CHAPTER 5 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 5 – Arthroscopic Rotator Interval Capsule Closure

Robert A. Arciero, MD

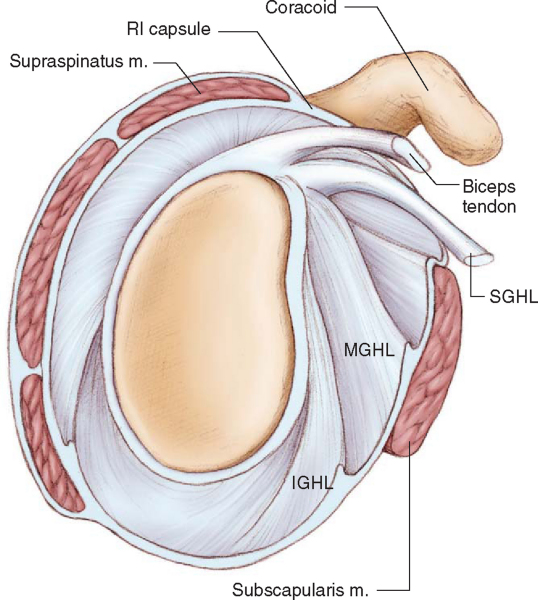

There is growing interest in the role of the rotator interval capsule in shoulder instability. The rotator interval capsule is a triangular area of anterior capsule between the superior border of the subscapularis inferiorly, the anterior margin of the supraspinatus superiorly, the coracoid process medially, and the intertubercular groove laterally (

Fig. 5-1

). The superior glenohumeral ligament and coracohumeral ligament are structural components of this capsule. Cole et al[6] demonstrated that most of the remaining interval capsule is thin and poorly organized tissue.

Harryman et al[9] demonstrated the importance of the rotator interval capsule in glenohumeral motion and stability. Their study concluded that the role of the interval capsule is to decrease inferior translation in the adducted shoulder and to limit posterior translation in the flexed shoulder. Van der Reis and Wolf[18] demonstrated in a cadaver model that glenohumeral translation and motion could be decreased with arthroscopic rotator interval imbrication.

Imbrication of the rotator interval capsule has become a standard part of open instability procedures since it was first advocated by Neer in 1980.[15] Recent advances in arthroscopic surgery have allowed surgeons to duplicate the open techniques with respect to labral repair and capsular shift. Numerous authors have also described arthroscopic techniques of rotator interval capsular imbrication that are used as part of anterior, posterior, or multidirectional instability procedures. [2] [4] [5] [8] [12] [14] [17] We describe a simple technique of rotator interval capsular imbrication with use of nonabsorbable suture.

|

|

|

|

Figure 5-1 |

A focused history is essential in the diagnosis and management of shoulder instability.

The presence or absence of trauma, the mechanism of injury, and the position of the arm when symptoms occur offer important clues to the direction and extent of the shoulder instability. A history of the arm “dropping out the bottom” is particularly concerning for a lax interval capsule.

Examination of the cervical spine, areas of tenderness, and range-of-motion and motor strength testing are performed to rule out other sources of shoulder disease. The anterior and posterior apprehension-relocation tests as well as the load and shift test are important in determining the presence and direction of glenohumeral instability. A sulcus sign greater than 2 cm that persists with external rotation of the adducted arm is a crucial indicator of an incompetent rotator interval capsule (

Fig. 5-2

). The presence of ligamentous laxity may influence the decision to imbricate the rotator interval capsule.

Plain radiographs including a true anteroposterior view of the glenohumeral joint and a West Point axillary view are obtained for all patients to assess glenoid and humeral head bone loss. Magnetic resonance imaging, with or without the intraarticular administration of gadolinium, is performed to assess for labral disease.

Indications and Contraindications

Rotator interval capsule closure is indicated in conjunction with an arthroscopic stabilization procedure such as a labral repair (anterior, posterior, or superior) or as part of an arthroscopic capsular plication. Patients with a component of inferior instability demonstrated by a significant sulcus sign are proper candidates for an interval capsule imbrication. In addition, most patients with posterior shoulder instability require an interval capsule imbrication as basic science research demonstrates the importance of the interval capsule in resisting posterior translation.

Contraindications include patients who are not candidates for an arthroscopic stabilization. Patients with significant bone loss or true voluntary instability secondary to a psychological disorder are not candidates for rotator interval imbrication. We do not routinely close the rotator interval capsule in patients undergoing stabilization for primary, unidirectional, traumatic instability.

Arthroscopic shoulder stabilization and rotator interval capsule closure require a significant amount of specialized equipment. Large disposable cannulas, devices to shuttle suture, suture anchors, and specialized hand-held instruments are required to perform the procedure.

Arthroscopic rotator interval capsule closure can be safely performed under general or interscalene regional anesthesia. The patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or beach chair position on the basis of the surgeon’s preference. A shoulder-specific positioner and arm holder is helpful (

Fig. 5-3

).

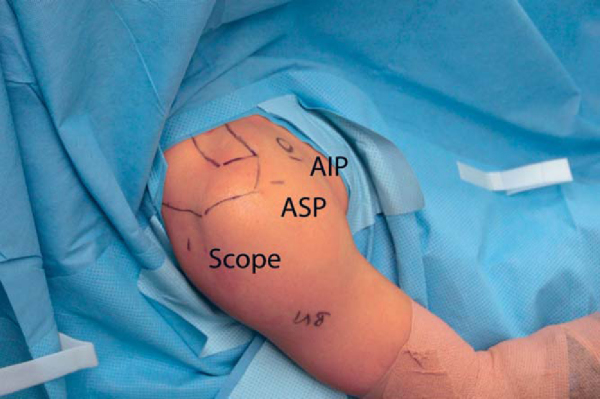

Surgical Landmarks, Incisions, and Portals

Portal location is usually determined by the concomitant procedures performed before the rotator interval capsule closure. Most frequently, a 30-degree arthroscope is used through a standard posterior portal, and dual cannulas are placed anteriorly (

Fig. 5-4

). One cannula is placed through an anterior superior portal entering the joint just below the biceps tendon. A second cannula is placed through the anterior inferior portal entering the joint just above the subscapularis tendon (

Fig. 5-5

). These portals allow repair of most anterior labral lesions and anterior capsular plication. Additional accessory portals are often required for superior or posterior labral repairs.

|

|

|

|

Figure 5-4 |

Examination Under Anesthesia and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

An examination under anesthesia is performed to assess range of motion and shoulder stability. The load and shift test is performed to determine anterior and posterior instability. The sulcus test is performed with the arm at neutral rotation and in external rotation to assess inferior instability.

A careful diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to evaluate for evidence of instability, including labral tears, biceps fraying, superior subscapularis fraying, and chondral scuffing. The rotator interval capsule is evaluated arthroscopically, although there is no consensus on what constitutes a lax interval capsule. Fitzpatrick et al[7] suggest that the interval is widened if it is seen extending superior to the biceps tendon.

Specific Steps (

Box 5-1

)

1. Concomitant Stabilization Procedures

The initial step in arthroscopic stabilization after cannula placement is repair of any associated labral disease. The anterior or posterior capsule is then plicated as indicated. The details of these procedures are discussed elsewhere in this text.

| Surgical Steps | |||||||||||||||

|

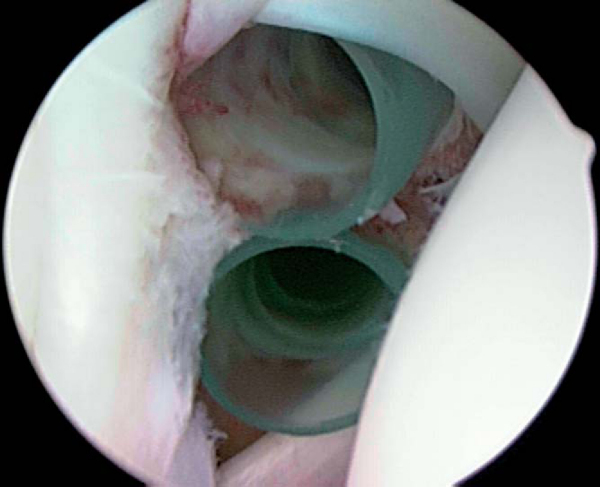

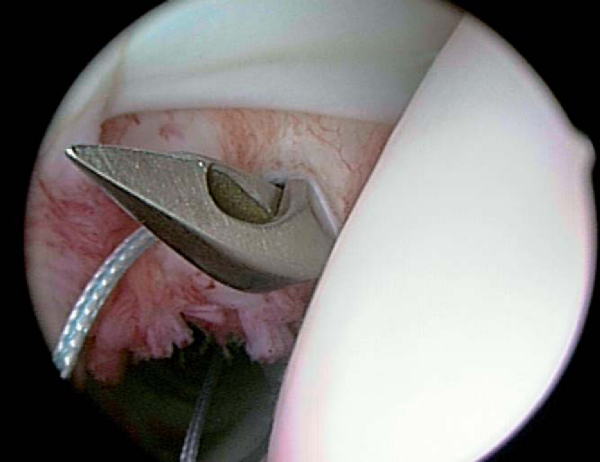

2. Piercing the Middle Glenohumeral Ligament

A No. 2 nonabsorbable suture is loaded into a straight tissue penetrator (

Fig. 5-6

). The penetrator is placed through the anterior inferior portal cannula (

Fig. 5-7

) and pierces the middle glenohumeral ligament just above the subscapularis (

Fig. 5-8

). A suture grasper is placed in the anterior superior portal cannula, and the end of the nonabsorbable suture is transported out the cannula (

Fig. 5-9

).

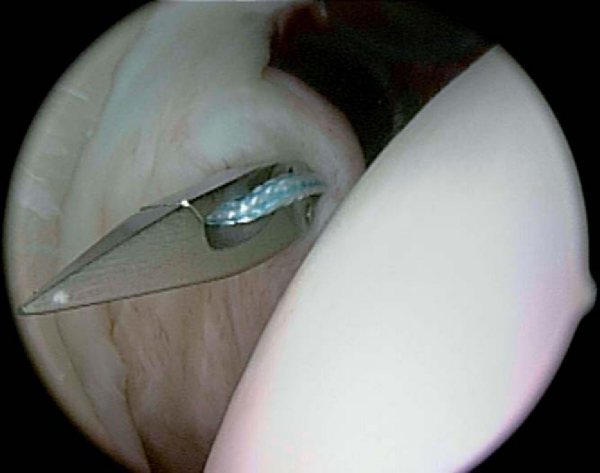

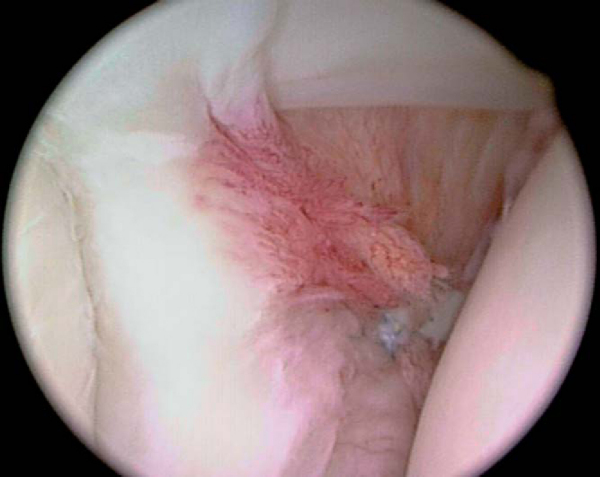

3. Piercing the Superior Glenohumeral Ligament

The anterior superior portal cannula is carefully backed out of the glenohumeral joint so it is positioned just outside the capsule. An angled tissue penetrator is placed through this cannula (

Fig. 5-10

), and the superior glenohumeral ligament is pierced (

Fig. 5-11

). The limb of the suture that is still within the anterior inferior portal cannula is grasped anterior to the middle glenohumeral ligament (

Fig. 5-12

). This limb of suture is transported out the anterior superior portal.

The anterior inferior portal cannula is removed. Both limbs of the suture are exiting the anterior superior portal cannula, which still traverses the subcutaneous tissue and deltoid muscle but sits just outside the capsule (

Fig. 5-13

). The shoulder is positioned in 45 degrees of abduction and 45 degrees of external rotation to prevent loss of external rotation, and tension is applied to the sutures (

Fig. 5-14

). The middle and superior glenohumeral ligaments will be brought together as the rotator interval capsule is imbricated. A sliding-locking arthroscopic knot is tied and advanced until the knot can be felt contacting the capsule. This knot is not visible from within the joint. Two or three half-hitch throws can be placed. An end-cutting suture cutter is slid down the suture and the knot is cut. This is performed with tactile feedback as the knot is extracapsular and not visible. Shoulder range of motion is checked to ensure that there has not been an excessive loss of external rotation.

The portals are closed in a standard fashion. Local anesthetic can be instilled into the joint or a pain pump can be placed, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The patient is placed into a shoulder immobilizer in internal rotation and slight abduction if an anterior stabilization procedure was performed. An external rotation sling is used if the posterior labrum was repaired.

Most patients are sent home the day of surgery. Sutures are removed at 7 to 10 days.

The postoperative rehabilitation is determined by the primary stabilization procedure performed. In general, a sling is worn for 4 weeks with the arm in internal rotation after an anterior stabilization or in neutral rotation after a posterior stabilization procedure. Gentle passive range-of-motion exercises are started on the first day after surgery. Progressive rotator cuff and periscapular muscle strengthening exercises are started at 4 weeks. Full return to sports is allowed at 4 to 6 months, depending on the patient’s progress.

Infection, neurovascular injury, and anesthetic complications are rare serious complications of arthroscopic shoulder stabilization. Recurrent instability and loss of motion are more common complications.

It is difficult to determine the results of rotator interval capsule closure presented in the literature as the procedure is usually performed secondary to an anterior or posterior labral repair. Results of studies in which rotator interval closure was specifically described are presented in

Table 5-1

.

| Author | Type of Instability | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Ide et al[11] (2004) | Anterior | 50 of 55 (91%) good–excellent |

| Gartsman et al[8] (1999) | Anterior | 49 of 53 (92%) good–excellent |

| Noojin et al[16] (2000) | Anterior | 642 of 662 (97%) good–excellent |

| Kim et al[13] (2002) | Anterior (revisions) | 19 of 23 (83%) good–excellent |

| Bottoni et al[3] (2005) | Posterior | 29 of 31 (94%) good–excellent |

| Abrams[1] (2003) | Posterior | 42 of 49 (88%) good–excellent |

| Hewitt et al[10] (2003) | Multidirectional | 29 of 30 (90%) good–excellent |

1.

Abrams JS: Arthroscopic repair of posterior instability and reverse humeral glenohumeral ligament avulsion lesions.

Orthop Clin North Am 2003; 34:475-483.

2.

Almazan A, Ruiz M, Cruz F, et al: Simple arthroscopic technique for rotator interval closure.

Arthroscopy 2006; 22:230.

3.

Bottoni CR, Franks BR, Moore JH, et al: Operative stabilization of posterior shoulder instability.

Am J Sports Med 2005; 33:996-1002.

4.

Calvo A, Martinez AA, Domingo J, et al: Rotator interval closure after arthroscopic capsulolabral repair: a technical variation.

Arthroscopy 2005; 21:765.

5.

Cole BJ, Mazzocca AD, Meneghini RM: Indirect arthroscopic rotator interval repair.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:E28-E31.

6.

Cole BJ, Rodeo SA, O’Brien SJ, et al: The anatomy and histology of the rotator interval capsule of the shoulder.

Clin Orthop 2001; 390:129-137.

7.

Fitzpatrick MJ, Powell SE, Tibone JE, et al: The anatomy, pathology, and definitive treatment of rotator interval lesions: current concepts.

Arthroscopy 2003; 19:70-79.

8.

Gartsman GM, Taverna E, Hammerman SM: Arthroscopic rotator interval repair in glenohumeral instability: description of an operative technique.

Arthroscopy 1999; 15:330-332.

9.

Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, et al: The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74:53-66.

10.

Hewitt M, Getelman MH, Snyder SJ: Arthroscopic management of multidirectional instability: pancapsular plication.

Orthop Clin North Am 2003; 34:549-557.

11.

Ide J, Maeda S, Takagi K: Arthroscopic Bankart repair using suture anchors in athletes: patient selection and postoperative sports activity.

Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:1899-1905.

12.

Karas SG: Arthroscopic rotator interval repair and anterior portal closure: an alternative technique.

Arthroscopy 2002; 18:436-439.

13.

Kim SH, Ha KI, Kim YA: Arthroscopic revision Bankart repair: a prospective outcome study.

Arthroscopy 2002; 18:469-482.

14.

Lewicky YM, Lewicky RT: Simplified arthroscopic rotator interval capsule closure: an alternative technique.

Arthroscopy 2005; 21:1276.

15.

Neer CS, Foster CR: Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder. A preliminary report.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62:897-908.

16.

Noojin FK, Savoie FH, Field LD: Arthroscopic Bankart repair using long-term absorbable anchors and sutures.

Orthop Today 2000; 4:18-19.

17.

Treacy SH, Field LD, Savoie FH: Rotator interval capsule closure: an arthroscopic technique.

Arthroscopy 1997; 13:103-106.

18.

Van der Reis W, Wolf EM: Arthroscopic rotator cuff interval capsular closure.

Orthopedics 2001; 24:657-661.