CHAPTER 42 –

Cole & Sekiya: Surgical Techniques of the Shoulder, Elbow and Knee in Sports Medicine, 1st ed.

Copyright ©

2008 Saunders, An Imprint of Elsevier

CHAPTER 42 – Patient Positioning, Portal Placement, and Normal Arthroscopic Anatomy

Robin V. West, MD

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations adopted a protocol in 2004 to prevent wrong site surgery. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has been working on this same issue since 1997. Implementation varies from hospital to hospital, but in general, the surgeon or a “credentialed provider” on the surgical team places his or her initials on the operative site in indelible ink before administration of anesthesia. No other marking, such as an X, is recommended because it may be misinterpreted. The initials should be located in a region that remains visible after preparation and draping. Finally, during a “time-out” with the surgical team and operating room nurse, the site is confirmed again with the surgeon and the consent before an incision is made.

Several factors contribute to the decision of which type of anesthesia is most appropriate for a given patient. The decision to use local, regional, or general anesthesia depends on the planned procedure, the general health of the patient, and the preference of the patient, anesthesiologist, and surgeon.

Before knee arthroscopy is performed by use of local anesthetic with or without intravenous sedation, several factors are considered. The anesthesia team may need to convert to an alternative form of anesthesia if airway management becomes difficult. With this technique, patients generally do not tolerate use of a tourniquet. In some cases, patients may experience discomfort during manipulation of the leg and introduction of instruments into the knee. For these reasons, short procedures that do not require excess manipulation or bone work are best suited for local anesthesia. Suitable procedures include diagnostic arthroscopy, synovial biopsy, removal of loose body, and partial meniscectomy. Advantages of this technique are low morbidity, low cost, and ease of recovery. A combination of lidocaine and bupivacaine (Marcaine) is typically used to provide short-term and long-term pain relief. Epinephrine can be used in combination with the anesthetic to aid in hemostasis.

Regional anesthetic options include spinal, epidural, and femoral nerve anesthesia. For patients whose medical issues put them at increased risk with general anesthesia, regional anesthesia provides satisfactory anesthesia for most arthroscopic knee procedures. Tourniquet use is generally well tolerated with these techniques. Possible complications are spinal puncture and spinal headache.

Newer anesthetic agents continue to make general anesthesia safer with easier recovery. Complete muscle relaxation with general anesthesia allows better visualization of the joint. Tourniquet and bone work are tolerated by the patient. Patients may have throat irritation with the use of an endotracheal tube.

The patient is positioned supine on a standard operating table. If a tourniquet is used, a layer of padding is placed on the thigh before its application. In our institution, we rarely use a tourniquet, relying instead on the epinephrine in the local anesthetic and pump pressure to ensure adequate visualization during the procedure. We prefer not to use a tourniquet because of data that show an adverse effect on quadriceps function postoperatively when it is used.

On the basis of the surgeon’s preferences, one of two set-ups is used at our hospital. In the first, the patient lies supine on the table with the feet just short of the end of the table. The nonoperative leg is protected with foam padding. The operative leg is flexed to 90 degrees. A sandbag is taped to the table for the foot to rest on when the knee is flexed. A lateral post is attached to the table at the level of the distal thigh. The post helps stabilize the leg when a valgus force is applied to visualize the medial compartment. This method allows easy access to all aspects of the knee. However, an assistant is generally required to manipulate the leg during the case.

The other option entails placement of the thigh in a leg holder and flexion of the foot of the table. On the table, the patient’s operative knee must be just distal to the level of the break in the bed. The operative leg is placed into a leg holder. The opposite leg is placed into a well-leg holder and protected with foam under the knee. The operative leg is manipulated by placing it on the surgeon’s pelvis or thigh and applying a varus or valgus stress at the knee. If the leg holder is too tight, it can act as a venous tourniquet and cause bleeding during surgery. Whereas this method eliminates the need for an assistant, there is no support for the leg when it is in extension. Also, larger thighs may not fit well in the leg holder.

After the administration of anesthesia, a thorough examination is performed, including range of motion, patellar glide, instability tests, and documentation of an effusion. The contralateral knee is used as a comparison. Certain tests, such as a pivot shift, are better tolerated when the patient is completely relaxed. The findings of the examination are documented in the operative report. The surgeon also correlates the examination with the arthroscopic findings.

Arthroscopic equipment has continually improved in the years since its introduction. Better optical systems and the introduction of new instruments have broadened the number of ailments that can be treated arthroscopically. The scope of this chapter does not allow a comprehensive overview of all possible equipment.

Arthroscopes are described by their angle of inclination. A 0-degree scope looks straight-ahead; a 30-degree scope views at a 30-degree angle from the axis of the arthroscope. Rotation of the arthroscope increases the field of view compared with the straight-ahead view from a 0-degree scope. The 30-degree scope is used most commonly; a 70-degree scope is used for added visualization in tight spaces.

A surgeon uses the arthroscopic probe as an extension of his or her finger. The probe palpates various structures and provides tactile assessment of their condition. The probe can also be used as a measuring device for lesions in the joint. Most probe tips are calibrated to a known length, typically 3 mm. Besides assessing the menisci, articular cartilage, and ligaments, a probe can maneuver loose bodies into positions that facilitate their retrieval.

Arthroscopic biters are used to remove soft tissues, such as a torn meniscus or an anterior cruciate stump. These instruments come in a variety of shapes and sizes. The heads are angled in different directions to facilitate removal from areas that are difficult to reach. Use of an angled up-biter in the medial compartment helps the surgeon to reach the posterior meniscus by taking advantage of the convex nature of the medial tibial plateau.

Other instruments include graspers, scissors, motorized shavers and burs, and electrocautery devices. Various procedure-specific guides have been developed to assist in surgeries such as ligament reconstruction. The surgeon should take some time to become familiar with the instruments available from the hospital and various companies.

The inferolateral portal, also called the anterolateral portal, is traditionally used as the viewing portal through which the camera is inserted. The portal is made in the palpable soft spot just off the lateral border of the patellar tendon at the level of the inferior border of the patella. We prefer to keep this portal “high and tight” to avoid entry through the fat pad. The anterior portion of the lateral meniscus is also at risk with inferior placement of this portal. Excessive medial placement of the portal risks damage to the patellar tendon.

The inferomedial (or anteromedial) portal is used primarily as a working portal. The incision is made in the medial soft spot, just medial to the patellar tendon approximately 1 cm below the inferior border of the patella. To prevent injury to the medial meniscus when the portal is established, it can be made under direct visualization after localization with a spinal needle.

Historically, this portal was used for inflow or outflow of arthroscopy fluid. The portal is made 2 cm proximal to the superomedial border of the patella. The incision should be next to but not through the quadriceps tendon. During insertion, the trocar is angled into the suprapatellar pouch to avoid damage to the articular cartilage of the patella. If multiple passes are made through the soft tissues during insertion, fluid leak may occur and prevent adequate joint distention. To avoid trauma to the vastus medialis obliquus muscle, we do not routinely use this portal. Instead, we prefer to use a double-port cannula that allows inflow and outflow through the inferolateral portal. Studies have shown that use of the superomedial portal results in longer return of quadriceps strength and less total strength than with a standard two-portal technique.

Superolateral Portal (

Fig. 42-1

)

The superolateral portal allows visualization of the patellofemoral articulation, use for inflow or outflow, and removal of loose bodies from the suprapatellar pouch. This portal is made 2 cm proximal to the superolateral border of the patella. Entry through the interval between the vastus lateralis and the iliotibial band avoids injury to these structures. Use of the 70-degree arthroscope through the superolateral portal gives an excellent view of the patellofemoral articulation (

Fig. 42-1

).

Although it is rarely used, knowledge of this portal can facilitate repair of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus, removal of loose bodies, and synovectomy. The portal is made posterior to the lateral collateral ligament and anterior to the biceps tendon and the common peroneal nerve.

Posteromedial Portal (

Fig. 42-3

)

The posteromedial portal is established to view and to access the posterior portion of the medial compartment. This portal provides access to the tibial insertion of the posterior cruciate ligament and the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. The portal is marked preoperatively before the joint distends. The portal lies 2 cm above the joint line, 1 to 2 cm posterior to the medial femoral epicondyle. As establishment of this portal has a high risk of chondral or meniscal damage, we recommend use of a spinal needle under direct visualization to ensure accurate placement.

|

|

|

|

Figure 42-3 |

|

|

|

|

Figure 42-2 |

To establish this portal, a vertical slit is made in the central portion of the patellar tendon. This portal provides direct access to the intracondylar notch for either visualization or interference screw placement. Because of the risks of tendon irritation or rupture, this portal is rarely used.

Each surgeon needs to develop a systematic, reproducible method of examining the intraarticular structures of the knee. Multiple pictures are taken throughout the examination to document the findings of the procedure. Our systematic approach is described.

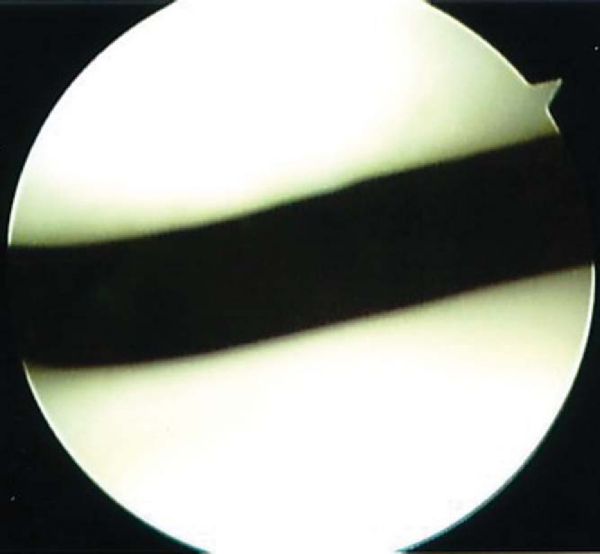

As the knee is extended, the blunt trocar is introduced into the suprapatellar pouch through the inferolateral portal. The pouch is inspected for loose bodies and adhesions from previous surgery. The camera is slowly pulled back until the undersurface of the patella comes into view. Cartilage damage or osteophyte formation is evaluated. The camera is rotated to view the trochlea. Cartilage damage is noted, and patellar tracking in the trochlear groove is assessed (

Fig. 42-4

). The superolateral portal provides the best view of the patellofemoral joint. The 70-degree arthroscope aids in visualization from this portal.

|

|

|

|

Figure 42-4 |

The lateral and medial gutters are visualized by passing the arthroscope across each condyle. The gutters are visualized all the way down to the joint line. On the lateral side, loose bodies may settle in the popliteal hiatus, so this area must be inspected.

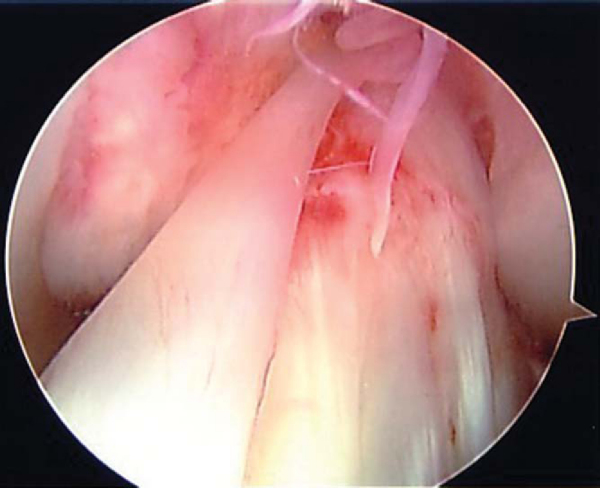

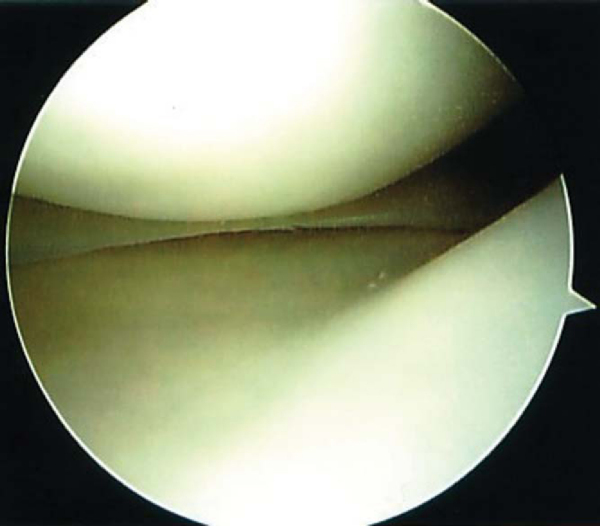

The medial compartment is entered by following the trochlea down into the intercondylar notch. A veil of tissue, the ligamentum mucosum, often covers the cruciate ligaments (

Fig. 42-5

). This tissue is either pulled aside with a probe or removed with a motorized shaver. The substance of the cruciates and their visible insertions are carefully inspected. Again, a probe is valuable in assessing the tension of the ligaments.

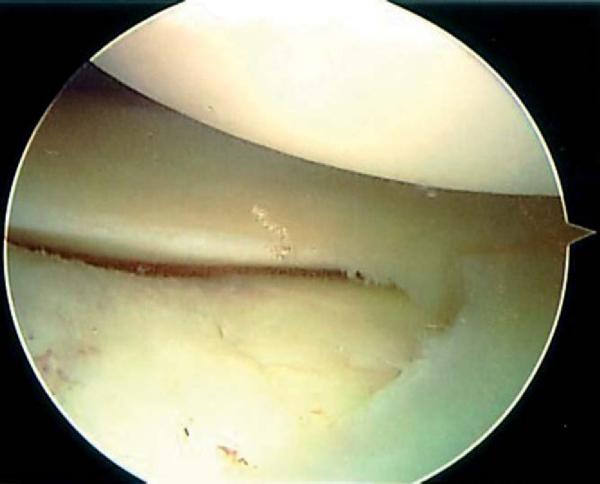

To enter the lateral compartment, a triangular space formed by the lateral border of the anterior cruciate ligament, the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus, and the lateral femoral condyle is identified. The arthroscope is directed into this space as the leg is placed into a figure-of-four position. An assistant can apply a varus stress by placing pressure on the medial aspect of the knee to open the joint further. The lateral meniscus is inspected and probed (

Fig. 42-6

). The popliteal tendon is seen passing through the popliteal hiatus. The leg is fully extended and flexed to assess the articular cartilage of the lateral compartment. If the scope is backed into the intercondylar notch with the knee in the figure-of-four position, the posterolateral bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament can be well visualized (

Fig. 42-7

).

|

|

|

|

Figure 42-7 |

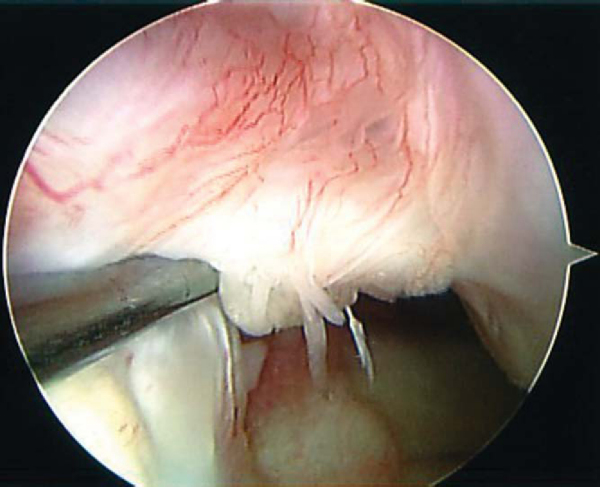

The medial compartment is then entered (

Fig. 42-8

). With varying degrees of flexion and valgus, the majority of the medial meniscus is clearly visualized. The camera is rotated to see the posterior horn more clearly. A probe is used to further assess the meniscus. The cartilage of the medial femoral condyle and the medial tibial plateau is examined for degeneration. The knee is flexed and extended to fully visualize the condyle.

In certain procedures, the posteromedial compartment needs to be assessed. Either the posteromedial portal or the Gilchrist view can be used to assess the posterior compartment. By the Gilchrist view, the posterior compartment can be viewed with the arthroscope in the anterolateral portal. The knee is flexed to 90 degrees and held in position against a sandbag placed preoperatively. A 70-degree arthroscope is carefully advanced between the medial femoral condyle and the posterior cruciate ligament. Rotation of the arthroscope downward brings the posterior horn of the meniscus into view. This view also locates loose bodies in the posterior compartment and shows the tibial insertion of the posterior cruciate ligament.

The portals can be closed with either a nonabsorbable or an absorbable monofilament suture. An ice machine is used to help provide postoperative hemostasis and to decrease inflammation. Exercises, including quadriceps sets, straight-leg raises, heel slides, and calf pumps, are started immediately after surgery. Crutches are used initially until the quadriceps function returns (typically a few days). Physical therapy is generally started the week after surgery. Narcotic pain medication is prescribed and selected on the basis of the procedure, the patient’s allergies, and the surgeon’s preference. An anti-inflammatory can be used for the first week to potentiate the narcotic medication. Preoperative intravenous antibiotics are routinely administered at our institution, and postoperative oral antibiotics are prescribed only for longer arthroscopic procedures (i.e., multiple ligament reconstruction).