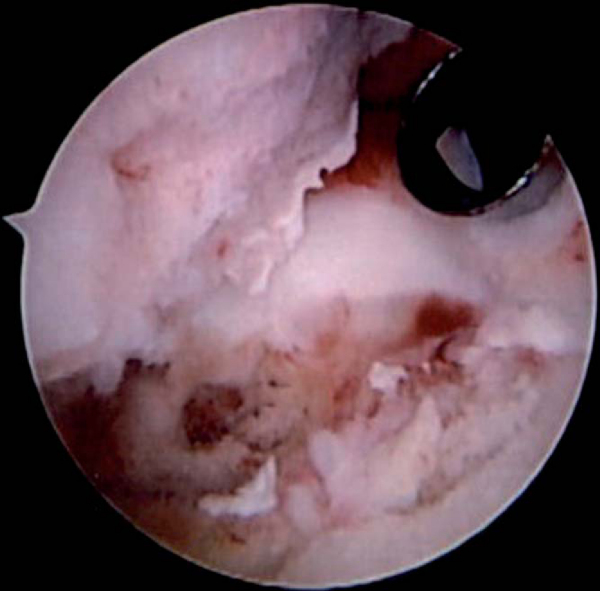

Traumatic chondral defects and osteochondritis of the humeral head or glenoid result in irritation and swelling within the glenohumeral joint. Finding these loose articular pieces within the shoulder joint and their removal will help decrease symptoms (

Fig. 7-7

). The injured bed in the articular surface should also be located and débrided and at least marrow stimulation performed.

The most difficult to manage of these various lesions is chondrolysis of the glenohumeral joint. Although this has been described to follow thermal surgery, the exact cause has yet to be elucidated. Arthroscopy reveals an aggressive destruction of the entire articular surface of the humeral head and glenoid, severe synovitis and capsular damage, and almost an avascular necrosis type of destruction of the humeral head (

Fig. 7-8

). Biologic glenoid resurfacing with or without humeral head replacement seems to provide the best relief.

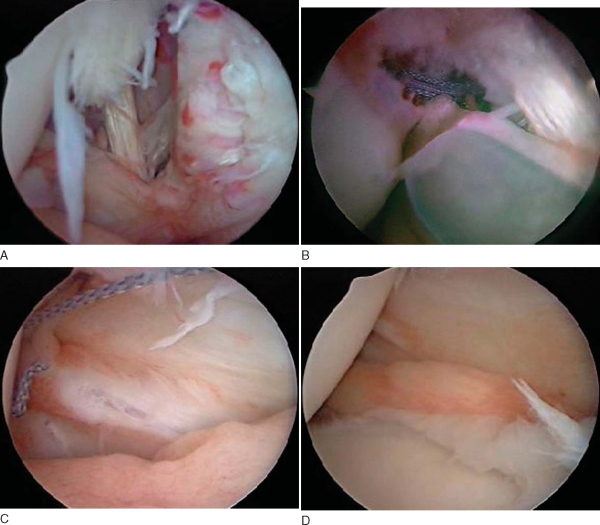

Humeral avulsions of the anterior glenohumeral ligaments are covered elsewhere in this text. However, one may occasionally find this lesion in conjunction with a Bankart lesion (

Fig. 7-9

). In these cases, the Bankart lesion is repaired first, and then the humeral avulsion is repaired. This also represents an excellent indication for open surgery by Matsen’s approach to elevate the lateral subscapularis and use the humeral avulsion to access the Bankart lesion. The capsulolabral complex is repaired to the glenoid, and the humeral avulsion is repaired as part of the reattachment of the lateral capsule and subscapularis tendon.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-9 |

Reverse humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament is even more uncommon. In high-energy trauma, the lateral capsule and the infraspinatus tendon may both be involved, necessitating repair of both the capsule and the tendon with anchors and sutures (

Fig. 7-10

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-10 |

Coracoid fractures are relatively rare lesions in which the fracture may extend into the articular surface of the glenoid. The symptoms are pain, tenderness around the coracoid, and swelling. The fracture is readily visualized on magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomographic scans. Although immobilization often results in union, active individuals may require stabilization. Arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint may allow monitoring of the articular extension while also allowing reduction and fixation (

Fig. 7-11

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-11 |

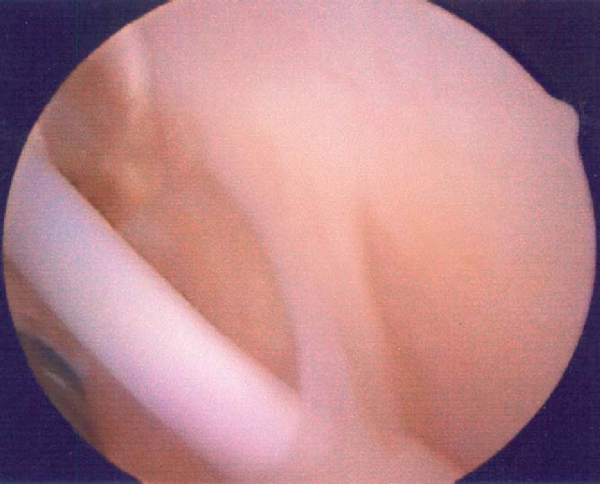

There are many more unusual lesions of the shoulder that may or may not require stabilization. Incorporation of all or part of the biceps into the rotator cuff is a normal variant (

Fig. 7-12

), just like the Buford complex, hypermobile superior labrum, and absent anterior labrum. Before a lesion is repaired, it is incumbent on the surgeon to review the injury, the symptoms, and the physical examination findings to see whether they match the pathologic process that is being viewed. If the mechanism is sufficient to produce the pathologic process being visualized, and the pathologic lesion can produce the symptoms the patient is complaining of, repair is warranted. Elimination of the symptoms after repair may be the only confirmation that the surgeon has performed the correct operation.

Bents and Skeete, 2005.

Bents RT, Skeete KD: The correlation of the Buford complex and SLAP lesions.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14:565-569.

Chiffolot et al., 2005.

Chiffolot X, Ehlinger M, Bonnomet F, Kempf JF: Arthroscopic resection of pigmented villonodular synovitis pseudotumor of the shoulder: a case report with three year followup.

Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2005; 91:470-475.

Debeer and Brys, 2005.

Debeer P, Brys P: Osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral head: clinical and radiological findings.

Acta Orthop Belg 2005; 71:484-488.

Hamada et al., 2005.

Hamada J, Tamai K, Doguchi Y, et al: Case report: a rare condition of secondary synovial osteochondromatosis of the shoulder joint in a young female patient.

J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14:653-656.

Jerosch and Aldawoudy, 2007.

Jerosch J, Aldawoudy AM: Chondrolysis of the glenohumeral joint following arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: a case report.

Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007; 15:292-294.Epub June 24, 2006.

Levine et al., 2005.

Levine WN, Clark Jr AM, D’Alessandro DF, Yamaguchi K: Chondrolysis following arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy to treat shoulder instability. A report of two cases.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:616-621.